Abstract

Across the globe there is growing skepticism about the usefulness of GDP as a measure of national well-being. Consequently, several alternative quality-of-life (QOL) measures were developed which either aim at healing the GDP, complementing it, or replacing it. This chapter portrays some of these new measures and puts them to a ‘happiness test’: compared to the GDP, are the new QOL measures better able to capture what makes people happy and satisfied with their lives? Using data for 34 OECD societies, we can show that from a happiness perspective, there is—surprisingly—little wrong with the GDP, and most alternative QOL measures do not outperform GDP. Yet, one measure actually does a better job: the OECD’s Better Life Index which is particularly effective when it comes to predicting subjective well-being in the richest OECD countries. In sum, the chapter demonstrates that a happiness perspective can add important insights along the way to facilitate the search for a new, widely accepted, internationally comparable measure of well-being.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

14.1 Introduction

There is currently a broad global movement away from considerations of mere economic success towards a new public policy goal involving a broader notion of quality of life. This movement has also spurred the rethinking of which statistics inform us best about a country’s situation and how its citizens are faring. For decades, the gold standard was a macroeconomic indicator: the GDP—gross domestic product, calculated per capita.Footnote 1 This is the most prominent yardstick that the media, politicians and the public consider when they try to assess how a country is performing. However, this measure was never meant to be a measure of the welfare of nations (as its creator Simon Kuznets already warned in the 1930s) and so there is growing skepticism about the GDP’s usefulness as a measure of national well-being. Slogans such as “beyond GDP” or “redefining progress” challenge the preoccupation with the GDP. Back in the 1960s, Robert Kennedy expressed his uneasiness as follows:

The Gross national product [GNP] does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry, or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debates or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything, in short, except what makes life worthwhile (Senator Robert Kennedy in a speech at the University of Kansas on March 18, 1968).

Since then, increasing numbers of social scientists, politicians, and ordinary citizens have begun to adopt this view. To meet the new demand, several alternative national performance measures have been developed, which either try to heal some of the conceptual problems of the GDP, complement the GDP with other indicators, or replace the GDP entirely. But do these new measures indeed make a better job of capturing “what makes life worthwhile”? This is our guiding question in this book chapter, which we address from the perspective of human happiness—the quality of life (QOL) as experienced by ordinary citizens (Veenhoven 2007). In other words: How well do the new measures of well-being perform compared with the GDP when seen through a “happiness lens”? Are those new measures of national well-being better able to capture what makes people happy and satisfied with their lives?

The chapter is organized as follows: we will start by briefly reviewing the rise and fall of the GDP as a welfare measure; then, some alternatives are sketched out; finally, we turn to data on subjective well-being from 34 OECD countries to ascertain whether the GDP indeed performs badly in predicting a population’s overall happiness and whether alternative measures perform better. The surprising answer is that from the happiness perspective, there is little wrong with the GDP, and most alternative QOL measures do not outperform the GDP. Yet, one measure does do a better job, and we close with the lessons happiness research provides for the construction of new—and better—welfare measures.

14.2 GDP/GNI: Their Rise and Fall

When the GDP was invented in the 1930s, it was not meant for metering a country’s overall well-being. Rather, it was intended for obtaining an idea of the direction in which the economy was moving, which was a pressing issue in the Great Depression of the 1930s. For that purpose, the GDP “compresses the immensity of a national economy into a single data point of surpassing density” (Gertner 2010, 1). More precisely, it adds up all the goods and services produced in an economy within a year. Thus, it has the advantage of being able to total entities with different units and to summarize them in one single monetary figure. Moreover, once the figure has been adjusted per capita and purchasing power parity, it can be easily compared across nations. Last but not least, the assumption behind using the GDP to assess well-being is that the higher the level of economic production, the better people are able to satisfy their needs. Arguably, in the post-war decades this made perfect sense, as people’s main concern was to improve their economic living situation. As a matter of fact, the material conditions in the industrialized world since 1945 have improved tremendously and it is right to assume that this has led to a significant increase in people’s quality of life.

However, as the Stiglitz Commission pointed out in the latest comprehensive survey of the weaknesses of the GDP (Stiglitz et al. 2009), the figure has a number of important downsides that should remind politicians to be cautious. First, the GDP does not take into account the distribution of income. The mean per capita does not contain any information on whether this reflects how the money is actually distributed among the citizens of a country. Second, we do not know from looking at the GDP whether the money is really spent on improving people’s living conditions. Third, the GDP does not account for sustainability and informal labor. In other words, current wealth may be produced at the expense of future generations, and a large part of production does not even feature in the GDP figure. In fact, a number of factors that are important for well-being (e.g., civic engagement, leisure, helping neighbors, informal childcare) are not captured because they take place outside the market. All of these caveats have led to numerous initiatives to find a better measure of the well-being of nations, which will be portrayed and then assessed from a happiness perspective in the remainder of this chapter.

14.3 The Search for a Better Measure: Three Main Strategies

Three key strategies have been employed to develop a better measure of well-being: healing the GDP, complementing the GDP, and replacing the GDP; we will briefly discuss each of these strategies. There is insufficient room here to undertake an extensive review of all the measures that have been suggested recently (Booysen 2002; Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress 2009; Hagerty et al. 2001; Kroll 2011). Instead, our main goal is to explain the logic behind the three major kinds of strategies.

14.3.1 Healing the GDP

The first group of initiatives tries to deal with the aforementioned downsides of the GDP by attempting to fix the indicator itself. In other words, the mode of calculation is adjusted in a way that hopes to overcome the existing weaknesses without departing too much from the basic logic of a measure that seeks to sum up goods and services in a comparable, monetary figure. The examples listed in the respective column in Fig. 14.1 function according to the same logic as the GDP in that they contain quantified information about different entities expressed as a monetary value. In contrast to the GDP, though, they are enriched with mainly social and environmental factors in order to address the blind spots of the GDP. The latter components are first monetized and then added to or subtracted from the original value of the GDP.

One key aim of this group of measures is to account for sustainability and the environmental damage associated with GDP growth. For example, the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (Cobb and Cobb 1994) and the Genuine Progress Indicator (Cobb et al. 1999) are both based on the consumption of private households. However, they also reflect additional social factors such as household labor and education with a rising value, while air pollution and environmental damage lower the score. As a consequence, the downsides of economic growth and modernization ought to be accounted for whilst retaining the benefits of the GDP, namely a single figure that captures different entities and is comparable across nations. In practice, however, the monetization of social and environmental factors contains a number of value judgments by the researcher and is therefore controversial. On balance, these kinds of well-being measure provide a step in the right direction as well as an important tool to engage with the downsides of the GDP for anyone keen to retain the advantages of the indicator.

14.3.2 Complementing the GDP

The second group of measures moves further away from the GDP as a yardstick than the previous approaches but does not abandon the sum of goods and services altogether. Instead, this group of measures seeks to assess national well-being by complementing the GDP with a number of key social indicators. In contrast to the aforementioned group, though, social and environmental factors are usually not forced into the logic of the GDP by means of monetization. Instead, the other indicators are standardized and subsequently merged with the GDP into a new index comprising a number of dimensions.

For example, the Human Development Index (see also the more detailed portrayal below) comprises the three dimensions health, education, and material living conditions, which are measured by life expectancy, years of schooling, and GNI, respectively. The three dimensions are standardized in order to produce a sub-index for each dimension that is then summarized into the total HDI score through a method of equal weights (one-third for each of the three dimensions).

While the method of complementing the GDP with further indicators is able to overcome the controversial monetization from which the measures that try to “heal GDP” suffer, the standardization of different units is also controversial. In particular, merging different units into a single standardized index is methodologically challenging and again requires value judgments by the researcher. Furthermore, it is unclear which precise dimensions ought to be included in such an index and how many are sufficient to deliver a good picture of the quality of life in a country. Nonetheless, this group currently provides the most prominent and widely accepted measures of national well-being in the sense of a safe middle ground between the two other approaches outlined here.

14.3.3 Replacing the GDP

The most radical departure from the GDP is embodied by the third group of measures, which seeks alternative indicators of well-being without accounting for the sum of goods and services produced in an economy. The logic behind this approach is that the GDP has always been and remains a means to an end rather than the end itself. Thus, according to this approach it would be more appropriate to examine the key indicators that really make life worth living rather than looking at economic production, which merely serves to improve those other indicators.

Famous examples include the Happy Planet Index (nef 2009) calculated by the New Economics Foundation (nef). The index comprises life expectancy, life satisfaction, and the ecological footprint and is therefore able to demonstrate how many resources countries need in order to produce a certain level of health and subjective well-being (SWB). As a result, Latin American countries, which have high levels of SWB despite smaller ecological footprints, top the list (with Costa Rica in the lead). In the end, industrialized Western nations are dragged down compared with their traditional GDP rankings as they require far more resources to produce comparable levels of health and life satisfaction.

Another example is the Happy-Life-Expectancy (Veenhoven 1996, 2005), which merges life expectancy and people’s subjective satisfaction with life into one single index. Yet another approach is to eliminate objective indicators entirely and to rely exclusively on people’s own evaluation of their quality of life. This approach, in reference to the GDP also known as Gross National Happiness (Veenhoven 2007), argues that citizens are best equipped to evaluate their lives, and that relevant life circumstances translate into more or less positive evaluations, after being filtered by personal life goals, aspirations, and social comparisons.

Replacing the GDP altogether is quite a drastic strategy for assessing national well-being, as not only is economic growth a prerequisite for many of the social goods that make life enjoyable but the metric of GDP is also highly correlated with such other factors (Kassenböhmer and Schmidt 2011). Thus, by arguing that the GDP is only a means to an end, these measures are in danger of making a conceptual assumption that is noble in theory but can be challenged in practice on the basis of actual causal mechanisms and empirical data.

14.4 Six Alternative Measures Portrayed

In this section we briefly portray six widely used QOL measures, which we later put in a horse race against income measures (GNI). Since this horse race is run for 34 OECD countries, we selected measures that are available for a broad number of countries, which excludes “strategy 1 measures” (healing the GDP). Since we will use information on citizens’ subjective well-being to judge how well the GNI and other measures “measure what makes life worthwhile” (Kennedy), we further exclude from both the “strategy 2 measures” and the “strategy 3 measures” those that rely in part or entirely on information on subjective well-being. The exception is the “OECD Better Life Index,” which we turned into a measure without SWB by excluding the respective dimension. This leaves us with six measures, four of them complementing the GDP and two replacing the GDP (see Fig. 14.1—the measures we portray are printed in bold).

14.4.1 Human Development Index

A long-standing and perhaps the most prominent alternative measure is the Human Development Index (HDI), which is based on Sen’s capabilities approach (Sen 1993). The HDI integrates health, education, and economic affluence into a human development framework, and it is this pluralistic conception that Sen himself regards as groundbreaking (Sen 2000). More precisely, five indicators are merged in a two-step process: first into three domain indices and then into an overall HDI score, which can take values between 0 and 1. Although some technicalities of the index construction have been repeatedly criticized (Lind 2004, 2010), the HDI has received a great deal of attention and is currently the main rival of the GDP. Almost all the OECD countries are ranked in the category “very high human development,” with Norway, Australia, and New Zealand leading the HDI league table (UNDP 2010). Turkey (lowest), Mexico, and Chile are the OECD laggards, but still rank as having “high human development.”

14.4.2 Inequality-Adjusted Human Development Index

In the 2010 Human Development Report (UNDP 2010), for the first time an inequality-adjusted HDI is presented: the I-HDI. This innovation reflects the criticism that the statistical means from which the HDI scores are calculated do not contain any information on how health, income, and education are distributed across the population. How citizens fare crucially depends on the distribution of human development within a country, though. To heal this conceptual problem, each of the three human development components account for distribution issues. Consequently, the overall index is inequality-adjusted as inequalities are integrated in such a way that the percentage loss in human development is calculated. In other words, the I-HDI tells us how much the human development in a country falls short of the potential human development under the condition of complete equality. Logically, the I-HDI values are always lower than the HDI values. Among the OECD countries, the most developed are Norway, Australia, and SwedenFootnote 2; the laggards are Turkey (lowest), Chile, and Mexico.

14.4.3 OECD Better Life Index

The recently launched Better Life Initiative (OECD 2011) features a compendium of well-being indicators, as well as a new composite index. The Better Life framework distinguishes between two main concepts: material living conditions and quality of life. Material living conditions are metered in three life domains: income and wealth; jobs and earning; and housing. Quality of life is measured in eight life domains: health status; work and life balance; education and skills; civic engagement and governance; social connections; environmental quality; personal security; and subjective well-being. With these 11 life domains, the OECD aims to examine the most relevant features that shape people’s lives. In total, twenty-one social indicators are utilized for quantifying these life domains. The OECD compendium reports country rankings across all 21 indicators, but does not deliver an authoritative index. The idea behind this strategy is to show the complexity of well-being, rather than brushing over this complexity by condensing everything into one single number. However, the OECD project website provides an easy tool for computing such an index, whereby the user is invited to apply his or her preferred weighting to the 11 life domains. In this chapter we will use an index in which every life domain carries equal weight, bar subjective well-being, which is excluded. The simple reason is that in the next section we will explain the international variation in subjective well-being by national performance measures, hence SWB cannot appear on both sides of the equation. In this equal-weight index (ex. SWB), the countries scoring highest on the OECD index are Australia, Canada, and Sweden/New Zealand, which are on a par; the countries scoring lowest are Turkey (lowest), Mexico, and Chile. No matter how the domains are weighted, the theoretical range of the Better Life Index is between 0 and 10, and the higher the index value, the better is life.

14.4.4 Index of Social Progress

The Index of Social Progress (Estes 1998, 2010) is probably one of the most encompassing national performance measures. Its main conceptual focus is social development, more precisely adequacy of social provision. This concept refers to “the changing capacity of governments to provide for the basic social, material, and other needs of the people living within their borders, e.g., for food, clothing, shelter, and access to at least basic health, education, and social services” (Estes 1998). In total 41 indicators are used to capture nine dimensions: education, health status, women’s status, defense effort (-), economy, demography, environment, social chaos (-), and cultural diversity; (-) denotes domains that are, conceptually, negatively linked to social progress. Separate factor analyses are run over the nine domains to create a subindex score for each domain. These subindices are then further factor analyzed in order to arrive at the WISP, the Weighted Index of Social Progress (cf. Estes 2010, p. 367 and Table 2 for a more detailed description of this procedure). The WISP is calculated worldwide and allows comparisons over time. Among the OECD countries, Sweden, Denmark, and Norway are the “social leaders,” whereas Turkey (lowest), Mexico and South Korea are the “social laggards.”

14.4.5 Well-Being Index

The Well-Being Index (McGillivray 2005) is a close cousin of the Human Development Index. In fact, it uses exactly the same indicators, except per capita income, which is excluded altogether. Hence, the WBI merges information from two domains, health and education, only. The second difference is how the data are merged. Whereas the HDI uses a predefined weighting scheme, the WBI uses factor analysis (principal component analysis): it is the strongest factor that emerges out of life expectancy, adult literacy, and gross enrollment. The OECD countries with the highest well-being are Australia, Belgium, and the United Kingdom; those with the lowest well-being are Turkey (lowest), Mexico, and Hungary. For our purpose, the WBI is a valuable indicator exactly because it omits the economic dimension entirely.

14.4.6 Social Development Index

The Social Development Index (SDI) was originally constructed in 1989 and updated in 2008 with newer cross-national data (Ray 2008). The composite index follows on from the Physical Quality of Life Index (PQLI) but claims to be a better tool for international comparisons as it is a broader, multi-dimensional approach. The SDI indeed includes 10 development indicators (rather than 3 as in the PQLI) to represent social development across 102 countries. The components are life expectancy, adult literacy rate, gross enrollment ratio, infant survival rate, supply of calories, proteins, and fat per day, respectively, telephone lines per 1,000 people, physicians per 100,000 people, as well as electricity consumption. The ranking is topped by Norway, Sweden, and the US, while Mexico (lowest), Chile, and Turkey are at the bottom of the SDI.

14.5 Do the New Measures Outperform the GDP? Some Empirical Insights from the Perspective of Human Happiness

As we have seen, the GDP has mainly attracted criticism as a measure of societal well-being because of its narrow focus on economic production. In fact, all theoretical conceptions of individual quality of life emphasize the multi-dimensionality of what matters to people (for a review, see Philips 2006). Erik Allardt, for instance, defined the three pillars of personal quality of life as having, loving, and being (Allardt 1993). In a similar fashion, Maslow (1943) claimed earlier that humans are motivated by five basic needs, which are hierarchically ordered: physiological needs; safety needs; social needs; esteem needs; and self-actualization needs. Doyal and Gough (1991) produced a more extensive list of 11 intermediate needs, covering, among other things, housing, health care, relations with others, economic security, and education.

Bearing these conceptions in mind, it is more than plausible that broader QOL measures should capture what matters to people better than the GDP. This expectation can also be derived from individual-level happiness research, which has repeatedly demonstrated that a number of things make individuals happy—among them income and a comfortable living standard, but many other things as well (Layard 2005). Layard lists the “big seven” individual-level factors affecting happiness as family relationships, financial situation, work, community and friends, health, personal freedom, and personal values. Likewise, when Europeans are asked what matters for their personal quality of life, almost everywhere people pick the triad of income, family, and health (Delhey 2004).

The following empirical exercise investigates whether, as measures of national well-being, the new QOL measures outperform the GDP. Our yardstick is average self-reported happiness with life as a whole (Veenhoven 1984). Arguably, the things that really matter to people (remember Kennedy’s verdict) should show up on their personal balance sheet of life—their overall happiness. If the new QOL measures are better able to capture these salient concerns than the GDP, the former should be better at predicting average happiness than the latter.

14.5.1 Measuring Happiness

For the concept of happiness as defined above, three different concrete measures are common in cross-national research (Veenhoven 2007):

Cantrils’s ladder of life, also called life contentment (example from Gallup World Poll):

Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you stand at this time?

Life satisfaction (example from the World Values Survey):

All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days? Please use this card to help with your answer [1 dissatisfied (…) 10 satisfied].

Life happiness (example from the World Values Survey):

Taking all together, how happy would you say you are: very happy, quite happy, not very happy, not at all happy?

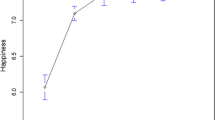

We collected data on these three measures for 34 OECD countries. The contentment scores came from the Gallup World Poll 2010, reported by the OECD (2011). The life satisfaction and happiness scores were computed from either the World Values Surveys or the European Values Study 2008; for each country, we took the latest year available. At the country level, all three measures are highly correlated: contentment–life satisfaction at 0.77; contentment–happiness at 0.69; and life satisfaction–happiness at 0.81. We merged all three into one single score of SWB.Footnote 3 The resulting relative scores meaningfully differentiate the degree of life enjoyment; the higher the score, the higher a population’s overall subjective well-being. As Fig. 14.2 shows, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Norway are the countries where citizens—on average—enjoy life most, whereas in Hungary, Estonia, and Turkey, life enjoyment is the lowest.

14.5.2 Some Simple Correlations

How well does the GDP predict the national SWB? As Fig. 14.3 shows, the correlation between GNI per capita (in purchasing power parities, to adjust for different price levels) and average SWB is very strong (0.58) and highly significant. By and large, people enjoy life more in richer countries. There is also no sign of a leveling of this association among the richest nations, as it is often claimed (Inglehart and Klingemann 2000). If one uses a logged scale of GNI per capita, as advocated by many economists, the regression line is even slightly concave, again suggesting that there is no decreasing marginal utility of national income.

Do the new QOL measures perform better than the GNI? The surprising answer is no, not across the board (see Table 14.1). Only one single measure outperforms the GNI, namely the Better Life Index (exclusive of subjective well-being). The correlation coefficient between Better Life and SWB is a highly significant 0.67. In contrast, most other measures, from HDI over WBI and I-HDI to SDI, perform slightly worse than the GDP, with coefficients between 0.51 and 0.47. Finally, the Index of Social Progress (WISP) performs considerably worse than the GDP. The WISP’s mild correlation with the average SWB does not reach the usual threshold of statistical significance of p < 0.05. This is somewhat surprising, given that the WISP is a convergence of so many social indicators, yet it suggests that the normative assumptions underlying the WISP of what social progress entails are not fully shared by ordinary citizens. Obviously, the WISP includes indicators that are irrelevant to human happiness—or if relevant, it treats them in a way that does not conform to the OECD citizens’ happiness calculus.Footnote 4 Figure 14.4 displays the scatterplots for the best- and the worst-performing QOL measures, the Better Life Index and the Index of Social Progress.

These findings are confirmed if we look at the three component parts of SWB separately (Table 14.1). Across the three components, the Better Life Index is most closely associated with people’s enjoyment of life, followed by the GNI. However, Better Life typically wins by a narrow margin only. Equally consistently, the WISP has the weakest association with all three SWB components, and reaches the typical threshold of statistical significance for just one component, life satisfaction. Another important message emerges from Table 14.1: of the three SWB components, the average life contentment is most closely associated with the objective well-being indexes, regardless of which one we consider. Across the board, the correlation coefficients are higher for life contentment than for life satisfaction and happiness. This again proves that the three concrete measures of life enjoyment are not fully interchangeable, and that the results produced with one measure do not necessarily hold for the other measures as well (Bjornskov 2010).

14.5.3 Explaining National SWB

It is well known that overall life enjoyment cannot fully be explained by societal conditions, and this is suggested by our correlations as well. At least to some extent, national or world-regional peculiarities influence SWB levels over and above societal conditions, which we can capture in accounts of objective living conditions. It is widely known, for example, that Latin Americans are “happiness overachievers”—they are more upbeat than their societal conditions suggest (Diener et al. 2000). In contrast, Eastern Europeans are known to be “happiness underachievers”—they are typically less satisfied than their societal conditions suggest, remaining in the aftermath of the system collapse from 1989 to 1992 (Deaton 2008; Inglehart et al. 2008). To some extent, these peculiarities also surface in the SWB scores presented here (Figs. 14.2, 14.3): whereas in the scattergrams Chile and in particular Mexico are positioned above the fit lines (SWB overachievers), Estonia and Hungary are positioned below the fit lines (SWB underachievers). However, this latter pattern is much less clear for the other post-communist OECD countries, the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovenia, and Slovakia. The next step of the analysis accounts for these world-regional peculiarities. With linear regressions, the average SWB is explained by national well-being (the various measures are used in turn), while controlling for “Latin America” and “Eastern Europe.” For that purpose, two dummy variables distinguish between Latin American and other countries, and between Eastern European and other countries, respectively. To make the size of the coefficients comparable across the various QOL measures, the latter are standardized into Z-scores, so that they no longer use a different metric. The regression results are shown in Table 14.2.

When the two region dummies are included, the GNI exerts a strong and statistically highly significant influence on the average SWB: people do rate their lives better in richer countries, independently of which income scale is used, linear or logarithmic. Together with the two region dummies—of which only “Latin America” is significant—the GNI explains roughly half of the international variance in SWB. Again, only the Better Life Index turns out to have an advantage over income: its regression coefficient is higher (although still within the confidence interval of the income measures’ coefficients), and together with the region dummies, the Better Life Index can account for roughly three-quarters of the variance in SWB. In contrast, most other QOL measures perform more or less similarly to income, and the WISP performs worse.

A useful extension of the analysis is to look at the group of the richest OECD nations separately, since quality of life, rather than income alone, is often seen as the key concern in affluent societies. We use two different thresholds for defining “rich” societies, one derived from the World System Theory (organic core countries, cf. Babones 2005), the other being a GDP per capita threshold of $25,000. This leaves us with 19 “core countries” and 20 “rich countries.” For these two groups of countries, Better Life shows by far the strongest association with SWB, even more strongly than for the entire group of 34 countries (see Table 14.3). In contrast, most other well-being measures, including the GDP, are less strongly and less significantly associated than for the full sample. For the core countries in particular, the associations are typically weaker. The exception is the inequality-adjusted HDI, which correlates more strongly with SWB among core/rich countries than among all 34 OECD nations .

14.6 Conclusion: The Bumpy Road Towards a New Gold Standard

This chapter departed from Kennedy’s famous dictum that the GNP “measures everything (…) except that which makes life worthwhile (…).” Following this line of thought, a movement that seeks to replace the GDP with a better, more encompassing summary indicator of well-being has gained momentum (see Kroll 2011 for an overview). Implicitly or explicitly, these new measures claim to capture better what makes life worthwhile. However, most new measures fail to deliver what they promise, if we use the average subjective well-being as expressed in representative surveys as the yardstick. Only the OECD’s Better Life Index (to repeat: exclusive of SWB, of course) has an advantage over the GNI in this respect. In contrast, all the other QOL measures employed do not perform better in predicting subjective well-being than the GNI, and one measure—the Index of Social Progress—performs worse.

Several lessons can be drawn. One straightforward lesson is that economic activities and the affluence they create actually do make life worthwhile for a huge majority of people–even among the OECD countries, of which many are affluent. This suggests that what Samuelson and Nordhaus observed 60 years ago is still valid today: “People do not live by bread alone. Nor does society live by GNP alone. But on our way to that utopian state of affluence where concern about material well-being will disappear, we do need a summary measure of aggregate economic performance” (quoted from Sills and Merton 1991). Yet the question is whether it is affluence as such that nurtures life enjoyment in contemporary OECD societies, or the many good things and activities for which money can be used. In that sense, money can help satisfy a number of human needs, rather than the need to consume alone. Globally, national income correlates strongly with social progress in terms of health and education, and it also correlates with desired institutional qualities such as democracy and rule of law (Delhey and Newton 2005; Inglehart and Welzel 2005). In a similar fashion, data analyses for Germany have shown that much of the variation in alternative well-being indicators, as suggested by the Stiglitz Commission, can be captured well by economic indicators alone, especially the GDP and the unemployment rate (Kassenböhmer and Schmidt 2011). In short, modernization is a tight-knit syndrome, and prosperity is an integral part of it, as argued by the human empowerment theory (Inglehart and Welzel 2005).

Does this mean that the new performance measures are redundant? This conclusion would be premature–provided that the new measures are not too closely modeled after the concept of development/modernization. Although being broader than the GNI, the HDI, I-HDI, WBI, and SDI obviously do not capture more of the things that make life worthwhile, since they do not make a difference to human happiness. On the other hand, the example of the encompassing Index of Social Progress demonstrates that extreme broadness is not the trick either. Either the WISP’s dashboard of indicators is flawed (in the sense that the researcher’s idea of what constitutes progress deviates from the laymen’s idea), or the mathematical index construction (e.g., too much weight is given to things that ordinary people do not value much, from a happiness perspective).

The measure that indeed does make a better job than the GNI of predicting national subjective well-being is the Better Life Index. This holds for all the OECD countries, and in particular for the subset of the richest/core countries. Obviously, its life domains and selection of indicators capture the life facets that OECD citizens truly value, over and above the achieved level of economic advancement. More research is needed here to find out exactly what these extra components are that give the Better Life Index added value. Given the fact that previous research has revealed that social capital (especially when compared with the GDP) matters more for the SWB of rich countries than for that of poorer ones (Kroll 2008), our informed guess is that issues of social capital, social cohesion, and greater equality make the difference here. The fact that the inequality-adjusted HDI, too, works very well for the rich/core countries points in a similar direction.

One idea for improving the Better Life Index further is to use measures of subjective well-being to calibrate the index. In our analysis, each of the ten Better Life domains carries equal weight, in the absence of a convincing theoretical argument for why the domains should be treated unevenly. Yet instead of assigning equal weights, the strength of the association between the various life domains and the average SWB could be used for assigning differential weights, so that the domains that matter greatly to people’s life enjoyment enter the index with a stronger weight than those domains that matter less (see The Economist’s 2005, Quality-of-Life Index for a similar approach). Apart from the weighting issue, it might also turn out that there are better strategies than merging all the information into one single composite index. An alternative would be to factor analyze the Better Life data matrix in order to establish how many separable dimensions of national well-being are captured in the data. Yet another alternative would be to select from the dashboard of Better Life domains those that together explain the international variation in life enjoyment best, following the idea of “income + x.”

To summarize our argument, for an economic indicator never intended to assess national well-being, the GDP is surprisingly successful in predicting a population’s subjective well-being. At the same time, the theoretical claim of the social indicators movement about the multi-dimensionality of human concerns is a valid criticism, and conceptually it should be possible to come up with performance measures that embrace this multi-dimensionality better than an economic performance measure alone. Even if we lived in a world where the GDP performs exactly identically to a composite index of quality of life, on theoretical grounds one could still argue that the latter is more appropriate than the former for formulating evidence-based policy. Although a new gold standard in measuring national well-being has not been found yet, the Better Life Index demonstrates that progress towards this goal is possible. This chapter has demonstrated that a happiness perspective can add important insights along the way to facilitate the search for such a new, widely accepted, internationally comparable measure .

Notes

- 1.

The gross domestic product (GDP), gross national product (GNP) and gross national income (GNI) are all measures of national economic output that are used interchangeably in this chapter. The GDP is the total value of the final goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a year. The GNP is the total value of all the final goods and services produced by a country’s factors of production and sold on the market in a year. Last but not least, the GNI comprises the total value of the goods and services produced within a country, together with its income received from other countries (notably interest and dividends), less similar payments made to other countries (Black 2003).

- 2.

We have no I-HDI data for New Zealand, which ranks third in the HDI.

- 3.

The measures were first transformed into Z-scores and then added up. Each SWB component was assigned equal weight.

- 4.

For example, low fertility enters the WISP with a negative sign—as social regress. Yet for many people, having few children indicates control over one’s life, which is valued by many humans.

References

Allardt E (1993) Having, loving, being: an alternative to the Swedish model of welfare research. In: Nussbaum M, Sen A (eds) The quality of life. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp 88–94

Babones S (2005) The country-level income structure of the world economy. J World Syst Res, XI, pp 29–55

Bjornskov C (2010) How comparable are the Gallup World Poll life satisfaction data? J Happiness Stud 11:41–60

Black J (2003) A dictionary of economics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Booysen F (2002) An overview and evaluation of composite indices of development. Soc Indic Res 59:115–151

Cobb CW, Cobb JB (1994) The green national product: a proposed index of sustainable economic welfare. University of America, Lanham

Cobb C, Goodman GS, Wackernagel V (1999) Why bigger isn’t better: the genuine progress indicator. Redefining Progress, San Francisco

Commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress (2009) Survey on existing approaches to measuring socio-economic progress. Available at: www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr/documents. Accessed on 30 Apr 2012

Deaton A (2008) Income, health and wellbeing around the world: evidence from the Gallup World Poll. J Econ Perspect 22:53–72

Delhey J (2004) Life satisfaction in an enlarged Europe. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Dublin

Delhey J, Newton K (2005) Predicting cross-national levels of social trust: global pattern or Nordic exceptionalism? Eur Sociol Rev 21:311–327

Diener E, Scollon CKN, Oishi S, Dzokoto V, Suh EM (2000) Positivity and the construction of life satisfaction judgements: global happiness is not the sum of its parts. J Happiness Stud 1:159–176

Doyal L, Gough I (1991) A theory of human need. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Estes RJ (1998) Trends in world social development, 1970–1995. Development challenges for a new century. J Developing Soc 14:11–39

Estes RJ (2010) The world social situation: development challenges at the outset of a new century. Soc Indic Res 98:363–402

Gertner J (2010) The rise and fall of G.D.P. Times Magazine, New York

Hagerty MR, Cummins RA, Ferriss AL, Land K, Michalos A, Peterson M, Sharpe A, Sirgy J, Vogel J (2001) Quality of life indexes for national policy: review and agenda for research. Soc Indic Res 55:1–96

Inglehart R, Foa R, Peterson C, Welzel C (2008) Development, freedom, and rising happiness. A global perspective, 1981–2007. Perspect Psychol Sci 3:264–285

Inglehart R, Klingemann HD (2000) Genes, culture, democracy, and happiness. In: Diener E, Suh EM (eds) Subjective well-being across cultures. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 165–183

Inglehart R, Welzel C (2005) Modernization, cultural change and democracy. The human development sequence. Cambridge University Press, New York

Kassenböhmer SC, Schmidt CM (2011) Beyond GDP and back: what is the value-added by additional components of welfare measurement? DIW: SOEP papers 351

Kroll C (2008) Social capital and the happiness of nations. The importance of trust and networks for life satisfaction in a cross-national perspective. Peter Lang Publishing, Frankfurt a.M

Kroll C (2011) Measuring progress and well-being: achievements and challenges of a new global movement. Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Berlin

Layard R (2005) Happiness. Lessons from a new science. Penguin Books, London

Lind N (2004) Values reflected in the human development index. Soc Indic Res 66:283–293

Lind N (2010) A calibrated index of human development. Soc Indic Res 98:301–319

Maslow AH (1943) A theory of human needs. Psychol Rev 50:296–370

McGillivray M (2005) Measuring non-economic well-being achievement. Rev Income Wealth 51:337–364

nef (2009) The happy planet index 2.0. The New Economics Foundation, London

OECD (2011) OECD better life initiative. Compendium of OECD well-being indicators. Organization of Economic Co-Operation and Development, France

Philips D (2006) Quality of life. Concept, policy and practice. Routledge, London

Ray AK (2008) Measurement of social development: an international comparison. Soc Indic Res 86:1–46

Sen A (1993) Capability and well-being. In: Nussbaum M, Sen A (eds) The quality of life. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp 31–53

Sen A (2000) A decade of human development. J Hum Dev 1:17–23

Sills DL, Merton RK (1991) Social science quotations. Who said what, when, and where. McMillan Publishing Company, New York

Stiglitz JE, Sen A, Fitoussi J-P (2009) Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Available at: http://www.stiglitzsen-fitoussi.fr/en/index.htm. Accessed on 30 Apr 2012

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s quality-of-life index (2005) In: The Economist. The World in 2005, pp 1–4

UNDP (2010) Human development report 2010: the real wealth of nations: pathways to human development. United Nations Development Program, New York

Veenhoven R (1984) Conditions of happiness. Springer, Doordrecht

Veenhoven R (1996) Happy life expectancy: a comprehensive measure of quality of life in nations. Soc Indic Res 39:1–58

Veenhoven R (2005) Apparent quality-of-life in nations: how long and happy people live. Soc Indic Res 71:61–86

Veenhoven R (2007) Measures of gross national happiness. In: OECD (ed) Measuring and fostering the progress of societies. OECD Publishing, Paris, pp 232–253

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Delhey, J., Kroll, C. (2013). A “Happiness Test” for the New Measures of National Well-Being: How Much Better than GDP are They?. In: Brockmann, H., Delhey, J. (eds) Human Happiness and the Pursuit of Maximization. Happiness Studies Book Series. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6609-9_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6609-9_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-6608-2

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-6609-9

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)