Abstract

In this chapter, I argue that on a natural understanding of both views, indeterminism and branching time are incompatible, contrary to what recent literature on the open future suggests. In the first section, I introduce two notions of truth-determination that importantly differ from the notion of truth-making. In the second section, I use these notions to devise a definition of determinism that captures the central idea that, given the past and present, the future cannot but be a certain way. Indeterminism is then defined in opposition to determinism in the third section. In the fourth section, I argue that the tree-like representation of future possibilities is not suggestive of branching time and that indeterminism is perfectly consistent with assumption of a Thin Red Line, that is, a unique way things will turn out to be, a claim shown to be unthreatened by considerations concerning human freedom. In the fifth section, I argue that taking branching time seriously implies commitment to determinism. In the sixth section, I consider a recent attempt to capture the open future and show that it is naturally seen to draw on a conception of the determinately true as what is determined to be true in the second of the senses introduced in the first section. In the seventh section, I argue that the authors’ suggestion that determinism is nonetheless consistent with admission of a multitude of future possibilities is at best unmotivated and at worst misguided. Section eight summarises the results.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Two Notions of Truth-Determination

It is a widespread assumption in discussions about the open future that indeterminism and branching time are natural companions. Here I shall argue that, first appearances notwithstanding, this assumption is mistaken and that, on the contrary, branching time implies determinism. This thesis will be based on conceptions of determinism, indeterminism and branching time that I consider to be the most natural. However natural they may be, they are not uncontroversial. For this reason, I shall use labels in small caps for the particular conceptions of determinism, indeterminism and branching time to which my thesis is meant to apply, while reserving labels in normal font for the generic notions.

If branching time implies determinism, indeterminism had better be compatible with linear time. Indeed it is, or so I shall argue. Indeterminism can be combined with assumption of a Thin Red Line, that is, of a unique way things will turn out to be, without one of the principal motives for accepting it thereby being undermined: human freedom remains untouched by admission of such a Thin Red Line.

The conceptions of determinism and indeterminism to be proposed essentially involve two notions of truth-determination, one a special case of the other, which importantly differ from the notion of truth-making (cf. Correia and Rosenkranz 2011: 28–29). Before I can begin arguing my case, these notions must be made explicit. Although their explicit definitions are rather involved, the notions themselves are in the end fairly easy to grasp, as testified by the informal glosses they allow.

To begin with, and mostly for ease of exposition, let us make the following assumptions and adopt the following conventions. Let the variable ‘t’, and primed versions thereof, range over times, and let the variable ‘f’ range over facts, where we will assume facts to be tensed and will be very liberal as to what tensed facts there are, admitting, in particular, the existence of negative facts. It will be assumed throughout that the debate between determinists and indeterminists does not turn on these issues.Footnote 1 Let us choose a day as our unit for measuring temporal distances. Finally, let us use ‘n days from the present, q’ for ‘Presently, q’ in case n = 0, for ‘-n days ago, q’ in case n < 0, and for ‘n days hence, q’ in case n > 0. Correspondingly, ‘t is n days from t′ ’ will be used for ‘t = t′ ’ in case n = 0, for ‘t is -n days earlier than t′ ’ in case n < 0, and for ‘t is n days later than t′ ’ in case n > 0. Unless indicated otherwise, all truth-functionally simple statements will be assumed to be of the form ‘n days from the present, q’.

Now say that a statement p is determined1 to be true at t iffdf there is a collection of statements Σ and a function δ from the members of Σ to numbers suitable for measuring temporal distances such that:

-

(i)

∀q∈Σ(∃t′ (t′ is δ(q) days from t & at t′, ∃f(q is made true by f)))

-

(ii)

□∀t′ [(∀q∈Σ(∃t″ (t″ is δ(q) days from t′ & q is true at t″))) → p is true at t′].

Crudely put, for a statement to be determined1 to be true at a given time is for its truth at that time to be necessitated by truth-makers that are, at that time, past, present or future (is for that statement to be true at that time in virtue of what then has been, is or will be the case).

By contrast, say that a statement p is determined2 to be true at t iffdf there is a collection of statements Σ and a function δ from the members of Σ to numbers suitable for measuring temporal distances such that:

-

(i)

∀q∈Σ(∃t′ (t′ is δ(q) days from t & at t′, ∃f(q is made true by f)))

-

(ii)

□∀t′ [(∀q∈Σ(∃t″ (t″ is δ(q) days from t′ & q is true at t″))) → p is true at t′]

-

(iii)

∀q∈Σ(δ(q) ≤ 0).

Less formally, for a statement to be determined2 to be true at a given time is for its truth at that time already to be necessitated by truth-makers that are, at that time, past or present but not future (is for that statement to be true at that time already in virtue of what then has been or is the case).

Note that while ‘p is determined2 to be true at t’ straightforwardly entails ‘p is determined1 to be true at t’, the converse does not hold. While truth-determination2 is just a special case of truth-determination1, the contention that whatever is determined1 to be true is determined2 to be true requires substantive argument. Note also that while to say that p is made true at t is to say that there is, at t, some fact that makes it true, to say that p is determined1 to be true at t is not yet to say that there is, at t or any earlier time, some fact that does the determining1. Thus, it is perfectly consistent to say that a future-tensed statement such as ‘n days from the present, p’, with n > 0, is determined1 to be presently true in virtue of there being n days from the present, a fact that then makes ‘Presently, p’ true but does not exist -n days from then (cf. Dummett 2004: 81; Correia and Rosenkranz 2011: 28–29).

The contrast between truth-determination1 and truth-determination2 may successfully be exploited in order to account for the problem of foreknowledge (cf. Prior 1967: 113–21). Very plausibly, ‘Yesterday, God knew that 50 days thence a sea battle would take place’ will be determined2 to be presently true only if ‘50 days hence, a sea battle will take place’ was determined2 to be true yesterday, and hence only if ‘49 days hence, a sea battle will take place’ is determined2 to be true today. But then, provided that what is temporally necessary, or predetermined, is determined2 to be the case, if the latter statement is not determined2 to be presently true, the statement concerning God’s foreknowledge will not be temporally necessary, its relation to the past notwithstanding. Yet, all this is quite consistent with saying that this statement is determined1 to be presently true inter alia in virtue of there being, 49 days from now, the fact that a sea battle is then raging in the Gulf of Aden.

To be sure, if one thinks that it is part of the very concept of truth that whenever a statement is true it is determined2 to be true, then ‘p is determined1 to be true at t’ will also entail ‘p is determined2 to be true at t’, already because the former entails that p is true at t. The contrast between these notions of truth-determination will then be lost. However, there is nothing that would force such a conception of truth upon us (cf. Greenough 2008). So if one wishes to exploit the contrast between truth-determination1 and truth-determination2 in the way suggested, this tells against adopting such a conception of truth. (For further discussion, see next section).

Determinism

According to one attractive and initially plausible conception of causation, if c is a cause of e, e would not occur if c had not occurred (cf. Lewis 1986).Footnote 2 If every event has a cause and is a cause in this sense, then a difference in initial conditions implies a difference in terminal conditions: from each terminal condition, there is but one way back.Footnote 3 Determinism adds something distinctive to the causalist doctrine that every event has a cause and is a cause in this sense, viz. that for any event e and the conjunction of its causes C, C would not occur, if e was not going to occur. Thus, according to determinism, a difference in terminal conditions implies a difference in initial conditions: from each initial condition, there is but one way to go.Footnote 4 Generalising from talk about the occurrence of events to talk about things being thus and so, and assuming that natural laws are amongst the present facts, we may accordingly describe determinism as the view that, for every statement p and every time t, at t, past and present facts already jointly necessitate the truth of p or of its negation.Footnote 5 In particular, this is meant to apply to statements about the future.

By contrast, indeterminism is typically understood to be the doctrine that just as not all that has happened was bound to happen before it did, not all that will happen, if anything, is bound to happen before it does. Thus, indeterminists will typically deny that for every statement and every time, at that time, the present and past facts jointly necessitate the truth of that statement or of its negation, even if the former include the natural laws. In particular then, determinists will hold, while indeterminists will deny, that every future-tensed statement is, if presently true, determined2 to be presently true, that is, determined1 to be presently true in virtue of past and present facts alone.

In the light of the foregoing, determinism can be rendered more precise as follows. Say that the world is deterministic iffdf all of the following hold:

-

(1)

A given statement is true at t iff it is determined1 to be true at t.

-

(2)

Either a given statement is true at t or its negation is.Footnote 6

-

(3)

A given statement is determined1 to be true at t iff it is determined2 to be true at t.

Classically, (1), (2) and (3) are jointly equivalent to:

-

(4)

Either a given statement is determined2 to be true at t or its negation is.Footnote 7

Note that determinism, as defined, is compatible with:

-

(5)

For all t, all n > 0 and all tense-logically simple p, ‘n days from the present, p’ is determined1 to be true at t iff n days from t, ‘Presently, p’ is made true by some fact.

That is to say, determinists may allow for truth-making by future facts. What they will, however, insist on is that the future existence of such truth-makers, if any, is jointly necessitated by what is and what has been the case. This combination of ideas may not be the most parsimonious of views, but it is consistent nonetheless.Footnote 8 Since (5) is plausible quite independently from the issue about determinism, this is as it should be.

One might still wonder whether (4) gives full expression to determinism, since the definition of truth-determination2 clearly allows for present-tensed statements being determined2 to be presently true solely in virtue of facts that are present. In other words, it would seem that, for all that (4) implies, the present might have ‘popped into existence’ without being the outcome of any law-governed processes initiated in the past, and this would clearly be at odds with deterministic thinking.

However, if (3) holds, then any statement determined2 to be true at t thanks to truth-makers that are, at t, present will likewise be determined2 to be true at t thanks to truth-makers that are, at t, past. Thus, let ‘Presently, p’ be determined2 to be true at t because, at t, ‘Presently, p’ is itself made true by some fact. Given the truth-value link

-

(L) □(‘Presently, p’ is true at t ↔ ‘n days from the present, p’ is true at t′ (−n) days from t),

it follows that ‘n days from the present, p’ is determined1 to be true at a time -n days from t. By (3), ‘n days from the present, p’ is also determined2 to be true at a time -n days from t. For simplicity’s sake, assume that, -n days from the present, ‘n days from the present, p’ is itself made true by some fact. But then given (L), there is a statement s such that -n days from t, s is made true by some fact and necessarily, if s is true -n days from t, ‘Presently, p’ is true at t. Accordingly, ‘Presently, p’ is also determined2 to be true at t thanks to truth-makers that are, at t, past.Footnote 9

Indeterminism

All indeterminists reject (4) and so must reject at least one of (1), (2) and (3). (1) would seem to be unobjectionable to the indeterminist, as its right-to-left direction would seem trivial, while prescinding from worries about negative truth-makers, its left-to-right direction expresses the seemingly innocuous thought that, for any statement p and any time t, if p is true at t, then there is, was or will be something in virtue of which p is true at t. Thus, (1) is naturally seen as common ground between determinists and indeterminists. As we shall see in due course, however, matters are not necessarily what they seem.

What about (2)? It might be suggested that indeterminists may reject (2) while nonetheless accepting both (1) and (3). Let us see whether this is a tenable combination of views. Suppose then that (2) is said to fail because future contingents are neither true nor false. Let us for the moment assume that the right logic for the suggested view is Kleene’s strong 3-valued logic, and let us use T for (present) truth, F for (present) falsity and I for the status of being neither (presently) true nor (presently) false. Then we have the following (cf. Urquhart 1986: 76):

(a) T (A → B) | (b) F (A & B) | (c) I (A) |

F (B) | I (A) | Not: T (B) |

F (A) | F (B) | I (A → B) |

Accordingly, assume that there is some future contingent of the form ‘n days from the present, p’, with n > 0, such that neither this statement nor its negation is true at t0, where t0 is the present time. Assume that (1) is true, and so a fortiori true at t0:

-

(1)

A given statement is true at t iff it is determined1 to be true at t.

Given that (1) is true at t0, it is true at t0 that if ‘n days from the present, p’ is determined1 to be true at t0, then ‘n days from the present, p’ is true at t0. If a statement s is neither true nor false at t0, then it is false at t0 that s is true at t0. So by rule (a), it must then be false at t0 that ‘n days from the present, p’ is determined1 to be true at t0. It follows from the definition of truth-determination1, and so is true at t0, that if

-

(i′)

at some particular time t n days from t0 there is a fact that makes ‘Presently, p’ true,

and

-

(ii′)

necessarily, for every time t′, if ‘Presently, p’ is true at some time n days from t′, ‘n days from the present, p’ is true at t′,

then ‘n days from the present, p’ will be determined1 to be true at t0. By another application of rule (a), it follows that the conjunction of (i′) and (ii′) is false. Since (i′) is a future contingent, given that n > 0, (i′) should be regarded as neither true at t0 nor false at t0. Hence, by rule (b), we are committed to saying that (ii′) is false at t0.

What would it take for (ii′) to be false at t0? There would have to be a world centred on a time – its present time – such that the embedded generalisation is false in that world at that time. If the world is deterministic, then this generalisation will be true at its present time. So we must enquire whether the embedded generalisation may be false in an indeterministic world at its present time. Ex hypothesi, in such a world, (2) will fail for future contingents. Ex hypothesi, the actual world is a world of this kind. So if, by assuming no more about the actual world with its present time t0 than that it is indeterministic in this sense, we can show that the embedded generalisation is not false at t0, then we can show that (ii′) is not false at t0, in which case (1) is not true at t0.

Let us therefore ask what it would be for the embedded generalisation to be false at t0. There would then have to be a time t such that the conditional

-

(#)If ‘Presently, p’ is true at some time n days from t, ‘n days from the present, p’ is true at t

is false at t0, where again n > 0. For any time t, there is an m such that t is m days from t0, where m may be positive, negative or 0. Either n + m ≤ 0 or n + m > 0. Suppose that n + m ≤ 0. Then since ‘n + m days from the present, p’ will be either true at t0 or false at t0, either both the antecedent and the consequent of (#) will be true at t0 or both will be false at t. In either case, (#) will be true at t0. Suppose instead that n + m > 0. Then the antecedent of (#) will be a future contingent and so be neither true at t0 nor false at t0, while the consequent will not be true at t0. So, by rule (c), (#) will be neither true at t0 nor false at t0, and so not be false at t0. Therefore, we may conclude that (ii′) is not false at t0, whence it follows that it is not false at t0 that ‘n days from the present, p’ is determined1 to be true at t0. But then, contrary to what was assumed, (1) is not true at t0, and so not true.

What about (3)? Consider the following relevant instance:

-

(3′)

‘n days from the present, p’ is determined1 to be true at t0 iff ‘n days from the present, p’ is determined2 to be true at t0.

Proponents of the view under consideration are still, qua indeterminists, committed to taking future contingents to present counterexamples to (4) and so to rejecting the right-hand side of (3′) as false at t0. But we just saw that the left-hand side is not false at t0, whence by rule (a), (3′) cannot be true at t0. It follows that (3) cannot be true at t0 either.

So, assuming Kleene’s strong 3-valued logic, the suggested combination of (1) and (3) with the rejection of (2) proves untenable. At this stage, proponents of the suggested combination will deny that Kleene’s strong 3-valued logic is at all suited to give expression to their view. Instead they are likely to go for some kind of supervaluationism and define truth at a time as truth relative to all the possible courses of events that include what is past and present at that time and continue indefinitely into what is future at that time, consistently with what went on before (cf. Thomason 1970; MacFarlane 2008). Kleene’s strong 3-valued logic is ill-suited to formalise this supervaluationist conception. Thus, if F stands for superfalsity and I for the status of being neither supertrue nor superfalse, rule (b) will be invalid, and the conjunction of (i′) and (ii′) will be superfalse at t0 although neither (i′) nor (ii′) is superfalse at t0.

To see the latter, let t in (#) be identical to t0, that is, let m = 0. Then, at t0, all possible future courses of events are either such that both (i′) and the antecedent of (#) are false with respect to them, or such that both (i′) and the antecedent of (#) are true with respect to them, while the consequent of (#) is anyway superfalse at t0. Since there are, at t0, possible future courses of events of both categories, neither will (i′) be superfalse at t0 nor, at least for this choice of t and m, will (#) be superfalse at t0. But given that, at t0, all possible future courses of events are continuations of the same present and past, the reasoning a few paragraphs back already shows that (#) will not be superfalse at t0 for any other choices of t and m. The same will hold for all other centred worlds and their present times. So (ii′) will not be superfalse at t0.

So it seems that by opting for supervaluationism and adopting a logic suited to express it, proponents of the view under consideration can after all reconcile their rejection of (2) with their acceptance of both (1) and (3).

But now note that on this conception of truth as supertruth, not only will the distinction between truth-determination1 and truth-determination2 be obliterated (see section ‘Two Notions of Truth-Determination’), it will also follow that truth-value links of the kind exemplified by

-

(L) □(‘Presently, p’ is true at t ↔ ‘n days from the present, p’ is true at t′ (−n) days from t)

will no longer hold on conceptual grounds, for, on the conception of truth as supertruth, a future-tensed statement is true at a time only if, at that time, it is inevitable that the corresponding present-tensed statement is going to be true, and it is a substantial metaphysical thesis that, necessarily, what has come to be the case was inevitably going to be the case.

As we saw towards the end of the previous section, determinism, as defined by the conjunction of (1), (2) and (3), deserves to be called by that name only if it can avail itself of truth-value links of the kind (L) exemplifies. On the conception of truth as supertruth, that is, truth on all possible continuations of the past and present, (1) and (3) will be conceptually necessary, while (2) proves to be a substantial metaphysical thesis. So on that conception, the only tenet of determinism that has any metaphysical import is (2). But (2) alone will not be sufficient to license (L). What would rather be needed in order to license (L) is the necessitation of (2).Footnote 10 But on any adequate construal of determinism, determinists qua determinists should not be obliged to regard the metaphysical tenets defining their view as being themselves necessary. Thus, it should be open to them to concede that there are possible worlds that are indeterministic. Given □A ⊢ □□A, this problem is not solved by saying that determinism underdescribes determinism proper and that the central metaphysical tenet defining the latter should be the necessitation of (2) rather than simply (2).Footnote 11, Footnote 12

All in all, it would therefore seem most natural to assume that (3), far from being a conceptual truth, is one of the determinists’ central metaphysical tenets and that indeterminists should at least reject (3), whether or not they also reject (1) or (2).

However, there is still one pertinent view that suggests otherwise, viz. the radical view according to which there is no future at all.Footnote 13 On such a view, it is most natural to reject the inference from ‘∼(n days from the present, p)’ to ‘n days from the present, ∼p’, whenever n > 0 and p is tense-logically simple: if there is no time n days from the present, no statement implying that there is such a time will be true, and it is most natural to assume that both ‘n days from the present, p’ and ‘n days from the present, ∼p’ have this implication. Once this inference is rejected and all relevant statements of the form ‘∼(n days from the present, p)’, with n > 0, are accepted as true, (2) can be retained. But by the same reasoning, (3) turns out trivially true: if there are no future times, then there are no future facts and all statements of the form ‘n days from the present, p’ and their negations will accordingly be determined1 to be true iff they are determined2 to be true.

Whether (1) can be retained on such a view accordingly depends on whether there are any past or present facts whose existence necessitates that there are no future times. If there are such facts, the proclaimed end of time is compelled by what happens before it and so is inevitable, and this is surely a deterministic thought. If there are no such facts, by contrast, then it is consistent with what goes on before the end of time that time extends into the future, even if it does not so extend. So it seems that there are two versions of the ‘no future’ view, one that involves acceptance of (1) and one that involves its rejection. Only the latter qualifies as a version of indeterminism, which finding is in line with the definition of determinism given in the previous section.

Thus, our conclusion should be appropriately qualified: unless they opt for the radical‘no future’ view and so reject (1), indeterminists should at least reject (3). This is how indeterminism will be understood in the remainder of this chapter. Since rejection of (3) also suffices for indeterminism, and since (2) is well-entrenched and anyway consistent with the ‘no future’ view, I will, until further notice, only be concerned with forms of indeterminism that involve acceptance of (2).

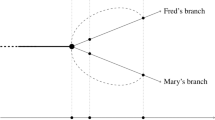

Indeterminism and the Thin Red Line

It is a common thought that an indeterministic universe is best modelled by tree-like structures. It is equally common to think of these tree-like structures as models of branching time, that is, as structures that reflect the structure of time and hence of temporal reality (cf. Thomason 1970; Belnap et al. 2001; MacFarlane 2008). As I shall argue in this section and the next, there is reason to think that these are inconsistent demands on what such tree-like structures should accomplish.

If, in accordance with the first demand, the many branches of the tree merely represent those continuations of present and past history that are consistent with the totality of present and past facts, the tree will represent a mere range of possibilities. As such, it suggests as yet nothing whatsoever about the structure of time – just as its being both possible that there is an accident ahead and possible that there is no accident ahead suggests nothing whatsoever about whether the road ahead forks. The existence of many branches is then quite consistent with the idea that there is now a unique answer to the question of what will come to be the case, even if what will come to be the case is not compelled by what is or has been the case. To infer from the observation that many future courses of events are consistent with what is or has been the case, that there is now no such unique answer, is either to succumb to deterministic reasoning or to rely on the indeterministic version of the ‘no future’ view. Yet, it was indeterminism, and not determinism, that was meant to be modelled by the tree-like structure, and the ‘no future’ view is anyway best represented by a decapitated trunk rather than a tree whose branches extend into the future. On this radical view, time itself would again be linear and not branching.

Belnap et al. argue that there is no Thin Red Line (TRL), marking out the one and only actual future. They ask, merely rhetorically, ‘what in the structure of our world could determine a single possibility from amongst all the others to be “actual”’, and go on to add that ‘as far as we know, there is nothing in any science that would help’ (Belnap et al. 2001: 162). This rhetoric makes perfect sense if ‘determine’ is here understood to mean the same as ‘determine2’ and any TRL would already have to be singled out by the totality of present and past facts alone, and so be a TRL2, for short. But once ‘determine’ is understood to mean the same as ‘determine1’ and the TRL is thought not to be singled out by past and present facts alone but only in conjunction with future facts, and so is thought of as a TRL1, the authors’ misgivings would seem entirely misplaced. (For a similar complaint, see Iacona, this volume.)

Surprisingly, however, Belnap et al. take their considerations to show that postulating a TRL1 is unfounded (Belnap et al. 2001: 135–36).Footnote 14 Worse still, at a later stage, they themselves suggest that in order to know the truth about what will come to be the case, one must wait and see until it has come to be the case (ibid.: 175–76). But then there would seem to be a TRL1 after all, viz. the course of those events that will have come to occur at the time at which we, or our successors, have waited long enough to be in a position to know that they were going to occur! Accordingly, and by the authors’ own lights, we should distinguish between TRL1s and TRL2s: even if there is no TRL2, there may nonetheless be a TRL1. If there is such a TRL1, then for all that has so far been said, time is linear and not branching.Footnote 15

A worry one might have is that once such a TRL1 has been postulated, it becomes difficult to see how we can be free to choose and act. If the future is presently determined1 to be a certain way, even if it is not compelled to be that way by any present or past facts, then how can my present acts have any impact on that future? And how can what I will do then be said to depend on my present choices? This worry can be answered as follows. If indeterminism reigns, there is indeed no basis for saying that whenever I presently act in a certain way my acts compel future events, or that whenever I will act in a certain way after presently choosing to do so that I will do so is compelled by my present choices. If ‘to have an impact’ means ‘to compel’, my present acts or choices can indeed have no impact on the future. But for all that, my present choices and acts may still make a difference by causing future events that otherwise would not be going to happen, including the actions I will perform (see section ‘Determinism’ above’). So, if ‘to have an impact’ just means ‘to be causally relevant’, which is by far the most natural reading, my present acts or choices can after all have an impact on the future. Since neither my choices nor my actions are compelled by what goes on before them, I am in a relevant sense free to make or perform them and so to impact on the future.

Dummett suggests that if, contrary to fact, I knew what was going to happen or what I was going to do, this knowledge would affect my present deliberations (Dummett 2004: 81). However, if what is going to happen counterfactually depends on what I presently do or choose to do, then I could not presently have that knowledge unless I nonetheless did or chose to do what I presently do or choose to do. At most, such knowledge would make my deliberations phenomenologically awkward. Maybe what will happen in part counterfactually depends on my giving in to fatalist thinking, but then again it may in part counterfactually depend on my resisting this temptation. Whichever case obtains, my foreknowledge would depend on what will happen, which in turn depends on whatever it is without which it would not be going to happen, and not the other way round. Recall that a statement like ‘Captain Nishky knows that a sea battle will take place’ is not determined2 to be true unless ‘A sea battle will take place’ is so determined2 (see section ‘Two Notions of Truth-Determination’). Postulation of a TRL1, rather than a TRL2, would thus seem to have no implications for human freedom.

Accordingly, when Diekemper argues that it would be bad enough for our self-conception as free subjects if the future was merely ‘contingently fixed’, where ‘contingent’ here contrasts with ‘compelled’, this thought must remain unpersuasive if ‘contingently fixed’ just means ‘determined1’ (see Diekemper 2007). Diekemper invokes time travel in order to drive his point home. But surely insofar as, for some such time traveller, part of the future is also his personal past, its description is in his personal time also determined2 to be true, and so the idea of equating the fixity of the future with its description being determined2 to be true, rather than merely being determined1 to be true, still stands. (The contrast between something’s being determined2 to be true in a time traveller’s personal time and its not being determined2 to be true in objective time is no more puzzling than the contrast between personal time and objective time that time travel requires, and it is Diekemper who invokes time travel.)

Arguably, this is not yet to answer Diekemper’s quest for an account of the asymmetry of fixity between past and future (Diekemper 2007), for, unless we are content to trivialise matters, we cannot simply equate the fixity of the past with its description being determined2 to be true: to say just this much at most implies that past-tensed statements are, if presently true, presently true in virtue of past facts. However, given the distinction between determinism and the causalist doctrine that every event both has a cause on which it counterfactually depends and is a cause on which other events counterfactually depend (see section ‘Determinism’), we may instead venture to say that the present past is fixed iff its present description is determined3 to be presently true, where a statement p is determined3 to be true at t iffdf there is a collection of statements Σ and a function δ from the members of Σ to numbers suitable for measuring temporal distances such that:

-

(i)

∀q∈Σ(∃t′ (t′ is δ(q) days from t & at t′, ∃f(q is made true by f)))

-

(ii)

□∀t′ [(∀q∈Σ(∃t″ (t″ is δ(q) days from t′ & q is true at t″))) → p is true at t′]

-

(iii′)

∀q∈Σ(δ(q) ≥ 0).

In other words, a statement is determined3 to be true at a given time just in case its truth at that time is necessitated by truth-makers that are, at that time, present or future but not past. The claim that the past is fixed in this sense is open to an indeterminist who accepts the causalist doctrine (see sections ‘Determinism’ and ‘Indeterminism’).Footnote 16

As we shall see in due course, however, under certain specifiable assumptions, the thought that the past is fixed in this more demanding sense conflicts with epiphenomenalism according to which there are past events that have had, and will have, no effects. Yet arguably, this is no objection to the cogency of the contemplated proposal, for, on the one hand, epiphenomenalism is itself a controversial doctrine which may have unexpected and controversial implications.Footnote 17 On the other hand, if the fixity of the past really consists in more than just the innocuous thought that past events are past, or that given how the past is we cannot undo it (Lewis 1986: 77–78) – which would either give us asymmetry on the cheap or symmetry on the cheap as soon as we said corresponding things about the future – an imperfect fit between what is past and what is fixedly past need not necessarily count against an explication of the latter.

Whether we think of fixity in general in terms of truth-determination2 and so regard it as trivial that the past is fixed, or whether we aim for something more ambitious and explain the fixity of the future, or rather the lack thereof, in these terms but the fixity of the past in terms of truth-determination3, either way there is no reason specifically to do with human freedom or the asymmetry of fixity that could oblige us to deny that there is a TRL1. If there is such a TRL1, however, then the tree-like structure, though apt to represent future possibilities, does not adequately reflect the structure of time or of temporal reality, which will then rather be linear.

There is a more indirect way of showing that, conceived as delineating a space of mere possibilities, the tree-like structure implies nothing about the structure of time or of temporal reality. For argument’s sake, assume that with the sole exception of the natural laws, only statements of the form ‘Presently, p’, with p being tense-logically simple, are ever made true by facts so that, for example, neither ‘Two days ago, a sea battle took place’ nor ‘Presently, more energy is released than was needed before e′ came to pass’ is ever made true, their being determined1 to be true notwithstanding. Now suppose we accepted epiphenomenalism and thus held that some event e, occurring in the past, has had, and will have, no effects whatsoever. Past-tensed statements about the epiphenomenon e, even if presently true, will not then be regarded as being determined3 to be presently true: whichever way the present and future facts are or will be, they could have come to be or be going to be that way consistently with different past histories – in some e occurred, in others it did not. If we wished to represent these past possibilities, we could use an upside-down tree that displayed backward branching. Would this make us inclined to say that the structure of time or of temporal reality exhibits backward branching? Hardly. After all, e did occur. But then by parity of reasoning, neither does the tree-like representation of future possibilities as yet have any implications for the structure of time or of temporal reality, for equally, whatever will be will be.

In order for the tree-like structure to have such implications, the many branches of the tree must receive a rather different interpretation. As we shall see in due course, once such an alternative interpretation is provided, the tree-like structure ceases to be a representation of an indeterministic universe.

Branching Time and Determinism

Suppose that time itself branches and so is not linear. If time exhibits forward branching at t, then, literally understood, for any time t′ which is n days from t, with n > 0, there will be a time t″ distinct from t′ which is also n days from t. The branches of the tree will then correspond to distinct time-series Π such that for any t belonging to Π and any n < 0 suitable for measuring temporal distances, there is a unique time n days from t and that time also belongs to Π, and for any two times t′ and t″ in Π, there is an m such that t′ is m days from t″. The first condition excludes backward branching, while the second ensures that all times in the series are connected. To call these distinct time series, and the events that occur at their respective members, equally real is then just as consistent as saying, on a linear conception, that it rains at t but does not rain at t′, where t′ is later or earlier than t.Footnote 18

The conception I shall call ‘branching time’ goes beyond this minimal characterisation in two respects. First, branching time implies that whenever branching occurs and time continues along distinct time series, there will be a qualitative difference between any two such time series in the sense that the courses of events that respectively unfold along these series differ. In other words, according to branching time, time never branches into numerically distinct but otherwise indistinguishable time series. On a tensed conception of facts, this will be straightforwardly so, whether one takes individual times as entities sui generis or rather identifies them with sets of tensed facts: the fact that t is present surely differs from the fact that t′ is present whenever t and t′ are numerically distinct. But even on a tenseless conception of facts (see footnote 1), it seems entirely unmotivated, and ontologically extravagant, to posit branching into qualitatively identical time series. So I shall take it for granted that this addition to the minimal characterisation of branching time is harmless.

Secondly, and slightly more contentiously, according to branching time, whether a time series is real solely depends on the consistency of what occurs in its course with the totality of past and present facts. For instance, whether or not a time series counts as real that has a time n days hence at which it rains as member will depend on whether the totality of past and present facts, including the laws, permit that at a temporal distance of n days it rains. If, for any of its members, what happens at those members is thus permitted, the time series is real and not merely possible. This would seem to be what one must say as soon as one takes the branches of the tree to represent more than merely possible continuations of the past and present (and this is precisely what proponents of the so-called many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics do say).

Of course, there is conceptual room for the idea that more than one but not all possible continuations of the past and present are real. We would then still have branching as minimally characterised, and so there would be no Thin Red Line. But a proper part of the crown of the tree would still be marked out as real, and so, in a sense, there would be many thin red lines. Thus, for example, on a view such as this, even if, for all positive integers k with k < 6, it is consistent with the past and present that one day from the present k goals are scored, it may nonetheless be that there is a time one day from the present at which exactly three goals are scored and such a time at which exactly five goals are scored, but no such time at which exactly four goals are scored. But if, as we have assumed, all the nomological constraints are to be found amongst the present and past facts, it is hard to make sense of this suggestion – for neither the topology of time, nor the totality of present and past facts, nor their combination can explain both (i) why there is no time one day from the present at which exactly four goals are scored, if there is a time one day from the present at which exactly three goals are scored, and (ii) why there is a time one day from the present at which exactly five goals are scored, even if there is a time one day from the present at which exactly three goals are scored. On the linear conception of time, (i) is true and easily explained by the topological structure of time, while (ii) is false and a fortiori in no need of explanation. According to branching time, (ii) is true and explained in terms of both the initial conditions and the topological structure of time, while (i) is false and a fortiori in no need of explanation. The hybrid view according to which time branches into many thin red lines is committed to the possibility of pairs of true conditionals of this kind, but unable to account for their truth. In any case, to the best of my knowledge, nowhere in the extant literature has such a hybrid view ever been defended, which is why I take branching time to be the only relevant branching view to be addressed.

Let us now say that a statement s is genuinely future-/past-/present-tensed iffdfs is equivalent to some statement of the form ‘n from the present, p’, with p being tense-logically simple and n being positive/negative/zero (cf. Prior 1967: 122–26). It is then a consequence of branching time, as characterised, that genuinely future-tensed statements become systematically ambiguous.Footnote 19 Thus, we must now distinguish between at least three readings. On the first reading, such a statement is equivalent to ‘For some time t n days from the present, at t, p’. On the second reading, it is equivalent to ‘For all times t n days from the present, at t, p’. On the third reading, at last, it is equivalent to ‘At the time n days from the present, p’ and hence to ‘There is a unique time n days from the present, and for any time t n days from the present, at t, p’. As long as time was assumed to be linear, these readings could be treated as equivalent, and consequently there was no need to distinguish between them. But things are importantly different as soon as time is taken to exhibit forward branching. (By contrast, for n ≤ 0, the equivalences will then still hold.)

There is, however, a fourth suggested reading which deserves comment, even if only for the purpose of setting it aside. Belnap et al. take (unembedded) genuinely future-tensed statements to be true only relative to a specified history parameter (or in my parlance, a specified time-series parameter) (Belnap et al. 2001: 141–56). Accordingly, (unembedded) genuinely future-tensed statements are treated like open sentences whose only free variable ranges over histories (or in my parlance, time series). Thus, ‘n days from the present, p’, with n > 0 and p being tense-logically simple, can be read as ‘At the time n days from the present on Π, p’, where ‘Π’ occurs free. If time really exhibits forward branching, the context of use will fail to fix a unique value for ‘Π’, and consequently (unembedded) genuinely future-tensed statements will lack a truth value.

As Belnap et al. (2001: 156–60) are aware, it is difficult to square this fourth reading with the idea that genuinely future-tensed statements are ever assertable. Their solution to this problem follows a suggestion made by Prior (1967: 131) and likens assertions to bets. The authors argue that the assertoric content of a genuinely future-tensed statement ‘is the sort of thing that can be borne out or not, depending upon what comes to pass’ (Belnap et al. 2001: 175). And now, just as ‘it makes sense to wonder about what history has not yet decided as long as history will decide the matter’ (Belnap et al. 2001: 171), betting on a certain future outcome makes sense as long as history will decide the matter. And according to the authors, history will decide the matter: ‘time will tell whether we arrive at a moment at which the truth value (at the moment of assertion) becomes settled’ (Belnap et al. 2001: 175), while to claim of two future possibilities that they ‘will each be realized’ is to claim ‘an absurdity’ (Belnap et al. 2001: 207). Given what was said in the previous section about the distinction between TRL1s and TRL2s, these afterthoughts make their preferred reading of genuinely future-tensed statements entirely unmotivated.Footnote 20 But more importantly, as the last quotation makes clear, the account of assertoric content with which this reading is supposed to be combined is at odds with branching time. So at least in the present setting, I take this to be sufficient reason to disregard the fourth reading of genuinely future-tensed statements that Belnap et al. propose.

Accordingly, consider the first of the three initially mentioned readings and thus statements of the form ‘For some time t n days from the present, at t, p’, where p is tense-logically simple and n > 0. Recall that, according to branching time, anything that, consistently with the present and past facts (including the laws), can happen n days hence does happen at some future time n days from the present: every nomological future possibility is in fact realised on some time series. Let A be the conjunction of all the laws conjoined with the claim that they are laws and nothing else is. Let B be the conjunction of all nomologically contingent genuinely past- and present-tensed statements true at t. Let ‘Ttα’ be short for ‘α is true at t’. Now assume C to be a statement of the form ‘For some time t′ n days from the present, at t′, p’, with n > 0 and p being tense-logically simple. Assume that ‘Tt(A & B & C)’ is consistent. Then branching time entails that ‘TtA → (TtB → TtC)’ holds.Footnote 21 branching time should itself be nomologically necessary and so be entailed by A. Accordingly, given that ‘Tt(A & B & C)’ is necessarily consistent if consistent at all, the conditional ‘TtA → (TtB → TtC)’ should likewise be nomologically necessary and so be entailed by A. Accordingly, given that A, if true, is always true, ‘TtB → TtC’ will be nomologically necessary. Given how A was defined, to render A true, a metaphysically possible world must be a nomologically possible world. Consequently, ‘TtA → (TtB → TtC)’ will be metaphysically necessary, and so will be ‘TtA & TtB → TtC’. Insofar as both A and B are determined2 to be true at t, so will be C. Since ‘TtC’ holds only if ‘Tt(A & B & C)’ is consistent, C is true at t iff C is determined2 to be true at t. Given that consistency claims are bivalent, so are statements like C.

As a corrollary, given that C is true at t iff ‘Tt(A & B & C)’ is consistent, and that ‘∼C’ is true at t iff C is not true at t, ‘∼C’ is true at t iff ‘Tt(A & B)’ entails ‘Tt(∼C)’. Accordingly, ‘∼C’ is true at t iff ‘∼C’ is determined2 to be true at t. But ‘∼C’ is equivalent to a statement of the form ‘For all times t′ n days from the present, at t′, q’, with n > 0 and q being tense-logically simple. So given branching time, determinism applies to all genuinely future-tensed statements on both their first and their second readings.Footnote 22

Let us lastly consider statements of the form ‘At the time n days from the present, p’, with p being tense-logically simple and n > 0. If t does not branch in the sense that there are no two distinct times which both are n days from t, then at t such a statement will be equivalent to a statement of the form ‘For some time t′ n days from the present, at t′, p’ and so, by the reasoning above, will both be bivalent and be true at t iff determined2 to be true at t. By contrast, if t does branch in the sense that there are two distinct times which both are n days from t, then the definite description ‘the time n days from the present’ will fail to denote at t, and hence statements of the form ‘At the time n days from the present, p’ will be uniformly untrue at t and a fortiori not be determined2 to be true at t. Note that this will not conflict with (2) and its underlying identification of non-truth with falsity, as the negations of statements of that form are of the form ‘∼(There is a unique time n days from the present, and for any time t′ n days from the present, at t′, p)’, and given branching we can no longer infer from the latter that ‘At the time n days from the present, ∼p’ holds, even if we take time to extend indefinitely into the future.Footnote 23

What remains to be shown is that these negations themselves are true at t iff determined2 to be true at t. Given branching time, t branches in the aforementioned sense because there is a tense-logically simple q such that both the truth at t of ‘For some time t′ n days from the present, at t′, q’ and the truth at t of ‘For some time t″ n days from the present, at t″, ∼q’ are consistent with ‘Tt(A & B)’. Whether this is so, however, will already be settled by facts that obtained before t. But then, whether or not t branches in that sense, statements of the form ‘At the time n days from the present, p’ as well as their negations will both be bivalent and be true at t iff determined2 to be true at t. Consequently, (4) will hold for all statements of the form ‘At the time n days from the present, p’, with p being tense-logically simple and n > 0, and so will (3). Thus, given branching time, determinism also applies to statements of this form.

We can therefore conclude that it follows from branching time that genuinely future-tensed statements are bivalent and are true at t iff determined2 to be true at t, on all of the aforementioned three readings. Hence, branching time implies determinism.

Determinacy by Truth-Determination (and Indeterminacy by Lack Thereof)

Recently, Barnes and Cameron have proposed an account of determinism and its relation to the open future that crucially differs from the one advocated here (Barnes and Cameron 2009). In this section, I argue that their elucidation of what it is for the future to be open needs backing by some antecedent notion of what it is for a world description to be determinately true of the actual world. Of the two notions introduced in the first section, only the notion of truth-determination2 will serve this purpose. However, since Barnes and Cameron claim determinism to be compatible with the open future, it transpires that they must either reject the characterisation of determinism given in the section ‘Determinism’, or else deny that truth-determination2 is the right notion to back up their characterisation of the open future. In the next section, I will accordingly first review and criticise their own preferred characterisation of determinism and then consider what alternatives to the notion of truth-determination2 they might appeal to in order to substantiate their account of the open future.

According to Barnes and Cameron, the possible continuations of the past and present ought to be conceived as possible ways the one and only concrete world @ might turn out to be in the future. Let {Future} be the set of all such possible ways, agreeing on the present and past, which, for convenience’s sake, we might think of as Priorian world propositions (Barnes and Cameron 2009: 295–96; cf. Prior 2003). Barnes and Cameron contend that ‘it’s determinately the case that exactly one of the worlds in {Future} is actualised’, while for any w in {Future}, it is indeterminate whether w is actualised (Barnes and Cameron 2009: 296), where here ‘actualised’ just means ‘true of @’. This is what they take the open future to consist in. Just before making this claim, they contend that the operators ‘it is determinately the case’ and ‘it is indeterminate whether’ underwrite the following equivalences (Barnes and Cameron 2009: 295):

-

(6)

It is determinately the case that p iff for all w in {Future}, w says that p.

-

(7)

It is indeterminate whether p iff for some w in {Future}, w says that p, and for some w′ in {Future}, w′ says that not-p.

Given (6) and (7), it is perfectly intelligible how it may be determinately the case that exactly one member of {Future} is actualised, while for any such member w, it is indeterminate whether w is actualised. Applying (6) and (7) to the case at hand, we get

-

(8)

For all w in {Future}, w says that exactly one of the members of {Future} is actualised, and for any w′ in {Future}, there is a w″ in {Future} such that w″ says that w′ is actualised, and there is a w¢¢¢ in {Future} such that w¢¢¢ says that w′ is not actualised.

(Naturally, if w says of w′ that it is actualised, then w = w′.) According to Barnes and Cameron, then, (8) is apt to capture the thesis that the future is open.

However, even if every w in {Future} says that exactly one member of {Future} is actualised, that is surely not what metaphysically determines it to be the case that exactly one member of {Future} is actualised. World propositions may be complete in that for any p, they either entail p or entail its negation, but they are surely not self-authenticating (cf. Frege 1892 on whether a thought can ever contain its own truth value). A fortiori that they are unanimous that exactly one member of {Future} is actualised cannot be what makes it, in any metaphysical sense, determinately the case that exactly one such member is actualised. Similarly, the mere fact that there is no member of {Future} that is said by all members of {Future} to be actualised cannot be what precludes that it is metaphysically determined of any particular such member that it is the one and only member that is actualised, and so cannot be what makes it metaphysically indeterminate which member is actualised. (The fact that each of the candidates for being in charge proclaims ‘I am in charge’ does not preclude its being determinately the case that John, and only John, is in charge, just as the fact that each of the candidates says ‘One of us is in charge’ does not determine that anyone is.)

Of course, given that {Future} is the set of all possible, yet mutually incompatible ways @ might continue to be and given that @ must continue to be one way or other, it indeed follows from the fact that every w in {Future} says that p, that p is determined to be actualised (i.e. to be true of @).Footnote 24 But that p is determined to be actualised does not consist in this unanimity. The matter comes out more starkly in the case of indeterminacy: it simply does not follow from the fact that some members of {Future} say that p, while others say that ∼ p, that p is not determined to be actualised (i.e. determined to be true of @).

In fairness to Barnes and Cameron, it must be noted that they consider (6) and (7) merely as elucidations of their preferred notions of metaphysical determinacy and indeterminacy, and not as analyses. Yet, as long as we lack any insight into the relation that a member of {Future} must bear to @ in order for it to be determined to be true of @, we have no guarantee that these elucidations are even extensionally adequate. Accordingly, we must look beyond (6) and (7) in order to get a clearer view of what these equivalences are meant to elucidate.Footnote 25

A natural way to conceive of the relation of being determinately actualised is in terms of truth-determination. According to this suggestion, the authors’ characterisation of the open future can be restated thus:

-

(9)

The disjunction of all the members of {Future} is determined to be presently true, while none of its disjuncts is determined to be presently true.

Here, ‘determined’ can again be understood in either of two ways. It may mean the same as ‘determined1’, as the latter was defined in the first section, or it may mean the same as ‘determined2’, as there defined. Thus, we may either consider all facts, past, present and future, or restrict attention to those facts that constitute @ either at the present time or at past times, while excluding those facts, if any, that only come to constitute @ in the future. Only on the latter reading is there any reason to maintain that none of the members of {Future} is determined to be presently true, for, as Barnes and Cameron remark, ‘the unfolding of the future settles which truth value [presently made future-tensed statements] in fact have’ (Barnes and Cameron 2009: 298; see also Belnap et al. 2001: 171, 175–76, where a similar thought is broached). Pace the authors’ avowed primitivism about metaphysical determinacy and indeterminacy, their conception of the open future would thus naturally be seen as lending itself to recapture in terms of truth-determination2.

Determinism, Metaphysical Indeterminacy and the Open Future

It would accordingly appear that all is well. But all isn’t well, for Barnes and Cameron go on to argue that the present truth of some future-tensed statements (unaffected by semantic indecision, presupposition failure and the like) may fail to be settled by past and present facts, and yet determinism holds (Barnes and Cameron 2009: 300). Thus, provided that the interpretation offered in the previous section is correct, they are bound to reject the characterisation of determinism given in the section ‘Determinism’ above.

Using the terminology introduced in the first section, we may say that, according to Barnes and Cameron, determinists merely claim that if all the present- and past-tensed statements (and laws) are determined2 to be presently true, then the present truth of all future-tensed statements will likewise be determined2. On this construal, determinism is alleged to be consistent with admission of some genuinely present- and past-tensed statements failing to be determined2 to be true.

It is, however, hard to make sense of this, for, plausibly, genuinely present- and past-tensed statements are determined1 to be presently true only if they are also determined2 to be presently true. If (2) is to be retained, and the authors are adamant about this (Barnes and Cameron 2009: 296–97), (1) must accordingly fail:

-

(1)

A given statement is true at t iff it is determined1 to be true at t.

-

(2)

Either a given statement is true at t or its negation is.

But then, some present- or past-tensed statements would have their truth value groundlessly, in Sorensen’s sense of ‘groundlessly’, and this would make their indeterminacy quite unlike the indeterminacy of future-tensed statements, contrary to what Barnes and Cameron suggest (Sorensen 2001; Barnes and Cameron 2009: 303), for recall that with respect to the latter kind of statements the authors claim that ‘the unfolding of the future settles which truth value they in fact have’ (Barnes and Cameron 2009: 298). The TRL1 would thus be said to extend only into the future, while it frayed out in the other direction. This is certainly nothing determinists are willing to buy: if the TRL1 extends into the future and (2) is assumed to hold, then determinists will say that for any p and any n and m such that n ≥ m > 0, either ‘m days hence, n days ago, p’ is determined2 to be presently true or ‘m days hence, n days ago, ∼p’ is determined2 to be presently true, which excludes the possibility that neither ‘n − m days ago, p’ nor ‘n − m days ago, ∼p’ is determined2 to be presently true. But even if Barnes and Cameron’s remark only applies to genuinely future-tensed statements (as they were defined in the last but one section), it is highly unlikely that determinists are willing to reject the causalist doctrine according to which every difference in initial conditions implies a difference in terminal conditions, so that from every terminal condition there is but one way back (see section ‘Determinism’ and footnote 4).

To be sure, Barnes and Cameron do not themselves invoke talk about truth-determination1 or truth-determination2. Yet, we may still bring out a relevantly similar tension once we revert to the authors’ own preferred terminology. Given how {Future} was defined, then in the light of (6), for all tense-logically simple p and all n ≤ 0, it is the case that n days from the present, p iff it is determinately the case that n days from the present, p. As already mentioned, Barnes and Cameron accept (2) (Barnes and Cameron 2009: 296–97). Yet, if (2) holds, then, for all tense-logically simple p and all n ≤ 0, either it is determinately the case that n days from the present, p or it is determinately the case that n days from the present, ∼p.Footnote 26 Accordingly, when Barnes and Cameron argue that it may in part be indeterminate what the present or past is like, they evidently have another notion of ‘indeterminate’ in mind.

If one consequently replaced reference to {Future} in (6) and (7) by reference to the set of all the possible ways @ might be in the past, present and future, then only necessary propositions would ever be determinately true. Consequently, it would then be indeterminate whether I had breakfast this morning – which would hardly be a desirable result. But irrespectively of the oddity of such claims about the present or past, the whole enterprise of giving sense to the openness of the future would thus be undermined: certainly, as long as we wish to resist the radical view according to which there is no future at all, we want to say things like, ‘When I am masticating my buttered toast, it may then still be open whether I will have a fruit afterwards, but it is settled that the buttered toast will be mash’. I cannot have my toast and eat it, as it were, while I still can eat the toast and have a fruit. Yet, since ‘The toast will be mash’ is neither metaphysically nor nomologically necessary, it would have to be just as open whether the toast will be mash as it is open whether I will finish off with a banana. This is surely nothing Barnes and Cameron wish to hold.

In the previous section, it was argued that (6) and (7) presupposed a conception of what it is for a world proposition to be determinately actualised. However, as argued three paragraphs back, replacing talk about what is determinately the case in the sense of (6) by talk in terms of truth-determination2 leads to trouble once we try to make sense of the alleged compatibility between determinism and denial of (4):

-

(4)

Either a given statement is determined2 to be true at t or its negation is.

But then it remains thus far unclear what notions of determinacy and indeterminacy Barnes and Cameron do have in mind.

Other work by Barnes and Cameron suggests that what the authors here have in mind is rather that it is indeterminate whether a given statement is determined to be true, in one of the two senses of ‘determined’ (Barnes 2010; Cameron 2009). If both (1) and (2) are assumed to hold, there are then two possibilities: either it is claimed that it is determinate which facts there are, were or will be, but indeterminate whether they determine p to be true or rather determine ∼ p to be true, or else it is claimed that it is indeterminate which facts there are, were or will be. It remains to be seen whether these notions of indeterminacy of truth-determination are of any use in the context of discussions about the open future.

The first option either collapses into a claim of semantic indeterminacy about fact descriptions or else misconstrues the nature of facts and of truth-determination: for the fact that presently, q to make ‘Presently, q’ true at t, all that is required is that that fact exists at t, and truth-value links will then ensure that all relevant past- and future-tensed statements are determined to be true at the correspondingly relevant times (cf. Correia and Rosenkranz 2011: 89).

The second option, favoured by both Barnes and Cameron, is again prone to collapse into a claim of semantic indeterminacy about fact descriptions, if read as suggesting that for some facts f and for all q (or all q in some nomologically relevant range), f does not determinately satisfy ‘is a fact that presently q’. Alternatively, if it is claimed that there is no such semantic indeterminacy involved, acceptance of both (1) and (2) will then imply commitment to the idea, explicitly endorsed by Cameron (2009), that it may be indeterminate whether the fact that presently q exists at t, while it nonetheless does exist at t. But whatever ‘indeterminate’ might here be understood to mean, given what was just said about the nature of facts and of truth-determination, this fails to substantiate the claim that it is in any relevant sense of ‘open’ open whether ‘Presently, q’ is determined to be true at t.

The topic of metaphysical indeterminacy is intricate, and a thorough discussion of it would take us too far afield. Suffice it to say that for reasons similar to those mentioned in the previous section, indeterminacy of truth-determination is not yet adequately captured by (6) and (7), and that it is anyway not the kind of indeterminacy relevant for capturing the open future.

Conclusion

I take all this to suggest that, for want of any clear alternative, the characterisations of determinism and indeterminism given in the sections ‘Determinism’ and ‘Indeterminism’ respectively’ are after all the correct ones when it comes to discussions about the open future, and that the open future is best conceived in terms of indeterminism thus characterised. Whether one opts for determinism or for indeterminism, one may consistently take time to be linear and not branching. If the future is said to be open merely in the sense of not being compelled by present or past facts alone, then the open future, while inconsistent with admission of a TRL2, is nonetheless consistent with admission of a TRL1, which latter rules out branching time. By contrast, if the future is said to be open in a sense of ‘open’ that is incompatible with there being any TRL1, then there is no future and the best representation of this idea is by means of a decapitated trunk rather than a branching tree. In neither case does indeterminism suggest that time itself branches. On the contrary, as argued in the section ‘Branching Time and Determinism’, on a reasonable account of what the conception of branching time involves, indeterminists have reason to deny that time branches and should rather consider the tree-like structure as representing nothing more than a range of possibilities one, and only one, of which is determined1 to be actual, provided that there is any future at all.

Notes

- 1.

Assuming facts to be tensed has the advantage that we can sensibly talk about facts existing at certain times but not at others, for example, at past times but not at future times. Yet, most of what follows could be recast in terms of tenseless facts that have the relevant times as constituents. However, such reformulations would be unnecessarily cumbersome. For suitable accounts of tensed facts, see Correia and Rosenkranz 2011.

- 2.

As Lewis notes, this at most holds for cases of immediate causation, as we wish to say that c causes e if c causes e′ which in turn causes e. In other words, we take causation to be transitive, while counterfactual dependence is not. The obvious remedy is to define causation in terms of causal chains, that is, chains of pairwise counterfactually dependent events (Lewis 1986: 167). For simplicity’s sake, I will stick to the above formulation. Consequently, ‘cause’ should here be taken to mean ‘immediate cause’. For further provisos, see next footnote.

- 3.

This reasoning relies on ‘□((∼A □→ ∼B) → (B → A))’ which is uncontroversial given only that no world is closer to the actual world than the actual world itself. Note that since ‘→’ is transitive, the existence of causal chains involving intermediate causes will leave the claimed inference from terminal conditions to initial conditions unaffected. See previous footnote.

As Lewis reminds us, there are likely to be cases of causal preemption (and overdetermination) so that c would have caused e if c′ had not occurred. In such cases, we would still want to be able to say that c′ causes e, although there is no counterfactual dependence (Lewis 1986: 171–72). The causalist doctrine mentioned in the text does not exclude such cases, even if they render doubtful that the suggested counterfactual characterisation captures our ordinary concept of causation, for note that causal preemption and overdetermination are relations between particular events. Yet, even if c′ preempts c’s causing e, or c and c′ overdetermine e, so that, either way, it is not the case that e would not have occurred if c′ had not occurred, there may still be a c" such that e would not have occurred without it and an e′ such that it would not have occurred without c′. To skirt any further issues, let ‘(immediate) cause’, as it occurs in the causalist doctrine, henceforth be a technical term understood to imply counterfactual dependence.

- 4.

Often, determinism is identified with the combination of this thought and the causalist doctrine. However, since indeterminists may endorse the latter, it will be more convenient to reserve ‘determinism’ for the former. (As we shall see in section ‘Branching Time and Determinism’ below, if time exhibits forward branching, the ‘one way to go’ from the initial conditions may consist in a unique manifold of continuations spread across distinct time-series just like the crown of a tree.)

Note that I here diverge from Lewis who explicitly denies that determinism should be understood in either of these ways because, for him, the direction of time is to be explained in terms of causation and causation is analysed in terms of counterfactual dependence (see Lewis 1986: 32–38, 167). By contrast, merely to say, as I do, that causation implies counterfactual dependence neither precludes the thought that the past and present might also counterfactually depend upon the future, nor renders that thought incompatible with the idea that time’s arrow can be explained in terms of causal asymmetry.

- 5.

I here take it that, according to determinism, the connection between initial and terminal conditions is law-governed so that, where A states the initial conditions and B states the terminal conditions, if ‘∼B ʿ→ ∼A’ holds in the actual world, it will also hold in all nomologically possible worlds, and consequently that if ‘∼B ʿ→ ∼A’ holds, ‘A → B’ will hold in all nomologically possible worlds (see last but one footnote). If A itself entails the conjunction of the relevant laws as well as the claim that they are laws and nothing else is, ‘A → B’ will furthermore be necessary simpliciter: any metaphysically possible world satisfying A will then be a nomologically possible world. See footnote 8 below for the assumption that A, though made true by present and past facts alone, can nonetheless be understood to entail the relevant laws as well as the claim that they are laws. For the thought that the causalist doctrine need not issue in a corresponding claim of necessitation, see footnote 16.

- 6.

I here ignore statements affected by semantic indecision, presupposition failure, and comparable linguistic or pragmatic shortcomings. I will also ignore the intuitionists’ view according to which there is a gap between affirming that no statement is such that neither it nor its negation is true at t and affirming (2). There is no evident reason why there shouldn’t be an intuitionistically acceptable version of determinism that foregoes commitment to (2) but affirms its double negation instead. Accordingly, any indeterminist view that takes issue with (2) will here be conceived of as taking issue with its double negation, too.

- 7.

See previous footnote.

- 8.

It might be thought that determinism, as defined, is after all incoherent because it will have to postulate laws which connect the past and present with the future and, as such, are partly determined1 to be true by what will be the case in the future. If so, what will be the case in the future cannot be said to be determined2 to be true, that is, determined1 to be true by present and past facts alone (cf. Barnes and Cameron 2009: 300). However, rather than confuting the present characterisation of determinism, this consideration suggests that determinists had better reject the Humean regularity-based conception of laws and instead conceive of laws as facts relating (potentially uninstantiated) properties or relations. There are independent reasons for construing laws in these terms (cf. Dretske 1977; see Maudlin 2007 for a primitivist alternative to Dretske’s account). Plausibly, if laws are construed as facts relating properties and relations, the existence of such facts metaphysically entails that they are laws.

- 9.

The proof assumes that for any time t, there are times earlier than t. Accordingly, if time has a beginning, the conclusion cannot be proved for all times. But then, under that same assumption, there is no reason to think that determinism involves the idea that, for all times t, including the first time, what is true at t is predetermined by what was the case before t.

- 10.

On the intuitionists’ view, less is needed, viz. merely the necessitation of ‘No statement is such that neither it nor its negation is true at t’. However, as already indicated in footnote 6, once intuitionism comes into view, there is no evident reason why determinism must be construed as involving (2) rather than this (intuitionistically) weaker tenet. The present considerations would mutatis mutandis carry over to this (intuitionistically) weakened version of determinism.

- 11.

Federico Luzzi suggested to me that the present issue might be resolved by conceiving of determinists and indeterminists as having a disagreement about what the determinists’ metaphysical tenets are: while the indeterminists regard (3) as a conceptual truth and take the determinists’ controversial thesis to be (2), the determinists themselves may rather regard (2) as a conceptual truth and take their controversial thesis to be (3). determinists would not then be pictured as treating their central metaphysical tenet as necessary. On this way of construing the debate, however, not only would each party charge the respective other with conceptual error; the conception of truth as supertruth would furthermore involve a bias in favour of indeterminism, given only that it is implausible to think that determinism is true only if necessary. There would thus seem to be no neutral ground from which to argue, as is familiar from the debate concerning logical revisionism. As long as alternative construals are available that do not have this consequence, abandoning the idea of a neutral standpoint would seem to be undesirable already for methodological reasons.

- 12.

Even if we replaced clause (iii) in the definition of truth-determination2 by ‘qÎΣ(δ(q) < 0)’, thereby sidestepping the difficulty mentioned towards the end of the previous section, and understood determinism’s tenet (3) accordingly, it would still, thanks to clause (ii) of that definition, hold that determinism requires necessary links between the present truth of present-tensed statements and the past truth of future-tensed statements, which unnecessitated (2) cannot deliver. In any case, though, after the envisaged redefinition of truth-determination2 and of determinism’s tenet (3), the conception of truth as supertruth would imply that (2) is not the only metaphysically controversial tenet the determinist accepts: if ‘0 days from the present, p’ is true at t0, then, insofar as both (1) and (3) hold, ‘n days from the present, p’ will have to be true at t-n, for some positive n. But what holds on all possible continuations of both what is past at t0 and what is present at t0 may not hold on all possible continuations of both what is past at t-n and what is present at t-n. Accordingly, if truth-determination2 and determinism’s tenet (3) were redefined in the way suggested, supervaluationist indeterminism would no longer be a position of the kind we are here considering, that is, a position that accepts (1) and (3) but rejects (2). Thanks to Graham Priest for pressing me to elaborate on this point.

- 13.

There are fairly obvious problems with ‘alwaysing’ a view such as this. But even if it cannot be part of such a view that it is available at each time and so available at earlier times, this does not alter the fact that, at each time, some view of this kind is available (albeit one which is no longer available at later times, if any).

- 14.

Belnap et al. identify the doctrine of the open future with ‘the view that in spite of indeterminism one neither needs nor can use a Thin Red Line’, where the latter is meant to refer to a TRL1 (Belnap et al. 2001: 136). But then why isn’t this suggestive of a decapitated trunk rather than a branching tree? The answer presumably is that only a branching tree can represent future possibilities. But this, as argued, is not suggestive of branching time and neither rules out, nor makes it superfluous to think, that there is a TRL1.

- 15.

See footnote 20 for further discussion. MacFarlane seeks to discredit assumption of a TRL1 by suggesting that it rests on the confused idea that we move through time as a car moves along a road (MacFarlane 2008: 85–86). I fail to see any such connection.

- 16.