Abstract

Italian kindergartens are world-renown and they have developed within the context of educational reform in Italy that has occurred since the 1940s. In this chapter, three types of kindergartens are described: private, state-funded, and municipal. Included is a brief history of the evolution of kindergartens, description of the learning environments, teacher qualifications, and child populations. A summary of the findings of the comparative Global Guidelines Assessment study of kindergartens in Bologna, Parma, Modena and Reggio Emilia is also presented.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Globally, early childhood educators have been influenced by the municipally operated Reggio Emilia preschools of northern Italy (Edwards et al. 1998; New 1990, 1993). There are, however, three types of preschool settings in Italy—state, municipal, and private. The last year of the preschool experience is equivalent to the kindergarten year in the United States, and the preschool programs are also referred to as kindergartens. Italy is a progressive country that has embraced quality early childhood programs beginning with the post-World War II (WWII) era. Italy offers government-supported preschool education with over 94 % attendance; the program is full-day, five days a week and operates from early September through the end of June (Corsaro et al. 2002, p. 335) (Fig. 5.1).

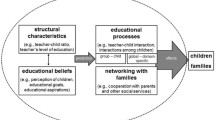

The authors of this chapter conducted a pilot study of the ACEI Global Guidelines Assessment instrument in the northern Emilia Romagna region of Italy, including teachers from all three types of kindergarten classrooms. In this chapter the authors discuss kindergarten environments for young children 3 to 6 years of age. In addition, the results of a study of classroom environments using the global guidelines in these three kindergarten types are presented. Kindergarten classrooms in the northern sector of Italy—Bologna, Modena, Reggio Emilia, and Parma—are described in this chapter.

Historical Perspective

Italy is a democratic republic organized on the basis of a constitution developed in 1946–1947, coming into force in January 1948 (OECD 2001, p. 8). Two major sources of influence have shaped Italy’s economic resources: WWII and the European Union. In order to understand the kindergartens of northern Italy, it is important to also understand their historical, political, and economic contexts. WWII marked an important time for Italy, and the emergence of kindergartens for young children reflected a commitment to both social capital and economic investment. During the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, several progressive social policies were implemented to improve the living conditions of women, families, and children (New 1993). The legislation of this era represented significant efforts to advance women’s rights (OECD 2001; New 1993). The progressive early education settings in Italy that developed were the result of fierce political struggles involving political entities representing the left and the right, labor unions, and the Catholic Church (Corsaro et al. 2002, p. 336). Within this national political and social context, regional and grass roots educational experimentation arose in the Emilia Romagna area of northern Italy. The care and education of young children were increasingly seen as a public concern and responsibility. Italy has arguably the most progressive early education system in the world, along with France (OECD 2001; Edwards et al. 1998; Corsaro and Emiliani 1992; New 1990). Two policies that contributed to major changes in Italian family life were those that supported parental leave and the establishment of pre-primary schools for children 3–6 years of age (New 1993). Today, the principle of universal access to services for families with young children enjoys wide political and public support. The commitment to establishing and maintaining high quality early childhood programs is clearly visible, and early childhood education is an educational arena where enthusiasm, initiative, autonomy, and sensitivity to local needs can be pursued (OECD 2001). Among the most noted educational philosophers who contributed to the establishment of quality early education was Bruno Ciari, who argued for communal oversight and management of all educational life and an active role for parents in most activities of the schools (Corsaro et al. 2002). Thus, the responsibility for the provision of high quality early care and education was placed into the arms of the surrounding community, the parents and families, and the school itself.

The Child Population and Evolution of Kindergarten

In Italy, the kindergarten population includes all children from 3 to 6 years of age. While this is true throughout the country, the northern region of Italy has made the greatest progress in establishing a quality and effective system of kindergarten settings that includes three types of funding support: state, municipal, and private (OECD 2001; New 1993). By the late 1970s, neighborhood councils were established, and their merger with municipal governments created a synergy that has resulted in the development of grassroots, progressive, innovative, and responsive forms of educational reform and school management. Today, nearly all kindergarten children from ages 3 to 6 years are actively engaged in the preschool or pre-primary education system.

Diversity and Early Education

While the size of the Italian population is relatively stable, qualitative changes are occurring that are both dramatic and subtle (OECD 2001). During the 1900s, Italy was a fairly homogenous society with an emphasis on intergenerational relationships and ancestry. Due to global economic unrest, an increasing number of immigrant families are settling in Italy. Over 1 million immigrants have settled in Italy in the past decade, with particularly high representation in the more industrial cities of northern Italy. In addition, internal migration has occurred since WWII as families moved from rural areas to the cities. These forces together have created demands on the kindergarten system of northern Italy. The numbers of children have increased and their needs are more complex due to language, cultural, and economic characteristics of their migrant families. Another trend in Italy is smaller families as women assume more active roles in the workforce. The birth rate has declined from 2.67 in 1965 to 1.19 in 1998 (OECD 2001, p. 12), and these demographic and societal trends are reflected in all three types of kindergartens in northern Italy.

Types of Kindergartens

There are three types of kindergartens; the private—typically operated by the Catholic Church—is the oldest. As early as 1869 policies were developed, advocating for preschools overseen by the king. For most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Catholic Church sponsored out-of-home care for disadvantaged children in the form of charitable social services, religious training, and family support (OECD 2001). The Italian family historically has viewed the role of caring for infants and toddlers as a family function. The desire to provide a system of quality care and education for preschool children began at the turn of the twentieth century. Maria Montessori’s establishment of her approach to working with young was in place in Rome by 1907 and later in Milan and other parts of the country (OECD 2001; Morrison 2009). But it was at the end of WWII that interest grew in creating systematic out of home experiences for 3 to 6 year old children. In the northern part of Italy the cities of Reggio Emilia, Modena, Bologna, and Parma were especially active in developing a system of kindergartens to serve this child population and especially children of working mothers. In 1968, the government passed Law 444 providing national funds for pre-primary schools and proclaiming the right of Italian children to pre-primary education (Edwards et al 1998; OCED 2001). This law marked a shift in perspective: Pre-primary education should be provided in response to children’s needs and rights rather than in response to maternal employment.This law also led to the establishment of a second and third type of kindergarten or scuola materna system: state and municipal. Thus, the oldest form of kindergarten is the privately run, followed by the state-run; the most contemporary type of kindergarten is the municipally operated.

Teacher Qualifications in the Kindergarten

The original state-run scuola maternafor 3 to 6 year old children had rather straightforward requirements for the teaching staff: young (less than 35 years old), and a vocational high school diploma from a specialized scuola magistrale (3 year secondary school) (OCED 2001). These teachers competed with others for a position in the state-run kindergartens; the selection process included examinations, evaluation of professional qualifications such as degrees or diplomas, and experience in working with young children or experimental projects. Criteria for the selection of preschool teachers were developed at the local level, and there was considerable variation from region to region in teacher selection criteria. In 1969, the Ministry of Education passed and then implemented a set of Guidelines for Educational Activity in the state-run scuola materna.An emphasis was placed on working with parents, religious education, and play. Thus a network of kindergarten settings grew and came under a more unified set of guidelines related to teacher qualifications, selection criteria, curriculum, and overall management. The state-run preschools provided meals free of charge and teachers’ salaries were paid by the state. State funds were also provided, in some cases, for the provision of free meals for children attending the newly emerging municipal as well as the private (primarily Catholic) preschool settings. Today, there is more homogeneity in teacher training and preparation for all kindergartens: Teachers are now required to have formal training in a pre-primary college preparation course.

Organizational Features Across Kindergarten Types

There are a number of important organizational features of the kindergarten system. One includes the policy of keeping the same group of about 20 children together for 3 years with the same two teachers (Corsaro et al. 2002). This practice is also observed in the 5 years of elementary school, and elementary schools are funded entirely by the national government. Thus, continuity is seen in building the relationships between the children and their teachers. In addition, most preschool settings include at least 3 different classrooms representing 3-, 4-, and 5-year olds. Therefore, the social context of the preschool experience is with same-aged or multi-aged peers but within a range of 3 through 5 years.

Contemporary northern Italy reflects these three types of kindergartens: state, municipal, and private. Funding sources for each of the kindergarten types vary, and new collaborative partnerships are developing, which reflect innovative and shared funding. In this section, the similarities and differences across types of kindergartens are described. The historical roots of early care and education in Italy, both pre- and post-WWII, bring together a shared philosophy and purpose for these educational settings for young children. A study of classroom environments using the global guidelines in the Emilia Romagna region

In this section, the authors describe the research study conducted in four towns in northern Italy in collaboration with other researchers from the USA and ACEI that resulted in the development of the Italian version of the GGA tool. Described here are the translation process of the ACEI Global Guidelines Assessment from English into Italian and then the participation of the kindergarten teachers in the pilot testing of the Italian GGA in kindergarten classrooms in Parma, Modena, Bologna, and Reggio Emilia, Italy.

Translation and Piloting of the GGA-IGA Tool

The following people have joined, in different times and with different roles, the Italian Consensus Group led by Luciano Cecconi: Francesca Corradi, Antonio Gariboldi, Giuseppe Malpeli, Andrea Pintus, Maria Alessandra Scalise.

The translation of the GGA into the GGA-IGA (Italian version) consisted of many phases that are now described. The first translation of the GGA tool into Italian was submitted for appraisal to an expert in kindergarten assessment tools. On the basis of the expert’s observations, a second draft was created. The second translation was submitted for appraisal to an expert in translation of educational texts. The consensus group, together with the first translator and the two experts, discussed and agreed on the text of the third translation.

The text of the third translation was presented to a group of 12 kindergarten educators—twice as many as initially planned—known as the review committee. This group of kindergarten teachers was asked to revise the text. The consensus group assigned the review committee the task of examining the GGA tool, from the viewpoint of educators who work in kindergartens on a daily basis and to formulate observations and suggestions, based on a structured worksheet designed by the consensus group.The consensus group examined and discussed the observations made by the review committee of kindergarten teachers. The fourth translation was prepared on the basis of the observations made by the review committee that the consensus group had accepted.

Pilot Study of the ACEI Global Guidelines Assessment in the Emilia Romagna Region

When the Italian version of the GGA was finalized, the next step was to pilot test the instrument in Italian early childhood classrooms. The pilot study consisted of several stages. First, the consensus group asked the review committee of kindergarten teachers if they would be willing to conduct the field test of the tool at their schools. Seven of the twelve members accepted the proposal, and they were joined by nine additional assessment participants for a total of sixteen assessment participants in the field test. The consensus group met with the group appointed to conduct the field test at the School of Education of the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in order to present the project goal; structure of the assessment tool; and procedure for applying the tool itself. After that meeting, two members of the consensus group were appointed to follow the participants throughout the period of field testing and to make themselves available to them whenever assistance was requested.

The field test was conducted in October 2008 involving eight kindergartens from the Emilia Romagna region for a total of sixteen classrooms: two from Bologna, one from Modena, three from Parma and two from Reggio Emilia. Of these eight schools, four are state schools, two are municipal schools and two are private schools. Sixteen assessment participants were involved, including nine educators, three school principals, two pedagogists, one form teacher, and one member of the auxiliary staff. Five of the participants have a university degree and the rest have a high school graduation certificate with a specific qualification for kindergarten education. In terms of length of service, the sixteen assessment participants had an average of 15.3 years’ work experience in kindergartens and an average of 5.5 years of working at the schools where they were actually conducting the assessment.

The consensus group examined the materials gathered during the field test (thirty two questionnaires) and designed the codification process for the open questions ‘Classroom Examples’ and ‘Comments’. The consensus group also prepared a worksheet to be used by the codifiers. The consensus group set up a laboratory of university students for encoding the open questions; the students were given appropriate training for the task. At this university laboratory, the students encoded the open questions and entered all the data relating to the other items in the Excel spread sheets prepared by the consensus group.The consensus group gathered all the data and forwarded to ACEI so that the data could be added to the ACEI-GGA database.

Reliability of the GGA-IGA Tool

In order to measure the reliability of the GGA-IGA tool, the group created a new dataset to calculate the average deviation between the assessments made by the rater pairs who assessed the same section within the various schools. The analysis reveals that the highest rater agreement was in two areas: Area 3 (early childhood educators and caregivers) and Area 5 (young children with special needs). The greatest disagreement was recorded in the other three areas: Area 1 (environment and physical space), Area 2 (curriculum content and pedagogy), and Area 4 (partnership with families and communities). This difference in level of agreement is essentially the same, both for the principal items and the parallel ones (‘Classroom Examples’, ‘Comments’).

If the same analysis is repeated in sub-categories, the results show that: The two subcategories with the highest rater agreement are ‘Common Philosophy and Common Aims’ and ‘Staff and Service Providers’. It is interesting to note that both of these subcategories belong to Area 5, thereby confirming the high degree of internal correlation in this area. Secondly, the two subcategories with the lowest rater agreement are “Learning Materials” and “Opportunities for Family and Community Participation”. In this case as well, it is interesting to note that the two sub-categories belonging to Areas 2 and 4 respectively show a rater agreement which is below the average. The three items that recorded the highest rater agreement (inter-rater reliability) and the three items with the lowest agreement were: item/area: highest agreement: 37/3, 58/4, 81/5 and lowest agreement: 15/1, 51/4, 61/4.

Recommendations to ACEI

On the basis of these observations, and in order to increase the use of the parallel items, the Italian group presented to ACEI two suggestions: (1) more time should be dedicated to training raters before administering the assessment tool in order to increase their motivation and provide them with a practical action guide for identifying and recording of examples; and (2) the procedure for administering the assessment tool should be revisited, for example, by attributing more importance to identifying and recording examples. If parallel items represent the peculiar characteristic of the assessment tool, then they should be allotted an adequate period of time for the procedure.

References

Corsaro, W., Molinari, L., & Rosari, K. (2002). Zena and Carlotta: Tran narratives and early education in the United States and Italy. Human Development, 45, 323–348.

Edwards, C., Gandini, L., & Forman, G. (1998). The hundred languages of children (2nd ed.). Westport: Ablex.

New, R. (1990). Excellent early education: A city in Italy has it. Young Children, 45(6), 4–10.

New, R. (1993). Reggio Emilia: Some lessons for U.S. educators. http://ceep.crc.uiuc.edu. Accessed 15 Aug. 2010.

OECD. (2001). Early childhood education and care policy in Italy. OECD Country Note, May 2001. Italy: Author.

Rinaldi, C. (2006). In dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, researching, and learning. London: Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group.

Stegelin, D. (2010). Personal observation. Reggio Emilia, Italy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Stegelin, D., Cecconi, L. (2013). Kindergarten Environments in Reggio Emilia, Bologna, Modena, and Parma, Italy In Search of Quality. In: Clark Wortham, S. (eds) Common Characteristics and Unique Qualities in Preschool Programs. Educating the Young Child, vol 5. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4972-6_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4972-6_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-4971-9

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-4972-6

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)