Abstract

The aim of the present study was to examine the relations of religiosity, worry, and perceived physical health state with various aspects of life satisfaction (i.e., emotional, social, and goal-related). The effects of individual differences factors (gender, age, and marital status) on life satisfaction were also explored. The sample consisted of 238 Greeks aged from 24 to 54 years. Results showed that participants were moderately to highly satisfied with their life and reported moderate levels of religious beliefs (e.g., belief in God) and low involvement in religious practices. They also reported moderate levels of worry and quite high perceived physical health state. Path analysis showed that personal/emotional life satisfaction was predicted by religious beliefs, general worry, and perceived health state; social life satisfaction was predicted by involvement in religious practices and worry, whereas goal-related life satisfaction was predicted by the two religiosity factors and absence of worry. General worry was predicted by religious beliefs, whereas involvement in religious practices predicted absence of worry. Overall, findings showed that religiosity influences life satisfaction both directly and indirectly through worry.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

Over the last decades, the association between psychological well-being and religiosity has acquired a renewed interest in psychological research and remains a complex and intriguing area for investigation. Religiosity has been operationalized in different ways in various studies. Most of these studies have found that religiosity is positively, albeit weakly, associated with subjective well-being (Kim-Prieto and Diener 2009; Powell et al. 2003). Nevertheless, research findings are often contradictory and appear to depend on the measures employed and the sample studied. Moreover, research on the association between religiosity and subjective well-being has been carried out with Protestant or Catholic Christian samples, while research concerning Greek Orthodox Christians is sparse.

The present study examined life satisfaction – a component of subjective well-being – and its relations with religiosity, worry, and perceived physical health state in a sample of Greek Orthodox Christian adults. Specifically, it examined the possible mediating role of worry and perceived physical health state in the relation between religiosity and life satisfaction. Also, it explored individual differences in relation to these measures. In what follows, I will first refer to conceptualizations of life satisfaction and religiosity as well as significant factors affecting them. Then, an empirical study will be presented that aimed to reveal the relation between different aspects of life satisfaction and religiosity and the mediating role of worry and perceived physical health state.

2 Life Satisfaction and Other Components of Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being refers to the subjective assessment of quality of life or, in other words, how people evaluate their lives. These evaluations can be both cognitive and affective and refer to life as a whole and/or to specific domains of it such as work or marriage (Diener et al. 1999). Subjective well-being involves a number of distinct components: life satisfaction (global judgments of one’s life), satisfaction with important life domains (e.g., work satisfaction), positive affect (experiencing pleasant emotions and moods), and low levels of negative affect (experiencing few unpleasant emotions and moods) (Diener 2000). Life satisfaction, in particular, is an overall assessment of feelings about, and attitudes toward, one’s life at a particular point in time and ranges from negative to positive; it comprises the desire to change one’s life, satisfaction with past achievements, optimism for the future, significant others’ perceptions of one’s life, etc. (Diener 1984).

Research on life satisfaction and related concepts is extensive, and theoretical debates over the nature and stability of life satisfaction continue. A common finding, though, is that most people report they are “somewhat” happy or/and satisfied with their lives even in face of great difficulties; in other words, they claim they are moderately to very satisfied with their lives and describe themselves as quite to very happy (Diener et al. 1999; Watson 2000). Yet, if life satisfaction differs among different domains of one’s life, then the question is whether the factors that affect life satisfaction have differential effects depending on the domain of one’s life involved. In this study, three aspects of life satisfaction were investigated: satisfaction with one’s personal/emotional and social life and satisfaction derived from attainment of one’s goals.

Subjective well-being also involves perceptions of physical and mental health and meaning in life (Diener & Ryan, 2009). Perceived (self-rated) health state is included in most of the subjective well-being measures (Kahneman and Krueger 2006). Health perceptions and subjective well-being are positively and significantly related (Okun et al. 1984). Moreover, high positive affect and low negative affect are beneficial to health and longevity (Diener and Chan 2011). This implies that, besides physical health, psychological or affective states, such as worry (negative affect) or lack of it, may contribute to different aspects of life satisfaction in different ways. Furthermore, affective factors, such as worry, should have an effect on perceptions of physical health.

Meaning in life is typically seen as a distinct component of subjective well-being, related more to what is called “psychological” or “eudaimonic” well-being than to hedonic or subjective well-being (Martos et al. 2010; Ryan and Deci 2001). Meaning in life reflects the subjective experience of meaningfulness or purpose in one’s life – something critical for human flourishing (Ryff and Singer 1998). There are also associations between meaning in life and a variety of health indicators, such as lower mortality rate (Boyle et al. 2009) and better self-rated physical health state (Steger et al. 2009). In this study, meaning in life was not directly assessed; rather the emphasis was on religiosity. Meaning in life, however, appears to be an important factor that links religiosity to mental health and well-being (George et al. 2002; Martos et al. 2010; Steger and Frazier 2005). The assumption was that religiosity, by providing meaning in life, would influence both people’s affective state (e.g., less worry) and life satisfaction.

3 Religiosity and Life Satisfaction

Religiosity presumably represents an important aspect of human personality (Unterrainer et al. 2010). It plays a significant role in how people construct their beliefs of what is important in life and shape the way they view the world, life, and self (Park 2005). In most of the studies, religiosity appears to have beneficial effects on subjective well-being, although the benefits vary among individuals (Pavot and Diener 2004). More specifically, as regards the relations between subjective well-being and religiosity, several studies have found that different indicators of subjective well-being, such as life satisfaction (Cohen et al. 2005a; Diener and Clifton 2002), subjective mental and physical health (Karademas 2010; Strawbridge et al. 2001), and experience of positive and negative emotions (Kim-Prieto and Diener 2009), are positively associated with religiosity dimensions, such as personal beliefs about God, devotion, participation in religious activities, and religious salience (the perceived importance of religion in one’s life) (Leondari and Gialamas 2009). In addition, it has been found that religiosity is positively associated with a reduced likelihood of anxiety disorders and depression (Koenig et al. 1993; Miller and Gur 2002). Moreover, religiosity has been found to have direct effects on health state and psychological well-being as well as indirect effects on well-being through health state (Levin and Chatters 1998).

Contrary to the evidence mentioned above, other studies showed that higher levels of religiosity are associated with higher personal distress (Dezutter et al. 2006; King and Schafer 1992). Furthermore, in a number of studies, no correlations were found between religiosity and measures of psychological well-being such as mental health, perceived physical health, loneliness, stress, or depression (Bergin 1991; Daaleman et al. 2004; Leondari and Gialamas 2009; O’Connor et al. 2003). It is also worth noting an apparently odd result found in a sample of Northern Irish students (Lewis et al. 1996). Although Irish youth is the most religious youth in Europe (followed by the Greek) (Vernadakis 2002), no evidence was found that individuals with a more positive attitude toward the Christian religion or a greater frequency of church attendance were more satisfied with their lives than the nonreligious groups.

As Emmons et al. (1998, p. 404) state, “one conclusion that is frequently drawn from the literature on well-being and religiosity is that the measures of religiousness employed and the components of well-being under examination matter. Indeed, depending upon the measures used, researchers can potentially document helpful, harmful, or no effects of religiousness on well-being”. Moreover, these relations may vary depending on gender and possibly on one’s religious denomination. For example, women were found to score higher in religiosity measures than men in Greek Orthodox Christians (Leondari and Gialamas 2009), and this is true for other denominations as well (Beit-Hallahmi and Argyle 1997; Diener and Clifton 2002).

Cohen et al. (2005b) pointed out that religiosity measures often focus either on religious involvement and behavior or on religious beliefs and attitudes. Cohen and his colleagues pinpoint that the most commonly used religiosity scales have been constructed for American Protestant denominations; because they are strongly related to individualism, Protestant denominations privilege private motivations for religion over social ones. However, certain religions, such as Christian Orthodoxy, Judaism, and Catholicism, are more collectivist in conception. They recognize social motivations and structural practices as being normative to the same degree as private, emotional motivations for religion. This suggests that the conceptualization of religiosity may differ across various cultures and traditions (de St. Aubin 1999).

3.1 Religiosity in Greece

Most of the empirical data on the association between religiosity and subjective well-being have been derived from Protestant or Catholic Christian samples. In the Greek Orthodox Christian context, only one study has been published recently on religiosity and subjective well-being (Leondari and Gialamas 2009). It was found that individuals who prayed more often reported being more anxious, while those attending church services more frequently expressed greater life satisfaction. To understand these findings, it is important to have the broader picture of the relations of Greek people with the Orthodox religion and the Orthodox Church. The Orthodox religion accounts for a strong share of the ethnic and cultural identity of Greek people (Stavrakakis 2002). Despite this, Leondari and Gialamas (2009) found that among 363 participants aged 18–48, the majority (97.2%) reported that they believed in a “personal” God or in an impersonal force and at the same time that religion was important or very important to them (about 78%). Many of the participants stated that they attended church only a few times a year (59.7%), and some of them never or rarely prayed (18%). In his review of religiosity of Greek people during the years 1963–1997 prepared for the Greek Helsinki Monitor, Demetras (n.d.) found similar to the above findings, that is, although Greeks declare high commitment to God and moderate commitment to Christian Orthodoxy, they admit low commitment to the Orthodox Church and religious practices. In a typology of Greeks according to their religiosity, 30% were classified as religious and frequent church attenders, 44% as religious but infrequent attenders, and 10% as religious but nonattenders. Based on the above, it seems that for Greek people religiosity in the sense of church attendance is not the same as belief in God or praying, and this may explain the findings of Leondari and Gialamas (2009).

To sum up, there are two aspects of religiosity, belief in God and participation in religious practices. In Greeks, these two aspects of religiosity seem not to be highly associated. Therefore, it is important to know which aspect of religiosity is related to life satisfaction and specifically to satisfaction with one’s personal/emotional life, social life, and satisfaction from attainment of one’s goal.

4 Aims and Hypotheses of the Study

The present study aimed at investigating the relationships between different dimensions of life satisfaction and the two main aspects of religiosity, worry – as indicator of mental health – and perceived physical health state. According to the empirical evidence reviewed earlier, life satisfaction was expected to be positively related to religiosity (hypothesis 1) and perceived physical health state (hypothesis 2) and negatively related to worry (hypothesis 3) (Cohen et al. 2005a; Diener 2000; Diener and Clifton 2002; Levin and Chatters 1998). Specifically, belief in God was hypothesized to predict satisfaction with personal/emotional and with goal-related life, while participation in religious activities was hypothesized to predict satisfaction with social life (hypothesis 4) (Cohen et al. 2005a; Diener and Clifton 2002; Leondari and Gialamas 2009; Levin and Chatters 1998). Perceived physical health state was assumed to predict personal/emotional life satisfaction (hypothesis 5) (Karademas 2010; Strawbridge et al. 2001). Finally, worry was hypothesized to predict life satisfaction dimensions (hypothesis 6), since earlier research showed that related traits, such as neuroticism and anxiety, influence positive affect or satisfaction (Costa and McCrae 1980; Paolini et al. 2006). In addition to the above, the model hypothesized that the two religiosity aspects (beliefs and participation) would also predict worry (hypothesis 7). Previous research has shown that anxiety, depression, and distress are related to religiosity, positively (Dezutter et al. 2006; King and Schafer 1992) or negatively (Koenig et al. 1993; Miller and Gur 2002); this implies that religiosity has both a direct and an indirect (via worry) effect on life satisfaction.

5 Method

5.1 Participants

In this study, 238 young and middle-aged Greeks participated on a voluntary basis; 95 (40%) were males and 143 (60%) females. Their age ranged from 24 to 54 years, with a mean of 33.1 years (SD = 6.3). Regarding marital status, 148 (62%) reported being married or had a romantic relationship and 90 (38%) were single, divorced, or widowed. Their educational level was quite high, as 57.3% of the participants held a university or master’s degree and 31.3% were either junior high or high school graduates. Participants were approached at various places and asked to voluntarily participate in the study.

5.2 Instruments

Participants were asked to complete a set of self-report questionnaires which were designed for the purpose of the present study based on other relevant scales: the Life Satisfaction Scale and the Religiosity Scale. In addition, the Penn State Worry Questionnaire was administered along with questions on their perceived physical health state.

Life Satisfaction Scale was based on existent scales, such as the Life Satisfaction Inventory (Neugarten et al. 1961) and the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985). The questionnaire consists of 14 items (see Table 6.1). It assesses how satisfied participants are with various aspects of their life. Participants responded to each item on a five-point scale (1 to 5), with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

Exploratory factor analysis using varimax rotation was applied on the 14 items of the scale, and a three-factor solution was produced accounting for 64.18% of the total variance (see Table 6.1). One item (L8) loaded almost equally on two factors, so it was removed from further analyses. The first factor refers to personal/emotional satisfaction with one’s life (7 items, Cronbach’s α = .87), the second refers to satisfaction with one’s social life (4 items, Cronbach’s α = .80), and the third refers to goal-related life satisfaction focusing on goal pursuit and attainment (2 items, Cronbach’s α = .78). As Cronbach’s alphas indicate, internal consistencies of the three life satisfaction factors were quite satisfactory.

Religiosity Scale. For the needs of the present study, the Religiosity Scale was built based on prior scales such as the Religious Orientation Scale (Allport and Ross 1967). The scale consists of 20 self-report statements (see Table 6.2); participants were asked to rate how strongly they hold various beliefs (e.g., I believe that powers of Good and Evil exist) or how frequently they practice religious behaviors (e.g., I take confession) on a five-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater frequency (or strength) of the particular experience, feeling, or belief.

Exploratory factor analysis using varimax rotation was applied on the 20 items of the scale. Two factors were abstracted accounting for 63.7% of the total variance (see Table 6.2). Two items (R1 and R7) were found to load almost equally on the two factors, so they were excluded from further analyses. The first factor taps belief in God (13 items, Cronbach’s α = .95); the second factor taps involvement in religious practices (5 items, Cronbach’s α = .86). As Cronbach’s alphas indicate, internal consistency of the two religiosity factors was very satisfactory.

Penn State Worry Questionnaire. The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (Meyer et al. 1990) was developed to assess worry as a trait and has proven to be a reliable and valid measure in a number of studies (Beck et al. 1995; Brown et al. 1992). In this study, the Greek version of the questionnaire, as translated and adjusted by Simos et al. (1998), was used to assess the two dimensions of worry: general worry and not-worry. Participants were presented with 16 statements and asked to rate them on a scale of 1 (“not at all typical of me”) to 5 (“very typical of me”). Items are presented in Table 6.3.

As with the previous scales, an exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation was applied on the 16 items of the questionnaire to check for its structure. Two factors were abstracted (accounting for 62.2% of the total variance) that assess two dimensions of worry: general worry (11 items, Cronbach’s α = .96) and not-worry or absence of worry (5 items, Cronbach’s α = .61). The two-factor solution (presented in Table 6.3) is fully consistent with the original design of the questionnaire (Meyer et al. 1990).

Perceived Physical Health State. In addition to the above measures, participants rated their physical and psychosomatic heath on a three-item scale. They were asked to rate on a five-point scale (1 = ”very poor” or “not at all” to 5 = ”excellent” or “all the time”) the severity of the physical health problems they experienced in the last 2 years, the frequency of their psychosomatic symptoms, and the state of their general health during the last 6 months. The mean of the three items was used as indicator of participants’ perceived physical health state, with higher scores indicating better self-rated health state. Reliability of this scale was rather low (Cronbach’s α = .58).

6 Results

6.1 Individual Differences Effects

6.1.1 Life Satisfaction

The mean scores of the items loading on the three factors showed that participants were moderately to highly satisfied with the goal-related aspect of their life (M = 3.8 SD = 0.83), followed by satisfaction with personal/emotional life (M = 3.53 SD = 0.71) and satisfaction with social life (M = 3.42 SD = 0.81). A series of ANOVAs showed no significant effects of gender or marital status, except for one case, F(1, 235) = 10.84, p < .001, partial η 2 = .04: married participants or those in a romantic relationship reported higher scores in personal/emotional life satisfaction (M = 3.65 SD = 0.66) than the single, divorced, or widowed ones (M = 3.34 SD = 0.77). Finally, age was not significantly related with any of the life satisfaction factors.

6.1.2 Religiosity

The means of the items loading each of the two factors suggest that participants reported moderate levels of belief in God (M = 3.24 SD = 1.09) and low involvement in religious practices (M = 1.76 SD = 0.71). ANOVA showed a gender effect only in relation to belief in God, F(1, 236) = 9. 43, p < .05, partial η 2 = .04, with women reporting higher levels of belief (M = 3.41 SD = 1.03) than men (M = 2.99 SD = 1.06). No significant differences between genders were found in involvement in religious practices. Marital status had no effect on the two religiosity factors. Finally, age did not have any significant association with either factor.

6.1.3 Worry

The mean scores of the items loading on the two factors of the Penn State Worry questionnaire suggest that participants reported moderate levels of both general worry (M = 2.8 SD = 0.95) and not-worry or absence of worry (M = 2.52 SD = 0.65). ANOVA showed that women (M = 2.99 SD = 1) scored significantly higher than men (M = 2.52 SD = 0.8) only in the general worry factor, F(1, 236) = 14.54, p < .001, partial η 2 = .06. No significant effects of marital status were found and no significant correlation with age.

6.1.4 Perceived Physical Health State

In general, participants were quite satisfied with their physical heath state (M = 4.06 SD = 0.67), with men (M = 4.23 SD = 0.61) reporting significantly higher scores than women (M = 3.95 SD = 0.68), F(1, 234) = 10.42, p < .01, partial η 2 = .04. Marital status and age did not affect participants’ perceived physical health state.

7 Relations Between Life Satisfaction, Religiosity, Worry, and Perceived Health State

To investigate the relations between the measures of life satisfaction, religiosity, worry, and perceived health state, correlations were firstly computed. As Table 6.4 suggests, the personal/emotional and the social (but not the goal-related) life satisfaction correlated significantly with almost all other variables. Specifically, hypothesis 1 was partially confirmed as both of the religiosity factors correlated significantly with personal/emotional life satisfaction (involvement in religious practices correlated also with social life satisfaction), and neither of them correlated with goal-related life satisfaction. All three life satisfaction dimensions correlated positively with perceived health state, as hypothesis 2 assumed. Also, they negatively correlated with the worry and the not-worry factors, as hypothesis 3 predicted, with one exception: goal-related life satisfaction correlated only with the not-worry factor. Finally, belief in God positively correlated with general worry, whereas involvement in religious practices negatively correlated with not-worry.

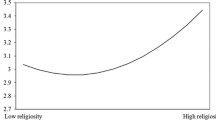

7.1 Predictors of Life Satisfaction

To examine whether life satisfaction was predicted by the religiosity factors, worry, and perceived physical health state, path analysis was applied using the EQSWIN version 6.1 (Bentler 2005). The maximum likelihood robust method of estimation was used. The Satorra-Bentler Scaled χ 2 (123) = 226.92, p < .001 was significant. Given the sensitivity of χ 2 to sample size (Byrne 2006), model fit assessment was based mainly on the remaining goodness-of-fit-indicators provided in the analysis. Specifically, the ratio χ 2/df = 1.79, CFI = .930, NNFI = .911, and RMSEA = .058 (CI90%.045–070) indicated a relatively good model fit (Schreiber et al. 2006). The model tested is presented in Fig. 6.1.

In this model, the direct paths running from religiosity factors, worry factors, and perceived health state to the life satisfaction dimensions were significant. This confirmed the respective hypotheses. Specifically, as regards the effects of the religiosity factors on life satisfaction dimensions (hypothesis 4), personal/emotional and goal-related life satisfaction were positively predicted by belief in God; social life satisfaction was positively predicted by involvement in religious practices; unexpectedly, goal-related life satisfaction was negatively predicted by involvement in religious practices.

Perceived physical health state positively predicted personal/emotional life satisfaction, as hypothesis 5 suggested. Personal/emotional and social life satisfaction dimensions were also predicted (negatively) by the two worry factors, while goal-related life satisfaction was predicted only by not-worry (hypothesis 6). The effects were negative suggesting that excessive worry is as detrimental to goal-related life satisfaction as absence of worry. Finally, two negative paths were found connecting religiosity with worry; the first connected belief in God with general worry and the second involvement in religious practices with not-worry. This finding confirms hypothesis 7 and suggests that religiosity dimensions have both a direct and an indirect effect (through worry) on life satisfaction dimensions.

8 Discussion

In this study, we investigated life satisfaction in relation to religiosity, worry, and perceived physical health state of a Greek sample.

8.1 Life Satisfaction

As Pavot and Diener (2003) suggest, it is usually advantageous to assess each component of a construct (e.g., life satisfaction) separately, with specifically constructed measures that accurately tap each component. In this way, assessment of each component is more precise, distinctions between components are attained more easily, and potentially unique relations between components and other variables are likely to be revealed.

In this study, the Life Satisfaction Scale was used to provide measures of three distinct dimensions of life satisfaction: personal/emotional life satisfaction, satisfaction with one’s social life, and goal-related life satisfaction. Mean scores indicated that, in agreement to relevant research, Greeks are quite satisfied with their lives. As most studies have shown, people report moderate to high satisfaction with their lives (Diener et al. 1999), even in the face of hardships (Folkman 1997).

Among the individual differences factors studied, gender and age did not have any effect on the reported life satisfaction of the Greeks; married or participants in romantic relationship reported higher personal/emotional life satisfaction than the single ones. These results are in line with the majority of prior empirical evidence regarding Greeks (Efklides et al. 2003; Karademas and Kalantzi-Azizi 2005) or non-Greek samples (Joshi 2010; Kelleher et al. 2003; Ryan and Deci 2001). As Pavot and Diener (2004) put it in their literature review, the average levels of life satisfaction are relatively similar for groups representing early, middle, and late adulthood.

Regarding marital status, a positive relationship of life satisfaction with marital status is a common finding in studies all over the world (Diener and Ryan 2009). Married or people in romantic relationships are more satisfied with various aspects of their lives compared to unmarried, divorced, or widowed ones. However, there is no consensus on the interpretation of this finding: is it because family acts as a protective factor against vicissitudes (Coombs et al. 1991) or because the happier and better-adjusted individuals are those who opt to get and stay married (Stutzer and Frey 2006; Veenhoven 1989)? Obviously, there is need for more research on this issue.

8.2 Religiosity

Two aspects of religiosity were measured, namely, belief in God and involvement in religious practices. Greek participants reported moderate levels of belief in God (or in an impersonal force) but quite low involvement in religious practices, such as church going, taking confession, and fasting. Leondari and Gialamas (2009) and Demetras (n.d.) have also found a relatively low frequency of church attendance and prayer in their samples. The present study confirms the above findings suggesting that, despite their self-reported religious identity, Greeks are not very active members of the Greek Orthodox Church.

8.3 Worry

The participants of our study reported moderate levels of both general worry and absence of worry. Women reported a little higher level of general worry than men, a common finding in the literature (Robichaud et al. 2003; Zalta and Chambless 2008). No effects of marital status or correlations with age were noted. Regarding age, in particular, relevant evidence suggests that worry proneness is reduced in late adulthood; a greater ability to tolerate uncertainty in life and to see less value in worrying may partially account for this finding (Basevitz et al. 2008). In the current study, however, the age of participants ranged only from early to middle adulthood (elderly participants were not included), a fact which may explain the lack of significant age differences.

8.4 Perceived Physical Health State

Finally, perceived physical health state of the participants was assessed. Participants’ perception of their physical health was quite high, especially that of males. Consistent to previous findings, women reported more physical and psychosomatic symptoms than men (Neupert et al. 2007). However, there were no effects of marital status or age on reported physical health state.

9 Predictors of Life Satisfaction

Path analysis revealed a distinct pattern of predictors of each life satisfaction dimension. Specifically, personal/emotional life satisfaction was positively predicted by belief in God and perceived heath state and negatively by general worry; social life satisfaction was positively predicted by involvement in religious practices and negatively by general worry and absence of worry; goal-related life satisfaction was positively predicted by belief in God and negatively by involvement in religious practices. It was also negatively predicted by absence of worry.

9.1 Life Satisfaction and Religiosity

The study showed that personal/emotional life satisfaction was positively related to belief in God and directly predicted by it. This finding suggests that the more religious people, in terms of faith to God, tend to report higher levels of personal/emotional life satisfaction. Many empirical studies have shown that religious people are on average more satisfied with their life (Diener and Clifton 2002; Diener and Seligman 2004), possibly because faith provides them with a sense of meaning and purpose in life (Pollner 1989).

However, regarding the social life satisfaction, faith did not have any effect. On the contrary, involvement in religious practices positively predicted social life satisfaction, probably because church services and activities offer a sense of being member of a community of people who share values and meaning in life. As relevant findings suggest, participation in religious services, strength of religious affiliation, relationship with God, and prayer have all been associated with higher well-being levels (Ferriss 2002; Poloma and Pendleton 1990; Witter et al. 1985). The positive link between well-being and religiosity is thought to originate from a sense of meaning and purpose and from the social networks and support systems created by churches and other institutions of organized religion (Diener and Ryan 2009).

Path analysis also showed that belief in God positively predicted goal-related life satisfaction, whereas involvement in religious practices negatively predicted it. Following Witter et al. (1985), belief in God may contribute to personal/emotional life satisfaction as well as to the goal-related aspect of life satisfaction by helping people successfully resolve the issue of ego integrity versus despair (Erikson 1959, 1975). This is particularly true as regards goal attainment, since religious people believe that God is helping them in times of difficulty and gain strength from their belief so as to resolve problems and attain their goals. The negative effect of involvement in religious practices on goal-related life satisfaction is hard to explain. It is likely that Greek people believe that active participation in church activities can be an obstacle to achieving one’s broader goals in life, possibly because church imposes constrains on behavior and promotes a particular lifestyle, which is shared by those who frequently attend church activities.

Such an explanation is consistent with the findings that Greek people report high belief in God but do not attend religious activities much.

9.2 Life Satisfaction in Relation to Worry and Perceived Health State

The study showed that both general worry and lack of worry were negatively related to life satisfaction. This is probably due to the fact that worrying about everything all the time does not allow the person to enjoy life and feel happy and adversely affects social relationships. “Not worrying,” on the other hand, represents a kind of avoidance of worry (see Table 6.3 for the items of the scale), which is also a negative emotional state; “not worrying” does not mean that the individual is in a positive affective state, particularly in face of difficulties when worrying would be adaptive for goal attainment. Thus, individuals who experience lower general worry tend to be more satisfied with their personal/emotional and social lives. Those reporting higher lack of worry, on the other hand, also report less satisfaction with their personal/emotional and their social lives and with their goal-related life as well. This may mean that life satisfaction makes sense when one overcomes difficulties and attains one’s goals. Being in a state of continuous lack of challenges (by avoiding them) or worries deprives the person of the sense of personal worth and achievement. These findings are in agreement with prior evidence. For example, in a sample of college students, those scoring higher on worry experienced significantly less life satisfaction than those scoring lower, even after controlling for anxiety (Paolini et al. 2006). This suggests that worry as a trait is a strong predictor of life satisfaction that pervades various dimensions of life satisfaction; additionally, it confirms earlier research which showed that traits such as neuroticism and anxiety influence positive affect or satisfaction (Costa and McCrae 1980; Paolini et al. 2006).

Unlike worry, higher life satisfaction was related to higher perceived physical health state. Perceived health state and life satisfaction are usually intercorrelated, but they often show differential relations with other variables (Pavot and Diener 2004). Thus, in the path model, perceived health state predicted only personal/emotional life satisfaction, while the residuals of this variable correlated significantly with the other two dimensions of life satisfaction. These findings indicate the differential effect of perceived health state in people’s evaluation of their life. Specifically, perceived physical health state is significant for personal/emotional life satisfaction but not for satisfaction with social life and the goal pursuit aspect of life. Moreover, perceived physical health mediated the effect of general worry on personal/emotional life satisfaction. Perceived physical health state was negatively related to general worry. It seems that physical health is something people often worry about. The less one worries about one’s health, the more satisfied one is with emotional/personal life. Therefore, worry had both a direct, negative effect on emotional/personal life satisfaction and an indirect effect via more positive perceptions of physical health.

9.3 Religiosity and Worry

So far, our discussion regarded the paths from the religiosity and the worry factors to the life satisfaction dimensions. However, religiosity also affected worry. Previous research has shown that anxiety, depression, and distress are related to religiosity (Dezutter et al. 2006; King and Schafer 1992). For example, in the Leondari and Gialamas study (2009), people who reported praying more were found to be more anxious than nonprayers. Probably this is due to the fact that stressful life events (such as chronic pain) prompt individuals to be involved in prayer and religion, as a means of coping with their distress. In this study, belief in God was negatively related to general worry, which means that people feel strengthened and worry less in times of distress. Involvement in religious practices was negatively related to not-worry, but it was not related to general worry. This suggests that involvement in religious activities is making people more aware of difficulties in life and less avoidant of worrying. Involvement in religious practices, however, did not increase general worry. Thus, belief in God reassures the person and decreases worry, and involvement in religious practices lowers the level of not-worry.

Both of these functions of religiosity are positive and indirectly contribute to life satisfaction. Overall, the findings of the present study suggest that religiosity influences life satisfaction both directly and indirectly through worry. Obviously, more research is required to confirm the above findings and delineate the mediating role of worry in the relationship between religiosity and life satisfaction in Greek vis-à-vis non-Greek samples.

10 Limitations of the Study and Future Research

The findings of this study capture Greek people’s life satisfaction at a time before the recent financial crisis in Greece. Thus, they can be useful as baseline measures for future research. Specifically, since data collection, Greece has been going through a major financial crisis which is expected to impact subjective well-being of the Greek people. Taken the results of Realo and Dobewall (2011) into consideration, who found that life satisfaction varies as a function of the interaction of cohort and historical period, it would be interesting to investigate the extent to which life satisfaction of Greeks (and its relation to religiosity and age) will change as a result of the dramatic political and financial developments in the country.

These findings should, however, be considered with caution as this study has certain limitations. Religiosity is a complex experience embedded in culture, which is inextricable from personal well-being and lifestyle (Karademas and Petrakis 2009). Thus, the examination of limited aspects of religiosity (such as belief in God and involvement in religious practices) and their relation to life satisfaction may be insufficient. Moreover, this is a cross-sectional study, based on self-report data. Future empirical studies should also include older participants and further investigate worry or relevant traits as mediating factors in determining the valence and direction of the links between religiosity and life satisfaction.

References

Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 432–433.

Basevitz, P., Pushkar, D., Chaikelson, J., Conway, M., & Dalton, C. (2008). Age-related differences in worry and related processes. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 66(4), 283–305.

Beck, J. G., Stanley, M. A., & Zebb, B. J. (1995). Psychometric properties of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire in older adults. Journal of Clinical Gerontology, 1, 33–42.

Beit-Hallahmi, B., & Argyle, M. (1997). The psychology of religious behaviour, belief and experience. London: Routledge.

Bentler, P. M. (2005). EQS 6.1. Encino: Multivariate Software.

Bergin, A. E. (1991). Values and religious issues in psychotherapy and mental health. American Psychologist, 46, 394–403.

Boyle, P. A., Barnes, L. L., Buchman, A. S., & Bennett, D. A. (2009). Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(5), 574–579.

Brown, T. A., Antony, M. M., & Barlow, D. H. (1992). Psychometric properties of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire in a clinical anxiety-disorders sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 30, 33–37.

Byrne, B. M. (2006). Structural equation modeling with EQS: Basic concepts, applications and programming (2nd ed.). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Cohen, A. B., Pierce, J. D., Jr., Chambers, J., Meade, R., Gorvine, B. J., & Koenig, H. G. (2005a). Intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity, belief in the afterlife, death anxiety, and life satisfaction in young Catholics and Protestants. Journal of Research in Personality, 39, 307–324.

Cohen, A. B., Hall, D. E., Koenig, H. G., & Meador, K. (2005b). Social versus individual motivation: Implications for normative definitions of religious orientation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9, 48–61.

Coombs, R. H., Paulson, M. J., & Richardson, M. A. (1991). Peer versus parental influence in substance use among Hispanic and Anglo children and adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20, 3–88.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Still stable after all these years: Personality as a key to some issues in adulthood and old age. In P. B. Baltes, & O. G. Brim, Jr. (Eds.), Life span development and behavior (Vol. 3. pp. 65–102). New York: Academic Press.

Daaleman, T. P., Perera, S., & Studenski, S. A. (2004). Religion, spirituality, and health status in geriatric outpatients. Annals of Family Medicine, 2, 49–53.

Demetras, P. I. (n.d.). Religiosity of the Greeks: A longitudinal approach (1963–1997). Accessed from http://www.greekhelsinki.gr/pdf/religion.PDF

de St. Aubin, E. (1999). Personal ideology: The intersection of personality and religious beliefs. Journal of Personality, 67, 1105–1139.

Dezutter, J., Soenens, B., & Hutsebaut, D. (2006). Religiosity and mental health: A further exploration of the relative importance of religious behaviors versus religious attitudes. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 807–818.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness, and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34–43.

Diener, E., & Chan, M. Y. (2011). Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 3(1), 1–43.

Diener, E., & Clifton, D. (2002). Life satisfaction and religiosity in broad probability samples. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 206–209.

Diener, E., & Ryan, K. (2009). Subjective well-being: A general overview. South African Journal of Psychology, 39, 391–406.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5, 1–31.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Efklides, A., Kalaitzidou, M., & Chankin, G. (2003). Subjective quality of life in old age in Greece: The effect of demographic factors, emotional state, and adaptation to aging. European Psychologist, 8, 178–191.

Emmons, R. A., Cheung, C., & Tehrani, K. (1998). Assessing spirituality through personal goals: Implications for research on religion and subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 45, 391–422.

Erikson, E. H. (1959). Late adolescence. In D. H. Funkenstein (Ed.), The student and mental health (pp. 66–106). Cambridge: Riverside Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1975). Life history and the historical moment. New York: Norton.

Ferriss, A. (2002). Religion and the quality of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(3), 199–215.

Folkman, S. (1997). Using bereavement narratives to predict well-being in gay men whose partners died of AIDS: Four theoretical perspectives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 851–854.

George, L. K., Ellison, C. G., & Larson, D. B. (2002). Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 190–200.

Joshi, U. (2010). Subjective well-being by gender. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 1(1), 20–26.

Kahneman, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20, 3–24.

Karademas, E. C. (2010). Illness cognitions as a pathway between religiousness and subjective health in chronic cardiac patients. Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 239–247.

Karademas, E. C., & Kalantzi-Azizi, A. (2005). Subjective well-being, demographic and interpersonal variables. Psychology, 12, 506–523 (in Greek).

Karademas, E. C., & Petrakis, C. (2009). The relation of intrinsic religiousness to the subjective health of Greek medical inpatients: The mediating role of illness-related coping. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 14, 466–475.

Kelleher, C. C., Friel, S., Nic Gabhainn, S., & Tay, J. B. (2003). Socio-demographic predictors of self-rated health in the Republic of Ireland: Findings from the National Survey on Lifestyle, Attitudes and Nutrition, SLAN. Social Science and Medicine, 57, 477–486.

Kim-Prieto, C., & Diener, E. (2009). Religion as a source of variation in the experience of positive and negative emotions. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 447–460.

King, M., & Schafer, W. E. (1992). Religiosity and perceived stress: A community survey. Sociological Analysis, 53, 37–47.

Koenig, H. G., Ford, S., George, L. K., Blazer, D. G., & Meador, K. G. (1993). Religion and anxiety disorder: An examination and comparison of associations in young, middle-aged and elderly adults. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 7, 321–342.

Leondari, A., & Gialamas, V. (2009). Religiosity and psychological well-being. International Journal of Psychology, 44(4), 241–248.

Levin, J. S., & Chatters, L. M. (1998). Research on religion and mental health: An overview of empirical findings and theoretical issues. In H. G. Koenig (Ed.), Handbook of religion and mental health (pp. 33–50). San Diego: Academic.

Lewis, C. A., Joseph, S., & Noble, K. E. (1996). Is religiosity associated with life satisfaction? Psychological Reports, 79, 429–430.

Martos, T., Konkoly Thege, B., & Steger, M. F. (2010). It’s not only what you hold, it is how you hold it: Dimensions of religiosity and meaning in life. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 863–888.

Meyer, T. J., Miller, M. L., Metzger, R. L., & Borkovec, T. D. (1990). Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28, 487–495.

Miller, L., & Gur, M. (2002). Religiosity, depression, and physical maturation in adolescent girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 206–214.

Neugarten, B. L., Havighurst, R. J., & Tobin, S. S. (1961). The measurement of life satisfaction. Journal of Gerontology, 16, 134–143.

Neupert, S. D., Almeide, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (2007). Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: The role of personal control. Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological and Behavioral Sciences, 62, 216–225.

O’Connor, D. B., Cobb, J., & O’Connor, R. C. (2003). Religiosity, stress and psychological distress: No evidence for an association among undergraduate students. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 211–217.

Okun, M. A., Stock, W. A., Haring, M. J., & Witter, R. A. (1984). Health and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 19, 111–132.

Paolini, L., Yanez, A. P., & Kelly, W. E. (2006). An examination of worry and life satisfaction among college students. Individual Differences Research, 4(5), 331–339.

Park, C. L. (2005). Religion as a meaning-making framework in coping with life stress. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 707–729.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2003). The assessment of subjective well-being. In R. F. Ballesteros (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychological assessment (Vol. 2, pp. 1097–1101). London: Sage.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2004). The subjective evaluation of well-being in adulthood: Findings and implications. Ageing International, 29(2), 113–135.

Pollner, M. (1989). Divine relations, social relations, and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30, 92–104.

Poloma, M., & Pendleton, B. F. (1990). Religious domains and general well-being. Social Indicators Research, 22, 255–276.

Powell, L. H., Shahabi, L., & Thoresen, C. E. (2003). Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist, 58, 36–52.

Realo, A., & Dobewall, H. (2011). Does life satisfaction change with age? A comparison of Estonia, Finland, Latvia, and Sweden. Journal of Research in Personality, 45, 297–308.

Robichaud, M., Dugas, M. J., & Conway, M. (2003). Gender differences in worry and associated cognitive-behavioral variables. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 17(5), 501–516.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (1998). The role of purpose in life and personal growth in positive human functioning. In P. T. P. Wong & P. S. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 213–235). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–337.

Simos, G., Vaiopoulos, C., Dimitriou, E., & Giouzepas, I. (1998). Worries and obsessive features: A positive relationship. The Behavior Therapist, 21(1), 7–9.

Stavrakakis, Y. (2002). Religion and populism: Reflections on the “politicized” discourse of the Greek Orthodox Church (Hellenic Observatory, Discussion Paper No. 7). London: The European Institute, the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Steger, M. F., & Frazier, P. (2005). Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 574–582.

Steger, M. F., Mann, J. R., Michels, P., & Cooper, T. C. (2009). Meaning in life, anxiety, depression, and general health among smoking cessation patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 67, 353–358.

Strawbridge, W. J., Shema, S. J., Cohen, R. D., & Kaplan, G. A. (2001). Religious attendance increases survival by improving and maintaining good health behaviors, mental health and social relationships. Annual Behavioral Medicine, 23, 68–74.

Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. S. (2006). Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35, 326–347.

Unterrainer, H. F., Ladenhauf, K. H., Moazedi, M. L., Wallner-Liebmann, S. J., & Fink, A. (2010). Dimensions of religious/spiritual well-being and their relation to personality and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(3), 192–197.

Veenhoven, R. (1989). Does happiness bind? Marriage chances of the unhappy. In R. Veenhoven & A. Hagenaars (Eds.), How harmful is happiness? Consequences of enjoying life or not (pp. 44–60). Rotterdam: Universitaire Pers.

Vernadakis, C. (2002). The public opinion in Greece—VPRC investigations-surveys. Athens: Livanis.

Watson, D. (2000). Mood and temperament. New York: The Guilford Press.

Witter, R. A., Stock, W. A., Okun, M. A., & Haring, M. J. (1985). Religion and subjective well-being in adulthood: A quantitative synthesis. Review of Religious Research, 26, 332–342.

Zalta, A. K., & Chambless, D. L. (2008). Exploring sex differences in worry with a cognitive vulnerability model. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(4), 469–482.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Platsidou, M. (2012). Life Satisfaction in Adults: The Effect of Religiosity, Worry, and Perceived Physical Health State. In: Efklides, A., Moraitou, D. (eds) A Positive Psychology Perspective on Quality of Life. Social Indicators Research Series, vol 51. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4963-4_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4963-4_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-4962-7

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-4963-4

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)