Abstract

This paper addresses a significant gap in the conceptualization of business ethics within different cultural influences. Though theoretical models of business ethics have recognized the importance of culture in ethical decision-making, few have examined how this influences ethical decision-making. Therefore, this paper develops propositions concerning the influence of various cultural dimensions on ethical decision-making using Hofstede’s typology.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Over the last decade, the topic of social responsibility and ethics in business has been of significant interest to scholars. However, few studies have been cross-cultural in content, even though existing theoretical models recognize the importance of this factor (e.g., Ferrell and Gresham 1985; Hunt and Vitell 1986, 1992). Bartels (1967) was one of the first to note the importance of the role of culture in ethics decision-making identifying cultural factors such as values and customs, religion, law, respect for individuality, national identity and loyalty (or patriotism), and rights of property as influencing ethics. In their general theory of marketing ethics, Hunt and Vitell (1986, 1992) incorporated cultural norms as one of the constructs that affect one’s perceptions in ethical situations. The influence of cultural and group norms/values on individual behavior was also noted by Ferrell and Gresham (1985) in their contingency framework for understanding ethical decision making within a business context. However, neither these theoretical conceptualizations of ethical decision-making nor subsequent empirical investigations tell us how culture influences ethics and ethical decision-making.

In the present paper, the authors provide a conceptual framework as to how culture influences one’s perceptions and ethical decision-making in business. In order to accomplish this task, the authors have adopted the cultural typology proposed by Hofstede (1979, 1980, 1983, 1984) regarding the differences between countries based on certain cultural dimensions. With respect to business ethics, the authors have adopted the revised model proposed by Hunt and Vitell (1992). Our overall objective is to develop research propositions that involve the relationship between the cultural component and other elements of decision-making in situations involving ethical issues.

The Cultural Typology

Hofstede argues that societies differ along four major cultural dimensions: power distance, individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance. This cultural typology is based on the findings of several studies (i.e., Hofstede 1979, 1980, 1983, 1984). According to Hofstede (1984), power distance is the extent to which the less powerful individuals in a society accept inequality in power and consider it as normal. Although inequality exists within every culture, the degree to which it is accepted varies from culture to culture. Hofstede defines individualist cultures as being those societies where individuals are primarily concerned with their own interests and the interests of their immediate family. Collectivist cultures, in contrast, assume that individuals belong to one or more “in-groups” (e.g., extended family, clan, or other organization) from which they cannot detach themselves. The “in-group” protects the interest of its members, and in turn expects their permanent loyalty.

Masculinity, according to Hofstede, is the extent to which individuals in a society expect men (as opposed to women) to be assertive, ambitious, competitive, to strive for material success, and to respect whatever is big, strong and fast. Masculine cultures expect women to serve and to care for the non-material quality of life, for children, and for the weak. Feminine cultures, on the other hand, define relatively overlapping social roles for both sexes with neither men nor women needing to be overly ambitious or competitive. Masculine cultures value material success and assertiveness while feminine cultures value qualities such as interpersonal relationships and concern for the weak.

Uncertainty avoidance is defined as the extent to which individuals within a culture are made nervous by situations that are unstructured, unclear, or unpredictable, and the extent to which these individuals attempt to avoid such situations by adopting strict codes of behavior and a belief in absolute truth. Cultures with strong uncertainty avoidance are active, aggressive, emotional, security-seeking, and intolerant. On the other hand, cultures with weak uncertainty avoidance are contemplative, less aggressive, unemotional, accepting of personal risk, and relatively tolerant.

All four of these cultural dimensions relate to ethics in the sense that they may influence the individual’s perception of ethical situations, norms for behavior, and ethical judgments, among other factors. The implication is that as societies differ with regards to these cultural dimensions so will the various components of their ethical decision-making differ. The specific manner in which these cultural dimensions may influence ethical decision-making is discussed later, however.

A Framework for Marketing Ethics Decision-Making

In the field of moral philosophy, ethical theories have generally been classified into two major types, deontological and teleological (e.g., Beauchamp and Bowie 1979; Murphy and Laczniak 1981). The major difference between these two theories is that, whereas deontological theories focus on the specific actions or behaviors of an individual, teleological theories focus on the consequences of those actions or behaviors (Hunt and Vitell 1986). In other words, deontological theories are concerned with the inherent righteousness of a behavior or action, whereas teleological theories are concerned with the amount of good or bad embodied in the consequences of the behavior or action.

In their general theory of marketing ethics, Hunt and Vitell proposed that “cultural norms affect perceived ethical situations, perceived alternatives, perceived consequences, deontological norms, probabilities of consequences, desirability of consequences, and importance of stakeholders” (1986, p. 10). However, they did not specify how cultural norms affect ethical decision-making. The revised Hunt-Vitell (1992) general theory of ethics does not specify how cultural norms influence ethical decision-making either. Nor have empirical tests of the theory examined the influence of cultural norms on ethical decision-making (e.g., Vitell and Hunt 1990; Mayo and Marks 1990; Singhapakdi and Vitell 1990, 1991).

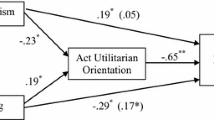

The primary task of this paper is the conceptualization of the impact of culture on the deontological and teleological evaluation of business practitioners. For example, with respect to one’s deontological evaluation, how important are factors such as organizational norms, industry norms, professional norms and personal experiences? Likewise, with respect to one’s teleological evaluation, how important are the various stakeholder groups such as the individual, his/her family, the organization, or other social units to which the individual is a member? Several propositions are formulated by applying Hofstede’s cultural typology to the proposals of the revised general theory of marketing ethics (Hunt and Vitell 1986, 1992). While Hunt and Vitell are specifically concerned with marketing ethics, their model is easily generalized to apply to all business situations. Figure 6.1 depicts their revised theory of ethics.

Propositions

Individualism/Collectivism Dimension

Based on Hofstede’s conceptualization of the individualism/collectivism construct, it is suggested that business practitioners from countries that are low on individualism would tend to be more susceptible to group and intraorganizational influence than their counterparts from countries that are high on this construct. Since individuals in these “collectivism” societies cannot easily distance themselves from the various groups to which they belong (including industry, professional and business groups) they will most likely be influenced by the norms of these groups. According to Hofstede, these groups protect the interests of their members, but in turn expect permanent loyalty (i.e., adherence to group norms). However, persons from more “individualist” societies, who are more concerned with their own self-interest, will tend to be influenced less by group norms.

According to Hofstede’s examination of various cultures and regions, Japan is characterized as low on individualism and high on collectivism, whereas the United States is high on individualism and low on collectivism. In support of this characterization of the United States, Robin and Reidenbach (1987) noted that the myriad of codes of ethics developed by organizations in the United States do not seem to have an effect on behavior. Additionally, Chonko and Hunt (1985) reported that codes of ethics are often developed and then put away; they are often not even introduced into the corporate culture. Consequently, their mere existence, without enforcement, is insufficient to affect ethical behavior. Based on the above rationale, and supporting empirical results, the following propositions were developed:

-

Proposition 1: Business practitioners in countries that are high on individualism (i.e., the U.S. or Canada) will be less likely to take into consideration informal professional, industry and organizational norms when forming their own deontological norms than business practitioners in countries that are high on collectivism (i.e., Japan).

-

Proposition 2: Business practitioners in countries that are high on individualism (i.e., the U.S. or Canada) will be less likely to take into consideration formal professional, industry and organizational codes of ethics when forming their own deontological norms than business practitioners in countries that are high on collectivism (i.e., Japan).

In a study conducted in the U.S. by Hegarty and Sims (1979), the personal desire for wealth was found to be positively related to unethical behavior. However, organizational profit goals, by themselves, did not have any significant influence on ethical behavior. Thus, U.S. marketers, appear more willing to behave unethically for personal gain than for corporate gain. On the other hand, in his work with respect to corporate culture, Ouchi (1981) noted that the typical Japanese organizational structure (the type Z organization) elicits significant organizational commitment from employees. Based on this and the preceeding arguments, the following propositions were formulated:

-

Proposition 3: Business practitioners in countries that are high on individualism (i.e., the U.S. or Canada) will be likely to consider themselves as a more important stakeholder1 than owners/stockholders and other employees.

-

Proposition 4: Business practitioners in countries that are high on collectivism (i.e., Japan) will be likely to consider the owners/stockholders and other employees as more important stakeholders than themselves.

Power Distance Dimension

This dimension suggests that business practitioners in countries with a large power distance are more likely to accept the inequality in power and authority that exists in most organizations, and, thus, they are more likely to accord individuals in prominent positions undue reverence compared to business practitioners in countries with a small power distance. The concept of power distance has been incorporated in studies of business ethics in different forms. Ferrell et al. (1983) used differential association theory to describe ethical/unethical behavior. This theory assumes that behavior is learned through the process of interacting with persons who are a part of intimate personal groups (Sutherland and Cressey 1970) such as one’s peers rather than one’s superiors. While this would be true in any society, it would be most likely in one with a small power distance where less reverence is given to the opinions of one’s superiors.

Ferrell and Gresham (1985) used both differential association theory as well as role-set theory to describe similar behavior patterns. A role-set refers to the relationship which focal persons have by virtue of their status in an organization. It is defined as the mixture of characteristics of significant others who form the role set, and may include their position and authority within the organization, as well as their perceived beliefs and behaviors (Ferrell and Gresham 1985).

These studies of the impact of differential association and the role-set constructs on behavior have reported that differential associations with peers (that is, the referent others closest to the focal person) were the strongest predictor of ethical/unethical behavior (Zey-Ferrell et al. 1979; Zey-Ferrell and Ferrell 1982). These findings can be interpreted to mean that, in countries such as the United States or Canada with a small or medium power distance, individuals look more to both their peers and informal norms than to their superiors and formal norms, for guidance on appropriate behavior. This does not mean that superiors do not influence ethical behavior; instead it simply means that in countries with a small distance their influence may be lessened.

However, in countries with a large power distance, superiors are expected to act autocratically without consulting subordinates. This would tend to indicate that a greater importance is given to both the cues of superiors and more formal norms in countries with a large power distance. Thus, the following propositions are presented:

-

Proposition 5: Business practitioners in countries with a small power distance (i.e., the U.S. or Canada) are more likely than business practitioners in countries with a large power distance (i.e., France) to take their ethical cues from fellow employees.

-

Proposition 6: Business practitioners in countries with a large power distance (i.e., France) are more likely than business practitioners in countries with a small power distance (i.e., the U.S. or Canada) to take their ethical cues from superiors.

-

Proposition 7: Business practitioners in countries with a small power distance (i.e., the U.S. or Canada) are likely to consider informal professional, industry and organizational norms as more important than formal codes of ethics when forming their own deontological norms.

-

Proposition 8: Business practitioners in countries with a large power distance (i.e., France) are likely to consider formal professional, industry and organizational codes of ethics as more important than informal norms when forming their own deontological norms.

Uncertainty Avoidance Dimension

Based on Hofstede’s conceptualization of this dimension, it is suggested that business practitioners from societies that are strong on uncertainty avoidance are more likely to be intolerant of any deviations from group/organizational norms than their counterparts from countries that have weak uncertainty avoidance. As an example, the United States and Canada are characterized by Hofstede as having weak uncertainty avoidance, whereas Japan is characterized as strong on this dimension. This characterization suggests that business practitioners in Japan are more likely to be intolerant of any deviations from group/organizational norms than their North American counterparts. Since deviants are not expected to be tolerated, membership in most organizational groups in Japan is expected to be composed of mostly non-deviants in comparison to the United States or Canada.

This reasoning concurs with Ouchi’s (1981) theory regarding organizational cultures in Japanese and American firms. Ouchi states that type Z organizations (i.e., Japanese firms) have a high degree of consistency in their internal cultures. These firms involve intimate associations of people who are tied together through a variety of bonds. In contrast to a hierarchical organization (i.e., American firms) where there is a great deal of mistrust, the individual in the type Z organization naturally seeks to do that which is in the common good.

In a study of U.S. research firms, data subcontractors, and corporate research departments, Ferrell and Skinner (1988) reported that in the absence of formalized standards and codes of conduct, the acceptability of various activities and procedures (ethical or unethical) was ambiguous. Thus, business and marketing research practitioners in the U.S. may sometimes accept unethical behavior, especially where there is no formal standard or rule to guide that behavior. According to the theories of both Hofstede and Ouchi, this would be much less likely within a Japanese firm. Thus, the following propositions have been formulated:

-

Proposition 9: Business practitioners in countries that are high in uncertainty avoidance (i.e., Japan) will be more likely to consider formal professional, industry and organizational codes of ethics when forming their own deontological norms than business practitioners in countries that are low in uncertainty avoidance (i.e., the U.S. or Canada).

-

Proposition 10: Business practitioners in countries that are high in uncertainty avoidance (i.e., Japan) will be less likely to perceive ethical problems2 than business practitioners in countries that are low in uncertainty avoidance (i.e., the U.S. or Canada).

Related to the concept of uncertainty avoidance is the belief that one can predict the actions of members of a social unit, such as a family or social group, of which one is a member. Societies that are strong in uncertainty avoidance and, therefore, intolerant of deviants, can be expected to have a high degree of accuracy in predicting the actions of individuals who share the membership of any social unit. Therefore, it is expected that for individuals to continue to be members of a social group, the consequences of their actions must be perceived by the membership to be desirable to the majority of the group members. For example, it is not uncommon for a Japanese CEO to relinquish his position if he perceives that his actions have had undesirable consequences for the firm. However, in the United States, this is seldom the case. Irrespective of the consequences of their actions for the firm, the typical U.S. CEO is likely to resign only when compelled to do so. Thus, we have developed the following propositions:

-

Proposition 11: Business practitioners in countries with high uncertainty avoidance (i.e., Japan) will be more likely to perceive the negative consequences of their “questionable” actions than business practitioners in countries with low uncertainty avoidance (i.e., the U.S. or Canada).

-

Proposition 12: Business practitioners in countries with high uncertainty avoidance (i.e., Japan) will be likely to consider the owners/stockholders and other employees as more important stakeholders than themselves.

-

Proposition 13: Business practitioners in countries with low uncertainty avoidance (i.e., the U.S. or Canada) will be likely to consider themselves as more important stakeholders than the owners/stockholders and other employees.

Masculinity/Femininity Dimension

The masculinity/femininity dimension suggests that there are some cultural environments that are more conducive to unethical conduct than others. Societies that are characterized as masculine encourage individuals, especially males, to be ambitious, competitive and to strive for material success. These factors may contribute significantly to one’s engagement in unethical behavior.

Sweden, for example, is classified by Hofstede as a feminine culture, whereas the United States and Japan are classified as masculine cultures. This characterization implies that, compared to the United States and Japan, Sweden defines more overlapping social roles for both men and women, and neither gender needs to be overly ambitious or competitive. In fact, some practices, such as high pressure selling, that are seen as just good business in a “masculine” culture may be considered as unethical by many in a more “feminine” culture. Thus, decision-makers in some cultures (i.e., masculine) may not even perceive certain ethical problems because they are not defined by their culture as involving ethics. Given this characterization, the following propositions were formulated relative to the masculinity/femininity dimension:

-

Proposition 14: Business practitioners (both males and females) in countries high in “masculinity” (i.e., the U.S. or Japan) will be less likely to perceive ethical problems than business practitioners (both males and females) in countries characterized as high in “femininity” (i.e., Sweden).

-

Proposition 15: Business practitioners (both males and females) in countries high in “masculinity” (i.e., the U.S. or Japan) will be less likely to be influenced by professional, industry and organizational codes of ethics than business practitioners (both males and females) in countries characterized as high in “femininity” (i.e., Sweden).

Testing the Propositions

One of our objectives in developing this synthesis of business ethics and culture was to derive testable propositions. However, before these propositions can be tested, they must first be transformed into research hypotheses by adding specificity to them and by developing a taxonomy of moderator variables involving the other factors than can affect ethical decision-making in the workplace such as the industry environment, the organizational environment, the professional environment and personal characteristics.

Because of the nature of the propositions, the authors believe that survey procedures would be more appropriate than experimentation for testing them. Surveys used in empirical studies involving marketing ethics (e.g., Reidenbach et al. 1991; Mayo and Marks 1990; Singhapakdi and Vitell 1991) have been shown to be an efficient and practical method of examining various propositions. Irrespective of the survey instrument used, it is hoped that appropriate measures will be taken in translating the instrument into foreign languages, while at the same time retaining the original meanings of the items in the instruments (Dant and Barnes 1989).

Ideally, business practitioners from several countries would need to be included in any study so that the individual effects of the four different dimensions could be accurately measured. While we understand the difficulty in doing this, and the fact that several studies may actually be needed, we, nevertheless, consider it to be a worthwhile research endeavor.

Conclusions

Most studies on ethical issues in business, while focusing on moral philosophies, merely provide descriptive statistics about ethical beliefs and significant covariations of selected variables. In the context of theory building, there are a number of models that have been offered; however, few empirical tests of these models have been attempted and none have adequately examined the cultural dimension.

The objective of this paper has been to integrate the conceptual propositions of theory in business ethics with a typology of cultural dimensions. However, while the cultural dimensions were developed after extensive research involving several different countries and cultures, only parts, of the selected models of business ethics have been tested and supported.

While recognizing that there are many factors (e.g., cultural environment, industry environment, organizational environment, personal characteristics and professional environment) that can influence ethical decision-making, since the primary objective of this paper was to show how the different cultural dimensions impact on the ethical decision-making process across different societies, the propositions offered concern only the influence of culture. The propositions derived are sufficiently explicit so as to be used to generate empirically testable research hypotheses, and we offer them for that purpose.

These propositions, if tested, could help individual firms that are operating in multinational markets to identify some of the inherent differences in the behavior of their employees across different cultures. It might also help in identifying those management actions that will most likely result in “ethical” behavior on the part of employees, management actions that may differ from culture to culture. For example, management may wish to emphasize formal codes of ethics in some countries and more informal ones in other countries.

Notes

-

1.

A specific individual or group of individuals perceived by the decision-maker to be affected by his/her decisions.

-

2.

A problem or dilemma, facing the decision-maker, that is perceived by the decision-maker as involving an ethical issue.

References

Bartels, R. 1967. A model for ethics in marketing. Journal of Marketing 31: 20–26.

Beauchamp, T.L., and N.E. Bowie. 1979. Ethical theory and business. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Chonko, L.B., and S.D. Hunt. 1985. Ethics and marketing management: An empirical examination. Journal of Business Research 13: 339–359.

Dant, R., and J.H. Barnes. 1989. Methodological concerns in cross-cultural research: Implications for economic development. In Marketing and development: Toward broader dimensions, research in marketing supplement, vol. 4, ed. E. Kumcu and A.F. Firat, 149–171. Greenwich: JAI Press.

Ferrell, O.C., and L.G. Gresham. 1985. A contingency framework for understanding ethical decision making in marketing. Journal of Marketing 49: 87–96.

Ferrell, O.C., and S.J. Skinner. 1988. Ethical behavior and bureaucratic structure in marketing research organizations. Journal of Marketing Research 25: 103–109.

Ferrell, O.C., M. Zey-Ferrell, and D. Krugman. 1983. A comparison of predictors of ethical and unethical behavior among corporate and agency advertising managers. Journal of Macromarketing 3: 19–27.

Hegarty, W.H., and H.P. Sims. 1979. Organizational philosophy, policies, and objectives related to unethical decision behavior: An laboratory experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology 64(3): 331–338.

Hofstede, G. 1979. Value systems in forty countries: Interpretation, validation, and consequences for theory. In Cross-cultural contributions to psychology, ed. L.H. Eckensberger, W.J. Lonner, and Y.H. Poortinga, 398–407. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Hofstede, G. 1980. Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Hofstede, G. 1983. Dimensions of national culture in fifty countries and three regions. In Expiscations in cross-cultural psychology, ed. J.B. Deregowski, S. Dziurawiec, and R.C. Annios, 335–355. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Hofstede, G. 1984. The cultural relativity of the quality of life concept. Academy of Management Review 9(3): 389–398.

Hunt, S.D., and S. Vitell. 1986. A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing 8: 5–16.

Hunt, S.D., and S. Vitell. 1992. The general theory of marketing ethics: A retrospective and revision. In Ethics in marketing, ed. J. Quelch and C. Smith. Chicago: Richard D. Irwin.

Mayo, M.A., and L.J. Marks. 1990. An expirical investigation of a general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 18(2): 163–171.

Murphy, P., and G.R. Laczniak. 1981. Marketing ethics: A review with implications for managers, educators and researchers, Review of Marketing, 251–266.

Ouchi, W.G. 1981. Theory Z. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Reidenbach, R.E., D.P. Robin, and L. Dawson. 1991. An application and extension of a multidimensional ethics scale to selected marketing practices and marketing groups. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 19(2): 83–92.

Robin, D.P., and R.E. Reidenbach. 1987. Social responsibility, ethics, and marketing strategy: Closing the gap between concept and application. Journal of Marketing 51: 44–58.

Singhapakdi, A., and S.J. Vitell. 1990. Marketing ethics: Factors influencing perceptions of ethical problems and alternatives. Journal of Macromarketing 10: 4–18.

Singhapakdi, A., and S.J. Vitell. 1991. Research note: Selected factors influencing marketers’ deontological norms. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 9(1): 37–42.

Sutherland, E., and D.R. Cressey. 1970. Principles of criminology, 8th ed. Chicago: Lippincott.

Vitell, S.J., and S.D. Hunt. 1990. The general theory of marketing ethics: A partial test of the model. Research in Marketing 10: 237–265.

Zey-Ferrell, M., and O.C. Ferrell. 1982. Role-set configuration and opportunity as predictors of unethical behavior in organizations. Human Relations 35(7): 587–604.

Zey-Ferrell, M., K.M. Weaver, and O.C. Ferrell. 1979. Predicting unethical behavior among marketing practitioners. Human Relations 32: 557–569.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Vitell, S.J., Nwachukwu, S.L., Barnes, J.H. (2013). The Effects of Culture on Ethical Decision-Making: An Application of Hofstede’s Typology. In: Michalos, A., Poff, D. (eds) Citation Classics from the Journal of Business Ethics. Advances in Business Ethics Research, vol 2. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4126-3_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4126-3_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-4125-6

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-4126-3

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)