Abstract

Although demand for evidence-based policies and programs to reduce population health inequities is intensifying, the influence of social epidemiology on public policy remains limited. In clinical and health services research domains, knowledge translation strategies have been developed to increase the impact of research evidence in policy making and practice. We review the applicability of these strategies for increasing the practical impact of social epidemiology research, drawing on the knowledge constitutive interests framework developed by Jürgen Habermas. We find that conventional knowledge translation characterizes policy change and the role of research in technical-instrumental terms that do not reflect the complex social, political and values-based dimensions of policy change and research use that come into play in relation to the reduction of health inequities. While conventional knowledge translation approaches may work in some cases, for social epidemiology to play a significant role in advancing social change, knowledge translation strategies that acknowledge and respond to the intersections of power, politics, values and science also need to be developed.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

The World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health (2008) called action on the determinants of health an “ethical imperative.” Social epidemiologists should have important roles to play in the Commission’s call to action. Social epidemiology has identified a number of important relationships between socioeconomic inequality and population health. Moreover, the measurement tools and conceptual constructs developed by social epidemiologists can be used to evaluate health outcomes associated with policy and program interventions both inside and outside of the health care system (Oakes and Kaufman 2006; Berkman and Kawachi 2000; Braveman 2006). This research evidence should be particularly valuable for guiding policy initiatives to reduce health inequities (Graham 2004). However, the influence of social epidemiology on current public policy making in North America remains relatively hard to see (Raphael 2003; Asthana and Halliday 2006). In this chapter we ask, why doesn’t health equity research in particular, and social epidemiology in general, have a bigger role to play in promoting social and political change? Simply put, in this chapter, we argue that the answer lies in the fact that the tools available, which we designate here as “conventional” knowledge translation, assume that research knowledge is to be used for solving problems; whereas, social epidemiology, at its core, often emphasizes deeper and quite distinct goals of explanation and, ultimately, social change.

There are many ways to explain the limited policy impact of social epidemiology, several of which are explored in other chapters in this book (see Chaps. 1, 3 and 15). Our approach is to look at the tools and techniques that are offered to health researchers in the rapidly expanding research utilization or, what is more frequently referred to as, knowledge translation (KT), literature. These tools are intended help make health research relevant and to move health research into practice and policy. In what follows we ask, first, “What were these tools designed to do?” and, second, “Are these tools suited to health equity research and the goals of social epidemiologists?”

This chapter proceeds as follows. First, we outline our assumptions about some of the defining characteristics of social epidemiology. These assumptions inform all of our observations that follow; therefore, we feel it is important to state them at the outset. Next, we briefly introduce conventional KT, as it has emerged and gained prominence in health research communities in Canada and elsewhere. With this foundation, we identify four core premises underpinning conventional KT and critically assess the relevance of these premises for social epidemiology and policy challenges related to health inequities. As an alternative, and drawing on the work of Jürgen Habermas, we suggest that conventional KT, which was designed to advance the practical impact of clinical and health services research, emphasizes an instrumental (problem-solving) role for research knowledge in society. In contrast, social epidemiology is characterized by hermeneutical (explanatory) and emancipatory (equity-seeking) goals (Habermas 1971). These are fundamentally different approaches to knowledge use, and, we will argue, they give rise to different approaches for bridging the gap between research and practice. Consequently, conventional KT tools and techniques will often be ill-suited and inadequate for advancing the impact of social determinants of health research. We conclude with an outline of an alternative KT framework that may be more appropriate for social epidemiology to increase its impact on social policy. Simply put, it encourages social epidemiologists to either align themselves more closely with the instrumental approach to KT in clinical and health services research and move from problem-focused to solution-focused research or move to a form of engaged scholarship. The latter involves researchers becoming more active and engaged as true public intellectuals or, more simply, by actively engage with the media, speaking out on issues that contribute to the health of marginalized populations and becoming active members of advocacy coalitions and other forms of collective action to reform health and social policy. This latter framework takes power, politics and values seriously in strategies to promote social change through research. In other words, social epidemiology is a heterogeneous enterprise and social epidemiologists need to find the KT approach that fits their needs.

2 Starting Assumptions About Social Epidemiology

Neither of us is a social epidemiologist, but our arguments in this chapter rest on some core assumptions that we have made about social epidemiology (particularly, health equity research) as a knowledge project. First, we understand social epidemiology as a project that explicitly investigates social, economic and political determinants of health, disease and wellbeing in populations (Krieger 2001). Second, most social epidemiology research is scrupulously positivist, aiming to produce falsifiable, empirical measures of these relationships. Third, we are assuming that researchers in social epidemiology and related disciplines face increasing pressure from research funding agencies and others to increase the practical impact of their scientific activity even if this practical orientation is in tension with the very nature of the discipline.

Thus, we are also assuming that, unlike almost all other health science disciplines, social epidemiology has, implicitly if not explicitly, a strong normative dimension, one that emphasizes social critique. Social epidemiology illuminates harmful effects of social conditions on health so that (eventually) the relevant social conditions can be targeted and modified and so that population health can be improved (Berkman and Kawachi 2000; Wilkinson and Pickett 2009; Chernomas and Hudson 2009). Finally, precisely because social epidemiology has the potential to inform radical change, we assume that social epidemiologists are genuinely interested in contributing to practical population health improvement but that they may also feel constrained by what they, and others, see as their roles as scientists.

3 Making Research Relevant: A Cursory Look at the Emergence of Knowledge Translation in the Health Sciences

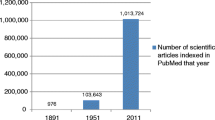

The last two decades have been marked by the demand for research, in fields as varied as international development, energy and environmental science and even the social sciences and humanities, to demonstrate practical value and return on investment (Murphy and Topple 2003; Buxton et al. 2004). Perhaps nowhere has this demand been expressed as urgently as it has been in relation to health services and health research. Concern for health research to show practical impact is due, in part, to unprecedented cost pressures from health care experienced in most Western countries over this period and a universal need for strategies to contain expenses while also making people healthier (Limoges et al. 1994).

While the role of research in practice and policy making has received longstanding attention in some scholarly disciplines (e.g., science and technology studies, sociology and political science) (Bernal 1939; Merton 1973; Rose and Rose 1970), research utilization is a relatively new focus of attention in the health sciences. Since the late 1990s, Canadians – who pioneered the evidence-based medicine movement (Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group 1992; Sackett et al. 2000) and who have also been leaders in advancing the argument for health research utilization (Lemieux-Charles and Champagne 2004) – have bundled these ideas under the concept of knowledge translation or KT (Straus et al. 2009a, b). Canada’s premier federal health research funding agency, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), has adopted KT as a core mandate and defines it as “the exchange, synthesis and ethically-sound application of knowledge – within a complex system of interactions among researchers and users – to accelerate the capture of the benefits of research for Canadians through improved health, more effective services and products, and a strengthened health care system” (Tibelius and Stirling 2007). Other allied terms used to describe this concept may be more familiar to some readers, such as knowledge transfer, knowledge mobilization, linkage and exchange, research transfer, implementation and dissemination or research uptake. Implementation science is a newer term, describing evaluative research to assess the effectiveness of KT strategies (BiomedCentral 2010). Because KT is an expression that is widely gaining ground in other countries (Pablos-Mendez and Shademani 2006), and other disciplinary domains (Carden 2009), it is the term that we will use throughout this chapter.

KT frameworks for health are premised on perceived structural and/or cultural gaps between the individuals and organizations responsible for health care delivery and those responsible for conducting research. However, KT assumes that scientific publication in peer-reviewed journals is too passive a dissemination practice for there to be a real impact of research on policy, programs and practice.

As outlined in Table 13.1, knowledge translation is different from traditional scientific dissemination in at least three important aspects: (1) the intended audience for research extends far beyond academe to include practitioners and decision makers; (2) the goal is not only to inform but to have an effect on decisions and problems; and (3) the method of knowledge sharing involves active outreach on the part of the research community (Graham and Tetroe 2007).

Explicit and implicit assumptions about the nature of the research/decision-making divide and the proper role of scientific knowledge in policy development have given rise to different recommendations for KT activities; however, all approaches tend toward agreement that “tailor and target” approaches are the best strategies for enhancing the practical influence of research evidence. From these directives we can derive a set of boilerplate KT principles to guide health researchers:

-

Understand the decision maker’s problem from the decision maker’s point of view;

-

Interact closely with that decision-making individual or organization to ensure the research project explores aspects of the problem and potential solutions that matter to the decision maker; and

-

Explain the research results to the decision maker in terms that are meaningful and actionable and that help the decision maker to solve the problem.

The question then becomes whether and to what extent these core KT principles are an effective guide for social epidemiology. In our view the answer is often “no” because of tensions (if not a fundamental disconnect) between some of the core assumptions that underlie conventional approaches to KT and at least parts of the project that is social epidemiology.

4 The Tension Between Conventional KT and Social Epidemiology

In our view, conventional KT may not be particularly useful for increasing the impact of social epidemiology on policy, program and practice choices. We want to show how conventional KT is not always relevant or effective for social epidemiology for three reasons: first, because KT understands in terms of problems, not processes; second, because KT targets individual rather than collective action; third, because it assumes shared, rather than contested definitions of policy problems; and fourth and finally, because conventional KT leaves little room for advocacy.

4.1 KT Understands Policy Change in Terms of Problems, Not Processes

First, as KT moves from clinical settings to the policy process, it retains a framework that emphasizes problem-solving, characterized in terms of discrete decision events that are closely linked to, if not elided with, implementation of evidence-based solutions. For example, in clinical settings the theory is that effective KT will make it more likely that clinicians will follow clinical practice guidelines. As a result, one of the metrics for evaluating conventional KT more generally is whether or not problems get solved and decisions are made to bring relevant rules and procedures into line with the best available evidence. While the impact of conventional KT on clinical decision making has been mixed, the complex implications for policy and program change that may be generated through social epidemiology defy the reduction of evidence to decision support and the reduction of policy making to problem solving.

For a government to respond to the implications, for example, of a report on correlations between housing affordability and health status in a given jurisdiction (Dunn 2002), it would likely require negotiation and coordination across multiple departments, agencies and levels of government and would operate over a number of years (Leone and Carroll 2010). A problem-solving/solution-implementation model, based on clinical decision making for an individual patient is an obviously inadequate analogy for such wide-sweeping, systems-level policy change (Howlett et al. 2009).

A variety of conceptual frameworks are available from policy studies that can generate more nuanced accounts of policy change related to social determinants of health compared to models based on evidence-based medicine. We have shown elsewhere that the developmental stages framework of policy making can be a particularly useful heuristic model for advancing KT (Fafard 2008). The framework emphasizes that policy making involves much more than simple decision making. First, an issue or problem has to become part of the government’s agenda. Second, the range of possible responses to the policy challenge, including doing nothing, have to be evaluated against a diverse range of criteria, of which scientific evidence is but one such criterion. Third, a decision gets made for almost any complex policy problem, and deciding what to do usually involves a series of decisions by a diverse set of actors over a period of time. Once a decision has been made the preferred course of action is implemented where the substantive content of the decision sometimes gets modified. Finally, in a well-performing policy-making system, policy decisions are routinely evaluated and, as appropriate, changes made (Deleon 1999). Although it is by no means the dominant model of policy making in contemporary policy studies, the stages model does underline the reality that there are multiple points in the policy process when research evidence may be influential, and it helps explain that different barriers to research use may be relevant at different stages (Burton 2006).

Especially important for health equity research, the stages model flags agenda setting as the critical first step in policy development. Before research evidence can ever influence a government to solve a problem, there is the prior step of deciding that the problem exists, that it matters and that it can be addressed. Faced with literally thousands of issues that it could focus on, a government selects a platform, or portfolio of target issues, which it believes it has the power, resources and political support to change (Kingdon 2003). Of course, research evidence is but one determinant of the agenda of a government. The ideational and ideological preferences of the governing party, the personal preferences and concerns of individual ministers and public opinion all play a role. However, research can be, and often is, an important influence on the government’s agenda. Evidence from social epidemiology could play particularly important roles in the agenda-setting stage of policy change, for example, by presenting normative and empirical arguments as to why, from a population health perspective, it is important to invest in early childhood development, traffic ordinances or community empowerment initiatives. Moreover, the impact of research, including social epidemiologic research on the agenda of a government, is by no means automatic. Here, notwithstanding its limitations, the conventional KT literature does point to potentially useful processes and practices (e.g., plain language summaries, knowledge brokering, etc.). But agenda setting is rarely accounted for in the metrics of conventional KT, which emphasize problem solving and implementation of policy solutions.

4.2 Conventional KT Is Concerned with Individual, Not Collective, Action

KT emphasizes the need to identify the key decision maker (or decision-making organization) involved in the policy or practice issue that is being researched and to narrowly tailor the research question and the research findings to address the concerns of, and actions available to, this decision maker. In conventional KT it is routinely asserted that evidence that is not tailored for a target audience is less likely to be reviewed or adopted into use (Graham and Tetroe 2007). Another commonplace assertion is that “linkage and exchange” activities to engage the decision maker directly in the research process will produce research evidence that is more relevant and more likely to be applied in practice. Yet these narrow “target and tailor” approaches emphasize action within rather than across jurisdictional boundaries, and they are aimed to trigger an individual response rather than collective action.

Leaving aside the question of whether focusing on a single target audience is a good way to bring about clinical or health system change, it is surely an unpromising approach when it comes to the social determinants of health. Which sector, for example, would be the ideal participant and target audience for research related to mental health among homeless populations? Should researchers foster linkages with representatives in the housing, income assistance and social welfare or health care sectors? In some instances, the relevant government audience for social epidemiology may not exist at all, for example, when researchers look at macro-level issues beyond the reach of the current government (e.g., correlations between infant mortality and types of political regimes) (Coburn 2000). However, results of this type of social epidemiologic research may be of interest to the media and to civil society groups that are influential in the policy-making process, although they are not “decision makers” per se.

As these examples suggest, target audiences for social epidemiology research are likely to comprise a wide range of stakeholders working within, across, beyond and sometimes against governments. Effective response to social determinants of health research will almost always require collective action, negotiation and coordination that move us quickly into the realm of politics. Yet conventional KT, which encourages researchers to narrowly target research findings to guide individual decisions, has relatively little to say about collective action or the political dimensions of decision making. Consequently, it offers limited guidance to social epidemiologists who aim to make their research useful to the diversity of actors with a stake in the social determinants of health.

4.3 Conventional KT Assumes Shared, Not Contested, Definitions of Problems

Central to the conventional KT literature is the tacit assumption that researchers and policy stakeholders will agree on the meaning of a common policy problem; that is, they accept the same framing of the problem (Dorfman et al. 2005). This discursive agreement is required to generate evidence-based recommendations that are salient to, and executable within, a decision maker’s range of action and priorities. A further step is to include government and health system officials directly in the research process either by means of the aforementioned linkage and exchange or what some have called integrated KT (Gagnon 2011).

When an issue is generally uncontroversial (or it is relatively technical in nature), researchers, policy makers and the wider communities that are affected may share a common definition of the problem. This situation is often the case for some (but certainly not all) clinical or health services issues. However, many social determinants of health problems and most health equity issues are decidedly not uncontroversial because they concern unequal distribution of resources across population groups. These kinds of distributive justice problems are complex and informed by social values. They cannot be addressed through technical or administrative changes alone (Daniels 2008). In these cases, researchers and the array of different decision makers and community representatives with a stake in this issue may have widely divergent interpretations of both the problem and the salient solutions. Contested definitions of social determinants of health issues are particularly vivid when the policy issues are related to stigmatized or illegal health behaviours (e.g., substance use) or marginalized populations (e.g., sex trade workers) (Benoit et al. 2003). For example, there is a multitude of competing ways of framing illicit substance use, including addiction and pathology, criminality, mental illness and self-medication, cultural deprivation, et cetera. These different meaning frames will lead participants to different accounts of what matters in relation to substance use, what needs to be done and who is responsible for doing it.

Importantly, these diverse discourses are not equally authoritative or persuasive. Rather, the authority to name or frame a problem and make it stick is a marker of power, and the struggle to challenge, refute and redefine meaning frames through discourse is the stuff of politics (Bevir and Rhodes 2006). In other disciplines, including sociology, communications and critical public health, researchers have used discourse analysis methods to shed light on the ways that policy debates and struggles for social change often coalesce around the authority to name and assign meaning to social phenomena. A discourse analysis approach may be particularly useful for social epidemiologists to draw upon, because it helps to explain tensions that that may arise frequently in relation to contentious health equity research and KT (Bacchi 2008; Murphy and van der Meulen 2008). Here, the goal of close collaboration between researchers and decision makers is a challenging proposition to say the least.

Indeed, important goals of health equity research may be to resist how powerful constituencies define issues affecting marginalized populations and to encourage stakeholders to understand problems in a new light. For example, social epidemiologists have contributed to a partial shift in the approach to homelessness in Canada by providing evidence that homelessness is a critical health care problem in addition to being a social assistance issue (Frankish et al. 2005). Weiss (1979) calls this kind of influence the “enlightenment” model of research use. However, conventional KT provides minimal guidance about how to advance controversial research evidence among decision makers, and, in the same way that it is unconcerned with agenda setting (see above), KT also accords relatively little value to research effects that are reflected in changed attitudes rather than changed actions.

There is ample research that demonstrates how knowledge (including research-based knowledge) can be used to produce, concentrate and exercise discursive power in ways that privilege some definitions of health and social problems and marginalize others. To take but one example, some research on autism emphasizes intensive behavioural interventions to “treat” autistic individuals. Other research focuses on trying to better understand what explains the increased incidence of autism including what some believe to be the cause of autism (e.g., environmental factors and the falsely attributed measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine). Still other research, often encouraged by autistic adults, sees autism as a form of neurological diversity that, rather than being cured or treated, should be recognized as a legitimate identity. Each of these research endeavours generates knowledge that leads to quite different definitions of the “problem” of autism and what might be the most appropriate “solutions” (Orsini and Smith 2010). Yet the conventional health KT framework tends to assume a naturalistic and uncontested approach to defining policy issues and research questions.

4.4 Conventional KT Leaves Little Room for Advocacy

Conventional KT often assumes a strict division between “research” (i.e., the creation of knowledge) and “advocacy” (i.e., making the public case for a preferred policy decision). Researchers including social epidemiologists are expected, of course, to do research, but the conventional model of KT leaves little or no room for subsequent public advocacy. This division partly results from the fact that, in conventional KT, when the value commitments in the research are aligned with those of the decision maker, we call it knowledge translation; when they do not so align, we call it advocacy.

In fact, social and policy change is often the result of disagreement and contestation, if not outright conflict, and public advocacy is sometimes required. Policy choices often involve normative disagreements that are resolved, not by more research, but by public discussion and debate where more or less acceptable compromises are arrived at. Even in those cases where there is little disagreement on the basic epidemiologic research, say for example on the correlation between health status and inequality, there remains considerable room for debate and discussion on what the causal linkage is and, even when this is established, what the optimal policy response might be.

Some social epidemiologists accept, and may even encourage, some or all of the assumptions of conventional KT even when their research has significant policy implications. They are comfortable in the role of researcher separate and apart from the policy discussion. Their preference to not engage in policy advocacy is simply a reflection of the fact that they feel they have neither the training nor the necessary expertise that would allow them to move from research to policy and much less to advocacy.

However, many other social epidemiologists are unwilling to limit their role to that of just research. They are part of the longstanding public health tradition of advocating for social, political and economic change. While on occasion, collaborative work with decision makers may be appropriate and effective, they believe that very often advocacy and public debate are required, particularly when research threatens to disrupt the status quo. Thus, some researchers feel an obligation to speak for (or at least with) constituencies affected by health problems that may not have the social capital to champion research findings to influence programs and policy themselves. Indeed, for many, one of the reasons for doing social epidemiologic research in the first place is to foster meaningful change and concerted action on the social causes of health inequality.

Moreover, these are rarely, if ever, solo activities. Policy discussion and debate involves groups of people with differing perspectives on the topical issues of the day who sometimes align themselves to make the case for policy change. Thus, social and political change means becoming part of a more or less organized group or, what political scientists have called, an “advocacy coalition” (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1999). Why should a social epidemiologist join an advocacy coalition? Simply put, advocacy coalitions are a logical response to the nature of policy and program change. Given the sheer complexity of most policy problems (e.g., how to reduce overcrowding in inner city housing) and similarly the complexity of the appropriate response from governments (e.g., social housing, rent controls, increased minimum wage, etc.), not to mention the complexity of government decision making (e.g., how to work with a city council committed to low taxes in order to expand the stock of social housing), advocacy coalitions bring together a range of expertise on how best to define the problem, how to design effective and feasible policy and program responses and, of course, how to most effectively pressure governments to make policy changes.

For some, the goal is not to influence the decision of the government of the day but rather to fundamentally challenge the status quo. This takes us beyond the confines of KT and requires a different way of thinking about the role of knowledge, power and social change that we now wish to sketch, if only briefly.

5 KT and Knowledge Constitutive Interests

All told, these examples point to quite a bad fit between the context of research application presupposed in conventional KT frameworks and the actual conditions of health equity policy making that many social epidemiologists will encounter. As a result, many techniques recommended in the KT literature will be difficult for social epidemiologists to execute, and these techniques may be suboptimal or even inappropriate interventions to help increase the practical value and impact of social epidemiology evidence. If it has not already, this impediment threatens to become a serious problem for the discipline, considering not only the urgent need for informed practical action to reduce health inequities but also the increasing likelihood that research funding will be tied to evidence of research impact. Therefore, explaining and resolving social epidemiology’s KT obstacles are important.

In the short space remaining in this chapter, we sketch our approach to these challenges. Central to our argument here is the work of Jürgen Habermas (1971), a sociologist of knowledge and political philosopher whose analyses of modernization, communicative rationality and democratization are directly relevant for understanding the discourse on KT. His early research included the elaboration of a conceptual framework for understanding three distinct purposes for (or interests in) using knowledge in society. The theory of knowledge constitutive interests helps to explain the “bad fit” we find between KT and social epidemiology, and it suggests directions for increasing social epidemiology’s chances of having an effect.

Under the knowledge constitutive interests framework, knowledge may be used for instrumental purposes (i.e., controlling conditions in the natural world and technical problem solving); hermeneutical purposes (i.e., facilitating communication and understanding of the social world); and emancipatory purposes (i.e., overcoming domination and rationality). An instrumental interest in knowledge is rooted in the deep-seated desire we have to predict and control natural phenomena. Positivism sees knowledge in these terms; hence, much of what we consider scientific research produces what Habermas would call instrumental knowledge. However, he argues that there is a second, equally deep-seated hermeneutical interest in explaining social relationships and improving our capacity for intersubjective understanding. Habermas classifies many of the social sciences and humanities disciplines as belonging to this domain. Finally, there is the emancipatory interest to challenge oppression. Here, we use knowledge to guide critical self-reflection and critical analysis of institutional forces and relationships that limit our options and our capacity for rational action.

Habermas’ framework sheds some light on the problems that conventional KT poses for social epidemiology. First, as we have noted, KT was developed to increase the use of research evidence in solving advanced technical problems, particularly in clinical medicine. Despite limited evidence of the comparative effectiveness of different KT strategies in clinical and health care services, systematic reviews of evidence have been used to develop guidelines for treatment of coronary heart disease (Helfand et al. 2009; Mosca et al. 2004); the integrated knowledge-action cycle has supported nurses’ implementation of best practices in wound care (Graham et al. 2007); and linkage and exchange approaches have been associated with increased use of clinical evidence in large health care provider organizations (Lomas 2003). In these and countless other cases, conventional KT strategies have been aimed to support decision makers in addressing biomedical outcomes through technical interventions.

In terms of the knowledge constitutive interests framework, these KT approaches should be understood as supporting instrumental objectives. They were not aimed to advance use of knowledge for hermeneutical (i.e., improving understanding of social relationships) or emancipatory (i.e., advancing rationality and social justice) objectives. That is to say, these KT approaches were not designed to support the practical impact of social epidemiology. Regardless of its positivist methodological principles, social epidemiology is, at least in our reading of it, fundamentally a hermeneutical knowledge project aimed to explain social relationships that affect health. In light of its focus on unequal social relations and health, it also has a strong orientation toward social critique and emancipatory interests. The overwhelming evidence furnished by social epidemiology of the “social gradient in health” is knowledge that explains and provides rational-normative grounds for critiquing the fact that population health differences are unnatural, complex problems that inequitably limit life chances for some groups. Problems such as these are problems shaped by politics, power and values, and they cannot be resolved through instrumental-technical means alone.

6 Taking Politics, Power and Values Seriously in KT

How can social epidemiology respond to these epistemological contradictions with conventional KT and contribute more effectively to equity in social and health policies? We see two potential approaches, both of which are being pursued by social epidemiologists with whom we collaborate around KT approaches, including many of the authors represented in this book. The first involves asking different research questions; the second involves adopting different roles for researchers as actors in policy and social change. Regardless of which path social epidemiologists follow, important revisions to the conventional framework for KT will be required.

On the one hand, researchers can reorient their inquiry and KT projects toward more strategic, technical problem-solving initiatives in order to better support government or service provider stakeholders. Here, social epidemiology aligns more closely with the instrumental approach to KT in clinical and health services research. This might mean, for example, initiating fewer studies to assess correlations between social disparities and health and undertaking more studies to evaluate the relative effectiveness of this or that programmatic intervention under prevailing socioeconomic conditions. A focus on interventions is more likely to have an effect on policy and program choices if only because of the clear link between cause and effect; whereas, studies that emphasize correlations often do not specify the causal pathway in sufficient detail (if at all) to provide guidance for policy and program change. This approach has recently been described as addressing social versus societal determinants of health (Krieger et al. 2010). It is explored in some detail in other chapters (see Chaps. 1 and 12) in terms of a shift in social epidemiology from problem-focused to solution-focused research.

The other option is to look for alternative KT practices and markers of KT success that may be more consonant with the hermeneutical and emancipatory presuppositions of critical social epidemiology. For example, researchers may seek out more active and engaged roles as public intellectuals by participating in public and social media, speaking out on issues of major importance for the health of marginalized populations and also contributing purposively in advocacy coalitions and other forms of collective action to reform health and social policy. While there are no guarantees that social epidemiologic research will have a greater impact on policy and program choices when researchers take on these roles, this approach does reflect the realities of policy making in a democracy where scientific evidence, however compelling, is rarely the sole impetus for policy change.

Of course, these are roles that some social epidemiologists have traditionally been reluctant to pursue because, as we suggested earlier, they are concerned to protect the privileged status of the research that comes from being rigorously empirical and “untainted” by social and political debate (Weed and Mink 2002; Savitz et al. 1999). However, there are other social epidemiologists who work from the premise that the whole point of understanding the world is to change it and that one of the goals of social epidemiologic research is to foster change that would address the patterns of health inequality that their research reveals. These more public roles are, we argue, essential if social epidemiology is to contribute to the large, complex and multidimensional solutions that are required to address health inequality.

Arguably, there is more than enough room for both solution-focused KT and engaged scholarship (Committee on Institutional Cooperation 2005) within social epidemiology. For either approach to strengthen the impact of research evidence in reducing health inequities, however, a significant reconfiguration of the conventional KT account of policy change is required. As we have shown, social epidemiology addresses health and social policy problems that are more complex, more political and more value-laden than what has been described in the conventional KT literature. In this chapter we have aimed to outline what an alternative KT framework, one that is more appropriate for social epidemiology, might look like. Thus, in contrast to the boilerplate KT principles outlined above, which may only be useful from some types of social epidemiologic research, it would appear that social epidemiology also needs an approach to KT that:

-

Sees complex policy change in terms of processes, not decisions, and offers researchers a theory of policy change to help explain where, when and why research evidence may (or may not) play an influential role;

-

Acknowledges the importance of collective action in advancing social change and does not ignore the role of politics in policy making; and

-

Accommodates analyses of power and knowledge relationships and can illuminate roles for research to play in supporting, enriching and also challenging decision makers’ understanding of the “problem” of the social determinants of health.

7 Conclusions

At the outset we asked why social epidemiology research, in general, and health equity research, in particular, does not play a bigger role in promoting social change. We have tried to answer this question by examining some of the approaches for advancing research’s impact that are recommended in the health sciences literature and assessing the relevance of these KT tools for research focused on social determinants of health. Overall, we find that conventional KT is in several respects inadequate to the objectives of social epidemiology as a knowledge project. Drawing on the work of Jürgen Habermas, we have argued that conventional KT emphasizes an instrumental (i.e., problem-solving) role for research knowledge in society, while social epidemiology is characterized by its hermeneutical (i.e., explanatory) and emancipatory (i.e., equity-seeking) goals. These are fundamentally different approaches to research utilization and give rise to different approaches for bridging the gap between research and practice. This discussion allowed us to begin to develop an alternative KT framework that may be more appropriate for significant parts of the social epidemiology and health equity research agenda. This framework takes politics, power and values seriously in efforts to promote social change.

Abbreviations

- CIHR:

-

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- KT:

-

knowledge translation

- MMR:

-

measles, mumps and rubella

References

Asthana A, Halliday J (2006) What works in tackling health inequalities? Pathways, policies and practice through the lifecourse. The Polity Press, Bristol

Bacchi C (2008) The politics of research management: reflections on the gap between what we “know” and what we do. Health Soc Rev 17:165–176

Benoit C, Carroll D, Chaudhry M (2003) In search of a healing place: aboriginal women in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Soc Sci Med 56:821–833

Berkman L, Kawachi I (2000) Social epidemiology. Oxford University Press, New York

Bernal JD (1939) The social function of science. MIT Press, Cambridge

Bevir M, Rhodes R (2006) Governance stories. Routledge, New York

BiomedCentral (2010) About implementation science. http://www.implementationscience.com/info/about. Accessed 9 Aug 2010

Braveman P (2006) Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health 27:167–194

Burton P (2006) Modernising the policy process. Policy Stud 27:173–195

Buxton M, Hanney S, Jones T (2004) Estimating the economic value to societies of the impact of health research: a critical review. Bull World Health Organ 82:733–739

Carden F (2009) Knowledge to policy: making the most of development research. International Development Research Centre and Sage Publications, Ottawa/London

Chernomas R, Hudson I (2009) Social murder: the long-term effects of conservative economic policy. Int J Health Serv 39:107–121

Coburn D (2000) Income inequality, social cohesion and the health status of populations: the role of neo-liberalism. Soc Sci Med 51:135–146

Commission on Social Determinants of Health (2008) Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization, Geneva

Committee on Institutional Cooperation (2005) Resource guide and recommendations for defining and benchmarking engagement. CIC Committee on Engagement, Champaign

Daniels N (2008) Just health: meeting health needs fairly. Cambridge University Press, New York

Deleon P (1999) The stages approach to the policy process: what has it done? Where is it going? In: Sabatier P (ed) Theories of the policy process. Westview Press, Boulder

Dorfman L, Wallack L, Woodruff K (2005) More than a message: framing public health advocacy to change corporate practices. Health Educ Behav 32:320–336, Discussion 355–362

Dunn JR (2002) Housing and inequalities in health: s study of socioeconomic dimensions of housing and self reported health from a survey of Vancouver residents. J Epidemiol Community Health 56:671–681

Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group (1992) Evidence-based medicine. JAMA 268:2420–2425

Fafard P (2008) Evidence and healthy public policy: insights from health and political sciences. National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy. http://www.ccnpps.ca/docs/FafardEvidence08June.PDF. Accessed 8 Aug 2009

Frankish CJ, Hwang SW, Quantz D (2005) Homelessness and health in Canada: research lessons and priorities. Can J Public Health 96:S23–S29

Gagnon ML (2011) Moving knowledge to action through dissemination and exchange. J Clin Epidemiol 64:25–31

Graham H (2004) Social determinants and their unequal distribution: clarifying policy understandings. Milbank Q 82:101–124

Graham ID, Tetroe J (2007) How to translate health research knowledge into effective healthcare action. Healthc Q 10:20–22

Graham ID, Harrison MB, Cerniuk B et al (2007) A community-researcher alliance to improve chronic wound care. Healthc Policy 2:72–78

Habermas J (1971) Knowledge and human interests. Beacon Press, Boston

Helfand M, Buckley DI, Freeman M et al (2009) Emerging risk factors for coronary heart disease: a summary of systematic reviews conducted for the U.S. preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med 151:496–507

Howlett M, Ramesh M, Perl A (2009) Studying public policy: policy cycles & policy subsystems, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Don Mills

Kingdon JW (2003) Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Longman, New York

Krieger N (2001) A glossary for social epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health 55:693–700

Krieger N, Alegria M, Almeida-Filho J et al (2010) Who, and what, causes health inequities? Reflections on emerging debates from an exploratory Latin American/North American workshop. J Epidemiol Community Health 64:747–749

Lemieux-Charles L, Champagne F (eds) (2004) Using knowledge and evidence in health care: multidisciplinary perspectives. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Leone R, Carroll BW (2010) Decentralisation and devolution in Canadian social housing policy. Environ Plann C Gov Policy 28:389–404

Limoges C, Schwartzman S, Nowotny H et al (1994) The new production of knowledge: the dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. Sage Publications, London

Lomas J (2003) Health services research: more lessons from Kaiser Permanente and Veterans’ affairs healthcare system. BMJ 327:1301–1302

Lomas J, Fulop N, Gagnon D et al (2003) On being a good listener: setting priorities for applied health services research. Milbank Q 81:363–388

Merton RK (1973) The sociology of science: theoretical and empirical investigations. Chicago University Press, Chicago

Mosca L, Appel LJ, Benjamin EJ et al (2004) Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation 109:672–693

Murphy K, Topple R (eds) (2003) Measuring the gains from medical research an economic approach. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Murphy K, van der Meulen A (2008) What counts, who counts? Research, values, politics and the health of marginalized populations. In: Poster presented at The Summer Institute on KSTE Action, National Collaborating Centres for Public Health, Kelowna

Oakes JM, Kaufman JS (2006) Methods in social epidemiology. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Orsini M, Smith M (2010) Social movements, knowledge and public policy: the case of autism activism in Canada and the US. Crit Policy Stud 4:38–57

Pablos-Mendez A, Shademani R (2006) Knowledge translation in global health. J Contin Educ Health Prof 26:81–86

Raphael D (2003) Addressing the social determinants of health in Canada: bridging the gap between research findings and public policy. Policy Options/Politiques. www.irpp.org/po/archive/mar03/raphael.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov 2008

Rose H, Rose S (1970) Science and society. Penguin, Baltimore

Sabatier P, Jenkins-Smith H (1999) The advocacy coalition framework: an assessment. In: Sabatier PA (ed) Theories of the policy process. Westview Press, Boulder

Sackett DL, Strauss S, Richardson SR et al (2000) Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM, 2nd edn. Churchill Livingstone, London

Savitz DA, Poole C, Miller WC (1999) Reassessing the role of epidemiology in public health. Am J Public Health 89:1158–1161

Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham I (2009a) Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ 181:3–4

Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham I (eds) (2009b) Knowledge translation in health care: moving from evidence to practice. Wiley-Blackwell, Mississauga

Tibelius K, Stirling L (2007) Research capacity development and knowledge translation at CIHR. In: Presentation at the annual meeting of the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada, Victoria

Weed DL, Mink PJ (2002) Roles and responsibilities of epidemiologists. Ann Epidemiol 12:67–72

Weiss CH (1979) The many meanings of research utilization. Public Adm Rev 39:426–431

Wilkinson R, Pickett K (2009) The spirit level: why more equal societies almost always do better. Allen Lane, London

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Murphy, K., Fafard, P. (2012). Knowledge Translation and Social Epidemiology: Taking Power, Politics and Values Seriously. In: O’Campo, P., Dunn, J. (eds) Rethinking Social Epidemiology. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2138-8_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2138-8_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-2137-1

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-2138-8

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)