Abstract

Using highly disaggregated HS 8-digit product-category level data collected by the General Administration of Customs for 2000 and 2008, we comprehensively and systematically assess the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) exports of two types of manufactured goods (parts and components and final goods) as well as of nonmanufactured goods by different types of firms (foreign firms, domestic private firms, and domestic public firms). Our empirical framework is based on the gravity model, which we find works well for all specifications, and our results are largely consistent with economic intuition. All three different types of firms in the PRC export more to larger countries and less to countries that are farther away, irrespective of the type of product. Replacing the value of exports with the goods-extensive margin (i.e., number of goods) and goods-intensive margin (i.e., value of exports per good), the results again are largely consistent with economic intuition.

An earlier version of this chapter entitled “Different Types of Firms, Different Types of Products, Different Directions of Trade, and Their Dynamics: The Case of China” was presented at the 15th Korea Economic Association’s International Conference (June 2012), Asia-Pacific Trade Seminars 2012 Seminar (July 2012), and Korea and the World Economy XI Conference (July 2012). We are grateful to the participants for their useful comments and suggestions. Particularly, we are indebted to Sven Arndt, Bred Jensen, Fukunari Kimura, and Hankyung Sung for their useful comments. Part of the above paper was revised for PRC imports and has been published in China Economic Review (Lee, Park, and Wang 2013a), and this chapter is a revised version of the part for PRC exports.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has emerged as a global economic heavyweight since the late 1970s. The PRC’s phenomenal rise reflects its success in export-oriented manufacturing. International trade has been the main mechanism which transformed the PRC from a poor, isolated economy cut off from the rest of the world into a dynamic, open economy which plays a key role in the global economy. In the context of global trade, the PRC lies at the heart of global production networks which are based on cross-border flows of parts and components, culminating in their assembly into final products. Furthermore, foreign direct investment by multinational firms which produce different parts and components in different countries has further fueled global production networks and hence trade in parts and components.

According to evidence uncovered by Amighini (2012), the PRC rapidly expanded its market share of the global trade in information and communication technology (ICT) parts and components, and became one of the top three world exporters. Athukorala and Yamashita (2008) analyze the trade imbalance between the PRC and the United States (US) through the lens of global production sharing. Their in-depth analysis of the role of the two countries’ evolving roles in global production networks indicates that the US trade deficit is primarily a structural phenomenon which is the consequence of the PRC’s central role as the final assembly center of Factory Asia, or the regional production network of East and Southeast Asian countries which have collectively become a key manufacturing hub.

Examining trade flows between the PRC and its two largest trading partners, Japan and the US, Dean, Lovely, and Mora (2009) reveal that only a small share of these flows represent arm’s length, one-way trade in final goods. Instead, they found extensive two-way trade, deep vertical specialization, concentration of trade in computers and communication devices, and a prominent role of foreign-invested enterprises.

Analysis of East Asian export performance by Athukorala (2005, 2009, 2010) yields evidence of the PRC’s rise as a major player in global trade of machinery parts and/or components. Kim, Lee, and Park (2010) analyzed shifts in Asia’s global and regional trade ties. Their findings confirm the PRC’s central role as the assembly and production hub of fast-growing intra-Asian trade. Furthermore, the PRC’s share in the parts and components trade of the European Union (EU) and US is growing. This confirms the growing integration of East Asia’s production chains into the global business network.

Thus, despite the central role of the PRC in parts and components trade, most previous studies on the PRC’s components trade have been limited to a particular country or specific industries. Lee, Park, and Wang (2013b) provide a complete description of the PRC’s parts and components trade, as compared to its final goods trade, for the period 1992–2009. This chapter is an extension of our previous paper as regards the following two points:

-

(i)

While Lee, Park, and Wang (2013b) did not differentiate between different types of firms, we evaluate in this chapter how the PRC’s public firms, private firms, and foreign investment firms are different in PRC exports of parts and components.

-

(ii)

While Lee, Park, and Wang (2013b) considered only total exports of parts and components, we anatomize in this chapter PRC exports by examining (product and country) extensive and intensive margins of exports.

The examination of extensive and intensive margins of PRC exports is of particular interest as the focus of research on international trade has recently shifted from industries and countries to firms and products and a key implication of the firm heterogeneity theory is that extensive and intensive margins of international trade should be examined separately.Footnote 1 For example, the seminal theoretical model of Melitz (2003) shows that the extensive margin of the number of exporting firms should increase with the size of the destination market, since in larger markets firms of lower productivity can generate sufficient variable profits to cover the fixed costs of exporting. Bernard, Jensen, and Schott (2009) show empirically that in the case of the US, while the majority of the variation in flows across countries can be explained by the extensive margins of the number of firms and products, year-on-year changes in trade are mostly driven by the intensive margin of trade within continuing firm–product–country trade relationships.

The main objective of the present study is to assess comprehensively and systematically the PRC’s exports of parts and components conducted by different types of firms. For this purpose, as in Lee, Park, and Wang (2013a), this study uses the PRC’s export flows data collected by the General Administration of Customs of the PRC for 2 years: 2000 and 2008.Footnote 2 The database from the PRC Customs Administration includes the free on board (FOB) value of both exports and imports of the PRC for 243 destination and/or source economies and 7,526 different products at the 8-digit Harmonized System (HS) level. For each shipment, it also provides information on type of firm, transportation mode, customs office, and firm’s geographic information.

A similar approach is adopted by Lee, Park, and Wang (2013a), for the PRC’s imports of parts and components, pointing to its sheer size and explosive growth as well as its emergence as a globally influential importer in its own right. A number of recent empirical studies also use the Customs Administration database and other micro datasets to investigate the consequences of firm ownership on size, productivity, capital and skill intensity, and wages. For example, Lu, Yi, and Tao (2010) find that foreign affiliate exporters are less productive than nonexporters, while domestic exporters are more productive than nonexporters. Manova and Zhang (2009) find that, compared to private domestic firms, foreign-invested firms trade more and import more products from more source countries, but export fewer products to fewer destinations. Manova, Wei, and Zhang (2011) show that foreign-owned firms and joint ventures perform better than private domestic firms. Du et al. (2012) find that exporting delivered significant productivity gains for domestic firms but not for foreign affiliates. None of these studies, however, examine how trade in parts and components is different from trade in final goods.

2 Descriptive Statistics

In this section, we provide some descriptive statistics pertaining to the role of different types of firms and products in the PRC’s trade. Firms are categorized into three different types—domestic public firms, domestic private firms, and foreign-invested firms—in accordance with the Regulation of the People’s Republic of China on the Management of Registration of Corporate Enterprises.Footnote 3

2.1 Relative Shares of PRC Exports by Different Types of Firms

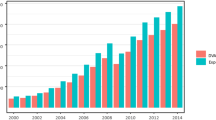

The changing pattern of PRC exports during the period 1993–2010 is shown in Fig. 5.1. Exports grew at a steady pace, except in 2009, when global trade shrank in the wake of the global financial crisis. Since joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in November 2001, the PRC has seen its trade grow exponentially. The PRC’s exports expanded 2.7 times between 1993 and 2000, from $92 billion to $249 billion. The growth accelerated between 2000 and 2008, when exports expanded 5.7 times from $249 billion in 2000 to $1,430 billion in 2008. During this period, foreign-invested firms, who entered during a massive wave of foreign direct investment inflows, accounted for the greater part of PRC exports.Footnote 4

Export shares of domestic and foreign-invested firms in the PRC ($ billion). PRC People’s Republic of China (Source: Government of the PRC, National Bureau of Statistics (2010))

Our analysis centers on PRC export data for 2000 and 2008. It should be noted that 2000 is the year before the PRC joined the WTO and 2008 is the year before global trade collapsed during the global crisis.

Table 5.1 is a summary of the relative shares of different firms in PRC exports. All goods are classified as either nonmanufactured goods (HS 01–27) or manufactured goods (HS 28–92). Manufactured goods are further classified as final goods and intermediate goods (i.e., parts and components). We define intermediate goods the same way as Athukorala (2010), who identifies a total of 525 6-digit manufactured goods HS codes (HS 28–96) as intermediate goods. One difference is that we exclude the 17 6-digit HS codes in HS 93–96 classified as “Others.”

Table 5.1 also shows that foreign firms accounted for the majority of total PRC exports in 2008. The share of foreign firms stood at 55.4 % of total exports in 2008, up from 48.0 % in 2000. The dominance of foreign firms is more visible in the exports of manufactured goods. In 2008, the share of foreign firms in PRC manufactured exports stood at 56.6 %. In the context of manufactured exports, the dominance of foreign firms is even more pronounced for intermediate goods. In 2008, foreign firms accounted for 69.6 % of PRC intermediate goods exports.

Turning to exports by PRC domestic firms, the share of public and private firms in total exports was roughly the same at around 22 % each.Footnote 5 The exports of parts and components follow a similar pattern, with both public and private firms accounting for about 15 % of total exports in 2008.

Going forward, however, private firms are expected to play a much larger role in PRC exports and imports, regardless of the kind of product. Recent history attests to the explosive rise of private firms in PRC trade. More specifically, the export share of private firms shot up from 1.0 % to 22.8 % between 2000 and 2008, and their import share from 0.6 % to 11.0 %. There was a correspondingly sharp decline in the shares of public firms.Footnote 6

2.2 Major Destinations for PRC Exports of Parts and Components

Table 5.2 shows the shares of major partners for PRC exports of parts and components for different types of firms. As noted earlier, foreign-invested firms took the lion’s share of the PRC’s global exports of parts and components. Another notable aspect is that Hong Kong, China was the major destination for PRC exports of intermediate goods in 2008, accounting for 22.2 %, followed by the EU-15 and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) countries which accounted for 17.7 % and 17.4 %, respectively.Footnote 7

Table 5.3 shows that PRC exports of parts and components are highly concentrated in general machinery (HS 84) and electric machinery (HS 85).

2.3 Extensive and Intensive Margins

As noted, many researchers in the literature of firm heterogeneity in international trade have examined different types of extensive and intensive margins of international trade. A lot of studies looked at the firm-extensive margin of trade, but recent studies have analyzed goods-extensive margins and country-extensive margins. In this chapter, we first analyze the PRC’s goods-extensive and -intensive margins and do likewise for country-extensive and -intensive margins.

We can decompose bilateral exports T ij from country i to country j into:

where N ij is the goods-extensive margin of the number of product observations with positive exports and A ij is the goods-intensive margin of average product exports.

Therefore, the PRC’s total world exports T can be decomposed into:

where N is the goods-extensive margin of the number of product observations with positive exports and A is the goods-intensive margin of average product exports.

Table 5.4 provides a summary of the goods-extensive and -intensive margins of PRC exports for different types of firms. The goods-extensive margin is defined as the number of HS 8-digit classification codes with positive exports.Footnote 8 As panel B shows, for final goods, the goods-extensive margin rose between 2000 and 2008 for all types of firms. The exports of private firms grew by over 100 %.Footnote 9 In contrast, for intermediate goods, goods-extensive margin exports of domestic public firms and foreign-invested firms declined while the exports of private firms rose by over 50 %. In 2008, for exports of both final and intermediate goods, the goods-extensive margin was similar among all three types of firms.

The goods-intensive margin, the amount of total exports divided by the goods-extensive margin, is reported in panel C. The goods-intensive margin grew at an exceptional pace between 2000 and 2008, for all types of firms. Strikingly, the goods-intensive margin of domestic private firms expanded by over 10,000 %. Even so, in 2008 the goods-intensive margin remained the highest for foreign-invested firms.

The PRC’s exports to the world T can also be decomposed into:

where M is the country-extensive margin of the number of partner countries and B is the country-intensive margin of average exports to a partner country conditional on positive trade.

Panel B in Table 5.5 reports the country-extensive and -intensive margins of PRC exports for different types of firms. For all types of goods and firms, the country-extensive margin increased for exports. It is especially noteworthy that the country-extensive margin increased most rapidly for private firms’ exports of intermediate goods.

A comparison of Tables 5.1, 5.4, and 5.5 indicates that between 2000 and 2008 expansion of PRC exports of manufactured goods were fueled by expansion in the intensive margin of exports of a given good (i.e., goods-intensive margin) and for a given country (country-intensive margin) and by the extensive margin of the number of exported goods (i.e., goods-extensive margin). On the other hand, the extensive margin of the number of countries (i.e., country-extensive margin) did not contribute to export growth.Footnote 10 In 2008, the country-extensive margin is comparable for foreign and domestic firms, while the country-intensive margin is greater for foreign firms.Footnote 11

3 Empirical Models of Parts and Components Trade by Different Types of Firms

In this section, we present the empirical framework we use to estimate trade in intermediate goods.

3.1 The Basic Model

As noted, we use the gravity equation to assess how the three different types firms behave differently with respect to choosing their export destinations depending on different product types.Footnote 12 Though the gravity model is commonly used in estimating the pattern of international trade, estimating the log-linearized equation by ordinary least squares (OLS) might lead to biases when the presence of heteroskedacity is severe. This has been argued in Santos Silva and Tenreyro (2006), who suggest as an alternative that the gravity model be estimated in its multiplicative form and use a Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood (PPML) estimator that is usually used for count data. A desirable property of PPML is that a Poisson estimator naturally includes observations for which the observed value is zero, while such observations are dropped from the OLS model because the logarithm of zero is undefined. Therefore, we estimate a multiplicative form model using the PPML estimator to obtain the following standard gravity equationFootnote 13:

where

- T jt :

-

= export flows from the PRC to country j at time t

- LnGDP j :

-

= natural logarithm of gross domestic product (GDP) of country j at time t

- LnDIST j :

-

= natural logarithm of geographical distance between the PRC and country j

- LnREMOTE i :

-

= natural logarithm of remoteness of country j at time t

= log(1/∑ k (GDP k /GDP w )/ DISTANCE jk ), where GDP w = world GDP

- ISLAND j :

-

= 1 if country j is an island country, 0 otherwise

- LANDLOCKED j :

-

= 1 if country j is a landlocked country, 0 otherwise

- RTA jt :

-

= 1 if country j is the PRC’s regional trade agreement (RTA) partner at time t, 0 otherwise.

- WTO jt :

-

= 1 if country j is a WTO member at time t, 0 otherwise

- FTI jt :

-

= free trade index of country j at time t

- ε t :

-

= year dummy

- ε ij :

-

= random disturbance term

In Eq (5.1), we also augment dummy variable for six different groups such as Hong Kong, China and Taipei,China,Footnote 14 Japan, the Republic of Korea, ASEAN-6 member countries (Association of Southeast Asian Nations excluding CLMVFootnote 15), EU-15 member countries,Footnote 16 and NAFTA member countries so as to identify any region-specific effects in PRC exports of different types of products by different types of firms. Examining the region-specific effects is interesting because many studies have found that the PRC’s increasing integration into the world economy has been coupled with its increasing role in fragmentation of production among Asian countries and in parts and components trade.

Among the explanatory variables, gross domestic product (GDP, in US dollars), GDP per capita, population, and area (in square kilometers) are taken from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators Online data.Footnote 17 Geographical distance is taken from the website of Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales (CEPII).Footnote 18 It is noted that the distances are weighted distances, which use city-level data to assess the geographic distribution of the population inside each country. The remoteness index is also calculated using the weighted distances. The variables indicating whether the country is landlocked or an island are also taken from the CEPII data. Finally, information on the WTO members is taken from the WTO website and information on the PRC’s regional trade agreements (RTAs) from the PRC Ministry of Commerce’s “China FTA Network” website.Footnote 19 The FTI index is from the Freedom to Trade Internationally data of the Economic Freedom of the World report by the Fraser Institute.

As discussed, PRC exports (T j ) can be decomposed into the goods-extensive margin of the number of product observations with positive exports (N j ) and the goods-intensive margin of average product exports conditional on positive trade (A j ). Therefore, N j and A j are also regressed, alternatively, against the regressors in the gravity equation presented in Eq (5.1).

Our benchmark model of the gravity equation is static with a year dummy, as our data are based on 2 years—2000 and 2008—and country fixed effects cannot be estimated.

4 Empirical Results

In this section, we report and discuss the main empirical results.

4.1 The Basic Model

Table 5.6 shows our benchmark regression results of the static gravity model in which the dependent variable is the value of export flows to each destination country for each category of product (i.e., final products and intermediate inputs), from the three different types of firms—public, private, and foreign.

The gravity model works well for all equations, as indicated by the large size of R2. All three different types of firms in the PRC export more to larger countries and less to more distant countries, irrespective of the types of products. We find, however, that public and private firms in the PRC export more to countries that are farther away from most other countries in the world, which is inconsistent with our prediction. All three types of firms appear to export less to landlocked and to island countries. The PRC’s public firms export more of both final and intermediate goods to the PRC’s RTA partners, but other types of firms are not responsive to the RTA membership of export destinations. This is not surprising because in our sample, there was no RTA partner of the PRC in 2000 and only a few countries became RTA partners of the PRC between 2000 and 2008.Footnote 20 However, one should not place too much confidence in such estimates, because without taking full advantage of the panel data with country pair fixed effects (partner country effects in our case) or with first differences, our regression cannot accurately estimate the precise impact of free trade agreements (FTAs), as explained by Baier and Bergstrand (2007) and Baier, Bergstrand, and Feng (2011). It is also found that none of the firms in the PRC export more to WTO member countries, irrespective of type of goods. It is also interesting to note that the PRC exports more to countries with a higher degree of free trade, measured by the Frasier Institute’s Freedom to Trade Internationally index.

Table 5.7 reports the regression results with the dependent variable replaced with the goods-extensive margin of PRC exports and Table 5.8 reports the results when the dependent variable is the goods-intensive margin of PRC exports.

For both the extensive and intensive margins of PRC exports, the GDP of partners is positive and significant. Thus, the PRC exports more to large economies because it (i) exports larger quantities of a given good (intensive margin) to large economies and (ii) exports a wider set of goods (extensive margin) to large economies. Our finding is consistent with Eaton, Kortum, and Kramarz (2004, 2011) who show that the number of firms and products selling to a market increases with market size, and also with Bernard, Redding, and Schott (2011b) who show that the average exports per firm and product increase with market size.

For both the extensive and intensive margins, the distance variable is significant and negative. However, the absolute size of these coefficients is smaller for extensive margins than for intensive margins, irrespective of the type of goods and the type of firm. This is in contrast with the findings of Bernard, Redding, and Schott (2011b) that the negative effect of distance on aggregate bilateral trade is largely accounted for by the extensive margin of the number of heterogeneous firms and products participating in trade, rather than the intensive margin of the amount traded per firm and product. It is also interesting to note that the free trade index also carries positive and significant coefficients in all equations for both the extensive margin and intensive margin of PRC exports.

4.2 Summary of Region-Specific Effects of PRC Exports

Tables 5.6, 5.7 and 5.8 also report the estimates for region dummies. They are summarized in Table 5.9. One of the major noticeable findings is that among the six different groups, Hong Kong, China; Taipei,China; and NAFTA appear to be the leading major destinations for PRC exports. In contrast, among the three different East Asian groups, only the coefficient for the Japan dummy carries a positive and significant coefficient for total value and its intensive margin for exports of parts and components conducted by foreign-invested firms. This suggests that the PRC’s global supply chain does not have any special connection with East Asian economies, except for Hong Kong, China and Taipei,China. This is somewhat surprising given the PRC’s central role in East Asian production networks.

5 Concluding Observations

The PRC’s phenomenal rise as a global economic heavyweight was driven by its integration into the world economy. In particular, the explosive growth of its trade and exports since its market-oriented reforms in 1978 contributed to its sustained rapid growth. The big catalyst behind the PRC’s export-oriented industrialization was foreign direct investment, which provided the capital and technology to build up a globally competitive manufacturing base within a short period of time. Multinational corporations typically locate different parts of their production process in different countries, and account for a large part of global parts and components trade. The PRC is still in the midst of a transition toward a market economy, during which a large mass of public firms coexists with a growing mass of public firms. In short, PRC exports are heterogeneous in terms of both trading firms and traded products. Therefore, a more complete analysis of the PRC’s trade would be incomplete without taking into account firm and product heterogeneity.

Our empirical analysis based on the gravity model of trade yields a number of interesting findings which are largely consistent with economic intuition. For example, we find that all three types of PRC firms—foreign, domestic public, and domestic private—export more to larger economies and less to more distant economies, for both final goods and intermediate goods. The export behavior of different types of firms may well be similar but nonetheless, given the very different nature of the three types of firms, distinguishing among them rather than lumping together seems much more sensible. Likewise, given the very different nature of final versus intermediate goods, investigating their export behavior separately would allow for a much richer and more meaningful analysis. We hope with this study to lay the foundation for more in-depth analysis that fully captures the rich diversity of the PRC’s exports.

Notes

- 1.

Bernard et al. (2011a) provide a comprehensive survey.

- 2.

- 3.

See Government of the People’s Republic of China, National Bureau of Statistics (2010). Public firms are further categorized into two groups: state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and collectively owned enterprises. SOEs refer to business entities whose entire assets are owned by the state. Collectively owned enterprises refer to business entities whose assets are owned collectively by a town or a group of people. Private firms are also further categorized into two types: A sole proprietorship company is solely invested by a natural person whereas a joint stock company is a company whose capital is divided into shares. Foreign-invested firms can be categorized into three types: Sino-foreign cooperative enterprises, Sino-foreign joint ventures, and foreign-funded firms. In Sino-foreign cooperative enterprises, the foreign party typically supplies all or most of the capital and technologies, while the PRC party supplies land, factory buildings, and useful facilities. In Sino-foreign joint ventures, foreign companies or individuals and PRC companies or individuals typically invest together, operate together, take risk according to the ratio of their capital, and jointly take responsibility for their profits and losses. Foreign-funded firms can be either wholly foreign-owned enterprises which are exclusively invested by foreign companies or foreign-funded shareholding companies which are shareholding companies partially funded by foreign companies or individuals.

- 4.

This pattern is also similar for PRC exports. See Lee, Park, and Wang (2013b).

- 5.

The role of public firms, however, is much larger than the role of private firms in PRC imports. See Lee, Park, and Wang (2013a).

- 6.

Since the PRC began accelerating the reform of state-owned enterprises in 2003, many inefficient small SOEs have gone bankrupt, while the private enterprises have increased rapidly.

- 7.

This is in consistent with Feenstra and Hanson (2004) who find that Hong Kong, China distributes a large fraction of PRC exports.

- 8.

Hummels and Klenow (2005) define each good as a 6-digit Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) category to decompose total trade into the “goods” margin of trade. In contrast, Hillberry and C. McDaniel (2002) and Kehoe and Ruhl (2009) decompose post-NAFTA trade among the participating members into goods-extensive and -intensive margins using 4-digit SITC data. In their gravity study on the relationship between economic integration agreements and the margins of international trade, Baier, Bergstrand, and Feng (2011) also use 4-digit SITC classification to decompose bilateral trade between 149 countries. In contrast, each good is defined in this chapter as a 8-digit HS category, the most disaggregated category, compared with other studies.

- 9.

A similar pattern is also found for PRC imports. See Lee, Park, and Wang (2013a).

- 10.

A similar pattern is also found for PRC imports. See Lee, Park, and Wang (2013a).

- 11.

In the case of PRC imports, the country-extensive margin (i.e., the number of source countries) is greater for foreign-invested firms than for domestic public or private firms and the country-intensive margin (i.e., the average imported value from a given country) is also greater for foreign firms than for domestic firms. See Lee, Park, and Wang (2013a).

- 12.

Since Tinbergen (1962) and Pöyhönen (1963), the simple gravity equation has proved highly successful in empirical analysis. Researchers have recently shown that the gravity equation can be derived from many different models of international trade (Helpman and Krugman 1985; Bergstrand 1989; Deardorff 1998; Evenett and Keller 1998; Eaton and Kortum 2002). In addition, researchers such as Anderson and van Wincoop (2003) have shown that bilateral trade depends not only on country size and distance, but also on relative distance (i.e., multilateral price terms).

- 13.

We also estimated the OLS model and found similar results.

- 14.

Hong Kong, China and Taipei,China are grouped as one region because the PRC shares a number of commonalities with them, such as language and culture, and they maintain a special relationship.

- 15.

Cambodia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, and Viet Nam.

- 16.

The original 15 member countries of the EU.

- 17.

- 18.

- 19.

- 20.

In our sample, ASEAN (July 2005), Pakistan (July 2007), Chile (October 2006), and New Zealand (October 2008) are the only economies which became RTA partners of the PRC between 2000 and 2008. Dates in parenthesis are the dates when the agreement entered into force.

References

Amighini, A.A. 2012. China and India in the international fragmentation of automobile production. China Economic Review 23(2): 325–341.

Anderson, J.E., and E. van Wincoop. 2003. Gravity with gravitas: A solution to the border puzzle. American Economic Review 93(1): 170–192.

Athukorala, P. 2005. Product fragmentation and trade patterns in East Asia. Asian Economic Papers 4(3): 1–27.

Athukorala, P. 2009. Production networks and trade patterns: East Asia in a global context. Departmental working papers, 2009–15. Canberra: Australian National University, Economics Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies.

Athukorala, P. 2010. Production networks and trade patterns in East Asia: regionalization or globalization? ADB working paper no. 56. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Athukorala, P., and N. Yamashita. 2008. Global production sharing and US–China trade relations, China’s dilemma: Economic growth. In China’s dilemma, economic growth, the environment and climate change, ed. L. Song and W.T. Woo, 59–89. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

Baier, S.L., and J.H. Bergstrand. 2007. Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade? Journal of International Economics 71(1): 72–95.

Baier, S.L., J.H. Bergstrand, and M. Feng. 2011. Economic integration agreements and the margins of international trade. Unpublished manuscript.

Bergstrand, J.H. 1989. The generalized gravity equation, monopolistic competition, and the factor-proportions theory in international trade. Review of Economics and Statistics 71(1): 143–153.

Bernard, A.B., J.B. Jensen, and P.K. Schott. 2009. Importers, exporters and multinationals: A portrait of firms in the US that trade goods. In Producer dynamics: New evidence from micro data, ed. T. Dunne, J.B. Jensen, and M.J. Roberts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bernard, A.B., J.B. Jensen, S.J. Redding, and P.K. Schott. 2011a. The empirics of firm heterogeneity and international trade, NBER working paper no. 17627. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bernard, A.B., S.J. Redding, and P.K. Schott. 2011b. Multi-product firms and trade liberalization. Quarterly Journal of Economics 126(3): 1271–1318.

Dean, J.M., M.E. Lovely, and J. Mora. 2009. Decomposing China-Japan-U.S. trade: Vertical specialization, ownership, and organizational form. Journal of Asian Economics 20(6): 596–610.

Deardorff, A.V. 1998. Determinants of bilateral trade: Does gravity work in a neoclassic world? In The regionalization of economy, ed. J.A. Frankel. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Du, J., Y. Lu, Z. Tao, and L. Yu. 2012. Do domestic and foreign exporters differ in learning by exporting? Evidence from China. China Economic Review 23(2): 296–315.

Eaton, J., and S. Kortum. 2002. Technology, geography, and trade. Econometrica 70(5): 1741–1779.

Eaton, J., S. Kortum, and F. Kramarz. 2004. Dissecting trade: Firms, industries, and export destinations. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 94(2): 150–154.

Eaton, J., S. Kortum, and F. Kramarz. 2011. An anatomy of international trade: Evidence from French firms. Econometrica 79(5): 1453–1498.

Evenett, S.J., and W. Keller. 1998. On theories explaining the success of the gravity equation, NBER working paper no. 6925. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Feenstra, R., and G. Hanson. 2004. Intermediaries in entrepôt trade. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 13(1): 3–35.

Government of the People’s Republic of China, National Bureau of Statistics. 2010. China statistical yearbook. Beijing: China Statistics.

Helpman, E., and P.R. Krugman. 1985. Market structure and foreign trade. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hillberry, R., and C. McDaniel. 2002. A decomposition of North American trade growth since NAFTA. United States International Trade Commission working paper 2002-12-A.

Hummels, D., and P.J. Klenow. 2005. The variety and quality of a nation’s exports. American Economic Review 95(3): 704–723.

Kehoe, T.J., and K.J. Ruhl. 2009. How important is the new goods margin in international trade? Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Staff Report 324.

Kim, S., J.-W. Lee, and C.-Y. Park. 2010. The ties that bind Asia, Europe, and United States, ADB economics working paper series no. 192. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Lee, H.-H., D. Park, and J. Wang. 2013a. Different types of firms, different types of products, and their dynamics: An anatomy of China’s imports. China Economic Review 25(C): 62–77.

Lee, H.-H., D. Park, and J. Wang. 2013b. The role of China in international fragmentation and production network: An empirical investigation. Korea and the World Economy 14(2): 1–32.

Lu, J., L. Yi, and Z. Tao. 2010. Exporting behavior of foreign affiliates: Theory and evidence. Journal of International Economics 81(2): 197–205.

Manova, K., and Z. Zhang. 2009. China’s exporters and importers: Firms, products and trade partners, NBER working paper no. 15249. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Manova, K., S.-J. Wei, and Z. Zhang. 2011. Firm exporters and multinational activity under credit constraints, NBER working paper no. 16905. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Melitz, M.J. 2003. The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71(6): 1695–1725.

Pöyhönen, P. 1963. A tentative model for the volume of trade between countries. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 90: 93–100.

Santos Silva, J.M.C., and S. Tenreyro. 2006. The log of gravity. Review of Economics and Statistics 88(4): 641–658.

Tinbergen, J. 1962. Shaping the world economy. New York: Twentieth Century Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Asian Development Bank Institute

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lee, HH., Park, D., Wang, J. (2016). Exports of Parts and Components by Different Types of Firms in the People’s Republic of China: A Comprehensive Examination. In: Wignaraja, G. (eds) Production Networks and Enterprises in East Asia. ADB Institute Series on Development Economics. Springer, Tokyo. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55498-1_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55498-1_5

Publisher Name: Springer, Tokyo

Print ISBN: 978-4-431-55497-4

Online ISBN: 978-4-431-55498-1

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)