Abstract

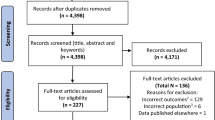

Neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as hallucinations, are common in neurodegenerative disorders and primarily in Parkinson’s disease, where they contribute significantly to disease morbidity and caregiver burden, eventually leading to early nursing home placement. As the average life expectancy in developed nations continues on an upward trend, the incidence of neurodegenerative disease and their neuropsychiatric complications follows in parallel. This review provides an overview of synucleinopathies, tauopathies, prion diseases, and heredodegenerative disorders in which visual hallucinations (VH) are present. Epidemiological information along with factors associated with symptom presentation is outlined. The clinical characteristics of visual disturbances and their impact on disease management are discussed. Relevant treatment options for VH in each neurodegenerative syndrome are also reviewed.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Dementia with Lewy bodies

- Neurodegenerative disorders

- Parkinson’s disease

- Visual hallucinations

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by progressive decline in the structure, activity, and function of the central nervous system. Neuronal dropout usually results in disruption of multiple pathways, regional neurotransmitter deficits, and neurochemical imbalance. As a result, distinctive phenotypic expressions are grouped into disease clinicopathological entities [Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), etc.]. Clinicians recognize this distinctive set of progressive signs and symptoms and, on pathological examination, the pathologist reports lesions in brain regions that underpin these signs and symptoms.

Neuropsychiatric manifestations are very prevalent and an integral part of the symptom/sign pattern of neurodegenerative diseases. Most importantly, they significantly add to disease morbidity, caregiver burden, and deteriorating health-related quality of life. Although the mechanism remains unknown, it is hypothesized that neuropsychiatric symptoms may be primary and an integral part of the neurodegenerative process, secondary to medication or comorbid conditions affecting the dysregulated and susceptible system, or simply reactive phenomena.

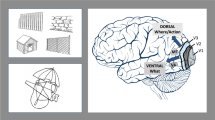

The pattern recognition approach to disease has been palliative, and there has been no knowledge of the causes of the damage. Advances in molecular genetics and immune-based histopathology techniques have allowed a classification system of neurodegenerative diseases based on protein accumulation. Microtubule-associated tau is one protein that has important functions in healthy neurons but which forms insoluble deposits in diseases now known collectively as tauopathies. Tauopathies encompass more than 20 clinicopathological entities, including AD, the most common tauopathy, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), corticobasal degeneration, and postencephalitic parkinsonism. The term synucleinopathies refers to a certain subset of neurodegenerative diseases with a similar pathological lesion pattern consisting of insoluble alpha-synuclein in selected neuronal and glial cells. Accumulation of alpha-synuclein is seen in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), PD, and multiple systems atrophy (MSA). A smaller subset of neurodegenerative diseases is genetically determined and can be collectively grouped into the heredodegenerative category. This review focuses on one of the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms in neurodegenerative disorders: the characteristics, etiology, and treatment of visual hallucinations (VH) are discussed in the most common neurodegenerative disorders.

Visual Hallucinations in Synucleinopathies

Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Epidemiology

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is frequently recognized as the second most common degenerative dementia [1]. Although extensive epidemiological literature is lacking, a recent review indicates that prevalence estimates for DLB range from 0.1% to 5.0% in the general population and from 1.7% and 30.5% in dementia cases [1]. In accordance with current consensus criteria, recurrent VH are among the core features indicative of DLB [2]. Approximately two-thirds of patients with DLB present with VH [3, 4]. Patients with DLB commonly present with hallucinations, and nearly half have hallucinations within 2 years after the first clinical symptom [5].

Factors Associated with VH in DLB

A recent community-based autopsy study found that cases with VH were more likely than cases without VH to have Lewy-related pathology (78% versus 45%) [6]. Overall cortical Lewy body (LB) burden is greater in cases with early VH (at onset or within the first 2 years of the disease course), which relates to more LBs in the inferior temporal cortices [5]. Additional neuropathological evidence indicates that VH are associated with more LB pathology in the parahippocampus and amygdala [5].

Neuroimaging technologies are also used to elucidate factors associated with VH. Although most effort focuses on identifying imaging markers that differentiate DLB from other dementing disorders, some investigations examine potential mechanisms related specifically to VH in DLB. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET) evaluations show that people living with DLB and VH have relative metabolic reductions in the right temporo-occipital junction and the right middle frontal gyrus compared to those with DLB without VH [7].

Certain clinical characteristics are also associated with VH in DLB. The Consortium on DLB [8] reports that VH may particularly present during periods of diminished consciousness. Visual impairment exacerbates VH; this is likely a consequence of selective sensory deprivation, and an increase in environmental stimulation may provide temporary relief [8]. People living with DLB and VH perform worse on overlapping figure identification compared to those without VH [9]. Additional evidence shows that DLB and demented PD patients with recurrent VH are significantly more impaired in visual discrimination, space-motion perception, and object-form perception than patients without VH [10].

Clinical Characteristics of VH in DLB

While people living with DLB have hallucinatory experiences that encompass a variety of modalities, VH are most common [4]. These VH are frequently complex, occur at least once a day, last for minutes, and consist of a single, colored, stationary object in the central visual field [11]. The experiences are often benign and not perceived as threatening. However, there are exceptions. These characteristics are largely similar to those evidenced in PD dementia. Specific phenomenological characteristics of VH in DLB include anonymous people/soldiers; body parts; animals; friends and family; children/babies; and machines [11]. VH in DLB tend to persist and are stable over time [12].

Clinical Impact and Treatment of VH in DLB

VH are considered one of the most important neuropsychiatric targets for intervention in DLB [13]. Several pharmacological intervention strategies show some success in the treatment of hallucinations in DLB. Deficits in cortical acetylcholine are associated with VH [14] and thus, unsurprisingly, VH are often responsive to pharmacotherapies with anticholinesterase properties. DLB patients with VH who are cognitive responders to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine show greater improvement than responders without VH [15]. Furthermore, cognitive nonresponders with VH show less cognitive decline at follow-up than do cognitive nonresponders without VH [15]. Although these medications were originally created to treat AD, evidence shows a better response in the treatment of DLB than AD [16]. Because of the potential for severe adverse reactions to neuroleptics [2, 17], the use of antipsychotics in the treatment of DLB should only be initiated after careful consideration.

Parkinson’s Disease

Epidemiology

Worldwide prevalence rates of Parkinson’s disease (PD) tend to vary widely [18]. Estimates of the number of people living with PD in the world’s ten most populous nations, along with Western Europe’s five most populous nations, range between 4.1 and 4.6 million [19]. This number is expected to double to somewhere between 8.7 and 9.3 million by 2030. Annual incidence ranges between 4.9 and 26 per 100,000 [20]. Hallucinations occur in 20% to 40% of PD patients receiving symptomatic therapy [21], although as many as 75% of patients develop hallucinatory phenomena of a visual nature [22]. VH in PD are often considered treatment related because prevalence rates in the pre-levodopa era were as low as 5% [23, 24].

Factors Associated with the Presentation of Hallucinations in PD

Longer PD disease duration, higher unified PD rating scale (UPDRS) total score, and dementia show independent associations with the occurrence of medication-induced VH in PD [25]. All dopaminergic therapies (direct, through receptor stimulation, or indirect, through metabolic enzyme inhibition), and especially dopamine agonist therapy, can elicit hallucinations and psychosis [26]. Additionally, numerous studies find greater prevalence of hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms in demented versus nondemented patients with PD [27]. VH are present in 70% of PD patients with dementia [28]. Approximately 45% of nondemented PD patients with VH go on to develop dementia within a year [29]. Additional evidence suggests that deficient performance on cognitive tasks, such as verbal fluency, predicts the development of hallucinations in people living with PD [30]. Furthermore, REM (rapid eye movement) sleep behavior disorder comorbidity is associated with increased VH risk in PD.

Clinical Characteristics of VH in PD

The VH most often reported in PD are drug induced, complex, and consist of animate or inanimate objects or persons [31]. However, perceptual phenomena that are more transient and less clear can also occur [28]. VH typically appear several years after disease onset and usually contain five or fewer images, which are sometimes meaningful to the patient. The typical “hallucinator’s experience” [32] occurs while alert and with eyes open, in dim surroundings. The hallucination is present for a few seconds and then suddenly vanishes. Initially, hallucinations are “friendly.” Patients often see fragmented figures of beloved familiar persons or animals. As reality testing and insight further decrease, the content of the hallucinations may change to frightening images (e.g., insects, rats), inducing anxiety and panic attacks [33]. Hallucinations may become malignant, disabling, and intermingled with paranoid patterns, including suspiciousness, negativism, and sexual accusations. Ideas of persecution, fearfulness, agitation, aggression, confusion, and delirium become commonplace. It is at this point that the situation at home often becomes unbearable, and the patient is frequently placed in a nursing home [34]. Although VH are predominant, auditory hallucinations (mixed with visual) are reported to affect about 10% of patients [28].

Clinical Impact and Treatment of VH in PD

Without intervention, hallucinations with retained insight can evolve to malignant hallucinations without insight [35]. Presence of hallucinations can predict nursing home placement [36] and may predict mortality in PD [37]. When hallucinations first present, a systematic evaluation for potential causes should ensue. Once factors such as secondary illness or medication overdose are ruled out, the physician should revisit the diagnosis of PD to ensure premorbid psychosis or other neurodegenerative diseases do not explain the VH.

As a first-line treatment, visual, cognitive, and interactional coping strategies [38], along with appropriate sleep hygiene, should be encouraged. If these strategies do not effectively resolve the VH, removal or taper of medications with the lowest antiparkinsonian effect may be useful. Adjustment of dopaminergic therapy to balance the treatment of motor and nonmotor symptoms such as VH is perhaps the most effective treatment strategy. Although some evidence suggests that treatment with antipsychotics may delay psychiatric deterioration [39], the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has determined that atypical antipsychotic use may contribute to increased mortality in elderly dementia patients [40]. Additional evidence linking antipsychotic use to increased risk of pneumonia is particularly relevant to treatment considerations, as pneumonia is the most commonly reported cause of death in PD [41]. Although clozapine is considered “probably effective” and quetiapine is considered “possibly effective” in the treatment of psychosis in PD [42], caution must be used when using antipsychotics “off-label” to treat hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms in PD. Pimavanserin tartrate, a selective 5-HT2A inverse agonist, has shown encouraging efficacy against psychotic symptoms in PD in phase II and is currently being tested in phase III pivotal trials [43]. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors may also have potential utility in the treatment of VH in PD. A case report indicates donepezil may decrease VH in PD [44], and PD patients with VH may show greater benefit from rivastigmine than those without VH [45]. However, no large, controlled trials have been conducted to determine the efficacy of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of VH in PD.

Multiple System Atrophy

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder with a diverse clinical presentation that can include parkinsonism, autonomic failure, urogenital dysfunction, cerebellar ataxia, and corticospinal disorders [46]. Prevalence estimates range from 1.9/100,000 to 4.9/100,000 per year, with an estimated incidence of 0.6/100,000 per year [47]. Nonmedication-induced hallucinations are considered nonsupportive of MSA diagnosis [46]. Nonetheless, evidence from case reports suggests that VH occur in up to 9.5% of pathologically confirmed MSA cases [48]. VH reported in a study by Papapetropoulos and colleagues consisted of small and friendly animals in one case not receiving dopaminergic therapy and fragmented friendly faces in dimly lit surroundings related to levodopa in another case. Neither case required treatment with antipsychotics [48].

VH in Tauopathies

Alzheimer’s Disease

Epidemiology

AD is the most common degenerative dementia. There were 4.5 million people living with AD in the United States in 2000; this number is expected to nearly triple by 2050 [49]. A population-based European study estimates the age-standardized prevalence of AD to be 4.4%, with prevalence increasing with age [50]. Nearly 19% of patients with AD experience VH [51]. Data on persistence of psychotic symptoms, including VH, in AD are mixed, and methodological differences likely contribute to disparate findings.

Factors Associated with the Presentation of Hallucinations in AD

The severity of cognitive impairment in AD often relates to prevalence of hallucinations, with more impaired patients being at higher risk for hallucinations [51]. Several studies show that African Americans have a higher risk of developing hallucinations than Caucasians; however, this relationship appears to be more relevant in advanced disease stages. Data on other clinicodemographic factors are either mixed or equivocal and are discussed more fully by Ropacki and Jeste [51]. Additional evidence indicates that patients with dementia (including, but not limited to AD) and hallucinations are more likely to present with agitation, delusions, and apathy than those without hallucinations [6]. This cohort of hallucinators was also more likely to have Lewy-related pathology upon autopsy.

Clinical Characteristics of VH in AD

Assessing VH in people living with AD and other cognitive disorders is frequently challenging. Some studies rely on caregiver reports to identify patients experiencing VH, whereas others do not often report characteristics of the hallucinations other than prevalence or Neuropsychiatric Inventory score. Some work shows that VH in AD include images of familiar people, dead relatives, animals, and machinery [52]. Other work shows that 54% of AD patients with VH also experience an auditory component [53]. Because of the clinical presentation of AD, VH may not be adequately captured with common methodologies.

Clinical Impact and Treatment of VH in AD

Hallucinations in AD have been associated with aggressive behavior, verbal outbursts, asocial behavior, and falls; however, other studies have failed to show these relationships [54]. The presence of hallucinations predicts increased risk for cognitive/functional decline, institutionalization, and mortality in AD [55]. At present, regulatory authorities including the FDA have yet to approve any pharmacotherapeutic agent for the treatment of dementia-related psychosis. Consequently, as with previously mentioned disorders, nonpharmacological management is the recommended first-line treatment. Although some atypical antipsychotics may be modestly effective treatments for psychosis in AD, adverse event and mortality risk may significantly outweigh the treatment benefits in this population [17, 40, 56].

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a phenotypically heterogeneous, progressive neurodegenerative disorder consisting of parkinsonism, mild dementia, supranuclear gaze palsy, and postural instability [57]. Prevalence estimates range from 1.39/100,000 to 6.5/100,000 [58–60], and incidence is estimated to be 5.3 new cases per 100,000 person-years in people 50 to 99 years of age [61]. Estimates of VH prevalence in PSP range from 9.1% to 13.4% [62, 63]. Several studies report phenomenological characteristics of VH in PSP [62, 64–66]. VH are frequently whole people, animals, or fragmented faces. They are familiar sights and occur during twilight or nighttime more often than not. VH can present with an auditory component and may become frightening as complexity increases and disease progresses. The relationship between VH in PSP and antiparkinsonian treatment appears to be equivocal. Nonpharmacological interventions are the first-line treatment, and pharmacotherapy may be useful if the VH become threatening and severely impair quality of life. Antipsychotics show limited utility in treating VH in PSP. However, before implementation, the risk of severe adverse events must be strongly considered [62].

Frontotemporal Dementia

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a term used to define a grouping of pathologically and clinically heterogeneous disorders that demonstrate degeneration of the frontal and temporal lobes. Prevalence estimates range from 4/100,000 to 15/100,000 for those aged 45 to 64 years [67, 68]. Incidence for the same age range is estimated to be 3.5 cases per 100,000 person-years [69]. Studies published after the initial frontotemporal lobar degeneration consensus diagnostic criteria [70] have examined hallucinations, without differentiating sensory types, and report prevalence of hallucinations ranging from 2% to 13% [71–73]. However, per recent review by the Committee on Research of the American Neuropsychiatric Association, there are several reports of psychotic symptoms in FTD with only one case [74] truly showing an association between possible FTD and bizarre VH [75]. Nonpharmacological interventions are the first-line treatment for hallucinations that may arise in people living with FTD. Pharmaceutical management decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis with particular caution given to potential neuroleptic hypersensitivity [76] and other adverse events.

VH in Heredodegenerative and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a progressive, heredodegenerative disorder that presents with neuropsychiatric, cognitive, and motor symptoms. Prevalence of psychosis in HD ranges from 3% to 11% [77], with approximately 2% presenting with hallucinations [78]. Studies of hallucinations in HD often group hallucinations with delusions and examine them collectively rather than individually. Psychiatric symptoms that occur in people living with HD are not related to cognitive or motor presentation [78, 79]. However, they may be related to mood disorders. Once mood disorders, intoxication, and delirium are taken into consideration, antipsychotics may be useful. Assuming neuroleptics are not needed for the control of involuntary movements, newer agents such as risperidone, olanzepine, or quetiapine may be best as these have less chance of extrapyramidal side effects [80]. Systematic review deems risperidone “possibly useful” for the treatment of psychosis in HD [81].

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD), although quite rare, is the most common prion disease affecting humans. Several forms of the disease are currently recognized, including sporadic, familial, iatrogenic, and variant. Rapidly progressive dementia and myoclonus are the cardinal features of sporadic CJD (sCJD). One study describing VH in CJD reports patients hallucinate birds, people, and other visual phenomena [82]. Cases of sCJD are frequently referred to as the Heidenhain variant if visual disturbances, including VH, occur within the first week after onset [83]. VH are present in approximately 13% of Heidenhain variant cases and 2.3% of all sCJD cases [83]. However, other studies show hallucinations of unspecified modality occur in nearly 25% of cases [84].

Although VH occur in other neurodegenerative disorders, this review is unable to address them all. As the neuropsychiatric features of neurodegenerative disorders receive more attention in the literature, a more developed understanding of symptom presentation and treatment options will likely ensue.

Conclusions

Visual hallucinations (VH) are a common feature of neurodegenerative disease. Alpha-synuclein pathology may predispose individuals to develop VH. In PD, VH are frequently treatment related, and may lead to nursing home placement and increased mortality. In DLB, VH are very common, primary, and one of the core diagnostic features. Clinical treatment of VH in neurodegenerative disorders is complex. Neuroleptics should be considered with caution, particularly in disorders with dopamine deficit.

References

Zaccai J, McCracken C, Brayne C (2005) A systematic review of prevalence and incidence studies of dementia with Lewy bodies. Age Ageing 34(6):561–566

McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J et al (2005) Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 65(12):1863–1872

Ballard C, Holmes C, McKeith I et al (1999) Psychiatric morbidity in dementia with Lewy bodies: a prospective clinical and neuropathological comparative study with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 156(7):1039–1045

Aarsland D, Ballard C, Larsen JP et al (2001) A comparative study of psychiatric symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 16(5):528–536

Harding AJ, Broe GA, Halliday GM (2002) Visual hallucinations in Lewy body disease relate to Lewy bodies in the temporal lobe. Brain 125(Pt 2):391–403

Tsuang D, Larson EB, Bolen E et al (2009) Visual hallucinations in dementia: a prospective community-based study with autopsy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 17(4):317–323

Perneczky R, Drzezga A, Boecker H et al (2008) Cerebral metabolic dysfunction in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies and visual hallucinations. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 25(6):531–538

McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K et al (1996) Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology 47(5):1113–1124

Mori E, Shimomura T, Fujimori M et al (2000) Visuoperceptual impairment in dementia with Lewy bodies. Arch Neurol 57(4):489–493

Mosimann UP, Mather G, Wesnes KA et al (2004) Visual perception in Parkinson disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 63(11):2091–2096

Mosimann UP, Rowan EN, Partington CE et al (2006) Characteristics of visual hallucinations in Parkinson disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 14(2):153–160

Ballard CG, O’Brien JT, Swann AG et al (2001) The natural history of psychosis and depression in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease: persistence and new cases over 1 year of follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry 62(1):46–49

McKeith I, Mintzer J, Aarsland D et al (2004) Dementia with Lewy bodies. Lancet Neurol 3(1):19–28

Perry EK, McKeith I, Thompson P et al (1991) Topography, extent, and clinical relevance of neurochemical deficits in dementia of Lewy body type, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 640:197–202

Pakrasi S, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, McKeith IG et al (2003) Clinical predictors of response to Acetyl Cholinesterase Inhibitors: experience from routine clinical use in Newcastle. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 18(10):879–886

Samuel W, Caligiuri M, Galasko D et al (2000) Better cognitive and psychopathologic response to donepezil in patients prospectively diagnosed as dementia with Lewy bodies: a preliminary study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 15(9):794–802

Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P (2005) Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA 294(15):1934–1943

Zhang ZX, Roman GC (1993) Worldwide occurrence of Parkinson’s disease: an updated review. Neuroepidemiology 12(4):195–208

Dorsey ER, Constantinescu R, Thompson JP et al (2007) Projected number of people with Parkinson disease in the most populous nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology 68(5):384–386

Schrag A (2007) Epidemiology of movement disorders. In: Jankovic J, Tolosa E (eds) Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Papapetropoulos S, Mash DC (2005) Psychotic symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. From description to etiology. J Neurol 252(7):753–764

Diederich NJ, Fenelon G, Stebbins G et al (2009) Hallucinations in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol 5(6):331–342

Lewy F (1923) Die Lehre vom Tonus und der Bewegung. Springer, Berlin

Schwab RS, Fabing HD, Prichard JS (1951) Psychiatric symptoms and syndromes in Parkinson’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 107(12):901–907

Papapetropoulos S, Argyriou AA, Ellul J (2005) Factors associated with drug-induced visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 252(10):1223–1228

Tolosa E, Katzenschlager R (2007) Pharmacological management of Parkinson’s disease. In: Jankovic J, Tolosa E (eds) Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Papapetropoulos S, Gonzalez J, Lieberman A et al (2005) Dementia in Parkinson’s disease: a post-mortem study in a population of brain donors. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 20(5):418–422

Fenelon G, Mahieux F, Huon R et al (2000) Hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease: prevalence, phenomenology and risk factors. Brain 123(Pt 4):733–745

Ramirez-Ruiz B, Junque C, Marti MJ et al (2007) Cognitive changes in Parkinson’s disease patients with visual hallucinations. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 23(5):281–288

Santangelo G, Trojano L, Vitale C et al (2007) A neuropsychological longitudinal study in Parkinson’s patients with and without hallucinations. Mov Disord 22(16):2418–2425

Haeske-Dewick HC (1995) Hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease: characteristics and associated clinical features. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 10(6):487–495

Barnes J, David AS (2001) Visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease: a review and phenomenological survey. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 70(6):727–733

Wolters EC (2001) Intrinsic and extrinsic psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 248(suppl 3):III22–III27

Baker MG (1999) Depression, psychosis and dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 52(7 suppl 3):S1

Goetz CG, Fan W, Leurgans S et al (2006) The malignant course of “benign hallucinations” in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 63(5):713–716

Goetz CG, Stebbins GT (1993) Risk factors for nursing home placement in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 43(11):2227–2229

Sinforiani E, Pacchetti C, Zangaglia R et al (2008) REM behavior disorder, hallucinations and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: a two-year follow up. Mov Disord 23(10):1441–1445

Diederich NJ, Pieri V, Goetz CG (2003) Coping strategies for visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 18(7):831–832

Goetz CG, Fan W, Leurgans S (2008) Antipsychotic medication treatment for mild hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease: positive impact on long-term worsening. Mov Disord 23(11):1541–1545

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2009) Deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm053171.htm. Accessed 15 Aug 2009

Knol W, van Marum RJ, Jansen PA et al (2008) Antipsychotic drug use and risk of pneumonia in elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc 56(4):661–666

Miyasaki JM, Shannon K, Voon V et al (2006) Practice parameter: evaluation and treatment of depression, psychosis, and dementia in Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 66(7):996–1002

Abbas A, Roth BL (2008) Pimavanserin tartrate: a 5-HT2A inverse agonist with potential for treating various neuropsychiatric disorders. Expert Opin Pharmacother 9(18):3251–3259

Kurita A, Ochiai Y, Kono Y et al (2003) The beneficial effect of donepezil on visual hallucinations in three patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 16(3):184–188

Burn D, Emre M, McKeith I et al (2006) Effects of rivastigmine in patients with and without visual hallucinations in dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 21(11):1899–1907

Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA et al (2008) Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology 71(9):670–676

Wenning GK, Colosimo C, Geser F et al (2004) Multiple system atrophy. Lancet Neurol 3(2):93–103

Papapetropoulos S, Tuchman A, Laufer D et al (2007) Hallucinations in multiple system atrophy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 13(3):193–194

Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL et al (2003) Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol 60(8):1119–1122

Lobo A, Launer LJ, Fratiglioni L et al (2000) Prevalence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. Neurology 54(11 Suppl 5):S4–S9

Ropacki SA, Jeste DV (2005) Epidemiology of and risk factors for psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a review of 55 studies published from 1990 to 2003. Am J Psychiatry 162(11):2022–2030

Lin SH, Yu CY, Pai MC (2006) The occipital white matter lesions in Alzheimer’s disease patients with visual hallucinations. Clin Imaging 30(6):388–393

Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Kamenetsky JM et al (2005) Hallucinations and mortality in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 13(11):984–990

Bassiony MM, Lyketsos CG (2003) Delusions and hallucinations in Alzheimer’s disease: review of the brain decade. Psychosomatics 44(5):388–401

Scarmeas N, Brandt J, Albert M et al (2005) Delusions and hallucinations are associated with worse outcome in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 62(10):1601–1608

Ballard C, Waite J (2006) The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD003476

Williams DR, Lees AJ (2009) Progressive supranuclear palsy: clinicopathological concepts and diagnostic challenges. Lancet Neurol 8(3):270–279

Golbe LI, Davis PH, Schoenberg BS et al (1988) Prevalence and natural history of progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology 38(7):1031–1034

Schrag A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Quinn NP (1999) Prevalence of progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 354(9192):1771–1775

Nath U, Ben-Shlomo Y, Thomson RG et al (2001) The prevalence of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome) in the UK. Brain 124(Pt 7):1438–1449

Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK et al (1997) Incidence of progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976 to 1990. Neurology 49(5):1284–1288

Papapetropoulos S, Mash DC (2005) Visual hallucinations in progressive supranuclear palsy. Eur Neurol 54(4):217–219

Williams DR, Warren JD, Lees AJ (2008) Using the presence of visual hallucinations to differentiate Parkinson’s disease from atypical parkinsonism. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79(6):652–655

Compta Y, Marti MJ, Rey MJ et al (2009) Parkinsonism, dysautonomia, REM behaviour disorder and visual hallucinations mimicking synucleinopathy in a patient with progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80(5):578–579

Cooper AD, Josephs KA (2009) Photophobia, visual hallucinations, and REM sleep behavior disorder in progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration: a prospective study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 15(1):59–61

Diederich NJ, Leurgans S, Fan W et al (2008) Visual hallucinations and symptoms of REM sleep behavior disorder in Parkinsonian tauopathies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 23(6):598–603

Rosso SM, Donker Kaat L, Baks T et al (2003) Frontotemporal dementia in The Netherlands: patient characteristics and prevalence estimates from a population-based study. Brain 126(Pt 9):2016–2022

Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K et al (2002) The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 58(11):1615–1621

Mercy L, Hodges JR, Dawson K et al (2008) Incidence of early-onset dementias in Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom. Neurology 71(19):1496–1499

Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L et al (1998) Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 51(6):1546–1554

Le Ber I, Guedj E, Gabelle A et al (2006) Demographic, neurological and behavioural characteristics and brain perfusion SPECT in frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 129(Pt 11):3051–3065

Mourik JC, Rosso SM, Niermeijer MF et al (2004) Frontotemporal dementia: behavioral symptoms and caregiver distress. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 18(3–4):299–306

Liu W, Miller BL, Kramer JH et al (2004) Behavioral disorders in the frontal and temporal variants of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 62(5):742–748

Reischle E, Sturm K, Schuierer G et al (2003) A case of schizophreniform disorder in frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Psychiatr Prax 30(suppl 2):S78–S82

Mendez MF, Lauterbach EC, Sampson SM et al (2008) An evidence-based review of the psychopathology of frontotemporal dementia: a report of the ANPA Committee on Research. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 20(2):130–149

Mendez MF, Lipton A (2001) Emergent neuroleptic hypersensitivity as a herald of presenile dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 13(3):347–356

van Duijn E, Kingma EM, van der Mast RC (2007) Psychopathology in verified Huntington’s disease gene carriers. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 19(4):441–448

Paulsen JS, Ready RE, Hamilton JM et al (2001) Neuropsychiatric aspects of Huntington’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 71(3):310–314

Zappacosta B, Monza D, Meoni C et al (1996) Psychiatric symptoms do not correlate with cognitive decline, motor symptoms, or CAG repeat length in Huntington’s disease. Arch Neurol 53(6):493–497

Rosenblatt A, Ranen N, Nance M, et al (1999) A physician’s guide to the management of Huntington’s disease. http://www.hdsa.org/images/content/1/1/11289.pdf. Accessed 1 Sept 2009

Bonelli RM, Wenning GK (2006) Pharmacological management of Huntington’s disease: an evidence-based review. Curr Pharm Des 12(21):2701–2720

Proulx AA, Strong MJ, Nicolle DA (2008) Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease presenting with visual manifestations. Can J Ophthalmol 43(5):591–595

Appleby BS, Appleby KK, Crain BJ et al (2009) Characteristics of established and proposed sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease variants. Arch Neurol 66(2):208–215

Lundberg PO (1998) Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in Sweden. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 65(6):836–841

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2010 Springer

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Papapetropoulos, S., Scanlon, B.K. (2010). Visual Hallucinations in Neurodegenerative Disorders. In: Miyoshi, K., Morimura, Y., Maeda, K. (eds) Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Springer, Tokyo. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-53871-4_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-53871-4_4

Publisher Name: Springer, Tokyo

Print ISBN: 978-4-431-53870-7

Online ISBN: 978-4-431-53871-4

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)