Abstract

In any medical treatment modality, outcome assessment is a major step. For root canal treatment, this primarily means looking at clinical symptoms and assessing radiographs. Moreover, retention is also an important outcome parameter and in this regard questions remain in regard to the association of endodontically treated teeth and overall health of the patient. Therefore, this chapter is dedicated to outcome assessments and decision-making for endodontically treated teeth.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Dental pulp diseases

- periapical diseases

- pulp capping

- pulpotomy

- pulpectomy

- root canal therapy

- root canal treatment

- endodontic retreatment

- apical surgery

- endodontic surgery

Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment. Methods of Diagnosis and Treatment in Endodontics—A Systematic Review. 2010: Report nr 203;1–491. http://www.sbu.se

This comprehensive summary evaluated methods used by dentists to diagnose, prevent and treat inflammation and infection of the dental pulp. Root canal therapy (endodontics) is conducted to ensure healthy conditions in and around teeth, which have been damaged by caries, external trauma or other causes. Despite the overall high standard of dental health in Sweden, root fillings are still common and are expensive items of treatment for both the individual and the society.

8.1 Introduction

Pathosis of endodontic origin develops as a response to microbiological challenges and is mainly a sequel to dental caries. Trauma may be a frequent reason for endodontic treatment in incisors and premolars. But since this book is about molar endodontics, particular aspects on trauma will not be covered in this chapter. In many situations, both pulpitis and apical periodontitis evolve despite the lack of any clinical symptoms and are detected during routine dental visits. However, root canal treatment is mainly initiated because of pain from affected teeth. When people become sick and are suggested a treatment, they have many questions about how their illness and the treatment will affect them. This also holds true for diseases emanating from the dental pulp and periradicular tissues. Some frequently asked questions are likely to be as follows:

-

What will happen to my tooth and my body if pulpitis or apical periodontitis is left untreated?

-

What different treatment options do I have if I decide to keep my tooth?

-

After treatment, will my symptoms disappear?

-

How do disease and treatment affect my risk of losing the tooth?

-

Will treatment cure pulpitis or apical periodontitis?

-

Is there a risk of persistence or relapse of disease?

-

What are my options, if persistence or relapse does occur?

-

Would it be a better idea to take the tooth out?

-

If so, can it be replaced?

8.2 Prognosis

8.2.1 The Scientific Basis for Statements Concerning Prognosis

Prognosis is a prediction of the future course of disease following its onset with or without treatment. Studies on prognosis tackle the clinical questions noted above. A group of patients with a condition such as pulpitis or that have a particular treatment in common, such as root canal treatment, is identified and followed forward in time. Clinical outcomes are measured. Often, conditions that are associated with a given outcome of the disease, that is, prognostic factors, are sought. This is a difficult but indispensable task and may be affected by biases that have to be controlled in these studies. The objective is to predict the future of individual patients and their affected teeth as closely as possible. The intention in the clinical setting is to avoid stating needlessly vague prognoses and answer with confidence when it is deceptive. Therefore, relevant studies aiming to answer the clinical questions must be scrutinized for quality.

The examination comprises evaluation of relevance with regard to subject matter and methodological qualities – study design, internal validity (reasonable protection from systematic errors), statistical power, and generalizability.

Experimental studies in laboratory animals and in vitro studies are generally considered to give only uncertain and preliminary answers to clinical questions. In order to give trustworthy answers to specific clinical questions, only randomized controlled studies, controlled clinical studies, and prospective cohort studies are considered to give the basis for scientific evidence on clinical questions.

8.2.2 Statements About Prognosis in Endodontics

Unfortunately, in recent years, several careful analyses of the scientific basis for the methods that we apply in endodontics have demonstrated extensive shortcomings [1–15]. The situation is worrying for diagnostic and treatment procedures as well as for evaluation of the results of our methods.

It is generally acknowledged by the profession, their patients, and society that practitioners have gathered lengthy clinical experience and that results from in vitro, animal, and clinical studies provide a basis for understanding how the pulp and the periapical tissues respond to therapeutic interventions.

Certainly, many clinical investigations have confirmed that an inflamed pulp may be successfully treated with a conservative procedure, that is, one that is retaining the vital pulp. Yet, to date, there is no analysis available on which clinical conditions define cases that are likely to respond well, and which treatment measures will render teeth functional and asymptomatic.

Many follow-up studies have also demonstrated that teeth with necrotic and infected pulps can be treated endodontically to achieve a healthy outcome that can last many years. This bulk of knowledge has repeatedly been presented in scientific journal reviews and textbooks of endodontics. There are, however, few clinical studies of high scientific quality. Consequently, there is a lack of scientific evidence to show which treatment protocols are the most effective and result in root-filled teeth with minimal risk of recurrent symptoms, periapical inflammation, or loss of the tooth.

Randomized, controlled, and blinded trials are the standard of excellence for comparison of treatment effects and are useful to observe a given treatment method or procedure when all other variables are maintained. At the same time, it is important to bear in mind that there are important parameters, which can influence treatment results, but which cannot be easily controlled in clinical studies. Results of clinical studies must be judged in relation to two broad questions:

-

Can the diagnostic method or treatment work under ideal circumstances?

-

Does it work in ordinary settings?

The label’s efficacy and effectiveness have been applied to these concepts. To a certain degree, this may be a question of the clinician’s experience, ability, attention to detail, meticulousness, and skill. It is seldom possible to assess to what extent such factors influence the results of treatment studies or clinical evaluations. It is however reasonable to assume that in a discipline such as endodontics, these factors are most important because of the technically complicated nature of many endodontic procedures. In particular, in molar endodontics, the diagnosis and treatment are often complex, and the influence on the results of the operator cannot be overvalued. So far, most clinical studies in endodontics have been conducted in academic or specialist settings (efficacy) where devices that substantially facilitate the technical procedures and affect treatment outcomes are widely spread. For the future, it is important that clinical research in endodontics is also conducted in general practice settings, where the majority of endodontic procedures are performed (effectiveness). In this chapter, we try to give an overview of the prognosis for endodontic treatments based on the current and best available evidence and clinical experience, as it has been presented in textbooks, at conferences, and other professional venues. Furthermore, we point out some of the obvious knowledge gaps and controversies in the science of clinical endodontics.

8.3 Natural History of Disease

The prognosis of a disease without interference is termed the natural history of disease. A great many teeth with pulpitis and apical periodontitis, even in countries with well-developed dental care, often do not come under dental treatment. They remain unrecognized, because they are asymptomatic or are considered among the ordinary discomforts of daily living. Or, the patient may be suffering both pain and other symptoms for a prolonged period of time, but because of economic limitations has not been able to seek dental care.

Numerous teeth with only small caries lesions in the dentin, sometimes even when lesions are confined to the enamel only, develop inflammatory changes in the pulp.

As long as the caries is still in the periphery, the pulp is regularly able to endure the challenge caused by bacteria in the dentine. The quicker the progression and the deeper the lesion gets, the more severe the inflammatory response in the pulp. When the caries lesion continues to progress, pulp vitality is jeopardized. Once the bacterial front extends into reparative dentin or the pulp tissue proper, it may finally reach a point of no return. Pulp necrosis will sooner or later follow. It is known that the disease can be severe without causing patients symptoms, even if the pulpitis eventually leads to pulp necrosis. Also, dental procedures and different forms of accidental trauma may cause injury, leading to pulp necrosis. In molars with two or more roots, it is a common feature that in one root total pulp necrosis has already occurred, while in another root, the pulp is still vital but severely inflamed.

Collapse of the dental pulp by any cause results in loss of the defense mechanisms that can counteract microorganisms in the oral cavity from entering into the root canal system. In cases of direct exposure such as caries or fracture, microorganisms rapidly invade the available pulpal space. In apparently intact teeth, microorganisms will ultimately find ways to access the root canal through fractures, cracks, or from accessory lateral and furcal canals in teeth with periodontal breakdown. In restored teeth, the pathway may be via dentinal tubules under restorations with marginal gaps. The invasion of microorganisms is a prerequisite for the development of apical periodontitis.

As the microbiota of the mouth invades the necrotic pulpal tissue, an inflammatory reaction, that is, apical periodontitis, will develop outside the root canal system adjacent to the foramina. One of the main features of apical periodontitis is the appearance of an osteolytic area due to the increased activity of osteoclasts. In early stages, the loss of mineral is not enough to be detected in traditional intraoral radiographs. However, eventually, a visible periapical radiolucency will develop. Inflammatory periapical lesions associated with an infected necrosis of the root canal system may prevail without clinical or subjective signs (pain, tenderness, sinus tracts, or swelling). However, symptomatic apical periodontitis may develop spontaneously. Severe pain might develop with or without soft-tissue swelling. Spread of an infection may occasionally lead to life-threatening conditions. Abscesses can spread to the sublingual space and lead to elevation of the tongue followed by occlusion of the airways or toward the eye and ophthalmic vein, which in turn is in contact with the brain through the cavernous sinus.

The natural history of teeth with a necrotic pulp and apical periodontitis on a population basis are to a great extent unknown. Some sparse information may be extradited from the few longitudinal observational studies on teeth and endodontic status. For example, Kirkevang et al. 2012 [16] presented data from a Danish cohort of 327 individuals who participated in three consecutive full-mouth radiographic examinations with 5-year intervals. It was possible to follow-up 33 teeth with apical periodontitis over a period of 10 years. At the last follow-up examination, five untreated teeth were diagnosed without signs of apical periodontitis (15 %) and five untreated teeth remained with signs of apical periodontitis (15 %). Nine teeth had root fillings (27 %) and fourteen teeth were lost (42 %). As a contrast, only 98 of 8225 teeth (1 %) without apical periodontitis at baseline were lost during the same period. Ideally, prospective longitudinal studies on natural history of necrotic teeth should include both clinical and radiographic observations. However, there are ethical and practical considerations making such studies, if not impossible, at least very difficult to implement.

8.4 Clinical Course

The term clinical course has been used to describe the evolution (prognosis) of disease that has come under medical or dental care and treated in a variety of ways that might affect the subsequent course of events. Treatment of pulpal and periradicular pathology is inserted at different stages of disease development. As long as the pulp remains vital, there is a possibility of reversing the progression of disease and preserve the pulp. The advantage of preserving the pulp tissue is most obvious in the case of a young permanent tooth with a large pulp chamber and undeveloped root, because removing the pulp arrests root development. The dentinal walls in the root will then be thin, increasing the risk of root fracture. A root-filled tooth in an adult also carries with it the risk for fracture. The prognosis in terms of the survival rate of root-filled teeth is not as good as vital teeth, especially in molars. Possible reasons include the loss of proprioceptive function, damping property, and tooth sensitivity, once a vital pulp succumbs to necrosis or is removed by pulpectomy. From a cost aspect as well, the alternative of retaining all or some of the pulp is preferable. The clinicians’ challenge is to distinguish conditions where pulp can be preserved and cured (reversible pulpitis) from those in which the pulp is so extensively damaged that the road to complete necrosis is inevitable (irreversible pulpitis). Unfortunately, there is no scientific basis on which to assess the value of pain or other markers of inflammation intended to differentiate between reversible and irreversible pulpitis [13].

8.5 Vital Pulp Therapies

8.5.1 Caries in Primary Dentin

The most basic and simple treatment of reversible pulpitis consists of stopping the progression of caries. Beyond a certain point, excavation of a caries lesion is considered necessary, and a filling is placed to restore the dentin. The prognosis of the pulp after caries removal and placement of a filling is probably very good. However, large cohort studies focusing on pulpal pathology after restorative procedures are surprisingly rare. In a randomized trial investigating the dentine and pulp protection by conditioning-and-sealing versus a conventional calcium hydroxide lining, Whitworth et al. 2005 [17] studied a cohort of 602 teeth, which were restored with composite fillings. Over a period of 3 years, 16 teeth (2,6 %) developed clinical signs of pulpal breakdown. The residual dentine thickness is generally believed to be a key prognostic factor in these situations. Deep lesions are considered being more at risk for pulpal collapse than shallow ones.

8.5.2 Deep Caries

If the carious lesion with its bacterial front enters the primary dentin and progresses into the reparative dentin zone or even into the pulp tissue proper, the inflammatory response in the pulp becomes massive. In the above-mentioned study by Whitworth et al. [17], pulp exposures appeared strongly associated with an unfavorable pulp outcome. These observations have led authors to propose that treatment methods where pulp exposure is avoided should be preferred over those in which the pulp is at risk of being exposed [14].

There are basically two methods available to avoid exposure of the pulp: Indirect pulp capping and stepwise excavation. With both methods, a layer of carious dentine is left undisturbed. The difference between the two methods is that in the former the tooth is left without further intervention, whereas the latter includes a re-entry for checkup and possible further excavation at a later (3–6 months) session. In a review published in 2013, eight clinical trials with 934 participants and 1372 teeth were scrutinized [14]. Four studies investigated only primary teeth, three permanent teeth, and one included both. Both stepwise and partial excavation without re-entry reduced the incidence of pulp exposure in symptomless, vital, and carious primary as well as permanent teeth. Therefore, these techniques seem to have clinical advantage over complete caries removal in the treatment of deep dentinal caries. Unfortunately, these studies have debilitating characteristics and do not provide the scientific basis to evaluate differences in pulpal survival rates following immediate complete caries excavation or stepwise excavation in the long term.

8.5.3 Pulp Exposure

If the pulp is exposed, four more or less different treatment options are available.

The pulpal wound can be covered with a dressing (direct pulp capping). Another approach is to remove the outermost layer of pulpal tissue and apply a dressing to the wound (partial pulpotomy). Yet another option is to remove the contents of the pulp chamber and locate the surface of the wound at the opening of the root canal (pulpotomy). The most radical method is to remove all of the pulp tissue from the pulp chamber and the root canals (pulpectomy) and replace it with a root filling.

Caries is the most common cause of pulp exposure. The outcome of the three above-mentioned treatment options available in order to retain the vitality of all or part of the pulp (direct pulp capping, partial pulpotomy, and full pulpotomy) in permanent teeth with cariously exposed pulps has been reviewed by Aguilar and Linsuwanont [10]. Over a period of 3 years, a clinically favorable outcome (tooth in an asymptomatic state without signs of pulpal necrosis and subsequent infection) was in the range of 73–99 % with no conclusive advantage neither for any of the three types of treatment, nor for clear answers as to what factors might influence treatment outcome. It is a common opinion among clinicians that various symptoms and clinical findings may indicate that the pulp is irreversibly inflamed. The significance of persistent toothache, radiographic changes in the periapical region, abnormal pain reactions to thermal stimuli, and/or abnormal bleeding from an exposed pulp as signs for the prognosis of a treatment aimed to preserve the pulp has not been studied sufficiently well. In another review of the matter, it was concluded that there is limited scientific support that preoperative toothache increases the risk of failure of direct pulp capping [9]. This Swedish comprehensive review applied stricter inclusion criteria for studies. Their main conclusion on the topic was also that there is no scientific basis for assessment of which method, direct pulp capping, partial pulpotomy, or pulpotomy gives the most favorable conditions for maintaining the pulp in a vital and asymptomatic condition (Box 8.1).

Box 8.1. Follow-Up After Treatments Aiming at Preserving a Molar’s Pulp Vitality

Evaluation | Signs of favorable outcome | Checklist |

|---|---|---|

Subjective symptoms | Asymptomatic, comfortable, and functional | √ |

Restoration | Good-quality restoration with no signs of caries | √ |

Pulp sensitivity | Normal positive response to thermal or electric pulp testing | √ |

Periradicular tissues Clinical | No signs of swelling, redness, or sinus tract | √ |

Periradicular tissues Radiographic | No signs of periradicular bone destruction | √ |

8.5.3.1 Pulpectomy

Complete removal of the pulp and placement of a root filling is the most extreme treatment approach when a pulp has been exposed. The scientific literature on pulpectomy is limited, and in particular there are no studies of direct comparison between the results of pulp preservation therapies with pulpectomies. Furthermore, many follow-up studies have not been able to make a clear distinction between teeth with vital but inflamed pulps and necrotic ones. In a randomized controlled study [18], the outcome of pulpectomy in one or two treatment sessions was assessed by a single dentist specialized in endodontics who carried out the treatments. A majority of the teeth in the study were affected by caries and had symptoms because of pulpitis. In both treatment groups, teeth were asymptomatic and without clinical and radiological signs of periapical infection or inflammation in 93 % of the cases, with a follow-up time up to 3 years.

In another clinical study [19], where supervised dental students carried out the pulpectomies and root fillings, it was found that after an observation period of 3.5–4 years, teeth with positive bacterial samples at the time of root filling had a poorer outcome than that of teeth with negative samples. Also, significantly more unfavorable outcomes were noted after 3.5–4 years than after 1 year of observation. The findings are in concordance with the results of a review on the outcome of primary root canal treatments (including pulpectomies) in which four conditions were found to improve the outcome of primary root canal treatment significantly [4]. One of these factors, the absence of periapical radiolucency, indicates that a noninfected root canal is a prognostic factor favoring an outcome where no signs of apical periodontitis will develop. Consequently, holding on to a strict protocol for asepsis seems to be of importance when carrying out a pulpectomy.

8.5.4 Symptomatic Pulpitis

Many endodontic procedures begin in an emergency situation. Symptoms from an inflamed dental pulp vary from only enhanced sensitivity to thermal, osmotic, and tactile stimuli to conditions of severe lingering and tearing pain. Patients with pain may require pulpectomy in the long term, but in an emergency situation pulpotomy has a good effect. If pulpotomy can be applied with good results on longer term is not well known [13]. A recent published study seems to indicate that pulpotomy in molars performed with biocompatible materials may be as successful as pulpectomy in achieving favorable clinical results when performed by general dental practitioners [20].

8.6 Treatment of Pulp Necrosis and Apical Periodontitis

8.6.1 Pulp Necrosis and Asymptomatic Apical Periodontitis

Injury to the pulp may eventually lead to a complete breakdown of the tissue. The nonvital or necrotic pulp is defenseless against microbial invasion and will sooner or later be infected by indigenous microorganisms. No established methods exist to allow for debridement and antimicrobial combat and a subsequent reestablishment of a vital adult pulp. However, ongoing research within this area may change the treatment options in the future [21]. For the time being, the only established treatment modality in teeth with completed root formation is root canal treatment. The root canal is cleaned in order to remove microbes and their substrates. In addition to irrigants, antimicrobial substances are used as dressings to enhance the antibacterial effect. A root canal treatment is finished as the tooth receives a permanent root filling. Postoperative discomfort sometimes follows, but after a short period most teeth become asymptomatic. Normally, the tooth is restored with a filling or crown immediately or a short while after completion.

8.6.2 Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis

Most teeth with pulp necrosis and apical periodontitis prevail without acute signs of inflammation. Nevertheless, symptoms may develop spontaneously or be initiated in conjunction with root canal treatment. The symptoms may vary from relatively mild pain to life-threatening situations with abscesses or cellulites. In an acute situation, the clinician needs to deliberate on the seriousness and deploy adequate measures. These can range from simple root canal instrumentation to incision of an abscess with or without prescription of analgesics and antibiotics. The appropriateness of different measures depends on the risk of the spread of infection and the patient’s general health. When the acute phase has subsided, the affected tooth needs root canal treatment, which is performed in the same manner as for asymptomatic cases. There is no evidence that shows that teeth that have gone through a phase of symptomatic apical periodontitis have a worse prognosis than those that have not.

8.6.3 Successful Outcome of Root Canal Treatment

The desirable and best possible long-term outcome of root canal treatment is a retained and functional asymptomatic tooth with no clinical or radiographic signs of apical periodontitis. Ng et al. [4] identified 63 studies published from 1922 to 2002, which fulfilled their inclusion criteria for a review. The reported mean rates of a “successful” outcome ranged from 31 to 100 %. This large variation could partly be the result of different radiographic criteria when evaluating the periradicular tissues on radiographs.

Despite the lack of high-quality scientific evidence, a meticulous analysis of the literature pointed out four circumstances that improve the possibility to maintain or reestablish healthy periradicular tissues in root-filled teeth: (i) preoperative absence of periapical radiolucency, (ii) root filling with no voids, (iii) root filling extending to 2 mm within the radiographic apex, and (iv) satisfactory coronal restoration [4], (Box 8.2). If these conditions are attainable, root canal therapy has been reported to be able to fulfill the requirements of “complete success” in 85–95 % of cases. Clinical experience and data from studies [4, 16, 18, 22, 23] have shown that root-filled teeth can be retained and stay healthy for many years.

Box 8.2. Prognostic Factors for Pulpectomy and Root Canal Treatment

Prognostic factors for pulpectomy and root canal treatment | Checklist |

|---|---|

Enough remaining tooth structure for a restoration that can avoid or counteract with adverse masticatory forces | √ |

Aseptic control and disinfection measures applied during treatment | √ |

A root-filling without voids in all main root canals | √ |

A root-filling extending to 2 mm within the radiographic apex | √ |

A good-quality coronal restoration | √ |

8.6.4 Unsuccessful Outcome of Root Canal Treatment

When root-filled teeth cause pain, it is usually a sign of infection. Especially so, if corresponding clinical findings in the form of swelling, tenderness, and fistulas at the same time are present. In situations like these, it is usually frank to diagnose a persistent, recurrent, or arising apical periodontitis. The treatment result is classified as a “failure.” There is an obvious indication for a new treatment intervention, retreatment, or extraction of the tooth (or sometimes only a root).

8.6.5 Asymptomatic and Functional but Persisting Radiological Signs of Apical Periodontitis

Nevertheless, a common situation is that the root-filled tooth is both subjective and clinically asymptomatic but an X-ray reveals that bone destruction has developed, or that the original bone destruction remains. In cases where no bony destruction was present when root canal treatment was completed, and in particular in cases of vital pulp therapy, it can be rationally assumed that microorganisms have entered in the root canal system. For teeth that showed clear bone destruction at the point of treatment, sufficient time must be allowed for healing and bone formation to occur.

8.6.6 Uncertainties in Classifying the Outcome into “Success” and “Failure”

8.6.6.1 The Time Factor

It is difficult to determine the amount of time that may be required for a periapical bone lesion to heal. A majority of root canal treated teeth with initial bone destruction show signs of healing within 1 year [24]. However, in individual cases, the healing process can take a long time [22]. In a study by Molven et al. [23], it was reported that some cases had required more than 25 years to completely heal. The finding that there is no absolute time limit for when healing may eventually be diagnosed can also be deduced from epidemiological studies [16].

8.6.6.2 The Reliability and Validity of Radiographic Evaluation

The diagnosis of periapical tissues based on intraoral radiographs is subject to considerable interobserver and intraobserver variations [12].

There are also uncertainties regarding the validity of the radiographic examination. Only a limited number of studies have compared the histological diagnosis in root-filled teeth to radiographic signs of pathology [12, 25]. In these studies, false-positive findings (i.e., radiographic findings that indicate apical periodontitis while histological examination does not) are rare. The number of false-negative findings (i.e., radiographic evaluation indicates no apical periodontitis while histological examination gives evidence for inflammatory lesions) varies between the studies. However, from experimental studies, it is well known that bone destruction and consequently apical periodontitis may be present without radiographic signs visible in intraoral radiographs.

The advent of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) has attracted much attention in endodontics in recent years [12]. In vitro studies on skeletal material point to that the method has higher sensitivity and specificity than intraoral periapical radiography. The higher sensitivity of CBCT is confirmed in clinical studies. CBCT provides a three-dimensional image of the area of interest, an advantage when assessing the condition of multirooted teeth. As a result, the reliability of results of endodontic treatment in follow-up using conventional intraoral radiographic technique has been questioned [26]. It has been suggested that CBCT should be used in future clinical studies, because conventional radiography systematically underestimates the number of teeth with osteolytic lesions. In this respect, long-term studies are required to investigate if healing of periapical bone destruction may take longer than previously assumed. Also, there is not enough scientific evidence to tell whether lesions on CBCT images provide accurate clues as to the histological diagnosis present. So far, there are also disadvantages of CBCT, such as greater cost and a potentially higher radiation dose. Up to date, there is no evidence that suggests that individuals with subjectively and clinically asymptomatic root canal treated teeth with normal appearance of surrounding bony structures in an intraoral radiographic examination would benefit from further evaluation by a CBCT scan.

8.6.6.3 Controversies of “Success” and “Failures” of Root Canal Treatment

Besides the time aspect of periapical bone lesions, there is also a problem with determination of what should be considered healing sufficient to constitute a “successful” endodontic treatment. As a consequence, the question of what establishes a “failure” and hence an indication for retreatment is far from unmistakable. According to the system launched by Strindberg [22], the only satisfactory post-treatment situation, after a predetermined healing period, combines a symptom-free patient with a normal periradicular situation. Only cases fulfilling these criteria were classified as “success,” and all others as “failures.” In academic environments and in clinical research, this strict criteria set by Strindberg in 1956 [22] has had a strong position.

The periapical index (PAI) scoring system was presented by Ørstavik et al. [27]. The PAI provides an ordinal scale of five scores ranging from “healthy” to “severe periodontitis with exacerbating features” and is based on reference radiographs with verified histological diagnoses originally published by Brynolf [25]. The results from Brynolf’s work indicated that by using radiographs, it was possible to differentiate between normal states and inflammation of varying severity. However, the studies were based on a restricted biopsy material to upper anterior teeth. Among researchers, the PAI is well established, and it has been used in both clinical trials and epidemiological surveys. Researchers often transpose the PAI scoring system to the terms of Strindberg system by dichotomizing scores 1 and 2 to “success” and scores 3, 4, and 5 into “failure.” However, the “cutoff” line is arbitrary.

The Strindberg system, with its originally dichotomizing structure into “success” and “failure” has achieved status as a normative guide to action in clinical contexts. Consequently, when a new or persistent periapical lesion is diagnosed in a root-filled tooth, failure is at hand and retreatment (or extraction) is indicated.

However, as early as 1966, Bender and colleagues [28] suggested that arrested bone destruction in combination with an asymptomatic patient should be a sufficient condition for classifying a root canal treatment as an endodontic success. More recently, Friedman and Mor [29] as well as Wu et al. [30] have suggested similar less strict classifications of the outcome of root canal treatment.

8.6.6.4 Prevalence of “Failures”

The presence of subjective or clinical signs of failed root canal treatment is only occasionally reported in published follow-ups and epidemiological studies. The results are measured thus exclusively through an analysis of X-rays. In epidemiological cross-sectional studies, the frequency of periapical radiolucencies in root-filled teeth varies. In a systematic review of the matter, Pak et al. [31] included 33 studies from around the world with frequencies of failed cases varying from 12 to 72 %. The weighted average of periapical radiolucencies in the 28,881 endodontically treated teeth included was 36 %. The high frequency of root-filled teeth with periapical bone destructions seems to persist regardless of the fact that technical quality has improved over time [31]. Yet, cross-sectional studies cannot distinguish between cases that will finally heal and osteolytic lesions that will persist. On the other hand, longitudinal studies have shown that root-filled teeth without periapical radiolucent areas may develop visible lesions over time [16].

8.6.6.5 Consequences of “Endodontic Failures”

8.6.6.5.1 Persistent Pain

Surprisingly little is known about the frequency of pain from root-filled teeth. From the available data in follow-up studies from universities or specialist clinics, in a systematic review, the frequency of persistent pain >6 months after endodontic procedures was estimated to be 5 % [7].

8.6.6.5.2 Local Spread of Disease

A large majority of root-filled teeth with apical periodontitis remain asymptomatic. It is known that the inflammatory process occasionally turns acute with the development of local abscesses that have the potential for life-threatening spread to other parts of the body. Case reports in the literature describe the occurrence of more or less serious complications in the nearby organs (respiratory tract, brain), due to spread of bacterial infection from the root canals of teeth. However, the incidence and severity of exacerbation of apical periodontitis from root-filled teeth has met only scarce attention from researchers. A low risk of painful exacerbations (1–2 %) was reported from a cohort of 1032 root-filled teeth followed over time by Van Nieuwenhuysen et al. [32]. In a report from a university hospital clinic in Singapore where 127 patients with 185 nonhealed root-filled teeth were recruited [33]. Flare-ups occurred only in 5.8 % over a period of 20 years. Less severe pain was experienced by another 40 % over the same time period. The incidence of discomforting clinical events was significantly associated with female patients, treatments involving a mandibular molar or maxillary premolar, and preoperative pain.

8.6.6.5.3 Systemic Effects

Oral infections have been associated increasingly with severe systemic diseases, such as atherosclerosis, stroke, and even cancer. The potential of an association between chronic marginal periodontitis and cardiovascular disease is recognized in numerous reports. Indeed, the increasing numbers of reports of a relationship between atherosclerotic vascular diseases prompted a systematic review and American Heart Association Scientific Statement that examined possible correlations [34]. However, no clear answers to the questions about the possible causative relationship between atherosclerotic vascular disease and periodontal disease could be established.

Less attention has been given to a corresponding association with disease processes originating in the dental pulp. The scientific basis is insufficient to assess the association between infections of endodontic origin and disease conditions of other organs [9].

8.6.6.6 Disease Concepts

To retreat or not to retreat “an endodontic failure” is the issue. It has been argued that both modern medicine and dentistry face fundamental ethical problems if too rigorous and consistent concepts of disease prevail. The discussion about different concepts of disease goes back to ancient philosophy and has bewildered and occupied philosophers ever since. In this book about molar endodontics, we can only hint at the fundamental issues. For further reading, the interested reader should seek in books on philosophy of medicine [35].

Two fundamentally different concepts of disease can traditionally be recognized.

-

The naturalist theory defines disease in terms of biological processes. Disease is a value-free concept, existing independently of its social and cultural contexts. Disease is discovered, studied, and described by means of science.

-

The normativist theory, on the other hand, declares that there is no value-free concept of disease. Rather than discovered, the concept of disease is invented. It is contextual and given by convention.

These theories address different aspects and pose different challenges to medicine and dentistry as a whole and therefore also to endodontics. But the two predominant concepts have been challenged for several reasons. For example, they neither separately nor together fully acknowledge all important perspectives on human disorders. An alternative approach is to apply the “triad of disease, illness, and sickness” [36] (Box 8.3). Despite criticism, the triad is widely used and discussed. The definition of the triad’s different components is by no way clear-cut. The triad and its implications on dentistry were elaborated by Hofmann and Eriksen [37]. Kvist et al. [38] made cautious and initial attempts to apply the theory to the problem of asymptomatic root-filled teeth with radiographic signs of apical periodontitis.

Box 8.3. An Attempt to Apply the Triad of Disease, Illness, and Sickness to Root-Filled Teeth with Signs of Apical Periodontitis

Disease | Illness | Sickness | |

|---|---|---|---|

Phenomena studied | Pathophysiological, histological, microbiological, and radiographic events | Pain, swelling, or other symptoms presented now or in the future | Criteria for classification and grading of disease |

Validity | Objective | Subjective | Intersubjective |

Purpose from the professions’ point of view | To study the medical facts of apical periodontitis in order to improve knowledge of how to prevent and cure | To identify and describe the incidence, frequency, and intensity for patient-related outcomes (pain, swelling, spread) | To decide upon common criteria for classification, define different severities of disease, and construct decision aids to guide clinical action |

Purpose from patients’ point of view | To get an explanation of the situation | To value and accept or not accept the situation | To understand what is regarded “sick,” respectively “healthy,” and to be helped to make a clinical decision in his or her situation |

-

Disease means the disorder in its physical form, the biological nature, the clinical, and paraclinical findings (histology, microbiology, radiography, etc.).

-

Illness is used to describe a person’s own experience of the disease, how it feels, and what sufferings it gives now or in the future. Illness also includes anxiety and anguish.

-

Sickness is the third label; it tries to capture the social role of a person who has illness or disease (or both) in a particular cultural context. What is eligible for being “sick” can consequently vary over time and between societies.

The three approaches to disease do not replace but complement each other. It is also the case that they are strongly intertwined. However, using the above matrix of “disease,” “illness,” and “sickness” makes it easier to understand the variation in clinical decision-making regarding root-filled teeth with persistent apical lesions, both when it is tested in different setups by researchers as well as in the clinical situation with an individual patient.

8.6.6.7 Patient Values

In front of a situation with a root-filled tooth with persistent apical periodontitis, dentists and their patients choose different clinical management despite identical information. Both doctors’ and patients’ values will influence the decision-making process. The concept of value has many aspects, but it is reasonable to suppose that there is a close connection between an individual’s values and his or her preferences and value judgments. The concept of personal values in clinical decision-making about apical periodontitis has been explored among both dental students and specialists by Kvist and Reit [39]. Substantial interindividual variation was registered in the evaluation of asymptomatic apical periodontitis in root-filled teeth. From a subjective point of view, some patients will benefit much more from endodontic retreatment than others (Box 8.4).

Box 8.4. Checklist for the Outcome of Endodontic Treatment of the Root Canal System

Evaluation | Signs of favorable outcome | Checklist |

|---|---|---|

Subjective symptoms | Asymptomatic, comfortable and functional | √ |

Restoration | Good-quality restoration with no signs of caries | √ |

Periradicular tissues Clinical | No signs of swelling, redness, or fistula No deep probing depths | √ |

Periradicular tissues Radiographic | No, or only small signs of periradicular bone destruction Or, a periradicular bone destruction of decreasing size over time | √ |

Today, patient autonomy is widely regarded as a primary ethical principle, emphasizing the importance of paying attention to the values and preferences of each individual patient.

8.6.6.8 Variation in Clinical Decisions About “Endodontic Failures”

The diagnostic difficulties, timing, the question of what should be regarded as healthy and diseased, patient values, as well as several other factors partly explain the large variation among dentists regarding retreatment decision-making. This situation has been highlighted in numerous publications. The issue was comprehensively reviewed by Kvist [40]. From the many investigations conducted, it stands clear that the mere diagnosis of persisting periapical bone destruction in a root-filled tooth does not consistently result in decisions for retreatment among clinicians. Theoretically, four options are available:

-

1.

To accept the situation and leave it without further follow-ups or treatment

-

2.

To accept the situation for time being and expose the tooth for continued follow-up

-

3.

To extract the tooth (or root)

-

4.

To endodontically retreat the tooth

If retreatment is selected, the decision-maker also has to make a choice between a surgical and nonsurgical approach.

Our discussion will be adequate if it has as much clearness as the subject-matter admits of, for precision is not to be sought for alike in all discussions,…for it is the mark of an educated man to look for precision in each class of things just so far as the nature of the subject admits. Aristotle (350 BC) Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by: W D Ross.

8.6.7 Tooth Retention Over Time

Two longitudinal studies in Scandinavian populations found that 12–13 %, respectively, of the teeth that were root filled at the baseline examination were extracted at follow-up approximately 10 years later [16, 41]. In the Danish population, it was found that teeth with apical periodontitis (nonroot-filled and root-filled) had six times higher risk of being lost than periapically healthy teeth [42]. However, findings suggest that other causes than apical periodontitis such as periodontal disease, caries, or root fracture are frequently present when root-filled teeth are extracted [43, 44].

In a systematic review on tooth survival following nonsurgical root canal treatment, 14 studies published between 1993 and 2007 were included. The authors concluded that the pooled proportion of teeth surviving over 2–10 years ranged between 86 and 93 % [6]. Four prognostic factors were found to significantly improve tooth survival: (i) A crown restoration after completion of root canal treatment, (ii) tooth having both approximal contacts, (iii) tooth not functioning as an abutment in a prosthodontic construction, and (iv) not being a molar tooth. However, the authors pointed to the fact that the results of the review should be interpreted with care because of the methodological limitations of available studies.

For example, it is difficult to tell whether the observed correlations are causative or a consequence of biased selection of cases. It seems likely that dentists and their patients, would be more prone to invest in placing a crown on a tooth with perceived good prognosis rather than on the one with questionable forecast. Consequently, the finding about the positive effect of the crown placement may be a self-fulfilling prophecy. The reason why molars, teeth without approximal contacts and abutments in prosthesis more often have been extracted in a follow-up may be a result of the fact that these teeth are more dispensable and acceptable to extract from a patient’s point of view if any additional signs of disease appears. In the above-mentioned review, the authors concluded that the available data support the common opinion among clinicians that tooth survival is likely to be influenced by the strength and integrity of the remaining tooth tissue and the manner in which forces are distributed within the remaining tooth tissue when in masticatory function.

8.7 Retreatment

8.7.1 Surgical or Nonsurgical Retreatment

Chronic periapical asymptomatic lesions as well as exacerbation or aggravation of persistent apical periodontitis of root-filled teeth may be cured by endodontic nonsurgical or surgical retreatment. There is insufficient scientific support on which to determine whether surgical and nonsurgical retreatments of root-filled teeth give systematically different outcomes, both in the short and long terms, with respect to healing of apical periodontitis or tooth survival [3, 8, 9]. In clinical practice, a number of factors influence the choice of treatment, for example, the size of the bone destruction, the technical quality of previous treatment, accessibility to the root canal, future restorative requirements of the tooth, the cost of treatment, the preferences of the clinician and the patient, medical considerations, the availability of various types of special equipment.

The clinical decisions will have to be made on the basis of unique conditions applying to every case.

8.7.2 The Size of the Bone Destruction

Apical periodontitis may develop into cysts. Periapical cysts are classified as “pocket-cysts” or “true-cysts.” In case of a pocket cyst, the cyst cavity is expected to heal after proper conventional root canal treatment. A true cyst, on the other hand, is supposed not to respond to any intracanal treatment efforts. Thus, it is supposed that true radicular cysts have to be surgically resected in order to heal [45]. Unfortunately, there is no scientific evidence to clinically determine the histological diagnosis of the periapical tissue in general, and in particular, there is no method to distinguish between pocket-cysts and true-cysts other than histology [12]. However, cysts are expected to be more predominant among large bony lesions [46]. Thus, in case of large bone destruction, much speaks for a surgical retreatment.

8.7.3 The Technical Quality of the Previous Treatment

In cases of nonhealed apical periodontitis, the technical quality of the root filling is often poor [31]. In molars, the reason for treatment failure may be associated with untreated canals. In many cases, therefore, a nonsurgical retreatment should be considered. In particular, this is the case when access is not hindered by a crown and post. Since there is convincing findings that the quality of the restoration also plays a significant part for the periapical status in root filled teeth [11] the clinician is recommended to have a critical look at the restoration. If restoration is of poor quality, it may jeopardize the results of an endodontic surgery [15].

The obvious objective for a nonsurgical retreatment is to treat the previously untreated parts of the root canal system and thus improve the quality of root canal filling. With the help of modern endodontic armament, this is often possible to achieve. Studies have shown that nonsurgical retreatment performed by skillful clinicians results in good chances of achieving periapical healing [47, 48].

Several authors have argued that the result of endodontic surgery is dependent on the good quality of the root filling, and consequently argued that any endodontic surgery should be preceded by a nonsurgical retreatment. No clear evidence exists of the benefit of this approach, and it would moreover, if used orderly, lead to the execution of a significant amount of unnecessary surgeries. In many cases, the nonsurgical retreatment per se would be enough to achieve healing of the periapical tissues.

8.7.4 Accessibility to the Root Canal

Root-filled teeth are often restored with posts and crowns, and are frequently used as abutments for bridges and other prosthodontic constructions which have to be removed or passed through for a nonsurgical approach. In cases where the quality of restorations is adequate, a surgical approach is more appealing. Even without hindering restorations, a preoperative analysis of the case may reveal intracanal ledges or fractured instruments that already preoperatively make the accessibility to the site of the residual infection questionable [47].

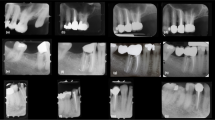

On the other hand, access to the site of infection by endodontic surgery can be judged to imply major difficulties. In particular, surgery involving mandibular molar roots as well as palatal roots of the maxillary molars sometimes offers significant operator challenges. Preoperative CBCT scans help the surgeon to plan the intervention or sometimes to refrain and choose a nonsurgical approach, or even considering extraction and a different treatment plan (Fig. 8.1).

Radiographs showing details for the evaluation and treatment of the left mandibular second molar (tooth 46 FDI or #30 Universal). The patient is female, born 1945. There is pain from lower right jaw region; the tooth in question was root canal-treated 3 years earlier. Both right mandibular molars are tender to percussion, and the second molar is not sensitive to electric and thermal pulp testing. Radiographically, there are radiolucent areas associated with both molars. (a) Preoperative periapical radiograph. (b) Left and right, Root canal treatment of 47 (#31). Note the fill of lateral canal. (c) Left and right, Follow-up after 6 months. Asymptomatic patient. Note that 44 (#28) also has a root filling and a periapical radiolucent area. (d) Left and right, Additional follow-up 1 year later. Note bone fill apically to 47 (#31) and 44 (#28). However, periapical radiolucent area 46 (#30) persists. The tooth is slightly tender to percussion. The decision is made to perform surgical retreatment 46 (#30). (e) Immediate postoperative surgery 46 (#30). (f) Left and right, 1-year follow-up after surgery. Patient asymptomatic. Good healing of periapical lesions 47, 46, 44 (#31, 30, 28)

8.7.5 Future Restorative Requirements of the Tooth

Before considering retreatment of a previously root-filled tooth, there is a need for careful deliberation of the overall treatment plan. In many cases, the issue is rather straightforward. It might concern a single tooth, restored with a post and a crown of fully acceptable quality, but with an ensured diagnosis of persistent apical periodontitis. The objective is to cure the disease and to “save” the tooth and its restoration in the long term. In other situations, when complete mouth restorations are planned to “build something new,” the strategic use of teeth, nonroot filled as well as root filled, and dental implants to minimize the risk of failure of the entire restoration must be the first priority [49].

8.7.6 The Cost of Treatment

Since surgical endodontics does not require the dismantling of functional prosthodontics constructions, it is often a less expensive alternative for the patient. But, the costs of both surgical and nonsurgical treatments, of course, vary both in different countries between operators and between countries with different systems of reimbursement by insurance.

8.7.7 The Preferences of the Clinician and the Patient

Whether a retreatment, nonsurgical or surgical, should be performed is a complex decision, with many factors to be considered. When a diagnosing dentist is asked to suggest a treatment plan with alternatives, both biological considerations and the potential and limitations of different options weigh in. However, as important as the professional skill and knowledge might be, the preferences of each individual patient will also influence the final decision. The subjective meaning (“the illness”) of the situation (“the disease”) will vary among patients. Only the patient is the expert on how he or she feels about keeping a tooth, with or without retreatment, or perhaps extracting it, as well as which symptoms are tolerable, which risks are worth taking, and what costs are acceptable.

8.7.8 Modern Times: Improved Outcomes

During the last 20-year period, clinical endodontics has undergone a technological development of rare unprecedented proportions. Rotary instrumentation alloys have facilitated the painstaking work of removing old root fillings. Super-flexible properties of nickel-titanium instruments allow root canals to be successfully instrumented in a predictable way.

An equally significant addition to the endodontic armamentarium is the operating microscope. With its help, previously untreated parts of the root canal system can be visualized during both surgical and nonsurgical retreatments. Parallel with the increasing use of the operating microscope, a wide range of specialized instruments have been developed, primarily in connection with surgical endodontics. In addition, the introduction of ultrasonic instruments has further improved treatment options.

Much effort has also been expended on trying to develop new materials for safer retrograde sealing of the root canal. Alternatively, technological achievements have significantly changed the clinical routine of endodontic retreatment procedures.

In environments of clinical excellence, nonsurgical as well as surgical retreatments have shown favorable outcomes on the periapical tissues of “endodontic failures” [15, 48, 49]. It is likely that more root-filled teeth with apical periodontitis can be successfully treated surgically compared with reports from that before microsurgical techniques were used [15, 50]. Frequency of periapical healing after retreatment has been reported to reach approximately 80–90 % for both methods [15, 48]. High-quality clinical studies of long-term follow-up of teeth that have undergone surgical or retreatment are still missing.

8.7.9 Endodontic Retreatment: Need for Research

In the future, there is need for more research on endodontic retreatment methods as to whether they are effective and result in long-term tooth survival. In this context, it is also important to evaluate the alternatives to retreatment, extraction, and replacement by a tooth-supporting bridge or an implant from the perspective of quality of life and cost effectiveness [2, 9].

8.8 Conclusion

8.8.1 Short Answers to Clinical Questions

This chapter on molar endodontics shows that there is a considerable documentation gathered through the years about the methods that are used for preventing and treating diseases originating from the pulp and periradicular tissues. From the bulk of information, it can be concluded that various forms of endodontic treatments have saved and continue to save billions of molar teeth afflicted by caries or other insults.

Based on current best empirical and scientific knowledge, the following general short answers to “the clinical questions” may be appropriate:

-

What will happen to my tooth and me if pulpitis or apical periodontitis is left untreated?

-

The tooth may stay asymptomatic for a long time, but there is also a risk of periods of pain and, in a worst-case scenario, local spread of infection.

-

-

What different treatment options do I have if I decide to keep my tooth?

-

If the pulp is still vital, there are often reliable methods that can be used to try to save the integrity of the pulp and avoid root canal treatment. However, if pulp is seriously injured, which is very difficult to predict, pain or pulp necrosis may occur. In such a case, root canal treatment may be necessary.

-

-

After treatment, will my symptoms disappear?

-

After treatment, there may be a short period of postoperative pain, but if endodontic procedures are performed according to a high standard protocol your symptoms will almost invariably disappear. Approximately 95 % of root-filled teeth are asymptomatic after a postoperative period of 6 months.

-

-

How does the disease and treatment affect my risk of losing the tooth?

-

The risk of losing a tooth with severe injury to the pulp is higher than for a healthy tooth, in particular, if the pulp vitality is lost and there is a need for root canal treatment. But if properly treated and restored, approximately 90 % of root-filled teeth survive 10 years or more.

-

-

Will treatment cure pulpitis or apical periodontitis?

-

Yes, using current methods used in endodontics, in 80 –90 % of the cases, no signs of disease will be present at a standard clinical and radiographic checkup carried out a few years after treatment.

-

-

Is there a risk of persistence or relapse of disease?

-

In about 10 % of root canal treated cases, signs of disease may persist over time. If your restoration of the tooth is lost or if endodontic procedures are inadequately performed, disease may also relapse.

-

-

What will be my options, if persistence or relapse does occur?

-

In cases with persistent disease, surgical or nonsurgical retreatment performed by skilled specialists using modern armamentarium is able to cure the disease in about 80–90 % of the cases.

-

-

Would it be a better idea to take the tooth out?

-

In most cases not. But if the tooth is afflicted by periodontal disease or the remaining tooth substance does not provide conditions for a high-quality restoration, it might be a better idea.

-

-

If so, can it be replaced?

-

In the majority of cases, a lost tooth can be replaced by an implant or a fixed prosthesis.

-

8.8.2 Knowledge Gaps

There are few clinical studies of high scientific quality within the field of endodontics. Consequently, there are many knowledge gaps [9]. Further clinical studies with high quality are necessary to give our patients less vague answers to the following questions:

-

In a situation with a tooth with a vital pulp that is afflicted by deep caries, is it better to preserve the pulp vitality rather than to perform pulpectomy and root filling?

-

Is it more cost-effective in long term to have a root canal treatment and restoration rather than to extract the tooth and replace it with a fixed prosthesis or an implant?

-

Which specific treatment factors explain why endodontic treatments do not achieve an optimal outcome, that is, get extracted, remain painful, develop or have persistent apical periodontitis?

-

Will root-filled teeth survive long term, and what factors influence the loss of endodontically treated teeth?

-

How often will a root-filled tooth with persistent but asymptomatic periapical inflammation result in the occurrence of pain and swelling?

-

Which are the prognostic factors to predict an exacerbation of asymptomatic periapical inflammation, particularly in a root-filled tooth?

-

Are there any risks to general health when teeth with a periodical inflammatory process remain untreated?

References

Ng YL, Mann V, Rahbaran S, Lewsey J, Gulabivala K. Outcome of primary root canal treatment: systematic review of the literature – part 1. Effects of study characteristics on probability of success. Int Endod J. 2007;40:921–39.

Torabinejad M, Anderson P, Bader J, Brown LJ, Chen LH, Goodacre CJ, Kattadiyil MT, Kutsenko D, Lozada J, Patel R, Petersen F, Puterman I, White SN. Outcomes of root canal treatment and restoration, implant-supported single crowns, fixed partial dentures, and extraction without replacement: a systematic review. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;98(4):285–311.

Del Fabbro M, Taschieri S, Testori T, Francetti L, Weinstein RL. Surgical versus non-surgical endodontic re-treatment for periradicular lesions (Review). The Cochrane Collaboration and published in the Cochrane Library. 2008;(4).

Ng YL, Mann V, Rahbaran S, Lewsey J, Gulabivala K. Outcome of primary root canal treatment: systematic review of the literature – part 2. Influence of clinical factors. Int Endod J. 2008;41:6–31.

Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K. Outcome of secondary root canal treatment: a systematic review of the literature. Int Endod J. 2008;41(12):1026–46.

Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K. Tooth survival following non-surgical root canal treatment: a systematic review of the literature. Int Endod J. 2010;43(3):171–89.

Nixdorf DR, Moana-Filho EJ, Law AS, McGuire LA, Hodges JS, John MT. Frequency of persistent tooth pain after root canal therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod. 2010;36:224–30.

Torabinejad M, Corr R, Handysides R, Shabahang S. Outcomes of nonsurgical retreatment and endodontic surgery: a systematic review. J Endod. 2009;35:930–7.

Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment. Methods of diagnosis and treatment in endodontics—a systematic review. 2010; Report nr 203:1–491. http://www.sbu.se.

Aguilar P, Linsuwanont P. Vital pulp therapy in vital permanent teeth with cariously exposed pulp: a systematic review. J Endod. 2011;37(5):581–7.

Gillen BM, Looney SW, Gu LS, Loushine BA, Weller RN, Loushine RJ, Pashley DH, Tay FR. Impact of the quality of coronal restoration versus the quality of root canal fillings on success of root canal treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod. 2011;37:895–902.

Petersson A, Axelsson S, Davidson T, Frisk F, Hakeberg M, Kvist T, Norlund A, Mejàre I, Portenier I, Sandberg H, Tranaeus S, Bergenholtz G. Radiological diagnosis of periapical bone tissue lesions in endodontics: a systematic review. Int Endod J. 2012;45(9):783–801.

Bergenholtz G, Axelsson S, Davidson T, Frisk F, Hakeberg M, Kvist T, Norlund A, Petersson A, Portenier I, Sandberg H, Tranæus S, Majare I. Treatment of pulps in teeth affected by deep caries- a systematic review of the literature. Singapore Dent J. 2013;34:1–12.

Ricketts D, Lamont T, Innes NP, Kidd E, Clarkson JE. Operative caries management in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(3):CD003808.

Tsesis I, Rosen E, Taschieri S, Telishevsky Strauss Y, Ceresoli V, Del Fabbro M. Outcomes of surgical endodontic treatment performed by a modern technique: an updated meta-analysis of the literature. J Endod. 2013;39(3):332–9.

Kirkevang LL, Vaeth M, Wenzel A. Ten-year follow-up observations of periapical and endodontic status in a Danish population. Int Endod J. 2012;45(9):829–39.

Whitworth JM, Myers PM, Smith J, Walls AW, McCabe JF. Endodontic complications after plastic restorations in general practice. Int Endod J. 2005;38:409–16.

Gesi A, Hakeberg M, Warfvinge J, Bergenholtz G. Incidence of periapical lesions and clinical symptoms after pulpectomy – a clinical and radiographic evaluation of 1- versus 2-session treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101(3):379–88.

Engström B, Lundberg M. The correlation between positive culture and the prognosis of root canal therapy after pulpectomy. Odontol Revy. 1965;16:193–203.

Asgary S, Eghbal MJ, Ghoddusi J, Yazdani S. One-year results of vital pulp therapy in permanent molars with irreversible pulpitis: an ongoing multicenter, randomized, non-inferiority clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:431–9.

Andreasen JO, Bakland LK. Pulp regeneration after non-infected and infected necrosis, what type of tissue do we want? A review. Dent Traumatol. 2012;28(1):13–8.

Strindberg LZ. The dependence of the results of pulp therapy on certain factors. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 1956;14 (Suppl 21).

Molven O, Halse A, Fristad I, MacDonald-Jankowski D. Periapical changes following root-canal treatment observed 20–27 years postoperatively. Int Endod J. 2002;35:784–90.

Ørstavik D. Time-course and risk analyses of the development and healing of chronic apical periodontitis in man. Int Endod J. 1996;29:150–5.

Brynolf I. Histological and roentgenological study of periapical region of human upper incisors. Odontologisk Revy. 1967;18 (Suppl 11).

Wu MK, Shemesh H, Wesselink PR. Limitations of previously published systematic reviews evaluating the outcome of endodontic treatment. Int Endod J. 2009;42:656–66.

Ørstavik D, Kerekes K, Eriksen HM. The periapical index: a scoring system for radiographic assessment of apical periodontitis. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1986;2:20–34.

Bender IB, Seltzer S, Soltanoff W. Endodontic success- a reappraisal of criteria. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;22:780–802.

Friedman S, Mor C. The success of endodontic therapy – healing and functionality. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2004;32(6):493–503.

Wu MK, Wesselink P, Shemesh H. New terms for categorizing the outcome of root canal treatment. Int Endod J. 2011;44:1079–80.

Pak JG, Fayazi S, White SN. Prevalence of periapical radiolucency and root canal treatment: a systematic review of cross-sectional studies. J Endod. 2012;38(9):1170–6.

Van Nieuwenhuysen JP, Aouar M, D’Hoore W. Retreatment or radiographic monitoring in endodontics. Int Endod J. 1994;27(2):75–81.

Yu VS, Messer HH, Yee R, Shen L. Incidence and impact of painful exacerbations in a cohort with post-treatment persistent endodontic lesions. J Endod. 2012;38:41–6.

Lockhart PB, Bolger AF, Papapanou PN, et al.; on behalf of the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease, and Council on. Periodontal disease and atherosclerotic vascular disease: does the evidence support an independent association? A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:2520–44.

Wulff HR, Pedersen SA, Rosenberg R. Philosophy of medicine: an introduction. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1990.

Hofmann B. On the triad disease, illness and sickness. J Med Philos. 2002;27:651–73.

Hofmann BM, Eriksen HM. The concept of disease: ethical challenges and relevance to dentistry and dental education. Eur J Dent Educ. 2001;5:2–8; discussion 9–11.

Kvist T, Heden G, Reit C. Endodontic retreatment strategies used by general dental practitioners. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97:502–7.

Kvist T, Reit C. The perceived benefit of endodontic retreatment. Int Endod J. 2002;35:359–65.

Kvist T. Endodontic retreatment. Aspects of decision making and clinical outcome. Swed Dent J Suppl. 2001;144:1–57.

Petersson K, Håkansson R, Håkansson J, Olsson B, Wennberg A. Follow-up study of endodontic status in an adult Swedish population. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1991;7:221–5.

Bahrami G, Væth M, Kirkevang LL, Wenzel A, Isidor F. Risk factors for tooth loss in an adult population: a radiographic study. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:1059–65.

Vire DE. Failure of endodontically treated teeth: classification and evaluation. J Endod. 1991;17(7):338–42.

Landys Borén D, Jonasson P, Kvist T. Long-term survival of endodontically treated teeth at a public dental specialist clinic. J Endod. 2015;41:176–81.

Nair PN. New perspectives on radicular cysts: do they heal? Int Endod J. 1998;31:155–60.

Natkin E, Oswald RJ, Carnes LI. The relationship of lesion size to diagnosis, incidence, and treatment of periapical cysts and granulomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57:82–94.

Gorni FG, Gagliani MM. The outcome of endodontic retreatment: a 2-yr follow-up. J Endod. 2004;30:1–4.

Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K. A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment: part 1: periapical health. Int Endod J. 2011;44:583–609.

Zitzmann NU, Krastl G, Hecker H, Walter C, Waltimo T, Weiger R. Strategic considerations in treatment planning: deciding when to treat, extract, or replace a questionable tooth. J Prosthet Dent. 2010;104(2):80–91.

Setzer FC, Shah SB, Kohli MR, Karabucak B, Kim S. Outcome of endodontic surgery: a meta-analysis of the literature – part 1: comparison of traditional root-end surgery and endodontic microsurgery. J Endod. 2010;36(11):1757–65.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kvist, T. (2017). The Outcome of Endodontic Treatment. In: Peters, O. (eds) The Guidebook to Molar Endodontics. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-52901-0_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-52901-0_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-662-52899-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-662-52901-0

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)