Abstract

Team diversity and resilience play an important role in modern organizations. Although research on resilience in the organizational context has increased in recent years, studies addressing team resilience and its connection to team diversity remain scarce. In this chapter, the following three aspects will be addressed: 1) the definition and conceptualization of resilience and diversity; 2) the relationship between team diversity and resilience; and 3) the way to develop resilience in diverse teams. From a process-oriented perspective, an integrated model along with an overview of resilience-enhancing factors for diverse teams will be presented. This chapter thus provides a conceptual foundation for future research and gives an overview of the useful insights into successful resilience-enhancing practices in organizations.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In today’s business world, organizations and their members have been frequently confronted with adverse situations and unexpected transformative events. In the light of these challenges, resilience as the capacity to successfully cope with adversity is a fundamental and necessary quality in the organizational context (Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011). As work in most organizations occurs in teams that are often used to dealing with complex and critical situations entailing a high demand for risks, scholars focused on how teams develop resilience (Hartwig et al. 2020). However, although research on resilience in the organizational context has increased sharply in recent years (Duchek 2020; Linnenluecke 2017; Williams et al. 2017), only a few scholars (e.g., Alliger et al. 2015; Stoverink et al. 2018) have provided deeper insight into resilience at the team level.

Considering these developments, another important aspect of modern organizations is the increased diversity that their members face (van Knippenberg and Schippers 2007). Previous research describes diversity as a team characteristic that can refer to various attributes such as personal or work-related characteristics, which can be both beneficial and challenging (van Knippenberg er al. 2004; van Knippenberg and Schippers 2007; Joshi and Roh 2009; Williams and O’Reilly 1998). Although recent research suggests a potential link between diversity and resilience (Bui et al. 2019; Duchek et al. 2020), studies on diversity and its connection to resilience in organizations and teams have remained limited.

This chapter aims to combine these two concepts and provide insight gleaned from the recent literature by discussing three specific aspects from a process-oriented perspective. The discussion starts with the definition and conceptualization of both resilience and diversity in the organizational context, particularly at the team level. The next section examines the role of diversity and its potential challenges and benefits for team resilience. Finally, this chapter presents an integrated model providing an overview of the major factors enhancing resilience in diverse teams. As such, this chapter offers a novel lens to reinterpret previous literature though conceptual synthesis of diversity and resilience-related literature. Thus, it provides a conceptual foundation for future research and provides an overview of useful insight into successful resilience-enhancing practices of diverse teams that organizations, teams, and their leaders can use to improve their resilience capabilities.

2 Team Resilience

The word resilience originates from the Latin verb resilire, which means “to bounce back” (Amaral et al. 2015). Although the term appears in numerous disciplines, it has roots in material sciences, in which it describes a material’s elasticity in terms of its clamping force and hardiness (e.g., Snowdon 1958). In the past decade, various research disciplines adopted the resilience concept, including ecology (e.g., Gunderson 2000; Holling 1973), engineering (e.g., Hollnagel et al. 2006), and psychology (e.g., Fletcher and Sarkar 2013; Werner and Smith 2001). Recently, the concept drew increased attention in the organizational context (Linnenluecke 2017; Williams et al. 2017) and is described as an important quality of individuals, teams, and organizations in dealing with adversity (Sutcliffe and Vogus 2003; Williams et al. 2017).

In the organizational context, researchers generally explore resilience from two perspectives. While prior studies offer a more static, reaction-oriented understanding of resilience (e.g., Horne and Orr 1997; Mallak 1998), more recent research refers to resilience as a dynamic process (e.g., Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2012; McManus et al. 2008; Sutcliffe and Vogus 2003; Williams et al. 2017) and provides more insight into the underlying process-related resilience elements (e.g., Duchek 2020; Lengnick-Hall and Beck 2005, 2009; Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011). From a process-oriented perspective, resilience can be defined as the “ability to anticipate potential threats, to cope effectively with adverse events, and to adapt to changes” (Duchek 2020, p. 220). This definition suggests that the resilience process can be divided into three stages (before, during, and after adversity) built upon the underlying process-related capabilities of anticipation, coping, and adaptation (Duchek 2020; Duchek et al. 2020).

In line with general research in the organizational context, only a few scholars (e.g., Alliger et al. 2015; Gucciardi et al. 2018; Stoverink et al. 2018) have provided deeper insight into resilience at the team level. Building on the process-oriented perspective, the underlying resilience capabilities and behaviors needed to successfully complete the resilience process stages may be observed at the team level. For example, Alliger et al. (2015) identified some of these characteristics such as minimizing behavior to anticipate and prepare before adversity, managing behavior to cope with major challenges during adversity, and mending behavior to learn and reflect after adversity. Recent research also argues that internal team characteristics can influence team resilience (Gucciardi et al. 2018), as can other factors such as leadership or training interventions (Alliger et al. 2015; Flint-Taylor and Cooper 2017; Maynard and Kennedy 2016; Robertson et al. 2015). This chapter focuses on team resilience from the process-oriented perspective and provides insight on the factors that can enhance team resilience in the context of diverse teams.

3 Team Diversity

The word diversity derives from the Latin word diversus, which means “various” (Thompson and Cuseo 2015). Although different fields examine the potential role of diversity (e.g., Ecology Adger 2000, 2006; Holling 1973 and Computer Science, Borbor 2019), little is known about how diversity is related to resilience in teams and organizations, and if such a relationship exists (see e.g., Duchek et al. 2020). A general argument to connect resilience and diversity could be Ashby’s (1956) law of requisite variety, which states that “variety within a system must be at least as great as the environmental variety against which it is attempting to regulate itself” (Buckley, 1968, p. 495; see also Duchek et al. 2020; Hong and Page 2004). In this sense, the system (e.g., team) has broad access to different resources due to the heterogeneity of the system components (e.g., team members), which makes it possible to develop diverse options, ideas, and possibilities for action (Hong and Page 2004; Weick 1995). However, this connection also depends on the meaning of team diversity and the balance between the differences and similarities of individual perspectives within a team.

In the organizational context, team diversity can be defined as “the distribution of differences among the members of a unit with respect to a common attribute” (Harrison and Klein 2007, p. 1200). In this sense, diversity can be considered as a team-level construct and serves as an umbrella term for the various dimensions and types of diversity, such as personal or functional attributes. Personal attributes include personality and demographic attributes in terms of social-category classifications (e.g., gender, age, race or religion), whereas, functional attributes concern knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) related to the work environment (Bui et al. 2019; Gucciardi et al. 2018; Williams and O’Reilly 1998). In terms of diversity in KSAs, some scholars highlight the potential role of diversity in team resilience within organizations (e.g., Gomes et al. 2014; Sutcliffe and Vogus 2003). For example, Sutcliffe and Vogus (2003) argue that experiential diversity helps teams respond to the environment and cope with adversity better. Diversity in the team’s background and expertise expands its collective knowledge base, and consequently its repertoire of responses to crises or challenges (Gomes et al. 2014). Therefore, team diversity should have valuable potential to enhance team resilience.

Despite this potential, benefits of diversity may vary across teams. A closer look at the diversity literature shows that team diversity can be both beneficial and challenging and is often called a double-edged sword (van Knippenberg et al. 2004; Joshi and Roh 2009; Williams and O’Reilly 1998). From previous diversity literature, this dynamic has been explained from two perspectives. From the information elaboration perspective, team diversity may lead to a rich pool of knowledge, ideas, and work approaches that in turn can positively influence problem-solving and decision-making and can help teams deal with challenging tasks and adverse circumstances (van Knippenberg and Schippers 2007; Williams and O’Reilly 1998). In contrast, from the social categorization perspective, team diversity may limit within-unit integration and, therefore, may be considered a source of intergroup conflicts, thereby threatening the team’s well-being and success (e.g., Horwitz and Horwitz 2007; van Knippenberg and Schippers 2007). Consequently, we can assume that diversity should be considered both a challenge and a benefit, and that the resilience of teams depends on their ability to use and manage diversity effectively (Duchek et al. 2020; Guillaume et al. 2017; Nishii et al. 2018). Taking this into consideration, a more nuanced understanding is needed to fully grasp the interplay between diversity and resilience.

4 Team Diversity and Resilience: An Integrated Model

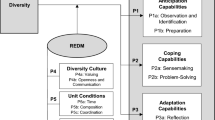

A process-oriented perspective of resilience capabilities has been applied to develop an integrated model of resilience for diverse teams (Alliger et al. 2015; Duchek 2020; Duchek et al. 2020). The central part of this model (Fig. 1) illustrates the three stages of the resilience process, along with the major resilience capabilities. We can consider team diversity as an antecedent for team resilience that either improves (from the information elaboration perspective) or hinders (from the social categorization perspective) team resilience capabilities. Teams develop resilience capabilities by engaging in the underlying resilience-enhancing behaviors, such as planning and preparation; communication and integration; reflection and learning. Teams can also enhance their potential for resilience capabilities using specific individual, team, and contextual resilience-enhancing factors. The resilience process results in positive outcomes, which represent the beneficial effects or positive consequences of this process in terms of both performance and the well-being of their team members. In the following section, the proposed model will be discussed in the context of the existing literature and with a focus on the key factors that can enhance resilience capabilities of diverse teams.

4.1 Team Diversity and Resilience Capabilities

Team diversity can either improve or hinder team resilience capabilities (Duchek et al. 2020). Specifically, from the perspective of information elaboration, diverse teams enjoy a diverse set of individual KSAs. In this way team diversity can then positively shape the emergence of team resilience (Duchek et al. 2020; Gucciardi et al. 2018). In stage one, diverse knowledge may help anticipate critical developments; in stage two, diverse skills and abilities can increase the possibility of coping with an acute situation; in stage three, different perspectives can help teams to better adapt and learn from experiences (Duchek et al. 2020). However, from the perspective of social categorization, differences in teams can hinder the integration processes within teams and may even foster intergroup conflict, which in turn leads to negative outcomes (Duchek et al. 2020; van Knippenberg et al. 2004; Williams and O’Reilly 1998). In that sense, the extent of resilience of diverse teams depends on how well they can overcome the negative effects of diversity and how they fare in improving their resilience capabilities. In the following sections, the underlying team-related behaviors, and resilience-enhancing factors for supporting and developing resilience capabilities in diverse teams are illustrated.

4.2 Resilience-Enhancing Behaviors

Three underlying resilience-enhancing behaviors that could support teams in cultivating resilience capabilities: planning and preparation, communication and cooperation, and reflection and learning can be identified based on the previous literature.

Planning and preparation: In the first stage of developing anticipation capabilities, diverse teams can enhance their resilience capabilities by better planning and preparing for potential challenges (Alliger et al. 2015). A close look at team-related behaviors shows that teams need to raise awareness about their current resources, improve planning, and prepare future response-oriented abilities to minimize negative developments and improve the potential benefits of diversity (Alliger et al. 2015; Glowinski et al. 2016; Stoverink et al. 2018). Such endeavors may involve a range of preparation-focused activities, including simulation or scenario-building training (Gomes et al. 2014; Pollock et al. 2003) by discussing hypothetical scenarios to develop contingency plans for adverse events (Alliger et al. 2015). Moreover, diverse teams can engage in general team development activities to help them to build a sense of diverse skills and abilities within the team. Finally, participating in specific resilience-enhancing interventions may help develop resilience capabilities and resources (Lundberg and Rankin 2014; Robertson et al. 2015).

Communication and cooperation: In the second stage, to overcome social categorization barriers, diverse teams must improve their interpersonal processes with strong communication and cooperation behaviors, thereby enhancing their coping capabilities (Alliger et al. 2015; Amaral et al. 2015; Meneghel et al. 2016). Recent research provides meta-analytic support for the positive effect of communication on team performance and resilience, particularly for diverse teams (Bui et al. 2019). For example, open communication allows teams to strengthen positive relationships (Carmeli et al. 2013), which are particularly useful in terms of support in critical or adverse situations. In addition, strong cooperation among team members is an important resilience-enhancing behavior (Alliger et al. 2015; Stoverink et al. 2018). In the case of diverse teams, team members need to support each other’s ideas, coordinate the completion of tasks according to their individual resources, and share information or different perspectives to generate the best possible solution, especially during critical situations or adversity (Morgan Fletcher and Sarkar 2013).

Reflection and learning: The third stage of the process essentializes reflection and learning as important behavioral components. A close look at team-related practices shows that reflection and learning are resilient behaviors vital for teams, which help their members improve their resilience capabilities and become better prepared for future challenges (Alliger et al. 2015; Gucciardi et al. 2018; Stoverink et al. 2018). Such behaviors may include collective reflection or debriefing activities (Alliger et al. 2015). Research on team-based reflection provides meta-analytic support for the idea that debriefing positively affects team performance (Tannenbaum and Cerasoli 2013). Another important aspect is learning behavior. Morgan et al. (2013) find that more resilient teams had a greater orientation toward learning and viewed setbacks as learning opportunities. By extension, such behaviors may help diverse teams include different perspectives, enhance their behavioral repertoire, and consequently improve their collective resilient behaviors for the future. In this way, teams will not only bounce back from difficulties but will have the opportunity to build resilience, and thus, emerge stronger as a team.

4.3 Resilience-Enhancing Factors

Apart from resilience-enhancing behaviors, resilience-enhancing factors can be grouped into the individual, team, and contextual factors according to the previous literature.

Individual factors: At the individual level, individual attitudes towards diversity of team members have been reported to be important (van Knippenberg et al. 2004). Gucciardi et al. (2018) suggest that resilience processes in teams may emerge from team members combining their KSAs at the individual level. For example, a team member’s contribution to effective communication and integration during adverse events may depend on his or her capacity to engage in interactive processes. In case of diverse teams, team members need to have positive attitudes toward diversity, which help them engage in more effective resilient behaviors (Homan et al. 2010; van Knippenberg and Schippers 2007). In this sense, previous literature has shown that individuals who value diversity in a team identify more strongly with their diverse team (van Knippenberg et al. 2007) and tend to perceive team members as individuals and are less likely to categorize them into subgroups (Homan et al. 2010). This is particularly important in view of the fact that subgroup categorization is one of the main mechanisms for the potential negative effects of diversity.

Team factors: At the team level, one of the key factors in enhancing resilience is team training (e.g., Alliger et al. 2015; Robertson et al. 2015). To foster a team’s resilience capabilities in diverse teams, diversity training should be considered. Diversity training is a program designed to facilitate positive intergroup interaction, reduce prejudice and discrimination, and encourage dissimilar individuals to work together (Bezrukova et al. 2012; Carnevale and Stone 1994; Pendry et al. 2007; Roberson et al. 2001). Within this broad understanding, two types of diversity training can be distinguished: awareness training and skill-building training. Awareness training aims to raise awareness of diversity-related issues and help increase sensitivity and general knowledge of diversity (Bezrukova et al. 2012; Roberson et al. 2001). Thus, it provides knowledge and promotes positive attitudes toward diversity. Skill-building training seeks to promote behavioral capabilities by providing different supporting tools for managing diversity (Bezrukova et al. 2012; Roberson et al. 2001). In addition to providing information and increasing motivation, diversity training aims to change behavior and has the potential to promote resilience in diverse teams, largely because it helps teams identify the necessary behavioral patterns for utilizing the expanded pool of knowledge and dealing constructively with emerging conflicts and difficulties (e.g., van Knippenberg et al. 2004).

Contextual factors: Among the resilience contextual factors, leadership was identified as one of the key factors to enhance resilience (Hartwig et al. 2020). Leaders can proactively accrue important team resources and set the course for positive adjustment during adverse events (Sutcliffe and Vogus 2003). Research suggests that transformational leadership may be one potential resilience-enhancing leadership style (Dimas et al. 2018), especially for diverse teams (Duchek et al. 2020; Homan et al. 2020). This leadership style is associated with leader’s behavior that aims to inspire and motivate employees, thereby leading to greater resilience among team members (Hartwig et al. 2020; Sommer et al. 2016). In general, leadership styles characterized by healing relationships, increasing trust, and resolving conflicts are best suited to access the resilience-enhancing potential of diverse teams because such styles may limit social categorization and foster motivation to support team processes (e.g., Homan and Greer 2013; van Knippenberg and Schippers 2007). Besides a leader’s style, a leader’s specific competencies are important in understanding and supporting resilience-enhancing behaviors in diverse teams. For example, according to Homan et al. (2020) a leader’s competencies require cognitive understanding, social perceptiveness, and behavioral flexibility, and thus can support resilience-enhancing behaviors of diverse teams.

5 Summary

This chapter offered an overview of the current state of the literature on team diversity and resilience in organizations. Building on a process-oriented perspective, an integrated model of resilience for diverse teams has been provided. First, team diversity can be related to resilience though the various resilience capabilities underlying the three stages of the resilience process (i.e., anticipation, coping, and adaptation). In this view, team diversity can be considered as an antecedent for team resilience that may either improve or hinder team resilience capabilities depending on social categorization and information elaboration perspectives. Second, three underlying resilience-enhancing behaviors that could support teams in cultivating resilience capabilities have been identified based on the previous literature. In particular, teams need to improve their planning and preparation, communication and cooperation, and reflection and learning behaviors. Third, an overview of key individual, team, and contextual resilience-enhancing factors have been provided. To support resilience-enhancing developments, individual attitudes, team training, and leadership should be considered. In future research, scholars could apply the provided model and focus on specific topics or elements of resilience-enhancing behaviors or factors in more detail. In sum, this chapter may facilitate future research and provide important insight into the effective promotion and management of resilience in today’s organizations.

References

Adger, W.N. (2000): Social and ecological resilience: are they related? Progress in human geography, 24(3), 347–364.

Adger, W.N. (2006): Vulnerability. Global environmental change, 16(3), 268–281.

Alliger, G.M., Cerasoli, C.P., Tannenbaum, S.I., Vessey, W.B. (2015): Team resilience: How teams flourish under pressure. Organizational Dynamics, 44(3), 176–184.

Amaral, A., Fernandes, G., Varajao, J. (2015): Identifying useful actions to improve team resilience in information systems projects. Procedia Computer Science, 64, 1182–1189.

Bezrukova, K., Jehn, K.A., Spell, C.S. (2012): Reviewing diversity training: Where we have been and where we should go. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 11(2), 207–227.

Borbor, D., Wang, L., Jajodia, S., Singhal, A. (2019): Optimizing the network diversity to improve the resilience of networks against unknown attacks. Computer Communications, 145, 96–112.

Buckley W. (1968): Society as a complex adaptive system. In: Buckley, W. (ed.): Modern System Research for the Behavioral Scientist, Aldine: Chicago. 490–513.

Bui, H., Chau, V.S., Degl'Innocenti, M., Leone, L., Vicentini, F. (2019): The resilient organisation: A meta‐analysis of the effect of communication on team diversity and team performance. Applied Psychology, 68(4), 621–657.

Carmeli, A., Friedman, Y., Tishler, A. (2013): Cultivating a resilient top management team: The importance of relational connections and strategic decision comprehensiveness. Safety Science, 51, 148–159.

Carnevale, A.P., Stone, S.C. (1994): Diversity beyond the golden rule. Training & Development, 48(10), 22–40.

Dimas, I.D., Rebelo, T., Lourenço, P.R., Pessoa, C.I.P. (2018): Bouncing back from setbacks: On the mediating role of team resilience in the relationship between transformational leadership and team effectiveness. The Journal of Psychology, 152(6), 358–372.

Duchek, S. (2020): Organizational resilience: A capability-based conceptualization. Business Research, 13(1), 215–246.

Duchek, S., Raetze, S., Scheuch, I. (2020): The role of diversity in organizational resilience: a theoretical framework. Business Research, 13(2), 387–423.

Fletcher, D., Sarkar, M. (2013): Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist, 18(1), 12–23.

Flint-Taylor, J., Cooper, C.L. (2017): Team resilience: Shaping up the challenges ahead. In: M. Crane (Ed.): Manage for resilience: A practical guide for employee well-being and organizational performance. New York, NY: Routledge. 129–149.

Glowinski, D., Bracco, F., Chiorri, C., Grandjean, D. (2016): Music ensemble as a resilient system. Managing the unexpected through group interaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1548.

Gomes, J.O., Borges, M.R., Huber, G.J., Carvalho, P.V.R. (2014): Analysis of the resilience of team performance during a nuclear emergency response exercise. Applied Ergonomics, 45(3), 780–788.

Gucciardi, D.F., Crane, M., Ntoumanis, N. et al. (2018): The emergence of team resilience: A multilevel conceptual model of facilitating factors. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 91(4), 729–768.

Guillaume Y.R., Dawson J.F., Otaye-Ebede L. et al. (2017): Harnessing demographic differences in organizations: What moderates the effects of workplace diversity? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(2), 276–303.

Gunderson, L.H. (2000). Ecological resilience—in theory and application. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 31(1), 425–439.

Hartwig, A., Clarke, S., Johnson, S., & Willis, S. (2020). Workplace team resilience: A systematic review and conceptual development. Organizational Psychology Review, 10(3-4), 169-200.

Harrison, D.A., Klein, K.J. (2007): What's the difference? Diversity constructs as separation, variety, or disparity in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1199–1228.

Holling, C.S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4(1), 1–23.

Hollnagel, E., Woods, D., Leveson, N. (Eds.) (2006): Resilience engineering: Concepts and precepts. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

Homan, A.C., Greer, L.L. (2013): Considering diversity: The positive effects of considerate leadership in diverse teams. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 16(1), 105–125.

Homan, A.C., Greer, L.L., Jehn, K.A., Koning, L. (2010): Believing shapes seeing: The impact of diversity beliefs on the construal of group composition. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 13(4), 477–493.

Homan, A.C., Gündemir, S., Buengeler, C., van Kleef, G.A. (2020): Leading diversity: Towards a theory of functional leadership in diverse teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(10), 1101.

Hong, L., Page, S.E. (2004): Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(46), 16385–16389.

Horne, J.F., Orr, J.E. (1997): Assessing behaviors that create resilient organizations. Employment Relations Today, 24(4), 29–39.

Horwitz, S.K., Horwitz, I.B. (2007): The effects of team diversity on team outcomes: A meta-analytic review of team demography. Journal of Management, 33(6), 987–1015.

Joshi, A., Roh, H. (2009): The role of context in work team diversity research: A meta-analytic review. Academy of Management Journal, 52(3), 599–627.

Lengnick-Hall, C.A., Beck, T.E. (2005): Adaptive fit versus robust transformation: How organizations respond to environmental change. Journal of Management, 31(5), 738–757.

Lengnick-Hall, C.A., Beck, T.E. (2009): Resilience capacity and strategic agility: Prerequisites for thriving in a dynamic environment. In: C. Nemeth, E. Hollnagel, S. Dekker (Eds.): Resilience engineering perspectives, 2, Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing.

Lengnick-Hall, C.A., Beck, T.E., Lengnick-Hall, M.L. (2011): Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 21(3), 243–255.

Linnenluecke, M.K. (2017): Resilience in business and management research: A review of influential publications and a research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(1), 4–30.

Linnenluecke, M.K., Griffiths, A. (2012): Assessing organizational resilience to climate and weather extremes: complexities and methodological pathways. Climatic Change, 113(3–4), 933–947.

Lundberg, J., Rankin, A. (2014): Resilience and vulnerability of small flexible crisis response teams: implications for training and preparation. Cognition, Technology & Work, 16(2), 143–155.

Mallak, L.A. (1998): Measuring resilience in health care provider organizations. Health Manpower Management, 24 (4), 148–152.

Maynard, M.T., Kennedy D.M. (2016): Team adaptation and resilience: What do we know and what can be applied to long-duration isolated, confined, and extreme contexts. TX: National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

McManus, S., Seville, E., Vargo, J., Brunsdon, D. (2008): Facilitated process for improving organizational resilience. Natural Hazards Review, 9(2), 81–90.

Meneghel, I., Salanova, M., Martinez, I.M. (2016): Feeling Good Makes Us Stronger: How Team Resilience Mediates the Effect of Positive Emotions on Team Performance. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17, 239–255.

Morgan, P.B., Fletcher, D., Sarkar, M. (2013): Defining and characterizing team resilience in elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(4), 549–559.

Nishii, L.H., Khattab, J., Shemla, M., Paluch, R.M. (2018): A multi-level process model for understanding diversity practice effectiveness. Academy of Management Annals, 12(1), 37–82.

Pendry, L.F., Driscoll, D.M., Field, S.C.T. (2007): Diversity training: Putting theory into practice. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80(1), 27–50.

Pollock, C., Paton, D., Smith, L.M., Violanti, J.M. (2003): Team resilience. In: D. Paton, J.M. Violanti, L.M. Smith (Eds.): Promoting capabilities to manage posttraumatic stress— Perspectives on resilience. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher. 74–102.

Roberson, L., Kulik, C.T., Pepper, M.B. (2001): Designing effective diversity training: Influence of group composition and trainee experience. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(8), 871–885.

Robertson, I.T., Cooper, C.L., Sarkar, M., Curran, T. (2015): Resilience training in the workplace from 2003 to 2014: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(3), 533–562.

Snowdon, J.C. (1958): The choice of resilient materials for anti-vibration mountings. British Journal of Applied Physics, 9(12), 461.

Sommer, S. A., Howell, J. M., & Hadley, C. N. (2016): Keeping positive and building strength: The role of affect and team leadership in developing resilience during an organizational crisis. Group & Organization Management, 41(2), 172–202.

Stoverink, A.C., Kirkman, B.L., Mistry, S., Rosen, B. (2018): Bouncing back together: Towards a theoretical model of work team resilience. Academy of Management Review, 45(2), 395–422

Sutcliffe, K.M., Vogus, T.J. (2003): Organizing for resilience. In: K.S. Cameron, J.E. Dutton, R.E. Quinn (eds.): Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline, San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. 94–110.

Tannenbaum, S.I., Cerasoli, C.P. (2013): Do team and individual debriefs enhance performance? A meta-analysis. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 55(1), 231–245.

Thompson, A., Cuseo, J.B. (2015): Introduction: Diversity. In S. Thompson (Eds.): Encyclopedia of diversity and social justice. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Van Knippenberg, D., Schippers, M.C. (2007). Work group diversity. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 515–541.

Van Knippenberg, D., De Dreu, C.K.W., Homan, A.C. (2004): Work group diversity and group performance: An integrative model and research agenda. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 1008–1022.

Weick, K.E. (1995): Sensemaking in organizations. London: Sage.

Werner, E.E., Smith, R.S. (2001): Journeys from childhood to midlife: Risk, resilience, and recovery. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Williams, K., O'Reilly, C. (1998): Demography and diversity in organizations: A review of 40 years of research. Research in Organizational Behavior, 20, 77–140.

Williams, T.A., Gruber, D.A., Sutcliffe, K.M., Shepherd, D.A., Zhao, E.Y. (2017): Organizational response to adversity: Fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Academy of Management Annals, 11(2), 733–769.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Scheuch, I. (2021). Team Diversity and Resilience in Organizations. In: Wink, R. (eds) Economic Resilience in Regions and Organisations. Studien zur Resilienzforschung. Springer, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-33079-8_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-33079-8_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN: 978-3-658-33078-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-658-33079-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)