Abstract

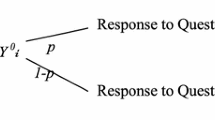

When it comes to deviant behavior and other sensitive topics, respondents in surveys tend either to refuse answering such sensitive questions or to tailor their answers in a socially desirable direction. This occurs by underreporting on negatively connoted behaviors or attitudes and by overreporting on positively connoted ones (be it deliberately or undeliberate). Thus, prevalence estimates of deviant traits are biased. Moreover, if the tendency to misreport is related to influencing factors of the deviant behavior or attitude under investigation, the correlations are biased as well.

In order to tackle the problems of nonresponse and misreporting to sensitive questions, survey methodology has come up with several special questioning techniques which mostly aim at anonymizing the interview situation and in doing so, to impose less burden on respondents when answering sensitive questions. Among the oldest proposed techniques is the sealed envelope technique (SET) for face-to-face interviews: Respondents are asked to fill out the “sensitive part” of the interview on a self-administered ballot and to seal it in a secret envelope that the interviewer does not open personally.

The aim of our paper is to investigate whether SET has methodological advantages as compared to classic direct questioning (DQ). The data stem from a “sensitive topic survey” among University students in the City of Mainz (Germany, n = 578). The sensitive questions selected for this evaluation pertain to sexual experiences and behavior.

Results show that—compared to direct questions—the sealed envelope technique has some advantages: It reduces misreporting of sensitive behavior; in particular, it helps certain subgroups (e.g. religious people) to overcome subjective barriers in answering sensitive questions accurately; it diminishes item nonresponse; and it lowers subjective feelings of uneasiness of interviewers and respondents when it comes to sensitive issues. The general conclusion is that the sealed envelope technique seems to be a helpful tool in gathering less biased data about sensitive behavior.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

19 May 2020

Die ursprüngliche digitale Version dieses Werkes wurde zu früh publiziert und wird durch die vorliegende korrigierte Version ersetzt.

Notes

- 1.

With respect to social desirability bias, rational choice theory focuses on three determinants of this type of misreporting (Stocké 2007b): 1) respondents’ social desirability (SD) beliefs, i.e. their perceptions of which answer is socially expected, 2) respondents’ need for social approval, and 3) respondents’ feeling of privacy in the interview situation.

- 2.

A third restriction imposed by the registration office was that the students selected were born between May and October. The interviewers did not know about this restriction and asked for the month (and year) of birth in their interviews. This enabled a check of interviewer reliability. Only three interviewers reported birth months outside the May-October range. The field work of these three interviewers was checked thoroughly, but without confirmation of serious cheating.

- 3.

Wording/framing techniques did not make much difference to direct questioning in general; the randomized response procedure used in our survey proved to deliver inconsistent and implausible results (for descriptive findings, see Preisendörfer 2008).

- 4.

Each of the 47 interviewers had an interviewer number. The randomization procedure used this number to determine which type of interview (direct/indirect) an interviewer had to conduct. This assignment of interviewers to questionnaire versions includes the risk to confound interviewer attributes and treatment (direct/indirect), but the randomization should control for this.

- 5.

For example, questions on whether respondents live in a regular partnership or what they consider important for living in a partnership (“love”, “fun”, “freedom”, etc.).

- 6.

From further inspection of the two cases it is difficult to tell whether the reported 100 sex partners are plausible values, misreporting, or a coding error.

- 7.

Confined to those living in a partnership, the mean of coital frequency in the last four weeks goes up to 8, and this corresponds with values obtained from other studies of coital frequency in partnership relations (e.g., Jasso 1985).

- 8.

Within research on social desirability, empirical studies have shown that often there is no consensus regarding which answer to a behavioral or attitudinal question is socially expected, i.e. corresponds to normative expectations (Stocké 2007a, b; Stocké and Hunkler 2007). Based on this finding of heterogeneous “SD beliefs,” it is only a short step to the assumption that SET effects vary for different subgroups of the population.

- 9.

This finding clearly contradicts other empirical studies having found that men report more sexual partners than women (Smith 1992; Tourangeau et al. 1997; Liljeros et al. 2001). We may speculate that our special sample of German university students could be responsible for this result. A widespread hypothesis about sex reporting is that men have a tendency towards overreporting whereas women have a tendency towards underreporting (Tourangeau et al. 1997, p. 355; Krumpal et al. 2018). However, in a recent study, Krumpal et al. (2018) do not find a clear pattern of gender-specific over- and underreporting of lifetime sexual partners, too.

- 10.

We also checked for interaction effects between the respondent’s and interviewer’s gender. We did not find any significant interaction effects with the exception of masturbation: If the interviewer is female and in SET mode only, the negative effect for female respondents is less pronounced as compared to a male interviewer.

- 11.

Note that the questions concerning one-night stands, sexual infidelity and homosexual contacts are formulated with the frame “ever engaged in.” Such a frame is normally less threatening than the frame “currently engaged in.” Moreover, these questions are simple yes/no questions as opposed to the other questions which ask—in a more demanding manner—for numbers and frequencies.

- 12.

With respect to sex questions, Tourangeau et al. (1997), for example, have demonstrated that self-administered questions (SAQs) produce higher levels of reporting. See, for example, Tourangeau and Yan (2007); Wolter (2012, pp. 57–61) for literature reviews regarding the effects of self-administration (and other survey modes) on response behavior.

References

Aquilino, W. S. (1998). Effects of interview mode on measuring depression in younger adults. Journal of Official Statistics, 14(1), 15–29.

Auspurg, K., & Hinz, T. (2014). Factorial survey experiments (quantitative applications in the social sciences 175). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Barnett, J. (1998). Sensitive questions and response effects: An evaluation. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 13(1–2), 63–76.

Barton, A. H. (1958). Asking the embarrassing question. Public Opinion Quarterly, 22(1), 67–68.

Becker, R. (2006). Selective responses to questions on delinquency. Quality & Quantity, 40(4), 483–498.

Becker, R., & Günther, R. (2004). Selektives Antwortverhalten bei Fragen zum delinquenten Handeln. Eine empirische Studie über die Wirksamkeit der „sealed envelope technique“ bei selbst berichteter Delinquenz mit Daten des ALLBUS 2000. ZUMA-Nachrichten, 54, 39–59.

Benson, L. E. (1941). Studies in secret-ballot technique. Public Opinion Quarterly, 5(1), 79–82.

Biemer, P. P., & Lyberg, L. E. (2003). Introduction to survey quality. Hoboken: Wiley-Interscience.

Bradburn, N. M., & Sudman, S. (1979). Improving interview method and questionnaire design. Response effects to threatening questions in survey research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cantril, H. (1940). Experiments in the wording of questions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 4(2), 330–332.

De Leeuw, E. D., & Edith, D. (2001). Reducing missing data in surveys: An overview of methods. Quality & Quantity, 35(2), 147–160.

Droitcour, J., Caspar, R. A., Hubbard, M. L., Parsley, T. L., Visscher, W., & Ezzati, T. M. (1991). The item count technique as a method of indirect questioning: A review of its development and a case study application. In P. P. Biemer, R. M. Groves, L. E. Lyberg, N. A. Mathiowetz, & S. Sudman (Hrsg.), Measurement errors in surveys (S. 185–210). New York: Wiley.

Esser, H. (1991). Die Erklärung systematischer Fehler in Interviews: Befragtenverhalten als „rational choice“. In R. Wittenberg (Hrsg.), Person—Situation—Institution—Kultur. Günter Büschges zum 65. Geburtstag (S. 59–78). Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Fox, J. A., & Tracy, P. E. (1986). Randomized response. A method for sensitive surveys: Vol. 07–058. Sage university paper series on quantitative applications in the social sciences. Newbury Park: Sage.

Hox, J. J., & Leeuw, E. D. D. (2002). The influence of interviewers’ attitude and behavior on household survey nonresponse: An international comparison. In R. M. Groves, D. A. Dillman, J. L. Eltinge, & R. J. A. Little (Hrsg.), Survey nonresponse (S. 103–120). New York: Wiley.

Jann, B., I. Krumpal, & F. Wolter (Ed.). (2019). Social desirability bias in surveys—collecting and analyzing sensitive data: vol. 13. mda—Methods, Data, Analyses.

Jasso, G. (1985). Marital coital frequency and the passage of time: Estimating the separate effects of spouses’ ages and marital duration, birth and marriage cohorts, and period influences. American Sociological Review, 50(2), 224–241.

Krosnick, J. A., Holbrook, A. L., Berendt, M. K., Carson, R. T., Michael Hanemann, W., Kopp, R. J., Mitchell, R. C., Presser, S., Ruud, P. A., Smith, V. K., Moody, W. R., Green, M. C., & Conaway, M. (2002). The impact of „no opinion“ response options on data quality. Non-attitude reduction or an invitation to satisfice? Public Opinion Quarterly, 66(3), 371–403.

Krumpal, I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity, 47(4), 2025–2047.

Krumpal, I., Jann, B., Korndörfer, M., & Schmukle, S. C. (2018). Item sum double-list technique: An enhanced design for asking quantitative sensitive questions. Survey Research Methods, 12(2), 91–102.

Lee, R. M. (1993). Doing research on sensitive topics. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Lensvelt-Mulders, G. J. L. M. (2008). Surveying sensitive topics. In E. D. de Leeuw, J. J. Hox, & D. A. Dillman (Hrsg.), International handbook of survey methodology (S. 461–478). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Liljeros, F., Edling, C. R., Nunes, L. A., Eugene Amaral, H., & Aberg, Y. (2001). The web of human sexual contacts. Nature, 411, 907–908.

Makkai, T., & McAllister, I. (1992). Measuring social indicators in opinion surveys: A method to improve accuracy on sensitive questions. Social Indicators Research, 27(2), 169–186.

Perry, P. (1979). Certain problems in election survey methodology. Public Opinion Quarterly, 43(3), 312–325.

Preisendörfer, P. (2008). Heikle Fragen in mündlichen Interviews: Ergebnisse einer Methodenstudie im studentischen Milieu (unpublished manuscript). Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz.

Preisendörfer, P., & Wolter, F. (2014). Who is telling the truth? A validation study on determinants of response behavior in surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 78(1), 126–146.

Rasinski, K. A., Willis, G. B., Baldwin, A. K., Yeh, W., & Lee, L. (1999). Methods of data collection, perceptions of risks and losses, and motivation to give truthful answers to sensitive survey questions. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13(5), 465–484.

Schnell, R. (1997). Nonresponse in Bevölkerungsumfragen. Ausmaß, Entwicklung und Ursachen. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Schnell, R., & Kreuter, F. (2005). Separating interviewer and sampling-point effects. Journal of Official Statistics, 21(3), 389–410.

Smith, T. W. (1992). Discrepancies between men and women in reporting number of sexual partners: A summary from four countries. Social Biology, 39(1–2), 203–211.

Stocké, V. (2004). Entstehungsbedingungen von Antwortverzerrungen durch soziale Erwünschtheit. Ein Vergleich der Rational-Choice Theorie und des Modells der Frame-Selektion. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 33(4), 303–320.

Stocké, V. (2007a). Determinants and consequences of survey respondents’ social desirability beliefs about racial attitudes. Methodology, 3(3), 125–138.

Stocké, V. (2007b). The interdependence of determinants for the strength and direction of social desirability bias in racial attitude surveys. Journal of Official Statistics, 23(4), 493–514.

Stocké, V., & Hunkler, C. (2007). Measures of desirability beliefs and their validity as indicators for socially desirable responding. Field Methods, 19(3), 313–336.

Sudman, S., & Bradburn, N. M. (1974). Response effects in surveys: A review and synthesis. Chicago: Aldine.

Sudman, S., & Bradburn, N. M. (1982). Asking questions. A practical guide to questionnaire design. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Tourangeau, R., Rasinski, K., Jobe, J. B., Smith, T. W., & Pratt, W. F. (1997). Sources of error in a survey on sexual behavior. Journal of Official Statistics, 13(4), 341–365.

Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. A. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tourangeau, R., & Smith, T. W. (1996). Asking sensitive questions. The impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Public Opinion Quarterly, 60(2), 275–304.

Tourangeau, R., & Yan, T. (2007). Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin, 133(5), 859–883.

Wolter, F. (2012). Heikle Fragen in Interviews. Eine Validierung der Randomized Response-Technik. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Wolter, F., & Herold, L. (2018). Testing the item sum technique (ist) to tackle social desirability bias. SAGE Research Methods Cases. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781526441928.

Wolter, F., & Laier, B. (2014). The effectiveness of the item count technique in eliciting valid answers to sensitive questions. An evaluation in the context of self-reported delinquency. Survey Research Methods, 8(3), 153–168.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, ein Teil von Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wolter, F., Preisendörfer, P. (2020). Let’s Ask About Sex: Methodological Merits of the Sealed Envelope Technique in Face-to-Face Interviews. In: Krumpal, I., Berger, R. (eds) Devianz und Subkulturen. Kriminalität und Gesellschaft. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-27228-9_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-27228-9_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN: 978-3-658-27227-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-658-27228-9

eBook Packages: Social Science and Law (German Language)