Abstract

Depression, anxiety, and other psychological issues are more prevalent among patients with chronic diseases such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) compared to the general population and patients in primary care settings. Nearly one out of four or five patients with kidney disease experiences a major depressive disorder (MDD), which is greater than the proportion with depression reported for other chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, or congestive heart failure. It is well established that the presence of either high scores on depressive symptom severity scales or a clinical diagnosis of MDD is associated with increased morbidity and mortality among patients with CKD or those treated with maintenance dialysis. Therefore, recognizing depressive symptoms, diagnosing MDD, and excluding other conditions such as anxiety, pain, somatic symptoms of uremia, dementia, and delirium are very important to develop appropriate management strategies for such patients. Validated tools can be used to screen for depressive symptoms, and a clinical diagnosis of depression should be confirmed in those who screen positive either by using a structured clinician-administered interview or by referral to mental health, based on complexity of the presentation and presence of comorbid psychiatric illnesses, such as bipolar disorders. Risk for suicide should be ascertained and triaged appropriately. Various pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions can be applied to treat MDD in patients with CKD, but data on safety and efficacy are limited. If antidepressant medications are considered, they should be initiated at a low dose and titrated up based on frequent monitoring to ensure tolerability and response to treatment.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Depressive Symptom

- Chronic Kidney Disease

- Major Depressive Disorder

- Major Depressive Disorder

- Chronic Kidney Disease Patient

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

FormalPara Before You Start: Facts You Need to Know-

Depression, anxiety, and other psychological disorders are prevalent in patients with CKD.

-

Patients with CKD commonly present with somatic symptoms, such as sleep disturbances, sexual dysfunction, low energy level, easy fatigability, and weight and appetite changes, which may be related to uremia and difficult to differentiate from depressive symptoms.

-

The presence of depressive symptoms and major depressive disorder predicts adverse clinical outcomes in patients with CKD.

-

Depression is a less commonly recognized problem in patients with CKD and ESRD.

-

Depression is often treated inadequately.

-

Clinicians need to know the nuances in recognizing, diagnosing, and treating depression in patients with CKD in order to improve adverse clinical outcomes and quality of life.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a constellation of symptoms that a patient experiences for 2 weeks or more, comprised of either depressed mood or anhedonia plus at least five of the nine Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria symptom domains [1] (Box 23.1). Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) experience decreased energy, poor appetite, and sleep disturbance commonly that may not necessarily reflect an episode of MDD but represent symptoms of uremia or burden of other comorbid illnesses, such as congestive heart failure. In addition, other symptom burdens, psychiatric conditions, or cognitive impairment experienced commonly by patients with advanced CKD or ESKD may be present such as anxiety, chronic pain, erectile dysfunction, dementia, and delirium that need to be differentiated from a depressive disorder [2]. It is even more challenging for clinicians to manage MDD in CKD and ESRD patients once it is identified due to limited data on safety and efficacy of antidepressant medications in this high-risk population, which leads to only a minority of such patients getting treated appropriately and adequately [2]. Pain, sexual dysfunction, and quality of life issues in patients with CKD are discussed in other chapters and will not be further discussed here.

-

1.

Depressed mood

-

2.

Loss of interest or pleasure (anhedonia)

-

3.

Appetite disturbance

-

4.

Sleep disturbance

-

5.

Psychomotor agitation or retardation

-

6.

Fatigue and tiredness

-

7.

Worthlessness, feeling like a burden, or guilty

-

8.

Difficulty concentrating

-

9.

Recurring thoughts of death or suicide

1 Prevalence of Depression in Patients with CKD

There is a high prevalence of depression in patients with chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and ESKD. The point prevalences of depression in the general population and the primary care setting are estimated to be 2–4 % and 5–10 %, respectively [2]. On the other hand, the point prevalences of depression in patients with chronic diseases such as post-myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (CHF), and ESKD on chronic dialysis are much higher at 16, 14, and 26 %, respectively [2].

A distinction must be made between the presence of depressive affect or depressive symptoms ascertained from patients by the use of self-report scales and a depressive disorder diagnosis (such as MDD) made by a physician using an interview. The majority of studies reporting the prevalence of depression in patients with CKD and ESKD used self-report questionnaires to assess depressive symptoms instead of reports by a physician or interview-based diagnosis. Unfortunately, the estimates by self-reported rating scales may overestimate the presence of MDD, particularly in patients with advanced CKD or ESKD treated with maintenance dialysis, given the overemphasis of the somatic symptoms of depression, such as appetite changes, sleep disturbance, and fatigue that are commonly present in such patients. This was illustrated in a recent meta-analysis [3], where the prevalence of depression in ESKD patients on maintenance dialysis when ascertained by self-report scales was much higher at 39.3 %; 95 % CI 36.8–42.0 vs. by interview at 22.8 %; 95 % CI 18.6–27.6. In addition, point prevalence estimates of interview-based depression were also high in CKD stages 1–5 patients not treated with maintenance dialysis (21.4 %; 95 % CI 11.1–37.2), as well as in kidney transplant recipients (25.7 %; 95 % CI 12.8–44.9), but not as precise as those for patients with ESKD, as reflected in the wide confidence intervals. This could be due to a lesser number of studies evaluating the point prevalence of depression in early-stage CKD patients and transplant recipients.

2 Association of Depression with Adverse Clinical Outcomes

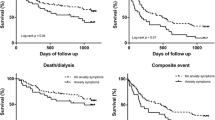

CKD or ESKD patients experiencing either depressive symptoms based on self-report scales or a clinical diagnosis of MDD are at a much higher risk of adverse clinical events as compared to similar patients without such symptoms or diagnosis (Box 23.2) [4–7]. These findings were not only reported in the kidney but also in the cardiovascular literature. The risk of death and hospitalization within a year doubles in ESKD patients on chronic dialysis with an interview-based clinical diagnosis of depression compared to those without it [4]. In addition, a clinical diagnosis of depression may increase cumulative hospital days and number of admissions to the hospital by 30 % independent of other comorbidities (Box 23.2) [2]. Furthermore, depression is an independent risk factor for recurrent cardiac events, rehospitalization, and death in many chronic diseases including CVD and CHF, similar to its independent association with the risk of hospitalization, progression of kidney disease, initiation of dialysis, and death in patients with CKD and ESKD (Box 23.2) [4–7]. Noticeably, the strength of association of depression with adverse outcomes is as high as some of the other comorbidities including diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, and congestive heart failure. Depression not only predicts adverse clinical outcomes, it decreases quality of life (QOL) and aggravates physical and sexual dysfunction in patients with CKD and ESKD substantially (Box 23.2) [8, 9]. It is, therefore, important to identify and manage levels of depression and functional impairment without which such problems fail to remit spontaneously in untreated CKD and ESKD patients.

Box 23.2. Clinicians Must Know That Depressive Symptoms and a Clinical Diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder in CKD and ESKD Patients Are Independently Associated with Adverse Clinical Outcomes

-

1.

Death

-

2.

Hospitalization (increased cumulative hospital days and number of admissions)

-

3.

Progression of kidney disease

-

4.

Initiation of dialysis

-

5.

Poor quality of life

-

6.

Physical and sexual dysfunction

3 Risk Factors for Depression in Patients with CKD

As depressive symptoms and MDD prognosticate poor clinical outcomes and decreased QOL in patients with CKD and ESKD, clinicians must be able to recognize the risk factors for depression (Box 23.3). Several risk factors for depression in this high-risk population are similar to those in the general population and include younger age, female gender, low household income, lower education level, and unemployment (Box 23.3) [2, 8–10]. Although white race has been reported as a risk factor, a high level of depressive affect has also been reported among urban African American ESKD patients treated with maintenance hemodialysis [6]. Dialysis-related factors such as nonadherence to diet and interdialytic weight gain are associated with depression, but it is not clear whether they are risk factors for or result from the presence of depression [2, 6, 8–10]. Other clinical conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypoalbuminemia, cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases, and comorbid psychiatric disorders, commonly associated with CKD and ESKD, add medical complexities and increase the risk for depression [2, 6, 8–10]. The association between medical comorbidities and depression is similar to the general population. Depression makes social interactions and relationships more difficult for patients, leading to estrangement from spouse, family, work, community, and religious organizations (Box 23.3) [8]. Post-dialysis fatigue, time spent on dialysis, cognitive impairment, and comorbid illnesses may be further impediments to social interactions and impair ability to build relationships. An attempt should be made by clinicians to identify interrelated risk factors for depression in order to best manage their patients with CKD or ESKD diagnosed with depression.

Box 23.3. Clinicians Must Be Able to Recognize the Risk Factors Associated with Depression in CKD and ESKD Patients

-

1.

General factors:

-

(a)

Younger age

-

(b)

White race

-

(c)

Female gender

-

(d)

Low household income

-

(e)

Lower education level

-

(f)

Unemployment

-

(a)

-

2.

Dialysis-related factors:

-

(a)

Nonadherence to recommended diet

-

(b)

Nonadherence to interdialytic weight gain

-

(a)

-

3.

Other comorbid illnesses/conditions:

-

(a)

Diabetes mellitus

-

(b)

Hypoalbuminemia

-

(c)

Cerebrovascular disease

-

(d)

Cardiovascular disease

-

(e)

Other psychiatric disorders

-

(a)

-

4.

Psychosocial factors:

-

(a)

Impaired social interactions

-

(b)

Estranged spouse

-

(c)

Estranged family members

-

(a)

4 Potential Mechanisms for the Association of Depression with Adverse Outcomes

It is unclear whether depression itself has a direct mechanistic role in the development of cardiac events and other adverse clinical outcomes or whether it is merely a surrogate marker of comorbid illness (Fig. 23.1). However, specific biological factors were proposed and investigated as potential mechanisms by which depression may lead to cardiac events that are compelling. First, both depression and CVD appear heritable in twin studies. In a study that included 2,700 male twin pairs from the Vietnam era, there was a correlation between genetic influences on depression and CVD, suggesting a common genetic link [2]. Second, depression leads to nonadherence with medications, unhealthy lifestyle, malnutrition, and loss of social network that can precipitate adverse events such as increase in peritonitis events noted in depressed chronic peritoneal dialysis patients compared to those who are not depressed [2]. Third, there are reports of altered autonomic tone, such as lower heart rate variability, in patients with recent MI with depression leading to coronary vasoconstriction and tachyarrhythmias. Therefore, autonomic dysfunction may be a potential pathophysiologic mechanism that can explain how depression leads to adverse clinical outcomes [2]. Fourth, several studies observed enhanced activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis, specifically increase in cortisol and norepinephrine secretion, in patients with CVD and depression. It is hypothesized that increase in the levels of inflammatory cytokines due to depression may result in hyperactive hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and increase in cortisol and norepinephrine secretions. It is further postulated that increase in cortisol and norepinephrine levels may be important in decreasing the availability of tryptophan, an important precursor for neurocellular function, and thus precipitate depressive symptoms by decreasing the availability of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin [2]. Fifth, inflammation has been implicated, such as an increase in serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and decrease in omega-3-fatty acid serum concentrations. There is an association between inflammation and depression as shown in some patients treated with interferon alpha who show a decrease in brain dopamine and serotonin levels that is treatable with paroxetine. To further support the role of inflammation, it was reported that depressed patients with psoriatic arthritis show improvement in their disease activity and depression when treated with etanercept [2]. Finally, the most compelling proposed mechanism of depression predicting adverse clinical outcomes is the association of altered serotonin levels seen in depression, with resultant increased platelet activation and vasoconstriction that can then lead to coronary events [2]. However, all of the above are potential mechanisms to explain how depression predicts poor outcomes. Future studies are needed to confirm the mechanistic pathways involved in adverse clinical outcomes in depressed patients with kidney disease, such as higher rates of cardiovascular events, progression to ESKD, death, and hospitalizations.

5 How to Identify Depression in Patients with CKD

Given one out of four or five patients with CKD or ESKD may be depressed, which puts them at increased risk for adverse clinical outcomes, poor QOL, and functional impairment, it is important for clinicians to screen such patients for depression. It(QIDS-SR16) are validated screening tools in CKD patients not yet initiated on maintenance dialysis (Table 23.1).

Compared to patients without kidney disease, those with ESKD requiring maintenance dialysis have higher cutoffs on the self-report rating scales to diagnose MDD, perhaps due to the presence of somatic symptoms associated with uremia or chronic disease. For example, the cutoffs on the 21-item BDI-II validated for the diagnosis of MDD in the general population, CKD and ESKD are ≥10, ≥11 and ≥14–16, respectively [12, 13]. The 20-item CES-D cutoffs in the general population and ESKD are ≥16 and ≥18, respectively. There is no difference in the PHQ-9 and QIDS-SR16 cutoffs between the general population and patients with kidney disease (Table 23.1).

Given the coexistence of somatic symptoms of depression in CKD patients with uremic symptoms and other comorbid medical conditions, those who screen positive on self-report scales need to be further assessed with a structured interview to confirm a clinical diagnosis of depressive disorder, such as MDD. In research, clinician-administered structured interviews such as the Structured Clinical Interview for Depression (SCID) or the Mini-international Neuropsychiatric Interview(MINI) have been used to establish diagnosis [12, 13]. These interviews take a significant amount of time (30–60 min) and require a certain level of training to administer. Therefore, in the clinical setting, eliciting the presence of 5 or greater of the depression symptom domains, including the presence of sadness or anhedonia, for a period of at least 2 weeks would confirm the presence of a clinical depressive disorder (Box 23.1).

6 Differential Diagnosis of Depression in Patients with CKD

Of the psychiatric illnesses identified among the US Medicare ESKD patients admitted to hospitals, the prevalences of depression, dementia, and substance or alcohol abuse could be found in as high as 26, 26, and 15 % of such patients, respectively [10, 14]. Therefore, it is important for providers to recognize the differential diagnosis of depression in an attempt to manage patients appropriately (Fig. 23.2) [11].

Importantly, there is a need to simultaneously identify cognitive impairment commonly seen in CKD and ESKD patients. Persistent and/or progressive impairment in memory and other cognitive functions such as attention, language, orientation, reasoning, or executive functioning, the cognitive skill necessary for planning and sequencing tasks, is defined as dementia [14]. A score of <24 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is commonly used to suggest dementia, which has limited sensitivity and specificity in patients with CKD and ESKD. The prevalence of dementia may be as high as 16–38 % in such patients. This too should be appropriately recognized by clinicians, as it also predicts poor outcomes. In addition, cognitive dysfunction acts as an impediment to decision-making, adhering to complex medicine dosing schedules, and self-care. Dementia is more insidious in onset, progressive in course over months to years, usually not reversible, and impairs consciousness in advanced stages. Interestingly, many of the risk factors associated with MDD are similar to those for dementia [14].

Delirium can masquerade dementia and depression and should be part of the differential [14]. Clinicians should recognize the fluctuating course of delirium that develops over a short period of time associated with lack of attention and consciousness. Usually, there is no complaint pertaining to loss of memory, and it occurs as a result of medical conditions (e.g., cardiac disease, liver disease, hypertensive encephalopathy, infections, hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, and hypercalcemia), side effects of certain medications (e.g., opioids, benzodiazepines, antihistamines, antipsychotics, and anticholinergics), or intoxications. Unlike dementia, delirium and depression are usually reversible. In addition, depression can be acute or insidious in onset and is associated with intact consciousness unlike delirium. Therefore, it is very important to differentiate dementia, delirium, and depression so that management can be tailored accordingly. Box 23.4 shows important differences in dementia, delirium, and depression. Proper workup to rule out other disorders includes (a) medication review; (b) obtaining laboratory data to rule out vitamin B12 and folate deficiency, thyroid dysfunction, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, and substance abuse; (c) obtaining brain imaging for presence of significant atherosclerotic cerebrovascular disease; (d) assessing sleep disorders (such as restless legs and obstructive sleep apnea) by history and physical examination; and (e) assessing dialysis adequacy, anemia, and aluminum toxicity in ESKD patients.

Box 23.4. Clinicians Must Be Able to Differentiate Delirium and Dementia from Depression [14]

-

1.

Delirium:

-

(a)

Develops over a short period of time

-

(b)

Lack of attention and consciousness

-

(c)

No complaints pertaining to loss of memory

-

(d)

Occurs as a result of:

-

(i)

Medical conditions

-

(ii)

Side effects of certain medications

-

(iii)

Intoxications

-

(i)

-

(e)

Reversible

-

(a)

-

2.

Dementia:

-

(a)

Develops over months to years, insidiously and progressively

-

(b)

Altered consciousness in advanced disease

-

(c)

Loss of memory common, along with loss of at least one other cognitive function such as:

-

(i)

Attention

-

(ii)

Language

-

(iii)

Orientation

-

(iv)

Reasoning

-

(v)

Executive functioning

-

(i)

-

(d)

Rarely reversible

-

(a)

-

3.

Depression:

-

(a)

Can develop acutely or insidiously

-

(b)

Not associated with altered conscious-ness

-

(c)

Complaints of memory loss can be present

-

(d)

Reversible

-

(a)

Apart from delirium and dementia, generalized anxiety is quiet common in patients with kidney disease and should be distinguished from depression by identifying patients who worry excessively on more days than not about a number of topics that has persisted for more than 6 months and with the self-perception that they are worried and lack control to modify its intensity and frequency [1]. This accompanies three of the six criterion symptom domains including fatigue, irritability, muscle tension, sleep disturbance, psychomotor agitation, and disturbed concentration [1]. Similarly, somatic symptoms such as sleep disturbances, sexual dysfunction, low energy level, easy fatigability, and weight and appetite changes can be present with uremia and make the diagnosis of MDD difficult. Alcohol and other substance abuse-related disorders should be excluded, as these are commonly associated with depression (Fig. 23.2).

7 Treatment of Depression in Patients with CKD

A diligent clinician should recognize MDD, identify its risk factors, triage patients at risk for suicide, and tailor management based on the needs of the specific patient and the resources available [11]. Screening tools enable clinicians to identify patients who are at risk for suicide. It is important to differentiate “thoughts for suicide” from “thinking about death” in patients with end-stage and terminal diseases such as ESKD and cancer in order to triage patients appropriately. Given that a majority of patients with kidney disease are elderly, “thoughts of death” may be common without depressive symptoms or thoughts of suicide. Furthermore, those who screen positive for suicidal thoughts should be queried for presence of suicidal intent or plan (Box 23.5). Those with suicidal intent or plan should be referred to an emergency room or urgent care facility that can provide further urgent psychiatric clinical assessment and triage and appropriate support groups.

Box 23.5. Clinicians Must Be Able to Recognize Those at Risk for Suicide So That Time-Dependent Interventions Can Be Implemented

-

1.

In those with thoughts of suicide or death, ask about suicidal intent or plans:

-

(a)

How often do you think about suicide?

-

(b)

Have you made any plans?

-

(c)

Have you tried taking your life before?

-

(d)

How do you plan to end your life?

-

(e)

What will prevent you from taking your life?

-

(a)

-

2.

Those patients who have suicidal intent should be immediately referred to an emergency room for further evaluation. Appropriate steps should be taken to organize support groups from family, friends, community, and religious and social organizations based on the availability of resources.

Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions can be implemented to treat MDD in CKD and ESKD patients [11]. Unfortunately, proposed interventions are not completely evidence-based due to a paucity of large enough studies and placebo-controlled randomized trials to establish the safety and efficacy of antidepressant medications and other interventions for the treatment of depression in CKD and ESKD patients [11]. Second, a high medication discontinuation rate is commonly observed in depressed patients with kidney disease [11]. Third, safety concerns of adverse events drive clinicians to either undertreat MDD or underdose antidepressants in CKD and ESKD patients (Box 23.6) [11]. Encouraging results of efficacy for the use of antidepressants in treating MDD associated with chronic diseases such as CVD come from a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial, the Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Trial (SADHART), which showed sertraline to be safe and efficacious in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Based on these results, sertraline may be considered for treating MDD in CKD and ESKD individuals [11]. Sertraline is being currently evaluated by the double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, flexible-dose Chronic Kidney Disease Antidepressant Sertraline Trial (CAST) (clinical trials identifier number, NCT00946998). Despite the paucity of data in patients with advanced CKD and ESKD, guidelines were developed by the European Renal Best Practice recommending the use of antidepressants in patients with CKD stages 3–5, which are summarized in Box 23.7 [15].

Box 23.6. Clinicians Face Day-to-Day Challenges in Treating Depression Because of Lack of Data Regarding Safety and Efficacy of Antidepressant Medication Use in Patients with CKD and ESKD

-

1.

Lack of large studies and placebo-controlled randomized antidepressant trials in CKD stage 3b-5 and ESKD

-

2.

High rate of medication discontinuation seen in small studies

-

3.

Safety concerns related to adverse events from antidepressant medications thought to be due to:

-

(a)

Renally excreted active metabolites and risk of accumulation to toxic levels

-

(b)

Risk of drug–drug interactions given the presence of other comorbid conditions and high pill burden

-

(c)

Cardiac side effects of several classes of antidepressants that may worsen the disproportionate burden of cardiovascular disease seen in CKD and ESKD patients

-

(d)

Increased risk of bleeding in the setting of uremic platelet dysfunction

-

(e)

Side effects of nausea and vomiting that may exacerbate uremic symptoms

-

(f)

CNS depression that may increase risks of cognitive dysfunction or delirium

-

(a)

Box 23.7. What the Guidelines Say You Should Do: Use of Antidepressants in CKD Stages 3–5 Patients [15]

-

1.

Active treatment should be started for patients with CKD stages 3–5 who meet the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder—level of evidence and recommendation: 2D.

-

2.

Treatment effect should be reevaluated after 8–12 weeks of treatment with antidepressant drug therapy—level of evidence and recommendation: 2D.

-

3.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors should be the first line of therapy if pharmacological intervention is considered for patients with CKD stages 3–5—level of evidence and recommendation: 2C.

Table 23.2 describes the potential side effect profiles of several classes of common antidepressants that can occur at increased frequency in CKD and ESKD patients compared to those with no kidney disease [11]. Although there is lack of significant data on the safety and efficacy for the use of antidepressant medicines in advanced CKD stages 3b-5 and ESKD patients, this should not discourage clinicians from treating depression appropriately until more data becomes available. Management strategies require discussion of risks vs. benefits of antidepressant medications with patients, the use of a class of antidepressant with the least possible drug–drug interactions, starting antidepressants at a lower dose than that recommended for patients without kidney disease, and close follow-up to monitor treatment response, side effects, and need for dose adjustment. Providers should pay special attention to drug–drug interactions that are highly likely in chronic hemodialysis patients due to polypharmacy. Typically, antidepressants should be started at low doses and dose escalation should be based on response and tolerability after at least 1–2 weeks of treatment on a particular dose.

Non-pharmacological interventions hold promise for the management of MDD in CKD and ESKD patients without increasing pill burden or raising concerns regarding adverse events and drug–drug interactions [11]. Such interventions include changes in dialysis prescription, exercise, and cognitive behavioral therapies that were shown to be efficacious in the general population (Box 23.8). The Following Rehabilitation, Economics and Everyday-Dialysis Outcome Measurements(FREEDOM) cohort observational study reported improvements in the depressive symptom severity scores measured by the BDI-II scale and health-related QOL measured by the Short Form-36 (SF-36) with six times weekly hemodialysis [11]. However, although in the Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) trial, frequent hemodialysis (six times a week as compared with three times a week) was associated with significant benefits with respect to both co-primary composite outcomes of death or increase in left ventricular mass and death or a decrease in the physical-health composite score, there were no significant effects of frequent hemodialysis on cognitive performance or self-reported depression [16].

Box 23.8. Clinicians Should Be Aware of the Non-pharmacological Interventions That Can Be Used to Treat Major Depressive Disorders in Patients with CKD and ESKD

-

1.

Alterations in dialysis prescription

-

(a)

Frequent dialysis, six times vs. three times per week

-

(a)

-

2.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

-

(a)

Trained psychologist to administer therapy

-

(b)

Trained social worker to administer support and therapy

-

(a)

-

3.

Exercise training therapy

-

(a)

Resistance training exercises (e.g., ankle weights)

-

(b)

Aerobic exercises

-

(a)

-

4.

Treatment for anxiety, pain, sleep disorders, and sexual dysfunction

-

5.

Alternative approaches:

-

(a)

Music and art therapy

-

(b)

Involving community and religious organizations

-

(c)

Social interventions to gain support from family and friends

-

(a)

Weekly cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) by a trained professional for 12 weeks or more was reported to improve depressive symptom severity on the BDI-II scale and overall QOL on the Kidney Disease QOL Questionnaire-Short Form (KDQOL-SF). A trained psychologist attempts to restructure negative thoughts and encourage logical thinking so as to modify behavior and mood. Those who ineffectively handle problems and/or make poor decisions are able to better cope with adversities and improve their depressive symptom severity [11]. This technique administered by trained social workers to the ESKD patients after Hurricane Katrina showed encouraging results in assuaging depressive symptoms. Combined pharmacological intervention and CBT may be also considered, as used in the general population, based on the availability of resources [11]. Decreased functional capacity is common in patients with ESKD and is associated with poor QOL measures. Resistance exercise training by ankle weights was reported to improve QOL in patients on chronic maintenance hemodialysis. Similarly, aerobic exercise over 10 months was effective in improving heart rate variability, depressive symptom severity and QOL measures in a small group of chronic hemodialysis patients. Therefore, exercise training can potentially function as a non-pharmacological intervention that clinicians can prescribe to treat MDD in CKD and ESKD patients.

Other potential approaches to treat MDD in CKD and ESKD patients focus on pain management, improving sexual function, and management of anxiety (Box 23.8) [11]. Future research is required to evaluate if community and religious organizations may intervene and ameliorate depressive symptoms of CKD and ESKD patients by improving their social interaction skills. This may also help in addressing and overcoming marital and family discord that is commonly found in this patient population. Music and art therapy is an exciting field that remains to be more fully explored in patients on chronic hemodialysis while they remain idle on the dialysis machine for a long period of time. It remains to be investigated whether treatment of depression in patients with CKD can result in improvements in QOL and survival (Fig. 23.3) [11].

8 Recommendations and Conclusions

Depression is common in patients with kidney disease but less frequently recognized and inadequately treated. It is well established that a diagnosis of current MDD or depressive symptoms independently predicts adverse clinical outcomes in patients with kidney disease. Therefore, it becomes imperative for clinicians who are involved in the care of such patients to screen for and diagnose depression accurately. Several quick and easily administered self-report scales are validated to screen for depression in these patients. However, those who screen positive for depression on screening need to be further evaluated so that dementia, delirium, anxiety disorders, medication side effects, and other medical conditions that may lead to the presence of somatic symptoms, such as underlying sleep disorders, thyroid dysfunction, or dialysis inadequacy, can be excluded. Finally, appropriate management strategies should be implemented to maximize efficacy and safety of depression treatment using available pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions that are acceptable to specific patients. The ultimate goal of a clinician should be to assuage depressive symptoms and potentially achieve complete remission of depression.

Before You Finish: Practice Pearls for the Clinician

-

Clinicians should be able to recognize the risk factors for depression.

-

Clinicians should understand the differences between depressive symptoms and a clinical diagnosis of major depressive disorder.

-

Screening for depression should be performed at the first outpatient evaluation in the chronic kidney disease or dialysis clinic and then repeated annually.

-

Validated self-report tools exist that can be easily administered to screen for depression. Subsequently, a current major depressive disorder should be confirmed by a clinician interview in those who screen positive.

-

Those at risk for suicide should be identified for urgent triage and further management.

-

A broad differential diagnosis should be considered, based on appropriate physical examination, Mini-Mental State Examination and laboratory data.

-

Once a diagnosis of major depressive disorder is confirmed, a thorough review of risks vs. benefits of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions should be discussed with patients to tailor individualized management strategies.

-

To start an antidepressant medication, the lowest possible dose should be initially prescribed, followed by frequent monitoring and gradual dose escalation every 1–2 weeks based on patient’s response to and tolerability of the medication.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Hedayati SS, Finkelstein FO. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of depression in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:741–52.

Palmer S, Vecchio M, Craig JC, Tonelli M, Johnson DW, Nicolucci A, et al. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int. 2013;84:179–91.

Hedayati SS, Bosworth H, Briley L, et al. Death or hospitalization of patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney Int. 2008;74:930–6.

Lopes AA, Bragg J, Young E, Goodkin D, Mapes D, Combe C, et al. Depression as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization among hemodialysis patients in the United States and Europe. Kidney Int. 2002;62:199–207.

Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, Simmens SJ, Alleyne S, Cruz I, et al. Multiple measurements of depression predict mortality in a longitudinal study of chronic hemodialysis outpatients. Kidney Int. 2000;57:2093–8.

Hedayati SS, Minhajuddin AT, Afshar M, Toto RD, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ. Association between major depressive episodes in patients with chronic kidney disease and initiation of dialysis, hospitalization, or death. JAMA. 2010;303:1946–53.

Cohen SD, Norris L, Acquaviva K, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL. Screening, diagnosis, and treatment of depression in patients with end-stage renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:1332–42.

Cohen SD, Patel SS, Khetpal P, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL. Pain, sleep disturbance, and quality of life in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:919–25.

Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, Simmens SJ, Boyle DH, Umana WO, et al. Psychologic functioning, quality of life, and behavioral compliance in patients beginning hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:2152–9.

Hedayati SS, Yalamanchili V, Finkelstein FO. A practical approach to the treatment of depression in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2012;81(3):247–55.

Hedayati SS, Minhajuddin AT, Toto RD, Morris DW, Rush AJ. Validation of depression screening scales in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:433–9.

Watnick S, Wang PL, Demadura T, Ganzini L. Validation of 2 depression screening tools in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:919–24.

Kurella Tamura M, Yaffe K. Dementia and cognitive impairment in ESRD: diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Kidney Int. 2011;79:14–22.

Nagler EV, Webster AC, Vanholder R, Zoccali C. Antidepressants for depression in stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety with recommendations by European Renal Best Practice (ERBP). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(10):3736–45.

The FHN Trial Group. In-Center hemodialysis six times per week versus three times per week. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2287–300.

Acknowledgments

Work from Dr. Hedayati’s laboratory was supported by grant number R01DK085512 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and VA MERIT grant (CX000217-01). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDDK, the National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jain, N., Hedayati, S.S. (2014). Depression and Other Psychological Issues in Chronic Kidney Disease. In: Arici, M. (eds) Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-54637-2_23

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-54637-2_23

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-54636-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-54637-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)