Abstract

When talking about Lenovo, people normally think of Liu Chuanzhi. Lenovo’s development could not have been achieved without Liu Chuanzhi’s acute judgment in dealing with various situations, excellent social skills and farsighted views.

This paper is sponsored by the Distinguished Young Scholar Fund, National Natural Science Foundation (70925002) “organizational behaviors and corporate culture”

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Corporate Culture

- Chinese Enterprise

- British Telecom

- Subsidiary Company

- Original Equipment Manufacturing

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

When talking about Lenovo, people normally think of Liu Chuanzhi. Lenovo’s development could not have been achieved without Liu Chuanzhi’s acute judgment in dealing with various situations, excellent social skills and farsighted views.

In 1984, Lenovo started its business journey in a small flat. Liu Chuanzhi likes to use incubation as a metaphor to describe the development of Lenovo. It was a tough incubation in an environment of unsuitable temperature; but the company also grew strong and resilient in trying to survive in this environment. Liu Chuanzhi successfully negotiated all the ‘business risks’ and ‘policy risks’, and overcame many thrilling challenges.

While walking on the ice, Liu Chuanzhi didn’t forget to seize the opportunities and he made Lenovo a stunningly brilliant performer on China’s business stage. During the middle 1990s, he spent nearly 7 years accomplishing the conversion of the property rights of Lenovo, a state-owned enterprise. He supported Lenovo’s strategy of raising the “big flag of China’s own brand”, which successfully won over the government’s support and favorable policies, and took Lenovo’s computers to top of the business in China’s market.

Besides adapting to and coordinating patiently with the macro environment, Liu Chuanzhi also led Lenovo to practice “internal strength”, which was to promote the standardization and institutionalization of management. Lenovo completed its first batch of rules and regulations in 1990. Thousands of clauses were written based on the “big boat structure”. It put the company on an institutionalized track from the aspects of politics, economics, organizational structure, legal issues and systems etc. Meanwhile, through many means, Liu Chuanzhi highlighted ‘unification’ in Lenovo’s culture. Through a “human mold” plan, he had employees deeply absorb the enterprise’s management mode.

During the 20 years Lenovo has developed, Liu Chuanzhi deems the hardest part is when new employees replace old employees, especially the fostering of successors. He launched a “new talents strategy”. He first had Guo Wei take over some of the tough business areas, and then appointed Yang Yuanqing to take over the PC department. The great performance of Yang Yuanqing became the turning point for Lenovo PC and China’s PC industry. Liu Chuanzhi then made up his mind that Yang Yuanqing would be his successor. However, he discovered that, as a young person, Yang Yuanqing always took things too seriously and lacked flexibility. So he taught Yang Yuanqing a lesson on how to ‘compromise’, and finally groomed him to become the perfect successor.

Lenovo frequently made big moves as it stepped into the twenty-first century. From “Legend” to “Lenovo”, becoming the biggest sponsor of the Olympics, and buying IBM’s PC business – like a snake swallowing an elephant – a “new Lenovo” was striding forward into “international enterprises”. After Lenovo purchased IBM PC, Liu Chuanzhi resigned as the group’s chairman of the board. In 2009, however, with Lenovo’s business under serious pressure from the global economic crisis, Liu Chuanzhi, who was already 65 years old, returned to this post. He spent several months reorganizing the global structure, worked tirelessly to retrieve the losses, and made significant improvement.

When looking back on his career, Liu Chuanzhi said: “When I first wanted to establish Lenovo, the main reason was to represent the value of my life. But now the goal I’m working on is to make Lenovo a great company. What is a great company? The first thing is to last long. Companies that die in a year are not good companies, no matter how good they used to be. The second thing is to be large-scale. It has to be significantly influential. Thirdly, it contributes to social and the country’s development progress in terms of science, enterprise management, and even culture. Another desire is to let young people do this. They are shareholders themselves. They are also managers and operators.”

From 1953 to 1978, the average annual growth of China’s GDP was 6.1 %. However, in the 30 years since China’s reform and opening-up in 1978, the annual GDP growth was 9.8 %. When China started to transform from a planned economy to a market economy, many people started to build up enterprises. They drove the enterprises to continually develop, and accordingly pushed forward the fast development of China’s economy.

The entrepreneurs we are talking about in this chapter refer to those top leaders of enterprises who set running the enterprises as their missions and goals. They acutely perceived the opportunities in the market, mobilized existing resources, built up enterprises and working teams, and obtained profits from providing products or services. Since the market of professional managers in China is still not very mature, and the trusteeship for enterprises still needs to be improved, these people may also play the role of top managers in enterprises. In this chapter, entrepreneurs and top leaders of enterprises are considered the same.

Compared with Western entrepreneurs, Chinese entrepreneurs have a few unique features. Firstly, most of China’s entrepreneurs have started their businesses since the 1980s. They were the founders of the enterprises. They also played the roles of leaders and managers or other roles. For many of the West’s entrepreneurs, when they took over their enterprises, even though they also played the role of leaders when encountering change, they were more like senior professional managers. Secondly, Chinese entrepreneurs experienced a dramatic change in the social environment. There were many grey areas in the country when transforming from a planned economy to a market economy and these contained rich opportunities but also had many hidden risks. Leading enterprises out of the chaos needed experience, capacity, and most importantly, political wisdom. In contrast, most of the challenges faced by Western enterprise leaders stemmed from competition in the market. Comparatively, policy and systems didn’t bring them much trouble. Finally, after China’s market economy was established, Chinese entrepreneurs led their enterprises to improve capacities during market competition, and some of them stepped on to the international stage. In competing with big enterprises from developed countries on the same market, Chinese entrepreneurs lacked the huge capacities and corporate brands of their international competitors. Western entrepreneurs even had the advantage of intangible assets relating to their countries’ culture. In the international business arena, Chinese entrepreneurs were the late comers. Western enterprise leaders had abundant capital and established brands; they were the front runners of the international proscenium.

In this chapter, we will firstly introduce the features of the environment in which Chinese entrepreneurs grew up, then we will introduce the characteristics of the entrepreneurs who emerged from three different time periods, and finally we will make a simple conclusion on the common characteristics of Chinese entrepreneurs.

4.1 The Environment for the Growth of Chinese Entrepreneurs

I always think that Chinese enterprises and entrepreneurs have been through a lot more torturing than others during the last 20 years. These 20 years were a period of radical change; it made many enterprises precocious, and also caused many to die. The living environment for Chinese enterprises in these 20 years has been changing along with the reform of the country’s political and economic systems. Enterprises, as participators, also promoted the change of the macro environment through their efforts and adjustments. They also have been changing and evolving themselves. All these experiences are unforgettable in the heart.

Ning Gaoning

Just as what we discussed in Chap. 3, China’s policy of economic reform and the change in the macro environment provided soil in which entrepreneurs could grow. Without the reform of macroeconomic policies, there wouldn’t be these many entrepreneurs and these dynamic enterprises. Under the same environment, how did some enterprises succeed, while others, which were in the same industry and had the same ownership structure, fail? Apparently, the role of entrepreneurs is essential. During China’s economic system reform process, the problems faced by entrepreneurs were non-structured. There were no previous examples to reference; thus, entrepreneurs’ judgments and their abilities to adapt were among the major determinants for their enterprises’ success or failure. The enterprises’ operational practices that we are going to explore in this chapter basically reflect the perceptions and conceptions of their top leaders.

An enterprise’s leader needs to be acutely aware of the changes in the external environment and formulate proper strategies accordingly, while also coordinating internal elements to ensure the implementation of enterprise’s strategies and performance objectives. To Chinese enterprises’ leaders, dealing with changes in the external environment is more important than integrating internal resources. This is the key argument of this chapter. The policy-related risk caused by uncertain institutions has been the biggest risk faced by Chinese entrepreneurs during the transitional period. Leaders have to take effort to diminish or even eliminate the harm caused by the uncertainty through proper behaviors and correct decisions.

At the beginning of the economic reform, Chinese entrepreneurs were facing a sort of “mixed economic environment” or a “transforming economic environment”. The whole society was in the transition from a planned economy to a market economy, from an autocratic society to a legal society. Many rules and regulations were not established at the beginning. Many policies and regulations, which were closely related to the business operation of enterprises, were gradually formed in the way of “touching the stones to cross a river”. Too many controls from governments; too much flexibility in executing laws and regulations; many people not playing by the rules in commercial competition; and the whole society not appreciating credit, unlike in a mature commercial society; all these factors increased the instability and uncertainty of Chinese enterprises in the transitional period (Guthrie 1997). For example, in the face of difficulties caused by sudden changes in policies, Pan Shiyi used to express his frustration, saying: “I feel like we are in the middle of a football game, the judge suddenly blows his whistle and says that we are now changing into a volleyball game, the ball cannot touch the ground, otherwise it will be judged a foul.”

Shi Yuzhu listed the external factors which caused the death of some private enterprises: there were disordered commercial cultures and credits, and twisted social public opinion, there were also the random punishments and fines placed on enterprises by authorities, and obstacles created by government officials by using their power etc. He believed that there was too much flexibility in the legal system, which provided large spaces for law executors to explain their behaviors. “There are things, which are good things if you say it in this way, but may become illegal things if you say it in another way. In addition, there was the unreasonable legal system, which forced you to get out of line. For example, the rules required that importing computers must have a license, but it was impossible for private enterprises to get licenses. If you wanted to be in the computer business, you had to buy a license. According to some rules, buying a license was illegal. You either do nothing or do something illegal. There are similar cases in other businesses.”

Due to the ambiguity and changes of policies in the transitional period, the priority task for entrepreneurs was not thinking about strategic positioning, neither was it the development of new products nor innovation of services, but to understand and adapt to the complicated commercial environment, especially to deal with troubles caused by the insufficiency of institutions and changes of systems. At the beginning of the transition, because many policies developed in the planned economy were not suitable for the operation of enterprises, central and regional governments were all “touching the stones to cross a river”, with no new clear rules created. Powers were all centralized in the hands of government officials, so they had a lot of power to justify their decisions on whether the business of an enterprise was in line with the policies or in conflict with the policies. In circumstances where there was “no law to follow”, entrepreneurs needed to create a good external environment for their own development by employing skillful and practical strategies. They especially needed to strategically obtain the understanding and recognition of government officials. “The social connection is productivity” was the mantra that represented the importance of entrepreneurs being active in gaining the recognition of policy makers and especially policy executors. Academic research also shows that, before the mid-1990s, Chinese enterprises commonly used the strategy of using social networks. The more social networks managers had, the better performance enterprises had (Peng and Luo 2000). Because private enterprises were in a disadvantaged position compared to state-owned and collective enterprises, their high-level managers paid even more attention to social networks (Xin and Pearce 1996).

Many successful entrepreneurs patiently adapted to policies and the requirements of government agencies first, while using excellent performance to reward local governments and to influence their policy formulation. They even won rights to make their own decisions and played their influence through participating in policy making. In China, the institutional structure and incentive system or other macroeconomic policies stimulated the development of enterprises; enterprises in turn promoted the improvement of macroeconomic policies issued by governments, and formulated more policies to support the development of enterprises, as happened in the formulation of the Property Law and the Contract Law. Many private entrepreneurs started to influence governments’ policy formulation after they achieved success. For example, private entrepreneurs proposed the inclusion of the protection of private property in the constitution in the National People’s Congress and the National Political Consultative Conference. Therefore, the theme which runs through the journey of China’s Reform and Opening-up is that central and regional governments used unique ways to coordinate economic activities, which made enterprises and governments interact with each other. Both sides were the drivers and the receivers of system reform, and both sides commonly promoted the development of China’s economy (Krug and Hendrischke 2008).

The interaction between entrepreneurs and governments can be demonstrated from the following case. An entrepreneur was the leader of a state-owned enterprise in Nanjing that was involved in the system integration business in the mid-1990s. When it initiate the business, the local government invested 20 million Yuan. Over 2 years, he increased sales revenue to 360 million Yuan. In the face of increasingly fierce competition in the market, he realized that the government control limited the autonomy of the enterprise, which would compromise the enterprise advantages in competition with foreign companies and private companies. He lobbied the government officials with the idea that, if run along the lines of a private business, the enterprise could face the market and clients more flexibly. Due to his outstanding performance, the government accepted his idea and asked him to submit a formal proposal. He proposed to return the government’s original 20 million Yuan investment by 2.2 times. The government saw that this return matched the amount the state property had increased in value, so the proposal was accepted and the government quitted its equity and the enterprise became a purely private company. This company later received commitments totaling 15 million US dollars from the Intel Company of the United States and the Soft Bank Company of Japan to establish a corporation. However, according to a policy issued by Chinese government in 1986, joint ventures between foreign companies and private companies could not be registered. This entrepreneur submitted his proposal to officials in charge of each level, stating his case, and finally, the proposal was delivered to the National Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation Department, and was ultimately approved. This company became the first private company to be incorporated with foreign companies. From then on, the Chinese government revised its policies on co-investment of Chinese and foreign companies.

During the past 30 years, the external environment faced by Chinese entrepreneurs has changed a lot. Different time periods have created different types of entrepreneurs. From the perspective of the macroeconomic environment, the development of Chinese enterprises can be divided into three phases. The first phase was from the early 1980s to late 1990s, when the country’s economic system was in the process of transition, and under the major policy of invigorating the economy. There were no clear and detailed policies from the government to follow, opportunities and risks co-existed for businessmen. Many people were enticed by the opportunities and took the risks; some of them were punished for overstepping the red line of policies, some of them were destroyed by going against the commercial law and over expanding. Only those people who cautiously interpreted the policies, and had strong will, superior patience and motivation, could finally lead their enterprises successfully through the transitional period.

The second phase started in late 1990s. China had accumulated more and more experience during the progressive market reform. The institutional environment was also significantly improved, and entrepreneurs not only had more autonomy to run businesses and improve management, but also could get different kinds of reasonable rewards and incentives. The improvement of the business environment meant that entrepreneurs no longer needed to deal with the chaos caused by the changing external environments, but could focus more on their business and management. However, since there were many foreign companies entering the market in different industries, enterprises were facing more severe competition, and leaders needed to use professional operation and management methods to enhance the competitiveness of their enterprises. Those enterprises that depended only on access to resources or took advantage of the loopholes in policies gradually disappeared under the market competition. And those enterprises that had developed by their own capacities became the outstanding ones in the market.

The third phase started at the beginning of the twenty-first century, when China joined the WTO, and the market economy was developing in depth and range. After experiencing the preliminary stage of the Reform and Opening-up, the overall economic power of China was tremendously enhanced. The purchasing capacity of consumers was increased and the consumption habit was also changed; the goods and products on the market were very rich; and Chinese and foreign companies were competing on an open market. In these circumstances, some enterprises that had forged their core capacities and leading edge on the Chinese market started to approach the international market. Among them, some fell down right after they stepped out of the door, but some extended their success.

“Times produce their heroes” – against this background, entrepreneurs who emerged from the different time periods can be categorized as the political wisdom type, professional specialty type and international operation type. The following three sections, based on the social environment and major tasks faced by entrepreneurs, will discuss the main characteristics of entrepreneurs from the three different time periods, disclose the three types of “heroes” forged by three different “times”, and figure out the growth paths and changing directions of Chinese entrepreneurs.

4.2 The Political Wisdom Type: Walking Out of the Chaos, Improving Management

During the past 20 years, our country had been struggling with the conflicts between the old and the new while going forward. If you surrendered yourself to the old system, you would be buried underneath it; if you stood against it, you could be destroyed. The distinctive part of Lenovo is that it found the way to get along with the old system. Meanwhile, it skillfully dealt with the disgusting defects of the old system by its amazingly strong willpower and patience, it got rid of the control bit by bit and headed for the new world.

Ling Zhijun

Since the Reform and Opening-up, there have been many excellent successful entrepreneurs, such as Liu Chuanzhi, Zhang Ruimin, and Ren Zhengfei. There are also some people who were successful for a short while, but were eventually thrown into jail, such as Yu Zuomin, Mou Qizhong, Huang Hongsheng, Shen Taifu, Hu Zhibiao, Zheng Junhuai, Zhang Rongkun, Zhou Zhengyi, Gu Chujun, and Huang Guangyu. Some of these people ignored the policies and laws of the country, and deliberately broke the rules for personal gain. Others attempted to look for acceptable ways to do business in the changing environment, but made mistakes and were punished. The government tightly controlled economic activities through law making, policy issuance, macroeconomic control and many other ways. Policies changed fast; some entrepreneurs were judged as breaking the law even before they has time to adapt themselves to the law.

The different methods enterprise leaders use to cope with policy environments may lead them along different paths. Some people act very straightforwardly, and put too much emphasis on their individual benefits; while some people communicate with government officials patiently and to obtain their understanding and support. The first way is too tough. Once there is malpractice, the enterprise will be held responsible. By comparison, being skillful and tactful is better for creating a good political environment for enterprises. However, many people gradually developed a kind of “official-like-business” mindset during the building of close relationships with officials who were in charge of policy making and enforcement. They used government’s support or took advantage of the loopholes in policies to gain profit. This type of business leader will eventually be washed out by customers and the market due to a lack of core competitiveness.

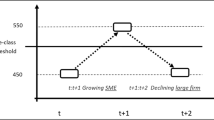

Compared with other types of entrepreneurs, the characteristics of the political wisdom type of enterprise leader are the most distinctive. We can divide entrepreneurs into four categories, based on their ways of adapting to environments, and internal management (see Fig. 4.1) (Zhang 2009). The first type is outside square, inside square. This type of entrepreneurs acts steadily and confidently when coming to inside management, but they can easily fall to policy risks because they are unable to adapt to the environment quickly and tactfully. Often, this type can not achieve their business goals during the transitional period. They are called “martyrs”. The second type is outside round, inside round. This type of entrepreneurs normally has very good relationships with governments, but they depend on policies and the support of government officials too much, and their enterprises lack organizational capabilities. As a result, they are eventually washed out by the market. They are called the “mediocre” type. The third type is outside square, inside round. This type of entrepreneur is very self-willed. They cannot fit in the policy environment; they look to be omnipotent inside the enterprises, but lack effective management and operation skills, which results in their enterprises only being a flash in the pan in the market. They are called the “Big King” type. The fourth type is outside round, inside square. They on the one hand wisely understand and adapt to the policies and institutional environments; on the other hand, they run their business with high standards, and make efforts to build the core competitiveness inside their enterprises to fit the market. They don’t solely rely on their relationships with the government or officials, neither do they go their own way without any basis in theory or experience. This type of entrepreneurs constantly improves their firms’ competitiveness, and is always vigorous in domestic and international markets. The success of this type of entrepreneur also provides good experiences for government officials to formulate more reasonable policies. This type of entrepreneurs belongs to an adaptive type. They are wise people who clearly understand the reality, and they are able to achieve success one way or another in the cracks of systems. They are called the political wisdom type of entrepreneurs.

The political wisdom type of entrepreneurs led enterprises out of the “fog” and “chaos” during the transitional period. Below is their four main characteristics.

4.2.1 Skillfully Dealing with the External Relationships

Even though maintaining good external relationships is necessary for all enterprises, it was especially crucial for enterprises during the transitional period. Policies and laws were uncompleted, commercial ethics and culture were not yet established, and there were few professional managers and employees with quality backgrounds. In these circumstances, running a business must have been extremely difficult. Once a problem occurred, it was impossible to follow criteria to make a judgment. It was even impossible to find a clear way to solve the problem. Entrepreneurs needed to have extreme patience and strong will to skillfully deal with all stakeholders, balance advantages and disadvantages, and find a safe solution. The president of Youngor Group, Li Rucheng, described his principles as “cave in when you meet something stronger”, sacrifice small interests to keep good relationships with the government, and engage in no hard battles with the reality. Shi Yuzhu’s principle is “ to figure out the rules, to create rules”, “to downplay yourself, to praise others” when dealing with big shots. The founder of China Pacific Construction Group, Yan Jiehe, used to say: “Clear compromise is noble, sincere compromise is what a hero does; how do you get harmony if there is no compromise?”

The president of automobile manufacturer Geely Group, Li Shufu, started producing refrigerator parts in 1986. In 1989, the country enforced a designation system for refrigerator manufacturing, and Geely was not on the list. As a result, Li Shufu had to close down the refrigerator factory. After giving up the refrigerator business, Li Shufu started in the automobile manufacturing business. However, in 2001, the State Economic and Trade Commission issued the “Notification of automobile manufacturing enterprises and products”, which excluded Geely. Li Shufu used to say: “There is a progressive process for the state’s policies on industry opening, some ‘red lights’ are just temporary. If the business is heading in the same direction as the country’s development, then we should be persistent, no matter how many difficulties there are. A ‘red light’ cannot be changed by force, but we can go across it or wait for the right time.” He constantly communicated with relevant authorities, and finally obtained permission to independently develop cars. He led his group to conquer many difficulties, and never gave up. Since entering the car industry in 1997, constant independent innovations have helped Geely develop very quickly. Now it has the capacity to produce 400,000 finished automobiles, 400,000 engines and 400,000 transmissions per year, and has total intellectual property covering eight series, including 30 finished automobile products. Geely has remained in the top 500 Chinese enterprises for 7 years and in the top 10 Chinese automobile enterprises for 5 years. It became the “base enterprise for the national finished automobile exportation”, and was honored as the enterprise which “developed the fastest and grew the most during the 50 years of China’s automobile industry”. In 2009, when the world was still in financial crisis, Geely achieved sales of 330,000 finished automobiles for the year, which was an increase of 48 % on the previous year. It also achieved sales revenue of 16.5 billion Yuan, up 28 % on the previous year; and nearly 2.4 billion Yuan in profits and taxes, a rise of 35 % on the previous year. On March 28, 2010, the Geely Group signed a final agreement with Ford Automobile Company to purchase 100 % of the shares and related property of Volvo Car Company for 1.8 billion US dollars. Li Shufu became the Economic Achiever of the Year and the Most Influential Businessman of Zhejiang Province for 2009 due to his outstanding courage and his strategy of indigenous branding.

In 1987, when Lenovo’s Han card, which allowed the input of Chinese characters into computers, was very popular in the market, officials in the pricing bureau deemed the price of the Han card was too high and contravened price regulations. They fined Lenovo 1 million Yuan. That year, the company’s after-tax profit was only 700,000 Yuan. Staff of the company were all very angry about this and wanted to hold a media conference to gain support from the media. Liu Chuanzhi decisively rejected this idea. He knew only by caving in to the price bureau first, could he win himself some space to work on a solution. He invited the chief of the price bureau for dinner, and finally the fine was reduced to only 400,000 Yuan. Liu Chuanzhi warned his staff: when doing things, “you need to know who you are”.

4.2.2 Properly Seeking the Support from Governments

China’s market economy was going forward while experimenting. Even though the country’s top leaders were wisely and farsightedly guiding the establishment of the socialist market economy, the conceptions and consciousness of many policy makers, officials in charge, law executors, and even many citizens were still stuck in the planned economy time. In this special period of time, entrepreneurs were facing a difficult situation: caving in to the old system meant doing nothing, purely waiting for the environment to change meant losing opportunities; but taking risks when the opportunities were not entirely mature might cause failure and bad consequences.

For example, an enterprise’s ownership reform involves the basic interests of the management level and all employees, as well as the important issue of to whom the enterprise belongs, which is crucial to the long-term development of the enterprise. However, there are no clear relevant policies; there are opportunities which can be taken advantage of, and there are also many traps and risks. Some people were too afraid to move due to the constraints from policies, some people had goals to reform but failed in the half way, and some other people ended up in jail because their bold movements infringed certain policies.

The reform of Lenovo can be considered as a typical successful case. When Lenovo became a listed company in Hong Kong in 1994, it was still a state-owned enterprise. Liu Chuanzhi wanted to find a legitimate way to ensure both the state’s interest and reasonable incomes for the enterprise founders and employees. He wanted to distribute 55 % of Lenovo’s property to the state and 45 % to the employees. However, according to the law, Lenovo could not be transformed from a state-owned enterprise to a state and public shareholders common-owned enterprise because Lenovo’s assets did not belong to its employees. However, policies existed that entitled Lenovo’s shareholder, the Chinese Academy of Science, the right to distribute the profits of the enterprise. The Chinese Academy of Science reserved 65 % of the profits to itself, and let Lenovo distribute the remaining 35 %, though the Academy didn’t really have the right to authorize Lenovo to change its right of distributing profits into distributing shares. After many years of communication, the Ministry of Finance finally agreed to allow Lenovo to buy 35 % of its state-owned shares, but requested Lenovo’s employees use cash to make the purchases. Liu Chuanzhi used the capital previously accumulated through the right of distributing 35 % of the profits to purchase this 35 % state-owned stake. So, through persistence and patience, the employees of Lenovo finally became the owners of the enterprise.

Liu Chuanzhi managed to understand the policies correctly and skillfully walked along the edges of the policies to break through the constraints of the old system while capturing the opportunities of the new system. By contrast, the reforms by Li Jingwei, the founder of Guangdong Jianlibao Group, had unfortunate results. Li Jingwei started Jianlibao’s business in 1984, and became famous to the world by sponsoring Chinese athletes at the 23rd Olympic Games. In the following 18 years, his successful marketing made Jianlibao the most popular beverage, with the best sales record in China. The company contributed profits and taxes to Sanshui city totaling 2.8 billion Yuan, and it used to account for 45 % of the local financial income. And Li himself was rewarded, receiving the national “May 1st” Labor Medal, being named a national model worker, and becoming a member of the 9th National People’s Congress.

At the establishment of Jianlibao, Sanshui city government held 75 % of the shares. In 1998, Li Jingwei decided to take Jianlibao into the Hong Kong market, but, unfortunately, the plan failed. Sales revenue constantly fell and the Group’s contributions to local finances hit a record low of 7 %. In order to stimulate the enterprise, the company’s management and the city government again began discussing reform in 2000. Under an initial proposal, most of the shares would be sold to Li Jingwei and the management level, providing they could raise their own funds to pay for the shares. The city government opposed this reform plan and started a share transfer plan, which was to sell 45 % of the shares for 380 million Yuan to a Singaporean company, but this plan was stopped by Li Jingwei’s opposition. Li Jingwei then proposed to buy Jianlibao’s shares for 450 million Yuan in installments over 3 years, but this plan was also rejected by the government officials. Later, Sanshui city government sold 80 % of the shares for 380 million Yuan to Zhejiang International Trust Limited. Half a year later, the anti-corruption department of Sanshui city government detained and interrogated Li Jingwei and three other general managers on suspicion of “being involved in removing a large amount of Jianlibao’s capital”. Some of those detained were later invited back to work at Jianlibao by different ways. Nevertheless, on Sept. 3, 2009, the intermediate court of Foshan city heard the embezzlement case against Li Jingwei and four other high-level managers of Jianlibao. Three managers were already not very well, and received 14–18 years’ jail each. Li Jingwei could not make it to the court because of illness. He applied for a postponement to his case, and received the acceptance of the court.

Li Jingwei’s battles with the government made his and Jianlibao’s unfortunate results inevitable. Government officials deemed they had given Li Jingwei the rights to manage the finances, personnel and decision-making of the enterprise, but it never occurred to Li Jingwei to report the business’s operations back to the government. In their eyes, Li Jingwei never really thought the government was worth respect. However, from Li Jingwei’s perspective, Sanshui government had been the biggest shareholder of the company from the establishment of the company until 2001, but the government didn’t provide any more inputs during the development and growth of the company. The company’s achievements were all from its own efforts. Li Jingwei decided to move the headquarters of Jianlibao to Guangzhou in 1999; hoping to take this opportunity to reform the management, operation, personnel and advertising strategy of the company. He spent a large amount of money building a 38-floor Jianlibao headquarter building without consulting the opinions of the government, which deepened the mistrust between him and the Sanshui government. Meanwhile, the huge investment to the building construction reduced the availability of operational funds for Jianlibao. With the competition from foreign beverage companies, Jianlibao left the center stage with both internal and external difficulties. Li Jingwei lost all the business’s advantages and fell.

4.2.3 Promoting the Institutionalization and Professionalization of Enterprises

People normally think Chinese enterprises are ruled by man rather than ruled by law. Some people use “paternalistic headship” to describe Chinese enterprise leaders. The main features include a dictative style, unclear intentions, strong focus on personal reputation, maintaining control, engaging in politics, favouritism and nepotism, aggressive and aloof to subordinates etc (Westwood 1997). Similarly, some academics characterize the leadership style of Chinese organizations as paternalistic, which presents a father-like benevolence, authority and moral integrity in a personalistic atmosphere (Farh and Cheng 2000).

Most Chinese enterprise leaders depend on personal authority and virtue to lead their enterprises. This type of leadership has caused high centralization of power and low standardization inside enterprises, and encouraged the trend of sub-grouping. People who support this ruled by man style of leadership deem that its advantages are high flexibility, a simple structure, and high efficiency in decision making and executing commands etc. But they neglect the risks of this rule by man style. Firstly, leaders cannot always be correct. Leaders often become over-confident due to their success, and cannot get a second opinion because their staff have been trained to comply and compliment, or the excess centralization of power leaves them free to wield power without constraint – these all may inevitably cause wrong decisions by leaders. Secondly, because of excessively centralized power, top leaders make decisions according to their personal will and their personal likes and dislikes, and their organizations lack the necessary rules and regulations to control and coordinate their internal systems on an objective basis. These enterprises either do not have specialized departments or the specialized departments are skipped in the decision-making process. Leaders don’t delegate authority to their subordinates, and subordinates cannot participate in decision making. Employees in this kind of enterprises all try to develop personal relationships with leaders, gradually resulting in an organization where nobody is paying attention to the enterprise’s interests anymore. Instead, they ingratiate themselves with leaders to fulfill their personal interests. All this stops the healthy growth of enterprises, and ties their fate solely to their leaders. Once these leaders cannot run their enterprises anymore, due to age, sickness or accidents, or make wrong decisions, enterprises soon go down. This has become the destiny of many Chinese enterprises.

Another reason Chinese enterprises don’t think management institutionalization and standardization is important is that, during the fast development of enterprises, entrepreneurs think grabbing opportunities and occupying markets are more important than management standardization. They try to conduct institutionalization and standardization after enterprises are well established and stably running. But once the direction is settled, turning back and rebuilding standards is very difficult. Because of the lack of institutionalizations, enterprises are not able to run steadily and develop. They accumulate severe and lingering internal illnesses due to “black box” operation and decision making, and finally that illness causes their death.

Some entrepreneurs realized at the early stage of the economic transition that enterprises needed efficient and effective management systems and should be managed by systems and rules, not individual entrepreneurs. Lenovo started to set up rules and regulations in 1990 and requested employees to strictly follow the rules. Employees who disobeyed the rules would be punished without exception. In the 10 years from 1989, more than 10 people were referred to judicial authorities due to corruption. In order to strengthen the rules, Lenovo enforced rules at even quite micro levels from the beginning. The company requested no late arrivals for meetings. If somebody showed up at meetings late without prior permission, they would have to stand for a few minutes as punishment. The company’s founder, Liu Chuanzhi, himself was punished three times. Even though each time he had a reason, he still insisted on enduring the punishment. From Liu Chuanzhi’s perspective, people come together from different companies with different cultures, and the important thing is to make people realize that, once there is a rule, it must be obeyed (Liu 2009).

The CEO of www.hc360.com Guo Fansheng thinks leaders should create and improve systems to ensure the enterprise develops smoothly and sustainably. In order to motivate its employees, the company enforced a joint stock system from the very beginning. The company ruled the “bonus for single shareholders should not exceed 10 % of the total bonus, the bonus for shareholders should not exceed 30 % of the total bonus”, and “70 % of the total bonus should be given to employees each year as a labor share-out bonus”. Labor joint stock later evolved into knowledge joint stock. Twelve years later, when the company listed on the Hong Kong market, 126 employees became millionaires through their share holdings (Guo 2009).

Due to the fact that China had been developing a market economy only for a short period, managers and employees were all relatively low in professionalization, which limited the management and business capabilities of enterprises. Some entrepreneurs realized their employees were short in professionalism, so they strongly encouraged their employees to respect systems and procedures to ensure the stable and sustainable development of enterprises.

The Vanke Group established in 1984 and entered the residential housing business in 1988. Its founder, Wang Shi, insisted on gaining reasonable rewards from the market by offering professional capability. In 1992, nobody in the real estate sector would consider taking on a project if its estimated profit was lower than 40 %; however, Wang Shi claimed he would not undertake a project if its profit was over 25 %. He led his company to follow a standard, transparent, steady, and focused development mode. At the end of 2007, the company’s market share reached 2.1 %, and it became the biggest enterprise in the residential housing industry. Wang Shi has always focused on specialization and professionalization. He said: “A mature enterprise emphasizes corporate culture and mechanism instead of leaders. The function of leaders must be reduced. This is especially true for Chinese enterprises at the current stage. It is necessary for enterprises to separate from the entrepreneurs’ own life circles and develop. If an enterprise wants to develop long and far, establishment and enforcement of a mature running mechanism is necessary.” Being specialized and professionalized has resulted in Vanke’s business achieving constant development at a steady speed for many years.

4.2.4 Developing and Supporting Successors

Many entrepreneurs were middle aged when they started their businesses. After nearly 20 years of hard work, their health began going downhill, and the fast-changing environment also raised self-doubt about whether they still had the ability to match their ambitions. Some people are very autocratic, and subordinates can only listen to their demand. Under an autocratic leader, other people cannot participate in strategic decision making or run the core business, so grooming a successor is out of the question. Many people started their enterprises using their outstanding capabilities and strong willpower; however, it is these very same qualities that can cause enterprises to fall into “the founder's trap”.

Some entrepreneurs started fostering their successors early and were thereby able to set up the sustainable development of their enterprises. In general, the selection of successors follows three paths: internal fostering, external recruitment and family succession. Because the professional managers market in China is not yet mature, and the mechanism for regulating professional managers is not well established, almost no enterprises look for successors outside their own organizations.

In terms of fostering successors, Liu Chuanzhi is considered farsighted. In May 1988, Yang Yuanqing and Guo Wei joined Lenovo through open recruitment. Guo Wei was appointed as Public Relation manager right after joining the company and, 3 years later, Yang Yuanqing was appointed as general manager of the PC auxiliary equipment department. Yang Yuanqing actively promoted the “distribution model” used by Hewlett-Packard, and doubled Lenovo’s sales revenue during the year. In 1994, Lenovo established the PC department and Liu Chuanzhi appointed Yang Yuanqing as its head and also handed over to him full power to manage relevant R&D, manufacturing, sales, logistics and finance. Yang Yuanqing embarked on very bold reforms and was rewarded with significant achievements. But his approach was too tough and straightforward. He didn’t know how to compromise, which caused dissatisfaction among many of the original founders of the company. Being in the middle, Liu Chuanzhi used his skills to teach Yang Yuanqing how to manage his relations with the company’s seniors. One evening in early 1996, Liu Chuanzhi and other top management members convened a company meeting. As soon as the meeting started, Liu Chuanzhi started to criticize Yang Yuanqing very harshly: “Don’t take what you have now for granted, your platform today was built by us, we carried huge pressure…you cannot just close your eyes and go straight forward, and complain to me all the time about the unfairness you encounter. If you don’t learn to compromise, how can I keep doing my work?” Yang Yuanqing felt very mistreated and cried. He didn’t sleep all that night. The next day, he found a letter on his desk written by Liu Chuanzhi. In the letter, Liu Chuanzhi described very honestly how he viewed Yang Yuanqing as a person, and described the standards expected of someone wanting to be his successor at Lenovo. He also expressed the wish that Yang Yuanqing could behave in accordance with these standards as the future Lenovo leader (Ling 2005, pp 237–243). Liu Chuanzhi directly and frankly pointed out Yang Yuanqing’s problems, and instructed him on what to do to correct them. Yang Yuanqing gradually matured, and finally took over Lenovo. He likes to say: “Lenovo would not have what it does today if it only had my bold actions and not President Liu’s compromise back then.”

Many private entrepreneurs actively foster their successors, and have achieved a natural replacement of enterprise leaders. The list, “2009 young leaders of China’s private enterprises”, issued on Nov. 10, 2009, contained 103 enterprise leaders from the young generation, Of them, 31 of them were chairmen of the board, 13 were vice chairmen of the board, 15 were CEOs, 9 were deputy CEOs, 31 were general managers, and 4 were managing directors. Their average age was only 34. Among those on the list, 43 were from Zhejiang province, which demonstrated that region’s leading position in China in terms of the heritage of its private entrepreneurs.

As a matter of fact, the family succession mode, where children take over their fathers’ business, is very common in private enterprises. Founders of enterprises accumulate assets, social resources, working teams and the platform for developing, which lay the foundations for the next generation. The successors in a family business are normally those who have provided the biggest assistance to the founder, and who have been contributing to the growth of the enterprise. As the first generations grow old, the young leaders take over their fathers’ businesses, and continue to push forward the reform and transformation of enterprises, such as by clarifying the ownership, or establishing modern enterprise systems. Under this heritage mode, young leaders are given different levels of autonomy case by case.

The founder of WANXIANG Group, Lu Guanqiu, started his business in 1969. He captured opportunities, integrated domestic and overseas resources and led WANXIANG to success. He sent his son, Lu Weiding, to study business administration abroad for half a year after he graduated from high school. After Lu Weiding returned to China, Lu Guanqiu taught him by personal example as well as verbal instructions. He brought him along to meetings, took him to factories, and to meetings with clients etc., and had him work in different departments of the group. In 1994, Lu Guanqiu appointed Lu Weiding the CEO of WANXIANG Group. He gave Lu Weiding the automony to drive reforms and transformations within the company, while retaining for himself the control and guidance of the major direction and steps of the group based on his experience and wisdom. In order to prevent the new leader from becoming too adventurous, Lu Guanqiu set three investment prohibitions: no profiteering industries; no industry with too many competitors; no industry where the state operates. He convinced Lu Weiding to give up two acquisition plans under these prohibitions. Lu Guanqiu was fostering Lu Weiding’s professional qualification while continuing to control the strategic direction of the enterprise, playing the role of “stabilizer”.

Some private enterprises are co-founded by father and son. When the old generation retires, the new generation automatically takes over the business. The old generation’s complete retirement and handover of power leaves the new generation leaders completely autonomous in running the enterprises. Because the young generation leaders have gained rich experience on the job, they are well qualified to adjust their operational directions and modes in the new competitive environment, and head to new success. The founder of FOTILE Group, Mao Lixiang, started his business in 1985, and accomplished the first stage of development of the enterprise after 10 years of hard work. In 1995, he called back his son, Mao Zhongqun, who was about to go to the United States to undertake PhD study, to start a second business together. Mao Zhongqun convinced his father to give up the idea of the new business of manufacturing microwaves and, instead, proposed extractor hoods. When he joined FOTILE, he requested his own company with new teams, and with none of his father’s old work partners. After taking over the business, Mao Zhongqun pushed the enterprise forward with the introduction of independent branding and a professional manager system, and he led FOTILE to a new stage of development. Mao Lixiang surrendered his control over personnel, finances and decision-making and totally retired. He opened a training school to help small- and medium-sized enterprises complete succession management plans. He realized the older generation must give up power in order to create enough space for new generations to make full use of their talents. He says: “If I hold on to my power tightly, my son cannot grow, so he cannot develop his innovative business ideas. Some entrepreneurs are not willing to give up their power, even in their 1970s, so how can their sons take over the business in the future? Our first generation entrepreneurs must have this sense of responsibility and generosity.”

Hengdian Group followed a similar mode to that of FOTILE. Hengdian founder Xu Wenrong established Hengdian Reeling silk factory in 1975. He built Hengdian Group into a modern corporate base in the high-tech and movie industries through his strong will and intelligence. Xu Wenrong invented the “community owned” and “incremental joint stock” enterprise ownership system. In 2001, Xu Wenrong officially handed over the CEO position to his son, Xu Yongan. Xu Yongan had shown his talents in management and commerce long before. In bringing new products into production, he had achieved all the steps from preparing plants to production in only 90 days. Under his lead, the Yongan chemical factory grew into the Hengdian Debang Corporation from nothing, and became an important member of the 17 group members of the industry. Xu Yongan was also very good at capital operations and he helped his father to enlarge the business of Hengdian Group. After Xu Yongan took over as CEO, he emphasized capitalized operations and internationalized development. He took a completely different path from his father in enterprise management and development planning.

4.3 Professional Specialty Type: Focusing on Business, Creating Advantages

We are never afraid of core technology. If other people have it, I can do it as well; what other people don’t have, I have the courage to imagine it. Every time when a unit of BYD encountered problems, we would say: it’s not because of your capability that you cannot solve the problems, it’s because you lack the courage.

Wang Chuanfu

Since the late 1990s, the macro environment of China’s society has changed a lot. China started to build a comparatively optimized market mechanism and the Chinese people also started to understand the market better. Many local governments issued policies to support the local economy. Since China was changing from a shortage economy to a surplus economy, the capability and management quality of an enterprise became more important to its business. The growing market economy and the improved market rules washed out those enterprises only working on speculation or taking advantage of policies. Enterprises which could meet the demands of the market and had a core competency survived. Conversely, this made market competition more fierce. After China joined the WTO, most industries were completely opened, foreign companies received the same treatment as domestic companies, and many kinds of international companies entered the Chinese market, which further increased competition. In this mature market competition environment, integration of internal and external resources, efficient and effective management, as well as developing core competitiveness, were the key conditions for an enterprise’s success.

In this new market environment, the task facing Chinese entrepreneurs was no longer dealing with policy risks but focusing on enterprise management and increasing the core capacity of their enterprises. Entrepreneurs at this stage needed to analyze the trends of their industries, competitors, consumers, and technologies etc., formulate strategic directions for their enterprises, and organize the strengths and resources of their enterprises to implement the strategies. Integrating an enterprise’s control system, organizational structure, rules and procedures, and corporate culture to support the implementation of its strategies is a test for an entrepreneur’s management and organization capacity. During the past 10 years, a bunch of entrepreneurs emerged who had both high-level technical skills and sensitive market awareness. Even though, when they first started their businesses, they encountered difficulties in the form of insufficient funds and high technical barriers, they developed new markets by using their own innovations; and they are now leading Chinese enterprises to achieve the transfer from “China made” to “China created”. Most entrepreneurs appearing in this stage belong to the “professional specialty” type. They have in-depth understanding of enterprise management and operations, which mainly present as the following four aspects.

4.3.1 Accurately Managing the Strategic Positioning of Enterprises

Some Chinese entrepreneurs have been able to strategically position their enterprises accurately, based on the growth trends of their industries and market needs, and thus have set fundamental keys for the enterprises’ development.

After 20 years’ development, China Merchants Bank developed from a small bank in Shekou district of Shenzhen to a large scale bank with the 6th largest assets in China. As the leading group of China’s banking services, its achievement cannot be separated from a series of key strategic decisions made by its president, Ma Weihua. He was the first to transfer to retail banking in China, which won the bank a leading edge in the market. China Merchants Bank had fewer branches than other state-owned banks; however, Ma Weihua saw the opportunities brought by the Internet, and he took the lead in Internet banking in China. When China Merchants Bank was about to start a credit card business, a big international bank sought to issue a co-branded card with it. Ma Weihua and his team declined this offer, because they thought China Merchants Bank was not at the same level as this big international bank, and cooperation with this bank would constrain them. Instead, they decided to use a foreign management team. They developed China’s first standard international double-currency credit card, which was warmly welcomed by middle- and high-level consumers of China. It took only three and a half years for the bank’s credit card to grab 34 % of China’s credit card market, and rank first in average consumption per card.

In 1988, Wang Wenjing established UFIDA by taking the opportunity presented by the computerization of accounting in China. The financial software it developed took the leading position in the domestic market. Later, Wang Wenjing found some clients were using ERP system, which was a comprehensive enterprise management software. So Wang Wenjing set his teams working on management software, even though the company’s financial software was still their main product for revenue and retained a very good sales record. At that time, China’s management software market was occupied by SAP and other foreign companies. The ERP software developed by UFIDA, NC, was specially designed for Chinese enterprises, based on their management features and developing methods, which were different from the circumstances for which foreign ERP software was produced. First of all, many of the parent companies of state-owned enterprise groups were transformed from administration departments of the government; they had very weak control of their subsidiary companies. Secondly, many Chinese corporations were created from a combination of several enterprises, with capital, technologies, products and other important resources all controlled by subsidiary companies. There was a lack of coordination between parent companies and subsidiary companies, and between the subsidiary companies themselves. Most corporations ran various types of businesses, and the connections between these businesses were very loose; thus, intensified centralized control was necessary for managing those different types of businesses. Foreign software was designed for a single business management mode, which was not suitable for managing Chinese corporations’ loose multi-task businesses. Finally, foreign companies were normally good at specialization in a single business, but Chinese corporations were normally not so specialized. Therefore, management software designed by foreign companies could not fulfill the demands of Chinese corporations. UFIDA’s ERP product, which was specially designed for Chinese enterprises’ management demands, successfully broke the monopoly of foreign companies. Since 2006, NC’s growth rate has exceeded 40 % 3 years in a row. And for the first three quarters of 2009, NC’s revenue also increased by more than 40 %. So far, UFIDA has more than 4,000 clients, making it a clear No.1 in China’s high-level software market.

4.3.2 Thoroughly Understanding Theories and Practices of Enterprise Operation

Nowadays, people request operational standardization and management refinement of an enterprise; thus, entrepreneurs who have a thorough understanding of enterprise management theories, and are familiar with the good practices of foreign enterprises, as well as the operational practices of Chinese enterprises, can lead their enterprises to achieve success.

When the president of China Merchants Group, Qin Xiao, first took up his post in 2001, the total debt of the Group had reached 23.56 billion HK dollars, net profit was 44 million HK dollars, and non-performing assets were nearly 5 billion HK dollars. Often, the cash flow could not cover the interest on the debt. After 2 years’ restructure, the total debt of the Group had reduced to 14.16 billion HK dollars in 2003, the non-performing assets accumulated over its history were mostly sorted out by 2004, recurring profit reached 5.066 billion HK dollars, net profit reached 4.009 billion HK dollars, and the profit margin on net assets increased from 0.3 % in 2000 to 21.96 %. Qin Xiao attributed this success to his thorough knowledge of enterprise management theory and deep analysis of state-owned enterprises. He deemed that, previously, China Merchants Group had too many irrelevant businesses horizontally, which negatively affected coordination, and increased costs for internal coordination and management. Meanwhile, the organizational structure of multi-level corporate bodies derived vertically had elongated the management chain, and increased management costs, while also weakening the authority and capacity of headquarters in terms of resource mobilization and internal coordination. Based on the Transaction Cost Theory, Qin Xiao deemed that the existing organizational and business structure of China Merchants Group marketized the internalized transactions, which had been meant to reduce the cost, but resulted in the enterprise carrying double costs of internal management and market transactions. Further, he decided the market mechanism was overly used on the internal incentives and resource mobilizations of China Merchants Group, which destroyed the organization’s functions of mobilizing resources and coordinating transactions. Based on these understandings, Qin Xiao positioned the function of the headquarters of China Merchants Group as strategic decision making, and ended the situation of separated regimes within the group.

Fu Chengyu knew the developing trends of the petroleum industry very well after long-term practical experience in the business. After becoming president of China National Oil Offshore Corporation (CNOOC) in 2003, he proposed a development strategy that was “comprehensive, coordinative, and sustainable”. He declared: “there is no non-performing assets, only assets which are not being well used.” CNOOC Limited came onto the Hong Kong and New York markets in 2001, accounting for 3 % of its employees and 80 % of its assets. But what was going to happen to the rest of the employees and assets? Fu Chengyu solved this major hurdle to the reform of the state-owned enterprise by distribution listing, mutual support, and gradual revitalization. After CNOOC Limited was listed, he restructured and established two professional service companies using 37 % of the employees and 12 % of its assets. These two companies were also listed later. His purpose was to allow the petroleum company and the service companies to support each other. In 2004, he reorganized the remaining 60 % of the employees and the remaining 8 % of assets, which were considered bad assets, and structured a comprehensive supporting and service company. In the end, of the total 20,000 employees, no one was laid off or left waiting at home and the group returned to profitability in 2007. From 2004 to 2009, CNOOC’s sales revenue increased 312 %, profit increased 247 %, surrendered tax increased 631 %, total assets increased 338 %, and net assets increased 373 %. The two indicators, returns on net assets and returns on used assets, were the best in the global petroleum industry. Further, through independent innovations, CNOOC established a unique offshore oil development technical system. Fu Chengyu said: “The development of a state-owned enterprise needs internationalized insights as well as Chinese features. Copying others is not an option. An enterprise needs to explore its own specialties and potential; and, through reforms, turn political advantages into core competency. The development of CNOOC cannot only depend on one single company’s efforts; it needs marketization, professionalization, diversification, and collectivization to form a comprehensive force of the group, to become one fist. This is the unique competitiveness of CNOOC” (An 2010).

4.3.3 Creating a New Business Model

Some people have outstanding expertise or deep understandings of the needs of Chinese customers. Even though competition in their industry may be fierce, they still can stand out from the crowd due to their unique business models. This kind of entrepreneur mostly appeared in the new technology sector.

Internet search engine technology encountered a problem with cheating in the mid-1990s, when it was designed based on the word frequency statistic method. In order to promote their webpages or websites to the top of search results, webpage owners put words related to popular products in their webpages, even though they didn’t develop or produce that kind of product. In order to solve this problem, the founder of Baidu, Li Yanhong invented hyperlink analysis (ESP) technology. It is based on the number of times the content of a website is quoted to decide the ranking of the website in search results. This invention obtained a patent in the United States. Up until 1999, most mainstream search engines in the world adopted the hyperlink analysis technology.

In 2001, Li Yanhong proposed to transform Baidu from providing search techniques for portals to an independent search engine company, and to experiment with the PPC, or pay per click, mode. He adopted the PPC method, which charges clients based on the visits volume brought by Baidu. However, all shareholders opposed this proposal. Li Yanhong insisted on his plan, and finally convinced the investors. Since 2002, Baidu’s annual increasing rate on the revenue from PPC has reached 400–500 %. In 2008, Li Yanhong adjusted the business model again. He withdrew the software department of the company and gave up the portal mode to ensure the business development direction was in line with their core competitiveness. Baidu centralized nearly 70 % of its resources and time on the search business, which, on one hand, ensured innovation and, on the other hand, prevented its core business going in the wrong direction.

Wang Chuanfu established BYD Group in 1995. Now, its lithium battery business accounts for 60 % of the global market and 60 % of its manufacturing equipment is self-developed. At the beginning, when it produced nickel-cadmium batteries, one production line needed tens of millions in investment. Wang Chuanfu decided to separate the production line into manual procedures, which largely decreased the cost. In 2000, Wang Chuanfu decided to start producing lithium batteries. Because the equipment made by Japan was too expensive, he put the nickel battery production equipment on the lithium production line and they redesigned the incompatible parts. If some programs were unable to be redesigned, they would use tools to do it manually. BYD converted China’s low price but rich labor source to its cost advantage for the massive industrial production, which gave it the upper hand against its international competitors. Wang Chuanfu further transformed BYD’s unique production advantages into a vertically integrated capacity. It started from producing mobile phone parts, and gradually extended to mobile phone assembly and design; it provided a one-stop service from design to final production for Nokia and other clients. Compared with companies in the same business, BYD’s cost is 15–20 % lower for the same design, and one third faster.

As late comers, Chinese enterprises have to reference to the existing technology when conducting technology innovation. Wang Chuanfu legally avoided existing patents and broke the patent block by international enterprises. The intellectual property department of BYD constantly provided information to the technical departments regarding the patents which needed to be avoided. During its development of cars, the company took many foreign cars apart to study their techniques. They directly used the techniques without patents, and adjusted or avoided the techniques which had patents. The distinctive element of Wang Chuanfu’s approach was that he innovated by learning from other people’s outcomes, while avoiding lawsuits. In recent years, many international companies have accused BYD of infringing patents, but BYD eventually won all the cases in and outside China.

4.3.4 Having insight into the Needs of Customers

Since the mid-1990s, China’s market gradually transferred from a seller’s market to a buyer’s market. Along with the deepening and prevalence of the market economy, more and more enterprises started to engage in production and marketing. The kinds of products were varied, and merchants used all kinds of ways to attract consumers. China has said goodbye to a commodity shortage period, and many enterprises had to close down because of not being able to meet the consumer’s requirements. This kind of environment has forced enterprises to get to know the needs of customers, to make the products and services that can fulfill customers’ changing requirements, thereby presenting the advantages of the enterprises in competition.

Ma Huateng, the CEO and founder of Tencent Company, established his Tencent Empire on the foundation of a good understanding of customers’ needs. At Jan. 31, 2009, the number of people logging in to his QQ messenger service each month was more than 200 million; by June 30, 2009, people who registered accounts on its instant messenger reached 990 million person times, active accounts reached 448 million, and the highest number of people on line at the same time was 61.3 million, which was a world record at the time.

After graduating from college in 1993, Ma Huateng started in paging software development. Due to his good sense of marketing, a stock monitoring card he developed became popular in the market. After he got to know the ICQ instant messaging system, he thought it had major shortcomings: first, it didn’t support Chinese characters; secondly, messages on ICQ could only be saved at the user side, so, if the user logged in on another computer, the previously added friends would not be there; thirdly, users could only communicate online, there was no offline messaging function. In view of these shortcomings, Ma Huateng and his friends developed a Chinese version, OICQ, which later was renamed Tencent QQ. Tencent QQ can provide individual images for different users. It takes up little space and is easy for users to download. QQ’s competitor, MSN, only had these features years after. Ma Huateng understood his customers very well; he merged his experience and needs into the product design. He positioned himself as the chief designer and chief experiencing officer, spent large amounts of time on testing all the products and services, trying to gauge the feelings of customers. Tencent gives very prompt replies to customers’ requests. Tencent has special teams collecting customers’ opinions on different forums, and it also invites its “fans” to try their new products, and uses various means to monitor and assess customers’ experiences. The company also established a customer experience and design center, which has experience rooms, and carries out comprehensive training and assessments on user experience. Ma Huateng and his teams have been able to develop software and services which are suitable for Chinese internet users because of his correct understanding of customers’ characteristics. All these high “user stick” products created a big and dynamic user group, which has brought the enterprise generous profits.

4.4 The International Operation Type: Venturing Out of China, Facing Challenges

The best way to deal with the challenges coming from multinational corporations is to become a multinational corporation. If you are “dancing with wolves”, you have to become a “wolf”, otherwise there will be only one outcome: be eaten.

Zhang Ruimin

Our guerrilla style is not completely gone, the internationalized management style is not yet formed, and the level of the professionalization of our staff is still low, we are not yet equipped with the capacity to gallop in the international market; as soon as our ship sailed into the ocean, problems occurred.

Battling in the overseas market, we should get familiar with the market, win the market, foster and train our management teams…if we cannot build up an internationalized team in three to five years, once the Chinese market is full, we shall just sit there and wait for death.

Ren Zhengfei

Entering the twenty-first century, Chinese enterprises accelerated their venturing out of the country. Some enterprises started joining the global industrial division or participating in competition in the global market. After more than 10 years’ implementation of a market economy, the markets of some industries were showing signs of saturation, with excess production capacities. The extremely fierce competition resulted in less and less market opportunities and profits. After nearly 20 years’ development, some enterprises already have accumulations in terms of capital, technologies and operational management. Since China joined the WTO, the barriers for Chinese enterprises to enter the international market have reduced. All these provided positive conditions for the internationalization of Chinese enterprises.

The internationalization of an enterprise requires core competitiveness. In order to participate in international competition, enterprises need to be equipped with standardized management, specialized techniques, and talents with international perspectives and experiences. Leaders of these enterprises seized opportunities during China’s economic transitional period: they gradually identified the business directions during development, occupied the domestic market with their unique products and successful business operation models, and eventually led their enterprises to expand outside the country. They belong to the “international operation type” of entrepreneurs. They have the following characteristics.

4.4.1 Promoting Innovation, Building Competitive Advantage

In some freely competitive areas, local enterprises encountered pressure once international enterprises stepped into the market. Enterprise leaders had no safety zone to retreat into and had to fight. They developed their own techniques and services, firstly carrying on business in local areas and achieving the acknowledgement of customers, and then investing their profits in research and development, gradually building up their competitiveness. For example, since the 1990s, the network operators of China Telecom mostly used the equipment of international companies, such as Sony Ericsson, Nortel Networks, Alcatel, and Siemens etc. ZTE, HUAWEI and other Chinese companies conducted research and development, as well as effective market explorations in telecommunications and gradually improved the performances of their products to near that of the international companies. They then grabbed the market advantage using their lower cost and prompt services.