Abstract

This chapter traces the urban employment trends in cultural industries in the Netherlands from 1899 onwards and argues that a historical approach is necessary to understand economic geographical patterns in this post-industrial growth sector. Longitudinal employment data for the country’s four main cities, as well as case-study information on the spatial and institutional development of separate cultural industries in the Netherlands, reveal long-term intercity hierarchies of performance and historically-rooted local specializations. The effects of historical local trajectories on the inter-urban distribution of Dutch cultural production are weighed against more volatile factors such as creative class densities. Implications for the general outlook and development of these post-industrial urban economies are then explored, whereby the connectivity of the cities in international and regional networks is taken into account. The chapter concludes with identifying the evolutionary mechanisms at work in Dutch cultural industries and the value of a historical perspective vis-à-vis other geographical approaches to the urban cultural economy. As the four examined Dutch cities are all part of the Randstad megacity region, the dynamic Dutch urban cultural economy represents an unlikely case for stable inequalities between cities based on local trajectories. Consequently, strong implications may be inferred for cultural industry dynamics in other contexts.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Postindustrial urban economy

- Cultural industries

- Path dependency

- Competitiveness

- Megacity region

- The Netherlands

1 Introduction

Under pressure of globalization, urban economies have had to undergo processes of restructuring over the past few decades and cities in high-wage Western countries such as the Netherlands have had to reposition themselves in a globalizing economy. Failure to do so is often held responsible for local economic stagnation and the rise of urban social ills. In recent years, societal developments associated with globalization, such as immigration issues, European integration, neoliberalization, and a perceived loss of national identity and social cohesion, have become strongly politicized in European countries (see for example Scheffer 2007). In the Netherlands, a small country with a traditionally open economy, this has led to an increasing polarization between ‘cosmopolitans’ and new right-wing populist parties that have taken up a fervently nationalist and anti-immigration stance, echoing increasingly-vocalized popular discontent regarding the effects of globalization.

In this polarizing process, new geographical divisions have emerged within the Dutch political landscape. A divergence has occurred between the country’s four largest cities in terms of prevalent political attitudes. Whereas voters in the capital Amsterdam and in Utrecht, the smallest of the four cities, have so far generally sided with the cosmopolitan camp, Rotterdam and The Hague have drifted into the potentially murkier waters of nationalistic sentiment and growing inter-ethnic tension. The political divergence between Amsterdam and Rotterdam, particularly, is striking, as these two cities, the largest in the Netherlands, were both considered traditionally as left-wing labor-party strongholds. Conversely, The Hague and Utrecht have historically upheld a more conservative profile. But these latter two cities as well seem currently to be diverging towards opposite ends of the political spectrum.

The ethnic composition of the urban population is fairly similar in these four cities. Commentators such as the political scientist Mark Bovens have therefore concluded that the political divergence between the cities, and their differing levels of cosmopolitanism, is related to other factors, namely local levels of education and, especially, the extent to which the different cities have been able to produce and attract ‘winners’ rather than ‘losers’ of globalization (Volkskrant 2008, 2009; Trouw 2009). Because ‘success’ in these cases is mostly defined in terms of economic opportunity, and economic prospects of different sectors vary widely in the context of globalization, the political divergence is ultimately being related to differences in the economic profiles of these cities and their orientation on different sectors of the economy.

Presently, the so-called ‘cultural industries’, the producers of aesthetic or symbolic commodities, are often assigned a pivotal role in aligning post-industrial urban societies with the new economic and social realities of globalization. For this reason, many national and city government try to stimulate cultural production, such as architectural design, publishing, or media broadcasting, in their cities. But much remains unclear about the social role and the economic and geographical dynamics of cultural industries. Does a thriving local cultural industries sector guarantee or even indicate healthy economic and social development of a city in a globalizing, post-industrial context, enhancing the city’s prospects of sustainable economic growth and offering its urban underclasses (often consisting mainly of immigrant groups) the opportunities of social mobility? Or do these industries, as some commentators suggest, present cities with an illusionary and ephemeral economic basis (Peck 2005) and reflect the bankruptcy of local cultural authenticity and cohesion (Cf. Lampel and Shamsie 2006), or even the social ills and economic dead-endedness that are sometimes believed to inspire true art (Cf. Hall 1998; Scott 2007)?

There has also been debate about the ability of public interventions to effectively and positively stimulate the development of local cultural industries. It is sometimes claimed that cultural industries generally evolve incrementally according to long local historical trajectories. Long local histories in particular forms of cultural production enable the slow development of expertise and the build-up of valuable networks and reputations that may be required to compete successfully in these industries. It is therefore unclear to what extent competitive cultural production can be set up on a short-term basis in places where already well-established, pre-existing ‘art worlds’ (Becker 1982) are lacking. Some cities may simply be better historically conditioned than others to compete in cultural industries, so that little can be done to change, instantaneously, the ‘cultural potential’ of a city. It thus remains to be conclusively shown if cultural industries are as imminently desirable as they are often made out to be, and also whether or not the short-term creation of a vibrant cultural industries scene is feasible in every city.

This paper aims to provide insight into both these questions by examining the recent state of the cultural industries in the four largest cities of the Netherlands as well as the long-term historical dynamic of these industries in the Netherlands throughout the twentieth century. This will show whether or not the Dutch cities that currently enjoy a relatively good or improving position with regards to cultural production are the same as those that display greater levels of cosmopolitanism, economic optimism and social stability. It will also show whether these positions have remained fairly constant over the twentieth century, and are thus likely to be historically conditioned, or have been subject to major shifts, in which case the fortunes of a city’s local cultural industries may perhaps change or be changed fairly easily.

The Dutch case is particularly interesting in this regard for two reasons. First, the political shift towards nationalism in the Netherlands has surprised Dutch and international commentators alike because this country was previously considered a champion of multiculturalism and cultural liberalism (Entzinger 2003). Secondly, the geographical dynamic of cultural industries in the Netherlands provides a good window unto the weight of local history in determining the strength of local cultural industries. Many cultural industries have century-long histories in the Netherlands. Furthermore, and more importantly, the Netherlands is a highly polycentric country which lacks a single, ‘natural’ metropolitan and cultural center. The four cities that are examined here, are in fact all part of the larger conurbation called ‘the Randstad’ that is often regarded by urban planners and geographers as a paradigmatic example of a multi-nuclear urban region (Hoyler et al. 2008; Lambregts 2008). The cities are thus all relatively close together and interconnected so that mobility between them is relatively easy, for producers as well as consumers of cultural industries. Nevertheless, each city has its own historically formed and distinct local character. This case thus enables an assessment of the importance of differences in local characteristics under conditions of strong interrelatedness that make the potential for inter-urban redistributions of activities relatively high.

2 The Promise of Cultural Industries and Their Geographical Dynamic

The transition to a post-industrial and globalizing economy during the last few decades of the twentieth century has had several main effects on Western cities. First of all, a general economic resurgence of cities seems to have taken place, with new service- and consumption-led activities concentrating mainly in metropolitan areas (Zukin 1995; Scott 1998). This resurgence has fueled processes of gentrification and a new flow of domestic as well as overseas immigrants into the prime urban areas of Western countries, largely reversing earlier trends of urban decay, rising unemployment and the flight of urban middle-classes to suburban areas. Secondly, new social tensions and forms of economic, social and political polarization have emerged. According to sociologist Saskia Sassen especially ‘global cities’, the central service nodes of the globalized economy, have seen their labor markets polarize to the extent that the increase in low-end unskilled service jobs, mostly filled by foreign immigrant groups, as well as in high-end positions in advanced producer services firms, has largely eliminated the availability and economic significance of intermediary forms of employment. This gradual disappearance of middle-of-the-road jobs has increased barriers to upward labor mobility, as entry into higher strata of the metropolitan labor force now requires a substantial ‘leap’ in terms of (especially) education, and the option of a gradual climb up the labor ladder is no longer available in many cases (Sassen 1991).

Despite the social dangers accompanying labor market polarization, policymakers and academics have generally aimed to stimulate post-industrial development in cities. One reason for this attitude has been that few alternatives exist for urban economies in high-wage countries, as standardized manufacturing activities have been increasingly off-shored. Cities that have not managed to adapt well to the new economic circumstances, especially former centers of manufacturing such as Detroit, have experienced stagnation and worse social ills than those associated with global cities. It is within this general political and economic context that countless city councils have been keen to accept as policy paradigms new theories of urban economic development revolving around the ‘creative’. Richard Florida’s notion of the economic importance of attracting the so-called ‘creative class’ and Charles Landry’s concept of the ‘creative city’ have led to the formulation and implementation of generalized recipes for stimulating the local ‘creative economy’ of cities (Florida 2002; Landry 2000). These recipes seem to have been interpreted in many cases as a type of policy panacea (cf. Martin and Sunley 2003), although (needless to say) they have not proven their effectiveness in every urban setting (Peck 2005; Markusen 2006). Attempts to refine formulas for stimulating the urban creative economy (that has become something of an urban policy Holy Grail) have continued and have usually accorded a central role to cultural industries, fields of production that generate goods and services that derive their value mainly from their aesthetic and symbolic characteristics rather than from their use-value (Scott 2000; Kloosterman 2004).

Cultural industries have attracted much attention from policymakers and academics alike because employment in these industries has grown rapidly in recent decades. For this reason, they are considered (potentially) important pillars of postindustrial urban economies (Kloosterman 2004). As prime creators and conveyors of aesthetic and symbolic value, these industries are also valued for their potential positive spillover effects on other economic sectors that need to adapt their products to more general trends of a ‘culturalizing economy’ that places an increasing premium on the aesthetic appeal of goods and services, and on the consumer experiences products induce (Lash and Urry 1994). Furthermore, cultural industries are prized for more than their economic potential. The artistic element of cultural industries is considered instrumental in efforts to regenerate decrepit inner-city neighborhoods both socially and culturally (Scott 2007). With such reputed positive economic and social externalities associated with urban cultural industries, it is not surprising that this sector is deemed worthy of public investment and intervention.

Much recent research into the geographical dynamics of cultural industries, however, suggests that active policy-intervention aimed at stimulating competitive cultural production may not be sufficient to provide the preconditions that these industries need to flourish, especially not in cities where policymakers cannot build on an already well-developed and established cultural scene. Economic geographers such as Allen Scott and Andy Pratt have argued that cultural producers often depend on local ‘art worlds’ to perform competitively. Unlike Richard Florida, they regard ‘creativity’ as the outcome of complex social interactions involving many different actors engaged in related activities, rather than as an innate characteristic of a specific ‘class’ of individuals (Scott 2000; Pratt 2008). Complex specialized production systems of interdependent artists or designers, distributors, retailers, critics, trainers or teachers, specialized material suppliers and many types of industry-specific services underpin competitive cultural production. Such production systems are usually localized as they emerge from intense interactions that often require actors to be in close proximity to each other. Just as in high-technology industries such as computer software production therefore, cultural industries producers agglomerate in clusters, unusual spatial concentrations of related economic activity (Saxenian 1994). Hollywood (and Bollywood) film production, Broadway theater and Milan fashion are prime examples of the tendency of cultural industries to form their own industry-specific hotspots and ‘Silicon Valleys’ (Scott 2005; Wenting 2008).

The concentration of specialized firms, producers, artists, facilities and institutions, that make clusters such as Hollywood the ‘place to be’ for a specific cultural industry and enable competitive cultural production, has to evolve over time. Through collaboration as well as vigorous competition, different firms and institutions in a cluster provide each other with incentives for ongoing specialization. Furthermore, they need to adapt their expertise and practices to one another to reap the full benefits of being located close together, or simply to keep up. The different actors in clusters thus collectively form ‘ecologies’ that are not simply created but grow and develop interdependently (Grabher 2001). The cluster model implies that cultural industries become entwined with and rooted in specific cities. The success of a local cultural industry therefore often depends and builds on the historical development of that industry in the city in question. This means that some cities may be better suited than others to compete in specific fields of cultural production by virtue of the weight of history and the local presence of complex, ‘organic’ networks of producers supported by ‘thick’ webs of specialized institutions (Amin and Thrift 1995) that took a long time to develop and are hard to copy elsewhere in the short-term.

If cultural industries indeed develop primarily in clusters, strong historical continuity in the geographical distribution of particular types of cultural producers may be expected. Although the evolutionary cluster model is theoretically sound and empirically supported by a host of case studies (e.g. Rantisi 2004; Van der Groep 2008; Kloosterman and Stegmeijer 2005; Kloosterman 2008), studies that systematically map the long-term geographical dynamic of cultural industries growth are scarce (cf. Wenting 2008). To help this dynamic, this paper thus sets out in the following sections to empirically examine to what extent the distribution of employment in cultural industries between the four main cities in the Netherlands has changed since 1900. The long-term evolution of the relative positions of the four major cities in the Netherlands will be determined for the cultural sector as a whole, and for several different key cultural industries separately, with the use of both quantitative employment data and qualitative information concerning the development of Dutch cultural industries. Before these findings are presented, however, a short description of the four cities in question will be provided, as well as a preliminary analysis of the general fortunes of the cultural sector on the national scale from 1900 onwards.

3 The Four Largest Cities of the Netherlands

3.1 Amsterdam

Amsterdam is the largest city in the Netherlands and the country’s capital, although it does not hold the seat of government. The city experienced strong growth during the country’s Golden Age that started during the last decades of the sixteenth century, when the Dutch started a successful national revolt against their Spanish overlords, and lasted until the beginning of the eighteenth century. The city profited strongly from a naval blockade of the Schelde River that gave access to Spanish-held Antwerp, Northern Europe’s largest and most prosperous port city at the start of the Dutch Revolt. Many Antwerp merchants, artist and intellectuals fled to Amsterdam, contributing to a period of prolonged economic growth that turned the city into the center of an extended overseas trading empire. At the start of the seventeenth century, the world’s first stock exchange and the first multinational corporation (the Dutch East India Company) were founded in this city that consequently became the heart of Europe’s financial networks. During subsequent decades, Amsterdam expanded physically through the creation of a planned canal belt that is presently a candidate UNESCO World Heritage site and earned the city the reputation of being ‘the Venice of the North’. Simultaneously, Amsterdam became an important European center of culture, with painters such as Rembrandt and philosophers such as Baruch Spinoza achieving long-lasting international fame. The city’s art markets and book trade industry developed rapidly and its painters and publishers exported widely throughout Europe. The city also became very attractive to new groups of foreign immigrants. Foreign intellectuals such as Rene Descartes and John Locke spent part of their working lives in Amsterdam. Many skilled and unskilled temporary immigrants came from the German territories, Scandinavia, and France and were drawn to the city by its booming economy. Furthermore, two groups that were prosecuted on religious grounds in their home countries, French Protestant Huguenots and Iberian Jews, settled permanently in Amsterdam as this relatively tolerant city afforded them religious liberties and plentiful economic opportunities.

Presently, Amsterdam is the Netherland’s financial and business center as well as the country’s main tourist destination (Engelen and Grote 2009; Bontje and Sleutjes 2007). By virtue of its many internationally operating firms and cultural influence, Amsterdam is considered an ‘incipient global city’ of similar standing to Boston, Milan and Moscow (Taylor 2005). It is the eighth most popular tourist city in Europe (Bremner 2007) and its airport Schiphol is Europe’s fifth largest (Airports Council International 2008). The city owes its world-wide cultural appeal partly to its Golden Age heritage, with the paintings of Rembrandt and other ‘Dutch masters’ as well as the city’s renowned canal belt attracting many tourists. Another important aspect of Amsterdam that has shaped its international image, is the strong cultural permissiveness and liberalism that has come to the fore since the 1960s and manifests itself most clearly in the city’s infamous Red Light District, its marihuana-selling coffeeshops, and its lively and open gay scene.

3.2 Rotterdam

Rotterdam is the country’s second largest city. It is located at the mouth of the Maas river (a main artery of the river Rhine) and contains Europe’s busiest port. Although the city was already home to the philosopher Erasmus around 1500, it long remained a relatively stagnant town. This changed in the nineteenth century when trade with England and German economic growth, concentrating especially in the Ruhr-Rhine region, stimulated much port activity. Rotterdam thus profited strongly from the industrialization of neighboring countries. The city quickly expanded and started to rival Amsterdam in terms of its size and population. The city and its surrounding region became a hotbed of (heavy) industrial activity and during the twentieth century Rotterdam became one of the country’s strongholds of socialism and union organization.

In 1940, the city was targeted by German bombing raids in the Nazi’s effort to subdue the Netherlands. Its historic city center was all but destroyed. Since then Rotterdam has been rebuilt and now possesses one of Europe’s most modern inner cities, containing skyscrapers and an innovatively designed shopping area (Kloosterman and Stegmeijer 2005). Throughout its postwar physical transformation, Rotterdam’s economy has remained oriented towards shipping and manufacturing. The city has therefore suffered from processes of deindustrialization which have produced rising unemployment and crime rates, as well as rising social tensions between its native-Dutch population and immigrant groups. Rotterdam is currently one of the major focal points in the country’s increasing political polarization, with populist, nationalistic parties receiving much support in the city. In attempts to spur the city’s economy and abate social tensions, successive national and local governments have invested heavily in Rotterdam’s physical and cultural infrastructure over the last three decades. New museums, cultural institutions and festivals have been set up, and feats of iconic architecture have been financed, as a means to raise Rotterdam’s cultural profile and to make the city more attractive to foreign investors and innovative entrepreneurs.

3.3 The Hague

While it is not the country’s official capital, The Hague, the Netherlands’ third largest city, holds the national seat of government. Due to the presence of the country’s main royal palace The Hague is known as the ‘court city’. It is the center of Dutch politics and houses the country’s ministries and parliament as well as countless foreign embassies. It is consequently home to many civil servants, lobbyists and legal experts. At least since the The Hague Peace Conference of 1899 the city has been at the forefront of the evolving system of international law and arbitration and it has hosted the International Court of Justice from 1946 onwards. The Hague’s position as political center has its roots in medieval times when the counts of Holland used the city as their administrative center and court. When, during the seventeenth century, this region became Northern Europe’s most prominent economic powerhouse, the Province of Holland (which comprised the two present-day provinces of North and South Holland that include Amsterdam and Rotterdam respectively) became dominant in the country’s affairs and its age-old administrative center attained a status similar to that of national capital.

Due to a geographical position, away from major rivers, that inhibited maritime access the city lagged strongly behind Amsterdam in terms of population growth and economic prowess. At the start of the nineteenth century, the former Dutch Republic became the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the monarch’s court as well as a national parliament were established in The Hague. The city grew in tandem with the scope of the national administration and attracted wealthy (and particularly aristocratic) elites that drew in many types of servants in their wake. Henceforth The Hague’s economy revolved mainly around the needs and leisure of the city’s elites. An adjacent, poor fishermen’s village (Scheveningen), for example, was turned into an elite beach resort. The city’s economic orientation largely kept out heavy manufacturing industries, and generated one of the widest social-economic divides in the Netherlands. This division is still manifest today, as The Hague boasts some of the richest, as well as some of the poorest neighborhoods in the country (NRC 2006).

3.4 Utrecht

Utrecht is one of the oldest cities of the Netherlands and was founded by the Romans. It lies close to the geographical center of the country and along the main branch of the river Rhine. Since early medieval times, the city has held an archbishopric seat and has lain at the heart of the episcopal hierarchy in the Netherlands. This Catholic significance of Utrecht was interrupted when in the sixteenth century Protestants took control of the country, but was re-established in the nineteenth century when a new liberal constitution guaranteed religious liberty. Since then, the city has again become a main center for the country’s Catholic clergy.

Due to its favorable geographical position, the city has become in the twentieth century the main hub of the country’s busy railway system and road network. This hub-function has made Utrecht attractive to businesses, commuters, students and day trippers alike. The city has therefore gained strongly in terms of its population and economic significance over the course of the twentieth century. It has also attracted a large foreign immigrant population. Yet inter-ethnic and other social tensions have remained relatively mild. Utrecht is now considered, just like Amsterdam, to be one of the most ‘cosmopolitan’ cities of the Netherlands (Trouw 2009), and among its inhabitants one finds, more often than in many other cities, the ‘winners’ of globalization.

4 Just a Fad? The Growth of Cultural Industries in the Netherlands Since 1900

During the twentieth century the Dutch economy underwent fundamental economic transformations. Around 1900 agriculture still provided work to around 30 % of the Dutch labor force and traditional crafts still played a substantial role in terms of employment, next to trade-related activities and industrial manufacturing (Van Zanden 1997). At the start of the twenty-first century by contrast, agriculture and manufacturing taken together account for no more than around twenty percent of total employment (CBS 2007: 12). While the Dutch economy was never as outspokenly industrial as Belgium’s, for example, the services sector dominates in present-day the Netherlands like never before. How have the cultural industries developed throughout this century that first saw the Netherlands increasingly industrialize and then, after 1960, deindustrialize.

The following three figures provide a rough indication of the twentieth-century growth of the Dutch cultural economy by comparing the development of employment in economic branches that include cultural industries professions with the growth of employment in the wider economy. In order to stress the relevance of urban as opposed to rural economic activity, employment in agriculture and fishing has been left out of the comparison.

The systems of industrial classification used by the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics for its economic surveys and corporate censuses, do not always enable a firm handle on developments in the cultural industries. Especially between 1930 (when an extensive nation-wide occupational survey was held) and 1993 (when a renewed and extended system of classification was introduced) few specific data on these industries are available. The figures thus largely reflect a fairly rough estimate based on data concerning employment in several wider corporate categories such as ‘the liberal professions’ and ‘business services’ in which cultural industries were presumably best represented. Because of the changes in the systems of industrial classification used (as well as in the system of geographical subdivision that defined economic geographical units for administrative purposes), the comparison between general employment growth and employment growth in economic fields that may serve as proxies for the cultural industries has been subdivided into three distinct periods. More specific research into the growth of eight emblematic cultural industries in the Netherlands between 1993 and 2001 has produced results similar to those displayed in Fig. 15.1c, thereby confirming the relative accuracy of the proxies used here (Kloosterman 2004).

Despite the shortcomings of this initial overview, it is clear that the growth of cultural industries in the Netherlands is not exclusively a recent phenomenon. Insofar as conclusions may be drawn from these preliminary data, this analysis indicates that employment in cultural industries (or at least in related sectors) rose at higher rates than employment in the Dutch (urban) economy as a whole during most decades of the twentieth century, apart from the 1920s. The relatively fast rises during the periods 1899–1920, 1930–1950 and 1980–1988 are quite surprising as these were all relatively difficult periods for the Dutch economy, involving much political and economic restructuring. It seems therefore that, for a relatively long time already, cultural industries have formed an attractive alternative to other, failing forms of enterprise in the Netherlands. Employment in activities focusing on cultural production has thus become steadily more important for the Netherlands as a whole over the last 100 years, albeit in leaps and bounds.

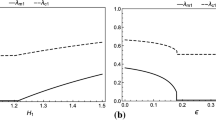

5 Urban Positions in the Dutch Cultural Economy

Did the growth of this steadily increasing cultural economy take place primarily in the country’s four largest cities? And were different cities more prominent within the Dutch cultural industries at different times during the twentieth century, or was there continuity in the ‘cultural hierarchy’ between cities throughout this century in which the economy, society and culture all underwent great changes? In order to answer these questions, location quotients of employment in the cultural sector have been ascertained for the four cities for different years during the period studied. These location quotients (LQs) represent the share of the cultural sector in each city’s local economy divided by the share of the cultural sector in the national (non-agrarian) economy as a whole. They are based on the same employment data analyzed above, only now this data has been differentiated per city. As such, these LQs allow us to see whether specific cities are disproportionally represented in these industries at different times by showing whether the share of their workforce that is employed in the cultural economy is above or below the national average.

Figure 15.2 shows that, by and large, this growing sector was concentrated disproportionally in the major cities, and particularly in Amsterdam, throughout the period 1899–2005. In 1899 and 1920, as well as from 1973 onwards, the creative sector was relatively better represented within the Amsterdam economy than within the economies of the three other cities. Only in 1930 and 1963 did The Hague’s creative sector outperform Amsterdam’s in terms of its prominence within the local urban economy. Rotterdam displayed a continuously mediocre orientation on this sector throughout the twentieth century, and only started to slightly outperform the national average in 1980. Improvement in Rotterdam coincided with relative decline in Amsterdam and The Hague. Furthermore, Rotterdam’s fortunes improved at a time when a dynamic architectural scene started to emerge in Rotterdam, following the establishment the Office of Metropolitan Architecture (the design agency of the famous architect Rem Koolhaas) and the National Architecture Institute in the city (Kloosterman and Stegmeijer 2005; Kloosterman 2008). The data found on Utrecht unfortunately do not cover the entire period under study but do indicate a fairly continuous slight overrepresentation of the creative sector in the local economy.

The positioning of the four cities relative to each other in the creative sector has varied throughout the century, but only slightly so. The creative sectors in Amsterdam and The Hague outperformed those in Rotterdam and Utrecht in the past, and still do so in the present. Usually Amsterdam held top rank. There do not seem to have been many instances in which major redistributions between the four cities took place. In terms of their ‘creative fortunes’, the hierarchy between the four cities thus appears to have remained largely intact since 1900.

6 Separate Cultural Industries

The cultural industries include a wide array of fields of production, ranging from publishing and the graphic industry to theater to the clothing industry. What these industries have in common is that they dictate styles, need to innovate continually, and produce as commodities the beauty or symbolism that we refer to as cultural. In all cultural industries, value is created mainly through the appearance, presentation and aesthetic impact of products and services rather than through their functionality. However, when it comes to their geographical dynamics and relations to places (and place-specific historical trajectories), important differences exist between these industries and distinctions can be made between them along different dimensions.

The degree of product mobility, for example, differs per industry: books are more easily transported than theater performances. The content, as well as the form, of products determine their mobility as some products cross national or cultural boundaries more easily than others. Products bound to languages that are spoken in modest linguistic areas, such as Dutch, are unlikely to reach international markets, and may be expected to be less sensitive to global market developments and competition than products that travel more easily across linguistic boundaries. The height of entry barriers also differs per industry. Activities such as film production generally require relatively high initial investments whereas the production of paintings often does not.

Differences such as these may influence the degree to which production in a specific cultural industry is place-bound. Some branches of the cultural economy may therefore be less amenable to local policies, or vulnerable to local developments, than others. To gain a fuller understanding of the rootedness of cultural economic activity in particular Dutch cities, the geographical distribution and long-term geographical dynamics of separate cultural industries in the Netherlands will be compared here. This comparison may also contribute to discussions regarding breadth of economically-productive ‘creativity’, as it will show to what extent, within the Dutch context at least, local creative prowess spills over from one cultural industry to another. If all cultural industries concentrate equally in the same cities, then a general artistic atmosphere is a valuable asset in a city’s economy and efforts should be made to enhance such an atmosphere and attract and retain ‘creative’ people. If, on the other hand, separate industries are distributed differently across cities and display fairly autonomous dynamics, that would indicate that cultural industries thrive on local specialization and on industry-specific practices, expertise and institutions that presumably take time to evolve.

A preliminary categorization of the field of cultural production will guide the following discussion of separate cultural industries. The cultural sector is sometimes divided into three categories: (1) Arts, (2) Media and entertainment, and (3) Creative business services. The first category includes literature, music and the visual and performing arts, the second contains broadcasting, film production, computer games and the publishing industry, while the third category refers to activities that add symbolic or aesthetic value to functional goods and services produced in other industries. Creative business services thus include architecture, advertising, design and fashion. These categories tend to correspond to different types of industry organization and market orientation (Pratt 2004; Bontje and Sleutjes 2007; Stam et al. 2008), a point which will be elaborated in the rest of this section. To these three existing categories, a fourth will be added here to better reflect historical diversity in this long-term overview of the production of cultural commodities. This fourth category, the creative crafts, covers industries that involve the manual production or manipulation of aesthetic objects and that have largely disappeared (in their traditional form) as significant sources of employment in the Netherlands.

7 The Creative Crafts: Diamond Cutting, Garment Industry, and Arts and Crafts

The creative crafts include industries such as jewelry making and diamond cutting, watch making, arts and crafts, and the garment industry insofar as it involves manual production and customized tailoring. In most of these industries, traditional forms of manual, short-run (or one-off) production were increasingly replaced by automated, standardized mass-production over the course of the twentieth century. As such they have lost many of their original creative qualities (Cf. Glasmeier 1991, 2000). By and large, craftsmanship is no longer required in these industries’ productive processes, and in many cases production has been outsourced to low-wage countries (see for example Rantisi 2004). Consequently, these industries have lost nearly all of their significance for the Dutch economy and hardly retain a presence on Dutch urban labor markets. The aesthetic design of products is now usually separated from their physical production. Through processes of increasing division of labor, both in the organizational and geographical sense, product design and product realization have become separate tasks, often performed by different firms in different places.

During the first half of the twentieth century, however, these tasks were often still intimately related, which is why creative crafts are considered cultural industries in this overview (see also Scott 2000). An analysis of the spatial patterns of these creative crafts may contribute to more general insights about the geographical dynamics of cultural industries and the factors that support their growth in specific places. Furthermore, some of these industries may have left significant traces on the Dutch cultural economy, by stimulating local design activity for example. They may thus have played important formative roles in present-day cultural industries and may have influenced continuing historical trajectories of the cultural economy in certain cities.

7.1 Garment Industry

The textile industry was one of the main generators of nineteenth-century processes of industrialization and automation, but the manufacturing of clothes long remained a fairly craft-like activity. It often took place in small workshops rather than in large factories. Garments were produced in direct collaboration with retailers in order to cater to the specific demands of individual customers or to be able to respond to the latest fashions (Rantisi 2004; Breward and Gilbert 2008). Until the 1960s, when international competition put increasing pressure on Dutch garment producers, the garment industry formed a large and important sector in the Netherlands. In 1899 it accounted for around seven percent of total non-agrarian employment in the country, and in 1963 still accounted for nearly four percent. As can be seen in Fig. 15.3, the industry was of still greater importance for the Amsterdam economy; up until 1930 the industry was also overrepresented in Rotterdam and The Hague. The industry declined rapidly from the 1960s onwards and around 2000 hardly any meaningful (material) garment production still took place in the Netherlands, apart from small, niche-oriented series (Sanders 2002). An important part of larger-scale garment production in the Netherlands was moved away from major cities long before this time as factory production could easily take place elsewhere in the country where wages were generally lower. Nevertheless, Amsterdam was long able to retain its leading position within the Dutch garment industry, in part thanks to the workshops of Turkish immigrants that employed much informal labor (Raes et al. 2002).

Although the garment industry in Amsterdam still trailed behind its counterparts in The Hague and Utrecht at the turn of the twentieth century, by 1920 the capital city had taken the lead. Afterwards, it never surrendered that position. Jewish tailors fleeing Germany arrived as refugees in Amsterdam in the 1930s and added to the city’s already sizeable multitude of garment producers. Partly due to the expertise that these refugees brought with them, the city remained at the heart of the Dutch garment industry during the postwar period. Ultimately, decline caused by a steadily worsening international competitive position could not be averted. Despite this fact, new immigrant groups provided the impulse for a modest revival during the early 1990s. In the meantime, Amsterdam had already become the center of an emerging Dutch fashion industry that focuses almost exclusively on design (Wenting 2008). It seems likely that the well-developed garment industry Amsterdam spurred the emergence of the local fashion industry, as it did in New York (Rantisi 2004).

It also appears that immigrant groups, especially Jewish and Turkish immigrants, played an important role in fueling the growth of this creative craft sector. This would not be the first time. The diamond cutting industry in Amsterdam, that was world famous before World War II, had been originally set up by Jewish immigrants during the eighteenth century. This industry, which incidentally was by far the most geographically concentrated of all cultural industries in the Netherlands (both in1899 and in 1920 more than 99 % of the approximately 10,000 people employed in the Dutch diamond cutting industry worked in Amsterdam!), remained throughout its history almost exclusively in the hands of the local Jewish community. Sadly, this community was all but wiped out during the Holocaust and the Amsterdam diamond cutting industry was virtually destroyed. At present, a popular museum in Amsterdam devoted to this industry serves as the clearest remaining testimony to the city’s century-long global prominence in the diamond trade that ended with World War II.

7.2 Arts and Crafts

Perhaps the purest form of creative craftsmanship could be found in the arts and crafts sector that focused on the (usually manual) production of elaborately adornments for functional objects, as in copper foil glasswork, calligraphy, lace and engraving. Arts and crafts declined quickly during the first decades of the twentieth century and by 1950 they were no longer considered a separate economic category and had ceased to play a significant role within the Dutch economy. Improved automated production of glasswork, table cloths, toys, small statues, musical instruments, and the like, had undermined these manual crafts. The knowledge and skills of craftsmen in this sector, however, were not completely lost. They evolved to form the basis for, on the one hand, specific styles within the visual arts, and on the other, for the commercial activities that today are known collectively as industrial design. In the same way as the garment industry, therefore, the arts and crafts have produced a strong legacy within the field of cultural production. Nowadays, industrial designers such as Marcel Wanders and Hella Jongerius create aesthetically designed functional objects, just like the craftsmen of the past. The great difference, however, lies in the fact that industrial designers usually create only prototypes while their actual products are mechanically (re)produced. Here as well, design and (re)production have become (spatially) separated. Industrial designers today are often employed by large corporations such as Philips (in Eindhoven) or are active in independent design agencies that constitute part of the creative business services sector.

Around 1900, arts and crafts in the Netherlands depended mainly on local markets and on a relatively well-to-do clientele. As such, they concentrated heavily in the major cities. Rotterdam formed an exception to this rule, perhaps because the city was too strongly oriented towards standardized industrial mass-production. In relative terms, Utrecht displayed the strongest concentration of arts and crafts at this time. This was possibly due to the presence of an archbishop’s seat in the city and a local demand for catholic imagery. Such church patronage, however, proved insufficient for maintaining this local sector in the long run. In The Hague, the arts and crafts also started off from a strong position at the beginning of the twentieth century but were afterwards partly subsumed by the art world proper as art nouveau, which was inspired by the arts and crafts, gained a strong foothold (Cf. Becker 1982). In the visual arts, the ‘The Hague School’, of which Jan Toorop was the most important representative, formed the leading Dutch exponent of this new international art movement. This collection of painters based in The Hague built on both the local arts and crafts scene and the city’s strong position within the Dutch visual arts world (Heij 2004). Amsterdam only became an important center for the Dutch arts and crafts industry during the 1920s when the industry as a whole was already experiencing stagnation and decline in the Netherlands. This temporary upsurge in the country’s capital was probably due to the fact that in 1924 two arts and crafts schools in Amsterdam were combined to form the new Institute for Arts and Crafts Education, that would in later years become the prestigious Gerrit Rietveld AcademyFootnote 1 for art and design (Fig. 15.4).

8 The Arts

The fine arts, meaning the visual arts and literature, together with the performing arts take up a special position within the cultural industries. They are often seen as the ‘creative core’ of the cultural sector, and considered the most experimental and authentic, as well as the least commercially-oriented, of the cultural industries (Pratt 2004; Throsby 2008). This is why the arts have been extensively subsidized by European national governments following World War II and why they take up a central position in Dutch cultural policy. During the postwar heyday of the Dutch welfare state, state subsidies for the arts were distributed through centrally-led national organizations. Only the theater world in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague was supported by local governments rather than by the national state. From the 1980s onwards, when neoliberalism gained momentum, national art policies became largely decentralized and market-driven (Department of Education, Culture and Science 2006). Ever since then, the Dutch art sector has expanded rapidly, where growth in this sector had lagged behind total employment growth between 1930 and 1993. Financial emancipation and commercialization has clearly boosted the arts sector in the Netherlands. The number of persons employed in the arts and art-related activities grew 50 % more rapidly than total employment figures between 1993 and 2005. Despite this recent strong expansion, the arts’ share in national non-agrarian employment was still slightly smaller in 2005 than it had been during the first decades of the twentieth century. Apparently, this cultural industry, which lacks easily reproducible products and is therefore prone to the so-called ‘Baumol’s cost disease’ of relatively stagnant labor productivity (Pratt 2004), profited preciously little from strong postwar growth in mass-consumption and from a standardized national system of subsidies.

The arts’ expansion over the past two decades has been accompanied by a growing role for Amsterdam. The Dutch world of theater, hardly regarded a true art form before World War II, has traditionally centered on Amsterdam, partly due to the presence there of prestigious theaters and music venues. Amsterdam’s domination in this field especially has been retained and strengthened. In general, the arts and related services increasingly agglomerate here. Amsterdam is by far the country’s most important center of the art trade and for museums, although further growth in these fields has lagged behind that in the three other cities since 1993. Especially the Utrecht art scene has slowly started to catch up since then. Rotterdam on the other hand was unable during the entire period under study to establish itself as an arts city and has even lost some ground since 1900. More striking than Rotterdam’s continuous artistic mediocrity, is the strong decline of The Hague’s position within the Dutch art world. The city holds the oldest arts academy in the Netherlands and in 1920 and 1930 The Hague was still the most artistic city of the country. Especially the visual arts flourished there. At the start of the twenty-first century, however, little more than half of this strong degree of arts concentration is left. The art scene in The Hague has not managed to profit from the recent commercialization of the arts sector, perhaps due to a slightly elitist mentality. Nevertheless, the city remains an important arts center and, just as in Amsterdam, artists on average earn more in The Hague than elsewhere in the country (Rengers 2002). Overall, it appears that the arts in particular, the most central core of cultural production, display high degrees of geographical concentration and are bound to specific cities on a long-term basis (Fig. 15.5).

9 Media and Entertainment

The media sector has certain characteristics that distinguish it from other cultural industries and from the arts especially. In the media sector, for example, production and consumption do not necessarily occur simultaneously and within the same venue as is the case with the performing arts. Broadcasters and publishers more easily attain a national or even international market reach so that competition more often takes place on an extra-local level. Not only is their geographical market reach relatively wide, media also cater to all layers of society whereas the arts only rarely manage to do so. This favors a relatively business-like, rather than predominantly artistic attitude. Furthermore, the production processes of media companies often require large-scale investments, and the extensive use of technologies in this sector has made it sensitive to technological changes. These characteristics taken together have assured that in the course of the twentieth century the media sector has grown expansively and has become increasingly concentrated, now largely dominated by a limited number of large organizations on which many smaller specialized firms are dependent.

9.1 Broadcasting

Unlike most cultural industries in the Netherlands, broadcasters have historically been subject to extensive state regulation. After a short period of private experiments, several public radio stations developed around a Philips transmitter factory in the small town of Hilversum during the 1920s. While the first regular radio-broadcasting station in the world was operated by an engineer from a house in The Hague (Scientific Council for Government Policy 2006; see also Van der Groep 2008), the economies of scale created by the Philips-backed factory in Hilversum enabled cost cuts that allowed broadcasting companies there to survive, unlike the station of the pioneer in The Hague that had to discontinue its broadcasts in 1924 for lack of funds. Because of their political significance and the influence of radio and television on public opinion, broadcasters were strictly regulated to conform to a Dutch political system that was strictly ‘pillarized’ (up until the 1960s) and divided according to the different weltanschauungen prevalent in Dutch society. Commercial stations were outlawed until the late 1980s and the state determined that all public broadcasters had to be based in Hilversum so that economies of scale would limit costs. Because of this history, at present 71 % of all people employed in broadcasting in the Netherlands work in Hilversum (Bontje and Sleutjes 2007: 66). The broadcasting industry now employs over 11,000 people and has become exceptionally rooted in a minor city due to (former) conditions of production and a long period of strict regulation.

Ever since government media policies have been liberalized and technological breakthroughs in telecommunication have lowered the costs of broadcasting, Amsterdam has been on the advance in this industry. At the start of the 1990s Amsterdam already possessed many film- and video-production companies as well as many advertising agencies, and these seem to have created a welcoming climate for new broadcasting companies setting up in Amsterdam (Kloosterman 2004). In fact, all four major cities have strengthened their positions in the broadcasting industry over the past 15 years, although Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht have not yet come close to challenging Amsterdam in this regard. The industry appears to be growing especially rapidly in Utrecht, a city in which also the film- and video-production industry is doing well. This confirms the impression engendered by the developments in Amsterdam that these related, but nominally separate cultural industries benefit strongly from each others presence in a city (Fig. 15.6).

9.2 Publishing

The age-old societal position and strength of the publishing industry in the Netherlands precluded the kind of twentieth-century regulation that newer broadcasting media were subject to. Already in the seventeenth century, Amsterdam was one of the hotspots of European book production and a cradle of journalism and the newspaper press. During the twentieth century, the city remained at the heart of the printed word in the Netherlands, although it faced stiff competition from especially The Hague for a long time. The graphic sector, including both publishing and printing companies, grew steadily until the turn of the millennium and more than kept up with general employment growth. Publishers, rather than printers, accounted for more than the lion’s share of this increase. The number of people acting as publishers or working for publishing companies rose from 567 around 1900–37,500 a century later. This amounts to an increase of no less than 6,600 %, which is 12 times as high as the total growth of employment in the Netherlands over the twentieth century. This tremendous growth was mainly the result of skyrocketing demand for published works among a Dutch population that became ever better educated and richer. While the fortunes of publishers rose spectacularly, employment in printing firms stagnated and dropped due to increasing mechanization. A stricter division of labor emerged between publishers and printers. Competition between cities for production of the printed word thus revolved more around the establishment or expansion of publishing companies than around printers. During the first half of the twentieth century, The Hague slightly outperformed Amsterdam in this respect, although Amsterdam always housed more publishers in terms of absolute numbers. The Hague’s prowess in this industry was due in part to the strong concentration of literary authors there and partly due to the city’s publishers of legal works and official state documents. Throughout this time, Amsterdam did remain the unchallenged center of the Dutch newspaper press and of journalism.

In the 1930s, Amsterdam as well as The Hague attracted so-called Exil publishers: Jews and socialists fleeing Nazi Germany. In Amsterdam, this influx contributed to the development of academic publishers and the publishing of international academic books and journals. In the postwar period Amsterdam became a global leader in this field as the company Elsevier became the largest publisher of academic work in the world. Amsterdam publishers also started to outperform their colleagues in The Hague in the fields of fiction and literature, probably responding to the trend that saw authors and poets along with other artists move to Amsterdam (as described above) – although it is difficult to distinguish cause and effect in this case. Amsterdam was also the city where during the second half of the century the country’s most important training facilities for publishers were established (the Frederik Muller Academy, founded in Amsterdam in the 1960s, was even the first academy for publishers in the world) and around the year 2000 some organizations related to the book trade moved their headquarters from The Hague to the capital (Deinema 2008). For these reasons among others, Amsterdam was elected UNESCO World Book Capital for the year 2008 (Fig. 15.7).

10 Creative Business Services

The professionalization of creative business services, by architects, fashion designers and advertising agencies, is mostly a twentieth-century phenomenon. Many of the services rendered by these professions were originally tasks performed by craftsmen or firms that produced the designed or advertised goods and services themselves. It was only over the course of the twentieth century that Dutch firms increasingly turned to external experts to fulfill these functions. Creative business services therefore generally cannot bow on such eminent long histories as some other cultural industries and cannot look back on centuries-long trajectories of development in specific cities, although they may have emerged from older established local industries. Consequently, creative business services achieved tempestuous growth rates with employment for architectural and technical design agencies increasing 20-fold since 1930 while employment in the advertising industry has multiplied by a factor 30 since that same year.

10.1 Architecture

Until several years ago, The Hague possessed the highest concentration of architects in the Netherlands. Amsterdam always trailed behind the court city in this respect and has even experienced a relative slump during the past 15 years. This mediocre performance comes in spite of the fact that the capital city was once a hotbed of architectural creativity; in the 1920s and 1930s ‘Amsterdam School’ architects were heralded internationally as innovators of architecture and urban planning. The architectural sector in The Hague long benefited from a rich and elite local clientele and from commissions for public projects of great prestige such as new national government buildings. Presently, however, The Hague plays a much more modest role within the Dutch architectural scene. Since the 1990s, it has become an international trend that prestigious iconic projects are designed by global ‘starchitects’. This trend robbed architects in The Hague of their formerly privileged position, but has stimulated the exponential growth of a new architecture cluster in Rotterdam containing globally renowned agencies such as Erick van Egeraat, MVRDV and Rem Koolhaas’ OMA.

The growth of the number of architects in Rotterdam, their successes, and the emergence of related activities in the city such as two publishers (NAi and 010) that specialize in books on architecture for a global market, is the result of a fortunate coincidence. At the start of the 1980s, the national government sought to strengthen the city’s cultural infrastructure by establishing the new National Architecture Institute and the (also architecture-related) Berlage Institute there. Almost simultaneously, the Dutch (but England-based) architect Rem Koolhaas, who had become well-known in international architectural circles with the publication of his influential book ‘Delirious New York’ in 1978, moved to Rotterdam in 1981 because he had just received several commissions in the Netherlands and was attracted to Rotterdam’s cheap office space and ‘empty’ cultural environment (Kloosterman 2008). Partly due to Koolhaas, the Dutch architectural scene was reinvigorated and gained a strong international orientation. A local institutional infrastructure of specialized training facilities, funding agencies, meeting places, and publishers, combined with the charisma and international appeal of Koolhaas, spurred the emergence of an internationally competitive architectural cluster in Rotterdam. OMA still functions as an important breeding ground for architectural talent, with young Dutch and foreign designers gaining experience there for several years before starting their own independent agencies, often in Rotterdam (Fig. 15.8).

10.2 Advertising

While architectural design activities in the Netherlands are currently concentrated mainly in Rotterdam, advertising agencies generally prefer Amsterdam as their base of operations. This was already the case in 1930 and remains so today. The advertising industry is 2,5 times as important to Amsterdam’s local labor market as it is on average in the country as a whole. Interestingly, Turkish immigrants have started to enter the advertising industry in Amsterdam and have contributed to its growth and diversity. The capital’s advertising agencies are also held in high international regard and produce global advertising campaigns for large multinational companies. Generally speaking, however, the industry’s focus is still largely confined to the national market and, during the first half of the twentieth century, even revolved mostly around local markets. This explains why Rotterdam and The Hague –together with Amsterdam the most sizeable and well-developed consumer markets in the Netherlands – still accounted for a substantial share of Dutch commercial advertising activity in 1930. Since then the industry has devolved and has become more spread out throughout the country. During the intervening period, consumer markets outside of the four major cities have grown and developed to a great extent. The devolution of an important share of advertising activity away from the major urban center has been further enabled by the increased market reach of advertising agencies that no longer need to be located in the same locality as their main customers, and can now cater to the national market as a whole rather than just to their own local market (Cf. Lambregts et al. 2005; Lambregts 2008). However, the fact that this market reach has expanded has had yet another effect. It made inter-urban competition possible in this industry, allowing Amsterdam’s advertising industry to outcompete its smaller and less-developed counterparts in Rotterdam and The Hague even in their own local markets. Therefore, while the share of the four cities in the industry nationally has decreased, advertising in Amsterdam has become more important relative to that in Rotterdam and The Hague.

The ability of advertisers to reach large audiences, either locally or nationally, is partly dependent on collaborations with the media sector. Indeed, specialists in advertising can hardly do without a strong sense of media-affinity. As Amsterdam has traditionally formed the heart of the national daily press (and has recently attained a fairly strong position in broadcasting and film- and video-production as well) it is not surprising that the capital’s advertising agencies have managed to hold on to their dominant position. The benefits of this relationship have been mutual, as advertisements are an important source of revenue for media-companies. A similar symbiosis has occurred in Utrecht. In that city, the rising fortunes of the advertising industry and of the broadcasting industry have gone hand in hand. Over recent years, both sectors grew in Utrecht to a similar extent (Fig. 15.9).

11 The Four Cities Considered Separately

Although different types of producers in many Dutch cities play a role in the Dutch world of cultural industries, this historical survey has shown that, in the twentieth century at least, this type of activity has been a predominantly metropolitan affair. To the local economies of the major urban regions these industries have proven to be of greater importance than to the country as a whole. This seems to be especially true as this survey has focused almost exclusively on the primary producers of cultural goods and services. Derivative forms of economic activity, such as specialized art shops, employment agencies for designers, and all sorts of suppliers, are probably concentrated in the major cities as well. What has become equally clear is that Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht differ to a significant extent in their ability -both past and present- to sustain specific cultural industries and have them flourish. Apart from specific local environments that nourish particular types of cultural enterprises, the ability of a city to attract talent from afar also appears to be of the utmost importance. While the different industries examined all display their own spatial dynamic, within cities they may also be interconnected. Furthermore, there may be a relation with the city’s attractiveness to a broadly-defined ‘creative class’. Not only artistic types are counted among this class but also a large proportion of the highly-educated population, including academics, managers and lawyers (Florida 2002). It is due to these possible relations with the wider urban context that the four main Dutch cities will each be treated separately now.

11.1 Utrecht

Unfortunately reliable data are not available for all cultural industries in Utrecht, the city that during the twentieth century grew the fastest of the main four in terms of its population and employment figures. The information that has been uncovered points to a difficult trajectory throughout the century, with, for example, a strong decline of the graphic sector and publishing industry. However, at the start of the twenty-first century, Utrecht has attained a strong position in the realms of advertising, architecture, the arts and broadcasting. Some of these reinforce each other through symbiotic connections. And in the case of broadcasting, Utrecht has perhaps profited – in the same way as Amsterdam – from its proximity to Hilversum.

Which conditions have enabled this upward march? Well, to start, Utrecht has finally attained a metropolitan character. Whereas around 1900 the city’s number of inhabitants was less than a fifth of Amsterdam’s (and a third of Rotterdam’s), today Utrecht has grown to almost half of Amsterdam’s size. Perhaps a more important advantage lies in the fact that Utrecht’s university is the largest of the country. Its students refresh the city’s population every year and form a large supply of highly-educated consumers, employees and entrepreneurs. The share of the creative class in the local labor market is higher here than in any other town or city in the Netherlands, and this has been the case since at least 1995 (Marlet and Van Woerkens 2007). These highly-educated inhabitants create greater demand for the arts as well as an atmosphere in which creative endeavors flourish. It cannot be a coincidence that the IT sector in Utrecht is almost as big as that in Amsterdam, twice as big as in Rotterdam, and four times the size of the sector in The Hague.Footnote 2 In an era in which production as well as distribution in cultural industries is increasingly digitized, a strong local specialization in IT can be very useful to a city’s cultural entrepreneurs.

11.2 The Hague

After 1930, and especially during the last decades of the twentieth century, The Hague’s share of Dutch cultural production has gone through an extended period of steady decline. While this city, which houses the royal court and holds the seat of government, formed an important centre for the arts, architecture and the printed word in the past, it seems now to have become a mediocre player in these fields – despite the fact that its publishing scene has exhibited a minor revival over recent years. The city may have a rich tradition in cultural industries, it has lost its grip on this sector. The art world in The Hague has been bled dry partly by Amsterdam’s even greater power of attraction on artists. But one specific weakness in The Hague’s own cultural tradition has rendered it especially vulnerable to stagnation: its cultural producers specialized historically in catering to the elites. In the past the city owed its position as prominent centre for the arts and architecture to the presence of a rich, partly aristocratic, clientele, and to the patronage of the national government.

The Hague’s printers serviced the national government by printing official documents, while its publishers published the country’s jurisprudence. Local architects designed the state buildings and foreign embassies in the city, and the many fine artists in The Hague appealed mainly to distinctly elite tastes. But cultural production aimed mainly at state commissions and a rich upper class has proven partly unsustainable in this case. When the consumption of culture – especially of the written word – became largely democratized after World War II, and the state started to liberalize after 1980, The Hague’s traditions impeded the shift in focus required to take advantage of these developments. The contrast between the traditions of cultural production in The Hague and Amsterdam are telling in this respect. While The Hague has historically produced many prominent painters, such as Jan Toorop, Hendrik Mesdag and Isaac Israels who together formed the ‘The Hague School’, Amsterdam has always been the country’s theatre Mecca. Although the latter cultural form was hardly counted among the arts prior to World War II, it drew larger audiences, and was more strongly bound to specific places and venues than the highly-mobile and lightly-packed visual artists were.

Besides the strong orientation on a (relatively small) elite consumer base, another factor may account for the declining trend that has threatened to eliminate, over the last 20 years especially, The Hague’s prominence in cultural industries. As the sole exception among the four main cities, The Hague lacks a university. It therefore cannot boast a large group of young and highly-educated consumers with a penchant for innovative cultural forms. Despite the cultural heritage of the city, and the fact that The Hague remains the Netherlands’ political centre, the share of the creative class in its population hardly exceeds the national average (Marlet and Van Woerkens 2007). Apparently, this exerts a fairly strong negative influence on The Hague’s cultural industries.

11.3 Rotterdam

Throughout the twentieth century Rotterdam lagged behind when it came to cultural production. It is bound by an industrial character which underrates adornment and the arts, and places a premium on functionality. Nevertheless, Rotterdam’s skyline forms the clearest indication that the city hardly lacks aesthetics or a sense of symbolism. Its lively architectural scene, shows clearly how a local cultural industry may emerge. A combination of physical emptiness (a result of World War II bombing raids on the city), an institutional infrastructure for architectural design that was partly planned and created by the national government, and the fairly incidental arrival of a practitioner of Rem Koolhaas’ prominence, has resulted in an internationally renowned cluster.

It remains to be seen if these successes in the field of architecture will form the prelude to Rotterdam’s advance along a broader cultural front. The architectural profession requires formal training and its designs can only be realized through large pecuniary investments. Barriers to entering the ranks of either producers or (formal) consumers of architecture are therefore quite high, limiting the prospects for easy spillover of the architects’ skills. However, the architects beautify their own city as well which can create strong aesthetic impulses for Rotterdam’s inhabitants. Furthermore, the architectural cluster may expand into several related cultural fields such as interior design, installation art and perhaps computer art as well as the use of digital design programming is widespread among architects.

11.4 Amsterdam

Without any doubt, Amsterdam should be seen as the Netherlands’ cultural capital (Kloosterman 2004; Marlet and Van Woerkens 2004). Direct interaction between specific cultural industries and a general artistic atmosphere has turned the city into a source and catalyst of creativity, as well as a magnet for Dutch and foreign talent. Not only tourists are attracted to the countless cultural amenities in Amsterdam; it has been demonstrated, for example, that the city’s theatre scene has a significant positive effect on Amsterdam’s desirability as place of residence. No other city holds such appeal to people seeking to relocate within the Netherlands. This appeal has naturally led to an expansion of Amsterdam’s already sizeable creative class that is the country’s largest in absolute terms and third largest (After Utrecht and Delft) when considered as a percentage of the total local population (Marlet and Van Woerkens 2007: 14, 232 and 235). Several factors are at the root of this cultural prowess. The specific local trajectories of particular cultural industries have played a role in this respect, but so has the great degree of local tolerance shown historically toward immigrant groups. According to the local press, Amsterdam houses more different nationalities (177) than any other city in the world (Trouw 2007). In the same way that Jews built up Amsterdam’s diamond industry, and Jewish refugees provided new impulses to the city’s clothing and publishing industryFootnote 3 during the 1930s, so can other groups of newcomers play a decisive and innovative role in Amsterdam’s present or future cultural industries.

The industries that are presently flourishing in the country’s capital, did not all develop in the same way, nor did they all arise at the same time. Amsterdam’s fashion design industry, for example, should be seen as a legacy of the old local clothing industry that has all but withered away. The internationally successful academic publishers operating out of Amsterdam have likewise profited from the institutional infrastructures and reputation that they inherited from their seventeenth century predecessors who had made the city into the early-modern ‘bookstore of the world’ (Berkvens-Stevelinck et al. 1992; Deinema 2008). Combined with the impulses delivered by their colleagues who fled to Amsterdam from Nazi Germany, these legacies gave the city’s publishers a strong head start in the newly emerging market for international academic journals. The plethora of visual artists and galleries also attests to the lingering effects of Amsterdam’s early modern position as one of Europe’s main centers for arts and culture. The city’s theatre scene, on the other hand, is more likely to have originated in a similarly enduring aspect of Amsterdam’s distinct traditions and local atmosphere. The same taste for frivolous entertainment that during the second half of the twentieth century produced the infamous Red Light District and coffeeshops that have come to symbolize the city, probably found its expression in the city’s many theatre halls and performance venues during the first half of the century.

Amsterdam’s early lead in the newer advertising industry was probably spurred by the size of its local consumer market, as well as by its well-developed printed media sector. The recent expansion of the broadcasting industry in Amsterdam is strengthened in turn by the city’s advertising agencies. These rising fortunes can also be attributed in part to the concentration of film and video producers in the city that has developed around the national film academy. In general, most cultural industries in Amsterdam continually benefit from the city’s two universities, its vocational colleges, art-related academies (including, among others, an Art and Design Academy, Theater School, Music Conservatory, and Multimedia College), and its many other training and knowledge facilities. Not only do these produce highly-skilled entrepreneurs and specialized labor pools in the city that enhance the industries’ performance, they also serve to attract, retain and create a wide base of local consumers with a general taste for culture.