Abstract

Interest has been growing in recent decades about how governments learn from the experience of others, variously discussed in relation to policy transfer or ‘lesson-drawing’. During the same period, there has also been a substantial increase in the identification and promotion of ‘best practices’ in most areas of policy, including climate change. Underlying these best practices is a frequently encountered assumption that these are effective mechanisms of promoting learning amongst policy-makers and of contributing to improvements and efficiencies of policy-making and practice (Bulkeley, Environ Plan A 38(6):1029–1044, 2006). However, the reality seems to be that best practices, especially examples from afar (and from different contexts), often have only a limited role in policy-making processes: other influences are more important (Wolman and Page, Governance 15(4):477–501, 2002). This paper critically examines the use of best practices in relation to climate change, sustainability and urban policy. It begins by reviewing recent European policy documents, and examines the importance that these documents attach to the identification and dissemination of best practices. Next, the paper identifies some of the main reasons why governments have been increasingly active in developing (or claiming) innovative policies that represent best practice: reasons include image, prestige, power and funding. The paper then reviews literature on how best practices are actually viewed and used by government officials, and examines the extent to which best practices are influential in changing the direction of policy. Information from the four case study cities is then presented and compared against the findings from a similar study carried out by Wolman and Page (Governance 15(4):477–501, 2002), which tried to uncover how local policy officials found out about policy experiences of other local authorities, how they assessed this information, and the extent to which they utilised it in their own decision-making processes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction: The Rise of International Best Practices

The prolonged quest for the best practice in international climate policy has long crowded out serious analysis of what constitutes politically, economically, and managerially viable climate governance at the national or subnational levels. (Rabe 2007: 442)

The concept of best practice (or good practice) is rife in European policies and programmes. In the area of climate change and urban policy, best practices have been developed under a range of international programmes and projects. The underlying belief is often that identifying, promoting and disseminating good practice will help contribute to transnational learning and lead to improvements in policy and practice. This chapter examines this underlying belief. To do so, it considers the validity of international best practices, particularly given the fact that there are huge differences in the technological, economic, political or social situation between countries across the world, and it investigates the function of international best practices in influencing policy-making processes. The paper then outlines some conclusions in the form of directions for future activity in the area of best practice. The paper begins by considering some of the key policies and programmes that promulgate the development or use of best practice in areas related to climate change and urban policy. The main focus of this review is at the European scale, although it is recognised that a range of national as well as international policies and programmes also promulgate the development or use of best practices.

Recent attention to best practice in European policy documents is undeniably high. Frequent mention of best practice can be found in policies such as the 1999 European Spatial Development Perspective, or ESDP (CSD 1999), the 2001 White Paper on European Governance (CEC 2001), the 2005 revised sustainable development strategy (CEC 2005), the 2006 Thematic Strategy on the Urban Environment (CEC 2006), the 2007 Green Paper on Urban Mobility (CEC 2007), the 2007 Leipzig Charter on Sustainable Urban Cities (German Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Affairs 2007b) and the 2007 Territorial Agenda of the European Union (German Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Affairs 2007b). The issue of climate change and urban policy is closely related to the content of many of these documents.

The ESDP’s view on best practice is that ‘the exchange of good practices in sustainable urban policy… offers an interesting approach for applying ESDP policy options’ (CSD 1999: 22). Meanwhile, the 2001 White Paper on European Governance highlights the role of the ‘open method of coordination’ (OMC) as a key factor in improving European governance, which involves activities such as ‘encouraging co-operation, the exchange of best practice and agreeing common targets and guidelines’ (CEC 2001: 21). The 2005 revised sustainable development strategy considers ‘the exchange of best practices’, together with the organisation of events and stakeholder meetings and the dissemination of new ideas, as important ways of mainstreaming sustainable development (CEC 2005: 25). The 2007 Green Paper on Urban Mobility asserts that ‘European towns and cities are all different, but they face similar challenges and are trying to find common solutions’ (CEC 2007: 1) and argues that ‘the exchange of good practice at all levels (local, regional or national)’ (CEC 2007: 5) provides an important way of finding common solutions to these challenges at the European level. The Leipzig Charter on Sustainable Urban Cities (German Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Affairs 2007a: 7) calls for ‘a European platform to pool and develop best practice, statistics, benchmarking studies, evaluations, peer reviews and other urban research to support actors involved in urban development.’ The Territorial Agenda of the European Union (EU) contains a whole annex of examples of ‘best practices of territorial cooperation’ (German Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Affairs 2007b).

The EU’s 2006 Thematic Strategy on the Urban Environment (CEC 2006) has perhaps the most to say about best practices concerning climate change and urban development. In fact, the exchange of best practices forms one of the four main actions of the strategy. The strategy states that ‘many solutions already exist in certain cities but are not sufficiently disseminated or implemented’ and that ‘the EU can best support Member States and local authorities by promoting Europe’s best practices, facilitating their widespread use throughout Europe and encouraging effective networking and exchange of experiences between cities’ (CEC 2006: 3). The document argues that ‘improving local authorities’ access to existing solutions is important to allow them to learn from each other and develop solutions adapted to their specific situation’ and highlights that ‘the Commission will offer support for the exchange of good practice and for demonstration projects on urban issues for local and regional authorities’ (CEC 2006: 6).

Examples of best practice in European research programmes and cooperation initiatives are widespread. Examples include programmes funded under the European Regional Development Fund (e.g. INTERACT, ETC./INTERREG, URBACT), pre-accession funding programmes (e.g. IPA—the successor of Phare, ISPA and SAPARD), research programmes, environmental programmes (e.g. LIFE+) and rural development programmes (e.g. LEADER+, which ran from 2000 to 2006). The European Research Framework Programme (and particularly the Energy, Environment and Sustainable Development thematic programme of the Fifth Framework Programme—EESD) have given rise to a number of projects that have developed best practice guides/comparisons (see Stead 2012). The extent to which these projects have considered the applicability of best practices in another context and the transferability of these examples, especially to different parts of the EU, has, however, been rather limited. Much more attention has been focused on identifying and assembling examples of best practice rather than considering how best practice examples might be useful in influencing policy-making in other situations (Stead 2012).

Attention to best practice at the global level is also high. Publications on best practices can, for example, be found within the OECD and the World Bank. These include the OECD report ‘Best Practices in Local Development’ (OECD 2001) and the World Bank working paper entitled ‘Local Economic Development: Good Practice from the European Union (and beyond)’ (World Bank 2000). In addition, the UN-Habitat supports the Best Practices and Local Leadership Programme, ‘dedicated to the identification and exchange of successful solutions for sustainable development’ (UN-Habitat 2008) and aims to ‘raise awareness of decision-makers on critical social, economic and environmental issues and to better inform them of the practical means and policy options for improving the living environment… by identifying, disseminating and applying lessons learned from best practices to ongoing training, leadership and policy development activities’ (UN-Habitat 2008). Best practices are central to the 2010 OECD publication on Cities and Climate Change, which it claims was developed ‘for countries to discuss and develop a shared understanding of good practice on climate policy issues’ (OECD 2010: 3; emphasis added) with the objective of enhancing ‘the ability to identify and diffuse best practices’ (op cit.: 28).

These various European and global policies, programmes and initiatives are indicative of ‘softer’ forms of policy steering (based on voluntary cooperation), and all serve to illustrate that the development and dissemination of best practice is widely considered to be an effective means of promoting policy transfer and learning. According to Bulkeley (2006: 1030), the assumption that the dissemination of best practice can lead to policy change ‘has become an accepted wisdom within national policies and programmes, as well as in international arenas and networks.’ The logic seems to be that, by providing information or knowledge about specific initiatives, other individuals and/or organisations will be able to undertake similar projects or processes, or learn from the experience, which will lead to policy change (Bulkeley 2006: 1030). However, despite the attention on best practice in policies, programmes and projects, little is known about the ways in which best practices are produced and used, and their function in processes of policy-making. This chapter seeks to explore these issues in more detail.

2 The Validity of Best Practices

What becomes known as best practice may, in reality, be the manifestation of the best advertising and most effective programmatic or municipal spin doctoring. The danger is that falling for perception rather than reality can lead cities or states to adopt policies that might not work or to look for ways policies have been implemented where the implementation failed. (Wolman et al. 2004: 992)

A common assumption behind best practices is that they are equally applicable and effective in another setting. However, the large number and diversity of European Member States, where there are substantial differences in governance, administrative cultures and professional capacities, make such an assumption questionable. This assumption is particularly questionable in the case of transposing best practices between dissimilar countries, such as from Western to Eastern Europe (‘old’ to ‘new’ Member States of the EU), where the social and economic situation, as well as the institutional frameworks, are often very different in the ‘borrowing’ and ‘lending’ countries. Nevertheless, examples can certainly be found where countries in Eastern Europe have used best practices from Western Europe as a way of trying to catch up politically and/or economically (Rose 1993). Randma-Liiv (2005: 472) states that ‘policy transfer has become a fact of everyday life in various countries’ and that ‘post-communist countries have been especially willing to emulate the West’.

Various factors, including European initiatives for research, territorial cooperation and development assistance (see above), have inspired these processes of policy transfer from Western to Eastern Europe. Politicians often see policy transfer as the quickest solution to many problems without having to reinvent the wheel (Rose 2005; Tavits 2003). In Eastern Europe, policy transfer is frequently regarded as a means of avoiding newcomer costs: using the experience of other countries is cheaper because they have already borne the costs of policy planning and analysis, whereas creating original policies requires substantial financial resources (Randma-Liiv 2005). The availability of financial resources to support these processes of west-east policy transfer is, of course, another (and perhaps the most important) factor behind these processes taking place, especially where funding from other levels is limited. However, as the OECD report ‘Best Practices in Local Development’ recognises, best practice is not without its complexities and challenges because ‘the possibilities of what can be achieved by policy may vary between different areas and different times’ and because there is ‘no single model of how to implement local development or of what strategies or actions to adopt’ (OECD 2001: 29).

There are also limitations of best practice in terms of the ability to transfer sufficient detailed knowledge and information in the form of case study reports, policy documents, policy guidance notes or databases. In effect, best practice seeks to make the contextual, or tacit, knowledge about a process or instrument explicit by means of codification (Bulkeley 2006). However, this process is not as straightforward as the production of best practices might make it seem because ‘expressing tacit knowledge in formal language is often clumsy and imprecisely articulated’ (Hartley and Allison 2002: 105). Accounts of best practices are often condensed and sanitised, and lacking in detail for application elsewhere. In the words of Vettoretto (2009), ‘good practice [or best practice] is cleansed of the political dimension of policy-making and of the historically defined local social and cultural differences’ (Vettoretto 2009) and the production of ‘repertoires of good practices is usually associated with some degree of de-politicization and de-contextualization’ (Vettoretto 2009). Wolman et al. (1994) make a similar point in relation to the difficulty in conveying the full picture of best practice. They report that ‘delegations from distressed cities are frequent visitors to … ‘successful’ cities, hoping to learn from them and to emulate their success’ but ‘these visitors—and others who herald these ‘urban success stories’—are frequently quite unclear about the nature of these successes and the benefits they produce’ (Wolman et al. 1994: 835). Clearly, the less detailed an example of best practice is (and the more sanitised the account of its design or implementation), the less likely it will be that the example can be replicated elsewhere.

In terms of the transferability of best practice, the OECD report on Best Practices in Local Development (OECD 2001) differentiates between various components of best practice and identifies the extent to which each of these can be transferred (Table 1). At one end of the spectrum of components are ideas, principles and philosophies which are considered to have low visibility (since they can be difficult for the outside to fully understand and specify) and are difficult to transfer because it can be difficult to make them relevant to other situations. At the other end of the spectrum are programmes, institutions, modes of organisation and practitioners which tend to have high visibility and are relatively easy to understand, but are not very transferable since they tend to be specific to particular areas or contexts. According to the OECD report, it is components, such as methods, techniques, know-how and operating rules, with medium visibility that make the most sense to exchange or transfer. Contrary to the OECD’s classification, however, it could also be argued that policy ideas and principles may in fact be some of the most transferable components of exchange in relation to policy transfer processes.Footnote 1

The OECD report on Best Practices in Local Development also highlights the need to examine who is involved in the process of transfer in order to gauge transferability of best practices. It distinguishes between top-down transfer processes initiated by promoters (e.g. national agencies) seeking to disseminate best practices and bottom-up processes initiated by ‘recipients’ in response to a need that they have recognised themselves. It argues that the latter is likely to work best. This is very much linked to the notions of demand-led and supply-led processes of policy transfer: demand-based policy transfer is based on the initiative and acknowledged need of a recipient administration, whilst supply-led policy transfer is based on the initiative of the donor and the donor’s perception of the needs of the recipient, such as foreign aid initiatives (Randma-Liiv 2005).

Urban policy officials are now routinely involved in transboundary cooperation networks and inter-regional collaboration initiatives, and thus subject to foreign experiences and exposed to a variety of policy approaches from other Member States (Dühr et al. 2007). Nevertheless, literature on the Europeanisation of spatial planning suggests that different policy concepts take root in different ways across the European territory (see, for example, Böhme and Waterhout 2007; Dabinett and Richardson 2005; Giannakourou 2005; Janin Rivolin and Faludi 2005; Tewdwr-Jones and Williams 2001), which means that it is unlikely that best practices will lead to the same outcomes across different European Member States, no matter how faithfully transferred.

Wolman et al. (2004) take a very critical view about how best practices are identified, arguing that best practice in urban public policy is frequently built around perceptions without much evaluation. They argue that both receivers and producers of best practices have virtually no means of assessing the validity of the information they receive, and that most do not even recognise this as a problem. They also contend that identifying best practice is often ‘an exercise in informal polling’ (Wolman et al. 2004:992) and argue that the reputations of so-called best practice simply snowball as observers become self-referential. This is very much related to observations by Benz (2007), who argues that sub-national governments in Germany are becoming increasingly active in developing (or claiming) innovative policies, which they then try to sell as ‘success stories’ and best practices. According to Lidström (2007: 505), ‘in this new competitive world of territorial governance, most units depict themselves as winners.’ To be highly ranked and used as a benchmark is not only a good image for the locality, it can also attract additional money from the federal government. It is equally likely that this is also the case in other countries and also at the EU level, with sub-national governments competing for EU funding by promoting ‘success stories’ and best practices. In so doing, they not only attract additional national and regional funding, they can also use EU funding to partly bypass traditional structures of domestic policy-making and vertical power relations, should they so wish (Carmichael 2005; Heinelt and Niederhafner 2008; Le Galès 2002).

The creation and use of best practices as a means of reward and recognition for particular initiatives, individuals and places means that it is often only the ‘good news’ stories that are disseminated, and that the sometimes murky details of how practices were put into place (and any difficulties or failures along the way) are obscured. This means that examples of unsuccessful practices rarely come to light in the same way as examples of ‘success’, despite the fact that negative lessons might be equally important to policy officials in learning about policies or practices that may not work and the reasons why (Rose 2005). Aware that best practices represent sanitised stories, practitioners often pursue their own networks of knowledge in order to gain an understanding of the processes involved (Bulkeley 2006).

3 The Function of Best Practices

To what extent are… policy instruments, which have proved to be successful in one urban area, transferable to another, given that the latter has a different historical, cultural or political background, or is in another phase of economic development? Are there ‘best practices’ which are convertible like currencies? If not, how and to what extent must one take account of specific circumstances? (Güller 1996: 25)

Despite the proliferation of best practice examples, academic literature suggests that the practical use and usefulness of best practices may in fact be rather limited. While a high proportion of local authority actors agree that learning from the experience of others is important and indicate that they engage in such activity, only a small minority of officials believe that it plays a large or significant role in their decision-making (Wolman and Page 2002). In a study of urban regeneration policy, it is reported that officials generally find government documents and conversations with other officials more useful for finding out what is going on than from good practice guides (Fig. 1). The results also suggest that the majority of officials believe that information about other examples from the same country may have some effect on decisions within their own authority, although few think that the effects will be ‘significant’ or ‘large’ (Table 2). However, when questioned about the effect of examples from abroad on decisions within their own authority, most officials believe that the effects of these examples will be either ‘little’ or ‘none’. Informal contacts with peers are reported to be the most trusted and useful sources of information among local government officials, while mechanisms such as seminars, conferences and good-practice guides are less useful. It is argued that one of the most important reasons for looking at examples from elsewhere is to gain information about what kind of proposals the government is likely to fund, rather than using best practices as inspiration for new policy or practice.

Relative frequency of use and usefulness of different sources of information for policy-making (figures constructed using data from Wolman and Page 2002: 485). a Frequency of use of information from different sources. b Usefulness of information from different sources

This data leads Wolman and Page (2002) to conclude that, despite the enormous effort that has been devoted to disseminating ‘good practice’, their findings throw cold water over activities concerning the identification and dissemination of best practice, at least in the area of urban regeneration. They acknowledge that the same is not necessarily true for other areas of policy, although there seems little reason to think that the situation may be much different in the area of climate change and urban policy. They also conclude that, even when well resourced and pursued actively, the effects of spreading lessons and ‘good practice’ are not very well understood by those involved in the processes of dissemination and that this observation is unlikely to be unique to the area of urban regeneration alone. Similarly, Bulkeley (2006) concludes that the impacts and implications of disseminating best practice on urban sustainability remain poorly understood.

3.1 Evidence from Four Case Study Cities

Some of the observations about the use and usefulness of best practices reported above have recently been tested as part of the EU-funded SUME project (Sustainable Urban Metabolism in Europe) in the area of sustainable urban development policy. Although the sample size is relatively small, the results help to confirm that Wolman & Page’s findings from 2002 in the area of urban regeneration policy are more widely applicable (in this case to urban planning policy) and that their findings still generally hold true almost a decade later.

The relative use and usefulness of best practices were tested among a number of policy officials in four case study cities: Newcastle upon Tyne, Porto, Stockholm and Vienna. Information was gathered by means of questionnaires (in combination with workshops and interviews in some cases). While all four city regions are relatively similar in terms of area and population size (between 1 and 2 million inhabitants), the cities neatly illustrate a variety of different policy contexts. Each of the four case studies belongs to a distinct legal and administrative family and each of the countries where the four case studies are located have quite separate spatial planning traditions (CEC 1997), ‘models of society’ and welfare systems (Nadin and Stead 2008). These wide contextual differences between case studies offer the opportunity to test opinions and approaches concerning best practices across a broad range of institutional conditions.

Policy officials in the four case study cities were asked about their opinion on the extent to which policies and practice are influenced by examples elsewhere. Several questions were developed from an earlier study by Wolman & Page (see above) who investigated how local authority officials involved in urban regeneration policy learn from each other’s experience.

Looking first at local influences on policy-making in the case study cities, a wide variation in opinions is apparent regarding the influence of practices in surrounding local authorities on policy decisions in the case study cities. Opinions greatly differ not only between case study cities but also between officials in the same city. For some officials, decisions in nearby local authorities rarely influence decision-making in their own authority, while others believe that decisions in nearby local authorities frequently influence decision-making in their own authority. On average, decisions in nearby local authorities are considered to influence decision-making occasionally in the case study cities.

In terms of national influences on policy-making in the case study cities, a wide variation in opinions is again apparent between the cities and also between officials within the same city. In general, national examples are considered to be more important than international examples (see below). Examples from other local authorities in the same country are generally considered to have a moderate effect on shaping planning policies and practices in the case study cities (in line with the results of Wolman & Page’s study—see above).

A wide variation in opinions is again apparent concerning international influences on policy-making in the case study cities. However, opinions on this issue mainly differ between case study cities rather than between officials in the same city. International examples are generally considered to have only a small effect on planning policies and practices in the case study cities (also in line with the results of Wolman & Page’s study). When officials make use of international examples, they mainly look to practice elsewhere in Europe rather than further afield. However, one respondent makes the point that, while international examples often have minimal direct effect, they can also have a more indirect effect. They can, for example, influence European guidelines and directives, which may then be translated into national law and policy, which in turn can have impacts for planning policies and practice.

The number of responses obtained from the case study cities is too low to make detailed quantitative comparisons. Nevertheless, some important conclusions can be drawn from the responses from the policy officials in the case study cities. In the case study cities, policy officials consider the most useful sources of information to be other policy officials, presentations at seminars and conferences and electronic information. In terms of frequency of use, conversations with officials, good practice guides and presentations at seminars and conferences score highly. On the other hand, academic journals and conversations with councillors are neither used frequently to inform policy-making nor are they considered to have much influence on policy. These observations from the case study cities are broadly in line with the results of the study by Wolman and Page (2002). One notable difference, however, is the frequency of use and level of importance attached to electronic information. As might be expected, given the fact that the research carried out by Wolman & Page took place more than a decade earlier (interviews were carried out in 1999 and 2000), the importance of electronic information was significantly lower for Wolman & Page’s interviewees than for the policy officials interviewed in the four case study cities (in 2011). While government publications were considered to be one of the most regular and useful sources of information in Wolman & Page’s study, they were considered less important, relative to other sources, by the policy officials interviewed in the four SUME case study cities, especially in Austria. This may be related to the federal system of government in Austria and the fact that central government is less involved in spatial planning issues, or it may simply be a more general reflection of the streamlining of planning regulations across all the case studies (and most of Europe), where fewer national government documents are being produced to guide and support policy-making at the local level.

4 Conclusions: The Need for a Reappraisal of Best Practice

The previous two sections of this paper have identified a number of issues and concerns related to the validity and function of best practice. In terms of validity, there are concerns about issues of transferability, especially between dissimilar situations (e.g. ‘old’ to ‘new’ Member States of the EU), the lack of detail that best practices are able to convey (and the fact that some are sanitised, good news stories without details of problems, difficulties or failures along the way), the lack of evaluation of many examples of best practice and a certain degree of distrust or scepticism in best practices on the part of practitioners. In practice, transfers of best practices are complex and certainly not merely a matter of copying or emulation: successful transfer also involves processes of learning and adaptation. Substantial differences in political and administrative cultures across Europe, to name just two factors, reduce the relevance and impede the applicability of best practices and their transfer. According to Wolman and Page (2002: 498), it is ‘much easier to offer a compendium of practices and ideas and leave it up to the recipient to decide which is the most appealing than to offer an evaluation of what works best, let alone what works best for highly differentiated audiences.’

In terms of the function of best practice, there are concerns about the proliferation of examples and the overload of information for policy officials, the low level of impact that these examples often have, especially in the case of international examples (compared to examples from the same country) and the lack of a wide and systematic assessment of the impacts and implications of disseminating best practice on policy-making. In many cases, the identification or use of best practices has more of a symbolic rather than functional purpose, and these best practices are generally not very central to policy-making processes. Given these issues and concerns, a reappraisal of the status and use of best practice seems to be necessary.

First, it is time to reappraise the importance attached to best practice in policies, programmes and projects, particularly at the European level. There are substantial social, economic and institutional differences between EU Member States, but there is little recognition of the fact that policy options need to be differentiated: the underlying assumption of many European policies and programmes is that best practices are equally applicable and effective in another setting. A more detailed study of the way in which best practice examples of climate change and urban planning are used across Europe (building, for example, on the work of Wolman and Page 2002) would be instructive and would help to inform the way in which best practice examples are used in European policies and programmes.

Second, it is time to reappraise the way in which best practice examples are presented and to consider whether it would be better to differentiate between various components of best practice according to the extent to which these can be transferred (see also Table 2 above). Because of the diversity of Member States, institutions, planning instruments and cultures across Europe, it is perhaps more appropriate to consider a move away from the idea of best practice examples and refer instead simply to examples of practice, which policy officials can draw on and adapt to their own circumstances (as advocated in OECD 2001).

Third, there is substantial merit in carrying out more detailed examinations of the transferability of urban planning methods, techniques, operating rules, instruments, programmes, and so on. Detailed, systematic work is lacking in this area and research in this area would provide an interesting contribution to debates in both academia and in practice. Related to this, research on the processes of transfer of planning methods, techniques, operating rules, instruments, programmes, and so on, would be very instructive, particularly in cases where examples have been transferred between dissimilar situations (e.g. between ‘old’ to ‘new’ Member States of the EU). Such research could include theories and concepts from the policy transfer (and related) literature as well as literature on planning cultures (Sanyal 2005), social or welfare models (Nadin and Stead 2008) and path-dependency/path-shaping (Dabrowski 2010; Kazepov 2004).

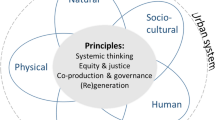

Finally, one further direction for future work related to the area of best practice might be to examine and test the extent to which there are common principles (as opposed to best practices) across different contexts (e.g. scales and systems of governance). This could, for example, build on the 2010 OECD report on Cities and Climate Change, which identifies a set of principles for strengthening the multi-level governance of climate change (Table 3), and/or the 2008 UNECE report on spatial planning, which is premised on the idea that certain principles (democracy, subsidiarity, participation, policy integration, proportionality and the precautionary approach) are applicable and desirable for all planning systems, irrespective of differences, such as the economic and social situation, planning cultures and social or welfare models (UNECE 2008).

Notes

- 1.

The view that policy ideas and principles may be some of the most transferable components of policy is also reflected in the 2008 UNECE report on spatial planning, which is premised on the idea that, while spatial practices may substantially differ between countries, there are core principles of spatial planning that apply in all cases (UNECE 2008) and, to some degree, in the 2010 OECD report on Cities and Climate Change, which proposes a set of principles for strengthening the multi-level governance of climate change (OECD 2010).

References

Benz, A. (2007). Inter-regional competition in co-operative federalism: new modes of multi-level governance in Germany. Regional & Federal Studies, 17(4), 421–436.

Böhme, K., & Waterhout, B. (2007). The Europeanization of planning. In A. Carbonell & A. Faludi (Eds.), Gathering the evidence—The way forward for European planning? (pp. 1–27). Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Bulkeley, H. (2006). Urban sustainability: learning from best practice? Environment and planning A, 38(6), 1029–1044.

Carmichael, L. (2005). Cities in the multi-level governance of the European Union. In: M., Haus, H., Heinelt & M., Stewart (Eds.), Urban governance and democracy: Leadership and community involvement (pp. 129–148). London: Routledge.

Commission of the European Communities—CEC. (1997). The EU compendium of spatial planning systems and policies. Regional development studies. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Commission of the European Communities—CEC. (2001). European governance. A white paper. COM(2001)428 final. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Commission of the European Communities—CEC. (2005). Communication from the commission to the council and the European Parliament on the review of the sustainable development strategy. A platform for action. COM(2005)658 final. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Commission of the European Communities—CEC (2006). Communication from the commission to the council and the European Parliament on thematic strategy on the urban environment. COM(2005)718 final. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Commission of the European Communities—CEC (2007). Green Paper. Towards a new culture for urban mobility COM(2007)551 final. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Committee on Spatial Development—CSD (1999). European spatial development perspective: towards balanced and sustainable development of the territory of the EU. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Community.

Dabinett, G., & Richardson, T. (2005). The europeanisation of spatial strategy: Shaping regions and spatial justice through governmental ideas. International Planning Studies, 10(3/4), 201–218.

Dabrowski, M. (2010). Technocratic networks, path dependency and institutional change: Civic engagement and the implementation of the structural funds in Poland. In N. Adams, G. Cotella, & R. Nunes (Eds.), Territorial development, cohesion and spatial planning: Building on EU enlargement (pp. 205–228). London: Routledge.

Dühr, S., Stead, D., & Zonneveld, W. (2007). The Europeanization of spatial planning through territorial cooperation. Planning Practice and Research, 22(3), 291–307.

German Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Affairs. (2007a). Leipzig charter on sustainable european cities. Agreed at the occasion of the informal ministerial meeting on urban development and territorial cohesion on 24–25 May 2007. Retrieved from www.bmvbs.de/SharedDocs/EN/Artikel/SW/leipzig-charter-on-sustainable-european-cities.html [Accessed: 22 June 2011].

German Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Affairs (2007b). Territorial Agenda of the European Union: Towards a More Competitive and Sustainable Europe of Diverse Regions. Agreed at the occasion of the Informal Ministerial Meeting on Urban Development and Territorial Cohesion on 24–25 May 2007. Retrieved from: www.bmvbs.de/territorial-agenda [Accessed: June 22 2011].

Giannakourou, G. (2005). Transforming spatial planning policy in mediterranean countries: europeanization and domestic change. European Planning Studies, 13(2), 319–331.

Güller, P. (1996). Urban travel in east and west: key problems and a framework for action. In: ECMT (Ed.), Sustainable transport in central and eastern european cities (pp. 16–43). Paris: ECMT.

Hartley, J., & Allison, M. (2002). Good, better, best? Inter-organizational learning in a network of local authorities. Public Management Review, 4(1), 101–118.

Heinelt, H., & Niederhafner, S. (2008). Cities and organized interest intermediation in the EU multi-level system. European Urban and Regional Studies, 15(2), 173–187.

Janin Rivolin, U., & Faludi, A. (2005). The hidden face of european spatial planning: Innovations in governance. European Planning Studies, 13(2), 195–215.

Kazepov, Y. (2004). Cities of Europe: Changing contexts, local arrangements, and the challenge to social cohesion. Oxford: Blackwell.

Le Galès, P. (2002). European cities. Social conflicts and governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lidström, A. (2007). Territorial governance in transition. Regional & Federal Studies, 17(4), 499–508.

Nadin, V., & Stead, D. (2008). European spatial planning systems, social models and learning. disP, 172(1), 35–47.

OECD. (2001). Best practices in local development. Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2010). Cities and climate change. Paris: OECD.

Rabe, B. G. (2007). Beyond kyoto: Climate change policy in multilevel governance systems. Governance, 20(3), 423–444.

Randma-Liiv, T. (2005). Demand- and supply-based policy transfer in estonian public administration. Journal of Baltic Studies, 36(4), 467–487.

Rose, R. (1993). Lesson-drawing in public policy: A guide to learning across time and space. New Jersey: Chatham House.

Rose, R. (2005). Learning from comparative public policy: A practical guide. London: Routledge.

Sanyal, B. (Ed.). (2005). Comparative planning cultures. Londonk: Routledge.

Stead, D. (2012). Best practices and policy transfer in spatial planning. Planning Practice and Research 27(1), 103–116.

Tavits, M. (2003). Policy learning and uncertainty: The case of pension reform in Estonia and Latvia. Policy Studies Journal, 31(4), 643–660.

Tewdwr-Jones, M., & Williams, R. H. (2001). The European dimension of British planning. London: Spon.

UN-Habitat. (2008). Best practices and local leadership programme. Nairobi: UN-Habitat. Retrieved from www.unhabitat.org/categories.asp?catid=34 [Accessed: June 22 2011].

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe—UNECE. (2008). Spatial planning. Key instrument for development and effective governance with special reference to countries in transition. Economic Commission for Europe Report ECE/HBP/146. UNECE: Geneva.

Vettoretto, L. (2009). A preliminary critique of the best and good practices approach in european spatial planning and policy-making. European Planning Studies, 17(7), 1067–1083.

Wolman, H., & Page, E. (2002). Policy transfer among local governments. An information theory approach. Governance, 15(4), 477–501.

Wolman, H., Hill, E. W., & Furdell, K. (2004). Evaluating the success of urban success stories: Is reputation a guide to best practice? Housing Policy Debate, 15(4), 965–997.

Wolman, H. L., Ford, C. C., & Hill, E. W. (1994). Evaluating the success of urban success stories. Urban Studies, 31(6), 835–850.

World Bank. (2000). Local economic development: Good practice from the European Union (and beyond). Urban Development Unit unpublished paper. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

Acknowledgments

This chapter is partly based on work carried out for the SUME research project (Sustainable Urban Metabolism in Europe), grant agreement number 212034, funded under the Environment theme of the EC Seventh Framework Programme (FP7-ENVIRONMENT-2007-1). The author is grateful to the other partners in the project who helped to collect information from policy officials in the four case study cities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Stead, D. (2013). Climate Change, Sustainability and Urban Policy: Examining the Validity and Function of Best Practices. In: Knieling, J., Leal Filho, W. (eds) Climate Change Governance. Climate Change Management. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-29831-8_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-29831-8_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-29830-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-29831-8

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsEconomics and Finance (R0)