Abstract

In the second chapter, Helm and Klode describe the “Challenges in Measuring Corporate Reputation” which most communication professionals should be aware of when selecting a measurement tool. The authors expand on the pros and cons of single versus multiple-item measurement concepts, discuss formative versus reflective models, and evaluate the benefits of low and higher order factors. In a second part, Helm and Klode introduce common measurement tools used both by practitioners and in academia and discuss the need for nonstandardized tools.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Measurement Model

- Stakeholder Group

- Corporate Reputation

- High Order Factor

- Structural Equation Modeling Model

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

“One thing that we have learnt from the discipline of marketing is that the most dangerous place to look at stakeholders is from behind a desk. The simple truth of the matter is that the only way accurately to gauge what people think of an organization is to ask them. This is easy to say, but often difficult to do” (Dowling 2001).

Most researchers and practitioners in the field of reputation management will agree that “to be managed, corporate reputations must be measured” (Gardberg and Fombrun 2002), preferably by taking into account the target group of reputation management: the stakeholders of the firm. While awareness for the need of measurement prevails, there is by far no consensus on how to measure: “The biggest hurdle in making the case for building, maintaining and managing reputation is how to measure it effectively” (Larkin 2003).

Within the resource-based view of the firm, corporate reputation is interpreted as an intangible asset offering sustainable competitive advantage due to its valuable, rare, inimitable, and nonsubstitutable nature (Barney 1991). Reputation is an “umbrella” construct, capturing cumulative impressions of internal and external stakeholders beneath its “shield” (Chun 2005; Caruana and Chircop 2000). The ingredients of reputation are all salient characteristics of a firm while reputation itself – conceived as a hypothetical construct – is neither directly observable nor measurable (Caruana and Chircop 2000; Rossiter 2002). Individuals are the source of information about a firm’s reputation. As Wartick (2002) clarifies: “reputation, be it corporate or otherwise, cannot be argued to be anything but purely perceptual.” Hence, the objects of empirical research are perceptions of the reputation of an entity.

Perceived corporate reputation can be understood as an individual’s impression of a firm, and this individual perception of reputation is based on a “collective assessment of the company’s ability to provide valued outcomes to a representative group of stakeholders” (Fombrun et al. 2000) meaning that the individual takes into account what he thinks a collective (e.g., “the public”; “the stakeholders”) think about the company. In the context of this chapter, the term “corporate reputation” is defined as the individual’s estimation of an assumed aggregated perception of all stakeholders towards all salient characteristics of a firm (Barnett et al. 2006). Perceived reputation has to be distinguished from similar constructs such as identity and image: “identity captures who the organization is and what it does, image captures the message the organization sends outward about who it is and what it does, and reputation captures what others think about who the organization is and what it does” (Lewellyn 2002). Reputation as an indirectly perceived construct – individuals’ perceptions refer to other stakeholders’ perceptions of a firm – appears to be more complex than corporate identity or corporate image (van Riel et al. 1998). Measuring an individual’s attitude like identity or image is not equivalent to measuring an individual’s opinion of other people’s impressions, perceptions, or attitudes (Dowling 2001). Consequently, the degrees of freedom of choosing a fitting measurement approach must be higher than those for relatively more concrete constructs such as corporate identity or corporate image (Barnett et al. 2006). In order to discuss challenges of reputation measurement, we focus on the following aspects which also determine the structure of the chapter.

We have clarified the objects of reputation measurement by our definition of reputation; we will further outline schools of thought in reputation measurement. In the section on building measurement models, we will discuss the pros and cons of single versus multi item measures of reputation and then turn to model configurations. Specifically, we will elaborate on the epistemic nature of measurement models (formative versus reflective), their anchorage in nomological networks, and the dimensionality of constructs (lower and higher order factors). In the fourth section, we will outline two standardized measures for reputation often referred to in the literature and, in a further section, turn to the issue of whether a standardization or adaptation of measures to specific stakeholder groups is mandatory. A short summary concludes the chapter.

Schools of Thought in Reputation Measurement

Apart from the challenges encountered when defining reputation, various approaches to its operationalization and conceptualization in a measurement context can be discerned. Berens and van Riel (2004) identify three main streams of measurement of corporate associations which relate to relationships between firms and their stakeholders (1) social expectations, (2) corporate personality, and (3) trust. In their meta-analysis of 75 studies conducted between 1958 and 2004, nearly 60% pertain to one of these three main streams of thought with the measurement of social expectations as their most common one. Social expectations are viewed from the stakeholder’s perspective and concentrate on the manner in which reputation is formed (Fombrun and van Riel 1997).

Another meta-analysis of 22 key studies conducted by Chun (2005) detects three schools of thought, namely the evaluative, the impressional, and the relational schools which closely resemble Berens’ and van Riel’s (2004) classification. The evaluative school measure reputation by the assessment of the firm’s achievements which can be viewed as confirmed social expectations (e.g., commitment to charitable and social issues, value for money of products, or financial performance; Helm 2005). The impressional school comprehends reputation as the overall impression of a corporation and tries to capture the organization’s personality with different facets like, e.g., elegance, empathy, or dominance (Davies et al. 2001). The relational school wants to reveal differences between internal and external views in order to reduce gaps or deficits and incorporate measures related to trust as, for instance, honesty, expertise, or trustworthiness within different stakeholder groups (Newell and Goldsmith 2001; Helm 2007c).

Building Measurement Models for Corporate Reputation

Reputation is usually operationalized as a judgmental perception leading to either a positive or negative evaluation of the firm’s reputation (Dollinger et al. 1997). As a consequence, an evaluation of corporate reputation has to result in certain values on a metric scale between the binary counterpoints “good reputation” or “bad reputation.” An assessment of studies measuring corporate reputation revealed that the majority applied measurement scales where the evaluation of a reputational indicator is a specific value on a Likert scale (van Riel et al. 1998).

Measurements of reputation can be based on single- or multi-item approaches. Figure 1 depicts the two modes of capturing reputation and their effects on assumed economic consequences.

Bergkvist and Rossiter (2007) proved in a recent study that multi- and single-item measures do not lead to significant differences in predictive validity. A single-item measure can possess nearly perfect correlation with a multi-item measure (Bergkvist and Rossiter 2007). In addition, it meets practitioner needs to reduce data collection complexity (Fombrun 2007). Yet, Helm (2005) states that using a single-item measure “does not lead to practical insights for reputation management because the source of a good or bad reputation does not become evident.” Single-item measures are considered unsuitable to seize the numerous salient characteristics of a firm (Caruana and Chircop 2000). From a methodological viewpoint, using both – a single-item measure and a multi-item measure within one model – allows adding a similar entity to the reputation constructFootnote 1 and furthermore the possibility to test nomological validity of the multi-item measure (Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer 2001).

An example for a single-item measure of reputation is the question “Please indicate, what kind of reputation does company x have in the public?” measured on a seven-point scale with 1 = “a very good reputation,” 7 = “a very bad reputation”; a multi-item scale might be based on the question “Please indicate, what kind of reputation does company x have concerning the following attributes?” with a list of attributes/facets of reputation to be evaluated on a similar scale (Helm 2007a).

Besides the multi-item measurement approach, the application of multidimensionality gives the opportunity to split more complex constructs into subsequent concrete entities. Various studies dealt with a multidimensional view of reputation (Chun 2005; Money and Hillenbrand 2006; e.g., see Aaker 1997; Davies et al. 2003; Fombrun et al. 2000)Footnote 2 and collapsed the amount of manifest items into fewer dimensions or lower order factors. These lower order factors contribute to the higher order factor “reputation.”Footnote 3 Figure 2 shows an example for such a measurement model which uses “sympathy” and “competence” as two distinctive components of reputation (Schwaiger 2004). It should be borne in mind that reputation is not measured directly which may reduce managerial insights into reputation.

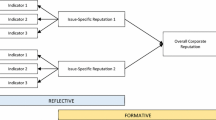

Another approach to cope with the possibly multidimensional structure of reputation that provides clearer guidance for managerial purposes is to make use of formative measurement models. Indicators of the reputation construct are most often captured via the evaluation of social expectations (Berens and van Riel 2004). This implies that an evaluation of corporate reputation is based on salient characteristics of a firm (de Castro et al. 2006) that describe how it handles different stakeholder relationships. Such an approach is, for instance, applied by Helm (2005) who uses ten indicators (called the “facets” of reputation) to measure corporate reputation: quality of products, commitment to protecting the environment, corporate success, treatment of employees, customer orientation, commitment to charitable and social issues, value for money of products, financial performance, qualification of management, and credibility of advertising claims. In such a case, reputation can be conceptualized as a formative construct meaning that the indicators lead to the construct as inputs. Reputation then is an aggregation of all its indicators such as product quality, treatment of employees, etc. Reputation is conceived as the result of entrepreneurial efforts and not vice versa. Therefore, the indicators cause reputation.Footnote 4 Such indicators do not have to be correlated or to represent the same underlying dimension (Helm 2005). On the other hand, corporate reputation can be understood as a reflective construct. This would mean that the indicators – such as product quality, management quality, etc. – are alternative outcomes of reputation. Reputation would lead to these effects meaning that reputation determines the quality of products, the quality of management, and so forth (Helm 2005).Footnote 5

A common problem when measuring corporate reputation lies in the use of explorative factor analysis for testing unidimensional solutions or the application of reflective measurement models in confirmatory factor analysis. Here, every extracted factor has to be regarded as unidimensional, thus every item needs to highly correlate with every other item of the construct (Bagozzi 1994). In a psychological sense, every unidimensional construct is based on an evaluation of certain liked or disliked indicators, where the most liked or disliked indicator (or the one deemed most important) may have a spill-over effect onto the remaining indicators. This phenomenon is also known as “irradiation effect” (Riezebos et al. 2003). Moreover, unidimensional solutions are subject to a general impression halo effect where “a rater’s overall evaluation or impression of a reputation object leads the rater to evaluate all aspects of performance in a manner consistent with the general evaluation or impression” (Caruana and Chircop 2000; Thorndike 1920). As outlined earlier, high correlations between a single-item measure and a multi item measure are often wished for (Bergkvist and Rossiter 2007; Nagy 2002). This also means that a single-item measure may serve as a “global” indicator stakeholders (or respondents) use to determine their evaluation of the indicators of a multi-item measure (the facets of reputation). Hence, the answer to the question asked by Caruana and Chircop: “Could the ‘halo’ be the ‘reputation’?” (2000, p. 54) is “yes” in those cases where stakeholders/respondents use their global impression of reputation (as manifested in the single-item measure) to infer the “quality of products,” “treatment of employees,” etc. that form the multi-item measure of reputation. The latter construct then lacks in validity, a problem which becomes prominent if respondents are not really familiar with a firm and unable to judge its diverse entrepreneurial efforts captured by the facets of reputation in a multi-item measure. It needs to be recognized by the empirical researcher that not all stakeholders have a distinct knowledge of the multiple reputational facets of a specific firm and their parameter values (Helm 2007a). This problem is also implied by Schultz et al. (2001) who observe that respondents often use “intuition” when answering multifaceted scales of reputation and that they are unable to discriminate finely between the criteria they are asked to quantify. “Over time, […] particular endeavours get lost in general impressions of how the company performs” (Schultz et al. 2001, p. 37).

An extension of two-dimensional models has been developed by Fiedler (2006) who measures corporate brand image. Although we pointed out that the meaning of this construct is not identical to corporate reputation, his conceptualization offers insights for a more elaborated measurement model for reputation. According to Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), attitudes can be divided into an affective, a cognitive, and an intentional component. Fiedler integrates the first two components and measures the affective part of corporate image using the reflective mode and the cognitive part via the formative mode; the indicators of the latter construct are adapted to the six stakeholder groups he integrated in his empirical study. In addition, a third formative construct was incorporated measuring potential differences between the stakeholder-specific cognitive image components (see Fig. 3).

Common Standardized Measures for Reputation

One of the most commonly used standardized quantitative approaches of measuring corporate reputation is the several ranking lists published by Fortune magazine as for instance Fortune’s Most Admired Companies (FMAC). Top managers are asked to evaluate a set of eight criteria on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 = “poor” to 10 = “excellent” (Fombrun and Shanley 1990). The criteria (indicators) are Quality of Management; Financial Soundness; Quality of Products and Services; Ability to Attract, Develop, and Keep Talented People; Innovativeness; Responsibility for the Community and the Environment; Long-term Investment Value, Wise Use of Corporate Assets. Evaluations of reputational indicators are used to build a score which results in rankings of companies according to specific dimensions (represented by the indicators, such as innovativeness) and an overall (national or global; industry-specific or total) ranking of companies. In 2007, the most admired company was General Electric, followed by Toyota Motors and Procter & Gamble.Footnote 6 While it is not entirely clear how the FMAC was developed and if standard procedures for developing construct measures have been adhered to, the data of the ranking have been used for many scientific publications (Chun 2005; Bromley 2002).

Another prominent example for a standardized measurement approach used mostly for commercial purposes is the so-called RepTrakFootnote 7 which is based on the Reputation Quotient (RQ). Both measures were developed by the Reputation Institute (RI) (Fombrun et al. 2000). Again, it is not clear how the construct measure was developed and how the reputation rating scores are calculated. Within RepTrak, 23 reputation indicators are combined to form seven core dimensions (products and services, innovation, workplace, governance, citizenship, leadership, and performance) which represent the building blocks of the so-called RepTrak Reputation Score Card. For benchmarking purposes, the RI offers a so-called RepTrak Pulse Score. In the worldwide study of 2007, the highest score was reached by LEGO from Denmark, followed by IKEA from Sweden, and Barilla from Italy.Footnote 8

Besides these commercially used standardized measures, an abundance of different approaches has been developed and published in academic papers. Here, structural equation modeling (SEM) approaches are commonly used in order to measure latent constructs such as corporate reputation, its antecedents, and its consequences and to test assumed relationships between them (MacMillan et al. 2005; Money and Hillenbrand 2006). Figure 4 depicts a full SEM model.

Basically, management-oriented approaches rather focus on comparisons between companies for benchmarking purposes like FMAC or comparisons between reputational dimensions within a single company like the RepTrak Reputation Score Card, whereas academic studies rather deal with the generalization of research findings concerning relationships between various constructs. Quantitative approaches seem to be prevalent amongst reputation measures although qualitative methods like, e.g., focus groups or case studies are available as well (Walsh and Wiedmann 2004; Caruana and Chircop 2000). In order to assess and compare the results of corporate reputation measurement, outputs such as league tables, RQs (or scores), rankings, or benchmarks (Bromley 2002) are the most commonly used ones.

Stakeholder Adaptation of Reputation Measures

A central issue in reputation measurement is whether different stakeholder groups perceive reputation identically or whether different kinds of reputations exist. Some authors conducted multigroup comparisons of reputational perceptions between stakeholder groups without adapting the measurement models to the specific stakeholder context (Fombrun et al. 2000; Helm 2007a), others adapt (parts) of their measurement model to the stakeholder context (Fiedler and Kirchgeorg 2006). Whether all types of stakeholders base their perceptions of reputation on the same fundamental set of dimensions or indicators is seen controversially (Bromley 2002; Fombrun et al. 2000). Hence, Fombrun and Shanley (1990) ask “Do firms have one reputation or many?” Considering our definition of reputation, it may be suggested that (certain) reputational perceptions converge across stakeholder group boundaries (Fiedler 2006) forming a general reputation of a firm. In this case, corporate reputation is taken to signify a collective’s view of a firm which tends to revolve around broad dimensions (Fombrun et al. 2000; Helm 2007a). Contrarily, Dowling (2004) cautions that investigations of reputation call for an adaptive approach meaning that a specific measurement model for reputation needs to be developed for each stakeholder group leading to as many reputations as there are stakeholder groups or individuals.Footnote 9 Neville et al. (2005, p. 189) claim that firms “may have different reputations with individual stakeholder group members as expectations vary from one member to the next.” This reduces possibilities to compare results of reputation measurements which is problematic from a managerial perspective. Helm (2007a) finds empirical evidence to support that there is common ground amongst different stakeholder groups in interpreting the construct of reputation; but there is also evidence for a need to adapt measures to specific stakeholder groups. Only such an approach is likely to capture the heterogeneity of stakeholder groups with respect to their subjective views of a company’s reputation (Dowling 2001).

If there is a content-driven need for a differentiation of reputation, an incorporation of additional stakeholder-specific components would be a possible compromise between these viewpoints (Fiedler and Kirchgeorg 2006). A cognitive stakeholder-specific component as used by Fiedler (2006) could capture the assumed relative importance of the manifest reputation items since performance domains of the company are said to differ in their importance for specific stakeholder groups such as customers, employees, or shareholders (Helm 2007b; MacMillan et al. 2005) For instance, “financial soundness” is a most relevant indicator of reputation if financial analysts are surveyed but can hardly be determined by consumers, “treatment of employees” is most relevant to employees, etc. “The strength and homogeneity of the individuals’ impressions in a group comprise reputation; if the members all have weak or differing opinions, no clear reputation is formed” (Sjovall and Talk 2004, p. 270). Further research is necessary to come to a conclusion whether reputation measurement models should be standardized or adapted to stakeholder group-specific concerns. Figure 5 shows such an adapted multigroup reputation measure embedded in an SEM model. For managerial purposes, such models might be too complex, explaining the preference of practitioners for standardized, nonadapted rankings such as the FMAC or RepTrak.

Summary and Directions for Further Research

Our analysis of current measurement practice regarding the construct of reputation has indicated a number of challenges that still need to be addressed in future studies of reputation. Specifically, the issue when single items are better suited than multi-item measures, whether reputation can be conceptualized as a unidimensional construct, or whether sub-constructs or dimensions should be integrated in measurement models need to be solved on a conceptual level. On a more practical level, it needs to be decided whether the researcher understands reputation as a formative or reflective construct and whether the respondents have sufficient knowledge to validly evaluate reputational items. The issue of how to find indicators to be included in a multidimensional measure was not covered in this chapter but has been dealt with extensively in the literature on conceptualizing measurement models (see, e.g., Churchill 1979; Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer 2001; Rossiter 2002; Helm 2005). On a goal-oriented level, the researcher needs to decide whether developing a stakeholder-adapted measurement tool is more effective than using the same general approach for all stakeholder groups included in the study.

Appropriate measurement of reputation is the foundation for managing this valuable asset of the firm. It enables the reputation manager to analyze past and current reputation by ANOVA or time-series models; to compare reputation of different organizational functions or subsidiaries (internal benchmarking) or of the firm and its competitors or other institutions (external benchmarking), within or across industries; and to steer and improve reputation in specific performance domains of the company on a regional, national, or global level.

Notes

- 1.

Due to identification problems within the covariance-based structural equation modeling approach, an additional single-item measure of reputation can be used to achieve identification (Jarvis et al. 2005).

- 2.

Aaker (1997) identified Sincerity, Excitement, Competence, Sophistication, Ruggedness as first-order factors; Davies et al. (2003) identified Agreeableness, Competence, Enterprise, Chic, Ruthlessness, Machismo, Informality as second-order factors; Fombrun et al. (2000) identified Products & Services, Innovation, Workplace, Governance, Citizenship, Leadership, and Performance as first-order factors of reputation.

- 3.

A detailed description of all kinds of combinations is given by Jarvis et al. (2005).

- 4.

Technically spoken: reputation is – when measured via formative mode – a latent dependent metric index variable estimated by using multiple regression analysis.

- 5.

Within reflective measurement models all items have to be highly correlated. A conceptual problem can occur if an increase in e.g., product quality must not necessarily be accompanied by an increase of, e.g., wise use of financial assets.

- 6.

http://www.money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/mostadmired (download 2008-01-23).

- 7.

http://www.reputationinstitute.com/reptrakpulse (download 2008-01-23).

- 8.

http://www.reputationinstitute.com/reptrakpulse (download of Global RepTrak Pulse 2007 report, 2008-01-23).

- 9.

Helm (2007b, p. 239) describes three perspectives of the definition and measurement of stakeholder perceptions of corporate reputation, namely (1) the existence of an attitude in the mind of individuals; (2) perceptions that are matched within stakeholder groups; and (3) certain reputational perceptions forming a general reputation of the firm across (all) stakeholder groups.

References

Aaker JL (1997) Dimensions of brand personality. J Mark Res 34:347–356

Bagozzi RP (1994) Structural equation models in marketing research: basic principles. In: Bagozzi RP (ed) Principles of marketing research. Blackwell, Oxford, pp 317–385

Barnett ML, Jermier JM, Lafferty BA (2006) Corporate reputation: the definitional landscape. Corp Reput Rev 9(1):26–38

Barney J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag 17(1):99–120

Berens G, van Riel CBM (2004) Corporate associations in the academic literature: three main streams of thought in the reputation measurement literature. Corp Reput Rev 7(2):161–178

Bergkvist L, Rossiter JR (2007) The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. J Mark Res 44(2):175–184

Bromley D (2002) Comparing corporate reputations: league tables, quotients, benchmarks, or case studies? Corp Reput Rev 5(1):35–50

Caruana A, Chircop S (2000) Measuring corporate reputation: a case example. Corp Reput Rev 3(1):43–57

Chun R (2005) Corporate reputation: meaning and measurement. Int J Manag Rev 7(2):91–109

Churchill GA (1979) A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J Mark Res 16:64–73

Davies G, Chun R, Vinhas da Silva R, Roper S (2001) The personification metaphor as a measurement approach for corporate reputation. Corp Reput Rev 4(2):113–127

Davies G, Chun R, Vinhas da Silva R, Roper S (2003) Corporate reputation and competitiveness. Routledge, London

de Castro GM, López JEN, Sáez PL (2006) Business and social reputation: exploring the concept and main dimensions of corporate reputation. J Bus Ethics 63(4):361–370

Diamantopoulos A, Winklhofer HM (2001) Index construction with formative indicators: an alternative to scale development. J Mark Res 38:269–277

Dollinger MJ, Golden PA, Saxton T (1997) The effect of reputation on the decision to joint venture. Strat Manag J 18(2):127–140

Dowling G (2001) Creating corporate reputations: identity, image, and performance. Oxford Press, Oxford

Dowling G (2004) Journalists’ evaluation of corporate reputations. Corp Reput Rev 7(2):196–205

Fiedler L, Kirchgeorg M (2006) Impact of brand image components on behavioral intentions of stakeholders: insights for corporate branding strategies. In: Proceedings of the AMA Conference 2006, Chicago

Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA

Fombrun C, van Riel C (1997) The reputational landscape. Corp Reputation Rev 1(1):5–13

Fombrun CJ (2007) List of lists: a compilation of international corporate reputation ratings. Corp Reput Rev 10(2):144–153

Fombrun CJ, Shanley M (1990) What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Acad Manag J 33(2):233–258

Fombrun CJ, Gardberg N, Sever JM (2000) The reputation quotientSM: a multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. J Brand Manag 4(7):241–255

Gardberg N, Fombrun C (2002) The global reputation quotient project: first steps towards a cross-nationally valid measure of corporate reputation. Corp Reput Rev 4(4):303–315

Helm S (2005) Designing a formative measure for corporate reputation. Corp Reput Rev 8(2):95–109

Helm S (2007a) One reputation or many? Comparing stakeholders’ perception of corporate reputation. Corp Commun 12(3):238–254

Helm S (2007b) The role of corporate reputation in determining investor satisfaction and loyalty. Corp Reput Rev 10(1):22–37

Helm S (2007c) Exploring the impact of corporate reputation on consumer satisfaction and loyalty. J Consum Behav 5:59–80

Jarvis SB, Podaskoff PM, MacKenzie SB (2005) The problem of measurement model misspecification in behavioral and organizational research and some recommended solutions. J Appl Psychol 90(4):710–730

Larkin J (2003) Strategic reputation risk management. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Lewellyn PG (2002) Corporate reputation. Focusing the zeitgeist. Bus Soc 41(4):446–455

MacMillan K, Money K, Downing S, Hillenbrand C (2005) Reputation in relationships: measuring experiences, emotions and behaviors. Corp Reput Rev 8(3):214–232

Money K, Hillenbrand C (2006) Using reputation measurement to create value: an analysis and integration of existing measures. J Gen Manag 32(1):1–12

Nagy M (2002) Using a single-item approach to measure facet job satisfaction. J Occup Organ Psychol 75(1):77–86

Neville BA, Bell SJ, Mengüç B (2005) Corporate reputation, stakeholders and the social performance-financial performance relationship. Eur J Mark 39(9/10):1184–1198

Newell SJ, Goldsmith RE (2001) The development of a scale to measure perceived corporate credibility. J Bus Res 52(3):235–247

Riezebos R, Riezebos HJ, Kist B, Kootstra G (2003) Brand management: a theoretical and practical approach. Pearson, New York, NY

Rossiter JR (2002) The C-OAR-SE procedure for scale development in marketing. Int J Res Mark 19:305–335

Schultz M, Mouritsen J, Gabrielsen G (2001) Sticky reputation: analyzing a ranking system. Corp Reput Rev 4(1):24–41

Schwaiger M (2004) Components and parameters of corporate reputation – an empirical study. Schmalenbach Bus Rev 56(1):46–71

Sjovall AM, Talk AC (2004) From actions to impressions: cognitive attribution theory and the formation of corporate reputation. Corp Reput Rev 7(3):269–281

Thorndike EL (1920) A constant error in psychological rating. Journal of Applied Psychology 4:25–29

van Riel CBM, Stroeker NE, Maathuis OJM (1998) Measuring corporate images. Corp Reput Rev 1(4):313–326

Walsh G, Wiedmann KP (2004) A conceptualisation of corporate reputation in Germany: an evaluation and extension of the RQ. Corp Reput Rev 1(4):304–312

Wartick SL (2002) Measuring corporate reputation. Bus Soc 41:371–392

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Helm, S., Klode, C. (2011). Challenges in Measuring Corporate Reputation. In: Helm, S., Liehr-Gobbers, K., Storck, C. (eds) Reputation Management. Management for Professionals. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-19266-1_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-19266-1_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-19265-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-19266-1

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)