Abstract

Reasons for residential moves vary across the life-course. While deteriorating health and increasing needs for support by children have been suggested to be the main motivations for moves in later life, one as yet under-investigated reason might be the wish to reduce home equity, thus alleviating financial distress in old age.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Housing and Financial Distress

Reasons for residential moves vary across the life-course. While deteriorating health and increasing needs for support by children have been suggested to be the main motivations for moves in later life, one as yet under-investigated reason might be the wish to reduce home equity, thus alleviating financial distress in old age.

Housing is the most widely held asset and, therefore, an important component of household wealth in many European countries. At the same time, it provides services: by owning their home, consumers can insure against the risk of housing service inflation (Sinai and Souleles 2005). For this reason, it is not surprising to find that very high proportions of elderly households own their home in all SHARE countries. However, if they want to keep a good standard of living, they should release home equity by either taking up a mortgage, or by downsizing, or both.

We know from the first two waves of SHARE, that large fractions of households report difficulties making ends meet. This is particularly true of renters, but is quite common among home-owners as well. In fact, Angelini et al. (2009) argue that the failure to use financial instruments that reduce home equity (like mortgages or reverse mortgages) late in life is partly responsible for financial hardship among elderly Europeans. In this paper we document the extent to which elderly Europeans downsize their home equity position by trading and show that also the downsizing decision is related to the development of mortgage markets.

The development of mortgage markets varies a lot across European countries. In some countries credit rationing policies were used by central banks to fight inflation until a few decades ago, and until recently banking sector competition was severely restricted. In other countries the poor operation of the judicial system has also been blamed for the limited development of mortgage markets. In all countries low levels of financial literacy may also account for reluctance to use debt instruments and failure to use them well.

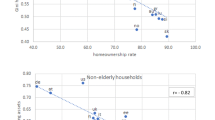

There is a striking correlation between indicators of mortgage market development and proportions of elderly households reporting financial distress. For instance, in Fig. 8.1 we plot the proportion of households participating in the second wave of the SHARE survey who report finding it difficult or very difficult to make ends meet in 2006–2007 against a very crude indicator of mortgage market development, that is the typical loan-to-value ratio on mortgages over the 2003–2006 period. There is a clear negative relation (the correlation is −0.59), despite the fact that high loan-to-value ratios in countries like Spain and Greece probably do not apply to ageing mortgagors.

Calza et al. (2009), propose a much more sophisticated index (not available for Switzerland, Poland and the Czech Republic) that takes into account not only loan to value ratio, but also opportunities for and costs of equity withdrawal, typical terms and conditions of mortgage contracts, and so on. Figure 8.2 clearly shows that there is a strong, negative relation between mortgage market development and financial distress in old age (the correlation is −0.54). Although this relation might be partly driven by the fact that Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark are very different from the other countries, it confirms the evidence reported in Fig. 8.1. Of course, in countries where mortgage refinancing is not available and mortgages are mostly short term, equity withdrawal cannot be achieved by use of debt instruments.

A more radical way to reduce home equity is to sell and move into rented accommodation. This is relatively uncommon, though. Chiuri and Jappelli (2010) use repeated cross section data to show that few households cease to be home owners late in life. In Chap. 7, Angelini, Laferrère and Weber document a similar pattern using life histories data.

We instead document the extent to which elderly Europeans downsize late in life by selling an expensive home and buying a cheaper one. We do this by exploiting a unique feature of the SHARE life history data, which contain individual records of housing transactions over the entire life of the respondents. For each sale or purchase, respondents are asked to report the value of the property, and this allows us to determine whether the respondent was trading down or up.

2 How Often Do Europeans Move?

A first indication of housing mobility is given by the total number of homes individuals ever had in their lifetime (so far). This information is available in the data, and can be compared across countries, to the extent that the age distribution is the same.

Figure 8.3 shows that there are major differences across European countries: Northern Europeans report an average number of 6–8 different main residences over their life course, while Southern and Eastern Europeans typically report less than four. Given that this includes the parental home, an average Greek, Polish or Czech apparently moved only at the time of nest-leaving.

Figure 8.4 shows that the average number of main residences hardly increases with age, with the notable exceptions of Denmark and the Netherlands. For instance, younger Greeks and Swedes have already experienced more mobility than their elders. This picture cannot distinguish between age and cohort effects, but if moves in old age were common we would likely observe increasing patterns. Note also that in most countries (with the partial exceptions of the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark, as far as the first wave of SHARE is concerned), nursing home residents were not included in the baseline sample and this might bias downward the estimated number of moves for the 75+. The extent of the bias is likely to vary across regions – it is well known that nursing homes are more rarely used in Southern European countries.

If we are interested in trading down in old age, it makes sense to look at the number of main residences owned or rented after age 50. We know from previous studies that non-durable consumption peaks around that age (Attanasio et al. 1999), and household size also tends to decrease after that age (with important cross country differences). Figure 8.5 shows that in most countries a majority of individuals never change main residence after they reach age 50: only in Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands the average number of main residences exceeds 1.5.

3 When Do Older Europeans Move?

In Fig. 8.6 we present histograms of ages at which a home purchase or sale took place for four countries where trading decisions are relatively frequent: Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and France. The figure shows that a vast majority of transactions takes place relatively early in life, and certainly before retirement age (that we can assume to be around 60, even though it varies a lot across countries, as shown in Angelini et al. 2009).

Figure 8.7 shows the age distribution of trading up decisions, that is, of cases where the respondent bought a more expensive home. Figure 8.8 shows instead for the same countries the age distribution of the more infrequent trading down decisions. Comparing these two figures we see that in all four countries trading down takes place later in life compared to trading up.

Finally, in Fig. 8.9 we provide direct evidence on the frequency of home equity withdrawal in later life by means of moving homes. The graph presents the average number of moves that involve trading up, trading down or going from home-ownership into non-homeownership (labeled as “own–rent” for simplicity sake) that have taken place after the respondent reached age 50. In all countries, there are more moves that involve some equity release than trading up transactions. We also find that in those countries where mortgage markets are least developed (Southern and Eastern European countries), the number of overall moves are quite low.

4 Why Don’t Older Europeans Trade Down More?

The striking feature that emerges from our analysis is that the low development of mortgage markets not only limits the ability to withdraw equity by using mortgage debt, but also has a negative correlation with the number of own–own transactions later in life, as shown in Figs. 8.10 and 8.11 (the correlation of the number of own–own transaction with the loan-to-value ratio is 0.66, while it is 0.87 with the mortgage market index).

In both cases, we show on the vertical axis the ratio of the number of own–own housing transactions carried out after age 50 to the number of homeowners at age 50. On the horizontal axis we report the two indicators of mortgage market development that we already introduced in the introduction, namely the typical loan-to-value ratio for mortgages and the broader mortgage market index constructed by Calza et al. (2009).

5 Conclusions

The availability of recall price data on home purchases and sales is a unique feature of the third wave of SHARE. These data can be used to address the question of whether elderly Europeans trade down in old age, as a way to avoid becoming house-rich, cash-poor.

The importance of trading down as a form of equity release depends heavily on financial and mortgage markets access and regulations, as well as on the availability of public housing and long term care accommodation. In most European countries financial instruments that allow equity release are unavailable or relatively uncommon, and cheap public housing is a scarce resource (particularly for the elderly), so trading down may well be the only way to generate a cash flow out of the available home equity. But the evidence we produced suggests that in those countries where mortgage markets are less well developed, lower fractions of home-owners trade down by selling and buying, and higher fractions of homeowners report financial distress.

References

Angelini, V., Brugiavini, A., & Weber, G. (2009). Ageing and unused capacity in Europe: Is there an early retirement trap? Economic Policy, 59, 463–508.

Attanasio, O. P., Banks, J., Meghir, C., & Weber, G. (1999). Humps and bumps in lifetime consumption. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 17(1), 22–35.

Calza, A., Monacelli, T., & Stracca, L. (2009). Housing finance and monetary policy. European Central Bank, Working Paper 1069.

Chiuri, M. C., & Jappelli, T. (2010). Do the elderly reduce housing equity? An international comparison. Journal of Population Economics, 23, 643–663.

Sinai, T., & Souleles, N. S. (2005). Owner-occupied housing as a hedge against rent risk. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120, 763–789.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Angelini, V., Brugiavini, A., Weber, G. (2011). Does Downsizing of Housing Equity Alleviate Financial Distress in Old Age?. In: Börsch-Supan, A., Brandt, M., Hank, K., Schröder, M. (eds) The Individual and the Welfare State. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-17472-8_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-17472-8_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-17471-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-17472-8

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)