Abstract

In this chapter, Albareda and Hajikhani propose a literature review and bibliometric analysis on innovation for sustainability (IfS). Applying the Network Analysis Interface for Literature Studies (NAILS) toolkit, we study the impact and dissemination of five key IfS goal-oriented discussions: strategic, operational, organizational, collaborative and systemic. The strategic and operational discussions are the most cited, including major papers on strategic concepts and the development of operational changes structuring the research. Our bibliometric analysis shows how, since 2002, IfS has expanded from business management, strategy, innovation and operations connecting to the main discussion in environmental sciences, environmental engineering and ecology. The main challenge for researchers is to build scientific knowledge that has a real impact in organizations and businesses. Managers and entrepreneurs can use these five-oriented goals of IfS to understand how to apply IfS goals into real practices.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last few decades, a growing number of organizations have embarked on a path in which sustainability has become a core innovation driver (Boons and Wagner 2009; Hart and Milstein 2003; Nidomulu et al. 2009). The growing attention paid to sustainable development, earth system impacts and planetary boundaries (e.g., climate change, natural resource scarcity and pollution) has turned the focus to innovation for sustainability (IfS) (Blowfield et al. 2007) as a means to solve societal and environmental challenges (Tukker 2005) while bring to the markets new sustainable products and services (e.g., renewable energy) (Adams et al. 2016; Boons and Lüdeke-Freund 2013; Bocken et al. 2014), fostering system-wide changes (Inigo and Albareda 2016) and transforming economic and industrial systems toward sustainable development (e.g., circular economy) (Gladwin et al. 1995). Many companies are increasingly changing the way they innovate, fostering integrated economic, social and environmental value creation (Elkington 1997; Klewitz and Hansen 2014) and, therefore, enhancing sustainability system transformation (Geels 2010), including new forms of sustainable business models (Bocken et al. 2014).

In this chapter, we focus on the growing literature on IfS over the last two decades (Hansen and Grosse-Dunker 2013). We present a bibliometric literature review to illustrate how complex research in this area has spread across fields of research including innovation management, economics, environmental engineering, environmental sciences and ecology. We expand previous literature reviews (Adams et al. 2016; Bocken et al. 2014; Boons and Lüdeke-Freund 2013; Inigo and Albareda 2016; Nidomulu et al. 2009), providing an in-depth understanding of how IfS research issues and themes are organized in five key goal-oriented discussions. Following a review of the core literature, we propose a bibliometric analysis to study the impact of this literature over time and its dissemination across other academic research fields in the peripheral literature. The core literature includes the initial research on IfS and the seminal concepts, while the peripheral literature includes research that has crossed the original research parameters as well as other broad empirical analyses (Small 1973).

Literature Review: Methods

In the first part of the literature review, we apply an integrative analysis of IfS codifying the main concepts and theories connected to IfS in management, organization and innovation studies and in environmental engineering over the last two decades. We first selected the core literature using a list of keywords,1 aiming to understand IfS research in business and organizations into core topics. This analysis classifies the literature in five key goal-oriented discussions that frame the main themes studied by researchers: strategic, operational, organizational, collaborative and systemic IfS. This analysis also comes after prior systematic and integrative literature research analysis done by Adams et al. (2016), and Inigo and Albareda (2016). The second part studies the evolution and dissemination of the IfS concept in the broader scientific and academic debate (Glänzel 2015). We conducted a bibliometric data analysis using the Network Analysis Interface for Literature Studies (NAILS)2 toolkit, designed in August 2015 by a part of our research team (Knutas et al. 2015). The NAILS statistical and Social Network Analysis (SNA) on bibliometric data has been featured in concept emergence and dissemination (Hajikhani 2017) and patent portfolio comparative analyses (Ranaei et al. 2016). We applied a four-step process as follow:

- Step 1::

-

We collected a set of keywords with input from a panel of experts to initiate the core literature selection. We constructed our search query with initial keywords and Boolean operators, using the Web of Science (WoS) as a search database.3 This led to a total of 6324 papers with the full bibliometric data available for further analysis.

- Step 2::

-

We refined our initial search, with downloaded bibliometric data bundled by a compression tool to upload into NAILS. As a result, we generated a tailor-made report providing abstract/keyword analyses, productive authors/journals and recommendations on top publications according to citation data. We used the NAILS report in the expired review process. This resulted in 56 core literature pieces (online report: https://goo.gl/ECYcdd).

- Step 3::

-

We explored the dissemination of this “core literature” (Small 1973) which included a total of 484 relevant research papers (online report: https://goo.gl/aLwH43). The relevance ratio highlights the importance of the core literature based on the number of citations received. The “times cited per year” variable is another indication of the quality of papers based on the average citations they receive each year.

- Step 4::

-

We delineated the perception of core literature by identifying the most relevant peripheral literature in a multidisciplinary field of science. In keeping with Cooper et al. (2009), we studied citation connections to understand the relevance of IfS as a scientific topic of discussion. The NAILS tool calculated new indexes, including the publications’ relevance, their dates and research fields. We established the rule for peripheral papers to ensure that they cited a minimum of 3 core literature publications. This served as a proxy to ensure that the papers are moving the core discussions forward.

Business Innovation for Sustainability: Key Discussions

Research on IfS first appeared approximately in 2002 (Hart and Christensen 2002; Hart and Milstein 2003) adopting prior concepts forested by seminal sustainable development documents, the Brundtland Report (WCED 1987) or the triple bottom line (Elkington 1997). We also want to highlight that IfS research is sourced on previous seminal work in business sustainability theory which appeared as of 1995. The key business sustainability theoretical papers proposed a paradigm shift toward organizations and sustainable development (Elkington 1997; Gladwin et al. 1995; Hart 1995; Porter and van der Linde 1995; Shrivastava 1995; Shrivastava and Hart 1995). The main difference between sustainable business and IfS is that the second group of research focus mainly on the integration between sustainability within innovation. Extending previous analyses (Adams et al. 2016; Inigo and Albareda 2016), the results of this literature review codify and classify the literature of IfS into five main discussions: strategic, operational, organizational, collaborative and systemic. These five discussions frame the main topics and goals adopted by management, organization and engineering researchers studying how companies are able to transform their innovation tools, management and goals integrating the principles of sustainable development. This include three main changes: transforming innovation from technical sustainability (e.g., life-cycle analysis) to changing people mind-set (e.g., triple bottom line), changing IfS as stand-alone activity within the company toward a whole strategic and organizational practices and changing the vision of the firm from insular market impacts (e.g., sustainable products and services) to broad societal systemic change (e.g., sustainable business models, circular economy) (Adams et al. 2016).

Strategic IfS

The main discussion in IfS literature encompasses an analysis of its strategic dimensions, primarily related to sustainable value creation (Hart and Christensen 2002; Hart and Milstein 2003; Zollo et al. 2013), and core competences (Chen 2008). Inigo and Albareda (2016) study three different challenges. The first is connected to market orientation and sustainable value creation (Boons and Wagner 2009; Shrivastava 1995) and implies adopting a pathway to build sustainable business models (Bocken et al. 2013; Inigo et al. 2017). This connects IfS to radically different economic, social and environmental value creation processes (Di Domenico et al. 2010; Figge and Hahn 2004), and sustainable business models (Bocken et al. 2014; Stubbs and Cocklin 2008). The second challenge is based on how IfS transforms business strategy, implying new approaches to traditional strategic management and enhancing new forms of business organizing and bottom-of-the-pyramid structures (Prahalad and Hart 2001; Prahalad 2012), social enterprises and hybrid organizing (Dacin et al. 2011) and the changes adopted by firm fostering IfS (Arnold and Hockerts 2011; Schaltegger and Wagner 2011). The third challenge connects IfS to performance and benefits, including economic performance and cost analyses (Bos-Brouwers 2010).

Shared value creation focuses on the interconnections between economic progress and societal challenges by re-conceiving products and markets, redefining productivity in the value chain and enabling local cluster developments (Porter and Kramer 2011). Social innovation goes beyond economic benefits and mainly focuses on innovation as a key tool to solve the most urgent grand challenges (Nicholls and Murdoch 2012). Social innovation connects to social entrepreneurship as a core driver (Hall 2014; Hockerts and Wüstenhagen 2010; McGowan and Westley 2015). Responsible innovation has emerged in the last few decades, emphasizing a mutual and responsible approach among multiple stakeholders participating and affected by innovation; the goal is to anticipate the outcomes and the negative impacts and shared responsibilities (Von Schomberg 2013).

Operational IfS

Operational IfS is the second main discussion. Operational IfS studies how businesses transform operational processes into more eco-efficient procedures (WBCSD 2000). Operational optimization aims to change production systems to integrate new process-oriented knowledge and tools (e.g., eco-efficiency, sustainable life-cycle assessment and environmental management) across the whole value chain (Adams et al. 2016; Carrillo-Hermosilla et al. 2010). Operational IfS involves three main challenges (Inigo and Albareda 2016). The first is ensuring sustainability across the whole life cycle and value chain, adopting waste management, industrial symbiosisand circular economy approaches (Sharma and Iyer 2012). The second is based on product and service design, including eco-innovation and eco-design (Pujari 2006). The third is improving performance, adopting environmental management systems, impact minimization technologies and re-designing processes (Boons et al. 2013; Schaltegger and Burritt 2014).

Research on operational IfS mainly began with eco-efficiency (Ehrenfeld 2005; Hellström 2007; WBCSD 2000), fostering environmental efficient innovation tools and activities to include environmental impacts on company operations (Hansen et al. 2009; Harms et al. 2013). Eco-efficiency is a management approach that encourages businesses to search for environmental improvements that finally lead to integrated ecologic and economic benefits and foster new ways of doing business by integrating environmental and economic value creation (WBCSD 2000: 4). It goes beyond incremental efficiency, transforming operations with new systemic tools and strategies that promote radical and sustainable process innovation, affecting the entire life-cycle assessment across value chains and the industrial and innovation ecosystem (Chertow and Ehrenfeld 2012; Wagner 2008).

All of these changes connect eco-innovation (Del Río 2009), which is framed under different disciplines, technological change, systems analysis and operations research, industrial ecology and industrial economics (Del Río et al. 2010). Eco-innovation aims to change the environmental performance of consumption and production activities (Kemp et al. 2007). Early on in this century, eco-efficiency and eco-innovation have expanded to include: sustainable product innovation (Clark et al. 2009), eco-design (Dangelico and Pujari 2010) and clean technological changes (Horbach et al. 2012). Operational innovation also fosters sustainable supply chain management, life-cycle analysis (Melville 2010), industrial symbiosis (Mirata and Emtairah 2005) and industrial ecology (Boons et al. 2016).

Organizational IfS

The third discussion is the analysis of organizational transformation enhanced by IfS. Organizational IfS studies how business is changing their organizations, exploring new ways of organizing and managing IfS, as for example whole life-cycle thinking (Inigo and Albareda 2016; Seebode et al. 2012). According to Adams et al. (2016: 10), organizational transformation involves “a fundamental shift in mindset.” IfS is embedded in new multidisciplinary practices developed across departments and units, disseminating new strategic approaches and embedding sustainability as a core driver for innovation (e.g., waste to management) (Nidomulu et al. 2009; Sharma 2005). It does so in favor of a systematic organizational ecosystem, fostering leadership and radical IfS (e.g., slow business models) (Inigo et al. 2017).

There are three main challenges (Inigo and Albareda 2016). The first involves the development of new IfS capabilities (Van Kleef and Roome 2007), either promoting new organizational and relational capabilities and attracting new talent or training employees and innovation teams and managers. This also involves developing relational capabilities with external partners. The second challenge is addressing natural resource scarcity, promoting the efficient use of natural resources and innovative waste management, recycling, reusing and remanufacturing and creating value from waste. This strategy serves to innovate and create new value or promote new creativity or bricolage in scarce resource environments, fostering inclusive businesses (Halme and Korpela 2014). The third challenge involves new forms of organizing, including a shift in organizational mind-sets and in how to do business and innovate by creating shared value, integrating IfS into the companies’ culture and goals and thereby accelerating IfS (Jay and Gerard 2015). Compared to traditional technological and market-pull innovation, IfS is different because it requires a higher level of inter-organizational knowledge generation to address social and environmental challenges and intra-organizational dialogue and co-creation with societal and environmental stakeholders (Castiaux 2012; Rennings 2000). These capabilities include developing a system-wide view of the innovation process and learning and experimenting (Van Kleef and Roome 2007).

Collaborative IfS

The fourth core discussion is based on IfS’ collaborative nature with different societal and environmental partners and stakeholders (Nidomulu et al. 2009). IfS requires multiple partnerships and collaborative alliances between the company and technological partners but also with social and environmental stakeholders (De Marchi 2012; Goodman et al. 2017). Successful IfS becomes increasingly collaborative (Ghisseti et al. 2015). Furthermore, social and environmental stakeholders become key partners (Ayuso et al. 2011) through the adoption of new platforms and knowledge sources to stimulate creativity and overcome sustainability challenges (Ayuso et al. 2006). IfS also includes different dynamics such as design-thinking and co-creation workshops (Senge et al. 2008), root innovation (McGowan and Westley 2015), stakeholder dialogue (Ayuso et al. 2006), value-mapping (Bocken et al. 2013), supplier co-creation, user-focus innovation, societal co-creation (Hansen and Spitzeck 2011), social bricolage (Di Domenico et al. 2010), sustainable business models (Richter 2013) and reverse innovation (Govindarajan and Ramamurti 2011).

In this sense, collaborative IfS connects to three main challenges (Inigo and Albareda 2016). The first is to respond to public policies and new regulations (Horbach et al. 2012). The second is connected to how companies participate and co-create with local IfS networks and clusters, including industrial symbiosis (Paquin and Howard-Greenville 2012) and circular economy initiatives (Geissdoefer et al. 2017). The third challenge connects IfS to open innovation and how to build new partnerships (Ghisseti et al. 2015; Senge et al. 2008), including with new R&D partners and research centers (Chen and Hung 2014).

Systemic IfS

Finally, IfS literature connects to sustainable systems transformation (Adams et al. 2016; Loorbach et al. 2010). IfS aims to transform the industrial and capitalist economy toward sustainable development systems (Nill and Kemp 2009; Tukker et al. 2008). An example is a bottom-of-the-pyramid as a social enterprise (Prahalad and Hart 2001) that creates new opportunities for the poorest socioeconomic groups in both developing and developed countries. This implies emergent paradigms of social enterprises (Dacin et al. 2010) that take IfS as a core driver for sustainable change (Stubbs and Cocklin 2008) as well as sufficiency-driven business models (Bocken and Short 2015). There are three main challenges (Inigo and Albareda 2016). The first is based on how IfS helps to implement the system-level transition (Boons and Wagner 2009; Chertow and Ehrenfeld 2012; Geels 2011). The second involves transforming production and consumption dimensions (Hall 2002). The third challenge connects to the discussion on the emergence of sustainable enterprise organizing (Di Domenico et al. 2010; Hart 2012).

Bibliometric Analysis

In this section, we investigate the five discussions within core IfS publications over the years, their dissemination and citations, their time-evolving impact in other fields of research in the peripheral literature. We also analyze sustainable business theory as a main source for the dissemination of IfS literature.

Time-Evolving Impact

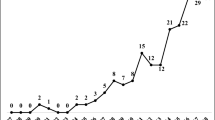

Since 1995, the scientific discussion on sustainable business theory has influenced the growing volume of IfS research (WCED 1987; Elkington 1997). IfS literature has grown considerably and quickly since 2002 (Hart and Milstein 2003). By studying the literature on IfS, we have detected the core literature and, accordingly, the peripheral literature. We study the time-evolving impacts of the core literature within the five discussion categories detailed above and show how it has expanded over time (see Fig. 3.1).

Core literature: Fig. 3.1 clearly indicates that the total citations received by the core literature in the five key IfS discussions have grown exponentially, featuring a sharper increase since 2006. Our research illustrates how papers on sustainable business theory achieving a 60% impact based on citations. Regarding the five main IfS discussions, the strategic and operational discussions are driving 26% of the impact and dissemination. The strategic IfS discussion is the most important. It includes the main seminal papers on strategy and IfS, sustainability and value creation and proposes the main concepts such as sustainable value creation, sustainable entrepreneurship and the bottom-of-the-pyramid approach. Operational IfS is also very important as it includes broad research on eco-efficiency, eco-innovation and life-cycle analysis, including the main empirical papers. Organizational and collaborative IfS discussions started later and have become more accepted within the academic community much more recently. Consequently, their impact through citations is smaller. Organizational IfS has recently had greater impact due to the growing volume of new research on organizational capabilities and different types of organizational transformations. Collaborative IfS has also grown considerably over the last few years due to the increasing attention to new forms of co-creation and collaboration between companies and social and environmental partners, open innovation and partnerships. Finally, systemic IfS is the newest discussion based on an analysis of sustainability transitions and societal changes.

Peripheral literature: Fig. 3.2 indicates the number of publications in both core and peripheral literature over time. Since we had the core literature discussions as identified by experts (56 papers), we were able to extract the papers which cited the core literature, referring to these as peripheral (almost 7000 papers).

The analysis of the literature ended with 425 peripheral papers. Our results clearly indicate that the major discussions on IfS in the “core literature” category have emerged in the past 15 years with a significant increase since 2010. The periphery has also been inspired, with a significant increase in publications as of 2010.

Fields of Research Dissemination

We also measured the impact and influence of IfS through its dissemination in other fields. We calculated the accumulated citations of each article in both the core and peripheral literature and tabulated them for the subject categories. Figure 3.3 represents the impact of the categories studied in core and peripheral literature by citation points. It is clear that, while there is an obvious overlap of the subject categories among core and peripheral literature, we can see a shift in subject categories. The peripheral literature shows a significant appreciation for new subjects such as “Environmental studies, Management” and “Economics, engineering, civil.” It is interesting to note that, while topics such as “Economics,” “Management, planning & development” and “Industrial engineering” in the core literature were highly cited, the peripheral literature hasn’t received the same attention citation-wise yet. However, on subject categories such as “Green & Sustainable science & technology,” “Management,” “Environmental studies, management” and “Business,” the peripheral literature shows an increase of appreciation via citation points compared to the core literature. Meanwhile, it is important to note that the peripheral literature has spread the notions of sustainability and innovation to areas such as psychology, agriculture, hospitality and forestry, a fact also recognized by the number of citations.

The top portion of Fig. 3.4 shows the frequency of the most popular publication venues (quantity of times which the venue publishes a paper) and popular ones (sorted by the number of received citations) for the IfS core literature. In addition, the bottom part of Fig. 3.4 illustrates the most popular and most cited venues for the peripheral publications.

The most popular publication venues for the core literature include Journal of Cleaner Production, Business Strategy and Environment, and Ecological Economies, while the most cited publications are Academy of Management Review, Journal of Economic Perspectives, and Harvard Business Review. For the peripheral literature, the most popular publications are Journal of Cleaner Production, Journal of Business Ethics, and Sustainability, while the top cited publication is Academy of Management Journal, Journal of Cleaner Production and Journal of Business Ethics.

Conclusion

We have presented a bibliometric study that explores how IfS literature has grown and developed over the last two decades. The main conclusion is that IfS core literature mainly comprises five key goal-oriented discussions: strategic, operational, organizational, collaborative and systemic IfS changes that frame the main topics and themes that researchers study to understand the main transformations undergone by businesses and organizations to embrace sustainable development principles and systems-based transformation (Geels 2010). The literature analysis is based on previous research (Adams et al. 2016; Bocken et al. 2014; Boons and Lüdeke-Freund 2013; Inigo and Albareda 2016; Nidomulu et al. 2009), providing an in-depth understanding of how IfS research issues and themes are organized. This bibliometric analysis shows the differences on impact and citation between different discussions. IfS literature is strong on strategic and operational themes that have been the two most impactful since 2002, including the main papers and theoretical and conceptual references in IfS. Contrarily, organizational, collaborative and systemic IfS discussions have emerged and increased in the last few years. This is mainly due to the current changes adopted by leading companies in IfS (e.g., Patagonia, Unilever) with growing collaboration between companies and social and environmental partners to build sustainable business models (e.g., slow fashion, waste to management, social innovation), in addition to sustainability transitions and societal change. In terms of the core literature, the two key fields of research are business management and economics followed by environmental sciences and environmental studies. This responds to the sources of IfS research on strategic and innovation management. The main fields of research for the peripheral literature show greater impact and interconnections with environmental studies, management and economics and civil engineering. Thus, we see a clear dissemination and interactions from business management toward more applied research in which the main IfS theories and ideas can be applied with empirical studies and real practices adopted by companies. In this sense, managers are embracing operational IfS changes, while exploring new sustainable business models, and co-creating new sustainable products and services (e.g., organic food, renewable energy, clean technologies). Managers and entrepreneurs can use these five-oriented goals of IfS to understand how to apply IfS goals into real practices. IfS literature analysis shows a road-map for managers to adopt new practices and strategies connected to strategic changes (sustainable business models, shared value, slow production, circular economy), operational optimization (eco-innovation, eco-efficiency, whole life-cycle analysis, clean technologies), organizational changes (social innovation, complex adaptive systems), collaborative pathways (with social and environmental stakeholders), and finally, system-change toward a new way to design and adopt production and consumption systems (e.g., circular economy). Beyond that, researchers and managers should work hand in hand to make IfS real and mainstream as a new way to do and integrate sustainability, innovation and value creation.

Notes

-

1.

Sustainability-oriented innovation, sustainable innovation, sustainability and innovation, innovation for sustainable development, social innovation, responsible innovation, green and eco-innovation.

-

2.

http://nailsproject.net/ online interface.

-

3.

WoS is maintained by Thomson Reuters and has 90 million documents indexed. It is considered one of the most important databases for scientific bibliometric data.

References

Adams, Richard, Sally Jeanrenaud, John Bessant, David Denyer, and Patrick Overy. 2016. “Sustainability‐oriented innovation: A systematic review.” International Journal of Management Reviews 18 (2): 180–205.

Arnold, Marlene Gabrielle, and Kay Hockerts. 2011. “The greening Dutchman: Phillips’ process of green flagging to drive sustainable innovation.” Business Strategy and the Environment 20 (6): 394–407.

Ayuso, Silvia, Miguel Ángel Rodríguez, and Joan Enric Ricart. 2006. “Using stakeholder dialogue as a source for new ideas: A dynamic capability underlying sustainable innovation.” Corporate Governance: International Journal of Business and Society 6 (4): 475–90.

Ayuso, Silvia, Miguel Ángel Rodríguez, Roberto García-Castro, and Miguel Ángel Ariño. 2011. “Does stakeholder engagement promote sustainable innovation orientation?” Industrial Management & Data Systems 11 (9): 1399–417.

Blowfield, Mick, Wayne Visser, and Finbarr Livesey. 2007. “Sustainability innovation: Mapping the territory.” University of Cambridge Programme for Industry Research Paper Series, n. 2.

Bocken, Nancy, and Samuel Short. 2015. “Towards a sufficiency-driven business model: Experiences and opportunities.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 18: 41–61.

Bocken, Nancy, Samuel Short, Padmaski Rana, and Steve Evans. 2013. “A value mapping tool for sustainable business modelling.” Corporate Governance: An International Review 13 (5): 482–97.

Bocken, Nancy, Samuel Short, Padmaski Rana, and Steve Evans. 2014. “A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes.” Journal of Cleaner Production 65: 42–56.

Boons, Frank, Carlos Montalvo, Jaco Quist, and Marcus Wagner. 2013. “Sustainable innovation, business models and economic performance: An overview.” Journal of Cleaner Production 45: 1–8.

Boons, Frank, and Florian Lüdeke-Freund. 2013. “Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda.” Journal of Cleaner Production 45: 1–8.

Boons, Frank, and Marcus Wagner. 2009. “Assessing the relationship between economic and ecological performance: Distinguishing system levels and the role of innovation.” Ecological Economics 68 (7): 1908–14.

Boons, Frank, Marian Chertow, Jooyoung Park, Wouter Spekkink, and Han Shi. 2016. “Industrial symbiosis dynamics and the problem of equivalence: Proposal for a comparative framework.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 21 (4): 938–52.

Bos-Brouwers, Hilke Elke Jake. 2010. “Corporate sustainability and innovation in SMEs: Evidence of themes and activities in practice.” Business Strategy and the Environment 19: 417–35.

Carrillo-Hermosilla, Javier, Pablo Del Río, and Totti Könnölä. 2010. “Diversity of eco-innovations: Reflections from selected case studies.” Journal of Cleaner Production 18: 1073–83.

Castiaux, Annick. 2012. “Developing dynamic capabilities to meet sustainable development challenges.” International Journal of Innovation Management 16 (6): 1240013.

Chen, Yu-Shan. 2008. “The driver of green innovation and green image—Green core competence.” Journal of Business Ethics 81 (3): 531–43.

Chen, Ping-Chuan, and Shiu Wan Hung. 2014. “Collaborative green innovation in emerging countries: A social capital perspective.” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 34 (3): 347–63.

Chertow, Marian, and John Ehrenfeld. 2012. “Organizing self-organizing systems: Toward a theory of industrial symbiosis.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 16: 13–27.

Clark, Garrette, Justin Kosoris, Long Nguyen Hong, and Marcel Crul. 2009. “Design for sustainability: Current trends in sustainable product design and development.” Sustainability 1 (3): 409–24.

Cooper, Harris, Larry V. Hedges, and Jeffrey C. Valentine. 2009. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Dacin, Peter A., Tina M. Dacin, and Margaret Matear. 2010. “Social entrepreneurship: Why we don’t need a new theory and how we move forward from here.” Academy of Management Perspectives 24: 37–57.

Dacin, M. Tina, Peter A. Dacin, and Paul Tracey. 2011. “Social entrepreneurship: A critique and future directions.” Organization Science 22: 1203–13.

Dangelico, Rosa Maria, and Devashish Pujari. 2010. “Mainstreaming green product innovation: Why and how companies integrate environmental sustainability.” Journal of Business Ethics 95 (3): 471–86.

De Marchi, Valentina. 2012. “Environmental innovation and R&D cooperation: Empirical evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms.” Research Policy 41 (3): 614–23.

Del Río, Pablo. 2009. “The empirical analysis of the determinants for environmental technological change: A research agenda.” Ecological Economics 68 (3): 861–78.

Del Río, Pablo, Javier Carrillo-Hermosilla, and Totti Könnölä. 2010. “Policy strategies to promote eco-innovation.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 14 (4): 541–57.

Di Domenico, Maria Laura, Helen Haugh, and Paul Tracey. 2010. “Social bricolage: Theorizing social value creation in social enterprises.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34: 681–703.

Ehrenfeld, John. 2005. “Eco-efficiency: Philosophy, theory and tools.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 9 (4): 6–8.

Elkington, John. 1997. Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Oxford: Capstone.

Figge, Frank, and Tobias Hahn. 2004. “Sustainable value added-measuring corporate contributions to sustainability beyond eco-efficiency.” Ecological Economics 48: 173–87.

Geels, Frank W. 2010. “Ontologies, socio-technical transitions (to sustainability), and the multi-level perspective.” Research Policy 39 (4): 495–510.

Geels, Frank W. 2011. “The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 1 (1): 24–40.

Geissdoefer, Martin, Paulo Saveget, Nancy Bocken, and Erik Jan Hultink. 2017. “The circular economy—A new sustainability paradigm?” Journal of Cleaner Production 143: 757–68.

Ghisseti, Claudia, Alberto Marzucchi, and Sandro Montresor. 2015. “The open eco-innovation model: An empirical investigation of eleven European countries.” Research Policy 44 (5): 1080–93.

Gladwin, Thomas N., James J. Kennelly, and Tara-Shelomith Krause. 1995. “Shifting paradigms for sustainable development: Implications for management theory and research.” Academy of Management Review 20 (4): 874–907.

Glänzel, Wolfgang. 2015. “Bibliometrics-aided retrieval: Where information retrieval meets scientometrics.” Scientometrics 102 (3): 2215–22.

Goodman, Jennifer, Angelina Korsunova, and Minna Halme. 2017. “Our collaborative future: Activities and roles of stakeholders in sustainability-oriented innovation.” Business Strategy and the environment 26 (6): 731–53.

Govindarajan, Vijay, and Ravi Ramamurti. 2011. “Reverse innovation, emerging markets, and global strategy.” Global Strategy Journal 1 (3–4): 191–205.

Hajikhani, Arash. 2017. “Emergence and dissemination of ecosystem concept in innovation studies: A systematic literature review study.” In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

Hall, Jeremy. 2002. “Sustainable development innovation; a research agenda for the next 10 years.” Journal of Cleaner Production 51: 277–88.

Hall, Jeremy. 2014. “Innovation and entrepreneurial dynamics in the base of the pyramid.” Technovation 34 (5–6): 265–269.

Halme, Minna, and Maria Korpela. 2014. “Responsible innovation toward sustainable development in small and medium-sized enterprises: A resource perspective.” Business Strategy and the Environment 23 (8): 547–66.

Hansen, Erik Gunnar, and Friedrich Grosse-Dunker. 2013. “Sustainable innovation.” In Encyclopedia of corporate social responsibility, edited by S. O. Idowu, N. Capaldi, and A. Das Gupta. New York and Heidelberg: Springer.

Hansen, Erik Gunnar, Friedrich Grosse-Dunker, and Ralf Reichwald. 2009. “Sustainability innovation cube—A framework to evaluate sustainability-oriented innovation.” International Journal of Innovation Management 13 (4): 683–713.

Hansen, Erik Gunnar, and Heiko Spitzeck. 2011. “Measuring the impacts of NGO partnerships: The corporate and societal benefits of community involvement.” Corporate Governance 11 (4): 415–26.

Harms, Dorli, Hansen, Erik Gunnar, and Stefan Schaltegger. 2013. “Strategies in sustainable supply chain management: An empirical investigation of large German companies.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 20 (4): 205–18.

Hart, Stuart L. 1995. “A natural-resource based view of the firm.” Academy of Management Review 20 (4): 986–1014.

Hart, Stuart L. 2012. “The third-generation corporation.” In Oxford handbook of business and the environment, edited by P. Bansal and A. J. Hoffman. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hart, Stuart L., and Clayton M. Christensen. 2002. “The great leap: Driving innovation from the base of the pyramid.” MIT Sloan Management Review 44: 51–56.

Hart, Stuart L., and Mark B. Milstein. 2003. “Creating sustainable value.” Academy of Management Executive 17 (2): 56–67.

Hellström, T. 2007. “Dimensions of environmentally sustainable innovation: The structure of eco-innovation concepts.” Sustainable Development 15 (3): 148–59.

Hockerts, Kay, and Wüstenhagen, R. 2010. “Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids—Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship.” Journal of Business Venturing 25 (5): 481–92.

Horbach, Jens. 2008. “Determinants of environmental innovation–New evidence from German panel data sources.” Research Policy 37 (1): 163–173.

Horbach, Jens, Christian Rammer, and Klaus Renning. 2012. “Determinants of eco-innovations by type of environmental impacts—The role of regulatory push/pull, technology push and market pull.” Ecological Economics 78: 112–22.

Inigo, Edurne, and Laura Albareda. 2016. “Understanding sustainable innovation as a complex adaptive system: A systemic approach to the firm.” Journal of Cleaner Production 126: 1–20.

Inigo, Edurne, Laura Albareda, and Paavo Ritala. 2017. “Business model innovation for sustainability: Exploring evolutionary and radical approaches through dynamic capabilities.” Industry and Innovation 24 (5): 515–42.

Jay, Jason, and Marine Gerard. 2015. “Accelerating the theory and practice of sustainability-oriented innovation.” MIT Sloan Research Paper No. 5148–15. Cambridge, MA: MIT Sloan School.

Kemp, Rene, Derk Loorbach, and Jan Rotmans. 2007. “Transition management as a model for managing processes of co-evolution.” International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology 14 (1): 78–91.

Klewitz, Johana, and Erik Gunnar Hansen. 2014. “Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: A systematic review.” Journal of Cleaner Production 65: 57–75.

Knutas, Anti, Arash Hajikhani, Juho Salminen, Jouni Ikonen, and Jari Porras. 2015. “Cloud-based bibliometric analysis service for systematic mapping studies.” Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Systems and Technologies 1008: 184–91. https://doi.org/10.1145/2812428.2812442.

Loorbach, Derk, Janneke Van Bakel, Gail Whiteman, and Jans Rotmans. 2010. “Business strategies for transitions towards sustainable systems.” Business Strategy and the Environment 19: 133–46.

McGowan, Katharine, and Francis Westley. 2015. “At the root of change: The history of social innovation.” In New frontiers in social innovation research, edited by A. Nicholls, J. Simon, M. Gabriel, and C. Whelan. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Melville, Nigel. 2010. “Information systems innovation for environmental sustainability.” MIS Quarterly 34 (1): 1–21.

Mirata, Murat, and Tareq Emtairah. 2005. “Industrial symbiosis networks and the contribution to environmental innovation—The case of the Landskrona industrial symbiosis programme.” Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (10–11): 993–1002.

Nicholls, Alex, and Alex Murdoch. 2012. “The nature of social innovation.” In Social innovation, edited by A. Nicholls and A. Murdoch. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nidumolu, Ram, Coimbatore Krishnarao Prahalad, and M. R. Rangaswami. 2009. “Why sustainability is now a key driver of innovation.” Harvard Business Review 87 (September): 57–64.

Nill, Jan, and Rene Kemp. 2009. “Evolutionary approaches for sustainable innovation policies: From niche to paradigm?” Research Policy 38 (4): 668–80.

Paquin, Raymond, and Jennifer Howard-Grenville. 2012. “The evolution of facilitated industrial symbiosis.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 16 (1): 83–93.

Porter, Michael E., and Class van der Linde. 1995. “Towards a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 9 (4): 97–118.

Porter, Michael E., and Mark Kramer. 2011. “Creating shared value.” Harvard Business Review 89 (½): 62–77.

Prahalad, Coimbatore Krishnarao. 2012. “Bottom of the pyramid as a source of breakthrough innovations.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 29 (1): 6–12.

Prahalad, Coimbatore Krishnarao, and Stuart L. Hart. 2001. “The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid.” Strategy and Business 26: 54–67.

Pujari, Devashish. 2006. “Eco-innovation and new product development: Understanding the influences on market performance.” Technovation 26 (1): 76–85.

Ranaei, Samira, Antti Knutas, Juho Salminen, and Arash Hajikhani. 2016. “Cloud-based patent and paper analysis tool for comparative analysis of research.” CompSysTech June: 315–22.

Rennings, Klaus. 2000. “Redefining innovation—Eco-innovation research and the contribution from ecological economics.” Ecological Economics 32 (2): 319–32.

Richter, Mario. 2013. “Business model innovation for sustainable energy: German utilities and renewable energy.” Energy Policy 62: 1226–37.

Schaltegger, Stefan, and Marcus Wagner. 2011. “Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions.” Business Strategy and the Environment 20 (4): 222–37.

Schaltegger, Stefan, and Roger Burritt. 2014. “Measuring and managing sustainability performance of supply chains.” Supply Chain Management 19 (3): 232–41.

Seebode, Dorothea, Sally Jeanrenaud, and John Bessant. 2012. “Managing innovation for sustainability.” R&D Management 42: 195–206.

Senge, Peter M., Brian Smith, Sara Schley, Joe Laur, and Nina Kruschwitz. 2008. The necessary revolution: How individuals and organizations are working together to create a sustainable world. New York: Doubleday.

Sharma, Arun, and Gopalkrishnan R. Iyer. 2012. “Resource-constrained product development: Implications for green marketing and green supply chains.” Industrial Marketing Management 41 (4): 599–608.

Sharma, Sanjay. 2005. “Through the lens of managerial interpretations: Stakeholder engagement, organizational knowledge and innovation.” In Corporate environmental strategy and competitive, edited by S. Sharma and A. Aragón-Correa. Northampton: Edward Elgar Academic.

Shrivastava, Paul. 1995. “Environmental technologies and competitive advantage.” Strategic Management Journal 16 (S1): 183–200.

Shrivastava, Paul, and Stuart L. Hart. 1995. “Creating sustainable corporations.” Business Strategy and the Environment 4: 154–65.

Small, Henry. 1973. “Cocitation in scientific literature—New measure of relationship between 2 documents.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 24 (4): 265–69.

Stubbs, Wendy, and Chris Cocklin. 2008. “Conceptualizing a sustainability business model.” Organization & Environment 21: 103–27.

Tukker, Arnold. 2005. “Leapfrogging into the future: Developing for sustainability.” International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development 1 (1–2): 65–84.

Tukker, Arnold, Martin Charter, Carlo Vezzoli, Eivind Sto, and Maj Much Andersen. 2008. System innovation for sustainability: Perspectives on radical changes to sustainable consumption and production. Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf.

Van Kleef, Jans A. G., and Nigel Roome. 2007. “Developing capabilities and competence for sustainable business management as innovation: A research agenda.” Journal of Cleaner Production 15 (1): 38–51.

Von Schomberg, Rene. 2013. “A vision of responsible innovation.” In Responsible innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, edited by R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz. Chichester: Wiley.

Wagner, Marcus. 2008. “Empirical influence of environmental management on innovation: Evidence from Europe.” Ecological Economics 66 (2–3): 392–402.

World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). 2000. Eco-efficiency: Creating more with less. Geneva: WBCSD.

World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). 1987. Our common future. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zollo, Maurizio, Carmelo Cennamo, and Kerstin Neumann. 2013. “Beyond what and why: Understanding organizational evolution towards sustainable enterprise models.” Organization & Environment 26 (3): 241–59.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Albareda, L., Hajikhani, A. (2019). Innovation for Sustainability: Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. In: Bocken, N., Ritala, P., Albareda, L., Verburg, R. (eds) Innovation for Sustainability. Palgrave Studies in Sustainable Business In Association with Future Earth. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97385-2_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97385-2_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-97384-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-97385-2

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)