Abstract

This chapter considers the factors that motivate narcissistic individuals to pursue external validation. Narcissistic individuals pursue external validation through various strategies (e.g., appearance enhancement, social media use), but we focus primarily on the desire for status because we believe it may be especially helpful for understanding the intrapsychic processes and interpersonal behaviors that characterize narcissistic individuals. We argue that the narcissistic concern for status may help us understand why the self-presentational goals of narcissistic individuals often focus on issues surrounding self-promotion or intimidation rather than affiliation. The lack of concern that narcissistic individuals have for affiliation suggests that their self-promotional efforts are not regulated by typical concerns about also being liked which may shed light on the reasons they engage in interpersonal behaviors that others tend to find irritating and aversive (e.g., being selfish or arrogant). We conclude by suggesting that the desire for status may be a fundamental aspect of narcissism that has the potential to provide additional insights into the cognitive processes and interpersonal behaviors that characterize narcissistic individuals rather than simply being one of the ways in which narcissistic individuals go about regulating their feelings of self-worth.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Grandiose narcissism refers to a set of personality traits and processes that are centered around an extremely positive – yet potentially fragile – self-concept (see Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001, for a review). The fragile nature of this grandiose self-concept is thought to lead individuals with narcissistic tendencies to pursue external validation in order to maintain their inflated self-perceptions (see Wallace, 2011, for a competing view of narcissistic self-enhancement). The external validation pursued by narcissistic individuals often takes the form of seeking the attention of others and attempting to improve their positions within their social groups. For example, narcissistic individuals try to capture the attention of others through a wide variety of strategies that include enhancing their appearance (e.g., Holtzman & Strube, 2010; Vazire, Naumann, Rentfrow, & Gosling, 2008), pursuing fame (e.g., Southard & Zeigler-Hill, 2016; Young & Pinsky, 2006), and strategically using social media (e.g., Buffardi & Campbell, 2008). Further, narcissistic individuals attempt to elevate their positions within their social environments through strategies such as bragging (Buss & Chiodo, 1991), displaying wealth and material goods (Piff, 2014; Sedikides, Gregg, Cisek, & Hart, 2007), affiliating with high-status individuals (Campbell, 1999), and pursuing leadership positions (Brunell et al., 2008; Grijalva, Harms, Newman, Gaddis, & Fraley, 2015). The purpose of the present chapter is to consider the factors that motivate narcissistic individuals to pursue external validation. We will focus primarily on the desire for status because we believe that this may be especially helpful for understanding the intrapsychic processes and interpersonal behaviors that characterize narcissistic individuals.

Status and Affiliation

The connections between personality processes and social behaviors have attracted a great deal of theoretical and empirical attention (e.g., Carson, 1969; Leary, 1957; Sullivan, 1953). Two basic dimensions have consistently emerged from research concerning social behavior such that the first dimension captures issues pertaining to status (i.e., the tendency to display power, mastery, and self-assertion rather than weakness, failure, and submission) and the second dimension captures affiliation (i.e., the tendency to engage in behaviors connected with intimacy, union, and solidarity rather than remoteness, hostility, and separation; Wiggins & Pincus, 1992). Status refers to a vertical or hierarchical form of social organization such that individuals with higher levels of status are able to influence the thoughts and behaviors of other individuals who possess lower levels of status (e.g., Anderson, Hildreth, & Howland, 2015; Blau, 1964). In contrast, affiliation captures a horizontal or nonhierarchical aspect of social organization that reflects the degree to which individuals are accepted and liked by others (e.g., Leary, Jongman-Sereno, & Diebels, 2014).

The basic idea that status and affiliation play vital roles in social behavior has been acknowledged by various theories across numerous disciplines (see Hogan & Blickle, in press, for a review). For example, the interpersonal circumplex (e.g., Leary, 1957; Wiggins, 1979) provides a comprehensive model of social behavior using the orthogonal axes of agency (status) and communion (affiliation). Adler (1939) referred to superiority striving (status) and social interest (affiliation). Hogan’s (1982) socioanalytic theory introduced the ideas of getting ahead (status) and getting along (affiliation). Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick (2008) proposed that social perceptions largely depend on competence (status) and warmth (affiliation). Wojciszke, Abele, and Baryla (2009) suggested that interpersonal attitudes largely consist of respect (status) and liking (affiliation). In evolutionary psychology, Buss (2015) has argued for the importance of navigating status hierarchies (status) as well as forming coalitions and alliances (affiliation). In anthropology, Redfield (1960) observed that social groups depend on members getting a living (status) and living together (affiliation). In sociology, Parsons and Bales (1955) argued that human groups depend on the completion of tasks related to group survival (status) and socio-emotional tasks (affiliation). McAdams (1988) found that the stories people develop about their own identities center around two basic themes that he referred to as power (status) and intimacy (affiliation). Foa and Foa (1980) developed social exchange theory, which argues that the exchange of status (status) and love (affiliation) is at the core of all social interactions. Taken together, these various theoretical approaches suggest that issues pertaining to status and affiliation play central roles in guiding human social behavior.

Although status and affiliation appear to be fundamental social motives (e.g., Anderson et al., 2015; Baumeister & Leary, 1995), individuals may still differ in the degree to which they emphasize the pursuit of status and affiliation in their own lives (e.g., Neel, Kenrick, White, & Neuberg, 2016). For example, some individuals may be more concerned with status than they are with affiliation. Although status and affiliation are often correlated such that individuals with higher levels of status are often liked by others (Anderson et al., 2015), this is not always the case (e.g., an individual can be liked but have low status within a group). In fact, there is sometimes a trade-off between status and affiliation such that it may be difficult for an individual to completely satisfy both of these motivations simultaneously (e.g., Cuddy et al., 2008; Hogan & Blickle, in press). For example, a business owner who behaves in a highly professional manner when interacting with his/her employees may be respected and admired by his/her employees (high status), but she may not be especially liked by them (low affiliation). In contrast, a new employee who desperately tries to befriend his co-workers may be well liked by them (high affiliation), but he/she may fail to earn their respect (low status). Individuals with narcissistic personality features tend to resolve the potential trade-off between status and affiliation by focusing their efforts on the attainment of status and demonstrating relatively little concern about affiliation (e.g., Campbell, 1999; Campbell, Rudich, & Sedikides, 2002; Raskin & Novacek, 1991; Raskin, Novacek, & Hogan, 1991a, 1991b). To put it another way, narcissistic individuals tend to care a great deal about climbing the status hierarchy, but they are not terribly concerned about whether people like them.

The Desire for Status

Status hierarchies are pervasive across human social groups due, at least in part, to the benefits these hierarchies provide for both individuals and the larger social groups to which they belong (see Anderson et al., 2015, for a review). For example, hierarchical social structures are relatively easy for individuals to understand (Zitek & Tiedens, 2012), and groups tend to perform better on tasks requiring cooperation when they have a hierarchical structure (Halevy, Chou, Galinsky, & Murnighan, 2012). However, it is important to recognize that status hierarchies do not benefit everyone equally. Rather, this sort of vertical social structure tends to provide far more advantages for individuals near the top of the hierarchy than it does for individuals closer to the bottom (Magee & Galinsky, 2008). As a result, it seems likely that individuals with high levels of status would have experienced considerable survival and reproductive benefits throughout the course of human evolution (e.g., greater access to scarce resources, heightened attractiveness as a potential mate; Barkow, 1975; Buss, 2008; Ellis, 1995; Henrich & Gil-White, 2001; see Anderson et al., 2015, for a review).

The concern that narcissistic individuals display regarding their status may explain why their self-presentational goals often focus on self-promotion (being perceived as competent) or intimidation (being perceived as a potential threat) rather than ingratiation (being perceived as likeable; Leary, Bednarski, Hammon, & Duncan, 1997). This lack of concern for affiliation means that the self-promotional efforts of narcissistic individuals are not held in check by typical concerns about also being liked which may help explain why they engage in various behaviors that others tend to find irritating and aversive (e.g., being selfish or arrogant; Leary et al., 2014; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). Further, this indifference to affiliation may also contribute to narcissistic individuals having difficulty maintaining positive relationships with others despite their initial charm and attractiveness as interaction partners (e.g., Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2010; Paulhus, 1998). The fact that narcissistic individuals enter social situations with the goal of gaining status rather than being liked may help us understand many of their self-defeating interpersonal behaviors. That is, the interpersonal strategies that narcissistic individuals employ (e.g., frequent self-promotion) are intended to elicit the respect and admiration of others, but these strategies are often unsuccessful because they tend to unintentionally alienate and frustrate those individuals who could actually grant them status (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). This cycle of paradoxical and counterproductive interpersonal behaviors results in narcissistic individuals having a great deal of difficulty achieving and maintaining the level of status they crave so desperately.

The strong desire for status that characterizes narcissistic individuals can be observed through various aspects of their behavior including their self-reported desires (Bradlee & Emmons, 1992; Zeigler-Hill et al., 2017), responses to projective tests (Carroll, 1987), fantasies (Raskin & Novacek, 1991), and descriptions of sexual behavior (Foster, Shrira, & Campbell, 2006). This desire for status is so intense that it seems to shape much of their social lives. For example, narcissistic individuals are far more likely than other individuals to engage in the self-serving bias (e.g., take credit for success and blame others for failure) even when they are working with close others (Campbell, Reeder, Sedikides, & Elliot, 2000). The desire for status also has implications for the romantic lives of narcissistic individuals by leading them to select partners who are likely to enhance their status (Campbell, 1999) and employ a game-playing romantic style (Campbell, Foster, & Finkel, 2002). Taken together, these results suggest that narcissistic individuals try to use their relationships to elevate their own social position rather than being concerned about developing truly intimate connections with other people.

In addition to showing a strong desire to elevate their own positions within their social groups, narcissistic individuals tend to show support for hierarchical structures in general (Zitek & Jordan, 2016). This support for hierarchical structures is consistent with the observation that individuals who are near the top of the hierarchy – or who believe they will soon be near the top of the hierarchy – are more likely to favor hierarchical structures (Lee, Pratto, & Johnson, 2011). Even if narcissistic individuals are not currently near the top of status hierarchy, their overly positive self-views may lead them to believe that they will soon ascend the status hierarchy. For example, narcissistic individuals believe they are more intelligent and attractive than others (Gabriel, Critelli, & Ee, 1994), inflate their self-ratings of their own performance (John & Robins, 1994), tend to be overconfident (Campbell, Goodie, & Foster, 2004), make overly optimistic predictions for their future performance (Farwell & Wohlwend-Lloyd, 1998), and believe they are unique and special (Emmons, 1984). The overly positive self-views that are held by narcissistic individuals tend to be focused on agentic qualities and domains that are relevant to the acquisition of status (e.g., Campbell, Rudich, et al., 2002). Zitek and Jordan (2016) provide a compelling argument that narcissistic individuals may show such strong support for hierarchical structures for the simple reason that they think doing so will be beneficial for them (i.e., they are either already toward the top of the hierarchy or believe they will be at some point in the future ).

The Pursuit of Status

Despite the fact that hierarchical structures are ubiquitous in human social groups, we have a relatively limited understanding of these systems. For example, there is still a great deal of debate concerning how individuals go about the task of navigating social hierarchies. There are two competing perspectives regarding the strategies that individuals employ to pursue status (Anderson, Srivastava, Beer, Spataro, & Chatman, 2006; Cheng, Tracy, Foulsham, Kindstone, & Henrich, 2013). One perspective argues that conflict is instrumental to the navigation of social hierarchies with individuals utilizing coercive tactics (e.g., intimidation, aggression) and manipulation in order to improve their status and gain influence over others (Buss & Duntley, 2006; Griskevicius et al., 2009; Mazur, 1973). The second perspective focuses on issues surrounding competence and argues that individuals who have instrumental value (e.g., possess useful skills, characteristics, abilities, or knowledge) will be granted status by others (Anderson et al., 2015; Berger, Cohen, & Zelditch, 1972; Blau, 1964; Fiske, 2010; Goldhamer & Shils, 1939; Magee & Galinsky, 2008). Henrich and his colleagues (e.g., Cheng et al., 2013; Cheng, Tracy, & Henrich, 2010; Henrich & Gil-White, 2001) developed the dominance-prestige model in an attempt to integrate the conflict-based and competence-based perspectives concerning status. This model suggests that both perspectives capture strategies that individuals may use for navigating status hierarchies. That is, according to the dominance-prestige model, there are two distinct pathways for gaining status in social groups: dominance-based strategies and prestige-based strategies . Dominance-based strategies are conflict-oriented because they involve the use of intimidation, coercion, aggression, and the induction of fear to influence status. In contrast, prestige-based strategies are competence-oriented because they involve individuals being granted status following demonstrations of their desirable skills and proficiencies (i.e., displaying their instrumental value). This model argues that humans have relied on dominance-based strategies throughout most of our evolutionary history but that we have more recently come to also value prestige-based strategies (see Henrich & Gil-White, 2001, for an extended discussion).

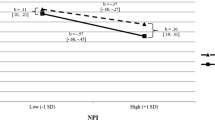

Grandiose narcissism has been shown to be linked with dominance-based and prestige -based strategies for attaining status. For example, Zeigler-Hill et al. (2017) found that both narcissistic admiration (assertive self-enhancement and self-promotion) and narcissistic rivalry (antagonistic self-protection and self-defense) from the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Concept model (Back et al., 2013) were positively associated with the use of dominance-based strategies for gaining status. However, these two facets of grandiose narcissism had opposing associations with prestige-based strategies such that narcissistic admiration was positively associated with this approach to attaining status, whereas narcissistic rivalry was negatively associated with this approach. Additional research is necessary to gain a clearer and more nuanced understanding of the connections that different conceptualizations of narcissism have with these strategies for pursuing status. For example, are there additional moderators that play a role in whether narcissistic individuals decide to employ dominance-based strategies in their pursuit of status (e.g., being physically larger or stronger than potential rivals, already having greater control over valuable resources)? In addition, it would be helpful to develop a better understanding of the consequences that narcissistic individuals experience when they are successful – or unsuccessful – in their attempts to attain status. For example, Zeigler-Hill et al. (2017) found that the state self-esteem of individuals with high levels of narcissistic admiration is particularly responsive to their perceived level of status such that they report especially high levels of state self-esteem on days when they perceive others as respecting and admiring them. This pattern is consistent with recent work suggesting that one function of self-esteem may be to serve as a hierometer by tracking current levels of status (Mahadevan, Gregg, Sedikides, & De Waal-Andrews, 2016).

Conclusion

In summary, narcissistic individuals have an especially strong desire for status, demonstrate support for the existence of status hierarchies, view themselves as having status or believe that they will have status in the future, and are willing to engage in various strategies to attain status. Despite this desire for status, narcissism has complex associations with the attainment of status because some narcissistic qualities promote status attainment (e.g., self-confidence), whereas other narcissistic qualities hinder – or even completely undermine – the attainment of status (e.g., selfishness, the tendency to be increasingly disliked by others over time). This has led to a view of narcissism as being something akin to a “mixed blessing” in terms of status attainment (e.g., Anderson & Cowan, 2014; Cheng et al., 2010; Paulhus ,1998; Paunonen, Lönnqvist, Verkasalo, Leikas, & Nissinen, 2006).

Although recent research has shown that narcissistic individuals are willing to employ a variety of strategies to pursue status (e.g., Zeigler-Hill et al., 2017), it would be helpful for future studies to examine the conditions under which narcissistic individuals prefer to employ specific strategies. For example, it is possible that narcissistic individuals show a general preference for utilizing prestige-based strategies and are only likely to resort to dominance-based strategies when they are unsuccessful in their efforts to gain prestige . However, it is also possible that narcissistic individuals actually enjoy exerting their power over others by using dominance-based strategies. In addition, future research concerning the interplay between narcissism, status, and self-esteem may help resolve the inconsistent results that have emerged concerning the fragile nature of narcissistic self-esteem (e.g., Bosson et al., 2008; see Southard, Vrabel, McCabe, & Zeigler-Hill, this volume, for a review). This direction for future research is potentially important because Leary et al. (2014) argue that status provides a less consistent sense of value across situations than is the case for affiliation. This suggests the intriguing possibility that the tendency for narcissistic individuals to care more about gaining respect and admiration than being liked by others may contribute to their constant need for external validation and heightened reactivity to negative events. That is, narcissistic individuals appear to pursue status in order to affirm their value, but their extreme focus on status may paradoxically create an escalating pattern in which their increasingly desperate pursuit of status makes it even more difficult for them to feel a lasting sense of being valuable. We believe the desire for status may be a fundamental aspect of narcissism that has the potential to shed light on some of the intrapsychic processes and interpersonal behaviors that characterize narcissistic individuals rather than simply being one of the ways in which narcissistic individuals go about regulating their feelings of self-worth.

References

Adler, A. (1939). Social interest. New York: Plenum.

Anderson, C., & Cowan, J. (2014). Personality and status attainment: A micropolitics perspective. In J. T. Cheng, J. L. Tracy, & C. Anderson (Eds.), The psychology of social status (pp. 99–117). New York: Springer.

Anderson, C., Hildreth, J. A. D., & Howland, L. (2015). Is the desire for status a fundamental human motive? A review of the empirical literature. Psychological Bulletin, 141, 574–601.

Anderson, C., Srivastava, S., Beer, J. S., Spataro, S. E., & Chatman, J. A. (2006). Knowing your place: Self-perceptions of status in face-to-face groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 1094–1110.

Back, M. D., Küfner, A. C. P., Dufner, M., Gerlach, T. M., Rauthmann, J. F., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2013). Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: Disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 1013–1037.

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2010). Why are narcissists so charming at first sight? Decoding the narcissism-popularity link at zero acquaintance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 132–145.

Barkow, J. H. (1975). Prestige and culture: A biosocial interpretation. Current Anthropology, 16, 553–572.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

Berger, J., Cohen, B. P., & Zelditch, M. (1972). Status characteristics and social interaction. American Sociological Review, 37, 241–255.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: Wiley.

Bosson, J. K., Lakey, C. E., Campbell, W. K., Zeigler-Hill, V., Jordan, C. H., & Kernis, M. H. (2008). Untangling the links between narcissism and self-esteem: A theoretical and empirical review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 1415–1439.

Bradlee, P. M., & Emmons, R. A. (1992). Locating narcissism within the interpersonal circumplex and the five-factor model. Personality and Individual Differences, 13, 821–830.

Brunell, A. B., Gentry, W. A., Campbell, W. K., Hoffman, B. J., Kuhnert, K. W., & DeMarree, K. G. (2008). Leader emergence: The case of the narcissistic leader. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1663–1676.

Buffardi, L. E., & Campbell, W. K. (2008). Narcissism and social networking web sites. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1303–1314.

Buss, D. M. (2008). Human nature and individual differences. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 29–60). New York: Guilford Press.

Buss, D. M. (2015). Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind (5th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Buss, D. M., & Chiodo, L. M. (1991). Narcissistic acts in everyday life. Journal of Personality, 59, 179–215.

Buss, D. M., & Duntley, J. D. (2006). The evolution of aggression. In M. Schaller, D. T. Kenrick, & J. A. Simpson (Eds.), Evolution and social psychology (pp. 263–286). New York: Psychology Press.

Campbell, W. K. (1999). Narcissism and romantic attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1254–1270.

Campbell, W. K., Foster, C. A., & Finkel, E. J. (2002). Does self-love lead to love for others? A story of narcissistic game playing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 340–354.

Campbell, W. K., Goodie, A. S., & Foster, J. D. (2004). Narcissism, confidence, and risk attitude. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 17, 297–311.

Campbell, W. K., Reeder, G. D., Sedikides, C., & Elliot, A. J. (2000). Narcissism and comparative self-enhancement strategies. Journal of Research in Personality, 34, 329–347.

Campbell, W. K., Rudich, E. A., & Sedikides, C. (2002). Narcissism, self-esteem, and the positivity of self-views: Two portraits of self-love. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 358–368.

Carroll, L. (1987). A study of narcissism, affiliation, intimacy, and power motives among students in business administration. Psychological Reports, 61, 355–358.

Carson, R. C. (1969). Interaction concepts of personality. Chicago: Aldine.

Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Foulsham, T., Kindstone, A., & Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: Evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 103–125.

Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., & Henrich, J. (2010). Pride, personality, and the evolutionary foundations of human social status. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31, 334–347.

Cuddy, A. J., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 61–149.

Ellis, B. J. (1995). The evolution of sexual attraction: Evaluative mechanisms in women. In J. H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.), The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture (pp. 267–288). New York: Oxford University Press.

Emmons, R. A. (1984). Factor analysis and construct validity of the narcissistic personality inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48, 291–300.

Farwell, L., & Wohlwend-Lloyd, R. (1998). Narcissistic processes: Optimistic expectations, favorable self-evaluations, and self-enhancing opportunities. Journal of Personality, 66, 65–83.

Fiske, S. T. (2010). Interpersonal stratification: Status, power, and subordination. In S. T. Fiske, G. Lindzey, & D. T. Gilbert (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., pp. 941–982). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Foa, E. B., & Foa, U. G. (1980). Resource theory of social exchange. In J. W. Thibaut, J. T. Spence, & R. C. Carson (Eds.), Contemporary topics in social psychology (pp. 99–131). Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press.

Foster, J. D., Shrira, I., & Campbell, W. K. (2006). Theoretical models of narcissism, sexuality, and relationship commitment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 23, 367–386.

Gabriel, M. T., Critelli, J. W., & Ee, J. S. (1994). Narcissistic illusions in self-evaluations of intelligence and attractiveness. Journal of Personality, 62, 143–155.

Goldhamer, H., & Shils, E. A. (1939). Types of power and status. American Journal of Sociology, 45, 171–182.

Grijalva, E., Harms, P. D., Newman, D. A., Gaddis, B. H., & Fraley, R. C. (2015). Narcissism and leadership: A meta-analytic review of linear and nonlinear relationships. Personnel Psychology, 68, 1–47.

Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., Gangestad, S. W., Perea, E. F., Shapiro, J. R., & Kenrick, D. T. (2009). Aggress to impress: Hostility as an evolved context-dependent strategy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 980–994.

Halevy, N., Chou, E. Y., Galinsky, A. D., & Murnighan, J. K. (2012). When hierarchy wins: Evidence from the National Basketball Association. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 398–406.

Henrich, J., & Gil-White, F. J. (2001). The evolution of prestige: Freely conferred deference as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evolution and Human Behavior, 22, 165–196.

Hogan, R. (1982). A socioanalytic theory of personality. In M. M. Page (Ed.), Personality: Current theory and research (pp. 55–89). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Hogan, R., & Blickle, G. (in press). Socioanalytic theory: Basic concepts, supporting evidence, and practical implications. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of personality and individual differences. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Holtzman, N. S., & Strube, M. J. (2010). Narcissism and attractiveness. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 133–136.

John, O. P., & Robins, R. W. (1994). Accuracy and bias in self-perception: Individual differences in self-enhancement and the role of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 206–219.

Leary, M. R., Bednarski, R., Hammon, D., & Duncan, T. (1997). Blowhards, snobs, and narcissists: Interpersonal reactions to excessive egoism. In R. M. Kowalski (Ed.), Behaving badly: Aversive behaviors in interpersonal relationships (pp. 111–131). New York: Plenum.

Leary, M. R., Jongman-Sereno, K. P., & Diebels, K. J. (2014). The pursuit of status: A self-presentational perspective on the quest for social value. In J. T. Cheng, J. L. Tracy, & C. Anderson (Eds.), The psychology of social status (pp. 159–178). New York: Springer.

Leary, T. F. (1957). Interpersonal diagnosis of personality: A functional theory and methodology for personality evaluation. New York: Ronald.

Lee, I. C., Pratto, F., & Johnson, B. T. (2011). Intergroup consensus/disagreement in support of group-based hierarchy: An examination of socio-structural and psycho-cultural factors. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 1029–1064.

Magee, J. C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Social hierarchy: The self-reinforcing nature of power and status. Academy of Management Annals, 2, 351–398.

Mahadevan, N., Gregg, A. P., Sedikides, C., & De Waal-Andrews, W. G. (2016). Winners, losers, insiders, and outsiders: Comparing hierometer and sociometer theories of self-regard. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 334.

Mazur, A. (1973). A cross-species comparison of status in small established groups. American Sociological Review, 38, 513–530.

McAdams, D. P. (1988). Power, intimacy, and the life story. New York: Guilford.

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12, 177–196.

Neel, R., Kenrick, D. T., White, A. E., & Neuberg, S. L. (2016). Individual differences in fundamental social motives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110, 887–907.

Parsons, T., & Bales, R. F. (1955). Family, socialization and interaction process. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Paulhus, D. L. (1998). Interpersonal and intrapsychic adaptiveness of trait self-enhancement: A mixed blessing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1197–1208.

Paunonen, S. V., Lönnqvist, J. E., Verkasalo, M., Leikas, S., & Nissinen, V. (2006). Narcissism and emergent leadership in military cadets. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 475–486.

Piff, P. K. (2014). Wealth and the inflated self: Class, entitlement, and narcissism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 34–43.

Raskin, R., & Novacek, J. (1991). Narcissism and the use of fantasy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47, 490–499.

Raskin, R., Novacek, J., & Hogan, R. (1991a). Narcissism, self-esteem, and defensive self-enhancement. Journal of Personality, 59, 20–38.

Raskin, R., Novacek, J., & Hogan, R. (1991b). Narcissistic self-esteem management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 911–918.

Redfield, R. (1960). How society operates. In H. L. Shapiro (Ed.), Man, culture, and society (pp. 345–368). New York: Oxford University Press.

Sedikides, C., Gregg, A. P., Cisek, S., & Hart, C. M. (2007). The I that buys: Narcissists as consumers. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 254–257.

Southard, A. C., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2016). The dark triad and fame interest: Do dark personalities desire stardom? Current Psychology, 35, 255–267.

Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton.

Vazire, S., Naumann, L. P., Rentfrow, P. J., & Gosling, S. D. (2008). Portrait of a narcissist: Manifestations of narcissism in physical appearance. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 1439–1447.

Wallace, H. M. (2011). Narcissistic self-enhancement. In W. K. Campbell & J. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatment (pp. 309–318). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Wiggins, J. S. (1979). A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 395–412.

Wiggins, J. S., & Pincus, A. L. (1992). Personality: Structure and assessment. Annual Review of Psychology, 43, 473–504.

Wojciszke, B., Abele, A. E., & Baryla, W. (2009). Two dimensions of interpersonal attitudes: Liking depends on communion, respect depends on agency. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 973–990.

Young, S. M., & Pinsky, D. (2006). Narcissism and celebrity. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 463–471.

Zeigler-Hill, V., Vrabel, J.K., Cosby, C.A., Traeder, C.K., McCabe, G.A., & Hobbs, K.A. (2017). Narcissism and the desire for status. Manuscript in preparation.

Zitek, E. M., & Jordan, A. H. (2016). Narcissism predicts support for hierarchy (at least when narcissists think they can rise to the top). Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7, 707–716.

Zitek, E. M., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2012). The fluency of social hierarchy: The ease with which hierarchical relationships are seen, remembered, learned, and liked. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 98–115.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Zeigler-Hill, V., McCabe, G.A., Vrabel, J.K., Raby, C.M., Cronin, S. (2018). The Narcissistic Pursuit of Status. In: Hermann, A., Brunell, A., Foster, J. (eds) Handbook of Trait Narcissism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_32

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_32

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-92170-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-92171-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)