Abstract

This paper discusses the distribution of wealth along with the phenomenal changes in wealth inequality worldwide; focusing, however, on Great Britain over the previous decade. By making use of the Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS), put together in Great Britain in waves from July 2006 to June 2014, we identify the main outcomes of the wealth distribution across time and space, i.e. the government office regions of the country. In our empirical analysis, we use house prices across the regions of Great Britain to identify their effect on the evolution of wealth inequality. Our results confirm that property wealth, and hence house prices, significantly affect inequality across the different groups of the wealth distribution. Moreover, among other findings, wealth is increasingly owned by those who can afford to buy real properties, while those who cannot, they observe their wealth decreasing sharply. Models have been tested for robustness across several specifications.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

JEL Classification

1 Introduction

We live in a world that has been growing increasingly unequal. It is a fact that, over the last century, the rich became richer and the poor became poorer. Over the last 30 years, the gap between rich and poor has reached its highest levels on record in most countries. In fact, 10% of the population worldwide earn almost 9.6 times more than the income of the bottom 10% (OECD 2015, p. 15). Back in 2011, this ratio was 9 times, something that shows the very fast pace in terms of the gap increase (OECD 2011). Similar results from a previous publication of OECD (2008) show that wealth was more unequally distributed than income, with some countries having low income inequality but high wealth inequality . Nowadays, according to the latest findings, wealth is more concentrated than income: on average, the top 10% share of the wealthiest households receive almost 25% of the income while they hold half of total wealth Footnote 1; the next 50% of the households hold almost the other half, while the bottom 10% of households own about 3% of total wealth. This unprecedented level of wealth concentration towards the high end of the distribution has also been shown to have considerable economic effects including lower potential economic growth (OECD 2015).

As discussed in the literature, and as we will observe in this chapter, the increasing income and wealth inequality worldwide has increased economists’ interest to investigate income and wealth distributions with a special focus on the recent growth at the top tails of both distributions (Piketty 2014; Benhabib et al. 2017).

Inequality (of both income and wealth) has become an increasing universal concern among economists, policymakers and citizens. The reasons behind this phenomenon have been under debate for a long time and it seems probable that it will continue to be an ongoing topic in future. This study aims to examine whether house price evolution in Great Britain over the last decade has played any role in changing household wealth distribution, contributing somehow to the increase in wealth inequality among households. Moreover, our scope also focuses on the geographical allocation of net aggregate and property wealth, in particular, across the several government office regions of GB in order to observe the wealth concentration patterns of the different household groups.

In the next sections, we build a theoretical framework drawing on the extensive international literature on wealth. In particular, we discuss, its constituents, the factors that affect wealth along with its effects on households, the well-documented term of ‘wealth inequality ’ and the evolution of wealth inequality both globally and focusing on GB. For the purposes of our empirical analysis, data on household wealth for GB had been very limited. It is only after July 2006 that sufficient household wealth information has been effectively collected by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) through the Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS) .Footnote 2 It is important to mention at this point that at the time our analysis was undertaken, data of wave 5 from latest WAS concerning the period July 2014–June 2016 were not yet released, while just before our submission, the report of the main findings of this wave was published. Therefore, most of our analysis is based on the earlier trends while some of our figures incorporate the most recent data and refer to the latest report released by ONS. Our empirical analysis includes data of the first four waves available covering data on household wealth from July 2006 to June 2014. After discussing the distribution of wealth across GB in Sect. 3, we provide some empirical evidence to show that house prices significantly affect wealth distribution in the country. Next, we present an extensive discussion of whether the changes in house prices have played any role to the increase in wealth inequality across the different government office regions of the country. Finally, we summarise and conclude.

Our results suggest that house ownership in most regions with the highest levels of productivity (such as London and South East) correlates to higher wealth but also shows a very strong relationship with how wealth is developing over time. House prices grew the fastest in regions where wealth was the highest to begin with. Notably these are also the most productive locations of the country and offer the highest per capita income. It is difficult to infer causality from these trends, thus our analysis should be treated as descriptive on this score. Nevertheless, we document that the trend for wealth to be increasingly concentrated amongst the richest is not only occurring for the overall distribution of households but also has very distinctive spatial patterns. The pattern appears to be dictated by house prices .

2 Literature Review

Our paper has been motivated by a pioneering work of Kuhn et al. (2017), which uses a dataset of Historical Survey of Consumer Finances (HSCF) with detailed household-level information across the US over seven decades (1949–2013) to observe income and wealth distributions. Their findings show, among others, that there is significant widening of income and wealth disparities in the US since World War II, identifying trends among different groups across the decades. The reason for these disparities is due to the heterogeneity of household portfolios across the wealth distribution. Interestingly, household portfolios systematically vary across the distribution. More specifically, stock and house price changes have differential effects on the top and the middle of the distribution. As highlighted, the portfolios of the wealthy households primarily include business equity and financial assets . On the other hand, the household portfolios of the typical middle class consist of highly concentrated and highly leveraged residential real assets . As a result of that, the increasing house prices cause significant wealth gains to the middle-class households. Finally, higher equity prices lead to substantial wealth increases in the richest households (Kuhn et al. 2017).

Roine and Waldenström (2015) in reviewing the long-run trends of income and wealth distributions found that inequality was at historically high levels almost everywhere towards the beginning of last century. During the first 80 years, wealth inequality decreased worldwide mainly because of the falling wealth concentration and the decreasing incomes of the top shares of the distribution. Since then, trends across countries for income and wealth distributions have been significantly differentiated, while, in periods of high growth , top shares also increase, whereas lower top shares are related to high marginal tax rates and even democracy.

As Campanella (2017, December 8) shows, there is a clear distinction between developing and developed economies . More specifically, in developing economies , over the past three decades of globalisation , we observed the creation of a booming socio-economic layer, the urban middle class , which further expanded the gap between cities and rural regions. However, in advanced economies, the combination of globalisation and technological progress has generated significant advantages to a small minority of highly qualified professionals, which adversely, squeezed the middle class . In these latter cases, the living standards for the middle and the bottom of the income scale have stagnated, due to the available cheaper labour abroad and the inadequate redistributive policies in home countries.

To begin with, it is essential to draw some distinctive lines between some significant concepts on this theme, such these of income, assets , debt and wealth (according to how they were defined by Kuhn et al. 2017).

-

Income is regarded as the total sum of wages and salaries (including any professional practice, self-employment, rents, dividends, interests, transfer payments and business income).

-

Assets consist of the following: liquid assets (checking accounts, savings, money market accounts and deposits), bonds, equity, cash value of life insurances, cars, business bonds, but also housing and other real estate.

-

Debt is divided into housing (on owner-occupied houses and other property assets ) and non-housing (car loans, education loans and loans on other consumer durables). Indebtedness is the other side of wealth. On average, almost half of the population of OECD countries is in debt (OECD 2011).

-

Wealth constitutes the households’ net worth, i.e. total assets minus total debt (Kuhn et al. 2017).

Wealth constitutes a significant component of household economic well-being since their access to resources can be affected by their stock of wealth. Nevertheless, due to scarcity of data on wealth and its distribution, studies often use data on households’ income to track and monitor their economic well-being. In order to conceive the economic conditions and the households’ well-being, it is important to investigate it “further than a simple measure of income” (ONS 2015a, p. 2) highlighting in this way the importance of the in-depth analysis of the household wealth distribution when examining national well-being. As explained by ONS (2015a, p. 2), “the increase in home ownership, the move from traditional roles and working patterns, a higher proportion of the population now owning shares and contributing to investment schemes as well as the accumulation of wealth over the life cycle, particularly through pension participation, have all contributed to the changing composition of wealth”.

Davies and Shorrocks (2000), when studying the distribution of personal wealth, specified that it refers to the material assets (in the form of real properties and financial claims) that can be purchased to the marketplace; however, some studies on wealth include pension rights. Therefore, they regard wealth as the ‘net worth’ of the non-human capital, that is assets minus debts. One of their major findings is that wealth is more unequal than income, while they have indicated an overall long-term decreasing trend in wealth inequality over the previous century. As discussed in their paper, possible reasons of wealth discrepancies constitute the lifecycle accumulation and the inheritance especially at the top-end share of the distribution.

As mentioned above, household’s wealth is an important indicator of well-being and lifestyle. Households can maintain their living standards when income drops either unexpectedly due to unemployment or expectedly due to retirement or other causes, if there is enough wealth of an accessible form (or if there is access to borrowing). In addition to this, Crawford et al. (2016) pointed another aspect of wealth, which is that it can influence not only their owners’ life style, but also their descendants’ lives as wealth,Footnote 3 in contrast with income, could be bequeathed to the next generations.

Another pioneering study with interesting findings on the evolution of wealth and its trends on household level in the US comes from Wolff (2017), who examined the period between 1962 and 2016, focusing on the middle class . Wolff used mainly the Survey on Consumer Finances (SCF) and indicated that over the last decade asset prices in the US sank between 2007 and 2010 while later they recovered. At the same time, median wealth dropped dramatically by 44%, while in terms of inequality of the net worth increased sharply. As discussed, the steep drop of the median wealth and the simultaneous increase in the overall net worth inequality is obviously arising from the high household leverage of the middle class and the very high share of houses as part of their wealth. Although mean wealth exceeded its previous highest during 2007, median wealth was persistently lower in 2016 by 34%. The author indicated that more than 100% of the rebound in both measurements was due to high capital gains on wealth.Footnote 4 However, this was counterbalanced by negative household savings. As for other liabilities, which kept on dropping for the middle households between 2010 and 2016, wealth inequality in the US increased (Wolff 2017).

Although income and wealth are two concepts closely linked, and therefore, the observed income inequality across many countries has direct effects on wealth inequality ; the observation and the analysis of income and hence, of income inequality , is outside the scope of this chapter. However, the literature and the findings on income inequality are more extensive than those of wealth inequality ; and this is due to data unavailability or at best a scarcity of data on wealth. On this relationship between income and wealth, Aiyagari (1994) and more recently Benhabib et al. (2017), among others, specify that in economies where concentration of wealth is mainly led by stochastic earnings,Footnote 5 there is a clear, positive relationship between income and wealth inequality . This is because higher earning risks would increase wealth concentration through precautionary savings, and therefore, under particular borrowing constraints this would end up to an increase in wealth inequality .

Another reason why wealth distribution is more difficult to be measured in comparison with income is that part of wealth is hidden by the so-called tax havens which makes the overall analysis of wealth with precision difficult. Alstadsaeter et al. (2017) in their paper estimated the household wealth owned by citizens of each country in offshore tax havens . From their findings, almost 10% of the global GDP is kept in tax havens around the world while for the UK in particular, citizens/residents have 16–17% of wealth hidden in tax havens . As the authors mention, “Offshore wealth has a larger effect on inequality in the UK” (Alstadsaeter et al. 2017, p. 3). Moreover, they discussed that in all countries, when accounting for the offshore wealth, inequality increased significantly compared to the tax data analyses observed. Therefore, from the above, the results on wealth inequality coming from studies that do not consider offshore wealth to tax heavens provide underestimation of the actual wealth inequality . Two fundamental outcomes of this paper are: (a) inequality significantly decreased in Western World during the first half of the previous century, and (b) it has sharply increased since 1980s especially in the US. The main driver behind the drop in inequality at the beginning of last century came from the interactions of multiple losses of wealth by the richest. As explained, both World Wars, the Great Depression of 1930s along with several policies against capital, such as imposing capital taxation, notably high rates of inheritance tax, nationalisations and rent controls, all decreased the significance of wealth and the accumulation of capital (Piketty and Zucman 2014). Later, over the last decades, the reason why wealth inequality has increased is due to the fast wealth concentration to the top income shares (Saez and Zucman 2016).

A number of studies have focused on documenting the evolution of income and wealth distributions. Piketty and Saez (2003) and later on Saez and Zucman (2016) used income tax data of the US to capture the income and wealth concentration over the previous century. The latter, based on the capitalisation approach, reached conclusions on wealth distribution replying on the observed income flows. This method is considered significant for the top-end households to which a big part of their wealth is held in assets , which further create taxable income flows. Regarding portfolios that do not generate taxable income such as owner-occupied housing, Saez and Zucman (2016) based their analysis on survey data.

As mentioned above, data on wealth internationally have always been very scarce. Davies and Shorrocks (2000) presented in detail the advantages and disadvantages of all the available sources of collecting empirical underpinnings on wealth distribution: (a) household surveys, (b) wealth tax data, (c) estate multiplier estimates and (d) the investment income method.

However, Crawford et al. (2016), when discussing the above methods and their application in the UK, argued that there was lack of any form of wealth taxation meaning that compared to other countries that use administrative data on wealth holdings for tax purposes, in the UK, this data is not significantly available.Footnote 6 Nevertheless, taxes on estates on death are available in various forms and therefore, the ‘estate method’ could estimate the wealth distribution by “multiplying the estate data by the reciprocal of the mortality rate” (pp. 36–37). As for the investment income method, it has also been used for over many years by using the income distribution and a rate of return multiplier. However, none of the last two methods provided any direct measurement of wealth distribution for the UK, nor informed details about the households below the top end. This is because not all properties in the country are liable for inheritance tax or generate income and in particular avoidance of estate/inheritance tax through passing on assets 7 years or more before death (Crawford et al. 2016).

Household surveys in the UK now play a rather significant role in collecting direct measures of the wealth distribution across the country. However, as discussed by Alvaredo et al. (2016), the weaknesses coming from the household surveys on wealth focusing mainly on the low response rate of the participants constitute notable defects in accurately capturing the wealth concentration towards the top tail of the distribution.

Davies and Shorrocks (2000) emphasised that the studies on wealth after 1960s focused more on the causes of the disparities to individual or household wealth. This change in focus was led by the increasing importance of savings for retirement but also as a result of the increasing and improving micro-data sets that offer a plethora of individual and household characteristics that greatly contribute to accounting the differences in wealth.

What about the effect of income inequality on wealth inequality ? Most studies find that increases in income inequality lead to simultaneous increases in wealth inequality . Dynan et al. (2004) when analysing whether households with higher incomes save a higher proportion of their income found that income inequality adds top wealth inequality since the higher income households save more.

Kuhn et al. (2017) used information on income and wealth from HSCF data in order to identify divergent trajectories of income and wealth inequality . Opposed to standard methods, which concluded that a rise in income inequality would lead to increased wealth inequality , the authors found that the opposite was the case during 1970s and 1980s in the US. In fact, during that period, wealth inequality decreased while income concentration at the top income households surged. According to their findings, wealth inequality started rising during the 1990s and it was only at the beginning of the financial crisis in 2007, that wealth concentration started being higher than before the 1970s. As for the period during the financial crisis , they identified that this was “the largest spike of wealth inequality in post-war America” (p. 5). Moreover, over the years that followed 2007–2008, wealth accumulation towards the top of the distribution, increased more than ever within the six previous decades, concluding that wealth distribution in the US nowadays, is more unequal than before (Kuhn et al. 2017).

Similarly, Davies and Shorrocks (2000), when examining the wealth distribution of several countries highlighted that wealth is distributed more unequally than labour income, consumption or total money income across a number of developed countries. As they argued, although Gini coefficient of income range between 0.3 and 0.4,Footnote 7 for wealth, it ranges from 0.5 and 0.9. Similarly, the estimated share of wealth for the top 1% of the households is in the range 15–35% of the total wealth, while their income is less than 10%. Moreover, similarly to Kuhn et al. (2017), they concluded that during the twentieth century, wealth inequality had a downward trend, however, it was characterised by several interruptions and reversals such as the one in the US in the mid-1970s.

According to the literature, consumption is also linked to wealth distribution. Although Muellbauer (2010), Carroll et al. (2011) and others examined the macroeconomic impacts of wealth on consumption, Arrondel et al. (2017), looked at the heterogeneity of the marginal propensity to consume wealth-based household surveys in France . They found that this heterogeneity is generated by disparities in wealth consumption and levels of wealth. One of their main findings is that there is a falling marginal propensity to consume wealth across the distribution for all net wealth components. More specifically, out of the financial wealth, the marginal propensity tends to be higher than the effect of housing assets , apart from the top of the wealth distribution. In fact, the marginal propensity to consume from housing wealth decreased from 1.3% at the bottom of the wealth distribution to 0.7% at the high end of the distribution. On the other hand, the marginal propensity to consume out of housing wealth rises with debt pressure and depends on the composition of debt . They found that the effect of wealth shocks on consumption inequality is limited. Nevertheless, they identified that if stock prices increase, there is a slight increase in consumption inequality, especially at the top of the distribution.Footnote 8

Despite a long history of studies looking at the relationship between wealth and consumption, this question of the impact of housing wealth on consumption is still a subject of an academic debate. Buiter (2008) shows that housing wealth should not be the primary driver for non-housing consumption.Footnote 9 He empirically shows that higher housing wealth increases the cost of housing consumption; therefore, the impact on non-housing consumption should be small. In fact, in his model the only way in which the two could be related to each other is through relaxing the borrowing constraints. This is because housing collateral has a very strong impact on the ability of a household to borrow. Mishkin (2007) finds that increases in housing wealth have a larger effect on consumption than changes in the value of financial assets . Since he recognises that he cannot measure the effect precisely there is also a large body of literature that investigates this effect empirically. The work of Case et al. (2005) and Carroll et al. (2011) not only clearly link increases in housing wealth to consumption but also show that its impact is larger than the wealth effect of stocks. However, Buiter (2008) argues that housing wealth is not macroeconomic wealth as its changes are affecting homeowners and renters differently so that even if changes to house prices have an effect on individual households, the net aggregate effect should be zero.Footnote 10 Although micro studies support the claim that increasing house prices have a higher impact on homeowners there is little evidence that renters’ consumption counteracts this phenomenon (Bostic et al. 2009). There is also research that accounts for the age of the household (Calomiris et al. 2012), and demographic changes that influence the housing wealth effect (Sinai and Souleles 2005); however, the conclusions remain unchanged. There is also evidence that changes in household wealth may not necessarily affect consumption solely through relaxing borrowing constraints as households may also change their saving habits in response to exogenous shocks to the value of their homes. As housing is the major component of most households’ investment portfolios, the impact of an exogenous shock to house values may affect precautionary saving rates and, therefore, affect consumption. Critically, this effect can occur without re-mortgaging thus would not be noticeable as an equity release. Christelis et al. (2015) showed that even when changes in housing wealth are decomposed into an expected and an unexceed component, both still have a significant positive influence on consumption. This shows that housing plays an important role in how households behave and has important implications not only for micro-level decision making but also for aggregate levels of consumption.

Furthermore, Davies and Shorrocks (2000) supported the view that wealth holdings are used for consumption smoothing when consumption is expected to increase or in cases that income is decreasing due to expected or anticipated shocks (e.g., due to unemployment or retirement). “This consumption smoothing role is particularly important when individuals face capital market imperfections or borrowing constraints” (Davies and Shorrocks 2000). Moreover, as described by the authors, the type of the economy and/or society is also defined by the patterns of wealth-holdings individuals and households are following and the way they hold wealth. Hence, several macroeconomic reasons such as the social status which is related to different types of assets can be used to study wealth.

To our knowledge, this is the first time that a study makes use of the latest data on wealth distribution available, that is the Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS) for Great Britain , and tries to relate the findings of this Survey on wealth in time and space, with the evolution of house prices in the country over the last decade. The findings of this analysis suggest that house ownership especially to the most productive regions of the country correlates to higher net worth. Moreover, this ownership seems to have a quite strong relationship with how wealth in these regions is developing over time. Residential prices increase rapidly in government office regions where wealth was already concentrated. This creates further thoughts about accessibility of all groups to these regions or their location decisions. These areas will constitute the most productive locations of the country and offer the highest income which will drive to additional wealth increase, and hence to the empowerment of inequality. Although we cannot infer causality from this trend, however, we notice that it is increasingly concentrated amongst the wealthiest households and it is not only occurring for the overall distribution of households but also, it seems to have very distinctive spatial patterns which are dictated by house prices .

3 Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS) in Great Britain

Focusing on the Great Britain over recent years, there are two sources that provide information and estimates on wealth: (a) the Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS) , which as we will develop in more detail later on, it is “a longitudinal sample survey of private households which started in 2006”, run and issued by the Office for National Statistics (ONS); and (b) the Personal Wealth Statistics (PWS)—which is “a long standing series based on administrative data”—generated by the HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC).Footnote 11

Both of the above sources—WAS and PWS—use the term “wealth”, but they differ substantially in terms of the methods applied for the calculation of wealth and the definitions used in their interpretation of how wealth is distributed across the country. For the purpose of our analysis, we are making use of the WAS . The main reasons against the selection of the PWS is it is not representative of the population. This argument is based on the ground that the statistics of PWS are applied on a sample of forms submitted to HMRC for administrative Inheritance Tax (IT) purposes, required by only estates that obtain a grant of representation (probate) and not a random representative sample of the population. Hence, although the WAS coverage refers to all individuals living in private households across Great Britain , PWS is limited to the sample of estates that need a grant of representation. As per ONS (2016), in 2010, this sample regarded approximately 31% of the individuals in the UK (which is not representative either). Moreover, in order to monitor the effect of house prices on wealth, it is essential the unit in use to be on a household and not on individual level. Since, PWS is presented at an individual level only, there is no direct link between the residence value and the individual wealth estimates, whereas WAS ’ estimates are on a household level. However, some of the disadvantages of WAS for the current study, constitute the following: (a) the fact that series commence in 2006, compared to the long existing series of data of PWS that go back in 1976; and (b) WAS self-reported wealth values are less accurate than tax returns.

WAS is funded by a consortium of government departments: Office of National Statistics (ONS), the Department for Works and Pensions , the HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC), the Scottish Government and the Financial Conduct Authority. “The WAS is a longitudinal survey, which aims to address gaps identified in data about the economic well-being of households by gathering information on level of assets , savings and debt ; saving for retirement; how wealth is distributed among households or individuals; and factors that affect financial planning” (ONS 2015a, p. 2).

For a long time, household wealth data for Great Britain have been very limited with surveys only occasionally addressing only wealth questions.Footnote 12 It was only after July 2006 that WAS started addressing questions on wealth explicitly. Wave 1 consisted of interviews accomplished over 2 years (June 2008), referring to 30,595 households. The same households were interviewed for Wave 2 (July 2008–June 2010), where 20,170 households participated. Wave 3, lasted from July 2010 to June 2012 and lastly Wave 4 covered July 2012–June 2014 with 20,247 private households. The report of the main findings of the latest wave (5), concerning the period July 2014–June 2016, has just been released including interviews addressed to 18,000 households between July 2014 and June 2016.

The samples included in the several waves of WAS covered private households in GB (excluding “people in residential institutions, such as retirement homes, nursing homes, prisons, barracks or university halls of residence, and homeless people”).Footnote 13 WAS contains data at household and individual levels. However, for the purposes of this chapter, we are only making use of the household level.Footnote 14

Due to the fact that a large amount of wealth is held by a relatively small number of households and individuals, WAS oversamples particular households on purpose by using income tax records, in order to address it to households with higher financial wealth. Vermeulen (2015) examined the significance of oversampling in order to generate efficient results for the high end of the distribution. As the author discussed, oversampling is not necessarily dealing with the biases because of the differential non-response and he considered that WAS was possibly underestimating the wealth concentration towards the upper tail. By using both WAS and the Forbes List, while assuming a Pareto distribution, Vermeulen (2015) identified that WAS actually underestimates the top 1% of wealth by 1–5%.

In the reports published by the ONS regarding the WAS , household wealth is divided into four components: property, physical, financial and private pension wealth. These four wealth components are defined as per below according to ONS (2015b, p. 2):

-

Property wealth: considers “the value of any property privately owned in the UK or abroad (gross and net of liabilities on the properties)”.

-

Physical wealth: “includes the value of contents of the main residence and any other property of a household including collectables and valuables (e.g. antiques and artworks), vehicles and personalised number plates”.

-

Financial wealth: accounts for “the value of formal and informal financial assets held by adults and of children’s assets ”.

-

Private Pension wealth: considers “the value of all pensions that are not state basic retirement or state earning related”. Moreover, “the value of private pension schemes in which individuals had retained rights in which they would or have received income”.Footnote 15

As argued by Crawford et al. (2016), physical wealth should be excluded from the sum of the total net wealth as the replacement value of goods is not an appropriate measurement for the value of the items people own. This bias is subject to underestimation/overestimation of the actual value of goods and therefore, should be excluded from the total net wealth.

Crawford et al. (2016) discussed the distribution, composition and changes of the household wealth in GB over the first three waves of the WAS , i.e. between 2006 and 2012. Drawing on the main conclusions of that paper, among other outcomes, the total wealth on average rose (real terms) during this period for the working-age households but decreased for the retirement-age households. Nevertheless, wealth held outside pensions dropped for all apart from the youngest households. Therefore, the conclusion reached was that the increased wealth is driven by increases in pension wealth for that particular period.

3.1 Discussion of the Most Recent WAS Waves 4 and 5 (2012–2014 and 2014–2016)—Wealth Distribution and Inequality Across Great Britain

Looking at the most recent report on the main findings out of the fifth wave of WAS , the aggregate total wealth of all households in GB was £12.8 trillion between July 2014 and June 2016, illustrating an increase in 1.7 trillion from the previous period (2012–2014). Median household total wealth also increased 15% from the previous period being at £259,400 from £225,100 of the last wave. At the same time, wealth inequality is in high levels in GB, as the total wealth held by the top 10% of households is around 5 times greater than the wealth of the bottom half during wave 5.Footnote 16

To continue with the aggregate total private pension wealth of all households in GB over wave 5, it was £5.3 trillion increasing from £4.4 trillion the period before (wave 4). One of the striking findings though in relation to our study is that there was a great increase in the net property wealth for households in London compared with all other regions. More specifically, median net property wealth in London was £351,000 showing a 33% increase from the previous wave (4).

Comparing wave 5 with the previous waves, and more specifically with wave 4 over the period 2012–2014, in wave 4, the net property wealth in GB accounted for 35% of the aggregate total wealth during 2012–2014 (having dropped from 42% during the earliest period for which data are available—July 2006–June 2008). Physical wealth accounted for just 10% of the aggregate total wealth while financial wealth accounted for 14% of it during wave 4. Finally, the biggest share of wealth stands for private pensions i.e. 40% of the aggregate total wealth (having increased from 34% during the first wave in 2006–2008).Footnote 17

Figure 1 presents some interesting findings of the distribution of wealth across households, the composition of wealth among the distribution with significant evidence of wealth inequality in GB. More specifically, Fig. 1a shows the comparison between the top 10% and the bottom 50% of the households across the four waves of the Survey. As can be seen from the graph, there are substantial differences between these two groups of households, but also the shares of wealth components of each group of households have substantially changed over the years. To begin with, during the first wave, we can observe that the wealth components significantly differ between the two groups where the biggest share for the top 10% is the private pensions (42%), followed by the net property wealth (36%), then the net financial wealth (16%) and lastly some physical wealth (6%). On the contrary, for the bottom 50% during wave 1, the biggest share of wealth accounted for net property wealth (41%), followed by physical wealth (34%), which is significantly higher than this of the top 10% group, then private pensions (21%) and lastly some very low financial wealth (4%). A similar pattern can be observed over waves 2 and 3 respectively, while in wave 4 which is the latest period of available data we can observe that: (a) private pension wealth has overall increased during the years for both groups, (b) net property wealth has decreased over the eight-year period for both groups, (c) financial wealth has increased for the 10% of households but has remained the lowest share of wealth for the bottom 50%, (d) physical wealth has remained the lowest share of wealth for the top 10% and has even decreased further during the years, while for the bottom 50% of households, physical wealth remains one of the biggest shares of their wealth and (e) possibly the most significant conclusion for our study is that the wealthiest households have a more diverged portfolio of wealth to which their wealth is dispersed between pension, property and financial wealth across all the waves of the Survey; while for the bottom 50% of households the main source of wealth is in properties (possibly their main residence) and physical wealth (including the value of contents of the main residence or vehicles)—an observation that is notable across all waves.

This Fig. 1a exhibits the components of wealth of the top 10% and bottom 50% of households until 2014. Some interesting findings on the inequality of wealth across households in GB over the latest wave (July 2014–June 2016) that have been included into the latest report released by ONS are related to the household total wealth distribution. As per these findings, the wealth ownership among the different groups of the population both the actual value (in £billion and percentage) some interesting outcomes are the following: (a) although the actual value of wealth of the bottom 50% increased from £962 billion in wave 4 to £1118 billion in wave 5, this group still holds just 9% of the total wealth, (b) the difference can mainly be viewed to the upper and middle wealth classes where, although the total wealth acquired by the top 10% has overall increased since the last wave from £4975 billion to £5595 billion their share has dropped by 1% in favour of the middle class who saw their aggregate wealth increasing from £5176 billion to £6066 billion, (c) another impressive outcome of the latest wave (5) is that the aggregate wealth held by the top 10% is almost 5 times more than that of the bottom 50% of the population (44% or £5595 billion by the top 10% compared to 9% or £1118 billion by the bottom 50%), a finding that highlights wealth inequality across GB.

The above conclusion about the wealth inequality has been very well documented by the literature over the years (e.g., by Atkinson and Harrison 1978; and more recently by Piketty 2014) and we can see that this inequality phenomenon continues being rather evident as wealth is mainly held by the wealthiest households.

Furthermore, by comparing the latest results with the previous waves (3 and 4) of WAS , the aggregate total wealth has increased over the years. More specifically, half of the households in GB hold just over £1 trillion, while the top 10% of households own almost half of the aggregate total wealth; these are figures that constitute evidence of very strong wealth inequality in the country. Some more interesting findings of the latest fifth wave concerning the period July 2014–June 2016, are that: (a) the bottom 10% of households have total wealth of £14,100 or less, (b) the median total household wealth is £260,400 while the top 10% of households have total wealth of £1,208,300 or more and (c) the top 1% of households hold the amount of £3,227,500 or more (ONS 2018).

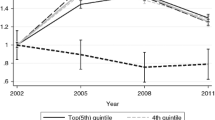

Another interesting component of the ONS report about the wealth inequality in GB, is the calculation of the Gini coefficients of the aggregate total wealth as presented in Fig. 1b. Gini coefficient , which is the statistical measurement of the dispersion of wealth distribution, constitutes the most commonly used measure of wealth inequality and therefore, could not be disregarded.

We have added to this Fig. 1b the most recent outcomes of the fifth wave regarding the most recent period of the Survey. Gini coefficients take values between zero and one, with zero representing a perfectly equal distribution and one presenting a perfectly unequal distribution. As can be observed by the graph, Gini coefficients are consistently high across years and for all wealth components. Some significant outcomes that we could extract from Fig. 2, are: (a) physical wealth is the least unequal wealth component taking values between 0.44 and 0.46 across all waves—a figure that was expected as it constitutes the main wealth component of the bottom 50% of households. (b) The most unequally distributed wealth component is financial wealth with very high Gini coefficients from 0.81 over the first two waves to 0.91–0.92 over the three waves showing that financial wealth inequality has dramatically increased over the last 6–7 years. This finding is another evidence of high wealth inequality as financial wealth is the main component of the wealthiest households. As observed also by the Office of National Statistics, this increase in Gini coefficients of financial wealth over the last few years can be interpreted as difference in recovery of financial assets after the economic recession by those with higher levels of financial assets (i.e. the biggest losers were the lower wealth groups). (c) Private pension wealth is the only wealth component with decreasing Gini coefficients over the years. (d) Last, but not least, property wealth component has steadily increased over the years from 0.62 over wave 1 to 0.67 during the last wave. This shows a continuation in worsening of inequality in net property wealth between 2006 and 2016 (ONS 2018). This latest point constitutes a very strong evidence of the fact that the increase in house prices over the last years have misbalanced the net property wealth of the different groups of the wealth distribution in favour of the wealthiest households.

(Source Own calculations using data from Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS) —Office of National Statistics [For the number of households by region (2015), data from ONS were used available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/families/adhocs/005374totalnumberofhouseholdsbyregionandcountryoftheuk1996to2015])

Percentage of aggregate wealth by region, a wave 5, July 2014–June 2016, b wave 4, July 2012–June 2014 and c Wealth per household by region (2015)

The next part of the discussion is looking at the distribution of wealth across the government office regions of GB (Fig. 2).

From this graph, it is obvious that wealth is unequally distributed not only across households but also across the regions of GB. More than 50% of the aggregate total wealth is concentrated towards the South of England (South West, South East and London) and especially the capital and the South East region. The rest of the country has a relatively more dispersed wealth distribution. It is interesting to note the difference in households’ wealth by region. As can be seen from Table 2c, the average wealth held by households in Greater London region and South East is way above the country’s average, in South West and East England moderately above average while to all the rest of the regions, the average household wealth is below average. In fact, in certain regions, it is even two or three times less than the household wealth of South East and London.

It is also very interesting to look at the findings of WAS regarding the Property wealth component in particular. As already mentioned, aggregate net property wealth in wave 5 accounted for 41% of the growth total wealth between waves 4 and 5, increasing by 17% i.e. from £3.9 trillion to £4.6 trillion over the period 2012–2016.Footnote 18

To continue on the above findings on net property wealth, it is interesting to discuss the property ownership rates according to the location of the main residence of the household. ONS illustrates graphically the percentage change in the distribution of household net property wealth by region of residence where net property wealth includes the ownership of the main residence and any other property.Footnote 19 From this figure by ONS, the percentage change in median along with the 1st and 3rd quartiles of the distribution are presented where, during the period July 2012–June 2016, net property wealth across GB was unequally distributed and this inequality evolved further during these years. The post-crisis results show that apart from the North East region, all the rest of the regions of GB have a positive growth of net property wealth. The results highlight the striking increase in the net property wealth of London region. Since all quartiles of net property wealth of London region sharply increased within this short period of time, this gives a strong indicator of the house price increase particularly in London.

The question that has been generated out of the above figures is: How have house prices affected the evolution of this wealth inequality across the country? It is a fact from the above figures that wealth is unequally distributed across households and also unequally concentrated across the regions of GB. However, how the change in house prices over these years in the several regions of the UK have contributed further to wealth inequality has not been examined, or whether house prices have actually contributed in decreasing the disparity of wealth. The arguments behind the support of the first case, i.e. house prices have contributed to the increase in wealth inequality , would be based on the logical aspect that wealthy households would invest in the property sector and therefore, the increase in house prices would increase their wealth further. The supporting arguments of the opposite case, i.e. house prices have contributed to minimising the inequality of wealth, lay with a different but logical argument too, that a great share of wealth held by the bottom and middle-class households is mainly consisted of property wealth (Fig. 1a); especially the value of their main residence and therefore, any change in house prices would drastically and positively increase their levels of wealth, hence, wealth inequality would decrease between the top and the middle/bottom part of the distribution. Kuhn et al. (2017), when investigating the US market, identified that “while incomes stagnated, the middle class enjoyed substantial gains in housing wealth from highly concentrated and leveraged portfolios, mitigating wealth concentration at the top” (p. 3).

However, one could say that there is a third case, i.e. both cases are true and the heterogeneity observed both in wealth distribution and in house prices across the different regions of the country create a third different combination of these two scenarios.

Davies and Shorrocks (2000) mentioned that when owner-occupied housing is the major component of the non-financial assets , then wealth is more equally distributed. Nevertheless, as these authors explicitly discussed, the opposite might be the case in countries where land values are especially important.

3.2 House Prices and Their Role on Wealth Distribution

Wolff (2017) in analysing the household wealth trends in the US between 1962 and 2016 highlighted the significance of the housing value cycle on wealth trends. As discussed by the author, one of the most notable effects on net worth leading to the Great Recession of 2007 was the house price explosion prior to it and the immediate collapse of the housing market. At the same time, the home ownership rate in the US significantly expanded over the last three decades and continued to increase but with a slower pace between 2001 and 2007. However, during the crisis of 2007–2009, the home ownership rate slightly decreased while after the crisis, although house prices recovered, home ownership rate continued to drop.

In the same paper, it was explained that the housing bubble in the years prior to the crisis, was largely due to the expansion of the credit availability for housing transactions and re-financing. This fact was because of: (a) the re-financing of the primary mortgages; (b) second mortgage and home equity loans or increased outstanding balances; and (c) softer credit requirements with either none or limited documentation—in turn, were so-called ‘subprime’ mortgages with excessively high interest rates and “balloon payments” at the expiration of the loans. For the above, the average mortgage debt per household hugely increased in real terms (more than 59%) between 2001 and 2007 while the outstanding mortgage loans as a share of the house values also increased (Wolff 2017).

House Prices in GB, followed a similar pattern to the US, in most of the regions during the last two decades. This pattern, however, affected in different magnitude each region of the country. House prices across the country sharply increased during the decade before the financial crisis , while towards the end of 2007 started collapsing until mid-2009 when house prices started recovering again in most of the regions. However, house prices in GB appear rather heterogeneous across the different regions of the country and is characterised by huge discrepancies among the different areas of the North, the middle and the South. House prices in the Greater London area and the South East have been rising faster than the other regions of the country.

Similar to the heterogeneity patterns across regions, house prices have also evolved differently over time and space/regions. Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of house prices in GB during and after the financial crisis . More specifically, it presents the percentage change of the median house price over the years 2007–2016. As can be seen, within this decade, since 2007 and especially after the end of the recession, house prices have sharply increased in most of the government office regions of GB. The median house price in London region has risen faster reaching a striking 68% increase over the last decade. East England and South East regions follow with 36 and 34% increase in the median house price of each region respectively. The South West and the Midlands (East and West) regions also present high growth rates (21, 17 and 16% respectively), while the north regions of England (East and West), Yorkshire and Humber, Scotland and Wales have reaching more modest house price growth rates (6–11%). As can be observed from Fig. 3, the market not only has completely recovered from the financial crisis , but instead house prices have outperformed in many regions of the country.

In particular, the South East has seen a much faster growth of house prices with double-digit annual rises persisting in London. While in most areas house prices declined during the financial crisis of 2008/2009, in some regions they have rebounded quicker than in others. In fact, in some places growth remained positive even during the economic downturn. The most expensive boroughs of London and the most unaffordable housing markets (as judged by ratio of house prices to earnings) outside of the capital (such as Cambridge and Oxford) continue to attract not only high house prices but also high income and wealth, including households that are able to invest in the property sector. This results in a high standard deviation of house prices as well as of their growth rates across GB.

As observed by Kuhn et al. (2017), the effect of house prices on households’ wealth is substantially different along the distribution of wealth . This would mean that any changes in house prices would have a significant but differential effect on the several household groups as well as on the evolution of wealth inequality . In order to quantitatively identify this effect, the authors created a measure of house price exposure on wealth growth :

where

- \(\frac{{\Delta W_{t + 1} }}{{W_{t} }}\) :

-

stands for wealth growth ,

- \(\frac{{H_{t} }}{{W_{t} }}\frac{{\Delta p_{t + 1} }}{{p_{t} }}\) :

-

stands for the house price component, and

- \(g_{t}^{R}\) :

-

stands for the residual component which accounts for wealth growth caused by all other reasons but house prices

Therefore, any changes caused in house prices are reflected on \(\frac{{\Delta p_{t + 1} }}{{p_{t} }}\) which are adjusted by the house prices exposure \(\frac{{H_{t} }}{{W_{t} }}\). This would mean that with house price increase, a bigger exposure on house prices , would cause further wealth growth . Any differences in saving rates of households or other sources of wealth would be included in the residual component (Kuhn et al. 2017).

3.3 Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework presented so far from the literature, the presentation of the main findings of the WAS and the arguments on wealth distribution and wealth inequality in relation to house prices in time and space draw a picture of increasing wealth inequality , with strong concentrations towards the right tail of the distribution. Property wealth seems to be a significant wealth component for all household groups (top, middle class and some lower wealth households) and strongly involved in the evolution of their total wealth. House prices (especially considering the main residences of the middle and least wealth households) constitute the most significant asset components of property wealth and therefore, there are strong evidences that their evolution over time and space, i.e. over the last decade in focus and across the different government office regions of GB, dictate the patterns with which wealth is distributed over this period and across the regions.

But how does the house price evolution over the last decade correlate with the household wealth distribution of the different government office regions of the country? This is an interesting question that we try to approach. Although it is difficult to fully uncover the relation and patterns, but also to infer the actual causality of this relationship, to the following section, we have developed an empirical approach for GB.

4 Empirical Investigation

The method that we apply in this chapter for the identification of the effect of house prices on Wealth is the Inter-Quantile regression with bootstrapped standard errors.

The main aim of quantile regression is to estimate the conditional median or any other quantiles of the variable of interest. It constitutes the extension of a linear regression, as it is mainly used when linearity is not applicable. The reason why this method has been selected in particular is because it is the most suitable method when conditional quantile functions are of interest.

Moreover, a significant advantage of the quantile regression which is the main difference from the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) is that its estimates are much more robust with the presence of outliers to the variables of interest. In addition to that, several measures of central tendency and dispersion offer a much more comprehensive analysis of the variables when using the quantile regression.

In particular, an Inter-Quantile Regression allows much easier interpretation of differences between different groups of the outcome variable distribution. In our case this is total wealth. As we have stipulated earlier, we assume that households with different levels of wealth will be exposed differently to changes in the dependent variables.

Therefore, the motivation for applying this empirical method is that we assume that the impact of different determinants of net wealth is conditional on total wealth. In this way, QR provides the capability to describe the relationship between a set of regressors and the variable of interest at different points in the conditional distribution of the dependent variable. Hence, by applying the Quantile Regression, we achieve our estimates being more robust against the outliers in our response measurements. This robustness to non-normal errors and outliers of QR provides a deeper understanding of the data, enabling us to account for the impact of a covariate on the distribution of y, and not solely its mean. In our study, taking into consideration that both wealth and house prices are measurements with great discrepancies among their observations including many outliers, the distribution of the values around their mean would create robustness issues.

The inter-quantile regression applied in this study is the regression of the difference in quantiles.

The model used is:

where

- W i, t :

-

stands for the net aggregate wealth,

- E i, t :

-

stands for the net financial wealth,

- H i, t :

-

stands value of the main residence and reflects the impact of changing property values on wealth.

- \(g_{t}^{R}\) :

-

stands for the residual component of Eq. 1 and in this regression takes the form an error term.

In this specification we capture the increase in the net financial wealth directly as although important to avoid the omitted variable bias in our estimates, we do not assume that it is of critical importance to our research question. Instead, we focus on property wealth, which we approximate with the value of the residence.Footnote 20 Together the two componentsFootnote 21 represent total wealth for the vast majority of the population and provide estimates that support the view that wealth growth depends on the price of the residence. For simplicity other components of wealth (pension and physical) are omitted. These are, of course, missing variables in this model but testing models that included them did not affect the results while it significantly increased computation time and the accuracy of the bootstrapped error estimates.

Since we have shown that house prices have been developing at different rates across the country we expect that the value of the main residence may be more important for different quintiles of the distribution. From this, we can point out that as house prices are increasing the households that own their homes are likely to slowly graduate to higher quintiles of the population while the households that do not benefit from the capital value appreciation of properties mainly rely on income and financial wealth. Note that this variable does not reflect the value of a property owned by the household but of their main residence only. This is a quite important distinction as it allows us to focus on the households that live in the locations where house prices are the highest and directly relate their household wealth with the value of their residence. It also enables us to link the location of the household wealth (to the respective government office region) with the location of the main residence of the household and not with their property wealth in general.

In contrast, the financial wealth is the component of household wealth that is not affected by the growth of house prices as there is no direct link between them. Its spatial distribution is more likely to stay constant over time and we expect it to be highly important for the richer households.

\(g_{t}^{R}\) stands for the residual component which accounts for wealth growth caused by everything else than house prices and financial wealth. Total wealth is measured as the sum of all wealth components listed in Sect. 2. We regress this value on the value of the main residence to test the hypothesis represented in Eq. 1. Including financial wealth into the regression controls for the omitted component of wealth that is likely to be correlated with the value of main residence. All other determinants of wealth are reflected in the residual term.

4.1 Data and Variables

As extensively discussed above, the data on Wealth distribution for GB are obtained from the WAS performed in four waves. The first wave consisted of interviews addressed to 30,595 households. Out of these households, 20,170 of them were interviewed again during the second wave. Finally, for the third and the fourth waves participated 20,247 private households (UK Data Service 2017). These datasets include information on the aggregate wealth of households along with some distinction to the several wealth components such as net financial wealth, value of the main residence and many others.

Regarding data that concerned the house prices of the different governmental office regions of the country, these have been collected from the Land Registry. This dataset includes all market transactions that occurred between 2007 and 2016. As shown in Fig. 3 and already extensively discussed, the average change in transaction prices was around 20%. However, this varied greatly across GB.

4.2 Empirical Results

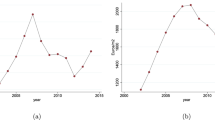

The intuition behind using a quantile regression is supported by Fig. 4, which shows that for wave 4 different parts of the wealth distribution have vastly different mean estimates. Due to data unavailability for wave 5 (concerning the period between July 2014 and June 2016) at the time of this analysis, wave 4 was the latest wave released (i.e. over the period July 2012–June 2014). It is clear from this figure that wealthier households benefit more from additional units of financial and property wealth but the most striking feature of the regression is the discontinuity between the 75th quintile and the full sample. This sharp increase right after the 75th quintile suggests that the wealthiest 25% households in GB react to changes in their wealth differently than the rest of the respondents.

Table 1 shows the results of a regression of total wealth on the value of main residence and net financial wealth from different percentiles in different time periods. The waves that have been used to this regression are the first four waves released by the ONS (i.e. referring to the time period July 2006 to June 2014) as at the time of the analysis these were the only waves available. The results are based on an inter-quintile regression, which allows us conditional means for different parts of the distribution. The estimates are presented for four categories of household wealth distribution selected so that the number of households in each group is equal.

As can be seen from Table 1, one of the most striking changes when progressing from waves 1 (2006–2008) and 2 (2008–2010) to waves 3 (2010–2012) and finally to 4 (2012–2014), is that financial wealth becomes insignificant for poorest households (columns 3 and 4). While the impact of financial wealth on the bottom 25% households’ wealth in the first two waves (2006–2010) is much smaller than for the wealthier respondents, all households increase their total wealth by holding financial assets . As can be seen, in waves 1 and 2 (2006–2010), net financial wealth appears significant across all quintiles of the distribution. However, in the latest waves—waves 3 and 4 (2010–2014)—this is not the case, as the results suggest that the poorest households (bottom 50% of the households) hold virtually no financial assets . Instead, their wealth is substantially and increasingly determined by the value of their main residence. This is illustrated by the fact that the coefficient of the value of the main residence for the bottom 50% of households increases steadily with time. This points to the conclusion that between the years 2006 and 2014, while financial assets became virtually irrelevant for the wealth of the poorest households, values of their main residence became the main source of their wealth.

However, the declining importance of financial wealth is not unique to households in the bottom half of the distribution. In fact, it appears that this occurs uniformly throughout the sample. In wave 4 (2012–2014), all households are less sensitive to financial assets and the wealth of the richest is interestingly two times less dependent on this type of wealth than it was in wave 1 (2006–2008). This difference shows how important changes in property wealth are for households in GB. With time, the impact of financial wealth decreases substantially which shows that the importance of the other component of total wealth must become more significant.

4.3 Discussion of the Empirical Results

In the following table, Table 2, we present the percentage changes of wealth to the different household quartiles across the government office regions of GB for the two latest released waves of WAS (i.e. 2012–2016). Although raw data for wave 5 have not been released by the time of this analysis and discussion, the recently released report on this fifth wave includes some very useful information.Footnote 22

As can be seen from this table, between 2012 and 2016, the median of households’ wealth increased by 60% in London, which is more than twice as much as for any other part of the country. Within the same period, Yorkshire and Humber median property wealth increased by one quarter, similarly to North East by 23%, while the North West, West Midlands, East England, the South East and Scotland had a moderate increase between 7 and 13%. Median household wealth in East Midlands and South West had a very slight increase of 1%, while the only government office region where the median household property wealth decreased was Wales by 5%. The figure is even more striking in the decade between 2006 and 2016, when median wealth increased dramatically in London, somewhat in the South East (15%), moderate to null increase in South West and Scotland, whereas median household wealth decreased in most other regions. The most outstanding decrease was in North East (39%) followed by East Midlands (21%), Wales (18%), West Midlands (16%) and moderate decrease to the rest of the regions.

The concentration pattern is evident for households that own their property as appreciation of house prices in London and the South East clearly allowed it to accumulate more wealth in these regions than the rest of the areas of the country. Interestingly, the most important difference between property owners and an average household is that the former group increased its median wealth in all regions apart from the North East. This suggests that wealth is increasingly owned by those who can afford to buy real properties while those who cannot see their wealth decreasing sharply.

The above results paint a dramatic picture of wealth concentration amongst the richest households that reside in the wealthiest regions of the country. As can be seen, there is also striking evidence of the fact that property ownership allows higher wealth accumulation. In fact, it appears that, on average, households that did not own any property or live in London or the South East were worse off while property owners in the capital saw their wealth increase dramatically.

More specifically, as can be seen from Table 2, looking at the median property wealth of the last two waves only, 2012–2016, property owners in London area have seen their wealth increasing by 33% within these four years. A substantial but more moderate increase can be observed in most other regions (5–12%) while the only region where property owners have seen their household wealth decreasing are in North East. Moreover, as for the decade between 2006 and 2016, these results confirm a more striking picture, considering also the effect of the financial crisis to the volatility of the median household wealth. As it can be observed, the median household wealth of the property owners in London region outperformed over this decade, where Londoners property owners have seen their wealth increasing by 60%. Other substantial increases in median property wealth can be observed in South East (25%) and Scotland (19%). Moderate increases in median household wealth can be seen in East of England and South West (11%), East Midlands and Wales (6 and 4% respectively). Slight to no change can be observed in North West, Yorkshire and Humber and West Midlands, while the only region where there is a negative growth to the median household wealth to the property owners of North East region.

Our results are also consistent with the expectation that the wealthiest households have much more varied sources of wealth than the poorest ones. Differences in income and asset allocation decisions may drive this disparity but it is difficult to establish the causal link from the available data on wealth from the WAS . Although in our analysis we attempt to show that geographical location plays a critical role in determining wealth and its growth over time, we acknowledge that there are several other factors that are not accounted for by the existing research. A concern for our results would be if the unidentified factors were correlated with house prices . For example, it may be that house prices in London increased because wealthier households have moved to the city. In our analysis this would present itself as an increase in wealth in the capital. In this sense, the results need to be interpreted as a high concentration of wealth in places where house prices are the highest. This however, does not mean that homeowners do not benefit from this trend. In fact, it appears that as the concentration of wealthy households in the South East regions grows the local homeowners are positively affected while renters see their living costs increase. This suggest an intersection between income and wealth inequality as those with either higher wealth or income appear to be crowding out those who do not own a property in the most desirable locations and cannot afford to either buy or rent it. The above can already be noticed to a number of cases in several posh or appealing neighbourhoods of the regions of the country, but especially London. This means that as the geographical concentration of wealth is growing, its benefits are accessible to an increasingly narrow group of households who either are already wealthy (through owning properties in the most desirable locations or otherwise) or have an income high enough to rent or support a mortgage in the most expensive locations. Higher house prices are correlated with higher wages but as the ratio of house prices to income in London and the South East has increased significantly more than in other parts of the country it is clear that accessibility of those locations to the poorest households has decreased. This has multiple implications, mainly for the distribution of wealth and income at the low end of the scale. While the lowest earners who own properties in London benefit from rising house prices and growing wages, those who are not homeowners see their net income decline. This means that the locations where wealth concentrates become increasingly exclusive, which has consequences for location decisions and contributes to the growing economic disparity between geographical locations. It appears that house prices play a crucial role in shaping wealth distribution but this house price growth happens not only through the increasing capital values but also through giving access to the highest income.

The unequal distribution of growth is quite likely to be endogenous to housing prices in the UK. The work of Hibler and Robert-Nicoud (2013) and Cheshire (1999) shows that housing supply is strongly related to land use regulations. As residents can influence local planning policy, they have an indirect effect on housing supply. In areas where houses are expensive the local population has a higher incentive to ensure that no new land is made available for construction. This is evidenced in the not-in-my-backyard attitude, which is especially prevalent in wealthy locations (Dear 1992). This suggests that political power shapes the supply of land for housing and determines the elasticity of prices to changes in demand. Consequently, the same change in demand would affect house prices more in wealthier locations where demand is less elastic. This means that the problem of increasing spatial disparities in income across the UK (documented by Martin et al. 2016) translate into actually magnifying the problem of wealth inequality . Although income growth is unequally distributed across UK locations, as presented above, a unit change in income will affect housing demand equally everywhere. However, with housing supply being more constrained in areas where more wealth is concentrated, the impact of a unit increase in demand would have a higher effect on house prices in places where homes have been already expensive. This is clearly consistent with Fig. 3, which shows that the house prices grew the quickest in locations where they were the most expensive to begin with. The correlation between income increases in places where house prices grow the most may not necessarily be unidirectional. While increasing incomes raise demand for housing there is also strong evidence that increasing house prices can affect local companies. A recent development in financial research shows that in locations where house prices increase entrepreneurship rates are also higher and the new firms are more successful (Corradin and Popov 2015). This shows that alleviating credit constraints allows higher economic growth and may lead to an increase in local income. In turn this may have an impact on housing demand.

This problem of income and wealth peaking or bottoming out in the same geographical areas is at the core of modern economic challenges in which income and wealth concentrate not only on people but also on space, identifying particular places and regions that are already at the top end of the distribution. The result is an increasing polarisation of economic resources in which the main winners are less correlated to productivity of individuals and more to their initial endowments. The key point is that changes in house prices are exogenous to renters (whose wealth does not benefit from increases in house prices ) and households at the bottom end of the wealth distribution (who have little influence on where they live) while they may be at least partially endogenous to owners of the most expensive properties who have the highest income and are the only group that has a choice of where to live and whether to own a house or not.

All of the above results are consistent with our theoretical analysis and the hypothesis that house prices are a critical determinant of wealth not only because they are its significant component for homeowners but also because they affect other determinants of wealth. Importantly this applies not only to the level of this variable but also to its growth . Clearly, households that start from a higher base appear to accumulate wealth faster. However, the key contribution of our analysis is that we also show the correlation between the initial value of the residence and the growth rate in wealth. The causal process we suspect is driving this finding is not simply that higher wealth allows quicker accumulation of it, but also that location matters for wealth growth . Living in a location where house prices are high to start with gives the household an advantage in terms of access to finance and employment. These translate into better opportunities to grow and accumulate wealth over time. This is an additional component of wealth that has not been considered to date and is completely separate from the fact that house value appreciation increases household wealth.

5 Summary and Conclusions

The aim of this chapter is to identify the connection between the evolution of wealth and house prices as a significant share of household wealth in GB. Due to data availability on wealth in GB only between July 2006 and June 2014, our analysis was restricted in empirically looking within this short period of time only.

The theoretical framework of this study is built on the fundamental principles of wealth distribution and theoretical along with empirical evidence on wealth inequality around the world over time. The heterogeneity observed to household portfolios and their differentiated composition lead to a systematic variation of both wealth and income distributions that consequently drive to changes in wealth and income inequality across people.

Our focus is predominantly concentrated on the evolution of wealth distribution in GB over the last years and the links between this progression with the evolution of house prices . By using the main findings of the WAS , conducted in GB in waves over the last years, we examine the household distribution of wealth and its components across the government regions of the country. Moreover, we consider the evolution of house prices by looking at the percentage change in the median house prices of each region over this decade showing evidence of wealth concentration not only across the different income and wealth groups of the population but also across space.