Abstract

This chapter gives an overview of the development of current diagnostic criteria for REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD) and specifies qualitative and quantitative diagnostic polysomnographic (PSG) criteria. Minor differences and controversies between the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD), Third Edition (ICSD-3), and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria will be discussed, as well as open issues. Apart from presenting the current diagnostic criteria for RBD, this chapter is an introduction to the subsequent series of chapters related to the diagnosis of RBD and other PSG findings, namely, Chap. 19 (Wing YK group), Chap. 20 (Cesari M and Jennum P), Chap. 21 (De Cock VC), Chap. 26 (Manni R and Terzaghi M) and Chap. 31 (Puligheddu M, Fiorini M and Ferri R). Finally, the chapter will also discuss current limitations in the diagnosis of RBD and their potential consequences and additionally refer to new screening methods for RBD and their potential future applications.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD), Third Edition (ICSD-3) [1], diagnostic criteria for REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) rely on vocal and behavioral manifestations and additionally require a background of increased tonic and/or phasic electromyographic (EMG) activity in the polysomnography (PSG), thus seeming unequivocal at first sight. However, when looking into the details or in particular situations, the diagnosis of RBD is not always straightforward [2, 3], and even in the official diagnostic criteria, ambiguities remain, which will be discussed below.

2 Historical Development of the Criteria for RBD

In a historical context, RBD was first recognized as a diagnosis in the 1990 “International classification of sleep disorders: Diagnostic and coding manual” criteria [4], after the first systematic description in 1986 [5]. The first diagnostic criteria for RBD [4], initially listed as number six among the “parasomnias usually associated with REM sleep”, required as minimal criteria limb or body movement associated with sleep mentation plus at least one of the following: harmful or potentially harmful sleep behaviors; dreams appear to be acted out; and sleep behaviors disrupt sleep continuity. In the ICSD-I revised (2001) [6], there was no change in these minimal RBD diagnostic criteria.

In the 2005 ICSD-2 [7], the RBD criteria were slightly modified. At least one of the following was required: (1) sleep-related injurious, potentially injurious or disruptive behaviors by history and (2) abnormal REM sleep behaviors documented during PSG monitoring, as well as the absence of electroencephalographic (EEG) epileptiform activity and the exclusion of other disorders as possible explanation for the sleep disturbance. Therefore, the presence of RBD behaviors either by history or documented during video PSG (vPSG) was required, allowing a diagnosis of RBD even in the absence of a suggestive clinical history in case of clear RBD behaviors during the vPSG.

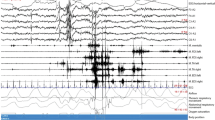

Over time the criteria changed from a focus mainly on the clinical history, which is important but has clear limitations, to a focus on vPSG, with documentation of movements/vocalizations and REM sleep without atonia (RWA) . Moreover, over time it has been recognized that the well-known large or violent complex behavioral outbursts in RBD account for only a very small proportion of all REM-related movements [8]. Therefore, the requirements that behaviors are harmful/potentially harmful and the apparent “acting out” of dreams (which can be subject to interpretation variance in case of small movements) are not included anymore in the ICSD-3 [1]. Moving further in this direction, prodromal phases of RBD have been identified (see below, and Fig. 18.1) [8,9,10], which are not recognized by the current diagnostic criteria.

Progression of neurophysiological and behavioral findings in RBD [8]. Neurophysiological and behavioral findings on polysomnography (PSG) and electromyography (EMG) progress along a continuum from normal to prodromal rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD), isolated RBD (iRBD) and RBD with overt α-synucleinopathy. FDS flexor digitorum superficialis, RBE REM sleep behavioral events

3 Diagnostic Criteria: Currently Valid and Accepted Standards to Diagnose RBD

The currently validated and accepted standards to diagnose RBD are shown in Tables 18.1, 18.2 and 18.3: the ICSD-3 [1] criteria (Table 18.1), the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events, Version 2.4 [11] (Table 18.2) and criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition [12] (DSM-5, Table 18.3).

3.1 RBD Diagnostic Criteria in ICSD-3

The diagnostic criteria of the ICSD-3 [1] are reported in Table 18.1. A footnote on the criterion C, “polysomnography demonstrates RWA”, links this criterion with the respective most recent version of the AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events [11] (Table 18.2).

The diagnostic criteria also mention that a provisional diagnosis of RBD can be made in patients with a typical history and typical video documentation in video PSG but who lack sufficient RWA in occasional circumstances, elaborated further below, or when vPSG is not readily available. The fact that individuals with RBD are typically alert, coherent and oriented upon awakening (as is typical of REM sleep awakenings) is listed among the notes belonging to the diagnostic criteria but is not required as a criterion by itself, because this would naturally make a diagnostic awakening obligatory. It should also be noted that medication-induced RBD can be diagnosed as RBD according to current criteria.

3.2 RBD Diagnostic Criteria in DSM-5

The DSM-5 [12] criteria are presented in Table 18.3. It becomes evident that in the DSM-5 diagnostic manual used in psychiatry, there is a major difference with the classic ICSD-3 criteria, as it is stated that a diagnosis of RBD can be made based on a suggestive history without PSG documentation in patients in whom an α-synuclein disease has been diagnosed. On the one hand, it is in fact true that an established diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD), multiple system atrophy or dementia with Lewy bodies makes a diagnosis of RBD significantly more probable, if the typical behavioral or PSG signs of RBD are present, based on the simple fact that RBD is so prevalent in these diseases. On the other hand, it needs to be emphasized that even with these disorders confounding conditions can exist as RBD mimics, namely, with sleep apnoea [13] and periodic leg movements [14] that remain undetected if PSG is not performed. Of note, the DSM-5 criteria speak about “repeated episodes of arousal” [12] where RBD jerks and behaviors can occur without arousal and arousal could be seen as a consequence of impact or injury during “dream enactment ” behaviors.

4 Strengths and Drawbacks of the Current Criteria

Some investigators have raised the question of whether there should be a minimal duration of REM sleep in a PSG recording to allow for or rule out a diagnosis of RBD, and this is mentioned as an open question in the ICSD-3 [1]. In the opinion of the authors, if such a minimal duration criterion is introduced, it might probably be short. As in most cases with typical RBD, the relative amount of RWA in the EMG [15,16,17,18] and the number of behavioral episodes in the video [19,20,21] are high, so that few minutes would be expected to suffice. Nevertheless, other experts recommend a minimum REM sleep duration of 10% of total sleep time to be on the safe side to diagnose RBD, and in case of shorter REM duration, a second vPSG should be performed. Some authors have even suggested that in very selected difficult cases with advanced neurodegeneration, where EEG during PSG recording is often seriously altered and PSG also poses a high technical challenge, a typical appearance of RWA and behavioral jerking or episodes are so diagnostic for RBD that REM sleep per se can be recognized on this basis and RBD can be confidently diagnosed [22].

Another problem in the diagnosis of RBD according to ICSD-3 may be the lack of sufficient RWA in patients with otherwise clear RBD. One way to overcome this is using, in addition to EMG of the muscle mentalis, EMG recording of the upper extremities, as suggested by the Sleep Innsbruck Barcelona (SINBAR) group [15, 23]. The sensitivity of the extended montage including the upper extremities is considerably higher (91.8%), as compared to muscle mentalis alone (81.6%) [3]. The SINBAR montage is mentioned in the ICSD-3, but recording of the upper extremities is not yet obligatory for diagnosis of RBD up to now.

5 Polysomnography in the Diagnosis of RBD

Among all the parasomnias, RBD is the only one that mandatorily requires PSG for a definite diagnosis.

Since the first description of RBD in humans by Schenck and Mahowald [5], multiple studies have reported specific PSG characteristics. Chapter 20 is devoted to video-PSG findings in RBD, which can be subdivided into PSG (EEG, EMG, electrooculography, etc.) as well as videographic findings, and can be subject to visual and automatic analysis. Novel machine learning-based techniques are in development and presented in this chapter.

5.1 EMG in the Diagnosis of RBD

The different EMG methods which are currently used for the scoring of EMG activity in the diagnosis of RBD are explained in Chap. 31, which provides an overview and review of manual and computerized scoring methods. Manual scoring methods based on visual analysis have been demonstrated to provide a reliable basis for quantification of abnormal EMG activity, and different methods have been validated [24]. However, manual scoring of RWA is very time-consuming and can only be performed by highly skilled raters. For this reason, automatic scoring softwares have been developed [18, 25,26,27]. One of these systems can automatically score the upper extremities, in addition to the mentalis and submentalis muscles [27]. An overview of the computer-based automatic scoring of RWA is given in Chap. 31.

At present, however, this specific automatic analysis is available as integrated software only within the PSG system of one manufacturer [27]. Given the importance of an early and reliable diagnosis of RBD, and the complications of time-consuming manual EMG quantification, it can be expected that not only the analysis of the REM atonia index and the SINBAR automatic analysis programs will be used [28] and further developed, but also other programs, based on EMG or other neurophysiological signals, will be probably developed in the future.

5.2 Video and Other Recordings of Movement and Sound

In Chap. 21, Valerie Cochen De Cock provides a detailed overview of the current status of video studies in RBD and what their findings may implicate for the pathophysiology of RBD. Apart from the phenomenological aspect outlined in Chap. 21, movements and vocalizations may soon gain importance as diagnostic instruments for RBD [8].

The characteristic feature of RBD is not only the appearance of elaborate, complex, often violent and apparently dream-enacting behaviors, which have drawn clinicians’ and investigators’ attention since the beginning [29], but also the much more frequent elementary and minor extremity and body jerks, which are continuously present during REM sleep [19, 20, 30, 31] as a manifestation of “background jerking” [8].

In addition to quantification of increased EMG activity, these jerks are another hallmark of RBD, and their potential as an objective treatment outcome measure remains to be investigated [8].

High-quality video monitoring could be one method to detect these jerks, and the suitability of other methods (e.g. actigraphy) remains to be established [32].

Vocalizations may prove to provide the basis for additional diagnostic tools for RBD [33,34,35]. In difference to regular sleep talking, the hallmark of RBD-related vocalizations is the large variability of vocalizations, including intense emotionality, as found with loud swearing and angry phrases.

6 Reconciling the Terminology in RBD

This paragraph deals with a new designation of “isolated RBD” [8], which has been suggested to replace the former terms idiopathic RBD or cryptogenic RBD [8, 36], and with the new concept of “prodromal RBD” for which clear diagnostic criteria have been defined and which now can be distinguished from isolated RWA .

Historically, the presence of RBD alone in the absence of any comorbid neurodegenerative or other disease was called idiopathic RBD , but increasing research has made clear that a very large proportion of these patients will develop α-synuclein disease in the subsequent years and that in the stage of “idiopathic” RBD slight abnormalities of waking EEG, cognitive function, motor function, olfactory and visual function and others can be found [8, 37, 38] (see also Chap. 36 by Ron Postuma). Therefore, more than 10 years ago Ferini-Strambi et al. suggested to replace the term idiopathic RBD with cryptogenic RBD [36].

In the past decade, considerable research advances have been made, and it has become clear that even in patients with very long-standing (more than 10 years) persistent “idiopathic” RBD, when they are examined in detail, other biomarkers of α-synuclein disease can be found, which means that in these patients, despite still having idiopathic RBD, manifest neurodegeneration is nevertheless present [39].

On the basis of this evidence, it has been suggested by Högl, Stefani and Videnovic in early 2018 [8] that the designation of RBD should be changed from idiopathic RBD or cryptogenic RBD to “isolated RBD” (iRBD) [8], reflecting the current stage of research more accurately, while not causing any change in abbreviation, viz. iRBD remains iRBD . This change in designation is fully justified because underlying α-synuclein pathology has been clearly demonstrated in multiple in vivo and postmortem studies of iRBD , and so there is virtually no bona fide case of idiopathic RBD .

7 The Concept of Prodromal RBD

Sixel-Döring and the Kassel Group [9, 21] have first observed short and often minor video events, called REM behavioral events (RBE) , in healthy persons or PD patients who did not yet fulfil the criteria of full-blown RBD [21], but subsequently developed full-blown RBD, and suggested the term prodromal RBD [9]. Based on EMG analysis, the Innsbruck Group showed that even REM sleep without atonia increases over time [10] and some of the patients who are above EMG thresholds for RBD diagnosis without meeting other RBD diagnostic criteria [40] will develop RBD in subsequent years [10].

Therefore the concept of prodromal RBD, based on video (≥2 REM behavioral events) and EMG (>32% of 3 s REM mini-epochs having any chin or phasic flexor digitorum superficialis activity), is now a solid concept based on two different pathways [8], as shown in Fig. 18.1 [8], and potentially very useful for future symptomatic or disease-modifying studies in RBD.

8 Questionnaires for RBD

A series of several specific questionnaires have been developed to screen for RBD. Their advantages and limitations are presented in detail in Chap. 19, by the Wing group. Questionnaires may be used to make a provisional diagnosis of RBD. PSG demonstration of RWA and any type of documentation of abnormal behaviors is necessary for the definite diagnosis or RBD, whereas questionnaires can only be used to make a diagnosis of probable RBD. Although most questionnaires showed excellent clinometric properties in their respective validation studies (see Chap. 19), subsequent use outside the strict context of validation studies has shown that the results are far less good and often problematic, and false positives and false negatives occur [8]. This has been recently confirmed in patients with da novo Parkinson’s diesase, wiht an AUC of 0.68 [41], as well as in the elderly Spanish community, with a positive predictive value of the used validated questionnaire of only 25% [42]. Therefore, the current role of questionnaires is seen as first screening step in a multistep procedure [43].

Conclusions

In summary, the importance of a correct diagnosis of RBD cannot be overemphasized, due to its implications for the individual patient with respect to the high risk for future emergence of neurodegenerative disease and also with respect for neuroprotective or disease-modifying treatment trials. While in past years it has become common knowledge that questionnaires alone are not suitable for RBD diagnosis, ongoing research is trying to identify screening methods for RBD [8]. Whether or not the diagnosis of RBD can be obtained in the future without PSG, perhaps based on novel technologies, remains to be established. At present, the diagnostic gold standard is PSG, including high-quality EMG recording from chin and upper extremity muscles.

References

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

Fernández-Arcos A, Iranzo A, Serradell M, Gaig C, Santamaria J. The clinical phenotype of idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder at presentation: A study in 203 consecutive patients. Sleep. 2016;39:121–32.

Fernández-Arcos A, Iranzo A, Serradell M, et al. Diagnostic value of isolated mentalis versus mentalis plus upper limb electromyography in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder patients eventually developing a neurodegenerative syndrome. Sleep. 2017;40. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx025.

Diagnostic Classification Steering Committee, Thorpy MJ, Chairman. International classification of sleep disorders: diagnostic and coding manual. Rochester, MN: American Sleep Disorders Association; 1990.

Schenck CH, Bundlie SR, Ettinger MG, Mahowald MW. Chronic behavioral disorder of human REM sleep: a new category of parasomnia. Sleep. 1986;9:293–308.

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders, revised: diagnostic and coding manual. Chicago: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2001.

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders: diagnostic and coding manual. 2nd ed. Westchester: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005.

Högl B, Stefani A, Videnovic A. Idiopathic REM sleep behaviour disorder and neurodegeneration—an update. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:40–55.

Sixel-Doring F, Zimmermann J, Wegener A, Mollenhauer B, Trenkwalder C. The evolution of REM sleep behavior disorder in early Parkinson disease. Sleep. 2016;39:1737–42.

Stefani A, Gabelia D, Högl B, et al. Long-term follow-up investigation of isolated rapid eye movement sleep without atonia without rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: a pilot study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:1273–9.

Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, et al. For the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. Version 2.4. Darien: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2017.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Iranzo A, Santamaria J. Severe obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome mimicking REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2005;28:203–6.

Gaig C, Iranzo A, Pujol M, Perez H, Santamaria J. Periodic limb movements during sleep mimicking REM sleep behavior disorder: a new form of periodic limb movement disorder. Sleep. 2017;40(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsw063.

Frauscher B, Iranzo A, Gaig C, et al. Normative EMG values during REM sleep for the diagnosis of REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2012;35:835–47.

Lapierre O, Montplaisir J. Polysomnographic features of REM sleep behavior disorder: development of a scoring method. Neurology. 1992;42:1371–4.

Zhang J, Lam SP, Ho CK, et al. Diagnosis of REM sleep behavior disorder by video-polysomnographic study: is one night enough? Sleep. 2008;31:1179–85.

Ferri R, Manconi M, Plazzi G, et al. A quantitative statistical analysis of the submentalis muscle EMG amplitude during sleep in normal controls and patients with REM sleep behavior disorder. J Sleep Res. 2008;17:89–100.

Frauscher B, Gschliesser V, Brandauer E, et al. Video analysis of motor events in REM sleep behavior disorder. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1464–70.

Frauscher B, Gschliesser V, Brandauer E, Ulmer H, Poewe W, Högl B. The relation between abnormal behaviors and REM sleep microstructure in patients with REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2009;10:174–81.

Sixel-Döring F, Trautmann E, Mollenhauer B, Trenkwalder C. Rapid eye movement sleep behavioral events: a new marker for neurodegeneration in early Parkinson disease? Sleep. 2014;37:431–8.

Santamaria J, Högl B, Trenkwalder C, Bliwise D. Scoring sleep in neurological patients: the need for specific considerations. Sleep. 2011;34:1283–4.

Frauscher B, Iranzo A, Högl B, et al. Quantification of electromyographic activity during REM sleep in multiple muscles in REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2008;31:724–31.

Frauscher B, Högl B. REM sleep behavior disorder. Discovery of REM sleep behavior disorder, clinical and laboratory diagnosis, and treatment. In: Chokorverty S, Allen RP, Walters AS, Montagna P, editors. Movement disorder in sleep. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. p. 406–22.

Ferri R, Rundo F, Manconi M, et al. Improved computation of the atonia index in normal controls and patients with REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2010;11:947–9.

Frandsen R, Nikolic M, Zoetmulder M, Kempfner L, Jennum P. Analysis of automated quantification of motor activity in REM sleep behaviour disorder. J Sleep Res. 2015;24:583–90.

Frauscher B, Gabelia D, Biermayr M, et al. Validation of an integrated software for the detection of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2014;37:1663–71.

Haba-Rubio J, Frauscher B, Marques-Vidal P, et al. Prevalence and determinants of REM sleep behavior disorder in the general population. Sleep. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx197.

Schenck CH, Bundlie SR, Patterson AL, Mahowald MW. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. A treatable parasomnia affecting older adults. JAMA. 1987;257:1786–9.

Manni R, Terzaghi M, Glorioso M. Motor-behavioral episodes in REM sleep behavior disorder and phasic events during REM sleep. Sleep. 2009;32:241–5.

Bugalho P, Lampreia T, Miguel R, Mendonça M, Caetano A, Barbosa R. Characterization of motor events in REM sleep behavior disorder. J Neural Transm. 2017;124:1183–6.

Stefani A, Heidbreder A, Brandauer E, et al. Screening for idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder: Usefulness of actigraphy. Sleep 2018;41(6). https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsy053.

Arnulf I, Uguccioni G, Gay F, Baldayrou E, Golmard JL, Gayraud F, Devevey A. What does the sleeping brain say? Syntax and semantics of sleep talking in healthy subjects and in Parasomnia patients. Sleep. 2017;40. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx159.

Rusz J, Hlavnička J, Tykalová T, Bušková J, Ulmanová O, Růžička E, Šonka K. Quantitative assessment of motor speech abnormalities in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder. Sleep Med. 2016;19:141–7.

Hlavnička J, Čmejla R, Tykalová T, Šonka K, Růžička E, Rusz J. Automated analysis of connected speech reveals early biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease in patients with rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder. Sci Rep. 2017;7:12.

Ferini-Strambi L, Di Gioia MR, Castronovo V, Oldani A, Zucconi M, Cappa SF. Neuropsychological assessment in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD): does the idiopathic form of RBD really exist? Neurology. 2004;62:41–5.

St Louis EK, Boeve AR, Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder in Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies. Mov Disord. 2017;32:645–58.

Iranzo A, Santamaria J, Tolosa E. Idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder: diagnosis, management, and the need for neuroprotective interventions. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:405–19.

Iranzo A, Stefani A, Serradell M, et al. Characterization of patients with longstanding idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology. 2017;89:242–8.

Sasai-Sakuma T, Frauscher B, Mitterling T, et al. Quantitative assessment of isolated rapid eye movement (REM) sleep without atonia without clinical REM sleep behavior disorder: clinical and research implications. Sleep Med. 2014;15:1009–15.

Halsband C, Zapf A, Sixel-Döring F, Trenkwalder C, Mollenhauer B. The REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Screening Questionnaire is not valid in de novo Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2018;5:171–6.

Pujol M, Pujol J, Alonso T, et al. Idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder in the elderly Spanish community: a primary care center study with a two-stage design using video-polysomnography. Sleep Med. 2017;40:116–21.

Postuma RB, Pelletier A, Berg D, Gagnon JF, Escudier F, Montplaisir J. Screening for prodromal Parkinson’s disease in the general community: a sleep-based approach. Sleep Med. 2016;21:101–5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Stefani, A., Frauscher, B., Högl, B. (2019). Diagnosis of REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. In: Schenck, C., Högl, B., Videnovic, A. (eds) Rapid-Eye-Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90152-7_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90152-7_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-90151-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-90152-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)