Abstract

Recent global historical cropland modelling grossly underestimates the pre-colonial development of agriculture in the Americas and many parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Such models are usually developed by back casting from recent land cover , combined with environmentally deterministic algorithms. Historical geographers have been slow in responding to a new demand for a global synthesis. In this paper, a preliminary map of African agricultural systems dating to AD 1800 is presented. It forms a component of the project Mapping Global Agriculture and is based on the existing historical literature, observations by early travelers, archaeology and archaeobotany . It should be emphasized that the generated map should be considered preliminary.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The 1992 special issue of Annals of the Association of American Geographers The Americas before and after 1492 (Butzer 1992) formed an important platform in the synthesis of pre-Columbian landscapes of America. With the completion of the three volume work on the cultivated landscapes of native America (Doolittle 2000; Denevan 2001; Whitmore and Turner 2001) and the subsequent dissemination of these syntheses to a broader audience in map form (Mann 2005), a new state of was research established, which had consequences more broadly for globally oriented historical geography. Because similar syntheses are lacking for the rest of the world, these research efforts represent a major challenge to historians, archaeologists and geographers working in other continents. Asia, with its long history of agriculture has some national agrarian histories, but no broader overview or any attempts at expressing agricultural history in map form. Similarly for Africa no synthesis of precolonial farming systems and agrarian landscapes has been published. Such empirically based global overviews of past land use and agriculture are badly needed to deal with some of the scientific challenges facing our world today. Within the humanities and the social sciences, the quest for understanding the globalized state we live in, fuels an inquiry into global production systems in existence prior to industrialization and western economic and political domination. Within climate science and global change studies, modelers use reconstructions of past land use in order to explain early human influence on the global climatic system. Both fields of research use old data—or in the case of climate modeling—replace data with assumptions. The work presented in this paper forms part of an effort towards answering these challenges. It presents a preliminary map of agricultural systems of sub-Saharan Africa for the cross-section AD 1800. It will be followed by cross-sections for AD 1000 and AD 1500 and forms part of a larger endeavor in producing a series of global maps for these three cross-sections.

PART I: Previous Research

The now well established relationship between vegetation, carbon cycles and climate has made knowledge of past agriculture a central focus in climate change research. It is increasingly recognized that early developments in land use have implications for the present day global climatic system. Since the publication of a seminal article by Ruddiman (2003), which addresses the role of early human land use on climate, historical aspects of land use have shifted increasingly into the focus of climate research. Ruddiman proposed that Neolithic farming as well as continued agricultural expansion well before the industrial revolution, had an impact on the emissions of greenhouse gases and the global climate system.

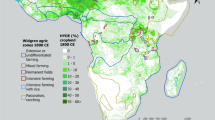

In the literature on long term carbon cycles and historical land use , different global models of past land use have been utilized. These are all based on back casting from recent land cover . The SAGE (Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment) dataset was initially published in 1999 and covered the period AD 1700–1999 (Ramankutty and Foley 1999). At the same time HYDE (History Database of the Global Environment) was established and initially also covered the past 300 years (Goldewijk 2001). Pongratz et al. (2008) published a series of maps covering AD 800–AD 2000. All are based on recent global distribution of croplands, from which cropland distribution in previous centuries are calculated based on historical population estimates.

HYDE is now the most commonly used and quoted model of past croplands. The recent version covers the last 12,000 years (Goldewijk et al. 2011). The basic assumption behind the HYDE model is that past agriculture developed within the confines of the recent distribution of croplands and successively expanded to fill these areas. Allocation of historical cropland between recent state territories (and in some cases between regions within states) is made in relation to historical population estimates (McEvedy and Jones 1978, with some recent updates) and an assumption on cropland per capita. The distribution within these geographical territories is based on algorithms and weighting maps which take into consideration among other things soil suitability for crops according to recent FAO maps of global agro-ecological zones. In addition, coastal areas and river plains are given positive weight and steep terrain is given negative weight. Historical data on agricultural history and cropland distribution are not entered into this weighting model. The location and extent of historical cropland reconstructions can only be changed by different population estimates, different per capita assumptions or different assumptions on how environmental variables impact on location of croplands. The results of such modeling are presented as “datasets” and used widely in climate modeling. But their connection to actual empirical data of settlement and land use in the past is weak. When they, as Goldewijk et al. (2011), claim to depict the distribution of croplands and pasture in distant archaeological past periods, they are profoundly misleading.

However, there are alternate approaches that are empirically based. Three different methods of land cover reconstructions based on data, instead of modeling, can be identified. First, in areas with reliable historical sources, this information can be used to reconstruct detailed gridded cropland maps for different historical periods. Chinese historical geographers are at the forefront of this approach and have published gridded maps of croplands of the mid-northern Song Dynasty (AD 1004–1085, He et al. 2012). Similar methods have been developed for Scandinavian countries, but they will not be able to reach further back than the 16th century (Li et al. 2013).

A second approach is through the quantitative treatment of pollen data (e.g. Gaillard et al. 2010). Pollen percentages over time are recalculated to classes of land cover . There are in principle no restrictions in the regional or chronological reach of such pollen based approaches, but the work necessary to achieve a global synthesis is extensive.

A third approach is represented by the mapping of global agrarian systems rather than precise land use and land cover . During the first part of the 20th century, several attempts were made by geographers to move beyond the mere mapping of agro-climatic zones, towards a more substantial understanding of different types of agriculture , which takes into account not only various environmental conditions, but also different historical pathways that agriculture has taken in different regions (see e.g. Whittlesey 1936). Grigg’s (1969) theoretically informed review and his reflections on previous work on agricultural regions, along with his subsequent book (Grigg 1974) on the agricultural systems of the world, are still fundamental to any work on the history of global agriculture . Neither Whittlesey nor Grigg formulated their respective regionalizations based on one main simple classificatory characteristic, such as crops, tools or nutrient circulation. In Griggs words we are thus dealing with multi-purpose regions rather than single purpose regions. Although Grigg in a previous paper discussed regionalization as a formal and rigorous process (Grigg 1965), in the case of global agrarian systems he realized the process had to be intuitive (Grigg 1969). Grigg’s work was mainly based on and developed further the map presented by Whittlesey (1936). With different updates and alterations it remains to this day one of the most reproduced maps of global agricultural systems . The Whittlesey map, representing the beginning of the 20th century is a natural conceptual and empirical starting point for a retrogressive historical analysis of global agriculture . Whittlesey emphasized five aspects in his classification of global agricultural regions: “1. The crop and livestock association. 2. The methods used to grow the crops and produce the stock. 3. The intensity of application to the land of labor, capital, and organization, and the outturn of product which results. 4. The disposal of products for consumption. 5. The ensemble of structures used to house and facilitate the farming operations.” (Whittlesey 1936:209)

Based on Whittlesey’s map and the modifications made to it by subsequent writers, Grigg (1974) identified the following categories: 1. shifting agriculture ; 2. wet rice cultivation in Asia; 3. pastoral nomadism ; 4. Mediterranean agriculture ; 5. mixed farming in Western Europe and North America; 6. dairying; 7. the plantation system; 8. ranching; and 9. large scale grain production.

Mapping Global Agricultural History

The approach taken by Whittlesey and Grigg forms the basis for the work reported in this paper. The goals, categories and methods were developed by a small group of historians and historical geographers in Sweden and the US in the collaborative project Mapping Global Agricultural History. The project aims at summarizing the existing knowledge of land use and agricultural regions on a global scale during the last millennium (Widgren 2010a). The design, as well as the proposition of global categories of agricultural regions, is the result of a collective effort by this group.Footnote 1 The map I present here is the first in a series of three maps AD 1000, AD 1500 and AD 1800, which will be included in a forthcoming global map of agricultural regions. The Mapping Global Agricultural History project now also forms part of a wider program studying land cover changes during the last 6000 years on a global scale (LANDCOVER6K, Gaillard 2015) supported by the PAGES (Past Global Changes) network and involving all approaches mentioned above including a large group of paleo-ecologists, archaeologists, historians and historical geographers as well as modelers active in this field.

A central aim of the Mapping Global Agricultural History project is to express current knowledge of global agrarian history on maps, in a format that can be compared with and challenge maps based on back-casting. The project will produce a series of maps of global agricultural systems during the last millennium at the same level of detail and scale as the map of Whittlesey (1936). Three cross-sections have been selected: (1) AD 1000 which was a time when especially African and American polities and landscapes were distinctly different from those of the late fifteenth century; (2) AD 1500, on the eve of European oceanic expansion and before the Columbian exchange; and (3) AD 1800, before the nineteenth-century wave of globalization that drew large parts of the global South into commercial agriculture .

There is one important difference between our approach and the above mentioned parallel efforts to reconstruct land cover . We do not map land cover , but a series of qualitatively different agricultural regions. We map the presence of agriculture in a region during a specific time-window, and characterize the dominant type of agricultural system in that region. It is therefore not possible to directly translate these maps to areas of different land cover or land use . However, as will be shown below, we characterize agricultural systems on a scale of intensity which facilitates comparison with other methods.

Global Categories

The selection of categories of agricultural regions to be displayed on a global map is, as is always the case with regionalization, a compromise. In our categories, we have drawn on both Whittlesey (1936) and Grigg (1974), with the three first criteria used by Whittlesey as the starting point. Criterion four was excluded, because in the longer time perspective that we take into consideration, the degree of commercialization is considered to have been low. Before the mid-19th century AD global land use was not characterized to same extent by global flows of food and fibers. Moreover, recent research in historical and economic anthropology has come to question the idea of pure subsistence farming, as most agricultural communities produced a surplus and were involved in exchange with other groups (Håkansson 1994:249–251, 2008:240–242, 248–252). Similarly we have not considered Whittlesey´s fifth aspect, the structures to house and facilitate farming operations, because we do not have global data on this subject for earlier periods. The categories in Grigg (1974) that refer to commercial agriculture typical of the late 19th and the 20th century, including specialized dairying (6), plantations (7) and large scale grain production (9), have been excluded and instead we have added categories more relevant for the preindustrial period.

Agricultural systems can be considered as qualitatively different ways of utilizing the land and they do not immediately translate to any quantitative measure, or to any simple evolutionary sequence. For that reason, most maps of agricultural regions use a nominal scale, with map signatures that are qualitatively different but not in any quantitative order. However, systems do differ in the degree of intensity (for different aspects of intensity see below). In order to make our maps more legible and comparable with other maps of historical croplands , we have used a combination of nominal and ordinal scales.

We have therefore made an attempt at ranking degrees of intensity from husbandry of non-domesticated plants and pastoralism, to extensive farming, permanent fields and to more intensive forms of agriculture involving modification of soils through manuring and major landscape transformations, such as terracing, canal irrigation and dykes. The measure of intensity in Table 1 is of course a very rough estimate. In reality, we are dealing with at least three different ways of expressing intensity. First, of interest for agrarian history and for understanding the possibilities of producing a surplus, input and output per hectare are central measures. In our categories, we first consider labor intensity, i.e. input of labor per defined areal unit. Secondly, taking a landscape perspective, the degree to which the land has been modified (anthropogenic soils, irrigation, terracing etc.) can also be classified into varying intensities. Thirdly, for comparison with other land cover maps, the density of cropland (for example hectares of cropland per square kilometer) would have been the best measure of intensity. However, the map basically describes dominant agricultural systems in each region and this measure of intensity cannot always be read from the maps. The intensity of fields on the ground can differ significantly within otherwise homogenous agricultural regions. To take an example from the forthcoming global map: mixed farming existed historically in the Paris basin, as well as in the central forested parts of Scandinavia. Differences in the density of croplands versus meadows, grazing land and forests, would have been obvious in this vast region. In our very cursory indication of intensity in Table 1 and as reflected in the color sequence on the global map we have ranked, on a very general level, the combined intensity, taking into consideration the three aspects mentioned above.

A specific region is often characterized by a mosaic of different forms of agriculture and pastoralism. Especially at the intermediate level of intensity (rank 5 in Table 1) agriculture has been characterized by regionally distinct forms of farming, which combined extensive and intensive methods in the same area. The Mediterranean agriculture with its intensive irrigation and horticulture, grain-fields with winter crops, and at the same time extensive transhumance exemplifies such a mosaic. In order not to reduce agricultural history to just a linear development towards more intensive agriculture , but to give weight to regional diversity, we allowed for a limited number of regionally distinct forms of such mosaics or agricultural complexes to be represented on the map.

In the global map that we have prepared, eleven broad categories are used on a preliminary basis. Some of them are not represented in sub-Saharan Africa. However, some of the global categories can, for the purpose of the African map, be further subdivided. Table 1 presents the global categories and subdivisions that are possible and relevant for Africa.

Sources and Methods

Syntheses of African farming taking a long term perspective have, to a large extent, focused on the introduction and spread of farming, and to a lesser degree on the changes in tools, crops, field systems and farming practices during subsequent periods (see Sutton 1996; Fuller and Hildebrand 2013; Gifford-Gonzales and Hanotte 2011, 2013; Russell et al. 2014). For a general understanding of the diversity of pre-colonial agriculture on the continent the works of William Allan (1965) and Marvin Miracle (1967) do provide an important starting point. Since then, several studies have demonstrated how innovative and ecologically aware many local agricultural systems were and often remain so in the present. But as the contrasting perspectives of Kjekshus (1977) and Koponen (1988) do show, there is indeed an intellectual and empirical endeavor to move from a general appreciation of the diversity and ingenuity of precolonial agriculture towards a chronologically rich and precise articulation of agrarian history. The special issue of Azania Towards a history of cultivating the fields is an important milestone in the study of precolonial African field systems (Sutton 1989). Some works take a broad view of the agricultural history of particular areas (David 1976; Blench 1997; McCann 1995) but for the whole continent, no grand syntheses are published. Blench (2006) contributes important syntheses towards an agrarian history of Africa. Studies that document a clear regional sequence of agricultural change during the last millennium, however, remain few in number.

Earlier writings sometimes confuse the 19th and 20th century ethnographically-documented African farming practices with what existed in the more distant past, and assume an almost essentialist connection between ethnic groups and their systems of agriculture (see, for example, Beck 1943). But agriculture developed in Africa as it did elsewhere and there are indeed regional works on agrarian history based on oral history and early travelers, which focus directly on this change and challenge and go beyond simplistic assumptions of inertia in agricultural development (see e.g. von Oppen 1993; Cochet 2001; Hawthorne 2003). Such regional studies of agricultural change permit the production of a credible delimitation on a map.

When previous authors have expressed their research on agrarian systems in map form, as is the case e.g. for the permanent fields in the Congo basin (Vansina 1990), this information has been included in our AD 1800 map. Also when the distribution of ancient and abandoned field system is known and archeologically dated, as is the case for Bokoni and Nyanga in Southern Africa, delimitation of these features on a map is uncontroversial. In other cases the characterizations and delimitations of the regions on a map are based on a combination of more recent ethnographic observation of agricultural systems , supported by scant contemporary evidence from travelers’ reports from the early to late 19th century AD. Such reports seldom include general characterizations of types of farming, but they can nevertheless, in their detailed observations of crops and work on the fields, be used to lend support to the conclusion that a similar agricultural system existed already by 1800 AD. In a few cases analogous reasoning and informed guesses have also been used. This has been done in the case of dating the Mossi infield-outfield system (see below) and terraced highland areas in Western Africa (cf. Widgren 2010b).

A problem with the map of AD 1800 for Africa is that the 19th century was a dynamic period. In some case what was observed on the ground in the mid-19th century may have been developed shortly before that as the result of, for example, expanding caravan trade in eastern Africa (e.g. the Baringo canal irrigation system—see below under 6.1). In other cases, such as in the abandonment of field systems at Engaruka in Tanzania and Nyanga in Zimbabwe, AD 1800 represents the latest possible, but not yet fully proven, date of its abandonment. As such the dating of the map to AD 1800 should be considered an estimate and not exact. Moreover, it must be said that in Africa many non-tangible components of agricultural systems have evaded documentation, aspects which have been well recorded in Europe, India and China, with their extensive literature on agrarian history. Such information that is lacking for Africa includes yield ratios, productivity, cropping sequence and knowledge systems. There is always a danger that spectacular landscape modification, visible as archaeological features and notable farming methods observed by travelers, take a more important role than daily activities of the knowledgeable women and men that shaped the agriculture of Africa (cf. the “tyranny of monuments” Sutton 1989:112).

PART II: Agricultural Systems by AD 1800

At a general level there was a close relation between climatic zones and agricultural regions (Fig. 1). In the mainly semi-arid savanna zones (“arid steppe”) grain-based farming of sorghum and millets dominated and was interspersed with pastoralism. In contrast, cattle was absent in equatorial climatic zones and cultivation was based either on a combination of grain and roots/tubers or (especially in the fully humid or monsoonal equatorial climate zones) a vegeculture complex based on roots, tubers and bananas. In temperate highland zones (“warm temperate”) we find many different examples of more intensive agriculture with mixed farming, terracing and, as in the highlands of Madagascar, paddy rice cultivation. However, the map (Fig. 2) will also show many exceptions, where areas of mixed farming or irrigation existed as islands in more intensive agriculture within the arid steppes.

Main climatic zones with a selection of places and regions mentioned in the text. The climate zones follows the updated Köppen-Geiger classification (Kottek et al. 2006) and is for the purpose of this map divided into five classes: Desert (BW), steppe (BS), warm temperate (C), equatorial with dry winter or dry summer (As and Aw) and equatorial fully humid or monsoonal (Af and Am).

The map presented here (Fig. 2) is an attempt at visualizing our present knowledge of late precolonial African agricultural systems . The starting point has been the global categories as described in Table 1. The following categories can be inferred from the sources described above.

Pastoralism and Ranching

Areas dominated by specialized pastoralism, where cultivation was of minor importance, have fluctuated in extent over time in Africa. It is a difficult task to clearly delimit areas where such specialized pastoralism was prevalent. The boundary between extensive cultivation and pastoralism has been fluid over time and, moreover, most areas of extensive cultivation in the savanna zones were also interspersed with pastoralism. Especially difficult is eastern Africa, where rainfall is highly variable within short distances and the result is a complicated mosaic of semiarid, temperate and equatorial climates (cf. Fig 1, or the more detailed map by Pratt and Gwynne reproduced in Håkansson 2004:579). Specialized pastoralism expanded in this area during the 18th and 19th centuries AD (Bollig et al. 2013), but there have been only a few attempts to map these changes (Sutton 1993; Håkansson 2012). The boundary between pastoralism and farming as depicted on this map (Fig. 2) must therefore be used with caution, especially in eastern Africa. More work is needed to make a sharper delimitation of the extent of pastoralism in AD 1800.

Husbandry of Non-domesticated Plants

On global maps, the category husbandry of non-domesticated plants will be used in areas of the world where the protection, encouragement and planting of non-domesticated plants constituted the main plant-based activities and where pastoralism or cultivation of domesticated plants were not practiced. Such activities probably were present among many hunter-gatherers. In Africa, husbandry of non-domesticated plants is documented, e.g. in the Congo rain forest (Yasuoka 2013), but because this was practiced in pockets within larger regions dominated by extensive agriculture , no attempt has been made to map them at this scale.

Extensive or Undifferentiated Agriculture

This somewhat clumsily named category refers to, on the one hand, areas where agriculture is known to have been extensive (e.g. slash-and-burn), and on the other hand to areas where agriculture existed, but its character is unknown. It was important in this context and in comparison with non-historical modeling to show the full extent of farming on the AD 1800 map, even when its nature is not fully understood, rather than to mark these areas as “no data”.

There is tendency among researchers to assume that shifting cultivation was the norm for all early agriculture . In this project, a more conservative standpoint is taken and hence the same degree of proof for shifting cultivation has been required as for intensive farming systems. With better evidence from paleoecology there are now some regions in Africa that have provided direct evidence that fields were shifting, fire was used regularly, and the vegetation was characterized by secondary woodlands, but such direct evidence is still scarce (Höhn and Neumann 2012).

Within the area delimited as extensive or undifferentiated agriculture there is scattered evidence from the 18th and 19th centuries AD for intensive farming methods. This includes the case of mounding and ridging in the upper Zambezi valley (Almeida et al. 1873:92; von Oppen 1993:108ff) and the use of manure in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa (Beck 1943). But in these and other cases, neither the full character of the agricultural system nor its definite delimitation has been possible to document at this stage. Another important aspect of this category is the role of tree crops and the specific form of agricultural landscapes characterized by parklands with extensive grain cultivation. This type of agrarian system and its resulting clearly anthropogenic landscape has not been mapped here. Overviews of present parklands exist (Boffa 1999), but to my knowledge, their historical depth has not yet been mapped on regional scale.

Evidence from the 20th century AD shows that the term shifting cultivation in sub-Saharan Africa comprises a large array of different types of farming (cf. the map by Morgan 1969:252–253), but at this point such evidence for the precolonial period is not at hand. Another important distinction within this larger region is the division into areas dominated by different staples: vegeculture (roots and bananas) mainly in regions of equatorial climate and grain in savanna regions. Large areas where grain and roots were intermixed also existed. We know now that this division was not fixed, and not fully determined by climate, but that it changed over time (Kahlheber et al. 2013). The arrival of American crops to Africa expanded the crop repertoire within the vegeculture complex with cassava and sweet potatoes. The introduction of maize may have opened up more humid environments for grain cultivation. The effects of these new arrivals on the zoning of vegeculture versus grain cultivation have not yet been documented.

In the AD 1800 map presented here (Fig. 2), the regions of main staples as described by Morgan for the 20th century (1969:252–253) are shown stippled and hatched on top of the main category of extensive or undifferentiated farming. Morgan’s zones roughly correspond to maps presented by Harris on West African traditional crop zones (Harris 1976: Fig. 4) and the map for the Congo basin by Marvin Miracle on principal food crops in the Congo basin 1900–1915AD (Miracle 1967:281). Extending the mid-20th century AD distribution back in time to AD 1800 is hypothetical but mapping that distribution may form a basis for further research.

The outer limits of this agricultural region also correspond to the limits of agriculture at this time. The northern boundary is based on the more recent evidence from Dixon et al. (2001) with some consideration also taken of the limits of agriculture in different countries as documented in L’atlas de l’Afrique (Ben Yahmed and Sablayrolles 2000). The southern limit roughly follows Russell et al. (2014) and for South Africa the more precise limits of African farming settlements as documented by Maggs (1980, 1984).

Permanent Fields on Dry Lands

In many parts of Africa, fields were more or less permanent. This does not exclude periods of fallowing, but farming was permanent enough for regular field systems to develop. There is also archaeological evidence of permanent field systems in arid regions as in Tagant in Mauretania and in the Niamey region in Niger (Khattar et al. 1994; Khattar 1995; Guillon et al. 2013), but it is not clear whether they survived into the 19th century AD and therefore they are not represented on this map.

Several areas in present day Tanzania, often at the junction of important 19th century AD caravan routes, were described by Gillman (1936:361) as ‘cultivation steppes’ (see also Håkansson and Widgren 2007). The evidence from Stanley’s journey through Ugogo and neighboring areas is in line with this characterization (Stanley 1872). Some of the areas in the Kenyan highlands, inhabited by the Kikuyu, the Meru and the Embu, do belong to this category (Table 2, Fig. 3). Their role as specialized grain producers is evidenced in the regional economic history of Ambler (1988) and the travel accounts of Gedge (1892) give an impression of some densely cultivated landscapes, albeit in a later period. These areas are marked as permanent fields on the AD 1800 map. Most likely many other areas in sub-Saharan Africa shared this characteristic, but the evidence has not yet come to light.

Agricultural systems . Red figures refer to Table 2.

Flood Retreat and Other Wetland Cultivation

In the global map, flood retreat farming and other types of wetland cultivation will be classified as a subcategory of permanent fields. Wetland cultivation forms an important part of African agricultural systems (for details and distinctions between crue, décrue and other wetland cultivation techniques see Marzouk 1989 and Adams 1991:76ff). The reason for making a clear difference between this type of wetland cultivation and irrigated agriculture is that the degree of landscape modification was low or non-existent in ordinary flood retreat farming in contrast to irrigated agriculture , where the building and repair of dykes and canals are central activities and accordingly labor intensity is higher.

The Inland Niger Delta forms the largest concentrated area for flood recession agriculture in Africa which is evidenced in the 19th century AD by Caillié (1830a) and Barth (1858). Similar farming was practiced along many rivers and lake shores in other parts of Africa. I have restricted the cases presented on the map to the few instances where I have found clear evidence that it was practiced in the early 19th century AD. Marzouk (1989) provides evidence for several other areas, in which the history is however not known. Caillié who travelled in West Africa in the 1820s does not explicitly note décrue cultivation in the Senegal River , but he describes it in detail on the shores of Lake Aleg and also for the area in more general terms (Caillié 1830b). The cultivation of sorghum on the shores of Lake Chad is described by Denham et al. (1826). In eastern Africa there is evidence for early 19th century AD wetland cultivation along the Omo River (Bassi 2011), the Tana River (Ylvisaker 1979) and in the Kilombero and Rufiji deltas (Monson 1991; Havnevik 1993; Beez 2005).

Present and past farming in the Inland Niger Delta has usually been described as flood retreat rather than irrigation. A few dykes and drainage ditches are however reported by travelers in the 19th century AD (Barth 1858:150, 157, 224; Caillié 1830a:136). It is notable that Pierre Viguier writes that he himself, in contrast to Caillié, has not seen any trace of hydraulic management during his long observation and studies of the rice cultivation in the Inland Niger delta in the 20th century AD (Viguier 2008). Viguier’s short remark is important since it opens for the question to which degree hydraulic management, landscape modifications and a more labor intensive agriculture might have been more common before the colonial period in this area. Observations of dykes were also made in the 19th century AD in the lower reaches of Tana River in present Kenya (Ylvisaker 1979:56).

Mixed Farming

Many precolonial farming systems in Africa showed a high degree of integration between the livestock and arable fields. Manure was used as fertilizer, and products from the fields were used as fodder for livestock. In the AD 1800 map, the term mixed farming is used for these types of systems. A technical definition of mixed farming formulated in the context of the propagation of mixed farming to Africa is the following: “… mixed farming is the cultivation of crops and the raising of cattle, sheep and/or goats by the same economic entity, such as a household or a ‘concession’, with animal inputs (e.g. manure, draft power) being used in crop production and crop inputs (e.g. residues, fodder) being used in livestock production” (Powell and Williams 1993).

In the African context the term mixed is farming is often connected to a development agenda in which the “modern” methods of farming that were developed during the agricultural revolution in Western Europe were exported to Africa in the 20th century. As with many other terms for agricultural systems the concept is thus tainted by its specific usage in development discourse (cf. the discussion of the concept as used in Zimbabwe in Wolmer and Scoones 2000). It can therefore be questioned if such a term based on a European perspective should be used as a generic and globally applicable concept. Except for the issue of draft power, which during this period in sub-Saharan Africa only existed in highlands of the Horn of Africa, mixed farming in the sense of the quoted definition was already present on the continent long before it became a part of part of a development agenda. I cannot find a better term than mixed farming to describe this farming system. On the map I have identified the following different subcategories of mixed farming in sub-Saharan Africa.

Mixed Farming: Infield-Outfield Systems

Sautter has provided a comprehensive overview of infield-outfield systems in West Africa (Sautter 1962). They combined an intensively cultivated and manured infield, immediately surrounding the village or town, with an extensively cultivated outfield, which received no or little manure. In some cases the infield only consists of small gardens such as in Fouta Djallon. These systems have also been termed ring-cultivation systems (see Widgren 2012, 2017 and references cited there). The argument that such systems, which are documented among the Serer in Senegal, in Fouta Djallon, among Mossi in Burkina Faso and in Hausaland, were already well developed in the early 1800s AD is based on observations by Caillié (1830a, b), Denham et al. (1826) and other travelers as well as the historical analysis of Watts (1983) for Hausaland and the retrogressive analyses of Pélissier (1966) on the Serer. The close integration between crop and livestock in that area may go back to the thirteenth century when the Serer first settled in the area (Reinwald 1997). In the Mossi area such farming systems have been documented mainly in the 20th century AD by early travelers and later researchers (Prudencio 1993; Stamm 1994 and references therein). The conclusion on Mossi is thus based on analogy, for lack of direct evidence.

Mixed Farming, General

The mixed farming systems of northern Europe (and in the development agendas) included the use of oxen as draft power and the use of ploughs. But in sub-Saharan Africa plough agriculture was by AD 1800 more or less restricted to the highlands in the Horn of Africa and as McCann (1995:42) has shown it was by then mainly restricted to areas north of 9 degrees latitude. Only later did it spread to almost all highland areas in Ethiopia . The integration of livestock and agriculture was in this area mainly restricted to draft power, and to a lesser degree based on the use of manure as fertilizer on agricultural fields (McCann 1995:57). In large areas of the highlands terracing was common, but I have not been able to find a good overview of the historical situation (for later periods see Tadesse et al. 2006:86).

Beck (1943) provides a map of areas where manure was used according to different sources from the 19th and 20th century AD, but it is difficult to pinpoint the delimitation of specific agrarian systems and their dates. Outside the areas of infield-outfield farming and the areas where manuring was combined with extensive terracing (see below), it is mainly from the evidence of Kjekshus (1977) for Tanzania and Cochet (2001) for Burundi that it can be argued that a fully-fledged mixed farming existed in the early 19th century AD.

Mixed Farming with Terracing

A detailed overview of intensive and terraced agriculture in West Africa and Sudan and a discussion of the chronology of these systems can be found in Widgren (2010b). For eastern Africa Widgren and Sutton (2004) provide an overview. The mapped occurrences in eastern Africa are based on the Iraqw of Tanzania (Börjeson 2004) and the Konso-Burji complex in Ethiopia (Amborn 2009; Watson 2009). The occurrences of abandoned terracing in Southern Africa are based on recent archaeological research in Nyanga and Bokoni (Soper 2002; Delius et al. 2014; Widgren et al. 2016).

Intensive Systems

Whittlesey (1936) identified a category termed Intensive subsistence tillage without paddy rice. In Africa for AD 1800 intensive systems is used for systems that had clearly higher productivity per area than most other categories, except the irrigated rice (see below).

Intensive Systems: Banana Gardens

By AD 1800 the banana gardens of interlacustrine Africa had not yet reached their full extent, with, for example, Burundi still dominated by a maize system with mixed farming (Cochet 2001). The expansion of banana cultivation in the interlacustrine area and in Uganda has been described by Schoenbrun (1998:79ff) and Reid (2001). In the highlands of Meru, Kilimanjaro and in the eastern arc mountains of Tanzania, home gardens with bananas were already established at this time and based on canal irrigation (Stump and Tagseth 2009).

Intensive Systems: Canal Irrigation

Specialized canal irrigation complexes focusing on grain were found in the Marakwet and Engaruka-Sonjo-Pagasi complex (Berntsen 1976; Adams et al. 1994; Östberg 2004; Stump 2006; Davies et al. 2014), in the Mbooni hills in Kenya (Jackson 1976) and the Uluguru mountains in Tanzania (Kjekshus 1977:36; Paul 2003:71). By AD 1800 it is possible that the now defunct system at Engaruka was still in active use (Westerberg et al. 2010), and although questions have recently been raised on the antiquity of the Marakwet, it remains probable that the irrigation in Marakwet was already developed (Davies et al. 2014). The canal irrigation system at Baringo in Kenya developed later in the 19th century AD and is therefore not included in this map (Anderson 1988, 1989; Petek and Lane 2017).

Irrigated Rice

The expansion of the irrigated paddy rice complex of West Africa is described and discussed in the works of Carney (2001), Hawthorne (2003) and Fields-Black (2008). The conclusions there are partly contradictory as to the early history of irrigated rice in the mangrove areas, but the distribution by 1800 AD seems uncontroversial. The irrigated rice cultivation in Madagascar saw its start in the 1600s AD and its growth was closely connected to the Merina kingdoms (Campbell 2005). The detailed reconstruction of the transformation from extensive swidden rice cultivation to the establishment of irrigated rice cultivation of the highlands, with extensive landscape modification in the form of dykes, canals and terracing is mapped by Le Bourdiec (1974) based on early travelers accounts.

Summary and Discussion

The purpose of this paper has been to map the distribution and character of agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa at approximately 1800 AD. As can be seen from the map (Fig. 2), it has been possible to delimit a series of qualitatively different agricultural systems for that period mainly in Western and Eastern Africa. Large parts of Central and Southern Africa provide a much more homogenous picture. With few exceptions, this vast region of Africa exhibits variation only in the different staple crops under cultivation. It must be noted that these boundaries are hypothetical and based mainly on data which are some 150 years later than 1800 AD. It is of course unlikely that this large region was so homogenous. Evidence exists for differentiated, and sometimes more intensive farming methods, but it has not been possible to delimit larger regions. The evidence from early travelers is not systematically used all over Africa and it is likely that more work based on these sources will improve the map, especially in Central and Southern Africa. The systematic use of archaeological databases may also substantially improve the data for this vast region. Such work for Africa is now planned within the framework LANDUSE6K (http://landuse.uchicago.edu).

It is both a weakness and strength to summarize scanty evidence in map form. While a written synthesis can omit areas with no or little evidence, the map exhibits openly its weaknesses which become more transparent. Many readers will immediately see problems in the map, based on their specific regional knowledge, which will hopefully provoke responses and critique. In order to facilitate critique and scrutiny of the inference from the literature to the polygons as depicted on the maps, a downloadable GIS-file lists the main sources for each region. Table 2 is based on the GIS file and should be read together with Fig. 3. Comments, criticism and additions are more than welcome and may be incorporated into later versions of the map.

Notes

- 1.

Ulf Jonsson (Stockholm University), Janken Myrdal (Swedish University Agricultural Sciences), William E. Doolittle (University of Texas, Austin), Mats Widgren (Stockholm University) and William I. Woods (1947–2015, University of Kansas).

References

Adams WM (1991) Wasting the rain: the ecology and politics of water resources in Africa. Earthscan, London

Adams WM, Potkanski T, Sutton JEG (1994) Indigenous farmer-managed irrigation in Sonjo, Tanzania. Geogr J 160:17–32

Ajayi JFA, Crowder M, Coquery-Vidrovitch C, Laclavère G (1988) Atlas historique de l’Afrique. Les Editions du Jaguar, Paris

Allan W (1965) The African husbandman. Oliver & Boyd, Edinburgh

Almeida FJM, de Lacerda E, Burton RF et al (1873) Lacerda’s journey to Cazembe in 1798. John Murray, London

Ambler CH (1988) Kenyan communities in the age of imperialism: the central region in the late nineteenth century. Yale historical publications. Miscellany, vol 36. Yale University Press, New Haven

Amborn H (2009) Flexibel aus Tradition: Burji in Äthiopien und Kenia. Unter Verwendung der Aufzeichnungen von Helmut Straube. With explanation of some cultural items in English. Aethiopistische Forschungen, vol 71. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden

Anderson DM (1988) Cultivating pastoralists: Ecology and economy among the Il Chamus of Baringo, 1840–1980. In: Johnson D, Anderson DM (eds) The ecology of survival: case studies from Northeast African history. Crook, London, pp 241–260

Anderson DM (1989) Agriculture and irrigation technology at Lake Baringo in the nineteenth century. Azania 24:89–97

Barth H (1858) Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa: being a journal of an expedition undertaken under the auspices of H. B. M.’s government, in the years 1849–1855, vol. 5. Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, Roberts, London

Bassi M (2011) Primary identities in the lower Omo valley: migration, cataclysm, conflict and amalgamation, 1750–1910. J East Afr Stud 5(1):129–157

Beck WG (1943 (reprint 1968)) Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte der afrikanischen Feldarbeit, Stuttgart 1943. Repr. Johnson Reprint, New York, NY, London (tr. Meisenheim (Glan))

Beez J (2005) Die Ahnen essen keinen Reis: Vom lokalen Umgang mit einem Bewässerungsprojekt am Fuße des Kilimanjaro in Tansania. Universität Bayreuth, Bayreuth

Ben Yahmed D, Sablayrolles J (2000) L’atlas de l’Afrique. Jaguar, Paris

Berntsen JL (1976) Maasai and their neighbors: variables of interaction. Afr Econ Hist 2:1–11

Blench RM (1997) The history of agriculture in northeastern Nigeria. In: Barreteau D, Dognin R, von Graffenried C (eds) L’Homme et le milieu végétal dans le Bassin du Lac Tchad. Orstom, Paris, pp 69–112

Blench RM (2006) Archaeology, language, and the African past. AltaMira Press, Lanham

Boffa J-M (1999) Agroforestry parklands in Sub-Saharan Africa. FAO, Rome

Bollig M, Schnegg M, Wotzka H-P (2013) Pastoralism in Africa: past, present and future. Berghahn Books, New York

Börjeson L (2004) A History under Siege: intensive agriculture in the Mbulu Highlands, Tanzania, 19th century to the present. Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, Stockholm

Butzer KW (1992) The Americas before and after 1492: an introduction to current geographical research. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 82(3):345–368

Caillié R (1830a) Journal d’un voyage a Temboctou et a Jenné dans l’Afrique centrale précéde observations faites chez les maures braknas, les nalous et d’autres peuples; pendant les années 1826–1828 T. 2. Imprimerie royale, Paris

Caillié R (1830b) Journal d’un voyage a Temboctou et a Jenné dans l’Afrique centrale précéde observations faites chez les maures braknas, les nalous et d’autres peuples; pendant les années 1826–1828 T. 1. Imprimerie royale, Paris

Campbell G (2005) An economic history of Imperial Madagascar 1750–1895: the rise and fall of an island empire. African studies series, vol 106. Cambridge University Press, New York

Carney JA (2001) Black rice: the African origins of rice cultivation in the Americas. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Christopher AJ (1982) Towards a definition of the nineteenth century South African Frontier. S Afr Geogr J 64(2):97–113

Cochet H (2001) Crises et révolutions agricoles au Burundi. Karthala, Paris

David N (1976) History of crops and peoples in North Cameroon to A.D. 1900. In: Harlan JR, De Wet JMJ, Stemler ABL (eds) Origins of African plant domestication. Mouton, The Hauge, pp 223–268

Davies MIJ, Kipruto TK, Moore HL (2014) Revisiting the irrigated agricultural landscape of the Marakwet, Kenya: tracing local technology and knowledge over the recent past. Azania 49(4):486–523

Delius P, Maggs T, Schoeman A (2014) Forgotten World: the stone walled settlements of the Mpumalanga Escarpment. Wits University Press, Johannesburg

Denevan WM (2001) Cultivated landscapes of Native Amazonia and the Andes: triumph over the soil, Oxford geographical and environmental studies. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Denham D, Oudney W, Clapperton H (1826) Narrative of travels and discoveries in Northern and Central Africa, in the years 1822, 1823 and 1824, by Major Denham, F.R.S., Captain Clapperton, and the late Doctor Oudney, vol I, 2nd edn. John Murray, London

Dixon J, Gulliver A, Gibbon D (2001) Farming systems and poverty: improving farmers’ livelihoods in a changing world. FAO, Rome

Doolittle WE (2000) Cultivated landscapes of native North America. Oxford geographical and environmental studies. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Fields-Black EL (2008) Deep roots: rice farmers in West Africa and the African diaspora. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

Fuller DQ, Hildebrand E (2013) Domesticating plants in Africa. In: Mitchell P, Lane P (eds) The Oxford handbook of African archaeology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 507–526

Gaillard MJ, Sugita S, Mazier F et al (2010) Holocene land-cover reconstructions for studies on land cover-climate feedbacks. Clim Past 6(4):483–499

Gaillard M-J (2015) LandCover6k: global anthropogenic land-cover change and its role in past climate. Pages Mag 23(1):38–39

Gedge E (1892) A recent exploration, under Captain F. G. Dundas, R. N., up the River Tana to Mount Kenia. Proc R Geogr Soc Monthly Rec Geogr 14(8):513–533

Gifford-Gonzalez D, Hanotte O (2011) Domesticating animals in Africa: implications of genetic and archaeological findings. J World Prehist 24:1–23

Gifford-Gonzalez D, Hanotte O (2013) Domesticating animals in Africa. In: Mitchell P, Lane P (eds) The Oxford handbook of African archaeology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 491–506

Gillman CA (1936) A population map of Tanganyika territory. Geogr Rev 26(3):353–373

Goldewijk KK (2001) Estimating global land use change over the past 300 years: The HYDE database. Global Biogeochem Cy 15(2):417–433

Goldewijk K, Beusen A, van Drecht G, de Vos M (2011) The HYDE 3.1 spatially explicit database of human-induced global land-use change over the past 12,000 years. Global Ecol Biogeogr 20(1):73–86

Grigg D (1965) The logic of regional systems. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 55(3):465–491

Grigg DB (1969) The agricultural regions of the world: review and reflections. Econ Geogr 45(2):95–132

Grigg DB (1974) The agricultural systems of the world: an evolutionary approach. Cambridge Geographical Studies, vol 5. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Guelke L (1976) Frontier settlement in early Dutch South Africa. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 66(1):25–42

Guillon R, Quiquérez A, Petit C et al (2013) Stone lines and heaps on South-Western Niger plateaus as remains of ancient agricultural land. In: Djindjian F, Sandrine (eds) Understanding landscapes, from land discovery to their spatial organization. Archaeopress, Oxford, pp 87–96

Håkansson NT (1994) Grain, cattle, and power: social processes of intensive cultivation and exchange in precolonial Western Kenya. J Anthropol Res 50(3):249–276

Håkansson NT (2004) The human ecology of world systems in East Africa: the impact of the ivory trade. Hum Ecol 32:561–591

Håkansson NT (2008) The decentralized landscape: Regional wealth and the expansion of production in Northern Tanzania before the eve of colonialism. In: Cliggett L, Pool CA (eds) Economies and the transformation of landscape. Society for Economic Anthropology monographs, vol 25. Altamira Press, Lanham, pp 239–266

Håkansson NT (2012) Ivory: Socio-ecological consequences of the East African ivory trade. In: Hornborg A, Clark B, Hermele K (eds) Ecology and power: struggles over land and material resources in the past, present, and future. Taylor & Francis, Hoboken

Håkansson NT, Widgren M (2007) Labour and landscapes: the political economy of landesque capital in nineteenth century Tanganyika. Geogr Ann B 3:233–248

Harris DR (1976) Traditional systems of plant food production and the origins of agriculture in West Africa. In: Harlan JR, De Wet JMJ, Stemler ABLA (eds) Origins of African plant domestication. Mouton, The Hague, pp 311–356

Havnevik K (1993) Tanzania: the limits to development from above. Scandinavian Institute of African Studies (Nordiska Afrikainstitutet) in cooperation with Mkuki na Nyota Publ., Tanzania, Uppsala

Hawthorne W (2003) Planting rice and harvesting slaves: transformations along the Guinea-Bissau coast, 1400–1900. Heinemann, Portsmouth

He FN, Li SC, Zhang XZ (2012) Reconstruction of cropland area and spatial distribution in the mid-Northern Song Dynasty (AD1004–1085). J Geogr Sci 22(2):359–370

Höhn A, Neumann K (2012) Shifting cultivation and the development of a cultural landscape during the Iron Age (0–1500 AD) in the northern Sahel of Burkina Faso, West Africa: insights from archaeological charcoal. Quatern Int 249:72–83

Jackson K (1976) The dimensions of Kamba pre-Colonial history. In: Ogot BA (ed) Kenya before 1900: eight regional studies. East African Publishing House, Nairobi, pp 174–261

Kahlheber S, Höhn A, Neumann K (2013) Plant and land use in southern Cameroon 400 B.C.E.–400 B.C.E. In: Stevens CJ, Nixon S, Murray M-A, Fuller DQ (eds) Archaeology of African plant use. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek

Khattar MO (1995) Les sites Gangara, la fin de la culture de Tichitt et l’origine de Ghana. J Africanistes 65(2):31–41

Khattar MO, Grébénart D, Vernet R (1994) Les parcellaires préhistoriques du Tagant (Mauritanie). Bull Soc Préhist Fr 91(6):457–458

Kjekshus H (1977) Ecology control and economic development in East African history: the case of Tanganyika, 1850–1950. Heinemann, London

Koponen J (1988) People and production in late precolonial Tanzania: history and structures. Monographs of the Finnish Society for Development Studies, 0284–4818, vol 2. Finnish Society for Development Studies, Helsinki

Kottek M, Grieser J, Beck C et al (2006) World map of the Koppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol Z 15(3):259–263

Le Bourdiec F (1974) Hommes et paysages du riz à Madagascar: étude de géographie humaine. s.n., Antananarivo

Le Roy X, Kane M, Marcellin C et al (2005) Pauvreté et accès à l’eau dans la vallée du Sénégal. Paper presented at the international Symposium on Pauvreté hydraulique et crises sociales, Agadir, 12–15 December 2005

Li BB, Jansson U, Ye Y et al (2013) The spatial and temporal change of cropland in the Scandinavian Peninsula during 1875-1999. Reg Environ Change 13(6):1325–1336

Maggs T (1980) The Iron-Age sequence South of the Vaal and Pongola Rivers-some historical implications. J Afr Hist 21(1):1–15

Maggs T (1984) The Iron Age south of the Zambezi. In: Klein RG (ed) Southern African prehistory and paleoenvironments. Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 329–360

Mann CC (2005) 1491: new revelations of the Americas before Columbus, 1st edn. Knopf, New York

Marzouk Y (1989) Societes rurales et techniques hydrauliques en Afrique. Étud rurales 115–116:9–36

McCann J (1995) People of the plow: an agricultural history of Ethiopia, 1800–1990. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

McEvedy C, Jones R (1978) Atlas of world population history. Penguin, London

Miracle MP (1967) Agriculture in the Congo basin: tradition and change in African rural economies. Madison

Monson J (1991) Agricultural transformation in the Inner Kilombero Valley of Tanzania, 1840–1940. University of California, Los Angeles

Morgan WB (1969) Peasant agriculture in tropical Africa. In: Thomas MF, Whittington GW (eds) Environment and land use in Africa. Methuen, London, pp 241–272

Östberg W (2004) The expansion of Marakwet hill-furrow irrigation in Kenya. In: Widgren M, Sutton JEG (eds) Islands of intensive agriculture in Eastern Africa. James Currey, Oxford, pp 19–48

Paul J-L (2003) Anthropologie historique des Hautes Terres de Tanzanie orientale: stratégies de peuplement et reproduction sociale chez les Luguru matrilinéaires. IFRA, Paris; Nairobi, Karthala

Pélissier P (1966) Les paysans du Sénégal: les civilisations agraires du Cayor à la Casamance. Fabrègue, Saint-Yrieix

Petek N, Lane P (2017) Ethnogenesis and surplus food production: communitas and identity building among nineteenth-and early twentieth-century Ilchamus, Lake Baringo, Kenya. World Archaeol:1–21

Pongratz J, Reick C, Raddatz T et al. (2008) A reconstruction of global agricultural areas and land cover for the last millennium. Global Biogeochem Cy 22(3)

Powell JM, Williams TO (1993) An overview of mixed farming systems in sub-Saharan Africa. In: Powell JM, Fernandez-Rivera S, Williams TO, Renard C (eds) Livestock and sustainable nutrient cycling in mixed farming systems of sub-Saharan Africa, vol 2, Technical Papers. International Livestock Centre for Africa, Addis Ababa

Prudencio CY (1993) Ring management of soils and crops in the West-African semiarid tropics:-the case of the Mossi farming system in Burkina-Faso. Agr Ecosyst Environ 47(3):237–264

Ramankutty N, Foley JA (1999) Estimating historical changes in global land cover: Croplands from 1700 to 1992. Global Biogeochem Cy 13(4):997–1027

Reid A (2001) Bananas and the archaeology of Buganda. Antiquity 75(290):811–812

Reinwald B (1997) ‘Though the earth does not lie’: Agricultural transitions in Siin (Senegal) under colonial rule. Paideuma 43:143–169

Ruddiman WF (2003) The anthropogenic greenhouse era began thousands of years ago. Clim Change 61(3):261–293

Russell T, Silva F, Steele J (2014) Modelling the spread of farming in the Bantu-speaking regions of Africa: An archaeology-based phylogeography. Plos One 9(1)

Sautter G (1962) A propos de quelques terroirs d’Afrique Occidentale: Essai comparatif. Études rurales 4:24–86

Schneider HK (1970) The Wahi Wanyaturu: economics in an African society. Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology, vol 48. Wenner-Gren Foundation, New York

Schoenbrun DL (1998) A green place, a good place: agrarian change, gender, and social identity in the Great Lakes region to the 15th century. Heinemann, Portsmouth

Soper R (2002) Nyanga: ancient fields, settlements and agricultural history in Zimbabwe. Memoirs of the British Institute in Eastern Africa, vol 16. The British Institute in Eastern Africa, London

Stamm V (1994) Anbausysteme und Bodenrecht in Burkina Faso. Afr Spectr:247–264

Stanley HM (1872) How I found Livingstone: travels, adventures, and discoveries in Central Africa; including four months’ residence with Dr. Livingstone. Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, London

Stump D (2006) The development and expansion of the field and irrigation systems at Engaruka, Tanzania. Azania 41:69–94

Stump D, Tagseth M (2009) The history of pre-colonial and early colonial agriculture on Mount Kilimanjaro: A review. In: Clack TAR (ed) Culture, history and identity: landscapes of inhabitation in the Mount Kilimanjaro Area, Tanzania. BAR international series, vol 1966. Archaeopress, Oxford, pp 107–124

Sutton JEG (1979) Towards a less orthodox history of Hausaland. J Afr Hist 20(2):179–201

Sutton JEG (1989) Towards a history of cultivating the fields. Azania 24:99–113

Sutton JEG (ed) (1996) The growth of farming communities in Africa from the Equator southwards. Azania 29(30). British Institute in Eastern Africa, Nairobi

Sutton JEG (1993) Becoming Maasailand. In: Spear T, Waller R (eds) Being Maasai: ethnicity and identity in East Africa. James Currey, Oxford, pp 38–68

Tadesse M, Alemu B, Bekele G et al (2006) Atlas of the Ethiopian rural economy. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); Central Statistical Agency; Ethiopian Development Research Institute

Vansina J (1990) Paths in the rainforests: toward a history of political tradition in equatorial Africa. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

Viguier P (2008) Sur les traces de René Caillié: le Mali de 1828 revisité. Éditions Quae, Versailles

von Oppen Av (1993) Terms of trade and terms of trust: the history and context of pre-colonial market production around the Upper Zambezi and Kasai. Studien zur afrikanischen Geschichte, vol 6. Lit, Münster

Watson EE (2009) Living terraces in Ethiopia: Konso landscape, culture and development. Eastern Africa series. James Currey, Oxford

Watts M (1983) Silent violence: food, famine, and peasantry in northern Nigeria. University of California Press, Berkeley

Westerberg L-O, Holmgren K, Börjeson L et al (2010) The development of the ancient irrigation system at Engaruka, northern Tanzania: physical and societal factors. Geogr J 176:304–318

Whitmore TM, Turner BL (2001) Cultivated landscapes of middle America on the eve of conquest. Oxford geographical and environmental studies. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Whittlesey D (1936) Major agricultural regions of the earth. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 26(4):199–240

Widgren M (2010a) Mapping Global Agricultural History. In: Kinda A, Komeie T, Mnamide S, Mizoguchi T, Uesugi K (eds) Proceedings of the 14th international conference of historical geographers, Kyoto 2009. Kyoto University Press, Kyoto, pp 211–212

Widgren M (2010b) Besieged palaeonegritics or innovative farmers: historical political ecology of intensive and terraced agriculture in West Africa and Sudan. Afr Stud 69(2):323–343

Widgren M (2012) Slaves: Inequality and sustainable agriculture in pre-colonial West Africa. In: Hornborg A, Clark B, Hermele K (eds) Ecology and power: struggles over land and material resources in the past, present, and future. Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon, pp 97–107

Widgren M (2017) Agricultural intensification in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1500–1800. In: Austin G (ed) Economic development and environmental history in the Anthropocene: perspectives on Asia and Africa. Bloomsbury Academic, London, pp 51–67

Widgren M, Maggs T, Plikk A et al (2016) Precolonial agricultural terracing in Bokoni, South Africa: typology and an exploratory excavation. J Afr Archaeol 14(1)

Wolmer W, Scoones I (2000) The science of ‘civilized’ agriculture: the mixed farming discourse in Zimbabwe 99(397):575–600

Yasuoka H (2013) Dense wild yam patches established by hunter-gatherer camps: beyond the wild yam question; toward the historical ecology of rainforests. Hum Ecol 41(3):465–475

Ylvisaker M (1979) Lamu in the nineteenth century: land, trade, and politics. African research studies, vol 13. African Center, Boston University, Boston

Acknowledgements

A map like this is by nature always in progress. This version benefitted greatly from important critical remarks and suggestions from the participants of 8th International Workshop for African Archaeobotany in Modena 2015 and of the PAGES LandCover6k workshop in Utrecht 2016, two anonymous reviewers, from the editors of this volume and many other colleagues. But as a work in progress much more can be done to improve it. The GIS-file can be critically scrutinized by downloading it from https://doi.org/10.17045/sthlmuni.5173477. Please quote this chapter if the GIS file is used in further work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Widgren, M. (2018). Mapping Global Agricultural History: A Map and Gazetteer for Sub-Saharan Africa, c. 1800 AD. In: Mercuri, A., D'Andrea, A., Fornaciari, R., Höhn, A. (eds) Plants and People in the African Past. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89839-1_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89839-1_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-89838-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-89839-1

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)