Abstract

This paper provides an ecofeminist response to Christine Overall’s moral argument in her 2012 volume, Why Have Children?, which recommends that individuals in the global West ought to reproduce at a replacement rate in light of environmental concerns. Overall’s recommendation does not adequately account for the sociopolitical context in which human beings have children. The ecofeminist response is one which recommends increased access to education, and sexual education in particular, of low-income women and women of color. Increased educational opportunities for these key groups will lower birth rates by allowing women to choose how and when to have children, as well as by improving access to financial and career incentives for delaying childbirth.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

In her book entitled Why Have Children?, Christine Overall addresses ethical implications of procreation for the most part from the perspective of Western heterosexual couples who are considering whether or not to have biological children. She argues that couples ought to justify their reasons for reproducing rather than having to defend their choice not to reproduce. In subsequent chapters, Overall discusses moral considerations surrounding the choice to procreate, drawing from diverse arguments that populate the literature on reproduction. In chapter 9 of her book, Overall considers arguments against reproduction that stem from the overtaxing of Earth’s resources and issues of overpopulation. Ultimately, she concludes that we have a moral obligation—although not a legal or social one—to procreate at a replacement rate, which is to say that every person is entitled to one biologically related child. Overall’s argument in favor of replacement-rate reproduction misses the point in that it addresses a widespread socio-environmental phenomenon with a highly individualized moral recommendation to limit reproduction based on personal choice. The environmental issues surrounding reproduction in the global West would be more effectively addressed using an ecofeminist approach emphasizing social and educational reform than by personal moral reflection.

In beginning my argument, it will be helpful to first provide a brief overview of the ecofeminist framework within which I am working. Karen Warren characterizes ecofeminism as drawing on “feminism, ecology and environmentalism, and philosophy in its analyses of human systems of unjustified domination” (Warren 2000: 43). She goes on to elaborate that “there are important interconnections among the unjustified dominations of women, other human Others, and nonhuman nature” (Warren 2000: 43). Understanding these intersections is vital in determining solutions to these issues of domination, she argues, as to address either issues of ecological domination or of gendered domination simply is to address the other.

Ecofeminist activism has inherently to do with advancing policies and practices which pertain to a particular intersection between issues of gender equality and environmental care. To say that the two issues are importantly related is not to state outright that any solution to one of these problems will automatically be a solution to the other. Rather, it recognizes an important relationship between women and the environment and women as an environment. Further, the ecofeminist movement recognizes that this relationship means, not that all solutions to one are solutions to both but that the best policies and practices used to address one issue will inherently improve the other. According to Warren, “ecofeminist philosophy is not, is not intended to be, and should not be limited to ‘describing’ reality or reporting ‘facts’; it involves advancing positions, advocating strategies, and recommending solutions. This prescriptive aspect of ecofeminist philosophy is central to doing philosophy” (Warren 2000: 43). It is in this prescriptive element I hope to advance in my project; I want to recommend and justify social and political ways to simultaneously improve the conditions of women and of the environment. In this case, my aim is to advance and justify policy recommendations that benefit women, particularly low-income women and women of color in the global West, by improving access to education and economic opportunity. Greater access to education and economic opportunity will then simultaneously benefit the state of the environment by reducing the number of overall births to women in the global West.

In chapter 9 of her book, Overpopulation and Extinction , Overall establishes the environmental issues that inform reproductive choices for couples in the West. She acknowledges that overpopulation, while problematic, is not necessarily the main problem at work in developed nations (Overall 2012: 178). Rather, overpopulation is of greater concern in developing areas where women are less likely to have access to birth control and education. However, Overall cites Corinne Maier in asserting that overconsumption on the part of developed nations poses an extreme threat to the environment. Maier writes, “It’s not that there are too many people on the planet—there are just too many rich people” (Overall 2012: 178). Overall elaborates that “in general, children in developing countries generate less net cost to the environment that children in developed countries… [P]lanetary capacity is not merely a matter of how many human beings there are, but how those human beings live their lives” (Overall 2012: 179). People in the West consume a great deal more than in other areas; Overall cites Scott Wisor when she writes that, for example, “one U.S. citizen consumes as much energy is 900 Nepalis” (Overall 2012: 186). Overall therefore concludes that “Because of the dangers of planetary overload, the responsibility to limit the number of one’s offspring falls on the people living in the developed world” (Overall 2012: 179).

While Overall acknowledges that we in the West have a responsibility to limit our number of offspring, this responsibility is entirely an ethical one; she writes that “we in the developed world have a moral responsibility to limit our numbers, given the current threats to planetary capacity posed by overpopulation” (Overall 2012: 179). The moral nature of this responsibility is consistent with the conclusion that she establishes in previous chapters, which she recapitulates in the introduction to chapter 9; she writes that “Human beings have a right not to reproduce” but that they also have “a right to reproduce in the negative or liberty sense” (Overall 2012: 174). Thus, because human beings have the right to refuse to procreate, it is logically consistent that they may also have some additional moral obligation not to. However, because we also have a negative right to procreate (in other words, no one can interfere legally or physically with our ability to have children), there can be no positive provision forbidding couples or individuals from reproducing. Overall holds up China’s One Child Policy as an example of such a positive legal provision against procreation and gives some additional reasons why it would be ineffective; it has resulted in a skewed ratio of males to females given that female fetuses are often aborted and female infants (more often than male infants) are exposed or abandoned, an imbalance between the elderly and youth who are available to take jobs caring for them and a state of affairs in which there is only one child to care for two aging parents. A legal provision limiting procreation in the West is, therefore, from a rights perspective infeasible and from a consequences perspective undesirable. Consequently, Overall turns to a model of personal moral responsibility in order to curb reproduction in developed nations.

Overall writes that limiting our reproduction is a responsibility of the developed world for a number of reasons. First, “most of us living in the global West are on average well educated. As a result, we know (or should know) about the dangers of overpopulation,” but further “we collectively are also sufficiently informed to know how to curb our numbers” (Overall 2012: 179). Second, “we in the West consume far out of proportion to our numbers” (Overall 2012: 179). I would also add to this second point that the consequences of that consumption is largely outsourced; because we no longer produce the bulk of what we consume, pollutants and other consequences of large-scale production fall on nations which are not so developed. Third, “we in the West have the ability—the research, resources, and technologies—to limit the number of children we have” (Overall 2012: 179). This is to say that we in the West have the most access to the best forms of birth control currently available, and so we are more able to effectively and safely control our reproduction. Given all of these advantages and the many consequences of our proliferation, it does certainly seem to fall to us in the West to take steps to limiting our population. Overall writes that “Entire societies must take responsibility for curbing population growth; decisions must be made and policies enacted on a national level” (Overall 2012: 180). However, she remains steadfast in her assertion that the decision not to reproduce is a personal one; she continues, “Nonetheless, population will not stabilize, let alone decline, without active decisions being made by individuals. Societies do not have fewer babies; individuals do” (Overall 2012: 180).

Overall goes on to develop this personal moral responsibility model for limiting reproduction. She cites Thomas Young in acknowledging that procreation in the global West is fraught with ethical issues; she quotes him in saying that “having even just one child in an affluent household usually produces environmental impacts comparable to what mainstream environmentalists consider to be an…unacceptable level of consumption, resource depletion, and waste” (Overall 2012: 181, citing Young) and that human procreation is therefore “morally wrong in most cases” (Overall 2012: 180).

Consumption, resource depletion, and waste certainly are a significant problem in the global West, and in the United States in particular. According to energy consumption information published by the University of Michigan’s Center for Sustainable Systems in August 2016, the United States comprises approximately 5% of the world’s population and yet consumes at least 18% of the world’s energy (University of Michigan 2016). Further, “Each day, U.S. per capita energy consumption includes 2.5 gallons of oil, 13.7 pounds of coal, and 234 cubic feet of natural gas” (University of Michigan 2016). To compare energy consumption in the United States with the energy use of a developing country, let’s take a look at India. The population of India is approximately 1260 million people, while that of the United States is about 314 million, yet the United States uses over four times as much energy as India does (World Population Balance 2015). In rough equivalency terms, a woman in India would have to have 17 children in order to equal the lifetime consumption of just one American child (World Population Balance 2015). Indeed, on average, one American consumes as much energy as 6 Mexicans, 31 Indians, and 370 Ethiopians (International Business Guide 2016). Given that this energy is still source primarily from fossil fuels, this high level of consumption is also contributing to resource depletion and the rise in global temperature. The average American also uses 159 gallons of water daily, compared with over half of the world’s population that lives on 25 gallons (International Business Guide 2016). In terms of waste, each person in the United States generates about 5.7 pounds of garbage each day, much of that edible food waste (International Business Guide 2016). Ultimately, given the rate and amount of American consumption of energy resources, food, and water, if every country consumed at the same rate as the United States, we would require 4.4 Earths to sustain us (International Business Guide 2016). Given the statistical evidence that Americans dramatically out-consume their counterparts in the developing world, it seems obvious that procreation in the United States—and likely much of the global West—presents grave ethical concerns.

Despite this strong, evidence-based claim, however, Overall disagrees “with Young’s idea that westerners…should give up procreation altogether” (Overall 2012: 181). She writes that “an obligation not to have any children at all would be a huge sacrifice, one that is too much to expect of anyone who wants to have children” (Overall 2012: 181). Here, Overall already sets a precedent that individual preference trumps the pressing environmental concerns surrounding reproduction in a context of wealth and privilege. Instead, she proposes “a one-child-per-person morality,” whereby every person is entitled to produce one genetically related child (Overall 2012: 183). Every single person is entitled to a single child, and couples are entitled to two between them. She argues that this moral recommendation will be easier to follow than a one-child-per-couple policy, that it implicitly endorses the value of every adult as worthy of being reproduced, and that it will “eventually result in population decline, given that some people will have no children and some couples will choose to have only one” (Overall 2012: 183). It bears repeating, perhaps, that this moral recommendation cannot ever be, as per Overall’s own view, a legal policy in any nation given that we have a negative right to reproduce. Rather, the choice to adhere to this recommendation lies purely with the individual or couple considering whether or not they will have a child or children.

There seem, even prior to a larger ethical critique of this view, to be several practical issues with a one-child-per-person morality. The first of these concerns is that it fails to account for instances of accidental pregnancy, which can be prevalent; in the United States in 2011, approximately 45% or 2.8 million of the 6.1 pregnancies in the United States were unintended (which is to say either mistimed or unwanted) (Guttmacher Institute 2016). My second practical concern is that many couples may choose to have more than one child per person despite their personal moral feeling about the ethical status of procreation in a social context of high consumption, energy use, and waste.

Given the urgency and severity of the environmental stakes of reproduction in the Western world, I cannot imagine that Overall’s one-child-per-person morality could be sufficient to curb the number of offspring we in the West produce in time to halt or reverse the damage we have already done to our Earth and to the other parts of the world that bear the brunt of that damage. Although she asserts that her moral recommendation can apply to everyone, even those whose religious beliefs might preclude the use of birth control or the limiting of offspring (Overall 2012: 188), Overall’s own claim that an individual’s or a couple’s desire to procreate trumps the concern that procreation might nearly always be immoral in the West sets a precedent that having children is more important to individuals than adhering to moral recommendations. Simply put, if a person wants a third child—whether because they really wanted a girl or just because they want a big family—they will have that child in spite of any number of moral considerations.

Fortunately, Overall does provide a way into answering this problem of couples having children despite their own moral concerns. This answer is a social one, despite her explicitly individualistic framework for reproductive choice. She writes in her introduction that “Because the context of procreation is political”—and I would add social and economic, as well—“reproductive decision making cannot realistically be discussed outside of a feminist framework” (Overall 2012: 9). I will argue, therefore, that limiting reproduction in the global West is a matter of implementing widespread social change and applying policies that empower women to make informed choices about childbearing and rearing.

It is perhaps worth noting here that Overall’s reflection is explicitly moral in nature, while my proposed turn to education and policy represents a potential social and political solution to the issue of overpopulation in the West. This turn is significant in part because of the ambiguous nature of the moral claim that we ought to bear environmental concerns in mind when deciding whether or not to have children; should the environment be preserved because it is intrinsically good? Do we have obligations to future generations of human beings such that we ought to attempt to conserve resources and maintain a suitable ecosystemic balance for their sake? These questions are ones which have not been conclusively answered even in many volumes.

The sociopolitical approach, drawing from ecofeminist thought, identifies problems that exist presently and which have an impact both on women and on our environment. The problem I identify in this paper is that women, particularly low-income women and women of color, do not necessarily have the educational or financial resources or motivations to forego childbearing, resulting in a higher overall birth rate in the global West, the region most likely to overconsume. The ecofeminist approach attempts to suggest or deliver solutions to those problems, solutions that simultaneously benefit both women and the environment. This is an important feature of the ecofeminist approach; we ought not address feminist issues for the sake of the environment, nor ought we address environmental issues for the sake of women. Rather, oppression of one is inherently oppression of the other, and the effects of this relationship are already evident globally. Diane-Michelle Prindeville provides the example of Navajo and Pueblo communities whose lands in New Mexico have been co-opted by mining companies attempting to meet increasing demands for mineral resources (Prindeville 2004: 94). These mining operations cause tremendous environmental destruction, and the toxic runoff from these facilities is not only causing widespread health concerns like asthma, but it is now evident in the breast milk of women living in those Navajo and Pueblo communities (Prindeville 2004: 94). Women’s bodies, and specifically those women living in poverty who are most at risk of environmental degradation-related health concerns, have become the very site of environmental oppression. The best long-term solution is fewer human beings whose demands for resources must increasingly be met with environmentally toxic practices.

We see, therefore, that in addressing the disproportionate effects of environmental degradation on women in low-income communities and communities of color, our solution must be one that improves the ability of these same women to choose when to have children and how many they want to have.

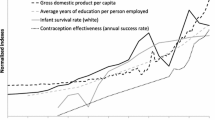

There are many factors that determine how many children an individual woman or a woman in a committed couple will have in her lifetime. While access to birth control, Plan B, women’s health and family planning resources, and abortion services are instrumental in giving women more control over their reproductive choices, the most significant factors in determining how many children a woman will have are education and economic opportunity. According to the Population Reference Bureau’s 2012 Fact Sheet on United States fertility:

longer-term fertility trends may depend on future trends in women’s employment and earnings relative to men.8 Women outnumber men in college and make up a growing share of the labor force. The [2008] recession hit male-dominated jobs the hardest, contributing to a growing share of women who now outearn their husbands.9 As more women become primary breadwinners, fertility decisions are more likely to hinge on women’s earnings than they did in previous decades. A growing reliance on women’s employment and earnings could further dampen U.S. fertility rates in the coming decades. (Mather 2012)

Whether or not a woman chooses to take advantage of birth control or abortive options depend first on whether or not she is sufficiently educated to know how to take advantage of those options, second whether she can afford them, and third whether she has the financial motivation to delay or forego childbirth and/or childrearing altogether. These factors tend to have racial and socioeconomic implications. For example, 2012 data suggests that fertility rates among Latinas and black women have dropped in recent years to rates more similar to those of white women, which correlates with higher rates of enrollment in college (Mather 2012). The Population Reference Bureau reports that “Among 18–24-year-olds, more women than men are enrolled in college in every racial and ethnic group” (Mather 2012). College enrollment, in turn, is correlated with higher future earning power and a greater presence in the job market.

Conversely, lower levels of education tend to correlate with higher numbers of children and higher rates of unplanned pregnancy in particular. According to the Brookings Institute, “unintended birth rates are nearly four times higher for high school drop outs than for college graduates” (Sawhill and Karpilow 2013). Further, rates of unintended pregnancy drop steadily as the level of education increases. (See Unintended Birth Rates by Educational Attainment, below (Sawhill and Karpilow 2013)).

The Brookings Institute found that while increased and low-cost access to birth control is an effective short-term measure for preventing unintended pregnancy, the more effective solution would be to ensure the education of disadvantaged women. According to their findings:

In the short run, reducing unintended pregnancy will require significant changes in contraceptive behavior. For instance, the Choice Project—a program that provided no-cost contraception to nearly 10,000 women in the St. Louis region (many of whom were unmarried and from low socio-economic backgrounds)—shows that getting women onto highly effective, low-maintenance forms of contraception (e.g., IUDs or implants) can massively reduce the incidence of unintended pregnancy. In the longer term, however, radical reductions in unintended childbearing will require improving the educational attainment and economic prospects of the most disadvantaged. (Sawhill and Karpilow 2013)

Statistics furnished by the Guttmacher Institute support this conclusion: according to their findings, unintended pregnancy rates are highest among poor- and low-income women and minority women (Guttmacher Institute 2016). Indeed, “the rate of unintended pregnancy among poor women (those with incomes below the federal poverty level) as 112 per 1,000 in 2011, more than five times the rate among women with incomes of at least 200% of the federal poverty level” (Guttmacher Institute 2016).

There is also a stark divide in unintended pregnancy rates along racial lines: “At 79 per 1,000, the unintended pregnancy rate for black women in 2011 was more than double that of non-Hispanic white women (33 per 1,000)” (Guttmacher Institute 2016).

It is worth noting here that, even in the case of our nation’s poor, poor Americans tend to out-consume the poor in other countries. Peter Singer writes in The Life You Can Save that:

In wealthy societies, most poverty is relative…In the United States, 97 percent of those classified by the Census Bureau as poor own a color TV. Three quarters of them own a car. Three quarters of them have air-conditioning. Three quarters of them have a VCR or DVD player. All have access to healthcare. (Singer 2010, 8)

Thus, even the poor in the United States consume, in a relative sense, a substantial amount of resources. Even if higher birth rates are concentrated among the United States’ poor, those births still represent a greater level of consumption than high birth rates in developing nations. This level of consumption has to do not only with a culture of consumption but also with hidden resource costs associated with owning or eating certain things, such as the water usage of beef versus soy or wheat. It is therefore still in the best interest of the environment to curb fertility rates across socioeconomic lines in the United States, particularly in terms of preventing unintended pregnancy.

Rates of pregnancy, then, are not simply a matter of individual choice. Rather, we can identify significant socioeconomic, racial, and educational factors that contribute to birth rates in developed nations, and in the United States in particular. The nature of these factors belies Overall’s claim that curbing fertility in the global West is a matter of personal choice. While personal reflection is certainly warranted when deciding whether or not to have a child, Overall’s personal moral reflection method seems to miss the point that pregnancies, and especially the factors that contribute to pregnancy, are not always chosen.

Given the facts of pregnancy in the United States, a country in which women of color have a greater chance of living at or below the poverty line and those who are poor and uneducated tend to have higher rates both of fertility and unintended pregnancy, the way forward seems clear. The very best way we can curb fertility and therefore overconsumption in the United States is to improve access to and quality of education, particularly for lower-income women and women of color. I have already demonstrated that education in general tends to benefit women and women of color in particular by improving their opportunities for employment and reducing the number of unplanned pregnancies that they experience. Keeping women in school, preferably through the university level, is the most effective way to achieve a substantial reduction in the national rate of fertility. A higher level of educational attainment, in turn, translates into greater earning potential and more job opportunities, which tend to correlate with childbearing later in life. Access to quality education, therefore, serves the dual purpose of empowering women and curbing our national ecological footprint. Clearly, there is a great deal more to be said about education attainment and fertility, but it is a larger discussion than I currently have room to address.

Now that we have established the benefits of education in general for reducing fertility rates, the next natural step is to discuss sexual education in particular. According to a Planned Parenthood memo on reducing teenage pregnancy in the United States:

Only 11 states plus the District of Columbia require sex education that includes information about contraception. Six other states require that if sex education is provided, it must include information about contraception (Frost et al. 2013). Recent studies show that more teens receive formal sex education on “how to say no to sex” (87 percent of teen women and 81 percent of teen men) than on contraception methods (70 percent of teen women and 62 percent of teen men).

Abstinence-only sexual education does not address contraception or consequences of sexual intercourse, which include sexually transmitted infection and, most importantly for our discussion, unintended pregnancy. This gap in sexual education is particularly troubling given the young age of first sexual activity. According to the Planned Parenthood memo, over 60% of teens have had sex by grade 12 (Planned Parenthood 2013). Further, many young people are unaware of the kinds of contraceptives that are available: “Half of teens have not heard of emergency contraception and do not know that there is something a woman can do to prevent pregnancy after unprotected sex” (Planned Parenthood 2013). Sexual education in the United States that is medically accurate and comprehensive, starts early, and continues through grade 12 is proven to be more effective at postponing first intercourse and preventing unintended teen pregnancy through higher rates of contraceptive use (Planned Parenthood 2013). Says Planned Parenthood:

The most effective programs in the U.S. combine medically accurate information on a variety of sexuality-related issues, including abstinence, contraception, safer sex, and the risks of unprotected intercourse and how to avoid them, as well as the development of communication, negotiation, and refusal skills. Teens who have sex education are half as likely to experience a pregnancy as those who attend abstinence-only programs. (Kohler et al. 2008)

In other developed nations, comprehensive and medically accurate sexual education has resulted in teen birth rates that are between two and four times lower than those in the United States currently (Planned Parenthood 2013).

Sexual education early in life and through high school graduation, in turn, can have a tremendous impact later in life. Knowledge about contraception is a benefit to people of all ages, and a woman who is informed about the types of contraception at her disposal will have an easier time accessing and using whatever method she chooses. Furthermore, the “communication, negotiation, and refusal skills” (Planned Parenthood 2013), discussed by Planned Parenthood as a vital part of sexual education, no doubt prove useful later in life; we discussed earlier the ways in which a woman’s bargaining power in a marriage due to career or financial success has contributed to lower birth rates in the United States. Along those same lines, learning how to negotiate in a specifically sexual or procreative context may help women to gain more control over their fertility in relationships or marriages. The benefits of a comprehensive sexual education are far reaching and help to limit fertility both in a woman’s teenage years and beyond.

Education, and sexual education in particular, are not the only ways to limit the environmental footprint of the United States. The abolition of factory farm subsidies, funding for alternative energy research, and widespread advocacy for a vegetarian or vegan diet would all help to reduce the impact of our consumption. However, given the pervasive nature of the culture of overconsumption and the inertia of the policy that governs it, I do believe that the best way to limit our environmental impact is to limit our fertility. Given that there are systemic socioeconomic and political factors which contribute to fertility, as I have demonstrated, limiting our reproduction simply cannot be a matter of personal moral reflection, as Overall advocates. More and more effective education for women, and women of color especially, seems to be our best hope for limiting our environmental impact in the coming generations.

Here, I must address possibly the most significant potential objection to my argument; women of color in the United States ought understandably to be skeptical of any attempt, policy-based or otherwise, to curb their fertility. As Dorothy Roberts discusses in Killing the Black Body, this country has a terrible history of forced sterilization, and the imposition of other racists measures to ensure that women of color do not reproduce. Policy itself has been used to “keep Black women from having children” (Roberts 1997: 5). There can be no defense for those measures, and it is for this reason that, in my own recommendations, I focus on education of women rather than medical intervention as a way of reducing the national birth rate. Education, as opposed to medical intervention, expands a woman’s options rather than diminishing them and, as I have demonstrated, also tends to lead to motivations to postpone childbearing. Roberts writes that the “traditional understanding of reproductive freedom” in the United States “has had to accommodate practices that blatantly deny Black women control over critical decisions about their bodies” (Roberts 1997: 6). It is my belief, however, that policy focusing on the education and sexual education of all women can improve a woman’s ability to choose. In keeping with the ecofeminist approach, I believe that this focus on educational policy will do the dual work of improving the lives of women by offering them access to a greater array of educational and financial options and improve the state of our environment by ultimately lowering the national birth rate in highest-consuming country in the world.

Overall’s argument that “societies do not have fewer babies; individuals do” sounds to me a little too much like the argument that “guns don’t kill; people do.” All this argument does is place the burden of controlling a massive social phenomenon on individuals who, because they are fallible and because they have understandable desires, often make immoral choices. Overall herself writes that “Individuals making choices about procreation should not and cannot be regarded as acting in a social void, independent of other people and relationships or outside of the broader culture in which they live” (Overall 2012: 13). The broader culture in which we live is one that values luxury and consumption. Therefore, our propensity in the West to consume much more than we need and to perpetuate that behavior in raising our children represents a pressing social issue. The solution, therefore, cannot be an individual one. If we are to effectively address the issue of overconsumption, overpopulation, and overtaxation of our resources, there will need to be a widespread social push to educate citizens of the global West not only about our reproductive decisions but also our consumptive behaviors more generally.

References

Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan. U.S. energy system factsheet. Pub No CSS03-11. 1; 2016.

Frost JJ, Frohwirth L, Zolna MR, Guttmacher Institute, et al. Contraceptive needs and services. 2013 Update. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/pubs/win/contraceptive-needs-2013.pdf.

Guttmacher Institute. September 2016 fact sheet. Sept 2016. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/unintended-pregnancy-united-states. Accessed 11 Dec 2016.

Guttmacher Institute, Nash, et al. Policy trends in the states: 2016. Guttmacher Institute; 2016. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2017/01/policy-trends-states-2016.

International Business Guide. Hungry planet. http://www.internationalbusinessguide.org/hungry-planet/. Accessed 11 Dec 2016.

Kohler, et al. Abstinence-only and comprehensive sex education and the initiation of sexual activity and teen pregnancy. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(4):344–51.

Mather M. Fact sheet: the decline in US fertility. Population Reference Bureau. 2012. http://www.prb.org/publications/datasheets/2012/world-population-data-sheet/fact-sheet-us-population.aspx. Accessed 11 Dec 2016.

Overall C. Why have children? The ethical debate (basic bioethics). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2012.

Planned Parenthood. Reducing teenage pregnancy. July, 2013. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=18&ved=0ahUKEwjyvMSQuOrQAhXqqFQKHQVmAjo4ChAWCG8wBw&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.plannedparenthood.org%2Ffiles%2F6813%2F9611%2F7632%2FReducing_Teen_Pregnancy.pdf&usg=AFQjCNG1qR. Accessed 11 Dec 2016.

Prindeville D-M. The role of gender, race/ethnicity, and class in activists’ perceptions of environmental justice. In: Stein R, editor. New perspectives on environmental justice: gender, sexuality, and activism. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 2004.

Roberts D. Killing the black body. New York: Pantheon Books; 1997.

Sawhill I, Karpilow Q. Reducing unplanned pregnancy. Brookings Institute. Nov 1, 2013. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/social-mobility-memos/2013/11/01/reducing-unplanned-pregnancy/. Accessed 10 Dec 2016.

Singer P. The life you can save: how to do your part to end world poverty. Reprint ed. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks; 2010.

Warren KJ. Ecofeminist philosophy: a western perspective on what it is and why it matters. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2000.

World Population Balance. Population and energy consumption. 2015. http://www.worldpopulationbalance.org/population_energy. Accessed 11 Dec 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this paper

Cite this paper

Friedman, P. (2018). Social Responses to the Environmental Impact of Reproduction in the Global West: A Critique of Christine Overall’s “Overpopulation and Extinction”. In: Campo-Engelstein, L., Burcher, P. (eds) Reproductive Ethics II. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89429-4_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89429-4_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-89428-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-89429-4

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)