Abstract

Children and their families/guardians admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) experience barriers in communication, exposures to environmental stressors, and challenges in their continuity of care. The admission profiles and psychosocial issues of a pediatric oncology population admitted to a high-volume pediatric tertiary care facility were explored from 2012 to 2015 (N = 187), as a series of independent admission events. The results indicate that the mean age of patients at admission was 9 years old, predominantly male, Caucasian, and admitted with a neurological, hematological, or bone/tissue cancer diagnosis. Patients’ mean length of stay (LOS) varied according to cancer diagnosis. A wide range of cancers was represented, with half of the admissions primarily due to their cancer. Clinical implications include the need to optimize relational continuity and patient/family involvement utilizing cooperative communication. Future research could include investigation of satisfaction scores of families, in relation to PICU LOS as a likely risk factor for adverse psychosocial issues for the family.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The prognosis for children with a cancer diagnosis has improved steadily over the last decades, with 5-year survival rates increasing from ~40% in the 1970s, and doubling to ~80% in the 2000s (Kaatsch, 2010; Steliarova-Foucher et al., 2004). In spite of the many different types of cancers that are diagnosed in children of different ages, their increased survival rates are likely due, in part, to advancements in cancer screening and prevention, treatment options, and life-prolonging support systems (e.g., extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO ]). However, depending on the patient’s age at diagnosis, the type of cancer, and the course of treatment, medical outcomes continue to vary greatly (Dursun et al., 2009).

This chapter describes the pediatric oncology patients of a high-volume tertiary care facility and includes a discussion of psychosocial concerns, environmental stressors, and communication practices related to pediatric cancer patients in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) ). Although concepts are presented within the context of a specific institution, we believe they may be relevant for health-care and oncology providers in any PICU setting. From this chapter the reader will be able to (a) describe the demographics of pediatric cancer patients as admitted to a freestanding, high-volume tertiary care children’s hospital in an urban setting, (b) describe two forms of communication that take place in a PICU, (c) identify some key environmental stressors and themes of involuntary exposure to trauma leading to distress, and (d) critique the psychosocial implications of these factors for the patient and the family, including peri-traumatic dissociation.

A pediatric cancer population is heterogeneous in nature and challenging to treat given the rapidly developing biology of the child and changing psychosocial needs of the family (Wiener, Hersh, & Alderfer, 2011) (for the purposes of this chapter, the term “family” includes designated caregivers). In addition to the immediate challenges surrounding a hospitalization, communication issues between the family and the clinical care team can quickly arise. Physical and physiological stressors of the illness are compounded with parents/guardians who are left to navigate unfamiliar and intimidating hospital settings. In certain instances, transition from a pediatric oncology unit to a PICU may be necessary and unexpected, potentially compounding the stress (Demaret, Pettersen, Hubert, Teira, & Emeriaud, 2012).

Although the topic of pediatric oncology has been explored extensively in medical terms (Fisher & Rheingold, 2011), there are few prospective studies regarding the PICU oncology experience and the specific challenges that result from working with this vulnerable population, which this chapter will not address specifically (Howell, Kutko, & Greenwald, 2011). Effectively managing the PICU course of oncology patients includes pain management, child-life services, and consultations with other sub-disciplines. In particular, transitions in care from a pediatric oncology unit to a PICU need to include wide-ranging clinical decisions and the consideration of environmental stressors (e.g., alarms and noises, such as crying and conversations, light exposure, air quality) and restrictions on family members in a more tightly regulated hospital environment.

As provisions of care evolve, hospitals are increasingly attentive to these environmental factors and the milieu in which care is provided. Concerns about patient satisfaction, psychological distress, coping skills, and quality of life are receiving increased attention and being integrated into the daily care of patients. The burdens of patient and family stress in both pediatric oncology units and PICUs can be alleviated by the involvement of the entire clinical care team , which is often large (>10 individuals) and can include oncologists, nurses, nurse practitioners, intensive care specialists, dietitians, respiratory therapists, social workers, chaplains, pain and palliative care specialists, other medical specialists, child-life specialists, and clinical ethicists.

Overview: Pediatric Cancer Patients

To begin, it is important to note that the definition of the term “pediatric cancer patient” includes not only the child involved, but family members as caregivers and legal guardians of that child. Consent for children’s care is provided by the parents/guardians until the age of “assent” in children, which is approximately 7–11 years old. In this age group, children who are deemed of minimal cognitive age to provide consent may also be included in the decision-making process (Dorn, Susman, & Fletcher, 1995). Ultimately, the parent/guardian remains responsible for consent to procedures (including drug regimens) for their child. This is relevant because the family unit can include two or more individuals (i.e. child-patient, and parent/guardian), all of whose opinions need to be considered.

Pediatric cancers are generally defined as those affecting children up to the age of 18. However, in some instances, patients past the age of 18 retain their relationship with their pediatric oncologist and may return to their pediatric hospital for further care and long-term follow-up. Patients may continue to utilize the treatment protocols related to their pediatric cancers up to the age of 26, on a case-by-case basis (Freyer & Brugieres, 2008). They may require medical attention for long-term health issues that resulted from their pediatric cancer treatments as now adult survivors (Lipshultz et al., 2014; Oeffinger et al., 2006; Tukenova et al., 2010). This is an area that requires further investigation.

Historically, pediatric oncology patients were cared for within an adult hospital setting according to the procedures and policies of an existing hospital framework; practitioners frequently adapted methods used to treat adults for their pediatric patients (DeVita & Chu, 2008). With the development and expansion of specialized children’s hospitals (such as St. Jude, est. 1962), there has been an evolution in the way cancer patients are treated in an inpatient setting , particularly in relation to the application of pediatric-specific quality and safety standards (Neuss et al., 2017). Accomplishing this has required hospital administrators, clinical care providers, and the community to champion the delivery of specialized care for children. The development of freestanding children’s hospitals distinct from the adult setting has further allowed health-care facilities to customize and tailor their approach to the medical and psychosocial needs of all children, including the youngest cancer patients (Fisher et al., 2014).

This customized children’s hospital environment can prove to be especially important for pediatric oncology patients, consisting largely of children with neurological, hematological, head, neck, bone, or tissue cancers. Cancer patients with an acutely worsening condition may require the attention of an intensive care facility, as is required in up to 38% of children (Rosenman, Vik, Hui, & Breitfeld, 2005). Given that the 5-year survival rate is now up to 83% for children’s cancers, a PICU transfer is often required and may be part of the patient treatment trajectory (Rosenman et al., 2005).

Various severity of illness scores are used to measure patient acuity. This score is measured in pediatric patients early in their PICU admission—typically during the first 12 h—before any influence of therapy. One of these acuity measures is the Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM ) score, which correlates the physiologic status with risk of mortality (M. M. Pollack, Ruttimann, & Getson, 1988). This scoring system has evolved over the years; it is now in its third iteration and readily used in most PICUs (Pollack, Patel, & Ruttimann, 1996).

It should be noted that the PRISM score was further developed in 2000 specifically for oncology, which led to the acronym “O” for oncology in “O-PRISM.” This refinement of the scoring system stemmed from some debate regarding the validity of the PRISM score for oncology patients and its later development . It was found to more accurately predict the mortality in ICU bone marrow transplant patients (Schneider et al., 2000) and event-free survival. A high O-PRISM score at the time of admission was predictive of a poorer long-term outcome (Fernandez-Garcia, Gonzalez-Vicent, Mastro-Martinez, Serrano, & Diaz, 2015).

In a recent study reviewing 5 years of patients in a developing country, sepsis and respiratory failure were reported as the most frequent reasons for PICU admissions, requiring urgent intervention with inotropic support, oxygen therapy, and mechanical ventilation (Ali, Sayed, & Mohammed, 2016). In this developing hospital setting, these factors were associated with poor outcomes, especially for those patients with hematological malignancies. In another study, by Dursun et al. (2009) in a Turkish PICU population, risk factors included the number of organ system dysfunctions (n > 2), sepsis, the need for mechanical ventilation, positive inotropic support, and high PRISM III scores (>10) which were negatively associated with survival.

Clinical factors can be exacerbated by the human factor. Pediatric oncology patients who are transferred or sent to a PICU may encounter a situation where the clinical staff are limited in their ability to offer treatment to the patient, especially in the case of a terminal diagnosis. A quote by Theodore Roosevelt conveys the danger inherent in aggressive therapeutic approaches when faced with the bleakest of prognoses: “optimism is a good characteristic but if carried to excess, becomes foolishness” (Peters & Agbeko, 2014) p. 1589). This can be seen in the determination of an oncologist attempting to give a patient one last round of chemotherapy. There are instances when palliative chemotherapy is considered, but can lead to needless prolonging of life and suffering. The question then becomes: when to stop therapeutic interventional treatments and transition to supportive care?

Generally, this can cause a certain degree of nihilism and can be a challenging time for the clinical staff (Christakis & Asch, 1995; Cook et al., 1995; Randolph, Zollo, Wigton, & Yeh, 1997). In one cross-sectional study that surveyed 56 caregivers, 7 patient characteristics were described as the most important factors influencing decisions specifically, family preferences (76%), probability of survival (50%), and functional status (47%) were listed in the top three (Randolph et al., 1997). Evidence from other studies provides insight into the process influencing caregiver decision-making with the use of algorithms (Demaret et al., 2012), which includes family preferences. Oncology patients in a PICU setting will now be discussed.

PICU Oncology Patients of a High-Volume Tertiary Care Facility

To explore the psychosocial and communication issues, and environmental stressors related to cancer patients and PICUs, it is helpful to have an example—in this case, a modern, urban, high-volume pediatric tertiary care facility in Western Michigan.

Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital (HDVCH) is located in Grand Rapids, Michigan. HDVCH operates under the umbrella of Spectrum Health Hospital System, which includes three hospitals in Grand Rapids and nine regional hospitals serving patients across all of Western and Northern Michigan. HDVCH was created at Spectrum Health in 1993 to fill a critical need for a tertiary care referral center devoted to infants, children, and adolescents in the area; in January 2011 HDVCH moved to a newly built, freestanding, 11-story facility (Connors, 2010). HDVCH has a separate PICU on the 8th floor, which handles more than 1500 admissions and 6000 patient days per year. Seventeen board certified intensivists cover the unit, caring for up to 36 critically ill children, with extra patient beds on the 7th floor.

For the purpose of this chapter, and to better understand the patient demographics of PICU oncology patients at HDVCH, we pulled all local patient admissions with an oncological diagnosis (N = 187) from January 2012 to December 2015 from a pediatric critical care registry: Virtual Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Performance Systems (VPS, LLC, Los Angeles, CA). Our assumption was, that the reason for admission and cancer type, might influence the length of stay (LOS) and provide some insight into the psychosocial implications for care.

VPS was established in 2006 to create a cohesive and definitive central capture mechanism for data from all PICUs. It is now an international registry with 135 participating hospitals and >1,000,000 PICU cases, which provides accurate and representative local data, collected daily by site coordinators, and reported through the Clinical Program Performance Reports for Pediatric Critical Care (Wetzel, Sachedeva, & Rice, 2011). Spectrum Health Internal Review Board (IRB) approval was not obtained for this research, as only a minimal, de-identified data set was retrieved; it included age at admission, LOS in the PICU, race/ethnicity, sex, primary and secondary reason(s) for admission, cancer diagnosis, and included perioperative patients.

The resulting patient demographics are described in Table 7.1. The mean age of HDVCH PICU patients with an oncology diagnosis at admission was 114.9 months (~ 9.5 years), with a range from 0.5 to 23 years of age. The demographics of patients admitted exceeded the customary age of 18 because some patients were treated as young adults with pediatric cancers, and their appropriate treatment course had been continued at the original diagnosis and treatment hospital. The dominance of a Caucasian/European ethnicity (75.9%) was in line with the general population demographics of the West Michigan region (“Population and Demographics,” 2016). The neurological patients had the longest overall tendency for LOS as compared to bone/tissue (3.1 days) and hematological (4.1 days) with a mean of 5.7 days, before a patient was sent to another pediatric unit.

Table 7.2 describes the diagnoses for the admitted population of 187 patients. Neurological cancers made up more than half of the total diagnoses, with hematological cancers approximately another quarter of the population, followed by bone and tissue cancers. Neurological cancers made up the majority of admissions as these were surgical in nature (e.g., tumor resection/removal, biopsy retrieval).

Just over half of the HDVCH PICU patients were admitted due to their cancer diagnosis. As Table 7.3 shows, 48.1% presented with an acute symptom due to an underlying cancer diagnosis, such as infections, neurological issues, or cardiovascular/circulatory symptoms.

Psychosocial Issues

For pediatric cancer patients like those at HDVCH, a PICU, by definition, provides a higher level of care and offers “one-on-one” patient-nursing capacity, if needed. This allows the patient to be the sole focus and receive more intensive, focused care. One way in which a PICU differs from a hospital oncology unit is that it enforces greater restrictions on the patient as well as the family. These can include limitations in visiting hours and/or the numbers and types of visitor allowed (e.g., parent/guardian only). There may also be limitations on the physical proximity permitted between the parent/guardian and the child, due to the presence of tubing and/or ventilators. These physical restrictions may interfere with the child’s mobility and/or limit the ability of the parent/guardian to be close to them (e.g., intubated children), resulting in an increase in parental stress levels (Aamir, Mittal, Kaushik, Kashyap, & Kaur, 2014).

Additional stressors to the family can include the introduction of new clinical staff to the family. Patients may have built a relationship with their oncologist, and now their previous physician has ceded care to the intensivist in the PICU. Although an oncology nurse may remain present for continuity of care, this can be a stressful time for the patient and the family as they are introduced to a new environment and new care team. Combined, all of this can generate a “perfect storm” for the parents/guardians, creating what has been termed peri-traumatic dissociation—defined as a state of limited or distorted awareness during and immediately after a stressful event (Bronner et al., 2009; Marmar, Weiss, & Metzler, 1997).

Psychosocial issues in pediatric cancers are complex, dynamic, and multidimensional. The family unit includes not just parents/guardians but the siblings, other family members, the larger family system, and the immediate community. Depending on the age of the child at the time of diagnosis, a range of events can take place, which can include disruptions in social development (Katz, Rubinstein, Hubert, & Blew, 1989), absences from school (Cairns, Klopovich, Hearne, & Lansky, 1982), and disruptions in family dynamics (Brody & Simmons, 2007). Long-term side effects of treatments and medications can persist for some time, with fatigue being reported as the most critical factor in the transition back to school and daily life (Clarke-Steffen, 2001; Hockenberry-Eaton & Hinds, 2000). In addition, a pediatric cancer diagnosis can negatively affect the parent/guardian, resulting in adverse health effects after a PICU admission, with an increased tendency toward suicide, absences from work, and reports of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for both the parent/guardian (Balluffi et al., 2004), and the child (Rees, Gledhill, Garralda, & Nadel, 2004). Lastly, financial burdens can ensue with mounting medical expenses (for a systematic literature review, see Shudy et al. 2006).

Communication

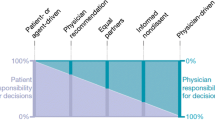

Communication practices related to pediatric cancer patients in the PICU can be broken down into a few different frameworks. There is parent/child communication, which we do not address in this chapter. There is also the communication that happens with the family or “family-centered communication.” And there is cooperative communication, which is communication that takes place between care providers and the family but bypasses any perceived hierarchical structures.

Family-centered communication includes practitioner/family interactions, typically in the form of daily bedside rounds, which take place between 8 a.m. and 11 a.m. Rounds allow the family to meet with the clinical care team and obtain accumulative information regarding their child’s condition and treatment plan for the day(s). Families at this time are encouraged to ask questions and participate in the dialogue. The information is compressed and passed on to the family within a 15–30-min timeframe. This method of communication has developed from theoretical models from a PICU setting—encouraging cross talk, family engagement, and communication with clinical experts—during which the entire clinical team may be present (Baird, Davies, Hinds, Baggott, & Rehm, 2015). This communication comes at a time when the family will feel a sense of disruption, disappointment, and anxiety in the PICU environment, experience a loss of control and yet still desire a continuity of care for their child (Baird, Rehm, Hinds, Baggott, & Davies, 2016; Haggerty et al., 2003).Specifically, Haggerty et al. describes the term “relational continuity”, as trust building over time between patients/families and individual care providers. The importance of communications about patient care cannot be overestimated, as frustration, hyper-vigilance, and mistrust can be avoided and lessened with effective communication practices (Epstein, Miles, Rovnyak, & Baernholdt, 2013; Heller, Solomon, & Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care Investigator, 2005).

Continuity of care promoted by effective communication has been shown to positively affect patient outcomes and lead to fewer nurse-related adverse events (Siow, Wypij, Berry, Hickey, & Curley, 2013). In one investigation of parental satisfaction, a network analysis was employed, which found that the care team’s structure was more important than its size (Gray et al., 2010).

Communication that takes place between couples, clinical staff, and care providers in a given department within a hospital, or between families and care providers, is termed “cooperative communication.” This form of communication may also occur with siblings and the extended family members (the opposite of which is termed confrontational communication). Cooperative communication is a form of communication that is encouraged for families and the clinical care team, also termed parallel communication (Kamihara, Nyborn, Olcese, Nickerson, & Mack, 2015). This can help move a family away from secrecy and collusion and promote positive discourse. In another context, enhancing and encouraging cooperative communication has been shown to be effective for families and nursing home staff, promoting trust and improving family-staff relations at an otherwise stressful time (Pillemer et al., 2003). This results in improved attitudes, the ability to work better together, families reporting less conflict with staff, and staff reporting a decreased likelihood of quitting their jobs, so all in all positive.

Environmental Stressors

When a pediatric cancer patient transfers to a PICU from a pediatric oncology unit, this transition can be sudden, unexpected, and fraught with fear and stress for the family (Khanna, Finlay, Jatana, Gouffe, & Redshaw, 2016). In the most extreme cases, the family may not even be present when the transfer happens; they may be absent due to work (or other). Communication among the clinical staff will also be in transition, as staff from both units must rapidly communicate, understand, and adapt to the complex medical needs of the newly arrived PICU patient. They may have limited time in an acute situation to communicate with family members.

Once a patient is admitted to a PICU, there is a change in the immediate environment for both the patient and the family. If the patient was previously on a pediatric oncology floor, there may have been familiarity with the staff, a sense of routine, and certain privileges or freedoms available to friends and family, depending on the medical condition of the patient. In the PICU, the intensity of care is increased and restricted, as mentioned previously (e.g., tests may need to be administered at designated times instead of at the convenience of the patient or family). The use of strong lighting and alarms may be an irritant, along with not being able to coordinate care around the normal circadian rhythms of the patient. Unit-based rules profoundly affect both the patient and the family (Baird et al., 2015), however, are necessary for this chaotic, unpredictable, noisy environment and with so many different care providers, as described in the introduction (Clarke, 2005).

The work of Khanna et al. (2016) showed that involuntary exposure to observed trauma in the PICU was a source of distress and included a few main themes: (a) seeing and hearing people crying, (b) the deterioration and/or appearance of another patient, and (c) seeing children/parents in distress. Other themes included the absence of privacy and confidentiality, insufficient empathy for children and their families, the need for personal reflection and growth, and staff communication. The involuntary environmental exposures were defined as overhearing family members’ conversations, crying, alarms, witnessing seizures, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or death, all of which did not necessarily involve their own child. Collectively, these exposures were a great source of distress that could potentially be alleviated with short-term supports.

Perhaps the greatest environmental distress for the family occurs when a child is in isolation in a PICU. All visitors, including parents/guardians, must wear a gown, gloves, and/or a mask when indicated to prevent the inadvertent exposure and transmission of an outside infection to the patient. Guidelines for appropriate procedures are defined by the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as described in Mehta et al. (Mehta et al., 2014).

Suggested visitation guidelines at HDVCH have attempted to address some of these issues in an effort to minimize environmental stressors to the patient and staff. These include, but are not limited to, reduced visiting hours for siblings, relatives, and friends, no visitors during shift changes (7 a.m.–8 a.m. and 7 p.m.–8 p.m.), only two people allowed to stay overnight at the child’s bedside, and no more than three people at the patient’s bedside at any one time, based on the child’s condition. In addition, families are encouraged to keep personal belongings in the family space, and hand washing is encouraged for everyone going into and out of the room. In certain instances, when the patient is best served by being kept in a low-stimulation room (e.g., the sedated-mechanically-ventilated child), it is recommended that low volumes, dim lights, and a careful, caring touch are administered.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Studies have shown that up to 38% of pediatric oncology patients will require PICU admission within 3 years of diagnosis, with a mortality rate of 6.8% which is almost three times higher than the general PICU population (2.4%) (Zinter, DuBois, Spicer, Matthay, & Sapru, 2014). Hematological cancer patients have the greatest PICU admission acuity, rates of infection, and mortality compared to those with solid tumors, according to Zinter et al. In our patient population, infection also contributed to PICU admissions. It can be challenging to describe, in advance, the changing and evolving needs of these children. There is a desire to maintain relational continuity (as previously defined by Haggerty et. al. in the Communication section) among the patients, families, and individual care providers, as has been described for parents of children with severe disabilities (Graham, Pemstein, & Curley, 2009) and for those that are technology-dependent (Reeves, Timmons, & Dampier, 2006). Unfortunately, relational continuity is not necessarily an integral part of routine care, as discussed by Baird et al. 2016.

One potential barrier to achieving this relational continuity in a PICU setting may be the working preferences of nurses, who might desire to continue caring for a diverse patient population in the PICU and who also may attempt to minimize emotional entanglement with oncology patients (Baird et al., 2016). In this compelling article, Baird describes the following implications in the continuity of nursing care: “nurses understood the need but faced both contextual and personal challenges to achieving continuity, including fluctuations in staffing needs, training demands, fear of emotional entanglement, and concern for missed learning opportunities (p. 1).”

Utilizing cooperative communication in a fluid, ongoing manner, it is possible to prepare the family ahead of time for the potential that a PICU admission may be necessary and thereby decrease stress for the family. Once patients are approximately 7 years old or older, they may become more involved with this cooperative communication. This is especially important for the adolescent and the young adult populations and further investigation is required into their specific psychosocial needs (Straehla et al., 2017).

We believe research in the area of the pediatric PICU experience has significant clinical implications and the potential to lead to best practices for both the developed and the developing world regarding incidence, survival and care, and further implications for psychosocial interventions (Ali et al., 2016). Evolution of this work will result in better interventions and potentiate coping strategies to negate some of the stressful effects and events surrounding a cancer diagnosis and PICU admission in the youngest and most vulnerable of populations.

References

Aamir, M., Mittal, K., Kaushik, J. S., Kashyap, H., & Kaur, G. (2014). Predictors of stress among parents in pediatric intensive care unit: A prospective observational study. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 81(11), 1167–1170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-014-1415-6

Ali, A. M., Sayed, H. A., & Mohammed, M. M. (2016). The outcome of critically ill pediatric cancer patients admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit in a tertiary university oncology Center in a Developing Country: A 5-year experience. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 38(5), 355–359. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000000523

Baird, J., Davies, B., Hinds, P. S., Baggott, C., & Rehm, R. S. (2015). What impact do hospital and unit-based rules have upon patient and family-centered care in the pediatric intensive care unit? Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 30(1), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2014.10.001

Baird, J., Rehm, R. S., Hinds, P. S., Baggott, C., & Davies, B. (2016). Do you know my child? Continuity of nursing Care in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Nursing Research, 65(2), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000135

Balluffi, A., Kassam-Adams, N., Kazak, A., Tucker, M., Dominguez, T., & Helfaer, M. (2004). Traumatic stress in parents of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 5(6), 547–553. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PCC.0000137354.19807.44

Brody, A. C., & Simmons, L. A. (2007). Family resiliency during childhood cancer: The father’s perspective. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 24(3), 152–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454206298844

Bronner, M. B., Kayser, A. M., Knoester, H., Bos, A. P., Last, B. F., & Grootenhuis, M. A. (2009). A pilot study on peritraumatic dissociation and coping styles as risk factors for posttraumatic stress, anxiety and depression in parents after their child's unexpected admission to a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health, 3(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-3-33

Cairns, N. U., Klopovich, P., Hearne, E., & Lansky, S. B. (1982). School attendance of children with cancer. The Journal of School Health, 52(3), 152–155. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6916955.

Christakis, N. A., & Asch, D. A. (1995). Physician characteristics associated with decisions to withdraw life support. American Journal of Public Health, 85(3), 367–372. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7892921

Clarke, A. (2005). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Clarke-Steffen, L. (2001). Cancer-related fatigue in children. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 18(2 Suppl 1), 1–2. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11321844

Connors, R. Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital. (2010). Inaugural Speech, Opening of Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital [Press release]

Cook, D. J., Guyatt, G. H., Jaeschke, R., Reeve, J., Spanier, A., King, D., … Streiner, D. L. (1995). Determinants in Canadian health care workers of the decision to withdraw life support from the critically ill. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. JAMA, 273(9), 703–708. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7853627

Demaret, P., Pettersen, G., Hubert, P., Teira, P., & Emeriaud, G. (2012). The critically-ill pediatric hemato-oncology patient: Epidemiology, management, and strategy of transfer to the pediatric intensive care unit. Annals of Intensive Care, 2(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/2110-5820-2-14

DeVita, V. T., & Chu, E. (2008). A history of cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Research, 68(21), 8643–8653. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6611

Dorn, L. D., Susman, E. J., & Fletcher, J. C. (1995). Informed consent in children and adolescents: Age, maturation and psychological state. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 16(3), 185–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(94)00063-K

Dursun, O., Hazar, V., Karasu, G. T., Uygun, V., Tosun, O., & Yesilipek, A. (2009). Prognostic factors in pediatric cancer patients admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 31(7), 481–484. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181a330ef

Epstein, E. G., Miles, A., Rovnyak, V., & Baernholdt, M. (2013). Parents’ perceptions of continuity of care in the neonatal intensive care unit: Pilot testing an instrument and implications for the nurse-parent relationship. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 27(2), 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0b013e31828eafbb

Fernandez-Garcia, M., Gonzalez-Vicent, M., Mastro-Martinez, I., Serrano, A., & Diaz, M. A. (2015). Intensive care unit admissions among children after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Incidence, outcome, and prognostic factors. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 37(7), 529–535. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000000401

Fisher, B. T., Harris, T., Torp, K., Seif, A. E., Shah, A., Huang, Y. S., … Aplenc, R. (2014). Establishment of an 11-year cohort of 8733 pediatric patients hospitalized at United States free-standing children’s hospitals with de novo acute lymphoblastic leukemia from health care administrative data. Medical Care, 52(1), e1–e6. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824deff9

Fisher, M. J., & Rheingold, S. R. (2011). Oncologic emergencies. In P. Pizzo & D. Poplack (Eds.), Principles and practice of pediatric oncology (6th ed., pp. 1125–1151). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Freyer, D. R., & Brugieres, L. (2008). Adolescent and young adult oncology: Transition of care. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 50(5 Suppl), 1116–1119. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21455

Graham, R. J., Pemstein, D. M., & Curley, M. A. (2009). Experiencing the pediatric intensive care unit: Perspective from parents of children with severe antecedent disabilities. Critical Care Medicine, 37(6), 2064–2070. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a00578

Gray, J. E., Davis, D. A., Pursley, D. M., Smallcomb, J. E., Geva, A., & Chawla, N. V. (2010). Network analysis of team structure in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics, 125(6), e1460–e1467. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2621

Haggerty, J. L., Reid, R. J., Freeman, G. K., Starfield, B. H., Adair, C. E., & McKendry, R. (2003). Continuity of care: A multidisciplinary review. BMJ, 327(7425), 1219–1221. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219

Heller, K. S., Solomon, M. Z., & Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care Investigator, T. (2005). Continuity of care and caring: What matters to parents of children with life-threatening conditions. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 20(5), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2005.03.005

Hockenberry-Eaton, M., & Hinds, P. S. (2000). Fatigue in children and adolescents with cancer: Evolution of a program of study. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 16(4), 261–272. discussion 272–268. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11109271

Howell, J. D., Kutko, M. C., & Greenwald, B. M. (2011). Oncology patients in the pediatric intensive care unit: it’s time for prospective study. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 12(6), 680–681. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182196cc2

Kaatsch, P. (2010). Epidemiology of childhood cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 36(4), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.02.003

Kamihara, J., Nyborn, J. A., Olcese, M. E., Nickerson, T., & Mack, J. W. (2015). Parental hope for children with advanced cancer. Pediatrics, 135(5), 868–874. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2855

Katz, E., Rubinstein, C. L., Hubert, N. C., & Blew, A. (1989). School and social reintegration of children with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 6(3–4), 123–140.

Khanna, S., Finlay, J. K., Jatana, V., Gouffe, A. M., & Redshaw, S. (2016). The impact of observed trauma on parents in a PICU. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 17(4), e154–e158. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000000665

Lipshultz, S. E., Karnik, R., Sambatakos, P., Franco, V. I., Ross, S. W., & Miller, T. L. (2014). Anthracycline-related cardiotoxicity in childhood cancer survivors. Current Opinion in Cardiology, 29(1), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCO.0000000000000034

Marmar, C. R., Weiss, D. S., & Metzler, T. J. (1997). In J. P. Wilson & T. M. Keane (Eds.), The Peritraumatic dissociative experiences questionnaire. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD: A handbook for practitioners. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Mehta, Y., Gupta, A., Todi, S., Myatra, S., Samaddar, D. P., Patil, V., … Ramasubban, S. (2014). Guidelines for prevention of hospital acquired infections. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 18(3), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-5229.128705

Neuss, M. N., Gilmore, T. R., Belderson, K. M., Billett, A. L., Conti-Kalchik, T., Harvet, B. E., … Polovich, M. (2017). 2016 updated American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards, including standards for pediatric oncology. Oncology Nursing Forum, 44(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1188/17.ONF.31-43

Oeffinger, K. C., Mertens, A. C., Sklar, C. A., Kawashima, T., Hudson, M. M., Meadows, A. T., … Childhood Cancer Survivor, S. (2006). Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine, 355(15), 1572–1582. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa060185

Peters, M. J., & Agbeko, R. S. (2014). Optimism and no longer foolishness? Haematology/oncology and the PICU. Intensive Care Medicine, 40(10), 1589–1591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3478-2

Pillemer, K., Suitor, J. J., Henderson, C. R., Jr., Meador, R., Schultz, L., Robison, J., & Hegeman, C. (2003). A cooperative communication intervention for nursing home staff and family members of residents. Gerontologist, 43(Spec No 2), 96–106. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12711730

Pollack, M. M., Patel, K. M., & Ruttimann, U. E. (1996). PRISM III: An updated pediatric risk of mortality score. Critical Care Medicine, 24(5), 743–752. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8706448

Pollack, M. M., Ruttimann, U. E., & Getson, P. R. (1988). Pediatric risk of mortality (PRISM) score. Critical Care Medicine, 16(11), 1110–1116.

Population and Demographics. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.rightplace.org/data-center/population-and-demographics

Randolph, A. G., Zollo, M. B., Wigton, R. S., & Yeh, T. S. (1997). Factors explaining variability among caregivers in the intent to restrict life-support interventions in a pediatric intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine, 25(3), 435–439. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9118659

Rees, G., Gledhill, J., Garralda, M. E., & Nadel, S. (2004). Psychiatric outcome following paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admission: A cohort study. Intensive Care Medicine, 30(8), 1607–1614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-004-2310-9

Reeves, E., Timmons, S., & Dampier, S. (2006). Parents' experiences of negotiating care for their technology-dependent child. Journal of Child Health Care, 10(3), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493506066483

Rosenman, M. B., Vik, T., Hui, S. L., & Breitfeld, P. P. (2005). Hospital resource utilization in childhood cancer. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 27(6), 295–300. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15956880

Schneider, D. T., Lemburg, P., Sprock, I., Heying, R., Gobel, U., & Nurnberger, W. (2000). Introduction of the oncological pediatric risk of mortality score (O-PRISM) for ICU support following stem cell transplantation in children. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 25(10), 1079–1086. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1702403

Shudy, M., de Almeida, M. L., Ly, S., Landon, C., Groft, S., Jenkins, T. L., & Nicholson, C. E. (2006). Impact of pediatric critical illness and injury on families: A systematic literature review. Pediatrics, 118(Suppl 3), S203–S218. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-0951B

Siow, E., Wypij, D., Berry, P., Hickey, P., & Curley, M. A. (2013). The effect of continuity in nursing care on patient outcomes in the pediatric intensive care unit. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 43(7–8), 394–402. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e31829d61e5

Steliarova-Foucher, E., Stiller, C., Kaatsch, P., Berrino, F., Coebergh, J. W., Lacour, B., & Parkin, M. (2004). Geographical patterns and time trends of cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents in Europe since the 1970s (the ACCISproject): An epidemiological study. Lancet, 364(9451), 2097–2105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17550-8

Straehla, J. P., Barton, K. S., Yi-Frazier, J. P., Wharton, C., Baker, K. S., Bona, K., … Rosenberg, A. R. (2017). The benefits and burdens of cancer: A prospective longitudinal cohort study of adolescents and young adults. Journal of Palliative Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0369

Tukenova, M., Guibout, C., Oberlin, O., Doyon, F., Mousannif, A., Haddy, N., … de Vathaire, F. (2010). Role of cancer treatment in long-term overall and cardiovascular mortality after childhood cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28(8), 1308–1315. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2267

Wetzel, R. C., Sachedeva, R., & Rice, T. B. (2011). Are all ICUs the same? Paediatric Anaesthesia, 21(7), 787–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03595.x

Wiener, L., Hersh, S. P., & Alderfer, M. A. (2011). Psychiatric and psychosocial support for the child and family. In P. Pizzo & D. Poplack (Eds.), Principles and practice of pediatric oncology (6th ed., pp. 1323–1346). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Zinter, M. S., DuBois, S. G., Spicer, A., Matthay, K., & Sapru, A. (2014). Pediatric cancer type predicts infection rate, need for critical care intervention, and mortality in the pediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Care Medicine, 40(10), 1536–1544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3389-2

Acknowledgments

VPS data was provided by Virtual Pediatric Systems, LLC. No endorsement or editorial restriction of the interpretation of these data or opinions of the authors has been implied or stated.

The authors would like to thank Dawn Eding, RN; Craig Vandellen, MSW; Dr. Deanna Mitchell; Dr. Surender Rajasekaran; and Dr. Rick Hackbarth, as well as the clinical oncology and PICU staff at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, for their support in the completion of this chapter and various contributions.

The authors would also like to thank Beyond Words, Inc., for assistance with the editing and preparation of this manuscript. The authors maintained control over the direction and content of this article during its development. Although Beyond Words, Inc., supplied professional editing services, this does not indicate its endorsement of, agreement with, or responsibility for the content of the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest or funding sources to declare.

Disclaimer

The opinions and views expressed in this chapter do not in any way reflect the views of Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, other sites of Spectrum Health, other sites affiliated with Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital or Spectrum Health, or the staff employed by Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, Spectrum Health, or any affiliated members.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Leimanis, M.L., Zuiderveen, S.K. (2018). Psychosocial Considerations for Cancer Patients in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit at a Large, Freestanding Children’s Hospital. In: Fitzpatrick, T. (eds) Quality of Life Among Cancer Survivors . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75223-5_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75223-5_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-75222-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-75223-5

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)