Abstract

This paper discusses some problems and questions related to the study of foreign word-formation. German verbs in -ier(en) are used as a case study and as a testing ground for an output-oriented and exemplar-based approach to morphology. I will try to show that Construction Morphology is conceptually and with respect to its central notions very appropriate for the phenomena and the patterns in this domain of word-formation. While I will point out some peculiarities of foreign word-formation, I will also try to show that there is no difference in principle. In essence, word-formation is always an analogical process based on formal and semantic similarities between words and on paradigmatic relationships between (groups of) words.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Foreign word-formation

- Loan morphology

- Construction Morphology

- Morphological schema

- Analogy

- Productivity

- German verb-formation

1 Introduction

I want to thank Geert Booij for many stimulating discussions and for his valuable comments on an earlier version of this contribution.

Borrowing is one of the characteristics of natural languages. Most obviously, language contact results in the adoption of foreign words, but it can also result in the borrowing of word-formation patterns. Bloomfield (1933: 454) already describes the possibility of affix borrowing: “When an affix occurs in enough foreign words, it may be extended to new-formations with native material.” The integration of foreign lexical material is, however, often a partial integration. Words and morphemes tend to keep some of the phonological or grammatical characteristics of the language they are taken from. Therefore, word-formation with foreign elements has often been perceived as largely irregular and unpredictable. This might explain the relative lack of interest on the part of theoretical morphology.

As Eisenberg (2012: 247–250) and Müller (2015: 1615) point out, foreign word-formation has always been the poor cousin of the growing discipline of lexical morphology. Müller himself has been one of the morphologists demanding more attention for the features and the details of foreign word-formation in German. He edited two volumes with articles on diverging aspects of the topic (Müller 2005, 2009), and his own work and work of his research group has provided us with many insights (and many open questions) regarding this part of the lexicon.

In this paper, I will use the verbal suffix -ier in German to illustrate some of the problems and questions related to the study of foreign word-formation. I will point out some peculiarities of foreign word-formation, but I will also try to show that there is no difference in principle with native word-formation.

In essence, word-formation is always an analogical process based on formal and semantic similarities between words, on paradigmatic relationships between (groups of) words and on the creative capacity of language users to come to generalizations and to productively use the analogies they see (Hüning 1999). This is a very traditional conception of word-formation, already formulated in the nineteenth century, for example by Hermann Paul in his famous Prinzipien der Sprachgeschichte (Paul 1920; the first edition appeared in 1880)5. In recent years it faces kind of a revival in usage-based linguistics and in construction grammar approaches to word-formation.

I will adopt a usage-based view on language as a complex adaptive system in the sense of Beckner et al. (2009). In line with Bybee (2010), I will argue in favor of an exemplar-based approach of word-formation, and I will try to show that Construction Morphology (Booij 2010) might provide a model that enables us to better describe what is going on in (foreign) word-formation.

2 Issues in Foreign Word-Formation

2.1 Stratal Peculiarities

With respect to the lexicon and the word-formation in Germanic languages, it is often assumed that we have to deal with a ‘stratal split’, a general division into two ‘strata’, each with its own possibilities and restrictions. For German, Müller (2000: 115) distinguishes indigenous (native) and exogenous (foreign) word-formation. And Booij advocates such a view for Dutch:

Stratal restrictions are a specific kind of lexical restrictions related to the division of the Dutch lexicon into two layers or strata, a native (Germanic) layer, and a non-native (Romance) one. (Booij 2002: 94)

A general restriction concerns the use of foreign suffixes, which are usually only attached to base words of non-native origin. Booij illustrates this behavior with the competing nominal suffixes -iteit (non-native) and -heid (native).

(1) | Native -heid vs. non-native -iteit in Dutch (adapted from Booij 2002: 95) | ||

Native stem | |||

blind ‘blind’ | blind-heid ‘blindness’ | *blind-iteit | |

doof ‘deaf’ | doofheid ‘deafness’ | *dov-iteit | |

Non-native stem | |||

stabiel ‘stable’ | stabiel-heid ‘stableness’ | stabil-iteit ‘stability’ | |

divers ‘diverse’ | divers-heid ‘diversity’ | divers-iteit ‘diversity’ | |

There are exceptions to this rule, but generally speaking, -iteit can only be combined with non-native stems, while -heid can be attached to both native and non-native stems. A similar pattern is found in German (-heit/-keit vs. -ität). As Bauer (1998: 409) points out, languages like Dutch and German tend to be stricter in the separation of native and foreign word-formation patterns than English.

The second important difference between the two types of word-formation has to do with accentuation. While suffixes of Germanic origin are unstressed, those of Romance origin are usually stressed: Dutch stab ie lheid vs. stabilit ei t, German Div er sheit vs. Diversit ä t. Even well integrated loan-suffixes like Dutch -erij and German -erei that do not show the typical restrictions on combinability, reveal their Romance origin because they are stressed (Hüning 1999). Only very old loans like -er (from Latin -arius) do not show this behavior.

2.2 Combining Forms/Confixes

Germanic languages have intensively borrowed from the Romance lexicon, which according to Booij (2002: 95) has “the function of a pan-European lexical stock”. Very often, we find paradigmatically related complex words, like Dutch bibliotheek, German Bibliothek ‘library’ and Dutch bibliofiel, German bibliophil ‘bibliophile’. While -theek and -fiel might be interpreted as suffixes, the first part of these words is not an independent word either. Rather, it is a root that cannot be used independently. Hence, the decomposition of these words and the productive use of their components are a challenge for any account of word-formation that sees the word as the basis of derivational processes.

There are lots of analytical and terminological problems connected to such complex words (see Seiffert 2009 for a discussion). Is the adjective viral derived from the noun virus? Are -al and -us to be seen as suffixes? What is, then, the status of vir? In Germanic languages, it is not a word since it cannot function independently in an utterance. It is a bound element that can be used in combination with other bound elements (like suffixes). ‘Combining form’ is the term usually found in the English literature, but German speaking morphologists often prefer the term Konfix ‘confix’ for these bound elements. Because of its in-between status (not word, not affix) and of the heterogeneity of the members of this category, there has been a lot of discussion about the concept and about the term. This discussion and the still unclear status of the category made scholars like Eins (2008) or Donalies (2009) suggest to avoid the term.

There is, however, agreement about the core members of the category. A prototypical confix like German polit has a non-native origin and a lexical meaning. It is lexicalized, but it is not (or rarely) used independently. Nevertheless, it can be used in compounds (Politdrama ‘political drama’) and it can function as a base for derivation (politisch ‘political’, with resyllabification po·li·tisch).

It is usually seen as a defining feature of affixes that they are attached to words (or word stems) in the formation of new words; affixes cannot be attached to affixes. Confixes, on the other hand, are more flexible in this respect. They are not used independently, but the combination with another bound form can result in a word: the confix naut, for example, can be combined with an affix (naut-ical) and it can also be the second element of a complex word consisting of two confixes (astro-naut, cosmo-naut, aero-naut).

The combination of two confixes (or combining forms) has been discussed extensively in the literature on ‘neoclassical compounds’. Neoclassical compounds consist of Greek and Latin elements but they are not formed in the classical languages; they are formed and used in modern languages. Many of these compounds are international words, like the words with naut, mentioned above, or all the different nouns in -ology for the science or the discipline of what is indicated by the first element (anthropology, philology, theology, etc.).

The status of such words has always been controversial. While most text books assume a class of neoclassical compounds, Lüdeling et al. (2002) claim that neoclassical word-formation does not differ in principle from native word-formation. And Bauer (1998) discusses neoclassical compounds as a prototypical category, also showing that there is much overlap with native word-formation patterns.

A question narrowly connected with notions like confix or neoclassical word-formation is the question of productivity of such patterns. As pointed out by Bauer (1998), the influential position of Dutch morphologists like Schultink and Van Marle has been that word-formation on a foreign basis cannot be productive.

Only those morphological processes may rank as ‘productive’ which (i) can be fully characterized in terms of ‘major lexical categories’, and which (ii) are not restricted to the ‘nonnative’ strata of the lexicon. (Van Marle 1985: 60)

This raises a lot of questions about the nature of ‘productivity’ and, again, about the nature of borrowed word-formation patterns.

2.3 Constructional Schemas

I think that most of the ‘problems’ of foreign word-formation mentioned above, find their place quite naturally in Construction Morphology. I adopt the approach to Construction Morphology as laid out in Booij (2010, 2015). Some of the central notions are also introduced by Booij and Audring (2018). This approach takes a word-based perspective; words are the starting points of morphological analysis. Formal and semantic generalizations about sets of complex words are captured in morphological schemas that express predictable properties of existing complex words, and indicate how new ones can be coined (Booij 2010: 4). This notion of schema is essential for the description of word formation patterns, i.e. the regularities found in word formation. As Booij and Audring (2018) point out: “Morphological patterns, whether productive or unproductive, can be characterized by output schemas.”

As an example, we can come back to our naut-example: While people often will not know the etymology of words like aeronaut, astronaut, cosmonaut etc., they will recognize the pattern, for which the OED formulates the following description: the combining form -naut is used “to form a number of words with the sense ‘voyager, traveller’, with the first element defining the nature of the travel or experience.” We can characterize this generalization in an output schema:

(3) | <[Xi+naut]Nj ↔ [voyager with SEMi indicating the nature of the voyage]SEMj> |

While this schema is mostly a descriptive generalization about existing words, it can also motivate incidental new formations like gendernaut, which is the title of a film about queers and their voyages through the space between man and woman (Gendernauts – A Journey through shifting Identities, 1999).

Output schemas of this kind will be central to my description of German verbs in -ieren.

2.4 Verbal Word-Formation with -ier in German

Derivational morphology offers many suffixes for the formation of new nouns and adjectives in German. Verbal word-formation, on the other hand, is characterized by ‘Suffixarmut’ (suffix poverty), according to Fleischer and Barz (2012: 428). New verbs are formed through conversion and/or prefixation. The exception to this rule of thumb is the verbal suffix -ier. This suffix is borrowed from French in Middle High German; loanwords with this suffix are attested from the thirteenth century onwards (see for the history of the suffix in German, among others, Rosenqvist 1934; Öhmann 1970; Leipold 2006; Scherer n.d.). There are variants of this suffix -ier, that will be dealt with in the next section.

The relatively high frequency of verbs in -ieren has also been noted – and criticized – in the older literature on word-formation in German. Grimm (1864: 343) talked about “die zahllosen verba auf ieren, die […] wie schlingkraut den ebnen boden unsrer rede überziehen” (countless verbs in ieren, that – like twining plants – cover the even surface of our speech). Wilmanns (1899: 114) calls the use of -ieren with German base words a “schlimmer Missbrauch” (a bad misuse). And even Henzen (1965: 228) criticized the excessive use of the pattern for the formation of verbs (“zu viele!”, too many!).

This negative attitude towards word-formation with foreign elements is characteristic of the older literature, not only for -ieren but for foreign elements in general. Nowadays, we find such puristic attitudes especially in the media and in popular scientific writing, and while the criticism is now usually directed against the use of English elements, it used to be directed against loans from Romance languages for a long time.

2.5 The Patterns

The suffix -ier(en) is typically found with non-native bases and in words that are characteristic for specific registers of written language. The resulting verbs differ systematically from ‘regular’ verbs of German. Because of its Romance origin, the suffix is stressed (interpretíeren – er interpretíert) and, therefore, the past participle is formed without the regular prefix ge- (sie hat interpretíert).Footnote 1

Verbs in -ier(en) can be found with corresponding adjectives or nouns as base words (Eisenberg 2012: 291):

(4) | [[x]A+ier]V |

aktivieren ‘to activate’ – aktiv ‘active’ | |

blondieren ‘to bleach, to dye’ – blond ‘blond’ | |

effektivieren ‘to make (sth.) more effective’ – effektiv ‘effective’ | |

fixieren ‘to fix (sth.)’ – fix ‘fixed’ | |

legitimieren ‘to authorize/legitimize’ – legitim ‘legitimate’ |

(5) | [[x]N+ier]V |

attackieren ‘to attack’ – die Attacke ‘the attack’ | |

betonieren ‘to concrete’ – der Beton ‘the concrete’ | |

codieren ‘to code’ – der Code ‘the code’ | |

boycottieren ‘to boycot’ – der Boycott ‘the boycot’ | |

intrigieren ‘to intrigue’ – die Intrige ‘the intrique’ |

Within the group of denominal verbs, we also find verbs that have been formed from an indigenous noun:

(6) | Denominal verbs from indigenous nouns: |

amtieren ‘to hold office’ – das Amt ‘the office’ | |

buchstabieren ‘to spell’ – der Buchstabe ‘the character/letter’ | |

drangsalieren ‘to plague (sb.)’ – die Drangsal ‘the suffering’ | |

gastieren ‘to guest/to make a guest appearance ’ – der Gast ‘the guest’ | |

hausieren ‘to hawk, to peddle’ – das Haus ‘the house’ | |

schattieren ‘to shade’ – der Schatten ‘the shadow’ |

The denominal pattern thus has been used creatively for the formation of new verbs. An interesting thing to note: in some cases the -ieren verb replaces an older verb that had been formed by implicit transposition (conversion), like buchstabieren that replaced from the sixteenth century onwards the older verb buchstaben, or gasten that got replaced by gastieren in the seventeenth century.Footnote 2

Germanic adjectives do appear as base words (halbieren ‘to divide in half’ from halb ‘half’) and sometimes one cannot decide whether a verb is deverbal or denominal (like stolzieren ‘to strut, to prance’ which corresponds to the adjective stolz ‘proud’ as well as to the noun der Stolz ‘the pride’).

The third group consists of root-based complex verbs. The first elements of these verbs cannot be used as words independently, but they can be used in other complex words: neg-ieren, neg-ativ, Neg-ation (‘to negate, negative, negation’).

(7) | Verbs without a corresponding base word (root-based): [x+ier]V |

addieren ‘to add’ –? add | |

dominieren ‘to dominate’ –? domin | |

harmonieren ‘to harmonize’ –? harmon | |

negieren ‘to negate’ –? neg | |

reparieren ‘to repair’ –? repar | |

studieren ‘to study’ –? stud |

This is, according to Eisenberg (2012: 291), by far the largest group of verbs in -ieren.

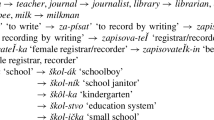

That most verbs in -ier(en) do not have existing words as their bases does not mean that they are not motivated at all. We can link them to other complex words in order to motivate the form and the meaning of these verbs. Even if we do not know what emigr might mean, we do recognize it as the string that keeps together words like emigrieren ‘to emigrate’, Emigrant ‘emigrant’, and Emigration ‘emigration’. These words are part of a network of paradigmatic relations between words (Fig. 1).

Other roots tightly integrate in this network: inform-ieren, Inform-ation, Inform-ant, inform-ativ. However, not all use exactly the same forms: invest-ieren, Invest- i tion; selekt-ieren, Selekt-ion, selekt-iv. This suggests that other segmentations are possible as well. If we assume a morpheme iv, we would get oper-at-iv, and the element at could also be assumed for Inform-at-ion and Demonstr-at-ion, if we want to see ion as a morpheme. Alternatively, one might want to assume allomorphy (of the affixes or of the stems).

Confixes like neg or emigr do not have a meaning on their own, but only as a component of paradigmatically related complex words that are motivated by each other. Emigrant and Demonstrant can be paraphrased by using the corresponding verbs (‘ein Emigrant ist jemand der emigriert’), and by comparing the words in -ant, language users can infer the nomen agentis-meaning. The means that the relation between the nouns Demonstrant and Demonstration is as important as the one with the verb demonstrieren for the proper understanding and usage of these words. These relations do not have predictive power in the strict sense. We could predict an agentive noun Operant from the existence of Demonstrant and Emigrant, but this noun does not exist in German. Its function is already fulfilled by another form: der Operateur (or Operator). But if it were formed, it would not be too difficult to interpret within a certain context, through the analogical relations with other words with an agentive meaning.

In morphology, we often focus on the derivational relation between base word and complex word. The study of foreign word-formation with so-called confixes suggests that this derivational relation is not the only and probably not even the most important relation, at least for the interpretation of complex words.

There are lots of root-based morphological patterns in which the morphemes involved do not have a meaning by themselves. Booij and Audring (2018) discuss some examples from Dutch that show the necessity of word-based instead of morpheme-based morphology. They use constructional schemas for stating regularities that are not productive, schemas that have a motivational function. And it is such an output-oriented view that is most useful in foreign word-formation, too. The structure and the meaning of a complex word can be captured through the (multiple) motivation it gets from its place in the ‘construct-i-con’, to use Goldbergs well-known term for the network of constructions that captures our knowledge of a language (Goldberg 2003).

If we want to formalize the relationship between the different patterns, we might use a circular variant of what is known as ‘second order schema’ in Construction Morphology. Second order schemas are used by Booij (2017) to paradigmatically link two constructional schemas by means of co-indexation. In our case, this would look like this:

(8) | <[[x]i ier]Vj ↔ [to undertake SEMk]SEMj>≈<[[x]i ation]Nk ↔ [the event/action of SEMj]SEMk> |

The ≈ sign is used to express the paradigmatic relationship between the two schemas and between hundreds of root-based derivatives, these schemas stand for, like:

(9) | deklarieren ‘to declare’ – Deklaration |

designieren ‘designate’ – Designation | |

dissimilieren ‘dissimilate’ – Dissimilation | |

evaluieren ‘evaluate’ – Evaluation | |

emanzipieren ‘emancipate’ – Emanzipation |

The schema in (8) could be extended with other elements, paradigmatically related to the verb and the noun (e.g. a schema for corresponding adjectives in -ativ). The words are related through the root element (x) and their meaning is dependent from (and motivated by) the other elements in the paradigm in which the word has its place.

2.6 The Function of -ier

Output orientation means that we focus on the similarities between complex words. This includes in our case the obvious observation that, regardless of the category of the base word (or root), the verbs share a formal element, the string ieren at the end of the word, and their part-of-speech category. Thus, the general function of -ier is that of a verbalizer: it signals a verbal stem that can be followed by the infinitive marker -en or another inflectional ending (ich buchstabier-e, du buchstabier-st, sie buchstabier-t, etc.). The resulting verb can be transitive (like reparieren ‘to repair’) or intransitive (like amtieren ‘to officiate’).

The most general schema for these verbs, therefore, has the form [x+ier]V. It has two subschemas that specify the part of speech of the x-element (adjective or noun). They all share the verbalizing function, but it is not possible to find a common meaning for all verbs in -ieren.

Let us, therefore, look at the subschema in which the first element can be identified as an adjective. Within this category, it is possible to identify a group of verbs that can be characterized as causative verbs: they denote an action/event that results in some kind of state that can be characterized by the adjective: aktivieren means ‘to make so./sth. aktiv (active)’, legitimieren means ‘to make so./sth. legitim (legitimate)’. For these verbs, we can assume a subschema:

(10) | <[[x]Ai+ier]Vj ↔ [to make so./sth. SEMi]SEMj> |

Within the group of denominal verbs, however, it is difficult to find some kind of a common function/semantics (Fuhrhop 1998: 73).Footnote 3 This lack of “begrifflich-semantische Eigenständigkeit” (conceptual-semantic autonomy) of -ier- might, according to Fleischer (1997: 77), be responsible for the pairs of verbs with and without -ier-:

(11) | Chlor ‘chlorine’ | – chloren | chlorieren ‘chlorinate’ |

Filter ‘filter’ | – filtern | filtrieren ‘filter’ | |

Kontakt ‘contact’ | – kontakten | kontaktieren ‘contact’ | |

Lack ‘lacquer, paint’ | – lacken | lackieren ‘lacquer’ | |

Sinn ‘sense’ | – sinnen | sinnieren ‘ponder’ |

These verbs have been formed in German on the basis of an existing noun, but there is no coherent semantics, that would distinguish the converted verbs from those in -ieren.

Therefore, Fuhrhop (1998: 138) called -ier(en) an ‘Eindeutschungsendung’, which means that its main (and in many cases only) function is to integrate the word into the German verbal system. Beyond that, the suffix does not have a specific semantic function, and Fuhrhop claims that the pattern is (therefore?) not productive synchronically. This view is endorsed by Eisenberg, who argues that -ier has the function to make foreign stems fit into the German system. To the left of -ier are the non-native elements, to the right are the native elements, which means that the stems with -ier are not only accessible to inflection, but also to the word-formation processes typical for the verbs in the Germanic part of the lexicon (Eisenberg 2012: 293).

Therefore, a verbal stem like interpretier can easily be used with the suffix -bar: interpretierbar. Subsequently, this adjective can be the basis for nominalization (Interpretierbarkeit ‘interpretability’). In computer jargon we also find die Bytecode-Interpretierung and der Interpretierer (which is not a person but a computer program). English does not need such a verbal ending to produce a suitable verbal stem. It uses the root interpret as a verbal stem and also as a base for further derivation: interpretable, interpreting, interpreter. In German, on the other hand, derivational forms like *interpretbar and *Interpretung are not possible.Footnote 4

Another example of this contrast is that while English uses convert as the verbal stem to which inflectional as well as derivational endings can be attached (he convert-s, convert-ing, convert-er, convert-ible), German needs the verbalizer -ier in order to make such complex words possible: er konvert-ier-t, Konvert-ier-ung, Konvert-ier-er, konvert-ier-bar, etc.

A foreign root can be used as a basis for the formation of nouns, but only with foreign suffixes: Akkumul-ation (‘accumulation’) is possible, but (synonymous) nominalization with -ung is only possible when the corresponding verb in -ier(en) is available: akkumul-ier-en – Akkumul-ier-ung. More examples: while we can have an agent noun commander in English, the German equivalent uses non-native suffixes -ant or -eur (Kommandant, Kommandeur). The suffix -er is possible in German only after the verbalizing -ier: Kommandierer. And parallel to the verbs zit-ier-en and refer-ier-en, we find nouns with non-native formatives: Zit-at ‘citation’, Refer-ent ‘speaker’. Native suffixes are only possible with the verbal stem in -ier (Zit-ier-ung, refer-ier-bar). This can lead to near-synonyms like Illustr-ier-ung and Illustr-ation, or diskut-ier-bar and diskut-abel (Fleischer 1997: 78). The suffix -ier has been used not only as a verbalizer for Romance roots, but for loans from English, too. An example is German train-ier-en from English to train.

The English verb to boycot has been borrowed at the end of the nineteenth century. In the beginning it had the form boycotten (as still in Dutch), but around 1900 the verb had already been ‘germanized’ by using the originally French suffix: boykottieren, which then made possible further derivation like Boykottierung, boykottierbar.

There is some limited regional variation with respect to the form of some verbs borrowed from English: Swiss German has grillieren, rezyclieren and parkieren instead of grillen ‘to have a barbecue’, recyceln ‘recycle’ and parken ‘to park’, which are the forms used in Germany (Ammon et al. 2016).Footnote 5

Nowadays, the ‘Eindeutschungssuffix’ does not seem to be necessary any more, verb-formation with -ier has become largely unproductive (Koskensalo 1986; Fuhrhop 1998). New loanwords from English are usually integrated into German directly: box-en, design-en, layout-en, scann-en, etc. They all allow for the formation of agentive or instrument nouns (Design-er, Scann-er) or for adjective formation with -bar (ein gut scannbarer Text). With respect to productivity, -ier differs from its variants, which can very well be used productively.

3 Variants of -ier(en)

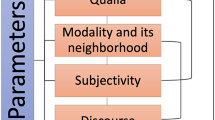

If we take an exemplar-based approach and compare the different verbs in -ier(en), we can identify two ‘extended forms’: -isier(en) and -ifizier(en). This process of inductive generalization is in line with Bybee’s idea of emergent morphological relations (e.g. Bybee 1988, 2010: 22 ff.) as illustrated in Fig. 2.

In text- and handbooks, the forms are usually lumped together, most probably because they do not seem to have any specific semantics. This happens for example in Deutsche Wortbildung (Kühnhold and Wellmann 1973), in Elsen (2011: 231) and in Fleischer and Barz (2012: 432).

Fleischer (1997: 84), on the other hand, does not want to see -isier(en) and -ifizier(en) as variants of -ier(en), but as separate suffixes, on morpho-syntactic and structural grounds. They do, indeed, differ from other -ier(en) verbs quite fundamentally, mainly because they are all transitive. This makes them behave more homogeneous syntactically and with respect to further word-formation. Most verbs with -isier and -ifizier allow for further derivation with -ung (Modern-isier-ung, Stabil-isier-ung, Ident-ifizier-ung), and because they are transitive, derivation with -bar is also possible (modern-isier-bar, stabil-isier-bar, ident-ifizier-bar). With -ier(en) verbs, this is much less regular (cf. *Blamierung, *blamierbar, *Stolzierung, *stolzierbar, *Fotografierung,? fotografierbar).

An important question concerns the structure of a verb like identifizieren. What is the stem, what is the affix? Is -ifizieren one morpheme or a combination of more than one morpheme? Compare the nominalizations Identifikation, Personifikation, Spezifikation with Konzentration, Demonstration. Above, we splitted the latter words into two parts/morphemes: Konzentr-ation, Demonstr-ation because of their link with konzentr-ieren and demonstr-ieren. If we assign morpheme status to ation, the logical consequence is to split up the sequence ifizier into two parts.

(12) | Segmentation problems |

Ident-ität ‘identity’ | |

ident-isch ‘identical’ | |

ident-ifiz-ier-en ‘identify’ | |

Ident-ifiz-ier-ung ‘identification’ | |

Ident-ifiz/k-ation ‘identification’ |

We get a confix (ident) and some suffixes. But what is the status of ifiz (and ifik). What would be its function? Does this element somehow contribute to the meaning of the complex verb? Should we assume stem-allomorphy (identifiz)? Or do we analyze -ifizier to be an allomorph of -ier? But what would, then, be the condition under which the allomorph is used? After all, we have other stems in -ent that take -ier as a verbalizer: komment-ier-en ‘comment’, implement-ier-en ‘implement’.

With respect to the Dutch counterpart of -isier, Booij (2016) also discusses this segmentation problem. He seems to be quite confident about splitting -iseer into two parts:

The suffix -iseer is a combination of the morphemes -is- and -eer, as can be concluded from the way in which deverbal nouns are formed: the suffix -eer is replaced with the suffix -atie, and this also applies to verbs ending in -iseer: modern-is-eer − modern-is-atie ‘modernization’ (only the part -eer is replaced). (Booij 2016: 2444)

The analysis seems plausible, but one has to ask what the status is of is, since it does not have any kind of obvious semantic function and it is not easy to find a phonetic reason for its presence either (compare the adjective modern with intern, and notice that the verbalization of the latter is done without -is-, i.e. with -eren in Dutch and with -ieren in German, interneren/internieren).

This might suffice to illustrate some of the problems of a morpheme-based approach to foreign word-formation. The exemplar-based network-approach, on the other hand, allows for generalizations that do not rely on the notion of morpheme. In the words of Bybee (2010: 23): “One advantage of this approach to morphological analysis is that it does not require that a word be exhaustively analysed into morphemes.” An output-oriented and word-based perspective avoids many problems of the morpheme- and rule-based approaches.

Nevertheless, language users do recognize similarities and they do group together words on the basis of formal correspondences. While all words in -ier(en) share the verbalizing function, the ‘short’ and the ‘long’ forms correspond to other differences, especially with respect to productivity. While the general -ier(en) pattern is hardly productive anymore, the patterns with the extended variants are used for the formation of new words.

3.1 Verbs in -isier(en)

Verbs with -isier have a stress pattern that makes them differ from the verbs we were dealing with up to now. Since the first i is unstressed, the verb stems always end in a iamb. Stress clash which is common with derivation in -ier (e.g. fíx-íer) is absent. Furthermore, they are transitive (as mentioned above), with only very few exceptions (one such exception is theoretisieren ‘theorize’).

The verbs in -isier(en) quite systematically correspond to verbs in -ize in English. In this respect, they differ from verbs in -ier(en) which are usually equivalent to bare stems in English:

(13) | German -ieren and English stems |

exekut-ieren – to execute | |

inform-ieren – to inform | |

interpret-ieren – to interpret | |

konklud-ieren – to conclude |

(14) | German -isieren and English –ize |

dämonisieren – to demon-ize | |

organ-isieren – to organ-ize | |

real-isieren – to real-ize | |

sozial-isieren – to social-ize |

This difference corresponds with an etymological difference: while the verbs in (13) are loans from French, the German -isier and English -ize in (14) have their origin in Greek:

(15) | Greek -ίζειν (-izein) → Latin -izāre, -īzāre → French -ise-r, Italian -izare, Spanish -izar |

Most of the existing words have a non-native derivational base (Greek or (Early Modern) Latin). It is often impossible to tell whether they are borrowed from Greek, Latin or French. They could also be analogical formations, built after Latin or French examples.

In German, verbs in -isier(en) appear from the sixteenth century onwards. The group is largely expanded during the eighteenth and the nineteenth century (Marchand 1969; Fleischer 1997). For verbs in -isier(en) different groups can be distinguished, cf. Fuhrhop (1998: 75) and Eisenberg (2012: 291/2). The verbs in the first group have a corresponding noun:

(16) | Denominal verbs in -isier(en) |

alphabet-isieren ‘alphabetize’ | |

charakter-isieren ‘characterize’ | |

katalog-isieren ‘catalogue’ | |

organ-isieren ‘organize’ | |

pulver-isieren ‘pulverize’ |

Some verbs show an epenthetic t after the noun, which is not only found in the verb but also in the corresponding adjective in -isch:

(17) | Drama ‘drama’ – dramatisch – dramatisieren |

Schema ‘schema’ – schematisch – schematisieren | |

Narkose ‘narcosis’ – narkotisch – narkotisieren |

The next group consists of verbs that can be analyzed as deadjectival:

(18) | Verbs in -isier(en) that correspond to an adjective synchronically |

digital-isieren ‘digitize’ | |

funktional-isieren ‘functionalize’ | |

legal-isieren ‘legalize’ | |

mobil-isieren ‘mobilize’ | |

modern-isieren ‘modernize’ | |

radikal-isieren ‘radicalize’ | |

stabil-isieren ‘stabilize’ |

Semantically, the verbs in (18) form a quite homogenous group. Their meaning can be described as ‘to make something X’ (where X stands for the adjective).

There are no clear-cut criteria for the choice of -isier instead of -ier, but there are preferences. Adjectives in -l have a strong preference for -isier. And within this group, the adjectives with -il (mobil ‘mobile’, steril ‘sterile’) and especially those ending in -al (legal ‘legal’, national ‘national’) form coherent subgroups. There are only a few exceptions (like nasal-ieren ‘nasalize’). Adjectives in -ell join the -alisieren group:

(19) | generell – generalisieren ‘generalize’ |

individuell – individualisieren ‘individualize’ | |

kommerziell – kommerzialisieren ‘commercialize’ |

The stem in -al serves as an allomorph, used in derivational word-formation processes (Individual-ität ‘individuality’, Individual-ismus ‘individualism’) and in compounds (Individual-tourismus ‘individual tourism’, General-verdacht ‘universal suspicion’, Kommerzial-rat ‘councilor of commerce’).Footnote 6

Verbs corresponding to adjectives are part of a bigger network of paradigmatic relations. Almost all adjectives in -al and many of the other adjectives also allow for the derivation of a noun in -ität: Banalität, Legalität, Mobilität, Stabilität etc. (but not *Privatität; the corresponding noun is Privatheit). At the same time, nominalization of the verbal stem is possible, too: Digital-isier-ung, Modern-isier-ung, Mobil-isier-ung, Stabil-isier-ung, etc. Since the verbs are transitive, the formation of -bar adjectives is also possible for all those verbs.

In addition to these groups where a corresponding base word can clearly be identified, we find other interesting series of verbs in -isier(en) for which the identification of the base is not that obvious.

One group of such verbs consists of words with a confix as their first element. Usually, these verbs correspond to adjectives in -isch from the same confixes. Sub-groups can be formed, when the corresponding noun is taken into account (they often end in -ik, -ie or -ität).

(20) | Root-based verbs with corresponding adjective in -isch | ||||

root/confix | noun | adjective | verb | ||

botan | Botan-ik | botan-isch | botan-isieren | ‘to botanize’ | |

krit | Krit-ik | krit-isch | krit-isieren | ‘to criticize’ | |

polem | Polem-ik | polem-isch | polem-isieren | ‘to polemize’ | |

polit | Polit-ik | polit-isch | polit-isieren | ‘to politicize’ | |

techn | Techn-ik | techn-isch | techn-isieren | ‘to mechanize’ | |

solidar | Solidar-ität | solidar-isch | solidar-isieren | ‘to solidarize’ | |

demokrat | Demokrat-ie | demokrat-isch | demokrat-isieren | ‘to democratize’ | |

harmon | Harmon-ie | harmon-isch | harmon-isieren | ‘to harmonize’ | |

There is a partial overlap with the denominal verbs in (17) that correspond to -isch adjectives: Drama, Dramatik, dramatisch, dramatisiseren.

The correspondence with adjectives in -isch is characteristic of the last group, too. It contains verbs, based on special derivational stem forms of proper nouns. These nouns are mostly names of countries or for (groups of) people.

(21) | Afrika – afrikan-isch – afrikan-isieren ‘to Africanize’ |

Amerika – amerikan-isch – amerikan-isieren ‘to Americanize’ | |

Freud – freudian-isch – freudian-isieren ‘to Freudianize’ | |

Hegel – hegelian-isch – hegelian-isierung ‘to Hegelianize’ |

The resulting verbs often end in -anisier(en) (but not always, as französisieren ‘to make French’ illustrates). Formally and semantically, the verbs in (20) and (21) can be related to the corresponding -isch-adjectives. Their meaning can be paraphrased as ‘to make so./sth. X’ (where X stands for the adjective). But, of course, the verb-meaning is also related to the corresponding noun: ‘to make so./sth. show characteristics that are stereotypically linked to country X or to person X’.

Verbs like japanisieren join this group, as they also have a corresponding adjective in -isch (japanisch ‘Japanese’), but in these cases, there is no special stem allomorph involved. Japanisieren or taiwanisieren could also be derived from the country name directly.

(22) | ‘Sicher können wir von anderen lernen, aber amerikanisieren, japanisieren, taiwanisieren läßt sich das Modell Deutschland nicht.’ (Die Zeit, 05.12.1997, via DWDS) |

[Of course, we can learn from others, but the model Germany cannot be amerikanized, japanized, taiwanized.] |

Japanisieren forms the bridge to other deonymic verbs that have to be seen as denominals: formally, finnlandisieren (‘finlandize’) has to be related to the name of the country (Finnland), since the corresponding adjective shows umlaut: finnländisch. Similar is hollandisieren (Holland, holländisch):

(23) | ‘[…] und van Gaal dürfte den FC Bayern dann weiter hollandisieren.’ (Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger, 10.06.2009, http://www.ksta.de/12647928) |

[… and van Gaal will probably further hollandize FC Bayern] |

Furthermore, some of the -isch-adjectives serve as language names at the same time: Französisch ‘French’, Koreanisch ‘Korean’, Norwegisch ‘Norwegian’, Polnisch ‘Polish’, Ungarisch ‘Hungarian’, etc. These can also be turned into verbs:

(24) | ‘Noch in den sechziger Jahren fühlten Schauspieler sich verpflichtet, ihre Namen zu “ungarisieren”, wenn sie nicht ungarisch klangen.’ (Die Zeit, 1999, http://www.zeit.de/1999/42/199942.l-ungarn_.xml/seite-2) |

[In the sixties, actors still felt obliged to hungarize their names, if they did not sound Hungarian.] |

(25) | ‘Während in Südkorea englische und chinesische Wörter oft einfach übernommen werden, will das nordkoreanische Regime alles koreanisieren […]’ (taz, 10.02.2016, http://www.taz.de/!5272550/) |

[While in South Korea English and Chinese words are often simply adopted, the North Korean regime wants to koreanize everything.] |

Again, the meaning of these verbs can be characterized as causative/resultative: ‘to make sth. look/sound (more) X’ (where X is the adjective that can also be used as language name).

There are many more peculiarities and idiosyncrasies to be observed with these verbs but in this context, the more interesting part is that we do find some generalizations and patterns within this complex network of paradigmatic relations between (groups of) nouns, adjectives and verbs in -isieren.

3.2 Verbs in -ifizier(en)

The verbs in -ifizieren join the -isieren verbs, but it is difficult to find criteria for the distribution of both forms. The -ifizieren verbs form a small group, the verbs have foreign words or roots (confixes) as bases. With -ifizier, the suffix gets longer again, it gets another, third syllable; stress is attracted to the third syllable (ier). The English equivalent usually is -ify; etymologically we have to think of Latin -ificare as its origin (as in personificare, German personifizieren, Dutch personificeren, English personify).Footnote 7

(26) | Verbs in –ifizieren |

falsifizieren ‘falsify’, glorifizieren ‘glorify’, identifizieren ‘identify’, modifizieren ‘modify’, mumifizieren ‘mummify’, qualifizieren ‘qualify’, simplifizieren ‘simplify’, spezifizieren ‘specify’, verifizieren ‘verify’ |

The verbs share the causative, transitional meaning with the verbs in -isieren. As Fuhrhop (1998: 76) points out, there is some rivalry between both forms: polnisieren and polnifizieren (from Polen ‘Poland’) can be used synonymously. There are some new words with -ifizier(en), formed in German. Fuhrhop mentions russifizieren ‘russify’ or (ent)nazifizieren ‘(de)nazify’. One might want to add gentrifizieren ‘to gentrify’.

Since russisieren is not possible, Fuhrhop suggests to view -ifizier(en) as an allomorph for -isier(en), to be used after alveolar fricatives, for the formation of new verbs (cf. klassifizieren ‘classify’, spezifizieren ‘specify’). Given the limited number of examples, this is hard to prove (or refute).

3.3 Productive Use of -isier(en)

As already mentioned, the -isier(en) pattern can be used productively with a causative meaning. The resulting verbs denote some kind of transition from one state into another, which is indicated by the corresponding adjective or noun. This can be accounted for by assuming a subschema that characterizes the productive pattern within the large group of -(is)ieren verbs:

(27) | <[[X]i+isier]Vj ↔ [cause so./sth. to become/behave/be more like SEMi]SEMj> |

This schema can be further specified with respect to the X slot. It is especially the group of verbs that can be related to (proper) nouns that has become quite productive. The X slot can, for example, be taken by toponyms in order to express a transition of someone or something getting some characteristics typically related to X.

(28) | ‘Wenn wir Pech haben, dann wird der Rest der Republik aber berlinisiert, und das wäre dann das Ende.’ (Die Welt, 07.01.2015, https://www.welt.de/kultur/article136110516/) |

[If we are unlucky, the rest of the republic will be berlinized, and that would be the end.] |

(29) | ‘Rührend zu sehen, wie die Illustrationen ‘chinaisiert’ wurden: Maria und der Engel Gabriel als Chinesen.’ (Merkur, 25.03.2009, https://www.merkur.de/kultur/chinaleidenschaft-107084.html) |

[Touching to see how the illustrations have been ‘china-ized’: Maria and the Angel Gabriel as Chinese.] |

Besides toponyms, proper nouns that denote (groups) of people with special characteristics can function as base words for the productive schema. Names of politicians or VIPs are used frequently in this construction:

(30) | ‘Trotz der dummen Attacken einiger französischer Sozialisten gegen Angela Merkel scheint sich Präsident Hollande selbst zu merkelisieren.’ |

(Die Welt, 29.07.2013, https://www.welt.de/print/die_welt/debatte/article118466633/Merkel-Daemmerung.html) | |

[Despite of the stupid attacks of some French socialists on Angela Merkel, pesident Hollande seems to Merkel-ize himself.] |

(31) | ‘Selbst in der Türkei […] zeigt sich immer mehr, dass der angeblich gemäßigte Islamismus Recep Tayyip Erdoğans die Demokratie zunehmend “putinisiert”, also zu einer Farce degradiert.’ (Blog Ortner Online, 30.08.2017, http://www.ortneronline.at/?p=24047) |

[Even in Turkey, it shows that the allegedly moderate islamism of Erdoğan increasingly Putin-izes democracy, i.e. degrades it to a farce.] |

The denominal pattern is, however, productive not only with names, but with other nouns, too. They all express a transitional meaning.

(32) | Productive use of denominal -isier(en) |

computerisieren ‘to computer-ize’ | |

hipsterisieren ‘to hipster-ize’ | |

pornoisieren ‘to porn-ize’ | |

typisieren ‘to typ-ify’ |

These facts all show the productivity of -isier(en).

3.4 Verbs in -isier(en) and Nouns in -isierung

The productive formation of verbs in –isier(en) is closely linked to the formation of nouns in -isierung. The question is, then, whether these nouns have to be seen as secondary derivations on the basis of the (possible) verbs.

Wilss (1992) examined the productive use of German nouns in -isierung. He found hundreds of examples, deadjectival ones like Brutalisierung ‘brutalization’, Digitalisierung ‘digit(al)ization’ or Humanisierung ‘humanization’ and denominal ones like Automatisierung ‘automation’, Kanalisierung ‘canalization’ or Motorisierung ‘motorization’. More often than not, such nouns are (much) more frequent than the corresponding verbs. The nouns are characteristic for present-day German. They belong especially, but not exclusively, to German jargon (special, technical language).

Wilss already used the notion of ‘schema’ to account for these nouns. He pointed out that they usually stand in a paradigmatic relationship with the corresponding verbs in -isieren which, however, not always get realized. Therefore, he calls -isierung a suffix and he does not want to see this process of noun formation as secondary, since it is “praktisch unentscheidbar, ob das Substantivsuffix das Verbsuffix nach sich gezogen hat oder umgekehrt” [virtually undecidable, whether the noun suffix entailed the verb suffix or vice versa] (Wilss 1992: 232).Footnote 8

Construction Morphology has a proper way of handling this problem. It acknowledges that speakers might use shortcuts when coining new complex words and accounts for these short cuts with schema unification (Booij 2010: 41–50).

(33) | [N-isier]v + [V-ung]N → [[N-isier]V -ung]N |

These unified schemas match the output of the productive pattern without necessarily presupposing the existence of the verb in -isier. It is possible to form this verb, but there is no need that it is known to the language user as an independent word when coining the complex formation in -isierung.

Kempf and Hartmann (2018) demonstrate the usefulness of the concept of schema unification from a diachronic perspective. The suffix -ung is one of their cases, and they point out that this suffix is losing its productivity, as we know from Demske (2000). The suffix is, however, productively used in contexts, where the verb itself is complex, especially in combination with a prefix. This can be accounted for by using embedded and unified schemas, as demonstrated by Kempf and Hartmann (2018).

I would like to add the case of nouns in -isierung to their argumentation, which, I think, also nicely demonstrates the necessity and usefulness of unified schemas in morphological theory. Let me mention some more examples to illustrate this point.

Next to the place name Berlin, we see the verb berlinisieren in (28) and we also find the corresponding noun:

(34) | ‘Afrika-Konferenz: 130 Jahre Berlinisierung eines Kontinents und Einübung ins Verbrechen’ (Volksbühne Berlin, 2015, http://www.volksbuehne-berlin.de/praxis/afrika_konferenz/) |

[Africa-conference: 130 years of Berlin-ization of a continent and of exercising for crime] |

Berlin is, of course, referred to metonymically in this case and stands for the nineteenth century German empire. If we take another German place name, Dresden, we can easily find examples for the derived noun, but not for the corresponding verb.

(35) | ‘“Gegen die Dresdenisierung Leipzigs” hatten einige junge Leipziger am Waldplatz auf ihr Transparent geschrieben.’ (taz, 14.01.2015, http://www.taz.de/!239558/) |

[‘Against the Dresden-ization of Leipzig’ some young inhabitant of Leipzig had written on their banner at the Waldplatz.] |

The same is true for country names like Bangladesh.

(36) | ‘Wenn dann die Wirtschaft angekurbelt worden ist, kann Griechenland auch Schulden zurückzahlen. Mit der bisher verfolgten Bangladeshisierung wäre das unmöglich.’ (Spiegel Online, 01.02.2015, http://www.spiegel.de/forum/politik/pressekompass-tsipras-gegen-die-eu-das-sagen-die-medien-thread-229699-3.html) |

[Once economy has been boosted, Greece can repay the loan. With the Bangladeshization followed to date, this would be impossible.] |

The pattern seems to be very productive with nouns referring to well-known personalities, too. Politicians are one of the source domains for this kind of word-formation. Some examples (via Google):

(37) | die Merkelisierung Europas ‘the Merkel-ization of Europe’ |

die Schröderisierung der Sozialdemokratie ‘the Schröder-ization of social democracy’ | |

die Westerwellisierung der FDP ‘the Westerwelle-ization of the FDP’ | |

die Berlusconisierung der Kulturpolitik ‘the Berlusconi-ization of the cultural policy’ | |

die Trumpisierung der deutschen Sprache ‘the Trump-ization of the German language’ |

In Westerwellisierung and Berlusconisierung the final vowel of the name is deleted before the suffix, which is unproblematic as long as the word ends in –isierung, and as long as the name is recognizable, at least in the context in which it is used. In the context of the Dutch elections in 2017, German media repeatedly used constructions like die Wilderisierung der Politik. No problem, since the name of Geert Wilders was sufficiently recognizable, despite the stripping of the last consonant. Another example:

(38) | ‘Die Wilderisierung Ruttes ist nur die halbe Wahrheit.’ |

(Rheinische Post, 17.03.2017, http://www.rp-online.de/politik/eu/der-deich-hat-gehalten-aid-1.6695035) | |

[The Wilder(s)-ization of Rutte is only half of the truth.] |

Again, in examples like these the nouns in -isierung are much more frequent than the corresponding verbs, and for many nouns a corresponding verb is not attested at all. The usual search engines will return dozens of examples of (Helmut-)Kohlisierung, but even Google won’t find more than an incidental example of kohlisieren.

Besides names of well-known politicians, other VIP names are also possible as base words for this derivational pattern. The Kim-Kardashianisierung der Politik (‘Kim Kardashianization of politics’) is such an example, or the Kardashianisierung des Pop:

(39) | ‘Beinahe unbemerkt von den Augen und Ohren der Öffentlichkeit hat die Kardashianisierung des Pop begonnen: Selbstbespiegelung als einzig erlaubtes Thema. Kim Kardashian ist Kim Kardashian ist Kim Kardashian.’ (Süddeutsche Zeitung, 28.11.2016, http://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/starboy-von-the-weeknd-wie-ein-selfie-von-kim-kardashian-1.3270175) |

[Almost unnoticed by the eyes and the ears of the public, the Kardashianization of pop has started: self-reflections as the only permitted subject. Kim Kardashian is Kim Kardashian is Kim Kardashian.] |

Other examples (via Google):

(40) | die Löwisierung des deutschen Fußballs ‘the Löw-ization of German soccer’ |

die Karajanisiserung des Musikbetriebs ‘the Karajan-ization of the music business’ | |

die Pavarottisierung des Pop ‘the Pavarotti-ization of pop’ | |

die Schweigerisierung der deutschen Komödie ‘the Schweiger-ization of the German comedy’ |

Such nouns can also be completed with the first name: die Til Schweigerisierung des deutschen Films ‘the Til Schweiger-ization of the German film’ is used, too. And the Helene-Fischerisierung of Germany is bemoaned by many people. Spelling is flexible in these cases: Helenefischerisierung, HeleneFischerisierung, Helene-Fischerisierung or Helene Fischerisierung are all attested.

Complex words in -isierung are also possible from brand names and from other nouns that represent some stereotypical concept. De Gruyter has a book called Die Googleisierung der Informationssuche (2014) ‘the Google-ization of information retrieval’ (sometimes spelled as Googelisierung or Googlisierung, which corresponds to an altered pronunciation, omitting the sjwa). Other examples relate to trends in the coffee business:

(41) | ‘Der schleichende Trend zur Tchiboisierung des Buchhandels vollzog sich bislang langsam aber sicher.’ |

(WAZ, 4.11.2011, https://www.waz.de/staedte/essen/thalia-und-mayersche-setzen-auf-teelichter-und-fruehstuecksbrettchen-id6045605.html) | |

[The trend towards Tchibo-ization of the book store took place slowly but surely.] |

(42) | ‘An den Kommerz, das überall Gleiche, die Kettenläden-Ketten, die Starbuckisierung der Zentren hat man sich nicht bloß in Berlin gewöhnt.’ |

(Der Tagesspiegel, 30.01.2017, http://tagesspiegel.de/politik/boomtown-berlin-am-ende-die-hauptstadt-leidet-unter-ihrer-normalitaet/19318566.html) | |

[Not only in Berlin, one got used to commerce, everywhere the same, the chain stores, the Starbuck(s)-ization of the centres.] | |

(43) | ‘Und auch über die Cappuccinisierung der Gesellschaft oder die internationalen Ketten mit ihrer Pappbecherkultur, sei es in Wien oder in Berlin, rümpft er nicht die Nase.’ |

(Deutschlandfunk Kultur, 07.01.2016, http://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/wiener-kaffeehauskultur-in-berlin-herr-ober-einen.1001.de.html?dram:article_id=341702) | |

[And he also doesn’t turn up his nose at the Cappuccin(o)-ization of society or at the international chains with their paper cup culture, in Vienna as well as in Berlin.] | |

(44) | ‘Und weil St. Paulianer bekanntlich nicht auf den Mund gefallen sind, schimpfen sie im Film ordentlich gegen die Lattemacchiatisierung ihres Stadtteils an.’ |

(Spiegel Online, 07.05.2009, http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/kino/st-pauli-dokumentation-vom-rotlichtviertel-zur-sahnelage-a-623399.html) | |

[And because the people of Sankt Pauli are never at a loss for words, they rant and rave against the Lattemacchiat(o)-ization of their district.] |

Again, we see the reduction at the end of the base word (Starbuck s , cappuccin o , latte macchiat o), to make the nouns fit better into the pattern.

As Wengeler (2010) pointed out, some names of persons of public interest, give rise to whole series of derivations in the media. As a near synonym of Merkelisierung, we find the Vermerkelung (of something or somebody) and the contamination of both patterns is found, too: Vermerkelisierung. Footnote 9 Of course, we also have Merkelismus ‘Merkel-ism’ and its supporter is the Merkelist or the Merkelianer. An interesting form is Merkelantismus, which, apparently, alludes to Merkantilismus ‘mercantilism’. Examples with these and more derivatives can easily be found via Google. Furthermore, Merkel is, of course, the first element in a vast number of nominal compounds (der Merkel-Besuch ‘the Merkel visit’, das Merkel-Zitat ‘the Merkel quote’; cf. recent work by Barbara Schlücker on proper names in compounds, e.g. Schlücker (2017)).

3.5 Derivation vs. Conversion

With respect to verbs in -isieren, it is remarkable, that it is also possible to create another verbal form by conversion: merkeln. Apparently, there is a functional split between both patterns: while merkelisieren is transitive, conversion leads to an intransitive or reflexive verb. Merkeln has been on the shortlist for the ‘Jugendwort 2015’ and the jury described its meaning as ‘doing nothing, not making a decision’ (http://www.stern.de/familie/kinder/jugendwort-2015--die-top-30-bitten-zur-wahl-6356488.html). It can also be used in compounds like rummerkeln ‘behave like Angela Merkel’ or (sich) rausmerkeln:

(45) | “In dem Sinne hätte Angela Merkel sich aus der Frage, ob sie Feministin ist, auch nicht so rausmerkeln müssen” (Spiegel Online, 02.05.2017, http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/gesellschaft/ivanka-trump-und-ihr-verdrehtes-bild-vom-feminismus-kolumne-a-1145655.html) |

[In that sense, there was no need for Angela Merkel to merkel herself out of that question.] |

The same pattern can be found with schrödern and schröderisieren. While the latter is transitive, the first verb can be used in a headline like Merkel schrödert (‘Merkel acts like Gerhard Schröder’) (Die Zeit, 6.12.2012, http://www.zeit.de/2012/50/Merkel-Ruestungsexporte-Sicherheitspolitik). With respect to such verbs, Wengeler (2010: 86) distinguishes between mostly intransitive verbs of comparison, formed by conversion, and the mostly transitive verbs in -isieren expressing a transition.

Another example is steinmeiern (‘act like Frank-Walter Steinmeier’):

(46) | “Vizekanzler Gabriel inszeniert sich seit der Bundestagswahl als Verantwortungspolitiker, er versucht gewissermaßen zu steinmeiern.” (Die Welt, 09.02.2015, https://www.welt.de/print/welt_kompakt/debatte/article137251198/Gabriel-zeigt-Nerven.html) [Since the election, vice-chancellor Gabriel sets himself in scene as responsible politician, in a way, he tries to steinmeier.] |

Again, this is an intransitive verb, as opposed to transitive steinmeierisieren and Steinmeierisierung:

(47) | ‘Das Regieren in Konsens und mit Kommissionen, “die Steinmeierisierung der Politik kann nicht das letzte Wort bleiben”.’ |

(Die Welt, 22.11.2002, https://www.welt.de/print-welt/article268581/Schelte-fuer-Schroeder.html) [To govern in consensus and with commissions, “the Steinmeier-ization of politics cannot be the last word”.] |

The verb riestern (from former minister Walter Riester) through metonymical extension even became a technical term for paying into a certain kind of pension insurance (the Riester-Rente ‘Riester insurance’).

As Wengeler (2010: 93) pointed out, such new formations demonstrate the importance of shared knowledge. Shared knowledge about the world is necessary for every communication, but its importance has to be stressed for the proper interpretation of new and often ad hoc formations with low frequency.

3.6 Prefixation

Verbs in -isieren and the corresponding nouns in -isierung convey the transition from one state into another. A transition into the opposite direction, back to the original state, can be expressed as well by using prefixes (de-, ent-). And with the prefix re- a repetition of the transitional process can be put into words:

(48) | de-: |

dezentralisieren ‘decentralize’ – Dezentralisierung ‘decentralization’ | |

dekolonisieren ‘decolonize’ – Dekolonisierung ‘decolonization’ | |

ent-: | |

entmilitarisieren ‘demilitarize’ – Entmilitarisierung ‘demilitarization’ | |

entpolitisieren ‘depoliticize’ – Entpolitisierung ‘depoliticization’ | |

re-: | |

rekontextualisieren ‘recontextualize’ – Rekontextualisierung ‘recontextualization’ | |

revitalisieren ‘revitalize’ – Revitalisierung ‘revitalization’ |

While the prefix ent- can be used productively in German with all kinds of verbs (enterben ‘to dispossess’, entsagen ‘to abjure’, entschädigen ‘to compensate’, entmilitarisieren ‘demilitarize’), the use of de- and re- is much more restricted to foreign base words, which – in the verbal domain – means: verbs in -ieren. Nouns in -ung can be derived from all of these verbs (Enterbung, Entsagung, Entschädigung, Entmilitarisierung).

The productive use of de- and re- could again be accounted for by schema unification. Here is the schematic representation for the combination of de- and -isieren:

(49) | [X -isier]V + [de- V]V → [de- [X -isier]V]V |

The resulting schema is paradigmatically related to the corresponding nouns in -ung and to other complex words: dezentralisieren, Dezentralisierung, dezentralisierbar, Dezentralisierbarkeit.

4 Conclusion

In this paper, I have used the verbal suffix -ier and its variants in German to illustrate some of the questions related to the study of foreign word-formation. I have tried to show that an output-oriented and exemplar-based approach to morphology is necessary for a proper analysis of the phenomena in this domain of word-formation.

Foreign word-formation often shows a lot of irregularities and peculiarities that can only be fully understood when we take the historical genesis into account. Nevertheless, we do find regularity and patterns that language users seem to make use of. Schemas in Construction Morphology have an output-oriented orientation, and they can express the generalizations and abstractions that language users need in order to understand and use complex words and word-formation patterns. Language users do not need a complete decomposition of morphologically complex words into morphemes. The interpretation of complex foreign words takes place by means of paradigmatic association with similar words, rather than by decomposition. We use similarities with other complex words, paradigmatic relations and analogical reasoning to grasp the meaning of these words.Footnote 10

The German verbs in -ier(en) are formally related through the element -ier and its extended forms -isier or -ifizier. The category of the base element (a noun, an adjective or a root element, a confix) is less important than the fact that it returns in other complex words. For instance, we do not need to know the meaning of the root polem- in polemisieren ‘to polem(ic)ize’ in order to understand the meaning of this verb. It is linked to and motivated by other complex words like Polemik and polemisch. Through the comparison of these words and other words in -isieren, -ik and -isch, we know enough about the internal structure of these verbs to come to an adequate interpretation. We can use this information for the formation of new words.

The schema approach allows to specify subschemas that are characterized by formal and/or semantic features. Such subschemas can also be used to account for the productivity within a ‘semantic niche’ (cf. Hüning 2009). With respect to -isier(en) we find such a productive pattern for example for verbs that are based on person names (merkelisieren etc.). The case study has shown some of the relevant paradigmatic relations of such verbs (especially with the even more productive nouns in -isierung). It also demonstrated the importance of the old insight of Aronoff (1976: 45) that “productivity goes hand in hand with semantic coherence”. Semantic coherence together with a coherent syntactic behavior of the verbs (transitivity) turns out to be more important than formal characteristics of the bases. This does, however, leave room for creative use: everything is possible in the formation of new words, as long as it makes sense in a certain context (cf. Heringer 1984).

Furthermore, the formation of -ier(en) verbs has demonstrated the relevance of the notion of ‘schema unification’, used in Construction Morphology in order to account for the conflation of two word-formation processes in the formation of a new word. In the formation of a word like Deemotionalisierung ‘de-emotionalization’, the use of the prefix de- and the suffix -ung depend on the presence of the verbalizing element -isier. The corresponding verb does not need to be realized; for the formation of the complex noun it is sufficient that it could be formed if needed. Such interdependencies can be formalized very well as unification of schemas.

Another notion of Construction Morphology appeared to be necessary as well, the notion of ‘second order schema’, which can be used to analyze and motivate paradigmatic relations between morphologically complex words. For example, the structure of and the relation between dissimilieren and Dissimilation can be easily analyzed by means of a second order schema.

In this article, I largely neglected the historical perspective on complex loan words. I am, however, convinced that the Construction Morphology approach is very appropriate to express the following basic insight, formulated more than a century ago by Hermann Paul:

Es werden immer nur ganze Wörter entlehnt, niemals Ableitungs- und Flexionssuffixe. Wird aber eine grössere Anzahl von Wörtern entlehnt, die das gleiche Suffix enthalten, so schliessen sich dieselben ebensogut zu einer Gruppe zusammen wie einheimische Wörter mit dem gleichen Suffix, und eine solche Gruppe kann dann auch produktiv werden. Es kann sich das so aufgenommene Suffix durch analogische Neubildung mit einheimischem Sprachgut verknüpfen. (Paul 1920: 399)Footnote 11

I also did not consider the comparative perspective. The German verbs in -ier(en) have counterparts in other Germanic languages as well as in Romance languages. Closely related is Dutch, and many of the questions, the analyses and the insights presented here could be applied to this language as well. An interesting case is Luxembourgish. In Luxembourgish, the suffix has the form -éieren and it seems to be used productively.Footnote 12

A careful comparative analysis might shed some light on the factors that lead to divergence and convergence between languages. It would, for example, show that the emergence of productive word-formation patterns cannot only be observed for German, but for Dutch, English and other Germanic languages, as well. German Merkelisierung corresponds to Merkelization in English and to merkelisering in Dutch. What are the similarities, which language specific differences can be observed? It is an intriguing question which factors control the Europeanization or even internationalization of the lexicon. The emergence of parallel word-formation patterns through language contact and due to convergent communication needs is a phenomenon that deserves further investigation.

Notes

- 1.

In German the prefix ge- is omitted in participles from verbs with an unstressed first syllable (Duden 2005: 447).

- 2.

Cf. the etymological information available via DWDS (‘Das Wortauskunftssystem zur deutschen Sprache in Geschichte und Gegenwart’, www.dwds.de).

- 3.

But see Fleischer and Barz (2012: 432/3), who distinguish ten different ‘Wortbildungsreihen’, i.e. semantic patterns which they also find with other kinds of verbal word-formation.

- 4.

Interpreter can be found, but only as a loanword from English computer terminology.

- 5.

In Dutch we find a similar phenomenon with respect to loans from English. For some words, the Flemish use the suffix -eer to integrate the word into the verbal system, where Northern Dutch uses conversion and the infinitive marker -en: boycotteren, recycleren, handicapperen, relaxeren vs. boycotten, recyclen, handicappen, relaxen (Berteloot and van der Sijs 2002).

- 6.

Cf. Booij (2002: 176–182) for a discussion of stem allomorphy in Dutch.

- 7.

See e.g. the OED (-fy, suffix) for some historical notes (http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/75882).

- 8.

Fleischer (1997: 82), on the other hand, acknowledges the productivity of the pattern, but he wants to assume the (implicit) intermediate step of verb-formation. He criticizes Wilss for assigning suffix-status to -isierung.

- 9.

See for the combination of a prefix with -ung the contribution by Kempf and Hartmann (2018).

- 10.

This is in line with recent publications by Geert Booij, but see also Bybee’s (2010) plea for usage-based approaches or the discussion of ‘Bausteine und Schemata’ (building blocks and schemas) by Hartmann (2014: 186), who considers the advantages of a constructional schema approach to (productive) word formation patterns.

- 11.

English translation of the 2nd edition of Pauls Principles by H.A. Strong: “Words are always borrowed in their entirety; never derivative and inflexional suffixes. If, however, a large number of words containing the same suffix is borrowed, these range themselves into a group just as easily as native words with the same suffix: and such a group may become productive in its turn. The suffix thus adopted may be attached, by means of analogical new-creation, to a native root.”

- 12.

Peter Gilles pointed me to Southworth (1954) which might serve as a starting point for investigating the use of the pattern in Luxembourgish.

References

Ammon, U, H. Bickel, and A.N. Lenz, eds. 2016. Variantenwörterbuch des Deutschen. Die Standardsprache in Österreich, der Schweiz, Deutschland, Liechtenstein, Luxemburg, Ostbelgien und Südtirol sowie Rumänien, Namibia und Mennonitensiedlungen. 2., völlig neu bearbeitete und erweiterte Auflage. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.

Aronoff, M. 1976. Word formation in generative grammar. Linguistic Inquiry Monographs 1. Cambridge, MA/London: The MIT Press.

Bauer, L. 1998. Is there a class of neoclassical compounds, and if so is it productive? Linguistics 36 (3): 403–422.

Beckner, C., R. Blythe, J. Bybee, M.C. Christiansen, W. Croft, N.C. Ellis, J. Holland, J. Ke, D. Larsen-Freeman, and T. Schoenemann. 2009. Language is a complex adaptive system: Position paper. Language Learning 59 (Suppl. 1): 1–26.

Berteloot, A., and N. Van der Sijs. 2002. Dutch. In English in Europe, ed. M. Görlach, 37–56. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Bloomfield, L. 1933. Language. New York: Holt.

Booij, G. 2002. The morphology of Dutch. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2010. Construction morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2015. Word-formation in construction grammar. In Word-formation. An international handbook of the languages of Europe, ed. P.O. Müller, I. Ohnheiser, S. Olsen, and F. Rainer, Vol. 1, 188–202. (HSK – Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft 40.1). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

———. 2016. Dutch. In Word-formation. An international handbook of the languages of Europe, ed. P.O. Müller, I. Ohnheiser, S. Olsen, and F. Rainer, Vol. 4, 2427–2451. (HSK – Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft 40.4). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

———. 2017. The construction of words. In The Cambridge handbook of cognitive linguistics, ed. B. Dancygier, 229–246. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Booij, G., and J. Audring. 2018. Partial motivation, multiple motivation: the role of output schemas in morphology. This volume.

Bybee, J. 1988. Morphology as lexical organization. In Theoretical morphology, ed. M. Hammond and M. Noonan, 119–141. San Diego: Academic.

———. 2010. Language, usage and cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Demske, U. 2000. Zur Geschichte der ung-Nominalisierung im Deutschen: Ein Wandel morphologischer Produktivität. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Deutschen Sprache und Literatur 122 (3): 365–411.

Donalies, E. 2009. Stiefliches Geofaszintainment – Über Konfixtheorien. In Studien zur Fremdwortbildung, ed. P.R.O. Müller, 41–64. (Germanistische Linguistik 197–198). Hildesheim/Zürich/New York: Georg Olms Verlag.

Duden. 2005. Duden. Die Grammatik, 7, völlig neu erarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage. Herausgegeben von der Dudenredaktion. (Duden 4). Mannheim/Leipzig/Wien/Zürich: Dudenverlag.

Eins, W. 2008. Muster und Konstituenten der Lehnwortbildung. Das Konfix-Konzept und seine Grenzen. (Germanistische Linguistik Monographien 23). Hildesheim/Zürich/New York: Georg Olms Verlag.

Eisenberg, P. 2012. Das Fremdwort im Deutschen. 2., überarbeitete Auflage. (De Gruyter Studium). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.

Elsen, H. 2011. Grundzüge der Morphologie des Deutschen. (De Gruyter Studium). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.

Fleischer, W. 1997. Zum Status des Fremdelements -ier- in der Wortbildung der deutschen Gegenwartssprache. In Sprachsystem - Text - Stil. Festschrift für Georg Michel und Günter Starke zum 70. Geburtstag, ed. Ch. Keßler, and K-E. Sommerfeldt, 75–87. (Sprache – System und Tätigkeit 20). Frankfurt am Main/Berlin/Bern/New York/Paris/Wien: Peter Lang.

Fleischer, W., and I. Barz. 2012. Wortbildung der deutschen Gegenwartssprache, 4. Auflage; völlig neu bearbeitet von Irmhild Barz unter Mitarbeit von Marianne Schröder. (De Gruyter Studium). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Fuhrhop, N. 1998. Grenzfälle morphologischer Einheiten. (Studien zur deutschen Grammatik 57). Tübingen: Stauffenburg Verlag.

Goldberg, A.E. 2003. Constructions: A new theoretical approach to language. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 7 (5): 219–224.

Grimm, J. 1864. Über das Pedantische in der deutschen Sprache. Vorgelesen in der öffentlichen Sitzung der Akademie der Wissenschaften am 21. October 1847. In Reden und Abhandlungen von Jacob Grimm, ed. K. Müllenhoff, 327–373. (Kleinere Schriften von Jacob Grimm 1). Berlin: Ferd. Dümmlers Verlagsbuchhandlung.

Hartmann, S. 2014. Wortbildungswandel im Spiegel der Sprachtheorie: Paradigmen, Konzepte, Methoden. In Paradigmen der aktuellen Sprachgeschichtsforschung, ed. V. Ágel, and A. Gardt, 176–193. (Jahrbuch für Germanistische Sprachgeschichte 5). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.

Henzen, W. 1965. Deutsche Wortbildung. Dritte, durchgesehene und ergänzte Auflage. (Sammlung kurzer Grammatiken germanischer Dialekte). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Heringer, H.J. 1984. Gebt endlich die Wortbildung frei! Sprache und Literatur in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 15: 42–53.

Hüning, M. 1999. Woordensmederij. De geschiedenis van het suffix -erij. (LOT International Series 19). Den Haag: Holland Academic Graphics.

———. 2009. Semantic niches and analogy in word formation: Evidence from contrastive linguistics. Languages in Contrast 9 (2): 183–201.

Kempf, L., and S. Hartmann. 2018. Schema unification and morphological productivity: A diachronic perspective. This volume.

Koskensalo, A. 1986. Syntaktische und semantische Strukturen der von deutschen Basiswörtern abgeleiteten -ieren-Verben in der Standardsprache. Zeitschrift für germanistische Linguistik 14 (2): 175–191.

Kühnhold, I., and H. Wellmann. 1973. Deutsche Wortbildung – Typen und Tendenzen in der Gegenwartssprache. Erster Hauptteil: Das Verb. (Sprache der Gegenwart 29). Düsseldorf: Pädagogischer Verlag Schwann.

Leipold, A. 2006. Verbableitung im Mittelhochdeutschen: eine synchron-funktionale Analyse der Motivationsbeziehungen suffixaler Verbwortbildungen. (Studien zur mittelhochdeutschen Grammatik 2). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Lüdeling, A., T. Schmid, and S. Kiokpasoglou. 2002. Neoclassical word formation in German. In Yearbook of morphology 2001, ed. G. Booij and J. Van Marle, 253–283. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Marchand, H. 1969. Die Ableitung deadjektivischer Verben im Deutschen, Englischen und Französischen. Indogermanische Forschungen 74: 155–173.

Müller, P.O. 2000. Deutsche Fremdwortbildung. Probleme der Analyse und der Kategorisierung. In Wortschatz und Orthographie in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Festschrift für Horst Haider Munske zum 65. Geburtstag, ed. M. Habermann, P.O. Müller, and B. Naumann, 115–134. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Müller, Peter O., ed. 2005. Fremdwortbildung. Theorie und Praxis in Geschichte und Gegenwart. (Dokumentation Germanistischer Forschung 6). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Müller, P.O., ed. 2009. Studien zur Fremdwortbildung. (Germanistische Linguistik 197–198). Hildesheim/Zürich/New York: Georg Olms Verlag.

———. 2015. Foreign word-formation in German. In Word-formation. An international handbook of the languages of Europe, ed. P. O. Müller, I. Ohnheiser, S. Olsen, and F. Rainer, Vol. 3, 1615–1637. (HSK – Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikations-wissenschaft 40.3). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

Öhmann, E. 1970. Suffixstudien VI: Das deutsche Verbalsuffix -ieren. Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 71 (3): 337–357.

Paul, H. 1920. Prinzipien der Sprachgeschichte: Studienausgabe. 9., unveränderte Auflage, 1975 [Nachdruck der 5. Auflage, 1920]. (Konzepte der Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaft 6). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Rosenqvist, A. 1934. Das Verbalsuffix -(i)eren. Suomalaisen Tiedeakatemian Toimituksia. Annales Akademiae Scientiarum Fennicae. Sarja-Ser B, Nide-Tom. XXX, 589–635.

Scherer, C. n.d. Zur Geschichte des -ieren-Suffixes im Deutschen. Manuskript. Mainz, ms.

Schlücker, B. 2017. Eigennamenkomposita im Deutschen. In Namengrammatik, ed. J. Helmbrecht, D. Nübling, and B. Schlücker, 59–93. Linguistische Berichte, Sonderheft 23.

Seiffert, A. 2009. Inform-ieren, Informat-ion, Info-thek: Probleme der morphologischen Analyse fremder Wortbildungen im Deutschen. In Studien zur Fremdwortbildung, ed. P. O. Müller, 19–40. (Germanistische Linguistik 197–198). Hildesheim/Zürich/New York: Georg Olms Verlag.

Southworth, F.C. 1954. French elements in the vocabulary of the Luxemburg dialect. Bulletin linguistique et ethnologique 2: 1–20.

Van Marle, J. 1985. On the paradigmatic dimension of morphological creativity. (Publications in language sciences 18). Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

Wengeler, M. 2010. Schäubleweise, Schröderisierung und riestern. Formen und Funktionen von Ableitungen aus Personenamen im öffentlichen Sprachgebrauch. Komparatistik online 2010, 79–98.

Wilmanns, W. 1899. Deutsche Grammatik. Gotisch, Alt-, Mittel- und Neuhochdeutsch. Zweite Abteilung: Wortbildung. Zweite Auflage. Strassburg: Karl J. Trübner.

Wilss, W. 1992. Schematheorie und Wortbildung. Deutsch als Fremdsprache 29 (4): 230–234.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information