Abstract

This chapter analyses the transformation of the map of two pro-refugee social movement organisations in Istanbul in that period, namely, the Migrant Solidarity Network and Mülteciyim Hemşerim! through an analysis of their frames, repertoires of action, organisational structures, and their composition. The research is based upon a dozen of in-depth interviews conducted with pro-refugee activists and ethnographically inspired participant observation. The chapter employs ‘refugeehood’ as a useful category to understand how the precarious political space in Turkey defined the outlook of the pro-refugee social movement map of the city, by transforming empathy towards refugees into identification with them.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the Syrian war in early 2011, Turkey has become one of the most popular departure points for Syrians who were forced to migrate—due not only to the relatively easy access to the border but also to the so-called open door policy practised by the Turkish authorities across the border. Until mid-2016, copious numbers of migrants entered the country and either stayed, or found ways to reach one of the Greek islands after a long and risky journey—although many perished. While the varying sentiments and reactions created by the movement of millions of migrants into Europe are well known, the story of Turkey and other non-European countries that in fact host larger migrant populations remained marginal.

In this chapter, I will analyse how the so-called refugee crisis , or the long summer of migration, affected pro-refugee activism in Istanbul . I will try not to overgeneralise my commentaries to the whole country, as thorough research on pro-refugee civic movements in Turkey, or even in Istanbul, requires longer and more detailed and comparative field research.

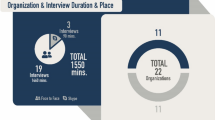

My arguments in this chapter are based on structured in-depth and non-structured interviews with a dozen activists and on my field observations in Istanbul over a five-month period from September 2016 to January 2017. Despite the relative openness of my interviewees, working on civic movements that support refugees in Turkey proved to be a challenge—not only due to the complexity of the pro-refugee movement map but also because of recent political developments in the country. The limitation of political space and suppression of all sorts of political activism after the June 2015 elections constantly intensified. The state of emergency declared after the coup attempt of 15 July 2016 has made access to activists in the field even more difficult. Under the state of emergency rule, even interviews with activists who clearly had a political agenda different from that of the government could easily become a document for further political criminalisation. Since the declaration of the state of emergency, (I)NGOs are under threat of being shut down by the government, and activists risk being criminalised from one day to the next (Heller 2017).

This is where the theoretical backbone of this chapter becomes a reality: as scholars of political opportunity structure have traditionally argued, political opportunities, meaning ‘consistent but not necessarily formal, permanent, or national signals to social or political actors which either encourage or discourage them to use their internal resources to form social movements ’ (Tarrow 1996, p. 54), defined the possibilities for challenging groups to mobilise effectively (Goodwin and Jasper 2004). Under the conditions imposed by the state of emergency in Turkey , which can be defined as the disappearance of formal institutional structure in favour of informal procedures and strategies (Jenkins and Klandermans 1995), political opportunities were closed down, hindering political mobilisation, and those involved with unrecognised activism were ‘criminalised’.

However, as critics of the literature on political opportunity structure suggest, opportunities are not homogenous, nor are activists devoid of agency. Activists and social movements , even under authoritarian regimes, have space for manoeuvre in positioning themselves vis-à-vis the regime and other challengers. In other words, in the determination of the degree and scale of mobilisation, ‘what matters is not only the extent to which social movements face an open or closed institutional setting, but also the extent to which their claims and identities relate to prevailing discourses in the public domain’ (Giugni 2009, p. 364). Discursive opportunities allow activists to employ strategies within an institutional cultural context, even under highly limited political space. Furthermore, these discursive opportunities always have the potential to transform into ‘specific opportunities’, giving more agency to the activists in challenging specific characteristics of the existing regime. As Koopmans et al. (2005) argued, ‘the specific opportunities for claim-making in the field of immigration and ethnic relations politics stem from the prevailing conceptions of citizenship and their crystallization in incorporation regimes’. Therefore, the cases here demonstrate that the relevance of discourses around refugeehood not only provided ‘discursive opportunities’, as they replaced previous discourses around identity formation and citizenship, but also related to specific opportunities, particularly around sociopolitical and economic status shared with the refugees.

Furthermore, I argue here for a more dialectic understanding of political power and structures. Indeed, the increasing repression of the Turkish state especially in the post-15 July period negatively affected opportunity structures. However, at the same time, it strengthened the bonds of solidarity among activists, triggering further mobilisation. As della Porta and Kriesi (1999) suggest, with globalisation, the inclusion of actors beyond national borders complicates how political structures affect social movements. Different movement organisations interact within these political institutions and with each other in a transnational space, within a heterogeneous ‘relational field’ (Goldstone 2004).

In this article, I argue that the complexity of the political opportunity structure affected pro-refugee social movement organisations in Istanbul. From the onset of the Syrian civil war until early 2017, short-term changes in the capacity and extent of democracy in Turkey affected political opportunities . In the first period, from 2011 to mid-2013—at a time when the refugee flow had not yet become a public concern—Turkish political structures were challenged through a wave of large-scale street protests, mass hunger strikes in prisons, and critical discourses in various public spaces. In the second period, from mid-2013 until late 2015—during which most refugees entered the country—the political space in the country opened up, mostly thanks to the ceasefire between the Turkish army and the Kurdish guerrilla movement (PKK) and the feeling of empowerment fuelled by the Gezi protests . The third period, from late 2015 to early 2017, saw instead the closing down of the political space and the crushing of contentious politics led mostly by the Kurdish political movement. The state of emergency declared right after the attempted coup d’état on 15 July 2016 criminalised all political contention and allowed the government to repress political opposition. Focusing on the last period, however, I argue here that the political opportunity structures in the country were not the only determinant for the conceiving of new forms of claim making and mobilisation. In the coming sections, I argue that the pro-refugee movement organisations in Istanbul challenged the existing refugee regime and that they tried to employ transgressive contention strategies in spite of increasing political oppression. This was made possible through the framing of contention within a shared experience of refugeehood .

Framing Contention: Refugees and/or Refugeehood?

One issue to tackle when talking about ‘refugees ’ in Turkey is who the refugee really is in the Turkish context—a question also addressed within the pro-refugee movements . Due to the geographical limitations put on the Geneva Convention of 1951 and the 1967 protocol by the Turkish authorities, full refugee status can only be granted to asylum seekers coming from European countries. Therefore, in its history, Turkey had granted refugee status to only around 60 people. The ambiguity of the category creates not only legal issues for the movements but also an issue of scale. Many pro-refugee movement organisations, and especially NGOs working in the field, define their activities in a larger framework of migration, some focusing on forced migration . That ambiguity was further complicated in 2013 with the granting of special protection status to migrants coming from Syria (Kutlu 2015). The majority of the movements working for forced migrants/refugees since the 1980s, including those under scrutiny here, had to negotiate with the Turkish government to withdraw the geographical limitations and extend the ability to apply for refugee status to all asylum seekers regardless of their country of origin.

Beyond the legal context, the spatial distribution of migrants plays a key role in defining who the refugee is. Due to the lack of a coherent and applicable migration/refugee policy in the country, the state’s initial plan to keep migrants within the confines of state-sponsored refugee camps failed. Although most of the Syrian migrants who crossed the border were settled in refugee camps in the first years of the crisis, the unfavourable conditions there resulted in the passage of refugees to urban centres in search of better accommodations, jobs, and educational opportunities. The concentration of around 400,000 (Fig. 2.1) refugees in certain neighbourhoods of the city that hosted mostly urban underclasses and working classes altered the functioning of these neighbourhoods and blurred the line between refugees and locals.

Distribution of refugees in ten cities (02.02.2017—Source: Ministry of Interior—Directorate General of Migration Management website—www.goc.gov.tr)

The question of who the refugee is becomes all the more relevant given the relatively long history of refugee flows into the country (the 1980s experienced at least two major waves—from Iraq and Bulgaria) (Kirişçi and Ferris 2015). In addition, the internally forced migrations of a considerable number of Kurds since the 1990s from Turkish Kurdistan into the urban centres in the West of the country essentially made internally displaced Kurds into refugees. Against this background, the pro-refugee movement organisations under scrutiny here frame their field of contention more around ‘refugeehood’ than around a refugee status defined in legal terms. Refugeehood is understood here as ‘the loss of an entire social texture into which [the rightless] is born and in which they established for themselves a distinct place in the world’ (Arendt 2001, p. 267). Although many social theorists developed a concept of refugee equal to the ‘scum of the earth’ (see Owens 2009; Bradley 2014), refugeehood in the Istanbul context is not downgraded to mere powerlessness, to silence, or to a ‘bare life’ (Agamben 1999). Rather, it refers to a new political state through which political subjects that are otherwise separate social units (Rellstab and Schlote 2015) interconnect and renegotiate the conditions of citizenship, identity building, the right to have rights, and the relationship between state institutions and citizens.

The pro-refugee grassroots activist scene in Istanbul represents a shared political space in which refugeehood has become a unifying category, displaced and local alike. Instead of thinking of the refugee as a legal category, the activists in Istanbul identified themselves with the refugees (Ataç et al. 2016). The state of refugeehood has in the process become a reliable frame for building a movement identity and political contention under the political structures in Turkey . More specifically, the contentious politics of citizenship and identity formation that was long dominated by the Kurdish political movement is reallocated within the contention triggered by the politics of refugeehood.

The struggle for democratisation and extended citizenship rights was framed within the Kurdish movement between 2011 and 2015. In other words, the contentious politics of citizenship was ‘Kurdified’. However, in the period under scrutiny here, a distinct identity and form of resistance through identification with the refugees was born. In addition to the impossibility of finding another ‘distinct place in the world’, the amount of rightlessness —or to put it differently, ‘illegality’—defined through the state of refugeehood that the pro-refugee activists in Istanbul shared with refugees challenged notions of nation-state, citizenship, borders, free movement, and globalisation at the same time. In the short fieldwork period, I witnessed the emergence of a new political space whereby new political subjects were born, negotiating ‘citizenship in motion’ (Mezzadra 2004). The activists suggest that they framed their activism within a space defined by motion, precarity, instability, but at the same time political resistance and contention—in other words, refugeehood as political struggle (Ataç et al. 2016).

Despite the ambiguities of the legal category of refugee and the focus on a state of refugeehood on the activists’ side, it is a fact that ‘refugee’ as a concept has become much more widely used—part of the daily language of common Istanbulites and the citizens of Turkey—as the numbers of Syrian migrants increased dramatically (Fig. 2.1). The flow of refugees into Turkey started in September 2011. The relatively less intense state of the war lasted for around a year, triggering an influx of Syrian refugees into Turkish territories. As the Turkish government employed an ‘open door’ policy regarding the Syrian refugees, their numbers grew in a short period, from around 14,000 in 2012 to 1,500,000 at the end of 2013 (see Fig. 2.2). The intensification of the war in Syria—especially the massacres of Kurdish and Ezidi populations by ISIS—and the siege of Kobane in late 2014 created the main push for the influx of more than two million refugees into Turkish territories between 2013 and 2015.

Syrians under ‘temporary protection’ (02.02.2017—Source: Ministry of Interior—Directorate General of Migration Management website—www.goc.gov.tr)

The negotiations between the EU and Turkey started around late August 2015, eventually resulting in a refugee ‘deal’ aimed at preventing the flow of refugees into Europe, marking a period of change limiting and regulating the entry of Syrians into Turkey and their movement in and out of the country. During this period, sympathy towards the refugees peaked. After the approval of the ‘deal’ in March 2016, the dramatic increase in the numbers of refugees into the country came to a halt. This period (from mid-2015 to early 2016)—referred to as ‘the long summer of migration’ by the pro-refugee groups in Turkey—has become a milestone in the shaping of public opinion for and against the refugees, like their counterparts in Europe.

For or Against Refugees/Migrants?

Despite the ‘welcoming’ approach of the government in Turkey, the social reaction to the influx of migrants into the country was not homogenous. Nearly all my interviewees stated that the hundreds of refugees, who at times changed the ethnic and class composition of a whole neighbourhood, were not initially welcomed. Especially in certain neighbourhoods of Istanbul, the refugees were suspiciously contained. True, collective anti-refugee sentiments did not rise; but conflicts were widespread, moved by concerns for employment and by ethnic stereotypes (Kutlu 2015). According to a ‘Refugees Welcome Index’ compiled by Amnesty International, Turkish society was among the six least welcoming.Footnote 1

Although discrimination and physical violence against Syrian migrants —especially in urban centres—are rarely highlighted in the media, xenophobia and anti-refugee sentiments have taken place publicly in discursive forms. Analyses of newspapers and other media prior to the ‘refugee crisis ’ found language that was pejorative and based on depictions of refugees as sources of threat, criminality, economic burden, and sexual abuse. This language was commonly shared by the mainstream media (Yaylacı and Karakuş 2015). Furthermore, especially in its first phases, the refugee flow was considered by the mainstream media as a flow of jihadists (Hurriyet Daily News 2013). Besides the anti-refugee sentiments expressed on a more discursive level, an online platform that observed and mapped human rights violations against refugees in Turkey has demonstrated that it was not uncommon to find labour exploitation, physical assault, sexual abuse, and other kinds of human rights violations against refugees, especially in the smaller urban centres.Footnote 2 Furthermore, a few NGOs have also reported on the discriminatory discourses in the field (İHD 2013; MAZLUMDER 2015).

However, the complexity of the political antagonism that has developed since the June 2015 elections makes it harder to distinguish human rights violations against refugees from those against the internally displaced Kurds and citizens from other ethnic and religious backgrounds. Looking at the newspapers and reports of human rights supporters, one may conclude that the problems related to the refugees have in fact been related to the state of refugeehood. As a report published by Human Rights Association (İHD) suggests, discrimination against Kurds was not limited to those who had come from Syria (İHD 2013). Similarly, in a letter to Ban Ki-moon , General Secretary of the United Nations, Co-Chairs Selahattin Demirtaş and Filiz Kerestecioğlu of the pro-Kurdish People’s Democracy Party (HDP) stated that ‘millions of Kurdish citizens of Turkey and more than a million Syrian refugees are living […] under the conditions of conflict with chronic needs and constant fear’ (HDP 2016).Footnote 3

In this context, determining the activities, motivations, aims, and actors of pro-refugee movements becomes harder due to the fluidity of the political space within the almost yearlong period labelled as ‘refugee crisis ’ in Europe. Not only the increasing numbers of refugees but also the formation of public opinion through conventional media and new media channels resulted in the transformation of the activist scene in the country, especially in Istanbul. However, feelings of enmity and fear towards refugees transformed into sympathy and ‘neighbourship’ [komşuculuk] within a year of their settlement in various neighbourhoods (Interview TU4). While sharing similar quotidian concerns strengthened the bonds between the locals and the newcomers, religion (Islam) and ethnicity (in the case of the Kurds) seem to have played a further role (Kaya 2016). Beyond the cultural identification, sharing the same problems imposed by the state of refugeehood made it easier to join the struggle.

Despite the relatively sympathetic attitude towards refugees, not all such energy transformed into a movement organisation. A general glance at pro-refugee civic action in Istanbul suggests a complex and crowded map of social movement organisations and NGOs already existing prior to the long summer of migration—as well as new ones, although the actors usually remained isolated. Most of the NGOs and a few movement organisations were active in providing legal support to refugees in addition to psychosocial support, focusing on addressing immediate needs rather than actively challenging the existing migration regime. Most of these NGOs had weak ties with the formal national and transnational institutions and with each other—with the exception of İKGV, SGDD supported by UNHCR, and faith-based NGOs, which collaborated with the government offices (Kutlu 2015). These NGOs were already active before the ‘crisis’ and employed mostly contained contention (Tilly and Tarrow 2007).

Mobilising for Refugees in Istanbul: The Migrant Solidarity Network (MSN) and Mülteciyim Hemşerim!

The research conducted for this project focused on two main groups that were/are active in the network of solidarity initiatives with refugees. The relatively small number of groups under scrutiny is due to the difficulties in conducting structured interviews as a result of the closing down of the political space in Turkey, especially after the 15 July coup attempt and the following state of emergency, now in its second year. Not only the ‘fear’ of leaving a ‘record’ of one’s political history behind but also the idea of ‘betraying’ the cause by objectifying it as part of an academic study seems to play an important role in the hesitancy of potential interviewees.Footnote 4 The two groups chosen (the Migrant Solidarity Network [Göçmen Dayanışma Ağı] and Mülteciyim Hemşerim! Network Footnote 5) represent two different types of groups present in Istanbul. However, in comparison to the pre-crisis organisations, they both aimed at employing transgressive repertoires of contention (Tilly and Tarrow 2007).

Several movement organisations that had existed prior to the crisis are criticised by activists of the two organisations for failing to create opportunities for contentious politics, as they ‘lack the independent spirit’ and their actions were limited by the political agenda of the funding authorities (Interview TU2). The most important effect of the long summer of migration has been the emergence of the actors that first and foremost aimed at challenging the existing migration regime in Turkey. Indeed, the value of action changed from an NGO-oriented one towards a more social movement-oriented perspective, from containing contention to transgressive contention. Given the political opportunity structures in the country, humanitarian intervention was monopolised by the state and by hierarchically organised groups with close ties to the state/government. The scepticism towards NGOs with links to the Turkish state pushed activists towards more independent, grassroots organisations. An example of this emerged during a forum on 24 August 2016 in a park in the Beşiktaş district, with actual and potential refugee activists. Most of the 60 or more individual activists participating in the forum expressed their need to find accountable movement organisations, with transparent structures, easy access, and participatory structures.

This need was filled mainly by the two movement organisations under scrutiny here. Founded in 2006 to follow a trial related to the killing of Nigerian refugee Festus Okey while he was under arrest in Istanbul, the Migrant Solidarity Network was one of the oldest pro-immigrant/refugee groups, not only in Istanbul but in the whole country as well. The movement is defined by its members as once the centre of all migrant activism: whether pro-establishment, Islamist, or opposition, anyone who dealt with migration issues in Turkey knew of MSN. By the time of this research, the movement was undergoing changes. Mülteciyim Hemşerim! , on the other hand, was a product of the refugee crisis and founded in late 2015 by activists previously active in urban movements. Both movements are organised horizontally, with decisions taken in weekly meetings open to everyone.

Why Act? Motivations for Mobilisation

As mentioned, the political space in Turkey became highly polarised after the June 2015 elections. Pro-refugee movements within that space did not work in full co-operation with each other, and conflict and competition defined the network. While the increase in the number of refugees during the ‘long summer of migration’ forced new actors to enter the field, the polarisation of the political space in Turkey , the need to take sides quickly, and the non-existence of hybrid spaces affected the formation of the pro-refugee activist space too. Pro-refugee grassroots movements developed in an antagonistic fashion, competing for survival in a rather competitive field (Kutlu 2015).

The motivations for activists choosing to be outside of such professional groups and NGOs were various. However, activists from both movements expressed their beliefs regarding the importance of the values attached to freedom of movement and to the political ideal of a borderless world. The main turning point for most of my interviewees and the activists who shared their opinions with me in an unstructured form was the prohibition for the refugees to move from Turkey to Greece in September 2015. On 14 September 2015, about 3000 refugees started walking, mainly from Istanbul to the Pazarkule entry point at the border with Greece. After a four-day struggle with police forces, the refugees reached Edirne, the border city with Greece, on 19 September. However, Turkish security forces blocked their passage into Greece, and the refugees were contained in parks and stadiums in Edirne. The refugees rejected humanitarian aid provided by various state-sponsored charity organisations and demanded their safe passage into Greece. During this event, the act of walking had become a way to challenge and protest the system; the refugees/protestors therefore called themselves Abiroun la Aksar/Bare Walkers .

As one activist explained, he decided to join the so-called Bare Walkers (yalın yürüyenler) to the border between Turkey and Greece upon seeing the refugees stuck in the main coach station of Istanbul (Interview TU1). The motivation for his decision was first and foremost an emotional state. Others expressed similar narratives regarding their sudden decision to join the struggle for refugees (Interviews TU2, TU3, and TU4). Most of the activists who worked in the field had been involved with other forms of activism prior to the ‘long summer of migration’, but the scenes they encountered in various public spaces in Istanbul, and the stories they heard about refugees around the country, made them turn to the struggle for refugee rights.Footnote 6

Other narratives hint at the further role of such chance encounters to be recruited in one organisation or another (della Porta 2006, p. 202). One activist (active in almost all groups in the field, whose only motivation to stay in Turkey despite the ‘terrible’ political situation is to bring all the competing pro-refugee movement organisations together) explained that she became active in the pro-refugee mobilisation after encountering Kurdish refugees in the border zone with Syria. Others also explained their commitment as triggered by their physical encounters with refugees in various parts of the country. One activist mentioned that ‘seeing refugees and homeless people sleeping in front of train stations in the streets’ in Italy was a critical experience in his mobilisation (Interview TU1). Similarly, a primary school teacher of Kurdish origins became an activist in the Migrant Solidarity Network /Kitchen out of—partially political—curiosity. He happened to go to the kitchen in his neighbourhood ‘just to see what was going on there’. After that, he became one of the key activists of the Kitchen, known as a committed playmate for the refugee children.

Beyond the chance encounters, at a more strategic level, the activists shared the claim for a borderless world. However, the rising emotions towards refugees since late 2015 resulted in various contradictions in that regard. Although the majority of the movements in Istanbul criticise and campaign against the lack of a legal refugee status in the country, like the official ideology, they seem to consider Turkey as a country of transit, from which refugees were supposed to cross into Europe. In a comparative sense, this has become an important difference with pro-refugee movements in Spain, Germany, and Sweden that aimed at better integrating the refugee population into the society. Therefore, the pro-refugee mobilisation in Istanbul (and in Turkey to a certain extent) had a different motivation from many of the ‘welcome’ initiatives in Europe: namely, to facilitate the refugees’ safe passage into Europe and to help their refugee neighbours to survive until they could move elsewhere, while trying to force the Turkish state to accept all the points of the Geneva Convention .

However, and more importantly, pro-refugee mobilisation was not only related to the concrete problems of the refugees. The dynamics of Turkish politics prior to and during the refugee crisis has been equally influential in the direction of the mobilisation of activists. The closing down of the political space in Turkey after the 7 June elections in 2015, due to the escalating violence coming from ISIS and the Turkish state/army, has hindered the pace of mobilisation and the channels of participation in refugee politics in general. However, it has also created suitable grounds not only for the construction of alternative spaces in which the concrete needs of refugees are addressed but also for the creation of those that allowed for politics of refugeehood to be negotiated between the refugees and citizens. Activists have expressed their opinion on how their movement organisation (Mülteciyim Hemşerim!) attempted to join forces with their ‘fellow neighbours’ (i.e. refugees) to solve the problems they shared in the same neighbourhood. Therefore, the above-mentioned contradiction is overcome by integrating refugees or making them ‘comrades’ in an ongoing political struggle at the local level. In that sense, the border between activist and refugee is blurred. As one activist has noted:

Many activists within the pro-refugee movement consider themselves as refugees. Due to their precarious and uneasy place within the society, they want to flee; flee with the same passion and hope [as a refugee would]. Well, we have become refugees in our own country! (Interview TU1)

While his comment on ‘becoming refugees’ is used in a metaphorical sense, the total closing down of the political space in Turkey due to the attempted coup on 15 July 2016—and the following state of emergency that remains in place today—spatially confined the political opposition, limiting its members’ movements not only outside of the country but at times even more inside it. The limitations on movement from one city to another for political purposes anchored the activists to their own cities, and made it impossible even to imagine political protest or action in another city.Footnote 7 As an activist says, ‘the movement had to remain native to this place’ (Interview TU1).

Although the coup attempt on 15 July 2016 gave the Justice and Development Party (AKP) regime an excuse to suppress contentious movements and resulted in the closing down of the political space, the coup contradictorily gave activists motivation for further mobilisation too. For example, a group of about 20 people who defined themselves as active members of the Migrant Solidarity Network called for a forum on 24 August 2016 to gather all those who wanted to get involved with refugee activism, acting in solidarity thanks to the coup attempt. Although those 20 activists had gone as individuals to the No Border camp in Thessalonica in July 2016, the fear of not being able to return to Turkey because of the coup created stronger emotional bonds and solidarity between them. This feeling of solidarity within the groups expanded into broader solidarity with the refugees in Turkey once they returned. Thus, once again, the increasingly repressive and authoritarian political structures in Turkey played an indirect and dialectic role, hindering and fostering activism at the same time.

Therefore, the mobilisation of bottom-up initiatives in Istanbul was motivated by something that went beyond mere empathy towards refugees. The experience of refugeehood —of forcefully leaving one’s own country, or not being able to go back, or having one’s movements limited by force—seems to have played a crucial role in the establishment and strengthening of solidarity networks, in the way the contention is framed and repertoires of contention were set.

How to Act? Humanitarianism vs. Political Solidarity Action

An important characteristic of the pro-refugee activist field in Istanbul was the tension between humanitarian charity and political solidarity . This had already been a critical issue of conflict among the NGOs during the pre-crisis period. As the AMER (Association for Monitoring Equal Rights) representatives had complained in a forum, the aid groups and the NGOs working with or close to the government dominated the field and at times prevented the rights-oriented groups from actively participating in support work.Footnote 8 This was in line with the migration policies of the AKP regime , which employed a cultural discourse built around the religious bonds between the refugees and the Turkish state. As Gürhanlı suggests, the humanitarian aid discourse was ‘suggestive of the charity-based—rather than right-based—understanding of social support mechanisms that have come to define the social policies of the AKP regime ’ (Gürhanlı 2014). This split of the field has become a defining factor for the post-refugee crisis period . The cleavage between movement organisations that employed an Islamic discourse and those that took on a rather secular discourse towards the refugees was reflected in the conflict between humanitarian charity and political solidarity discourses. The separation is strengthened by the social and political fault lines imposed by the governing party in Turkey .

This dichotomy arises from the commercialised aspect of the humanitarian work. As one activist explains (Interview TU2), groups with humanitarian tendencies had to establish ties with professional organisations or corporations to find funding for their projects, and therefore lost the possibility of conducting independent work in the field. According to this interviewee, providing education, healthcare, and accommodation to refugees are the main objectives that defined this sphere of refugee support: he defines movements that focus on such issues as ‘movements of goodness, of conscience’. Notwithstanding his professional activism in Amnesty International , he criticised the NGOs and ‘humanitarian’ groups for overlooking the fact that the rights to education, healthcare, and accommodation are part of a larger human rights struggle and that this is where the disconnect between the refugees and the activists/volunteers takes shape.

The same discourse was shared by activists of the Migrant Solidarity Network , when discussing where the network positions itself within the map of pro-refugee movements. The network was defined as a non-humanitarian movement , aiming at politicising migration through the politics of refugeehood. While only a few groups in Istanbul focused on refugee issues that go beyond mere humanitarian aid—implicitly defined as satisfying the immediate needs of the refugees—the distinction between humanitarianism and political activity, or the reasons why humanitarian aid is not political, is never explained clearly by the activists.

The fact that humanitarian aid is viewed in a negative light within the two movement organisations is reflected in many of the internal discussions. In one internal meeting of the Migrant Solidarity Network in late September 2015, one activist explained his position in a discussion regarding registering refugee children in the public education system —the main focus of Mülteciyim Hemşerim! , which was openly against humanitarian aid—as he stated: ‘I don’t want to be involved with such charity work! Besides, why should refugee children be educated in a colonizing language like Turkish!?’

Although both groups under scrutiny have expressed similar and strong opinions regarding humanitarianism and charity, it is not very clear what makes them claim that their activism is more political than others. During the four-month period of observation, the Migrant Solidarity Network organised workshops on how to use new media in protecting the human rights of the refugees as well as internal discussions on how to mobilise local resources towards a transnational mobilisation against the EU-Turkey refugee deal —while Mülteciyim Hemşerim! focused on a local level, providing toys, education, and immediate necessities to the refugees residing in four neighbourhoods of Istanbul. It can be argued that the impossibility of organising street protests and public demonstrations, especially under the state of emergency, confined the political activism that these groups sought in their discourse but not in their practices. The Migrant Solidarity Network ’s attempts at organising street protests against the exploitation of migrant child labour by multinational textile companies in the city centre, and the initiative of the Mülteciyim Hemşerim! of organising a workshop/forum on the same subject, failed due to security concerns.

The few occasions on which the shared discourse of rights-based political activism was transformed into concrete action occurred in late November 2016, after a group of refugees started a fire in the infamous deportation centre in the Kumkapı district of Istanbul. Then, 123 migrants fled the centre thanks to the fire—20 of whom were later caught by the police. MSN issued an online statement against the deportation centres, emphasising their position against the EU-Turkey refugee deal that increased the criminalisation of migration and demanded the closure of the deportation centres.Footnote 9 Similarly, the forum against child labour by Mülteciyim Hemşerim! never took place—except in the form of a book that narrates the individual stories of children and adult refugee workers.Footnote 10

How to Act? ‘Touching’ the Refugees

Ayhan Kaya argues that the possibility of interacting with locals has discouraged Syrian refugees in Istanbul from leaving for Europe, as they feared that they would not be able to maintain a ‘cultural intimacy ’ there (Kaya 2016). This ‘cultural intimacy ’ was valued on the activists’ side as well, as they seem to have established ‘intimate’ connections with refugees from similar sociocultural backgrounds. Indeed, the issue of ‘disconnection’ from refugees formed yet another point of conflict and competition among the movement organisations. ‘Touching’ the refugees set the border between professional groups and grassroots, bottom-up initiatives. For some activists, work that ‘does not touch’ refugees is seen as less valuable in comparison to work that does.

The yalın yürüyenler [Bare Walkers] movement , which played a key role in the mobilisation of the movement organisations under scrutiny here, is defined by one activist as a critical moment that gave activists the opportunity to politicise refugeehood, as it allowed them to touch the refugees (Interview TU3). It was a moment that challenged the dominant conceptions of citizenship and national identities and borders. As another activist claimed, his choice of walking with refugees was first aimed at becoming part of the same experience, struggling together, and touching the refugees. In his view, a forum on the ongoing problems of refugees organised by activists and academics working in the field during the Bare Walkers’ protest proved useless. For him, these people did not intend to ‘touch’ the refugees. Therefore, he decided to act on his own and join the walk (Interview TU1). Later, in one of the internal meetings of the Migrant Solidarity Network , one activist who was formerly active in the network but did not join the meetings for a long time stressed that she was surprised by the fact that the network ‘does not touch’ the refugees anymore.

Emphasising the contact between activists and refugees is indicative of the way in which the actors located themselves vis-à-vis refugees and other activists. ‘Touching’ as an act of solidarity had a lot to do with the social class and space formation of the movements. Acting in contact with the refugees, or as an activist has put it ‘coming together with the refugees and doing something with them’ (TU4), cannot be possible without working in the local neighbourhoods that host mostly lower-class/underclass residents of the city. Therefore, the choice of location and scale for the movements is understood in relation to their class formation. In this context, the MSN was openly criticised by various neighbourhood groups for its ‘sterile’ politics and for employing an abstract and rather top-down politics. Composed of activists living in the middle-class neighbourhoods of the city, and others coming from various countries, the MSN plays the role of a transnational movement organisation in which activists can easily become part of cross-border solidarity initiatives thanks to the social capital provided by their social class.

In contrast, the Mülteciyim Hemşerim! activists stated that they had no ties abroad and no non-Turkish citizen activists; in fact, the majority of the most active members did not speak English or any other European languages. The transnational space in which the MSN positions itself was criticised by the latter as being alien to realities at the neighbourhood level. The hierarchy between the local and the transnational was therefore related not only to responding to the problems of the refugees but also to the general characteristics of alternative political space in Turkey.

Turkey Becomes Syria: Refugees and Turkish Politics—Activists and Syrian Politics

The juxtaposition of refugee issues with the domestic politics of Turkey is based on a long history and social memory around refugees and forced migrants that flowed into urban centres, especially throughout the late 1980s and 1990s. However, pro-refugee activists in Istanbul were confused as to the Syrian refugees’ position vis-à-vis Turkish politics. To put it differently, the political agency of refugees regarding Turkey’s domestic politics was ambivalent. Activists on the one hand wanted to see an ideal type of refugee that ‘struggles’ against injustices and inequalities with their fellow Turkish, Kurdish, Afghan, and Persian neighbours; on the other, they tended to treat the refugees as passive receivers without much political agency.

President Erdogan’s declaration prior to the coup attempt in July 2016 that the government had been working on a proposal to give citizenship to Syrians suggested that in general the role of refugees in Turkish politics was controversial. Erdogan’s declaration received a negative response even from among his supporters. The anti-refugee, xenophobic sentiments disappeared after the coup attempt on 15 July, and the discussion around what the status of refugees would be if they were to become Turkish citizens was put aside. However, the extent to and means through which Syrian refugees would participate in active political struggle in Turkey has remained an issue of debate in the movement organisations. The idea of including refugees in a ‘No’ campaign on the constitutional referendum on 16 April 2017, suggested by one of the most active members of the Migrant Solidarity Network , was criticised by another activist from the organisation as ‘objectifying’ refugees and putting their precarious state into an even more risky situation.

While the activists almost never mentioned Syrian politics as a determining factor in how the movement organisations are structured, debates around the reasons for the refugee flow and the war in Syria created conflicts among activists and movements at times. As an activist has suggested, one of the reasons that pro-refugee grassroots action in Turkey lost ground as of 2013 was the conflict within the Migrant Solidarity Network around the position of Assad in the civil war in Syria (Interview TU1). Those who viewed the Kobane resistance as a social revolution considered the civil war as ‘the Syrian revolution’. Although seemingly more complex, the perception of the politics in Syria caused a break-up within the Migrant Solidarity Network and led to the formation of the Migrant Solidarity Kitchen in the same year. The divide between the ‘Syrian revolution’ supporters and those with anti-war positions continues today.

Conclusion: Constituting a New Political Space?

What can be said after this brief overview of the pro-refugee activist scene in Istanbul based mostly on two social movements? As an interviewee stated:

I can say that the opposition movements in Turkey failed in supporting refugees and the refugee movement. Yet, we might need to read this keeping in mind the subjective conditions that the whole country is in. Opposition movements in Turkey have already been destroyed. That is a great obstacle for further mobilization. (Interview TU1)

One is tempted to take his argument as a fully satisfactory explanation. However, as I have tried to explain in this article, the political opportunity structure approach that he is hinting at does not suffice to grasp the story fully. The politics of pro-refugee mobilisation was not only determined by the numbers—as the flowering of pro-refugee grassroots movements does not coincide with the period of highest refugee flows—nor solely by the level of political repression. To the contrary, the period from mid-2013 to late 2015, which was characterised by an unprecedentedly high flow of refugees and low level of political pressure, saw less pro-refugee grassroots mobilisation than the period before and after. Starting in 2013, the map of pro-refugee movements was dominated by state-oriented NGOs and state institutions. It can be argued that the mobilisation of pro-refugee activists was instead related to the developments in domestic politics in Turkey and to the conceiving of new discursive opportunities. The period from 2013 to 2015 has been a relatively peaceful one thanks to the ceasefire between the Turkish army and the PKK. The particular focus of that period for activists was the destruction of ecologically sensitive zones in the country by the dam-building projects of the state and the Kurdish politics pioneered by HDP. Despite the dramatic increase in the number of refugees coming into the country and into Istanbul, neither the Gezi Park protests , nor the initiatives formed as a result, prioritised refugees.

The siege of Kobane at the end of 2014 and the consequent influx of predominantly Kurdish refugees into the country have not become the defining moments for the pro-refugee mobilisation either. The fact that new forms of claims making and contention developed especially during the second half of 2015 can be related to the delegitimisation of the Kurdish movement in Turkey following the break of the ceasefire with the PKK after the elections on 7 June 2015. The role of the HDP and Kurdish movement in general, in terms of deconstructing the existing citizenship regime, has been partially taken over by pro-refugee activism.

Pro-refugee activism allows to a certain extent for less antagonistic encounters with state and local governments, if not co-operation. Therefore, the transformation and reactivation of various pro-refugee groups in Istanbul since late 2015 are on the one hand related to the public visibility of refugees in the city, but on the other hand to the possibilities of channelling the energy arising out of the closing down of political opportunity structures, into a new discursive and political space. The need for both movements under scrutiny here to relocate themselves within that new space is representative of this trend. In this space, the politics of sympathy towards refugees transformed into identification with them, assimilating the refugees with the hosts in their state of refugeehood —and therefore employing specific opportunities. The need to ‘touch’ or establish cultural intimacy with the refugees or to reconstruct the refugee as a political subject was also part of the building up of a new political space: a space in which concepts of citizenship, nationality, and nation-states are renegotiated and challenged.

Interviews

-

TU1: Activist in the Migrant Solidarity Network. 28 September 2016, Istanbul.

-

TU2: Activist in Mülteciyim Hemşerim! 13 October 2016, Istanbul.

-

TU3: Activist in Mülteciyim Hemşerim! 13 October 2016, Istanbul.

-

TU4: Activist in Mülteciyim Hemşerim! 13 October 2016, Istanbul.

Notes

- 1.

Amnesty International 2016. The index was prepared with a mixed methodology and an unequal selection of samples. While interviewees were selected from educated classes with access at least to higher education in most cases, the sample from Turkey was chosen among groups of less-educated individuals over 15 years of age.

- 2.

Observatory for Human Rights and Forced Migrants in Turkey, www.ohrfmt.org

- 3.

- 4.

Members of the Migrant Solidarity Network openly stated their ‘allergy’ towards academics on various occasions.

- 5.

The name Mülteciyim Hemşerim! is almost untranslatable. The movement’s website translates it as the ‘Refugees, We Are, Neighbours’ Solidarity Network. The choice of such a vernacular name is not coincidental, as the movement’s emphasis on the ‘local’ plays a significant role.

- 6.

TU1 has been involved in activism since high school. He explains that before he joined the yalın yürüyenler and later became more active in refugee support, he was involved with environmental civic movements against the building of dams in various parts of the country. TU2 was an active member of Amnesty International’s branch in Van (a city near the border between Turkey and Armenia). Although his professional work there was to a certain extent related to migrant Kurds and Afghan refugees, his transition to full-time refugee activist was due to the developments in late 2015. TU3 and TU4 were involved with anti-urban transformation movements in Istanbul before becoming actively involved in pro-refugee action.

- 7.

The code of the state of emergency of 1983 and the statutory decrees issued during the state of emergency give the government and the mayors of each city the authority to prevent entry to or exit from any city. Although no example of prevention of pro-refugee activism exists, activists in other examples were prevented from entering cities and gathering in certain locations. For the example of Northern Forests’ Defence, see http://www.kuzeyormanlari.org/2016/08/07/kuzey-ormanlari-savunmasi-ohal-engeline-ragmen-safaalan-koyu-sakinleriyle-bulustu/

- 8.

See http://mavikalem.org/wp-content/uploads/Suriyeli-Mülteciler-Alanında-STÖler-Çalıştayı-Raporu_28.05.2014.pdf/, last accessed 31 July 2017.

- 9.

‘About the Kumkapı Migrant Riot’, http://gocmendayanisma.org/2016/11/20/kumkapi-gocmen-isyanina-dair/, last accessed 31 July 2017. Similar political action took place throughout 2016 and in the first months of 2017. For the statement signed not only by pro-refugee groups but also by a range of social movements from animal rights movements to children’s rights groups and LGBTI groups in May 2016, see ‘Do not Touch my Neighbour Press Statement’, http://gocmendayanisma.org/2016/05/23/komsuma-dokunma-basin-aciklamasi-do-not-touch-my-neighbour-press-statement/, last accessed 31 July 2017. Another statement in March 2017 sharing the same political discourse over freedom of movement was issued and signed by MSN and Mülteciyim Hemşerim!. See ‘Basına ve Kamuoyuna: #KOŞULSUZ HAREKET ÖZGÜRLÜĞÜ!’, https://multeciyimhemserim.org/2017/03/07/basina-ve-kamuoyuna-kosulsuz-hareket-ozgurlugu/, last accessed 31 July 2017.

- 10.

The report was part of the 2016 issue of the annual report of Adalet Arayana Destek Grubu [Support Group for Justice-Seekers], published since 2012. İş Cinayetleri Almanağı 2016, Istanbul, 2017.

References

Agamben, Giorgio. 1999. Homo Sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Trans. Heller-Roazen, Daniel. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Amnesty International. 2016. Refugees Welcome Survey 2016 – Views of Citizens Across 27 Countries, May. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/05/refugees-welcome-survey-results-2016/. Accessed 30 August 2017.

Arendt, Hannah. 2001. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt.

Ataç, Ilker, Kim Rygiel, and Maurice Stierl. 2016. Introduction: The Contentious Politics of Refugee and Migrant Protest and Solidarity Movements: Remaking Citizenship from the Margins. Citizenship Studies 20 (5): 527–544.

Bradley, Megan. 2014. Rethinking Refugeehood: Statelessness, Repatriation, and Refugee Agency. Review of International Studies 40 (1): 101–123.

della Porta, Donatella. 2006. Social Movements, Political Violence, and the State. In A Comparative Analysis of Italy and Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

della Porta, Donatella, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 1999. Social Movements in a Globalizing World. In Social Movements in a Globalizing World, ed. Donatella della Porta, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Dieter Rucht, 3–22. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Giugni, Marco. 2009. Political Opportunities: From Tilly to Tilly. Swiss Political Science Review 15 (2): 361–368.

Goldstone, Jack Andrew. 2004. More Social Movements or Fewer? Beyond Political Opportunity Structures to Relational Fields. Theory and Society 33 (3–4): 335–365.

Goodwin, Jeff, and James M. Jasper. 2004. Caught in a Winding, Snarling Vine: The Structural Bias of Political Process Theory. In Rethinking Social Movements, ed. Jeff Goodwin and James M. Jasper, 3–30. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Gürhanlı, Halil. 2014. The Syrian Refugees in Turkey Remain at the Mercy of the Turkish Government. The Turkey Analyst 7 (23). http://www.turkeyanalyst.org/publications/turkey-analyst-articles/item/364-the-syrian-refugees-in-turkey-remain-at-the-mercy-of-the-turkish-government.html. Accessed 30 August 2017.

HDP. 2016 Letter by HDP’s Co-Chairs to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon. https://www.hdp.org.tr/en/en/en/news/from-hdp/letter-by-hdps-co-chairs-to-un-secretary-general-ban-ki-moon/8862. Accessed 28 August 2017.

Heller, Sam. 2017. Turkish Crackdown on Humanitarians Threatens Aid to Syrians. https://tcf.org/content/report/turkish-crackdown-humanitarians-threatens-aid-syrians/. Accessed 30 August 2017.

Hurriyet Daily News. 2013. Poor Transparency Shadows Turkey’s Refugee Policy. http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/?PageID=238&NID=47639. Accessed 27 August 2017.

İHD. 2013. Yok Sayılanlar: Kamp Dışında Yaşayan Suriye’den Gelen Sığınmacılar İstanbul ÖrneğI. http://www.ihd.org.tr/images/pdf/2013/YokSayilanlar.pdf

Jenkins, J. Craig, and Bert Klandermans. 1995. The Politics of Social Protest: Comparative Perspectives on States and Social Movement. In The Politics of Social Protest. Comparative Perspectives on States and Social Movements, ed. J. Craig Jenkins and Bert Klandermans, 167–198. London: UCL.

Kaya, Ayhan. 2016. Syrian Refugees and Cultural Intimacy in Istanbul: “I feel safe here!” EUI Working Papers, RSCAS 2016/59.

Kirişçi, Kemal, and Elizabeth Ferris. 2015. Not Likely to Go Home: Syrian Refugees and the Challenges to Turkey – And the International Community. Brookings Institute Working Paper, no. 7 (September), Washington, DC.

Koopmans, Ruud, Paul Statham, Marco Giugni, and Florence Passy. 2005. Contested Citizenship: Immigration and Cultural Diversity in Europe. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

Kutlu, Zümray. 2015. Bekleme Odasından Oturma Odasına: Suriyeli Mültecilere Yönelik Çalışmalar Yürüten Sivil Toplum Kuruluşlarına Dair Kısa bir Değerlendirme, Istanbul.

MAZLUMDER. 2015. Türkiye’de Suriyeli Mülteciler: Istanbul Örneği – Tespitler, İhtiyaçlar, Öneriler, Istanbul.

Mezzadra, Sandro. 2004. Citizenship in Motion. Makeworlds 4 (February): 20–21.

Owens, Patricia. 2009. Reclaiming “Bare Life”?: Against Agamben on Refugees. International Relations 23 (4): 567–582.

Rellstab, Daniel H., and Christiane Schlote. 2015. Introduction. In Representations of War, Migration and Refugeehood. Interdisciplinary Perspectives, ed. Daniel H. Rellstab and Christiane Schlote. London: Routledge.

Tarrow, Sidney. 1996. States and Opportunities: The Political Structuring of Social Movements. In Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements, ed. Doug McAdam, John D. McCarthy, and Mayer N. Zald, 41–61. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tilly, Charles, and Sidney Tarrow. 2007. Contentious Politics. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

Yaylacı, Filiz Göktuna, and Mine Karakuş. 2015. Perceptions and Newspaper Coverage of Syrian Refugees in Turkey. Migration Letters 12 (3): 238–250.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Çelik, S. (2018). ‘We Have Become Refugees in Our Own Country’: Mobilising for Refugees in Istanbul. In: della Porta, D. (eds) Solidarity Mobilizations in the ‘Refugee Crisis’. Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71752-4_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71752-4_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-71751-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-71752-4

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)