Abstract

Recently, a number of researchers have sought to determine variables that may affect the ethical decision-making process. One of these variables is personal values that are guidelines for doing the ethical behavior. Personal values play an important role in the ethical decision-making process. In this study, we examined the effects of business students’ terminal and instrumental values on the ethical decision-making process. We considered ethical decision-making process as an ethical awareness, ethical orientation, and ethical intention. In order to measure ethical awareness, we tested whether a particular action was ethical/unethical based on ethical theories like justice, deontology, utilitarianism, relativism. Students’ intentions to perform ethical behaviors were measured by the probability of doing questionable action. Therefore, the purpose of this research is to investigate the effects of personal values on the students’ ethical decision-making criteria and intention to perform the ethical behavior. For this purpose, we used a self-administrated questionnaire method in order to collect data from business department students in Turkey. The 406 usable questionnaires were received from the voluntarily participated students in this research. During the analysis process, Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM) analysis method was used. The analysis results reveal that an instrumental value positively affects the students’ ethical decision-making criteria. Particularly, utilitarianism, justice, and relativism dimensions have the strongest effect on students’ intention to perform ethical behaviors.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

During the last decade, enlarged emphasis on ethics by the community has caused increased researchers’ interest in ethical decision-making area (Carlson et al. 2002). This interest has continued in business literature. There are numbers of models (Trevino 1986; Ferrell and Gresham 1985; Rest 1986; Jones 1991) that provide the theoretical framework for understanding ethical decision-making process in the literature. All of these models attempt to explain ethical decision-making processes from different perspectives.

In order to enhance ethical behavior, the factors that affect ethical decision-making must be understood as well as an understanding of ethical decision-making process. Personal value is one of the most studied factors that influence ethical decision-making in the literature. According to the literature, personal values are the determinant of behavior and having moral value means acting more ethically. The other factor that affects ethical decision-making is ethical philosophies. According to business ethics theorists, managers use ethical philosophies as a guideline when they make the ethical decision and see ethical philosophies as one of the most important factors that affect ethical judgment (Karande et al. 2002).

Business students are future professionals (e.g. accountant, marketer, manager etc.) of business areas in which ethical problems occur frequently. As a business professional, they will face ethical problems in their professional life. A better understanding of the personal value and ethical decision-making processes of business students can provide a better guidance for and enhance the ethical behavior of students’ private and professional life. In order to better understand the role of personal value, in this study, we researched the effect of the personal value of business students on the ethical decision-making, and intention to perform ethical behaviors. We specifically, investigate the effect of personal value on ethical decision-making criteria (justice, deontology, utilitarianism, relativism) which are used in the ethical decision-making process.

In the next section, the literature relating to the important factors investigated is reviewed. Personal value, ethical decision-making models, and ethical philosophies are discussed along with the research model and research hypotheses. This is followed by a description of data collection and analysis method, results, and conclusions.

2 Personal Value

There are a number of definitions of value in the literature. The most popular definition of value used in the business literature is that “a value is an enduring belief that specific mode of conduct or end-state of existence is personally and socially preferable to an opposite or converse mode of conduct or end-state of existence” (Rokeach 1973, p. 5). Rokeach defined two types of values: terminal and instrumental. Terminal values are “belief or conceptions about ultimate goals and desirable end-state of existence that are worth striving for” (e.g. world of peace, wisdom) whereas Instrumental values are “belief or conception about desirable modes of behavior that are instrumental to the attainment of desirable end-states” (e.g. love, honesty) (Rokeach 1979, p. 48).

Value is personally held and guidelines or permanent framework that influences and shapes the personal behavior (Oliver 1999; Windmiller et al. 1980; Finegan 1994; Fritzsche 1995; Akaah and Lund 1994). In other words, the value is determinants of attitudes and behaviors (Alteer et al. 2013). Thus, it can be said that if we can identify specific values that influence ethical behavior, we would have powerful tools for encouraging ethical behavior (Fritzsche 1995). In order to have powerful tools for value, educators and administrators should understand values, their influences, and the importance in business (Giacomino and Akers 1998).

There is a growing number of researchers that examined the relationship between personal values and ethical decision-making (e.g. Douglas et al. 2001; Finegan 1994; Akaah and Lund 1994; Fritzsche 1995; Shafer et al. 2001; Karacaer et al. 2009). Some of these found some degree of positive relationship between personal values and ethical decision-making. In this study, we investigate the effect of personal value on the business students’ ethical decision-making process.

3 Ethical Decision Making Models and Ethical Philosophies

Before explaining ethical decision-making models in the literature, we should define ethical decision-making. Ethical decision-making is “the process of identifying a problem, generating alternatives, choosing among them so that alternative selected to maximizes the most important ethical values while also achieving the intended goals” (Guy 1990, p. 39). In another definition, ethical decision-making is “the process by which individuals use their moral base to determine whether a certain issue is right or wrong” (Carlson et al. 2002, pp. 16–17). The most common expression of ethical decision-making is “decision making in situations where ethical conflicts are present” (Cohen et al. 2001, p. 321).

In order to provide a framework for ethical decision-making, theoretical ethical decision-making models are developed in the business literature. The contingency model of ethical decision-making suggests that multifaceted factors affect ethical decision-making. These factors are individual factors (knowledge, values, attitudes, and intentions) and organizational factors (significant others and opportunity) (Ferrell and Gresham 1985). An interactionist ethical decision-making model developed by Trevino (1986) explains ethical decision making by an interaction of individual (moral development) and situational (organizational culture, work characteristics) components. Hunt and Vitell (1986) developed the positive theory of marketing ethics by including moral philosophies deontological and teleological norms used in ethical decision-making (Hunt and Vitell 1986, 2006).

The other model is Rest’s (1986) ethical decision model that suggested four sequential stages that person must go through in ethical decision-making process. These stages are ethical awareness (recognitions of ethical problems), ethical orientation (ethical judgment or reasoning), ethical intention and ethical behavior. Ethical awareness is the first stage of the model and means the ability of an individual to recognize the ethical problems or issues in the situation. In order to behave morally, an individual must be aware of the ethical problem in the situations (Sweeney and Costella 2009). The second stage of the model is ethical orientation. In this stage, an individual tries to determine which alternative courses of action are ethically right or wrong. At the ethical intention stage, an individual decides to whether behaving in ethical or unethical manner. At the last stage of the model called ethical behavior, an individual behaves ethically or unethically. Jones (1991) added moral intensity construct to Rest’s (1986) ethical decision-making model. Moral intensity has six components. These components are the magnitude of consequences, social consensus, temporal immediacy, proximity, probability of effect, and concentration of effect. According to Jones (1991), components of moral intensity affect each stage of Rest’s (1986) ethical decision-making model.

Some of the theoretical ethical decision-making models (e.g., Hunt and Vitell 1986, 2006) saw moral philosophies (e.g. deontology, relativism) as a part of ethical decision process. Moreover, ethical philosophies are used as a guideline when individual/manager makes ethical decision (Singhapakdi 2004; Fritzsche 1991). Some of these philosophies are justice, deontology, utilitarianism, relativism. According to Cohen et al. (2001, p. 323), the justice ethical principle states that decision makers should focus on actions that are fair to all those involved and the deontology ethical theories state that people should follow to their unwritten obligations and duties when engaged in decision-making. Utilitarianism is to the extent to which an action leads to the greatest benefit for the greatest number of people (Forsyth 1992, p. 463). The relativism refers to the degree to which an individual rejects universal moral rules when making ethical judgment (Singhapakdi and Marta 2005).

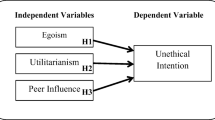

In this study, we measured ethical awareness, ethical orientation and ethical intention of the business student as an ethical decision-making stages by using Multidimensional Ethics Scale (MES) (developed by Flory et al. 1992; Cohen et al. 2001). Moreover, in order to determine which ethical philosophies students use as a guideline in the ethical decision-making process, we asked questions about justice, deontology, utilitarianism, relativism in MES. The aim of this study, therefore, is to investigate the effect of personal values on the students’ ethical decision-making criteria and intention to perform the ethical behavior. In this perspective, conceptual model and presumed relationships are presented in Fig. 1.

The research model shows the PLS-Path Model with seven latent variables presented by circles. Instrumental and terminal values are independent exogenous latent variables and justice, deontology, relativism, and utilitarianism are independent endogenous latent variables and behavioral intentions is a dependent endogenous latent construct in the research model. The relationships between the latent constructs are shown as single-headed arrows. Single-headed arrows show a predictive relationship between latent constructs. The hypotheses developed for this study in accordance with the related literature and research model are as follows:

-

H 1–4 : Instrumental values positively affect students’ four ethical decision-making criteria.

-

H 5–8 : Terminal values positively affect students’ four ethical decision-making criteria.

-

H 9–12 : Students’ ethical decision-making criteria (i.e. justice, deontology, relativism, and utilitarianism) positively affect students’ intention to perform ethical behaviors.

4 Research Methodology

In the research process, convenience sampling method and a self-administrated questionnaire method were used in order to collect data from the one state university business department students in Turkey. The analysis was carried out by using Partial Least Squares technique. Statistical analysis was performed via SmartPLS 3.0 software (Ringle et al. 2015).

4.1 Sampling and Data Collection

In this study, we used convenience sampling and a self-administrated questionnaire as a data collection method. Students that enrolled in undergraduate level classes from Osmaniye Korkut Ata University Faculty of Economics and Business Administration Department of Business students were selected as the sample. Two experienced academicians collected the data at the end of spring semester classes in 2016. The 406 valid questionnaires were obtained from voluntarily participated students in this research. Among the survey respondents, nearly 57% were female, 43% were male. Survey respondents’ age ranged from 18 to 25, and students’ average age was 21 years old (Stdev. 1.607). In terms of the monthly average household income, most of the respondents (75%) stated that they had an average household income level between 3000 and 3999 Turkish Liras.

4.2 Measurement of Variables

This study examined the effects of personal values on the students’ ethical decision-making criteria and intention to perform an ethical behavior. In order to measure students’ values, 18 instrumental and 18 terminal values, we used Rokeach Value Survey (Rokeach 1973) that is well known and widely used in business literature. For this study, students were asked to rate each value on a five-point scale, anchored with the bipolar adjectives and ranging from one meaning (unimportant) to five (important). In this study, we measured ethical awareness, ethical orientation, and ethical intention of business student as an ethical decision-making stage by using ten items Multidimensional Ethics Scale (MES), which contains four ethical philosophies (e.g. justice, relativism, utilitarianism, and deontology) as an ethical decision making criteria developed by Flory et al. (1992) and Cohen et al. (2001). During the data collection process, we used six scenarios in MES, which contains changing level of unethical situations. Students’ intention to perform ethical behavior was measured using two items developed by Randall and Fernandes (1991), Flory et al. (1992) and Cohen et al. (2001). The first item is “the probability that I would do the action is the low-high” and second item is “the probability that my peers and colleagues would do the action is the low-high”. Two items are measured via a five-point Likert scale, ranging from five meaning (low) to one meaning (high).

4.3 Data Analysis

In this study, to test our research hypotheses Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM) analysis technique was used. PLS-PM is a variance-based structural equation modeling analysis method for testing theoretical relations between latent variables (Willaby et al. 2015). The variance-based PLS-PM algorithm was originally invented by Wold (1974, 1982) and subsequently developed by many researchers (e.g. Bentler and Huang 2014; Dijkstra 2014; Dijkstra and Henseler 2015). PLS-PM maximizes the dependent latent variables’ explained variance by estimating partial model relationships in an iterative sequence of ordinary least squares regressions. In addition, PLS-PM emphasizes prediction while simultaneously relaxing the demands on data and specification of relationships (Hair et al. 2016). The estimation of PLS path model parameters is performed in four steps: first, an iterative algorithm that determines composite scores for each construct; second, a correction for attenuation for those constructs that are modeled as factors; third, parameter estimation; and finally, bootstrapping for inference testing (Henseler et al. 2016).

PLS-PM has some advantages over other SEM technique. For instance, PLS-PM analysis works efficiently with (a) complex theoretical models, (b) small sample size, (c) variable prediction goal, (d) both reflective and formative constructs are used, and finally, (e) non-normal data distributions (Willaby et al. 2015; Henseler et al. 2009; Chin 1998). Although many researchers mentioned some advantages of PLS-PM analysis method (e.g. Willaby et al. 2015; Reinartz et al. 2009; Esposito Vinzi et al. 2010; Henseler et al. 2009), in the literature, some researchers criticize the PLS-PM analysis method generally the four main directions. Firstly, PLS-PM produces biased parameter estimates. Secondly, PLS-PM offers no model overidentification tests. Thirdly, PLS-PM cannot correct for endogeneity problems in predictors, and finally, PLS-PM cannot accommodate measurement error (e.g. Rönkkö et al. 2015; McIntosh et al. 2014; Rönkkö and Evermann 2013). Having considered some advantages and disadvantages of PLS-PM method, the advantages of PLS-PM method outweighed the disadvantages. Therefore, PLS-PM analysis was used in order to test our research hypotheses. During the analyses process, we utilized SmartPLS 3 (Version 3.2.4) software (Ringle et al. 2015) to evaluate proposed research model.

5 Results

5.1 Reflective Measurement Model Assessment

PLS-PM is a composite-based analysis technique. According to Hair et al. (2016), PLS-PM consists of two elements. The first element is a structural model (also called the inner model in PLS-SEM) that displays the relationships between the constructs. The second element is the measurement models (also referred to as the outer models in PLS-SEM) that display the relationships between the constructs and the indicator variables. Henseler et al. (2009) state that PLS-PM analysis results should be evaluated in the two stages. In the first step, a measurement (outer) model result should be assessed and the next step, structural model results should be evaluated. In order to evaluate the psychometric properties of the reflective measurement model, we followed Hair et al. (2014) that suggested procedure in the analysis process. Ringle et al. (2010) indicated some evaluation criteria, for instance, outer loadings (>0.70), construct reliability (>0.60), AVE (>0.50), and indicator reliability (>0.50) must satisfy the minimum requirements for the reflective measurement model assessment.

As indicated in Table 1, all the outer loadings of the reflective constructs are statistically significant (P < 0.001) and well above the minimum threshold value of 0.70. The outer loadings of all construct indicators are significant and exceed 0.708, representing an adequate within-method convergent validity. Moreover, the composite reliability indices of all the reflective constructs exceed 0.70, representing internal consistency reliability of the measures. Furthermore, the AVE values (convergent validity) are well above the minimum recommended level of 0.50; hence, demonstrating convergent validity for all constructs. The internal consistency measures of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are well above the recommended level of 0.70. As shown in Table 1, PLS-PM analysis results indicate that all reflective constructs have high-level internal consistency reliability. In order to assess discriminant validity, the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion was used. The Fornell and Larcker criterion assumes that the square root of the AVE of each construct should be higher than the constructs’ correlation in the model. As can be seen in Table 1, all the square roots of the AVE values are higher than the correlations of constructs in the research model. The analysis result supports reflective measurement constructs’ discriminant validity. In general, the measurement method of research model could be deemed satisfactory for structural model assessment and hypothesis testing process.

5.2 Structural Model Assessment

Having confirmed the measurement model, as a reliable and valid, next step is to assess the relationships between latent variables. The evaluations of the structural research model build on the result of the standard model estimation, and the bootstrapping procedure (Hair et al. 2014). After performing the PLS-PM algorithm, the path coefficient estimates were obtained for the structural model relationships. The path coefficients statistical significance was estimated by means of bootstrapping routine (5000 subsample and 406 bootstrap cases). Table 2 shows the results of the structural relationship path coefficients, standard deviations for path coefficients, t-statistics values, P-values, and hypotheses test results.

As indicated in Table 2, six structural models were estimated for each of the six scenarios. PLS-PM analysis results indicate that instrumental value positively affects students’ ethical decision-making criteria (e.g. justice, relativism, utilitarianism, and deontology) dimensions (except for the dimension of deontology in the first scenario) for the five of the six scenarios. Therefore, H1, H2, H3, and H4 research hypotheses are supported. Particularly, instrumental value has the highest level of influence on justice and relativism dimensions. Furthermore, PLS-PM analysis results reveal that terminal value positively affects students’ ethical decision-making criteria (e.g. justice, relativism) dimensions (except for the dimension of relativism in the fourth scenario) for the five of the six scenarios. Thus, H5 and H7 research hypotheses are supported. On the other hand, terminal value positively affects deontology dimension for the only two (i.e. scenario 2 and 3) of the six scenarios tested. Therefore, H6 research hypothesis is not supported. In addition, terminal value positively affects utilitarianism dimension for the four (i.e. scenario 2, 3, 4, and 5) of the six scenarios investigated. Hence, H8 research hypothesis is generally supported. In general, PLS-PM analysis results reveal that instrumental and terminal values are significant predictors of students’ ethical decision-making criteria: especially, justice, relativism, and utilitarianism dimensions.

Table 2 provides support for our hypotheses related to whether or not ethical decision-making criteria have an effect on students’ intention to perform ethical behaviors. As Table 2 shows, utilitarianism ethical decision-making criterion positivity affects students’ intention to perform ethical behaviors for the five of the six scenarios (i.e. scenario 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). Therefore, H12 research hypothesis is supported. In addition, relativism positively affects students’ intention to perform ethical behaviors for the four of the six scenarios (i.e. scenario 1, 2, 3, and 5). Therefore, H11 research hypothesis is supported generally. Moreover, justice positively affects students’ intention to perform ethical behaviors for the four of the six scenarios (i.e. scenario 1, 4, 5, and 6). Therefore, H9 research hypothesis is supported generally. Unlike the other ethical decision-making criteria, deontology has not statistically significant influence on students’ intention to perform ethical behaviors for the all of the six scenarios. Thus, H10 research hypothesis is not supported. Overall, PLS-PM analysis results indicate that utilitarianism, relativism, and justice dimensions are significant predictors of students’ intention to perform ethical behaviors.

The coefficient of determination (R2) value and the Stone-Geisser’s (Q2) value are the commonly used measures of the structural model predictive accuracy and predictive relevance (Hair et al. 2016). The R2 value represents the amount of explained variance of the endogenous constructs in the structural model. In order to assess structural models’ predictive accuracy, we examined the R2 values of endogenous latent variables, which are shown in Table 3. The R2 values endogenous latent constructs range from 0.023 (for the scenario 2 deontology dimension) to 0.608 (for the scenario 4 ethical behavior intentions dimension), which indicates structural model’s predictive accuracy.

In order to evaluate the model’s predictive relevance, the Stone-Geisser’s (Q2) values were also examined. The Q2 value is an indicator of model’s predictive relevance and Q2 value bigger than zero for a certain reflective endogenous construct indicates the path model’s predictive relevance for a particular construct (Hair et al. 2014). Table 3 also shows the Stone-Geisser’s (Q2) value of all endogenous constructs. During the blindfolding analysis procedure, we used cross-validated redundancy values for the model’s predictive relevance, all the Q2 values are above the zero (ranging from 0.013 for the scenario 6 utilitarianism dimension to 0.594 for the scenario 4 ethical behavior intentions dimension), which supports the model’s predictive relevance for the endogenous construct.

6 Conclusions

This study examined the effects of personal values on the students’ ethical decision-making criteria and intention to perform the ethical behavior. We found that instrumental value positively affects students’ ethical decision-making criteria (e.g. justice, relativism, utilitarianism, and deontology) in five scenarios. In the first scenario, we found that instrumental value does not have significant effect on deontology. In addition, instrumental value has the highest level of influence on justice and relativism. Furthermore, we found that terminal value positively affects students’ ethical decision-making criteria (justice, relativism) for the four of the six scenarios. On the other hand, terminal value positively affects deontology for the only two (i.e. scenario 2 and 3) of the six scenarios tested. In addition, terminal value positively affects utilitarianism for the four (i.e. scenario 2, 3, 4, and 5) of the six scenarios investigated. In general, we found that instrumental and terminal values are significant predictors of students’ ethical decision-making process: particularly, justice, relativism, and utilitarianism. These results agree with the findings of previous research on the effects of personal values on ethical decision-making process (e.g., Ferrell and Gresham 1985; Finegan 1994; Fritzsche 1995; Akaah and Lund 1994; Douglas et al. 2001). Therefore, this study suggests that if the education program can improve the personal value (especially instrumental value) of the business students, the more ethical behavior can be expected from the students.

In addition, we found that utilitarianism positively affects students’ intention to perform ethical behaviors for the five of the six scenarios (i.e. scenario 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). In addition, relativism positively affects students’ intention to perform ethical behaviors for the four of the six scenarios (i.e. scenario 1, 2, 3, and 5). Moreover, justice positively affects students’ ethical behavior intentions for the four of the six scenarios (i.e. scenario 1, 4, 5, and 6). Unlike the other ethical decision-making criteria, deontology does not have a significant influence on students’ intention to perform ethical behaviors for the all of the six scenarios. Overall, we found that utilitarianism, relativism, and justice are significant predictors of students’ intention to perform ethical behaviors. These findings are in line with the literature that indicated moral philosophies affect the ethical decision-making process. Particularly, Cohen et al. (2001) found that deontology and justice have the strongest effects while relativism has the weakest effects on the ethical decision-making process of business students and accounting professionals.

As a result, our study reveals that personal value affects ethical decision-making criteria and then these criteria affect ethical intentions. The findings of this study offer additional insight in the area of the students’ ethical decision-making process. However, as with any survey research, this study has some limitations. The first limitation of this study is that we used a non-probability convenience sampling method. This sampling method restricted the generalizing of the study results to the population. Therefore, future research should use the probability sampling method and may retest the research model with the data from the MBA students and professionals. In addition, the further study should use other variables (e.g. age, gender, income, culture) that might affect ethical decision-making. In relation to these considerations, more research on this topic needs to be undertaken before the effects of personal values on ethical decision-making criteria and ethical behavioral intentions are more clearly understood.

References

Akaah, I. P., & Lund, D. (1994). The influence of personal and organizational values on marketing professionals’ ethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(6), 417–430.

Alteer, A. M., Yahya, S. B., & Haron, M. H. (2013). Auditors’ personal value and ethical judgment at different levels of ethical climate: A conceptual link. Journal of Asian Scientific Research, 3(8), 862–875.

Bentler, P. M., & Huang, W. (2014). On components, latent variables, PLS and simple methods: Reactions to Rigdon’s rethinking of PLS. Long Range Planning, 47(3), 138–145.

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Wadsworth, L. L. (2002). The impact of moral intensity dimensions on ethical decision making: Assessing the relevance of orientation. Journal of Managerial Issues, 14(1), 15–30.

Chin, W. (1998). Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly, 22(1), 7–16.

Cohen, J. R., Pant, L. W., & Sharp, D. J. (2001). An examination of differences in ethical decision-making between canadian business students and accounting professionals. Journal of Business Ethics, 30(4), 319–336.

Dijkstra, T. K. (2014). PLS’ janus face–response to professor Rigdon’s ‘rethinking partial least squares modeling: In praise of simple methods’. Long Range Planning, 47(3), 146–153.

Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316.

Douglas, P. C., Davidson, R. A., & Schwartz, B. N. (2001). The effect of organizational culture and ethical orientation on accountants’ ethical judgments. Journal of Business Ethics, 34(2), 101–121.

Esposito Vinzi, V., Trinchera, L., & Amato, S. (2010). PLS path modeling: From foundations to recent developments and open issues for model assessment and improvement. In V. Esposito Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications (Springer handbooks of computational statistics series) (Vol. 2, pp. 47–82). Heidelberg: Springer.

Ferrell, O. C., & Gresham, L. G. (1985). A contingency framework for understanding ethical decision making in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 49(3), 87–96.

Finegan, J. (1994). The impact of personal values on judgments of ethical behavior in workplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(9), 747–755.

Flory, S. M., Phillips, T. J., Reidenbach, R. E., & Robin, D. P. (1992). A multidimensional analysis of selected ethical issues in accounting. The Accounting Review, 67(2), 284–302.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Forsyth, D. R. (1992). Judging the morality of business practices: The influence of personal moral philosophies. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(5), 461–470.

Fritzsche, D. J. (1991). A model of decision-making incorporating ethical values. Journal of Business Ethics, 10(11), 841–852.

Fritzsche, D. J. (1995). Personal values: Potential keys to ethical decision making. Journal of Business Ethic, 14(11), 909–922.

Giacomino, D. E., & Akers, M. D. (1998). An examination of the differences between personal values and value types of female and male accounting and nonaccounting majors. Issues in Accounting Education, 13(3), 565–584.

Guy, M. E. (1990). Ethical decision making in everyday work situations. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Advances in International Marketing, 20, 277–319.

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (1986). A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing, 6(1), 5–16.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (2006). The general theory of marketing ethics: A revision and three questions. Journal of Macromarketing, 26(2), 143–153.

Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. The Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395.

Karacaer, S., Gohar, R., Aygün, M., & Sayın, C. (2009). Effects of personal values on auditor’s ethical decision: A comparison of Pakistani and Turkish professional auditors. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 53–64.

Karande, K., Rao, C. P., & Singhapakdi, A. (2002). Moral philosophies of marketing managers a comparison of American Australian, and Malaysian cultures. European Journal of Marketing, 36(7/8), 768–791.

McIntosh, C. N., Edwards, J. R., & Antonakis, J. (2014). Reflections on partial least squares path modeling. Organizational Research Methods, 17(2), 210–251.

Oliver, B. L. (1999). Comparing corporate managers’ personal values over three decades, 1967–1995. Journal of Business Ethics, 20(2), 147–161.

Randall, D. M., & Fernandes, M. F. (1991). The social desirability response bias in ethics research. Journal of Business Ethics, 10(11), 805–817.

Reinartz, W., Haenlein, M., & Henseler, J. (2009). An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 26(4), 332–344.

Rest, J. R. (1986). Moral development: Advances in research and theory. New York: Praeger.

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Will, A. (2010). Finite mixture partial least squares analysis: Methodology and numerical examples. In V. Esposito Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications (Springer handbooks of computational statistics series) (pp. 195–218). Berlin: Springer.

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J. M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York: The Free Press.

Rokeach, M. (1979). From individual to institutional values: With special reference to the values of science. In M. Rokeach (Ed.), Understanding human values (pp. 47–70). New York: The Free Press.

Rönkkö, M., & Evermann, J. (2013). A critical examination of common beliefs about partial least squares path modeling. Organizational Research Methods, 16(3), 425–448.

Rönkkö, M., McIntosh, C. N., & Antonakis, J. (2015). On the adoption of partial least squares in psychological research: Caveat emptor. Personality and Individual Differences, 87, 76–84.

Shafer, W. E., Morris, R. E., & Ketchand, A. A. (2001). Effect of personal values on auditors’ ethical decisions. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 14(3), 254–277.

Singhapakdi, A. (2004). Important factors underlying ethical intentions of students: Implications for marketing education. Journal of Marketing Education, 26(3), 261–270.

Singhapakdi, A., & Marta, J. K. (2005). Comparing marketing students with practitioners on some key variables of ethical decisions. Marketing Education Review, 15(3), 13–25.

Sweeney, B., & Costella, F. (2009). Moral intensity and ethical decision–making: An empirical examination of undergraduate accounting and business students. Accounting Education, 18(1), 75–97.

Trevino, L. K. (1986). Ethical decision making in organizations: A person-situation interactionist model. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 601–617.

Willaby, H. W., Costa, D. S., Burns, B. D., MacCann, C., & Roberts, R. D. (2015). Testing complex models with small sample sizes: A historical overview and empirical demonstration of what partial least squares (PLS) can offer differential psychology. Personality and Individual Differences, 84, 73–78.

Windmiller, M., Lambert, N., & Turiel, E. (Eds.). (1980). Moral development and socialization. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Wold, H. (1974). Causal flows with latent variables: Partings of the ways in the light of NIPALS modeling. European Economic Review, 5(1), 67–86.

Wold, H. (1982). Soft modeling: The basic design and some extensions. In K. G. Jöreskog & H. Wold (Eds.), Systems under indirect observation. Causality, structure, prediction (Vol. II, pp. 1–54). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Turk, Z., Avcilar, M.Y. (2018). An Investigation of the Effect of Personal Values on the Students’ Ethical Decision-Making Process. In: Bilgin, M., Danis, H., Demir, E., Can, U. (eds) Eurasian Business Perspectives. Eurasian Studies in Business and Economics, vol 8/1. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67913-6_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67913-6_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-67912-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-67913-6

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)