Abstract

There is growing awareness amongst retail investors of the importance of environmental, social, and governance (ESG ) factors to the performance of their stocks. The same factors impact their lives from a broader societal and economic perspective. Institutional investors have incorporated ESG issues into their proxy voting and corporate engagement. Retail investors who invest in stocks directly have the same voting rights, and collectively a similar power, but data shows that their voting rates have declined precipitously over the past forty years. This chapter traces the history of property rights and proxy voting, examines them within the current regulatory context, and posits that economic rights have been well protected but ownership rights have been neglected. An established framework for stages of capitalism is re-imagined, situating retail investors’ disengagement from the proxy process and highlighting suggestions to regulators for addressing the proxy voting gap.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Shareholders of public corporations are entitled to two property rights : a share of the economic benefit, usually through dividends or capital gains; and a means of asserting their ownership views by voting their shares in person or by proxy in corporate annual general meetings (AGMs) or other special meetings.Footnote 1 Economic rights have developed over centuries (Macfarlane 2002) and remain strong today (La Porta et al. 1999). Shareholders may be large institutions or small retail (individual) owners, but whether they invest in a corporation’s shares directly or through intermediaries (e.g. mutual funds), lawmakers and regulators have ensured they receive an equitable share of profits.

However, the effective exercise of ownership rights has bifurcated since the 1970s; institutions have increased their proxy voting as a core element of responsible investment (Clark and Hebb 2004), while retail investors ’ proxy voting rates have decreased substantially (Broadridge 2015; U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 1976). Retail shareholders own approximately half of publicly traded shares (U.S. Federal Reserve Board 2014a), and if responsible investment is to continue its growth trajectory (Global Sustainable Investment Alliance 2015), their participation must be encouraged.

Institutional investors began to vote their proxies to influence companies’ governance (G) and later their environmental (E) and social (S) practices (now collectively labelled ESG ). The re-assertion of ownership rights had its origin in two developments: the enactment in 1974 of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) in the United States, which established a fiduciary duty for pension plan managers and required them to vote proxies in plan-holders’ best interests; and the connection of ESG issues to long-term financial performance (Clark and Hebb 2004). The incorporation of ESG factors into the selection of stocks and the voting of proxies—the core activities of responsible investment —appears to pose a challenge to retail investors under the current regulatory system.

What began as a fiduciary responsibility and means to improve financial performance has expanded from company-specific ESG considerations to encompass broader aspects of capitalism and society. For example, engagement with companies about CEO pay is a governance issue with a direct financial impact—each dollar not paid to a CEO is an additional dollar to be split amongst shareholders. The same CEO pay issue can also be considered within the context of the current era of liberal (free-market) capitalism that, in addition to generating global wealth, has produced both high levels of domestic income inequality and the global financial crisis (Kotz 2009; Milanovic 2016). Proxy voting is a point of intersection between individual property rights and capitalism.

Recommendations to re-engage retail investors in responsible investment will be most effective if they reference: the history of property rights and the development of the corporation, the social context of liberal capitalism, how the retail brokerage and proxy systems serve retail investors , and the impact of recent changes within the brokerage and proxy systems.

Regulators focus predominantly on operational issues within the proxy system, such as end-to-end reconciliation of vote totals (Canadian Securities Administrators 2013; U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2015b). Consideration of low retail participation rates is typified by suggestions to vary the colour of envelopes to entice higher response (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2015b), though on occasion more comprehensive consideration is given (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2010). All suggestions to improve the proxy system should be encouraged, but re-engagement of retail investors requires re-imagination of the system within the broader context outlined here. The primary focus is on the United States, but where helpful reference will be made to other jurisdictions, in particular England for historical context and Canada for comparison of regulatory frameworks.

2 Stages of Capitalism: The Linear Model(s)

Academic models can be useful for illustrating relationships over time or within a system. Robert Clark’s ‘Four Stages of Capitalism’ model shows the dissociation of owners’ economic rights over time (Clark 1981). Clark wrote that capitalism could be divided into four overlapping stages, and Clark (no relation) and Hebb (2004) later added a fifth:

-

1.

an entrepreneurial start in the nineteenth century when legal frameworks were first established and corporations grew in popularity, size, and scope under owner/operators;

-

2.

a second stage leading up to the Great Depression when professional business managers were employed, which introduced the agency issue and the separation of economic interests (capital) from control;

-

3.

a third stage beginning in the early 1900s and peaking in the 1960s, which introduced financial intermediaries such as investment managers, which further separated capital owners’ economic interests from the selection of companies;

-

4.

fourth, beginning in the late 1970s, a second set of financial intermediaries which directed even smaller pools of capital such as employee retirement savings to different investment managers;

-

5.

fifth, rising in use and impact in the new millennium, the incorporation of pension funds’ active engagement with companies on ESG issues (Clark and Hebb 2004).

The successive models proposed by Clark, and then Clark and Hebb, are intuitive because the stages are chronological, but they mix the treatment of economic and ownership rights and are therefore incomplete. The economic and ownership components of property rights are combined at the first stage but separate at the second. Stages three and four describe financial intermediaries that separate owners from their capital, yet economic rights remained strong, and beneficial share-owners continued to receive the financial benefits to which they were entitled. The fifth stage re-introduces ownership rights (Fig. 8.1).

This chapter introduces a new pentagonal ‘Stages of Capitalism’ model which shows the evolution of economic and ownership rights within capitalism. Both the linear and pentagonal models share the first two stages in common, but the pentagonal model clarifies the relationship between economic and ownership rights by combining stages three and four and drawing a connection between the final and the second stages to make a closed rather than linear system. This situates responsible investment within the current era of liberal capitalism, highlights a gap in the exercise of ownership rights by retail (minor) investors , and serves as a foundation from which to recommend improvements to the proxy system. The new model allows the recommendations to be appreciated in support of two broad goals: to nudge corporate ESG behaviour towards social norms rather than just legal requirements and to re-engage retail investors within liberal capitalism.

Before returning to the pentagonal model, the first two stages of capitalism will be examined—the evolution of property rights and the development of the corporation—drawing on events of English history and then shifting to the American context. Further, a helpful chronological framework will be introduced—the alternating eras of liberal and regulated capitalism described by Kotz (2015)—which also relies heavily on property rights and corporate development and the philosophical underpinnings of the social contract introduced by Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. Figure 8.2 shows the pentagonal model within the evolution of property rights and the stages of capitalism, which are described next.

3 Property Rights and Corporations

3.1 Property Rights

Writing during the uncertainty of the English Civil War, Thomas Hobbes in his book Leviathan reasoned that in the absence of some form of organization, individuals would be in perpetual conflict. It would be a ‘free-for-all’ as individuals fought to obtain goods or protect those they already possessed and the resulting life of man would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short” (Hobbes 2009). Hobbes proposed that individuals instead should enter in to a social contract whereby they would trade some of their rights to an all-powerful state in return for protection of their property and the ability to emerge from their ‘state of nature’—a proposition that contained elements of liberalism and totalitarianism.

Writing a short time later, John Locke proposed his own version of a social contract for the protection of rights, which formed the basis of liberalism (Taylor 2010), and was incorporated into the founding principles of the United States (Fukuyama 1992; Hartz 1991).

Government s have responded to the unequal impact of capitalism by considering the best ways to maintain or adapt the social contract. These have included alternating eras in the United States in which the government’s role has been limited to the effective protection of property rights (liberal capitalism) or expanded to moderate certain aspects (regulated capitalism ) (Kotz 2015).

Legal historian F.W. Maitland chronicled the evolution of laws and precedents from Anglo-Saxon times—our common law—which led to a new form of organization based on the individual. This gave rise to three important structures—the Trust, the Corporation, and the Stock Exchange—and over time developed into our liberal market system (Macfarlane 2002; Michie 2001b).

3.2 The Trust

Macfarlane (2002) notes Maitland’s conclusion that the Trust was a unique institutional structure which sprang from England’s impersonal, contract based economy in the thirteenth century. The Trust could be used to pass property from one generation to the next, or to establish entities engaged in public good or charity, and to maintain the property’s independence from king or state. “The private man who creates a charitable trust does something that is very like the creation of an artificial person, and does it without asking leave of the State” (Fisher 2015, pt. 1704).

3.3 The Stock Market

“The origins of the modern global securities market lie in medieval Italy” (Michie 2007, p. 2). From that thirteenth century origin, securities trading shifted north over the centuries to reflect new trading and commercial centres, establishing successive hubs in Bruges, Antwerp, and Amsterdam.

State directed commerce and trade, known as mercantilism, led to the creation by government charter in 1602 of the Dutch East India Company, which raised permanent capital through the issuance of a large number of shares to the public to finance its trading operations (Michie 2007). Though the English East India Company predated the Dutch one and was important for its role in popularizing the joint-stock company form, it was very closely held and therefore had little impact on the development of the London securities market.

Later that century the South Seas Company was chartered in England and the similarly purposed Mississippi Company in France. They enticed investors into an investment frenzy and market bubble. The inevitable market collapses led the British government to pass “the Bubble Act of 1720 [which] made illegal the formation of any unincorporated joint stock company, and the issue of transferable shares therein” (Johnson 2010, p. 114) and which “set back the formation of corporations (incorporation) in the UK for one hundred years” (Mayer 2013, p. 101). The Bubble Act was repealed in 1825, and the subsequent passing of four separate acts between 1844 and 1862 laid the legal framework for corporate capitalism which brought exponential growth in material wealth to much of the world (Johnson 2010).

Michie offers a helpful definition of a stock exchange by which he identifies the first stock exchange forming in London in March 1801.

A market where specialized intermediaries buy and sell securities under a common set of rules and regulations through a closed system dedicated to that purpose. (Michie 2001a, p. 5)

In the United States, the Buttonwood Agreement of 1792 codified New York’s informal system for trading bonds and established what would become the New York Stock Exchange, but it did not yet meet Michie’s definition as a closed system.

3.4 The Corporation (Stage One)

3.4.1 Market Liberalization

The centuries long thread of customs, practice, and legislative progress outlined by Maitland helps explain England’s unique standing (Macfarlane 2002), but Johnson (2010) notes that in practice there were still two types of changes needed before more fertile ground would allow the joint-stock company to flourish. First, the individual needed more opportunity within the marketplace and second, better protection before the courts. Both issues remain fundamental to liberal capitalism today, with the former represented by various global trade agreements (Baumol et al. 2007) and the latter by strong property rights (La Porta et al. 1999).

3.4.2 Corporate Ownership and Proxy Voting

Like European mercantilist corporations, Dunlavy (2004, p. 5) writes that in the United States, “the early corporation was a state-created, legal ‘person’ with well-defined powers.” Shareholders were active rather than passive corporate owners, ‘trustees of its capital’ (Dunlavy 2004, p. 5). Property rights—economic and ownership—were intact, and the corporation was subordinate to the state, consistent with the social contract proposed by Hobbes and Locke. Dunlavy continues:

Then, in the last two decades of the nineteenth century, a momentous change occurred: the corporation came to be regarded, on the one hand, as intrinsically private – that is, as arising not out of state action but out of the private actions of individuals – and ultimately, on the other hand, as a “natural person.” (Dunlavy 2004, p. 6)

The same change had evolved over centuries in England, and in both places it produced the same result; “the once active member [shareholder] became merely a passive investor in the corporation” (citing Horowitz, Dunlavy 2004, p. 6). Corporations began increasingly to raise capital and trade through stock exchanges, further dissociating formerly ‘active’ owners.

How shareholders exercised their ownership rights—their proxy votes—also has a long history. Dunlavy summarizes the methods as bound by two extremes—a democratic one vote per shareholder (similar to how we elect governments); and a plutocratic one vote per share (which gives larger shareholders greater input, and is the system we generally use today for public corporations)—with a variety of mixed methods that gave a declining number of additional votes for increased shareholdings. The democratic form was inherent to the membership orientation of mercantilist corporations and professional guilds (and would be familiar to members of co-operatives today), but by the late 1700s sustained debate about the merits of plutocratic voting rights led to partial adoption of the other two methods. By the early to mid-1800s the democratic, mixed, and plutocratic forms were equally common, and by the late 1800s plutocracy was the norm (Dunlavy 2004).

The establishment of the corporation as a ‘natural person’ with inherent rights, the dissociation of minority shareholders’ ownership rights through plutocratic voting, and the geographic distribution of ownership via stock exchanges all served to cleave the formerly combined economic and ownership rights. The dissociation continued in the following decades and has accelerated more recently to the point where proxies are seldom voted by retail investors (Broadridge 2015).

Plutocracy and minority shareholding also contributed to the agency issue described below. In the late 1800s, however, the shareholders’ primary concern was receipt of their fair share of the profits. Questions of the corporation’s place within the social contract wouldn’t be raised for almost fifty years as part of corporate social responsibility, and the value of proxy votes to engage corporations on ESG issues wouldn’t be considered for almost a century.

In the meantime, on both sides of the Atlantic, the first stage of capitalism—that of the entrepreneur—was dawning. Well-known figures such as the industrialists, bankers, and speculators Cornelius Vanderbilt, John Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, and Jay Gould were emerging as owner-operators, and they enjoyed both the economic and ownership rights of their companies (Geisst 2012; Kotz 2015). The figures have been referred to as ‘Robber Barons’ and the era as the Gilded Age, and it marked the beginning of the first period of liberal market capitalism (Kotz 2015) and the first stage of capitalism on both the linear and pentagonal models.

3.4.3 Eras of Capitalism: Liberal Versus Regulated

Classic Liberalism, which built upon Hobbes’ and Locke’s social contract and which from the eighteenth century had equated liberty with property rights , began to give way under the new corporate form to regulated capitalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Gaus et al. 2015; Kotz 2015). It was based upon three beliefs: that markets based upon private property could be unstable, that government could help mitigate the instability, and that “property rights generated an unjust inequality of power that led to a less-than-equal liberty … for the working class” (Gaus et al. 2015, pp. 8–9).

Responding to the excesses of the Robber Barons, in 1900 a new era of regulated capitalism began under the leadership of the banks, which desired a more stable environment for growth and control. Popular support was provided by two social movements, the Progressives and the Socialists (Kotz 2015), and the period became known as the Progressive Era. After World War I, it was followed by a second period of unregulated liberal capitalism known as the Roaring Twenties, which featured both housing market and stock market bubbles and ended in the Great Depression.

In the early years of the Great Depression, two academics, Adolf Berle and Merrick Dodd, debated “whether corporations should be treated as public institutions with obligations to mitigate the [economic] system’s inherent instability, even if these obligations conflicted with maximizing shareholder returns” (Bratton and Wachter 2008, p. 102). It had much in common with the Progressive era’s regulated capitalism and was an early consideration of whether corporations had a ‘social responsibility ’ in addition to profit maximization (Bratton and Wachter 2008, p. 102). It was also an argument that would resurface decades later as part of responsible investment .

It wasn’t until after WWII that a second sustained era of regulated capitalism began, this time with a post-war cooperative spirit between labour and capital, the promise of new multi-lateral institutions and globalizing trade and a new economic keel—Keynesian economics, in which government fiscal policy helped stabilize the natural boom-and-bust business cycles. This Golden Age of regulated capitalism produced more than two and a half decades of high growth which was “widely shared among most, if not all, of the population” (Kotz 2015, pt. 876). Eventually it was met by new challenges, including declining corporate profits, high inflation, and high unemployment. According to Kotz (2015), the challenges were met by business’ abandonment of collective bargaining, corporatisation of media and politics, and a new (free-market) economic orthodoxy led by Milton Friedman and Frederick Hayek. A third era of liberal capitalism began, referred to as Neoliberalism, starting symbolically with the elections of Thatcher in the United Kingdom and Reagan in the United States.

Neoliberalism is … a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights , free markets, and free trade. (Harvey 2005, pp. 1–2)

The definition could easily describe the Gilded Age, the Roaring Twenties, or the Victorian era’s legislative changes that established the corporation. As in the Roaring Twenties, it set the US economy on a path of corporate expansion and wealth generation but also asset bubbles and growing inequality (Milanovic 2016; Picketty 2014). From 1986 to 2012, for example, “almost half of U.S. wealth accumulation [was] due to the top 0.1% alone,” and wealth inequality was “almost as high as in the 1916 and 1929 historical peaks” (Saez and Zucman 2016, pp. 521,523). Visible new members of the ultra-wealthy cohort include the newly stock-optioned super manager class of corporate executives, who have enriched themselves on the back of a narrowing shareholder base (Picketty 2014; U.S. Federal Reserve Board 2014b).

On a global scale, Neoliberalism has delivered uneven results. Many developing (particularly Asian) economies have benefitted enormously, while in the West it has “failed to deliver palpable benefits to the majority” (Milanovic 2016, p. 21). Instead, it has fostered populist opposition evidenced by: the 1999 Seattle World Trade Organisation protests, the 2011 Occupy Wall Street protests, and the 2016 Brexit vote and US election rhetoric. Kotz (2015) identifies popular support as an important catalyst in the see-saw shifts between liberal and regulated eras of capitalism and notes that high levels of inequality have acted as harbingers of change. He concludes that the global financial crisis in 2008 marks an inflection point away from Neoliberalism, but as transitions can take time (fifteen years between the Roaring Twenties and the Golden Era), he does not specify the attributes of the next era. The pentagonal Stages of Capitalism model introduced in this paper will show that responsible investment could be both the social catalyst for and the economic foundation of the fourth stage of capitalism. The second and third stages must be examined first.

3.5 The Agency Issue (Stage Two)

Writing at the end of the Roaring Twenties, Berle considered another aspect of the corporation—the agency issue —in which professional business managers are employed, and the suppliers of capital (i.e. the company’s owners) are separated from both their economic rights and ownership rights (Berle 1928).Footnote 2 An informational asymmetry between management and owners shifts control and economic return from the latter to the former and marks the onset of the second stage of capitalism on the linear and pentagonal models. The owner-operator Robber Barons faced no agency issue but increased public ownership through stock markets diluted control—from a single owner, to a small group of owners, and ultimately to a larger group of dispersed shareholders.

A 1976 paper by Jensen and Meckling re-examined the agency issue and codified it as “the reduced value of the firm caused by the manager’s consumption of perquisites” (Jensen and Meckling 1976, p. 327), essentially a financial tug-of-war over money (economic rights) between managers and shareholders. The paper ignored ownership rights, and any notion of corporate social responsibility was dismissed (Jensen and Meckling 1976). The dual nature of shareholder rights had been reduced to a narrow financial interest. Twenty-five years later, the shift in perspective had become dominant—the financial aspect of property rights had become the normative lens for economists—and it coincided with the shift to Neoliberal capitalism.

The shareholder-oriented model does more than assert the primacy of shareholder interests, however. It asserts the interests of all shareholders, including minority shareholders. More particularly, it is a central tenet in the standard model that minority or non-controlling shareholders should receive strong protection from exploitation at the hands of controlling shareholders. In publicly traded firms, this means that all shareholders should be assured an essentially equal claim on corporate earnings and assets. (Hansmann and Kraakman 2001, p. 442)

Even core governance issues within responsible investment , such as CEO pay, were reduced to an agency issue (Bebchuk and Fried 2003), with no consideration of its contribution to inequality or impact on society. If the economic rights of minority (retail) shareholders could be protected through statutes, regulation , and the actions of larger shareholders (La Porta et al. 1999), then ownership (proxy) rights became secondary.

4 Retail Investors

4.1 Stock Ownership

Aggregate ownership may be measured in two ways: the number of retail investors who own stock and the percentage of stock owned by retail investors . First, recent survey data indicate that in 2013 approximately half of the households in the United States owned stock in some form, with about 14% holding it directly in registered or street formFootnote 3 and the remainder indirectly through, for example, mutual funds (U.S. Federal Reserve Board 2014a). This is consistent with 2013 and 2016 US Gallup polls, both of which found 52% of adults owned stock either individually or with a spouse (Gallup 2016). The widespread ownership testifies to the importance of retail investors to establishing the popular support that Kotz (2015) notes is essential during shifts between liberal and regulated capitalism . As will be shown below, the 14% of investors who hold stocks directly face challenges, but according to the pentagonal model of capitalism, also offer great promise (Fig. 8.3).

Retail stock ownership: families with stock holdings (Source: U.S. Federal Reserve Board (2016))

Second, in 2015 individual investors owned approximately one half of the total value of corporate stocks, with about 40% held directly and 24% through mutual funds (U.S. Federal Reserve Board 2016).Footnote 4 This is a decline from direct ownership of approximately 93% in 1945 and 85% in 1965 but still substantial (citing Goldman Sachs, Ro 2015; Rosenthal and Austin 2016). The size of retail investors ’ corporate ownership highlights the importance of their proxy votes to full realization of responsible investment goals.

If both aspects of ownership are taken together, they show that approximately 14% of households account for 40% of direct corporate stock ownership (and likely some of the indirect ownership), while 36% of households account for the balance of the 24% of indirect ownership.

4.2 Investing in Stocks: Three Channels

To invest in stocks directly, retail shareholders usually utilize one of three brokerage firm channels: discount, full-service, or portfolio management. Each brokerage channel entails, respectively, increasing levels of service, advice, and responsibility , with related implications for the service and advice for proxy voting. Though they are regulated by many different organizations, brokerage activities are primarily overseen by the self-regulatory organization Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

Brokerage firms serve an essential role in capital markets. Historically, they charged a commission per transaction—they controlled access to the market and were paid for the brokering of a trade between buyer and seller—but over decades have steadily increased the scope and value of their services.

Like the informational asymmetry between company management and shareholders identified by Berle (the agency issue ), there is often one between brokerage firms and the investors they serve. This has led to regulations that specify different levels of responsibility to clients depending upon the intermediary’s role and relationship, but the rules for economic advice—that is, investment in a stock—are inconsistent with those for ownership rights or the voting of proxies. This mismatch at the brokerage level may be a key contributor to the decline in retail investor proxy voting. Only at the highest level of responsibility, that of a fiduciary, are the responsibilities equal.

4.2.1 Fiduciary Duty

Fiduciary duty may be based in common law or prescribed by statute. The “relationship is one in which one party (the fiduciary) exercises discretionary power over the significant practical interests of another (the beneficiary)” (Miller 2014, p. 69). FINRA licensed brokers do not have a fiduciary duty . However, if they also become licensed to provide portfolio management services under the Securities and Exchange Commission, they will be required to act as fiduciaries when ‘exercising discretionary power’ over the selection of investments and in the voting of proxies.Footnote 5

The situation is different in Canada where brokers may, and portfolio managers do have a fiduciary duty based in common law rather than statute when licensed under that country’s self-regulatory counterpart. The Canadian system lacks the clarity of the SEC’s statutory directive to its portfolio managers regarding fiduciary duty and the voting of client proxies (Canadian Securities Administrators 2012a; U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2003). While the definition of a fiduciary is clear, its application can be uneven, and this poses a challenge to effective responsible investment by retail investors in the United States by brokers and in Canada by both brokers and portfolio managers.

Both the United States and Canada are considering changes to increase the number of advisers subject to a fiduciary standard (Canadian Securities Administrators 2012a; U.S. Department of Labor 2017). The proposed US legislation has withstood a court challenge by industry participants (Lynn 2017) but was put on hold shortly after President Trump took office in 2017 (Trump 2017). The American and Canadian initiatives are notable for their stated goals of improving the consistency and level of advice to retail investors regarding economic interests, but are also important for their potential impact on ownership rights and proxy voting, like ERISA’s impact on pension managers after 1974.

In some instances, a fiduciary duty will be imposed upon an adviser due to their professional designation, regardless of their licensing. For example, Chartered Financial Analysts and candidates for the CFA charter “… must act for the benefit of their clients and place their clients’ interests before their employer’s or their own interests” (CFA Institute 2014, p. 2). Professional organizations can support regulators by strengthening their own fiduciary standards and by linking them to the principles of responsible investment and enhanced shareholder returns.

4.2.2 Full-Service Brokerage

Full-service brokerage firms offer trade execution, settlement, and custodial services. They employ brokers—defined as “any person engaged in the business of effecting transactions in securities for the account of others” (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2008a, p. 4)—who offer advice tailored to each retail investor’s circumstances. In the words of one major US brokerage firm, “when handling a brokerage account, your Financial Advisor must have a reasonable basis for believing that any recommendation is suitable for you, but will not have a fiduciary or investment advisory relationship with you” (Morgan Stanley 2014, p. 2).

Proxies are usually delivered directly to investors , but unlike the economic advice provided regarding the suitability of a stock, usually no advice is offered regarding how to vote. Brokers do have some discretion to vote proxies—for beneficial rather than registered owners who hold their shares electronically at the brokerage firm (see following section)—but only on routine matters. This has the effect of increasing quorum and voting participation rates, but as brokers usually vote in line with management (Gulinello 2010), may be counter to the thoughtful ESG voting required in responsible investment , and does not link investors’ ESG views to their ownership rights.

4.2.3 Discount Brokerage

In 1975, the Securities and Exchange Commission deregulated commissions (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 1975), which together with technological and communications advances that fostered cost-efficient trading platforms, led to the advent of the discount brokerage channel. Discount brokerage firms do not offer client-specific advice and essentially offer trade execution, settlement, and custody of investments for a low price, usually through an on-line platform rather than personal contact. Because investors conduct their own research and determine for themselves the suitability of an investment, the obligations from the discount brokerage firm are lower (and less costly) than they would be for a full-service brokerage firm. Proxies are delivered directly to investors and, consistent with the level of economic advice, no advice is given on how to vote.

4.2.4 Portfolio Management

If discount brokerage is a stripped-down provision of direct access to the stock market, portfolio management is a step up in service, advice, and responsibility from full-service brokerage. As noted above, portfolio managers have a statutory ‘fiduciary’ obligation to clients rather than the ‘suitability’ obligation that applies to brokerage relationships. Portfolio managers work with clients to establish overall financial objectives and then invest on their behalf in portfolios of securities—usually leveraging sophisticated platforms to diversify amongst a larger number of investments than a typical brokerage account.

Portfolio management was historically offered to larger institutions such as endowments, pension plans, and ultra-wealthy individuals by dedicated portfolio managers. In the past, if a portfolio manager wished to offer its investment expertise to a retail investor, it was usually done via a mutual fund accessed through a third party (such as a broker or financial planner). Just as technology allowed discount brokers to offer new management services to retail investors , portfolio managers were also able to offer discretionary management of individual securities at lower asset levels, which meant that retail investors were now served by two groups with different origins.

Regardless of their firm origin, US portfolio managers are required to vote proxies. Canadian retail clients may delegate proxy voting to their portfolio manager, but the administrative infrastructure does not support this well, nor is there a regulatory requirement for the manager to actually vote (Canadian Securities Administrators 2013). Many retail clients will therefore still receive proxies for stocks selected by their portfolio manager.

4.3 The Proxy System

The important distinction amongst the three types of retail delivery channels is in the level of service and advice and in the level or type of responsibility owed to the client. In all three brokerage channels, though, the retail client remains the beneficial owner of the securities. Brokerage clients (full-service and discount) receive proxies in their mailbox or inbox. Portfolio managers are required to vote proxies on behalf of retail clients in the US but not in Canada.

The proxy system is complex, with more than a dozen participants engaged in over fifty activities (Shareholder Communications Coalition 2017). The core function is the delivery of notice and materials for corporate meetings and, since most shareholders are not able to attend in person, proxies for the casting of their votes. Voting is a key obligation under the Principles of Responsible Investment , and proxies may include shareholder initiatives aimed at particular ESG concerns (UNPRI 2017). In contrast to institutional practices, retail shareholders’ inability to vote their proxies effectively is a significant gap in the effectiveness of responsible investment.

Several shareholder choices impact the system, including the way shares are held, and whether the shareholder has agreed to disclose their contact information to the corporation.

4.3.1 Registered or Street Form?

Each corporation sets a ‘record date’ for which shareholders will be entitled to receive proxies and vote in a corporate meeting. To focus on their own business activities, corporations usually contract shareholder record keeping duties to an independent transfer agent (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2015a).

Shareholders who are registered directly—for example, if they have a physical certificate or if they have taken an extra step to have their shares registered directly with the transfer agent—will have their meeting materials and proxies sent directly to their registered address. While this system was very common before the SEC reforms in the 1970s, the ‘vast majority’ of investors hold their shares in ‘street form’, or electronically, at a centralised depository—Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC) (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2015a). A record of each shareholder’s investments is maintained by the brokerage, but the shares themselves are held and registered collectively (i.e. all clients together) at the depository. DTCC is the registered owner, the brokerage firm is the intermediary, and the investor is the beneficial owner.

4.3.2 The OBO/NOBO Distinction

When opening a brokerage account, each investor chooses whether to Object to disclosure of their Beneficial Ownership (OBO) or Not to Object to disclosure of their Beneficial Ownership (NOBO) to the companies in which they invest. Just as corporations use a transfer agent, brokerage firms usually contract out proxy voting duties to a specialist firm (usually Broadridge).

Most investors choose not to disclose their contact information, so companies are not able to send them information directly, but rather must rely on the brokerage firm (intermediary) to relay it. It is due to their roles as intermediaries that brokers can vote on routine proxy matters even if they have not received instructions from their client.

When reviewing their shareholder lists with their transfer agent, issuing corporations will see the contact information for all NOBOs, but for OBOs’ would see just the combined shareholdings and the name of an intermediary (brokerage firm). Noting how the proxy system dissociates investors from their ownership rights, the Shareholder Communications Coalition wrote to the SEC regarding the current OBO/NOBO system:

There are no standards or regulatory requirements for how a broker-dealer or bank reviews this classification with its customers at account opening, or on a periodic basis to ascertain if a customer’s preferences have changed. The NOBO/OBO classification is also not established on a company-by-company basis, and many investors – especially individual investors – do not even know how they have been categorized. The NOBO/OBO system impedes communications between shareholders and public companies and also creates barriers to communications among shareholders themselves. NOBOs also represent only a portion of a company’s shareholder base (Shareholder Communications Coalition 2016, pp. 3–4).

4.3.3 Notice-and-Access

Cross-border securities trading and settlement between the United States and Canada is common so administrative procedures are often reviewed contemporaneously. Both countries have moved to ‘Notice-and-Access’ protocols whereby beneficial owners are sent notice of a meeting along with instructions about how to access meeting materials (usually electronically) and to vote (Canadian Securities Administrators 2012b; U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2007). The notice-and-access system follows the communication chains prescribed by form of shareholding (registered or street) as well as OBO/NOBO elections and allows companies to send different forms of information and instruction to different groups. The new protocol saves printing and postage costs but relies further on retail investors seeking the information required to vote their proxies responsibly.

4.3.4 Proxy Voting Trends

Figure 8.4 shows that in 1976 almost 70% of retail shareholders always voted, and an additional 23% sometimes voted their proxiesFootnote 6 (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 1976). These data points are extrapolated to show the decline in voting participation between then and now (2008–2015 data) (Broadridge 2015).Footnote 7 The trend line supports the recommendation that regulators should focus more on reversing the secular decline than on fine-tuning the mechanics of the proxy system. Retail investors will not be engaged in responsible investment if the current trend isn’t reversed.

An explanation for the decline—that retail shareholders, unlike their institutional counterparts, have been persistently dissociated from their ownership rights since the mid-1970s—is offered below. The continued dissociation entrenches further the third stage of capitalism in the pentagonal model and highlights the challenge remaining in stage four: the re-engagement of retail investors in responsible investment . If retail investors don’t vote at all, an important voice in responsible investment is left silent.

5 Stages of Capitalism: The Pentagonal Model

Both the four-stage and five-stage linear models presented earlier are incomplete. The four-stage model is not descriptive of capitalism but rather just the various ways in which investors supply their capital for economic gain. The linear form is consistent with the shift in analytical tone regarding agency issue s between Berle (1920s) and Jensen and Meckling (1970s), in which ownership rights became secondary to economic rights, despite their centuries long co-development. In the four-stage model, ownership rights disappear after stage two.

Clark and Hebb (2004) in their five-stage model focus on the re-integration of ownership rights, but the linear model can be modified to demonstrate better the re-connection. The new pentagonal or house shape highlights the importance of responsible investment and shows the challenges that remain for retail investors investing directly through brokerage firms. The new model emphasizes processes or concepts related to property rights —economic and ownership—rather than the linear model’s heavier reliance on institutional form. Note that the pentagonal model combines the original stages three and four (both relate to intermediaries) so the model again includes just four stages.Footnote 8

5.1 Dissociation (Stage Three)

Recall that the first stage of capitalism is represented by entrepreneurs , or owner-operators, who reached their Robber Baron zenith in the Gilded Age, but who continue today in smaller companies. The second stage is distinguished by the separation of ownership and control and the introduction of an agency issue . Major owners are large and resourceful but are at an informational disadvantage compared to the full-time business managers. In the third stage, retail owners have been further dissociated. They invest smaller amounts of capital and are at an even greater informational disadvantage. Financial intermediaries separate minority (retail) investors from corporations, though their property rights remain strong (La Porta et al. 1999). Several additional factors have further dissociated retail investors from their ownership rights, but these rights have not yet received the same level of protection as have economic rights. Without better protection from regulators, responsible investment will remain inaccessible to retail investors.

5.1.1 Dematerialization

The steady growth of stock exchange trading volumes combined with the manual process of registering, printing, and delivering stock certificates to owners led to “the distressing events of 1968–1971 when an unexpected surge in trading volume caused the securities industry to almost drown in a sea of paperwork” (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 1975, p. 2). An unwelcome downturn in markets at that time led to a crisis of paperwork and confidence and to three substantive reforms: the establishment of a central depository for shares, the imposition of net settlement of trades at the end of the trading day, and shifting to electronic or ‘street form’ holdings of shares instead of physical share certificates, a process called dematerialization (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2015a).

The reforms were an effective response but dealt only with the economic rights of share ownership. The SEC considered the broader impact of dematerialization but reasoned it had no other practical option (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 1976). Proxies and annual reports continued to be delivered by mail. Dematerialization dissociated shareholders from the tangible aspects of ownership they had enjoyed in the United States since the 1700s—the physical share certificate (Donald 2007; U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2015a).Footnote 9 The implementation of stock dematerialization mirrors the decline in proxy voting shown in Fig. 8.4.

5.1.2 Proxy System Reforms: Notice-and-Access

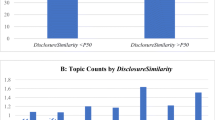

Figure 8.5 shows investors who receive full proxy packages are much more likely to vote than are those who receive an electronic package or a notice-and-access letter. The significant decrease in information sent to retail investors correlates with an immediate and noticeable decline in retail voter response (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2008b).

Retail positions voted by delivery method (Source: Broadridge (2015))

Declining voter turnout in general elections has been linked to voters’ ages (Blais and Rubenson 2013), and is a plausible explanation here, as older voters may be more likely to request a full package over electronic delivery. An alternate explanation, also based on election research, is that receipt in the mail of a full package reinforces an ownership connection with the company and an obligation to vote as part of a social norm (Gerber et al. 2008). The social norm explanation is consistent with the high proxy voting rates in 1976 shown in Fig. 8.3, before the dematerialization of physical share certificates.

Figure 8.6 shows the number of shares voted, rather than the number of shareholders (positions). The number of shareholders voting their proxies is considerably lower than the number of shares voted, indicating that small shareholders are less likely to vote. Two possible explanations are that larger (wealthier) shareholders are more likely to be served by portfolio managers, who as fiduciaries vote their proxies, or that smaller shareholders may be more inclined to ‘free ride’, as “it is simply not worthwhile … to acquire information so as to vote” (Downs 1957, p. 147).

Retail shares voted by delivery method (Source: Broadridge (2015))

Retail investors ’ dissociation from their proxy rights is evident and most pronounced amongst smaller shareholders and those receiving notice rather than a mailed package. Though the pentagonal model of capitalism diagram is symmetrical, retail investors at the third stage vary in their separation from the business managers in the top left, depending upon their level of dissociation. Regulators should take note that it is heading in the wrong direction.

5.1.3 Behavioural Finance

Behavioural research has contributed much to finance and offers explanations of many retail investor actions. A 1975 study showed that subjects who chose a lottery ticket themselves attached a much higher value to it than did those who were assigned a ticket. Though the economic value was identical in each case, participants felt a sense of ownership and control over the outcome when they participated in the process (Langer 1975). Portfolio managers choose stocks for retail clients, resulting in greater dissociation compared to investors who choose stocks themselves at a discount brokerage. Advice from a broker on a suitable stock would fall between the two.

Investors have been similarly dissociated by an increase in the number of stocks in their portfolios. Brokerage firms have used technology and mass customization to efficiently recommend and track a larger number of stocks. As a result, the stock positions in a brokerage client’s portfolio are often smaller, more numerous, and less familiar to them.

The short-term focus of market participants has been suggested to be the self-reinforcing activities of two groups: business leaders, who publicly set short-term earnings targets and then manage results to meet those goals; and investors who are attracted to the short-term results (Brochet et al. 2012). Both business leaders and investors may be predisposed to short-term focus (Clark 2011); the former may be incented financially, while the latter may be responding to behavioural issues such as overconfidence (Barber and Odean 2000) or to a weaker ownership connection.

Diminished participation in the stock selection process, increased diversification, and shorter holding periods may combine as both cause and symptom of dissociation, resulting in a lower propensity to vote proxies. Behavioural research supports the concept that portfolio managers who choose stocks should also vote proxiesFootnote 10 and questions the asymmetry between brokers’ provision of stock but not proxy advice.

5.1.4 Globalization and Neoliberalism

Ownership rights were first dissociated in the Victorian era by the establishment of the corporation as a ‘natural person’ with inherent rights, the dissociation of minority shareholders’ rights through plutocratic voting, and the geographic distribution of ownership via stock exchanges. Since that time, corporations have grown in scale and geographic reach. The export-led growth of the Golden Era was followed by foreign branch plants and then multi-national operations in the Neoliberal Era (Harvey 2005), which increased the geographic separation of shareholders from corporate head offices (Westbrook 2015). What in the past had been local—good for both General Motors and America—became more complicated; the connection to corporate operations had become connection to a brand.

Retail investors ’ affinity for a company is often based on proximity and familiarity (brand) (Barber and Odean 2008), similar to the process described below for values-based investing. Based upon the increase in stock trading frequency (Barber and Odean 2011) and declining proxy voting rates, retail investors are less inclined to voice dissatisfaction via their proxies than by selling (or not purchasing) a stock.

The multi-national scope of corporations, their size relative to many nation-states, and their transformation into brands raises questions about the original social contract between individuals and the state. Mercantilist corporations of the 1600s such as the Dutch East India Company were also large with expansive operations, but they were creations of the state—charter companies—with a democratic shareholder membership. Because retail shareholders seldom vote their proxies, they are unable to ensure corporate citizens respect their role within the social contract.

Neoliberalism “has pervasive effects on ways of thought to the point where it has become incorporated into the common-sense way many of us interpret, live in, and understand the world” (Harvey 2005, p. 2). Ironically, while it “emphasizes the significance of contractual relations in the marketplace” (Harvey 2005, p. 2), it relies on corporate supremacy and relegates small (retail) shareholders to the provision of capital—and as demonstrated by the low proxy voting levels—with little accommodation for or interest in their ownership rights.

One of the governance issues addressed by responsible investment is executive pay, which has contributed to wealth inequality and to a socio-economic gap in which corporate elites gather globally at events such as the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland to exchange ideas (Harvey 2005; Picketty 2014). The gap is also one of power—a version of the labour/capital struggle (Kotz 2015). Retail investors have less in common with corporate leaders and feel less connected to the companies in which they invest, and their dissociation contributes to a lowering of expectations regarding the efficacy of their proxy voting.

5.1.5 Summary

The evolution from stage two to three is more than the introduction of portfolio managers as intermediaries. Retail investors have been dissociated from their stocks because of discrete actions such as the dematerialization of physical share certificates (and introduction of summary paper and then on-line statements) and by the imbalances caused by Neoliberalism. Though the pentagonal diagram is presented symmetrically, the distance between stage two and three is dependent upon the number of economic (portfolio manager) intermediaries and upon the variable impacts of ownership (proxy voting) dissociation.

The three investment channels—portfolio manager, broker, and discount broker—are notable for the different gaps they generate. They dissociate investors to different degrees, but also offer opportunities to reconnect retail ownership rights through responsible investment , completing the fourth stage of the pentagonal model that was started by pension managers and more recently incorporated by portfolio managers serving retail clients.

5.2 Responsible Investment (Stage Four)

5.2.1 History

Responsible Investment is a broad term encompassing several areas. In the nineteenth century, “groups of mostly Christian investors began screening their investments for activities they considered sinful,” and in 1928 the first fund using similar values screens became available to investors (Knoll 2010, p. 684). Values-based negative screening gained popularity, including efforts to avoid military contractors during the Vietnam War, companies conducting business in South Africa during apartheid, and more recently to avoid fossil fuel companies. Values-based investing—often referred to as Socially Responsible Investing or SRI—may also involve positive screening, focussing on companies producing positive social outcomes (e.g. solar power) or those which meet higher social standards. In both negative and positive screening, the focus is on investment returns and not on active ownership or proxy voting.

A recent further step along the values chain has been the development of impact investing, which combines the twin goals of an investment return and a social impact. Though it re-integrates economic and ownership rights, it is not usually part of retail investors ’ participation in the broad public markets.

5.2.2 The Ownership Voice

With their large, illiquid holdings, and their fiduciary obligations to optimize returns and reduce risk over long timeframes, pension funds and other institutional investors are hampered in using values-based screens to exit investments. Instead, wrote Albert Hirschman in 1970, they are advised to use their voice “to change rather than to escape from an objectionable state of affairs” (Hirschmann 1970, p. 30). The use of voice through direct engagement and proxy voting is consistent with the more recent concept of a universal owner, in which the externalities of one firm impact the operations and profitability of others, rendering divestment ineffective both economically and with respect to ESG . Divestment leaves externalities unaddressed and results in the portfolio’s underperformance (Monks and Minow 2011); nonetheless, it is still the primary method by which retail investors holding individual stocks act on their ESG concerns. Several studies show investment outperformance over benchmark indices for responsible investment strategies broadly (Clark and Viehs 2014; Nagy et al. 2015) and for corporate engagement specifically (Dimson et al. 2015).

The adoption of responsible investment by institutional investors overlaps with the growing awareness of environmental issues, popularized by Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring and more recently the issue of climate change . It also coincides with the decline of the Golden Era’s regulated capitalism and the subsequent rise of inequality under Neoliberalism. Although the aim of responsible investment is to enhance economic outcomes by advancing social ESG norms, it may also be viewed as a response to the macro aspects of Neoliberalism and globalization. For example, global expansion has allowed companies to use labour or environmental practices that would be unacceptable in their home jurisdictions, prompting institutional investor response.

Figure 8.7 shows the recent increase in responsible investment assets in several jurisdictions. It includes institutional assets (e.g. pension funds) as well as retail investments such as mutual funds. It does not include stocks held directly by retail shareholders but is consistent with another recent survey of that group and does indicate a broad level of interest in responsible investment. When combined with the proxy voting data from Fig. 8.4, the data highlight the gap between retail investors ’ interest in ESG issues and the efficacy of the proxy voting system in support of that interest if they invest directly in stocks. The voice of pension funds, endowments, and other stage-four investors is organized, funded, and articulate, but it is dwarfed by the tens of millions of retail investors who own stock directly and who can provide the social momentum necessary for change noted by Kotz (2015). The voice of retail investors who own stocks directly is quiet but offers tremendous support to the institutions that have led the way so far in responsible investing and the fourth stage of capitalism.

Responsible investment managed assets—level and trend by region (Source: Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (2015))

Figure 8.7 shows large differences amongst countries. This may be due to several factors, including differences in: regulatory and institutional support, demand levels, and models of capitalism (European welfare liberalism versus US Neoliberalism), and could be investigated in a separate paper, perhaps correlating responsible investment with types of capitalism.

5.2.3 Reintegration of Ownership Rights

Active ownership emerged through institutional investors , in particular pension funds, which first engaged companies in aspects of governance to address agency issue s and transparency , and later incorporated environmental and social issues into their dialogue and proxy voting in order to mitigate long-term ownership risks (Clark and Hebb 2004). The integration of ESG issues into corporate engagement and proxy voting provided a new framework for the analysis and selection of suitable investments and was distinguished from the values-based screening embraced by retail investors by the reclamation of ownership control over corporate behaviour. The United Nations backed Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI ) provided legitimacy and promulgated a framework that asset owners, investment managers, and industry could adopt, but other than an educational module, they do not yet include the retail investor channel.

The pentagonal model shows dissociation as the third stage of capitalism and the reconnection of ownership rights through active proxy voting as the fourth—the link that reconnects the ownership rights back to the business manager. The agency issue identified by Berle between the business owner and the business manager is central to the second stage and is shown as a red curved line in the diagram. There exists a similar agency issue between portfolio managers and business managers, which in stage four is represented by the same red arc in Fig. 8.8.

Notice that the fourth stage includes only one retail investment channel, so while the outside lines are now connected (major investors , portfolio managers), two brokerage channels (green dotted lines) remain unconnected. In Canada, all three brokerage channels are unconnected, which enforces the importance of regulatory clarity and action. Statutory fiduciary obligations would be appropriate for Canadian portfolio managers and should be considered for brokers in both countries, but this would be inappropriate for discount firms.

6 Recommendations

Kotz draws a pattern in the ebb and flow of types of capitalism, with inflection periods after economic crises or stagnation and extremes in wealth inequality—an observation supported by Picketty’s centuries long time-series data (Kotz 2015; Picketty 2014). Appraising property rights , the corporate form, and stock markets over a similar time frame situates the rise of responsible investment as the start of a fourth stage of capitalism. To capitalize on Kotz’s inflection point, it still requires popular support, part of which can come from the broad base or retail shareholders.

With over one half of stocks in the United States owned by retail investors , and with the data showing their interest in responsible investment , re-establishment of effective ownership rights should not only lead to positive ESG outcomes and improved investment performance but also help embed responsible investment within the next era of capitalism. The catalyst for broader ESG engagement should be reappraisal of the proxy system for retail investors , for “the very vitality of the capital markets depends so heavily upon informed and knowledgeable communications” (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 1971, p. 1). Institutional investors have been important leaders in this regard, using their proxies and direct engagement to change corporate behaviour. Despite their large ownership stake and proxy voting power, they are small in number and work within the existing system rather than advocating for systemic change. Institutional investors have the resources to work within the current system, but retail investors have neither the resources nor incentive to self-organize.

“Unless the number of individuals in a group is quite small, or unless there is coercion or some other special device to make individuals act in their common interest, rational, self-interested individuals will not act to achieve their common group interests” (Olson 1971, p. 1). The effort required for individual investors to become informed about each issue for each stock they own is an insurmountable challenge. Regardless of how smooth or finely tuned the proxy system becomes—though regulators and practitioners should continue to work to this end—retail investors will neither vote directly nor organize collectively to produce a solution. The solution rests primarily with regulators, who will require support from industry participants, corporations, and not-for-profits interested in issues of governance or responsible investment .

The proxy system is under review by the SEC and Canada’s securities regulators, but their indicated approaches do not address the broader, systemic issue of the secular decline in retail investor proxy voting shown in Fig. 8.4. They should continue to address the inefficiencies in the system—important goals to be sure—but if they leave unaddressed the broader issue of engaging retail investors , responsible investment will not reach the full promise of embedding ESG factors in capitalism and society. Instead, like the use of colourful envelopes cited earlier, the changes will produce benefits at the margin. Regulators should seek transformative change in the following three ways.

6.1 Fiduciary Duty (Part II)

The ERISA legislation in 1974 established the requirement for corporate pension and employee benefit plan managers to act as fiduciaries, including the voting of proxies (U.S. Department of Labor 2008). Portfolio Managers not governed by ERISA will in any case be regulated by the SEC (in some cases delegated to the state), which similarly requires them to vote proxies on clients’ behalf (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2003). The Department of Labor’s proposed (now paused) new rules would have required all investment professionals offering advice on individual retirement plans such as IRAs and 401(k)s to be considered as fiduciaries. They are primarily intended to address potential conflicts of interest and are silent with respect to proxy voting, but might be expected to evolve to include provisions in the future, thereby nudging the retail operations of FINRA regulated brokers to a more effective proxy system. The prospective changes would apply only to individual retirement plans and not taxable accounts, but any changes to the proxy voting architecture for the former could easily work with the latter; an individual client often has both retirement and taxable accounts with the same broker. Discount brokerage firms are unlikely to be included as fiduciaries, but other potential measures are possible.

The distinction between fiduciary and non-fiduciary roles and accounts may still be unclear to many retail investors , but each step towards common requirements is helpful. The regulatory goal should be similar levels of responsibility for economic rights and ownership rights, commensurate with the level of service and advice in each of the three retail channels described earlier.

In addition to regulatory change, CFA charterholders could be required to vote proxies as part of their duty to serve clients’ best interests (CFA Institute 2014), in particular if the duty is linked to evidence of better investment performance. Like the conclusions reached earlier by many ERISA pension funds, a 2015 study found that responsible investment itself was a fiduciary duty —that incorporation of ESG factors in to the selection of stocks and in the voting of proxies was obligatory (Sullivan 2015). The study’s findings support the recommendations made here to both regulators and CFA Institute.

6.2 The Client Account Form

The proposed regulatory and professional organization changes are based on broad principles (i.e. fiduciary duty ). Administrative changes may also be effective. For example, when opening a brokerage account, acknowledgment of the level of investment risk an investor is willing to assume (low, medium, high) is required. A similar question regarding ownership rights (i.e. proxy voting) could also be asked regarding an investor’s interest in responsible investment .

While ensuring investment recommendations are suitable to the stated level of risk, the individual stocks in an account may differ amongst brokers, but their selection will be based upon common principles of risk (e.g. size, liquidity, earnings stability , and growth). Ideas regarding responsible investment , including proxy voting, will also differ amongst brokers and investors , but they too will be based upon common ESG principles.

Regulatory changes in 2009 to brokers’ ability to vote proxies without clients’ instruction prompted the suggestion that brokers receive blanket instructions up front, so they may vote accordingly on clients’ behalf (Beller et al. 2010). While the suggestion was not linked to responsible investment , blanket guidance could easily incorporate questions about responsible investment.

6.3 Client Account On-line Access

ERISA required fiduciaries to make available proxy voting procedures and records of past votes, and while the Department of Labor doesn’t specify how, many larger organizations provide it on-line (U.S. Department of Labor 2008). Some take the additional step of sharing in advance how they intend to vote, which can be helpful to discount brokerage investors who conduct their own research. Market participants may wish to consider how publicly available proxy guidance could be aggregated and summarized for ease of use by these investors.

Most brokerage firms offer on-line access so clients can view their investment holdings and transactions. This should be expanded to include proxy voting. Information of upcoming votes and past voting records should be included. Many brokerage firms use Broadridge for both investment record keeping and proxy voting, but despite Broadridge’s significant work in on-line proxy voting platforms, the two systems have evolved differently and are accessed separately. Work would be required to bring them together. In a letter to Canada’s regulator regarding the distribution of mutual fund reports to investors , Broadridge commented about “the convenience to investors of accessing fund reports at one familiar site for all positions held rather than accessing each of the reports at a different fund company site” (Broadridge 2015, p. 21), which supports in principle the centralized proxy viewing system suggested here.

Blockchain, a promising new technology best known for its Bitcoin application, may offer help in this regard. Blockchain is a new system of record keeping in which records of ownership are maintained by a distributed network rather than central corporate servers. Many participants in the capital markets, including stock exchanges, regulators, financial intermediaries, and market participants, are exploring its use, which could include reintegrating the economic and ownership rights of investors .

7 Concluding Remarks

The governance issues within corporations and stock markets are complex, and retail investor proxy voting is just one of many items to be addressed. Regulators must also grapple with the independence of proxy advisory firms’ advice, the effect of monopolist firms such as Broadridge, the structure and election process of corporate boards, policies for shareholder proposals, and whether issuing corporations want to engage their retail shareholder base (some may not like the feedback they receive).

While property rights developed over many centuries, corporations and modern capitalism are relative latecomers. We should strive for a more inclusive system—for its own sake, because property rights are important and because it offers the promise of a better future—but we should not be disheartened if it takes time.

The different eras of capitalism must have seemed so promising at first and then so terrible when they petered out (1970s) or collapsed (1929), but they gave way to reflection on the social contract and, as Kotz describes, to popular support for the next era. Writing about the early European securities markets, Michie notes that their evolution was not dictated by government or “the needs of any particular regime” but rather by the broader demands of trade and finance (Michie 2007, p. 27). Today, it is the demands of responsible investment —the need to address the negative externalities of corporate capitalism while still enjoying the very many benefits it has produced—that impel changes to the retail proxy voting system.

Broad support for responsible investment can be significantly enhanced by engaging the democratic base of retail shareholders. Large institutional investors and portfolio managers enjoy the plutocratic voting power of their shareholdings and are lauded for their role in addressing ESG issues, but they are not substitutes for popular support. If they truly believe in the substance of their ESG corporate engagement, they should also advocate to regulators and government for systemic change to complete the fourth stage of capitalism that they so capably began.

Notes

- 1.

While corporations may issue multiple, subordinated, or non-voting shares, it is assumed here that each share is entitled to one vote.

- 2.

Writing a century earlier, Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations identified agency issue s as well, but Berle’s work is more contextual to the public corporation and liberal capitalism.

- 3.

The actual figure will be higher than 14% as retirement accounts and managed assets, which may also hold directly owned stock, are not included.

- 4.

Including personal retirement accounts but excluding defined benefit plans.

- 5.

Portfolio manager is a generic term describing the function. The regulatory terms for the positions are Registered Investment Adviser (RIA) for the firm and Investment Adviser Representative for the individual. Both firm and individual are usually called RIAs.

- 6.

The survey had a 24% response rate (23,600 out of 97,100 questionnaires). Respondents identified as individuals (21,143), institutions including trusts and estates (2263), and no response (189). Proxy voting behaviour: always (16,467), sometimes (5463), never (1417), and no response (253).

- 7.

Some care should be taken interpreting the data as the SEC and Broadridge methodologies are different and they may also use different definitions of ‘retail investor.’ Broadridge also publishes an annual report (Broadridge 2016) which shows a 28% participation rate. The lower figures used in the graph are consistent with my professional experience, but either set of figures would represent a significant decline from the 1976 SEC data.

- 8.

Though there is some overlap, the four stages of capitalism should not be confused with the alternating eras of regulated and liberal capitalism described by Kotz (2015).

- 9.

In my early days in the investment business in the 1990s, I encountered many investors who had purchased their shares many years prior and who—despite the extra risk and work involved in keeping their certificates safe and in depositing quarterly dividend cheques—were loath to deposit their certificates into street form. They valued the physical ownership, much as many today still retain their old record albums or CDs despite the availability of subscription digital music services.

- 10.

The behavioural research also highlights again the gap in Canada between the portfolio manager’s selection of stock but lack of proxy voting obligation.

References

Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2000). Trading is hazardous to your wealth: The common stock investment performance of individual investors. Journal of Finance, LV(2), 773–806.

Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2008). All that glitters: The effect of attention and news on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. The Review of Financial Studies, 21(2), 785–818. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhm079

Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2011). The behavior of individual investors. Social Sciences Research Network, 1–54. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1872211

Baumol, W. J., Litan, R. E., & Schramm, C. J. (2007). Good capitalism, bad capitalism, and the economics of growth and prosperity (On-line). New Haven/London: Yale University Press. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=985843

Bebchuk, L. A., & Fried, J. M. (2003). Executive compensation as an agency problem. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(3), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533003769204362

Beller, A. L., Fisher, J. L., & Tabb, R. M. (2010). Client directed voting: Selected issues and design perspectives. Retrieved from http://www.cii.org/files/publications/white_papers/08_31_10_client_directed_voting_white_paper.pdf

Berle, A. A. (1928). Studies in the law of corporation finance. Chicago: Callaghan and Company. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2007.54.1.23

Blais, A., & Rubenson, D. (2013). The source of turnout decline: New values or new contexts? Comparative Political Studies, 46(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414012453032

Bratton, W. W., & Wachter, M. L. (2008). Shareholder primacy’s corporatist origins: Adolf Berle and the modern corporation. Journal of Corporation Law, 34(1), 99–152.

Broadridge. (2015). Letter from Charles V. Callan to Brent J. Fields. Comments on proposed rule 30e-3, investment company reporting modernization, file number S7-08-15. Broadridge. Retrieved from https://www.sec.gov/comments/s7-08-15/s70815-321.pdf

Broadridge. (2016). Proxy pulse: 2016 proxy season review (3rd ed.). Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions, Inc.

Brochet, F., Serafeim, G., & Loumioti, M. (2012). Short-termism: Don’t blame investors. Harvard Business Review, 90(6), 28.

Canadian Securities Administrators. (2012a). CSA consultation paper 33-403 – The standard of conduct for advisers and dealers: Exploring the appropriateness of introducing a statutory best interest duty when advice is provided to retail clients. Ontario Securities Commission. Retrieved from http://www.osc.gov.on.ca/documents/en/Securities-Category3/csa_20121025_33-403_fiduciary-duty.pdf

Canadian Securities Administrators. (2012b). CSA notice of amendments to national instrument 54-101 communication with beneficial owners of securities of a reporting issuer and companion policy 54-101CP communication with beneficial owners of securities of a reporting issuer and amendments to nation. Ontario Securities Commission. Retrieved from http://www.osc.gov.on.ca/documents/en/Securities-Category5/csa_20121129_54-101_amendments.pdf

Canadian Securities Administrators. (2013). CSA consultation paper 54-401: Review of the proxy voting infrastructure. Ontario Securities Commission. Retrieved from http://www.osc.gov.on.ca/documents/en/Securities-Category5/csa_20130815_54-401_proxy-voting.pdf

CFA Institute. (2014). Code of ethics and standards of professional conduct. CFA Institute.

Clark, R. C. (1981). The four stages of capitalism: Reflections on investment management treatises reviewed work(s): The regulation of money managers by Tamar Frankel; the law of investment management by Harvey E. Bines. Harvard Law Review, 94(3), 561–582. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1340677

Clark, G. L. (2011). Myopia and the global financial crisis: Context-specific reasoning, market structure, and institutional governance. Dialogues in Human Geography, 1(1), 4–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820610386318