Abstract

Well-being is vital to the success of military operations and the health of service members and their families. We conceptualize well-being as multidimensional and define it as an ongoing integration process of dimensions (the level of happiness, meaning, and/or satisfaction) within the three domains of Work, Life, and Work–Life. This chapter examines well-being in military service members and their families, and suggests that well-being can be conceptualized using the aforementioned domains, which were developed earlier as part of the Work–Life Well-Being Inventory. These dimensions were developed through focus groups with soldiers, additional research conducted on well-being, and literature reviews. The leader and organization supporting the family dimension was the only dimension theoretically derived for this model. The 19 dimensions that influence well-being are divided into three domains. These dimensions outline the positive functioning of individuals, as opposed to focusing on negative functioning. In what follows, we describe the dimensions in each well-being domain and discuss the relevant supporting literature. Based on this literature, we provide recommendations for providers, educators, and leaders to enhance the well-being of military members and families. We also suggest self-management approaches that can help service members preserve and increase their well-being.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Leader

- Self-management

- Unit trainer/educator

- Military psychology

- Provider

- Well-being

- Service member

- Life well-being

- Work well-being

- Work–Life well-being

Well-being is vital to the success of military operations and to the health and fitness of service members and their families. The armed forces demand a physical and emotional capacity from service members that is distinct from other occupations. Service members receive extensive physical and mental training before being employed to assure that they can successfully contribute to operations. Even with this training, service members and their families face unique threats to well-being. Some of the most important distinctions between military personnel and their civilian counterparts involve the stress associated with deployments, extended periods away from home, additional workload (deployed service members’ duties) while in Garrison, and frequent moves. For service members, stressors include combat exposure, deployments, and poor marital quality, all of which can impact well-being (MHAT-9). For spouses, factors that negatively impact well-being include moving to and living in foreign residences, family separations, and the risk of service member death or injury (Burrell, Adams, Durand, & Castro, 2006). We have organized these stressors into three domains of well-being. On conceptual grounds, we categorize well-being into three broad domains (Work, Life, and Work–Life overlap), under which 19 dimensions are subsumed. Stressors in the Work domain for well-being are risk of injury or death, negative leadership, repeated deployments, and/or separations from family. Stressful demands in the Life domain are partner violence, divorce, and financial difficulties. Demands in the Work–Life domain are work–family conflict, household moves, post-deployment reintegration, and psychological and physical combat injuries. In this chapter, we describe the three domains and identify the 19 dimensions that compose service member well-being. Additionally, we provide recommendations for five resources that can mitigate demands of the service member.

The Work dimensions of well-being include positive work environment and positive leader support, coworker support, trust in the leader and organization, negative supervision, job stress, realistic work demands, motivation, and job satisfaction. Life dimensions of well-being include friendship support, satisfaction with medical services, personal development, marital strength and family support, financial stability, and satisfaction in community. The Work–Life domain includes general well-being factors that cross over the Work and Life domains to include: emotional well-being; satisfaction with work, family, and leisure time; personal development; healthy habits; spirituality; leader and organization supporting the family; and community family support. This three-domain model delineates the well-being dimensions that can enrich the lives of service members. The five resources that can mitigate stressful demands and buffer against threats for service member are: the service member, the service member’s family, various care providers (e.g., behavioral health provider, primary care practitioners, chaplain), trainer-educators, and leaders who educate and/or coach service members and their families. Each of these resources provides a critical role in helping the service member maximize well-being and reap specific adaptive outcomes. Figure 14.1 provides a visual depiction of the demands, resources, well-being domains, and adaptive outcome for the service member. Within this framework, the dimensions of well-being can also at times be resources or demands.

Well-being is critical for high-demand occupations like the military. Other high-demand occupations in the government and public sector, including federal intelligence agencies, police and firefighters, emergency medical services, and industry sectors, face some similar demands, challenges, and limitations. Service members and workers in high-demand occupations are routinely involved in complicated, time-consuming, and dangerous around-the-clock operations that are inherently stressful and can significantly impact well-being. Moreover, military personnel can be required to relocate to remote locations, may be restricted in the ability to resign from their positions, and are prevented from joining unions that negotiate in favor of their workplace rights. Due to the high-risk nature of military operations in both peacetime and wartime, it is of special importance that providers, leaders, and other sources of support understand how best to promote well-being in service members and their families.

Well-Being: History, Definitions, and Dimensions

There is no consensual definition for well-being. As a construct, well-being overlaps with quality of life and wellness. Well-being has historically been approached in two distinct ways (Bates & Bowles, 2011). In the hedonic tradition, well-being is identified primarily with pleasure, happiness, and satisfaction in life. In contrast, the eudemonic approach associates well-being with the pursuit and realization of purpose and meaning in life (Dodge, Daly, Huyton, & Sanders, 2012). Although the two approaches appear separate, they both involve an interrelated process wherein feelings and thinking reciprocally affect one another and influence how people react in certain situations (Moore, Bates, Brierley-Bowers, Taaffe, & Clymer, 2012). Dodge and colleagues (2012) note that several researchers now believe well-being is multidimensional. Gallup researchers describe well-being as

. . . the combination of our love for what we do each day, the quality of our relationships (career and social well-being), the security of our finances, the vibrancy of our physical health, and the pride we take in what we have contributed to our communities. Most importantly, it’s about how these five elements interact. (Rath & Harter, 2010, p. 4).

Rath and Harter’s dimensions of well-being are also found in the well-being military model. Similarly, this multidimensional approach is found in Seligman’s book, Flourish , in which he identifies five dimensions of well-being that include positive emotion, engagement, meaning, accomplishment/achievement, and positive relationships (2011). The military well-being model dimensions listed in parentheses are next to Seligman’s five dimensions and can be found or inferred for the well-being model elements of positive emotion (emotional well-being), engagement (motivation and job satisfaction, trust in leadership), meaning (personal development), accomplishment/achievement (motivation and job satisfaction, healthy habits), and positive relationships (martial and family strength, friendship, coworkers, trust in leadership).

We define well-being as an ongoing integration process of the level of happiness, meaning, and/or satisfaction experienced in the dimension(s) of life and/or work being engaged (Bowles, 2014). This chapter examines well-being in military service members and their families, and suggests that well-being can be conceptualized using the aforementioned Work, Life, and Work–Life domains. These dimensions were developed through focus groups with soldiers, additional research conducted on well-being (Bowles, 2014; Bowles, Cunningham & Jex, 2008; Jex, Cunningham, Bartone, Bates & Bowles, 2011), and literature reviews. These dimensions were developed earlier as part of the Work–Life Well-Being Inventory, designed specifically to assess service member well-being and have been conceptualized into different domains previously as well (Bowles, 2014; Bowles et al., 2008; Jex et al., 2011). The leader and organization supporting the family dimension was the only dimension theoretically derived for this model. The 19 dimensions that influence well-being are divided into three domains, which are listed in Fig. 14.2. These dimensions in the Work–Life Well-being Inventory look at the positive functioning of individuals. Joseph and Wood (2010) called for psychologists to use this type of positive approach to assessment as opposed to focusing on negative functioning.

In what follows, we describe the dimensions in each well-being domain and discuss the relevant supporting literature. Based on this literature , we provide recommendations for providers, educators, and leaders for ways to enhance the well-being of military members and families. We also suggest self-management approaches that can help service members preserve and increase their well-being. Self-management tools such as books, Internet, phone application for areas such as mindfulness, finances, stress management, and sleep, to mention a few, can promote behavioral changes and good life decisions. Readers may find more self-management tools at Military One Source, a free resource that offers health and wellness coaches to help service members accomplish goals and improve their well-being (Military One Source, 2017).

Work Domain: 7 Dimensions of Work Well-Being

Positive Work Environment and Positive Leader Support

Positive leader support in a positive work environment is an environment with a competent supportive leader that strives to enhance morale and culture at work (Bowles, 2014). The literature on well-being in professional environments highlights several factors relating well-being to positive work environment and positive leader support. There is moderate evidence that employee work well-being, as demonstrated through employee sick leave and disability pensions, is related to positive relationships with leadership (Kuoppala, Lamminpää, Liira, & Vainio, 2008). Research has found that leaders with active and supportive styles can positively impact employee well-being (Van Dierendonck, Haynes, Borrill, & Stride, 2004). Research has also found that employees reported lower burnout in work environments in which supervisors rated high on consideration (Seltzer & Numerof, 1988). This research suggests a relationship between positive interactions with an organizational leader and employee well-being.

Transformational leadership may be a key element for leaders to maximize well-being among employees. It has been defined as that which “emphasizes satisfying basic needs and meeting higher desires through inspiring followers to provide newer solutions and create a better workplace” (Ghasabeh, Soosay, & Reaiche, 2015, p. 462). A longitudinal study found a relationship between managers trained in transformational leadership and positive employee sleep quality (Munir & Nielson, 2009). This study indicates that transformational leadership may influence well-being by creating a productive relationship between employees and leaders and by supporting healthy habits such as sleep.

Research has shown that good leadership, along with the individual tendency to find benefits in adversity, may serve to buffer the potential ill effects of combat exposure, as evidenced by fewer PTSD symptoms (Wood, Foran, Britt, & Wright, 2012). In a study examining unit cohesion and PTSD in deployed UK service members, perceived interest of leaders in their service member thoughts or actions was associated with a reduced probability of PTSD (Du Preez, Sundin, Wessely, & Fear, 2012). The study suggests that positive leader support impacts the well-being of deployed service members in a military environment.

It is clear that supervisors and leaders influence the broader workplace dynamic and stressors that may threaten employee well-being. However, a more nuanced view of the research is appropriate to understand the positive leadership support dimension. For example, when examining military recruiters, a positive work environment is correlated with certain aspects of emotional intelligence: flexibility in adapting to new circumstances and environments, emotional awareness, happiness, empathy, and interpersonal relationships as well as agreeableness, adaptiveness, extroversion, and conscientiousness (Bowles, 2014). Thus, individual-level personality traits and emotional intelligence skills of soldiers also appear to have an impact on their experiences of the work environment.

Coworker Support

Another important factor in the cultivation of well-being among service members is coworker social support . Coworker support is feeling supported, respected, and valued as a team member by one’s coworkers (Bowles, 2014). Generally, workplace social support can protect individuals from the harmful effects of stressors, such as work overload or job strain. Research on a random sample of Swedish workers found that employees who were socially isolated at work showed higher incidences of morbidity and mortality, and had a higher risk for cardiovascular disease when compared with employees who worked alongside others (Johnson, Hall, & Theorell, 1989). A military study found that peer support was negatively correlated with turnover intention and positively related to job satisfaction in an Air Force military law enforcement agency (Sachau, Gertz, Matsch, Johnson Palmer, & Englert, 2012).

Cohesive unit culture describes units that are bonded and emotionally supportive of their members. In a sample of over 4000 male regular and reserve United Kingdom military members from all the services, researchers found that unit cohesion was correlated with a lower risk of PTSD and other common mental disorders for service members (Du Preez et al., 2012). As discussed, support of coworkers can lessen job strain and risks of associated illnesses, including heart disease, PTSD, and other mental disorders.

Trust in the Leader and Organization

Trusting a leader and organization means that a subordinate confidently relies on the leader to do what he says he will do, and experiences their organization’s culture as consistent with standards. In general, greater trust has been related to greater well-being (conceptualized as health, happiness, and life satisfaction) especially among older adult populations when examining individuals from 83 countries (Poulin & Haase, 2015). In their study of trust and leadership in the People’s Republic of China, Liu and colleagues described trust as it relates to leadership as a “positive perception or belief that followers are ‘willing/obligated to be vulnerable’ to their leaders” (Liu, Siu, & Shi, 2010). These researchers found that workers’ trust in their leaders and perceived self-efficacy partially mediated the relationship between transformational leadership and employee satisfaction. Trust in the leaders and perceived self-efficacy also mediated the influence of transformational leadership on employee-perceived job-stress and stress symptoms (Liu et al., 2010). Similarly, in a sample of Canadian forces , Tremblay (2010) found that employees’ perceptions of leader fairness and trust in leaders were related to unit commitment (suggestive of work well-being). These findings suggest that trust plays a central role in the impact transformational leadership has on employee well-being.

In looking at the role of trust in the supervisor–trainee accountant relationship , Chughtai, Byrne, and Flood (2015) found that trust mediated the impact of ethical leadership on work engagement and emotional exhaustion. Ethical leadership describes when leaders exhibit and promote appropriate conduct in the workplace through their individual actions and interpersonal relationships. Chughtai et al. (2015) found ethical leadership fostered employees’ feelings of trust toward their supervisors, which encouraged employees’ work engagement and decreased their emotional exhaustion. In another study of trust among Spanish employees, researchers indicated that interpersonal trust was positively associated with job satisfaction, and work stress partially mediated this relationship (Guinot, Chiva, & Roca Puig, 2013). Thus, trust may serve as an important component of employee health and well-being that fosters positive relationships between leaders and their subordinates as part of a positive work environment.

Negative Supervision

Negative supervision describes instances in which a supervisor, superior, or leader is critical of an employee’s work, engages in micromanagement, or sets unrealistic expectations of workers (Bowles, 2014). Mathieu (2012) examined literature on the role of managers’ traits associated with personality disorder (psychopathic, narcissistic, and obsessive–compulsive) and found that behaviors such as dishonesty, unpredictability, and abusiveness could be toxic to employee well-being. Employees working for a supervisor whom they perceive to be abusive have reported reduced well-being in the form of general life dissatisfaction, job dissatisfaction, psychological distress, family and work–life conflict, and reduced organizational commitment (Tepper, 2000). The first four conditions are more pronounced for employees with less mobility to leave their jobs.

Finally, Kelloway and Barling (2010) conducted a review of the existing studies on the impact that leadership has on general occupational health and well-being. Generally, they found that abusive supervision was related to outcomes that hinder employee well-being, specifically manifesting as burnout, decreased self-esteem, increased employee stress, and decreased self-efficacy (Kelloway & Barling 2010).

Job Stress

Job stress refers to work demands that exceed one’s resources and negatively impact the person and/or organization. Research has documented a significant relationship between job stress and adverse outcomes. Military job stress in particular has been observed to have a longitudinal impact on service members. Vinokur, Pierce, Lewandowski-Romps, Hofboll, and Galea (2011) found that exposure to combat trauma increased the likelihood of developing post-traumatic stress symptoms which, in turn, predicted reduction in adaptive resources, and perceived health and functioning. Just as an increase in job stress can have a detrimental impact on current and future well-being, reduction in job stress can also have a beneficial effect. In a study, low job stress among Army recruiters was found to be positively correlated with greater openness (Bowles, 2014).

In a review of psychological detachment (mentally separating oneself from work during nonwork time) by Sonnentag and Fritz (2015), those with a lack of psychological detachment were generally found to report greater stress symptoms, lower life satisfaction, and less work engagement. The authors did acknowledge that this “lack of detachment” may sometimes serve a positive purpose (such as when reflecting on positive work events or outcomes). In a study examining work well-being in a medical laboratory, researchers identified four distinct factors to be related to work well-being: job satisfaction, burnout, work engagement, and job stress (Narainsamy & Van Der Westhuizen, 2013). In this work setting, the strongest component of well-being is job satisfaction. These studies indicate that well-being in the area of job stress is important for the workforce.

How stress is addressed by leaders has the potential to foster either a more positive or negative work environment, and in turn can affect stress levels of workers (Bartone, 2017). Gurt, Schwennen, and Elke (2011) sought to determine whether health-specific leadership practices, which can be thought of as a leader’s explicit thoughts and actions to address the health of his or her employees, influenced employee well-being. They found that sound general leadership practices lowered job stress of employees of the German tax administration by reducing role ambiguity and producing a better climate for employees’ health and job satisfaction (Gurt et al., 2011). The study shows that a leader’s awareness of employees not only creates a more welcoming and positive work environment, but may also reduce job stress and enhance well-being.

Realistic Work Demands

Realistic work demands refers to the presence of clear, achievable, and reasonable work assignments (Bowles, 2014). The military has distinct and demanding work expectations to include service members taking on long hours and new leadership roles. Additionally, service members are expected to offer (unless they feel it is unethical or immoral) loyalty to a new leader, despite his or her ability, or inability, to lead. Within any given job assignment, being a valued member of the team is often based on how quickly you learn your new mission and contribute to the success of the operation. Over the course of a military career, technical abilities are expected initially on the job, with a subsequent expectation that a service member will be a generalist, capable of holding managerial positions at successively higher levels of responsibility.

Despite these high expectations, the presence of unreasonable work demands has affected job performance and led to the creation of policies to mitigate such demands. Research has shown that working long hours during a week results in reduced performance on psychophysiological tests and increased likelihood of physical injuries. This occurs increasingly with 12-h shifts combined with more than 40-h work weeks (U.S. Department of Health and Human Service [DHHS], 2004). Military members who work 12-h shifts, such as military police or security forces, are often required to show up 1-h early and remain up to an hour later to complete paperwork, meaning their 12-h shift actually lasts 14-h.

Factors have been identified that can mitigate the negative impact of long or irregular work shifts on worker well-being. In a sample of German middle-aged adults, Obschonka and Silbereisen (2015) found that job autonomy, or the ability to make decisions about work, buffered the impact working nonstandard hours had on job satisfaction positively. The implication is that autonomous and independent military work roles may help offset the potential impact of long hours on service member well-being.

Motivation and Job Satisfaction

Motivation and job satisfaction engender determination and sense of accomplishment at work (previously Motivation and Pride; Bowles, 2014). Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the role of military service on the life of service members. The “military-as-turning point” hypothesis conceptualizes military service as affording opportunities for growth and development, whereas the “life-course-disruption” hypothesis views service as undermining relationships and social connectivity (Segal & Lane, 2016). Motivation and job satisfaction may help to explain these dramatically divergent conceptualizations of military service, and demonstrate that both may be plausible. Chambel, Castanheira, Oliveira-Cruz, and Lopes (2015), in a study of Portuguese soldiers , found that autonomous work motivation was positively related to work engagement and negatively related to burnout, whereas extrinsic (controlled) motivation was negatively associated with the same patterns (Chambel et al., 2015). Moreover, autonomous work motivation was identified as a mediator between both contextual (perceived organizational support and leader support) factors and workplace well-being (Chambel et al., 2015). Thus, individuals who are autonomously motivated to work are more likely to experience enhanced well-being and greater satisfaction in their work. Researchers also found that hardiness, which consists of control, challenge, and commitment in life, was associated with job satisfaction (Eschleman, Bowling, & Alarcon, 2010).

Life Domain: 5 Dimensions of Life Well-Being

Friendship Support

Friendship support involves being listened to, understood, supported emotionally, and supported in problem-solving by a friend network (Bowles, 2014). A study on same-gender friendships among college students differentiated between the types of support a friend gives and overall well-being. Morelli, Lee, Arnn, and Zaki (2015) conducted a study in which participants kept a daily diary documenting support received from close friends. Researchers discovered emotional support (e.g., empathy) was strongly associated with well-being in the individual providing the support. Findings also showed that one friend’s instrumental support (e.g., tangible assistance) of another friend served to enhance the well-being of both giver and receiver. Other researchers have found that an increased number of friendships and relationships buffer stress (Cohen & Willis, 1985).

Satisfaction with Medical Services

Satisfaction with medical services relates to medical and dental care that is adequate, accessible, and affordable for the entire family (Bowles, 2014). Apart from relationships and social support, access to adequate health services also impacts well-being, albeit in interesting ways. Having ready access to health care within the military system (which is also free to military members and their families) may contribute to service member well-being. For example, a RAND study of health care for veterans found that easy access to quality health care was related to improved quality-of-life enjoyment and satisfaction (Eberhart et al., 2016). A study of active duty Army recruiters also found that satisfaction with medical services was positively related to emotional well-being (Bowles, 2014). However, access to specialty care in medicine and dentistry is sometimes limited or delayed, which could have a negative impact on well-being. Additionally, when service members or veterans are based in communities that are distant from military treatment facilities, they are restricted to using health care providers who accept Tricare insurance. This limitation could result in greater difficulties obtaining needed health care, and in turn negatively affect satisfaction and well-being. A comprehensive NATO study of military recruitment and retention found that medical benefits are often an important source of satisfaction and well-being for service members, and influence retention (NATO, 2007). Thus, medical services are significant benefits for military members and their families, and can impact well-being in a number of ways.

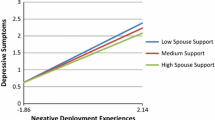

Marital Strength and Family Support

Marital strength and family support involve the service member feeling supported by his/her significant other, immediate family, and extended family (Bowles, 2014). Marital strength and family support have been associated with more positive interpersonal relationships (Bowles, 2014). Marital strength and family support are also related to lower levels of service member neuroticism or resilience, and greater emotional intelligence in the areas of problem-solving, happiness, flexibility, self-regard, emotional awareness, and interpersonal skills (Bowles, 2014). Skomorovsky, Hujaleh, and Wolejszo (2015) found that military demands on family life for Canadian armed forces personnel may impact marital satisfaction in that intimate partner violence was related to decreased psychological well-being (depressive symptoms). Pietrzak et al. (2010) found that the social support a service member receives from family (as well as friends, coworkers, employers, and community) served as a mediator in the relation between PTSD and psychosocial functioning . This suggests that family and other support may also affect the emotional well-being of Reserve and National Guard service members who generally spend more time with civilian coworkers and employers than with military coworkers. For severely injured wounded warriors, family support was related to emotional well-being and also predicted fewer sleep problems (Bowles, Bartone, Seidler, & Legner, 2014).

Financial Stability

Bowles (2014) identified financial stability as the presence of a savings plan and individual satisfaction with one’s financial situation. Gallup conducted a study on 1000 US citizens and determined that there is no improvement in well-being beyond earning $75,000 annually. While more money was not suggestive of emotional happiness, less money appeared to be associated with more emotional pain (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). Lower income, contrastingly, was correlated with threats to well-being, including divorce, being alone, and health problems such as asthma (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). Lower earnings of more junior service members may cause additional stress on the family, particularly if living in a high cost area.

Other researchers recognized the financial difficulties service members and veterans encounter post deployment. A study conducted on Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans found that a lack of financial well-being was associated with psychological disorders (post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, and traumatic brain injury) (Elbogen, Johnson, Wagner, Newton, & Beckham, 2012). While most military families achieve financial stability, spouses’ earnings may be reduced, and some junior enlisted service members and their family may even receive food stamps to support themselves (Hosek & Wadsworth, 2013). In another study of the military population, researchers found that financial debt was related to lower psychological well-being, while soldiers with larger emergency saving accounts (a marker of better financial well-being) had greater psychological well-being (Bell et al., 2014). Similarly, in the civilian population, Pereira and Coelho (2013) looked at the European Social Survey data of 24 countries and found that perceived income adequacy was positively related to subjective well-being. Specifically, they found subjective well-being was associated with perceived access to credit, and that access to credit, in turn, mediates the influence of income on well-being (Pereira & Coelho, 2013). These findings lend further confirmation to the importance of financial stability for healthy well-being. Most large US military installations provide financial services with financial specialists who can advise service members on financial matters at no cost to the service member (Bowles et al., 2012).

Satisfaction in Community

Family Satisfaction in Community (was previously Community Supports Family) is support to family and service member from the community, to include parent and children satisfaction of the school system, spouse’s employability, and family recreation resources (Bowles, 2014). The regular moves to new locations, service member deployments, and exposure to trauma could influence academic and well-being outcomes for children (Palmer, 2008). Another determinant of well-being is the spouse’s ability to find employment. Avoiding boredom and personal fulfillment are some of the reasons spouses want to be employed (Castaneda & Harrell, 2008). Careers for spouses are regularly interrupted due to frequent and disruptive moves to new locations, service members’ deployment or training exercises, and child care challenges (Castaneda & Harrell, 2008; Hosek & MacDermid Wadsworth, 2013). For these reasons, employers may develop employment stigmatization, and, consequently, hesitate to hire military spouses (Castaneda & Harrell, 2008; Hosek & MacDermid Wadsworth, 2013). Further, Hosek and MacDermid Wadsworth (2013) state that military spouses, when compared to similar civilian spouses, work fewer hours or are unemployed. In addition, military spouses often earn less than their civilian counterparts (Hosek & MacDermid Wadsworth, 2013). Wang, Nyutu, Tran, and Spears (2015) attempted to identify protective factors that promote well-being in military spouses. They discovered that the social support military spouses received from their friends was associated with a sense of community and increased well-being (Wang et al., 2015).

Work-Life Domain: 7 Dimensions of Work–Life Well-Being

Emotional Well-Being

Emotional well-being has been defined as feeling good about oneself and maintaining a spirit of optimism and positivity toward life and its challenges (Bowles, 2014). Past research on North American adults has found that the emotional intelligence areas of happiness, self-actualization, and self-regard are related to subjective well-being (Bar-on, 2012). In a study in the Chinese population , students with high levels of resilience had more positive cognitions and higher emotional well-being (high life satisfaction and low depression levels) (Mak, Ng, & Wong, 2011). Additionally, hardiness has been found to be associated with the well-being areas to include job satisfaction, life satisfaction, positive state affect, personal growth, engagement, happiness, and quality of life (Eschleman et al., 2010). Emotional well-being is important for service members in sustaining and maintaining positive emotional states for performance levels both during and after combat operations.

The Battlemind program has instituted interventions with service members and found positive emotional well-being effects (reduced PTSD symptoms and depression symptoms) when compared against a control or comparison group (Adler, Bliese, McGurk, Hoge, & Castro, 2009; Castro, Adler, McGurk, & Bliese, 2012). Other simple interventions may also have an impact on greater well-being for service members. In a study examining mindfulness-based practice with 174 adults, participants reported greater mindfulness, stress symptom reduction, and improved well-being (Carmody & Baer, 2008). Researchers examining gratitude found that appreciative behaviors led to higher perceived social support, as well as lower levels of depression and stress (Wood, Maltby, Gillett, Linley, & Joseph, 2008). A survey on forgiveness, using a sample of over 1500 persons over the age of 66, found that being able to forgive others was associated with fewer depressive symptoms (Krause & Ellison, 2003). In another research related to emotional well-being, young adults reported greater emotional well-being (positive affect and flourishing) on days of greater creative activity (Conner, DeYoung & Silvia 2016). Volunteerism was yet another activity that was reported to improve personal well-being (happiness, life satisfaction, self- esteem, sense of control over life, physical health, and reduced depression) (Thoits & Hewitt, 2001).

Duvall and Kaplan (2014) studied the effects of outdoor recreation on the emotional well-being (positive and negative affect), social functioning, and overall outlook of veterans. After a week of outdoor recreation, veterans were found to have improvements in all of these areas (decrease in negative affect and increases in all others), which continued for 3–4 weeks. Finally, an online automated mental fitness self-help intervention for adults significantly improved well-being by reducing mild-to-moderate depression and anxiety symptoms when compared to a waiting list control group (Bolier et al., 2013).

Satisfaction with Work, Family, and Leisure Time

This is an effort to achieve work–life satisfaction with work, family, and leisure time well-being (Bowles, 2014). There can often be a tension between the needs of the family and work that plays a major role in military couples’ work–life conflict. Researchers found work–family conflict for service members was moderately related to workload (hours of sleep and training in the past 6 months) (Britt & Dawson, 2005), which can be mediated by the leader and service member. In a qualitative study, some deployed mothers reported difficulty with perceived command nonsupport relating to family care plans in managing issues with at-home caretakers (Goodman et al., 2013). Work-to-family conflict (disruptions that occur in the family because of workplace responsibilities) and family-to-work conflict (disruptions that occur in the workplace because of family responsibilities) were related to low job satisfaction and job turnover intention for service members in a military security organization (Sachau et al., 2012).

A study of leisure time among combat veterans with PTSD found that a recreational trip (3-night fly fishing trip) was effective in reducing negative mood, depression, anxiety, and somatic stress. The veterans’ sleep quality also improved, and PTSD symptoms lessened in severity at the 6-week follow-up (Vella, Milligan, & Bennett, 2013). This speaks to the importance of leisure time in improving overall well-being and overall work–life satisfaction for service members and their families.

Personal Development

The well-being dimension of personal development is the level of satisfaction with continued education, opportunities for personal growth, and purposeful activities in life (Bowles, 2014). Personal growth and life purpose have long been recognized as important for well-being (Ryff, 1989). Research with United States Army recruiters found that those who were satisfied with their personal development also reported being more open and adaptive (Bowles, 2014). A recent study finds that among Mexican adults, subjective (emotional) well-being, personal growth, and purpose in life are all related to perceived quality of life (González-Celis, Chávez-Becerra, Maldonado-Saucedo, Vidaña-Gaytán, & Magallanes-Rodríguez, 2016). Similarly, researchers in Norway examined two separate dimensions of well-being: life satisfaction and personal growth. In a sample of health care workers, life satisfaction was associated with reduced sick leave. On the other hand, personal growth showed a small but positive correlation with sick leave (Straume & Vitteroso, 2012). The authors suggest that workers who are higher in personal growth, which includes curiosity, competence, and complexity, may simply be more willing to admit when they are sick and stay home from work, especially if the work is perceived as boring or uninteresting. This implies work that is meaningful and provides personal growth and development opportunities will lead to greater engagement and well-being in the workforce.

Healthy Habits

Healthy habits of service members include the amount of satisfaction with diet, exercise, and sleep behavior. Various barriers may preclude healthy habits in areas such as diet, exercise, and sleep. In one relevant study, researchers conducted a 10-week wellness intervention based on the disconnected values model (DVM; when there is a disconnect between one’s values and one’s behavior regarding exercise; Brinthaupt, Kang, & Anshel, 2010). Following the intervention, which included exercise coaching and discussion of discordant values, participants showed increased exercise and health, as well as more happiness and health satisfaction.

Diet is another health area that can influence health and well-being. Individuals who eat a well-balanced diet report feeling healthier overall. Blanchflower, Oswald, and Stewart-Brown (2012) found that fruit and vegetable consumption was positively linked with well-being (happiness and mental health) based on health surveys from 2007 to 2010 in the United Kingdom. In another survey study of food consumption conducted in 2007 and 2009 of the Australian population, researchers found that greater fruit and vegetable intake was associated with increased well-being (happiness and life satisfaction) (Mujcic & Oswald, 2016). Food choices that service members make may therefore affect their overall well-being as well. Service members completing a well-being program (healthy eating and exercise) and successfully losing weight reported perceived improvements in physical well-being, material well-being (income and living situation), and vacationing behavior (Bowles, Picano, Epperly, & Myers, 2006).

Other studies have identified exercise as a factor that impacts well-being. Researchers at a Turkish university examined the effect of a 13-week tennis exercise program. The students in this program played tennis for 90 min once a week. Participants had a significant decrease in their Symptoms Checklist-90 anxiety and depression scores, and Beck Anxiety Inventory and Beck Depression Inventory post-test scores (Yazici, Gul, Yazici, & Gul, 2016). Another study posited that the relationship between exercise and well-being is more complicated. For example, motivation has been shown to moderate the relationship between exercise habits and well-being. Research has shown that undergraduate students who exercised for 6 months or more and were intrinsically motivated generally benefited from better psychological well-being, while those who exercised for less than 6 months and were extrinsically motivated suffered from a lack of psychological well-being (Maltby & Day, 2001). The study is applicable to service members because the exercise, strength, and conditioning required within military life may impact the well-being of service members differently, depending on whether they are intrinsically or extrinsically motivated.

Sleep among service members can have a direct impact on individual and collective work productivity. Research has demonstrated shorter sleep cycle duration and poor sleep quality are correlated with lower unit readiness in combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan (Troxel et al., 2015). Sleep cycles of service members can be influenced by various challenges, one of which is staffing. Understaffing may affect both acute and chronic fatigue levels by increasing the probability of extended duty hours, shortened sleep opportunities, inconsistent work–rest cycles, and circadian disruption. Unfortunately, most schedulers and/or leaders do not receive formal training in shiftwork scheduling or lack a true understanding of the physiological effects induced by schedules and changes in work schedules. Poorly designed shift schedules cause excessive disruption to shift workers’ circadian rhythms. In many cases, service members are asked to make significant changes to their lifestyle to obtain adequate sleep (see also Campbell et al., Chap. 15, this volume).

Spirituality

Spirituality has to do with the satisfaction level of spiritual and/or religious practices and resources available (Bowles, 2014). Studies of spirituality and emotional well-being of individuals with cancer have found mixed results (Visser, Garssen, & Vingerhoets, 2010). Research examining college students’ spiritual well-being found that students scoring high on spiritual health had better psychosocial outcome scores when examining hopelessness, loneliness, and self-esteem (Hammermeister & Peterson, 2001). In another study with college students, researchers found personal spirituality served as a moderator of the relationship between stressors and life satisfaction (Fabricatore, Handal, & Fenzel, 2000).

In a study conducted with a veteran population with war-related PTSD, researchers (Bormann, Liu, Thorp, & Lang, 2012) tested a mantram (i.e. repeating a sacred word or phrase) intervention with other support skills in which veterans attended six weekly classes for 90 min a week. Findings showed that veterans who received the mantram intervention experienced a reduction in PTSD symptoms and that emotional well-being was a mediator in this pathway. In other words, the intervention was associated with an increase in well-being, which in turn was correlated to a decrease in PTSD. Treatment approaches that make use of spiritualized meditation techniques show promise for increasing well-being and reducing stress-related symptoms in military personnel.

Leader and Organization Supporting the Family

Leader and Organization Supporting the family is the service members’ perception of and satisfaction with the individual and family support offered by leaders and the organization. Demands on the families of service members make the military a workplace with a unique set of stressors and challenges. Supervisors’ support of families can be important to the well-being of subordinates and employees. According to a civilian study, subordinates who reported less work–family conflict, more job satisfaction, and greater compliance with the work safety program considered their supervisors to be family-supportive (Kossek & Hammer, 2008).

Unit support is another organizational component that can serve to support military families and thus contribute to service members’ well-being. Researchers found that organizational support had a stronger relationship than supervisor and peer support with low work-to-family conflict, turnover intention, and job satisfaction in an Air Force security agency (Sachau et al., 2012).

Community Family Support

Satisfaction in the community, previously Satisfaction with Community, describes the military family’s overall satisfaction with housing, neighborhood, and support from their community (Bowles, 2014). Researchers conducting a survey with military personnel in all services found that the majority of military personnel reported being satisfied with their quality of neighborhood (77%), residence (71%), and affordability (55%) (Bissell, Crosslin, & Hathaway, 2010). In a study on US Air Force personnel, researchers’ findings suggest social networks and unit support were related to families’ abilities to adapt to their community (Bowen, Mancini, Martin, Ware, & Nelson, 2003). Researchers have noted that family support, specifically for spouses, through community members (nonmilitary friends), as well as family and military spouses, positively affected psychological well-being with deployed partners in the Canadian armed forces (Skomorovsky, 2014). Each distinct source of social support received by the family provides unique contributions to well-being, including community support.

In a military study , Han et al. (2014) assessed service members’ perceived social support (community, family, and coworker) at post-deployment and found that active duty service members with lower levels of PTSD symptoms had higher social support systems. This suggests that social support may serve as a buffer against PTSD and other disorders (Han et al., 2014). Such a finding shows that the community component of social support can play an integral factor in well-being for active duty service members and underscores the importance of the community in mitigating stress.

To summarize, these sections have offered dimensions that are components for service member well-being, conceptualized under Work, Life, and Work–Life domains. The dimensions have been supported by research in both the military and civilian populations. When these well-being dimensions are present, positive adaptive outcomes can be the result for the service member.

Adaptive Outcomes for Service Members

Based on the research reviewed, there are a number of outcomes that can be the result of service members having positive well-being dimensions. In the Work domain, well-being dimensions are adaptive in several ways. Adaptive work well-being outcomes include job satisfaction, optimal performance, work safety, unit commitment, and positive work climate. For the Work–Life domain , the adaptive outcomes that occur for an individual are positive affect, appropriate sleep, lower stress and resilience, and physical and psychological health. Interpersonally, at work and home, there is greater social connectedness and low work–life conflict. For the Life domain, marital and family satisfaction, financial stability, and detachment from work are important outcomes to well-being.

In the following sections, the application of these dimensions of service member well-being based on the previously reviewed literature is provided. Adaptive outcomes for well-being were identified for service members when well-being is occurring in many of the dimensions. The previous research described to support the well-being dimensions for service members is now translated for providers working with five resources to promote service member well-being. These five resources are providers, service members, families, educators, and/or trainers and leaders.

Five Resources for Enhancing Service Member Well-Being

Providers

Well-being ultimately comes from within. However, there are resources that can facilitate, develop, and evolve personal happiness, meaning, and satisfaction in life. Various providers (e.g., psychologists, primary care physicians, psychiatrists, chaplains, social workers, psychiatric nurses, marriage and family counselors, and military family life counselor) are often in a position to serve as a coach and or consultant, able to influence the individual to achieve greater well-being. Providers can also serve as an organizing force and direct service members to other resource influencers such as leadership, the family, unit trainers, and community educators. The domains and their dimensions offer a helpful framework for resources to assess and influence well-being.

Providers can offer clinical and community strength-based well-being psychology (focusing on a person’s positive well-being outcomes) through direct contact or other supporting means (i.e., people, organizations, websites, bibliotherapy) for service and family members, unit trainers, community educators, and leaders that support well-being in the military. It is important to note that the practical strategies listed below can be applied to individuals (e.g., in provider–patient interactions or coaching) and groups (e.g., if a leader requests a particular subject-matter expert to provide preventive education to an entire team). This section explores the three domains of well-being and how providers can serve as a resource and influencer to support healthy well-being (see Table 14.1).

In the Work domain of well-being providers can help develop hardiness and resilience-building skills, which have been associated with job satisfaction well-being. Providers may also encourage service members to develop their social friend networks to increase overall well-being through social support provided by coworkers. In addition, they can also teach and coach interpersonal mindfulness and stress management techniques to the service member for better managing relationships. Providers may also play a role in assisting service members in developing intrinsic motivation, and may help to identify alternative career paths as they strive toward their personal and military goals.

In the Life domain , providers may encourage the formation of support networks of friends outside the military in order to sustain general well-being. Providers may influence community well-being of service members and their families by teaching them how to integrate and utilize their community resources, such as financial specialists that are provided within the military for life financial planning.

In the combined Work–Life domain , providers can support emotional well-being of service members by encouraging purposeful life and personal growth activities. Providers can foster well-being by advocating for healthy habits, including adequate sleep, healthy eating, exercise, and spiritual or attitudinal health. Providers can also have an impact in the Work–Life domain by conveying skills to service members and their families about how to satisfy work, family, and leisure time needs. For psychological strength building, providers can look at skill development in areas such as creativity, forgiveness, gratitude, and hardiness in service members. Service members may also develop their emotional intelligence in the areas of self-regard, happiness, and self-actualization for subjective well-being by working with the provider. Well-being can further be developed through technological approaches, such as web-based mental fitness self-help interventions or technology applications (see also Campise et al., Chap. 26, this volume). Providers can be coaches and consultants in developing service members, leaders, unit trainers, families, and/or community educators to influence service members toward greater well-being. Focusing on well-being destigmatizes behavioral health conditions, and fosters positive growth approaches in well-being in clinics, units, and educational training centers.

Service Members

The provider can encourage the service member to be self-sufficient in well-being whenever they interact (see Table 14.2). Service members can gain self-management skills through all the resources mentioned. Service members can enhance their well-being outside a therapeutic setting. In the work well-being area, reading material on self-management tools may help service members further enhance well-being. Hardiness and resilience are valuable attributes within the military population, and any opportunity to build these will pay dividends in both mission effectiveness and in personal well-being. Building interpersonal skills through professional organizations would be another wise time investment, as it may facilitate coworker relationships that are related to job satisfaction.

In the Life domain, friendship is a consistent positive influencer of well-being, specifically when those friends listen and provide support when solving problems. Service members need to become educated on financial resources available through the military and self-sufficient with developing financial wealth, emergency savings, and crisis situations. In addition, service members need to cultivate marital strength and family support, which are related to more positive interpersonal relationships and greater happiness. Having family support is also related to emotional well-being. Service members can engage in the community to garner more social support for their spouses, which would benefit the family during deployments.

The service member can self-educate and practice ways to manage the work–life well-being through stress-reduction techniques, outdoor recreation and vacations, and other healthy behaviors. Service members can be educated in practices of mindfulness, gratitude, and forgiveness, which may reduce stress and promote attributes like emotional intelligence and hardiness. Additionally, creative activity may foster well-being, positive affect, and a sense of flourishing. Recreational sports and vacation activities are also positive ways to further develop well-being. In addition, the service member can be supported in healthy eating by consuming fruits and vegetables, which has been related to happiness. For those inclined to the spiritual life, they can also be educated on the benefits of spirituality on well-being and referred to a Chaplain for additional support or to improve self-practice.

Families

Family members have access to providers as well as a number of helpful resources that can support well-being (see Table 14.3). Family members can also serve as a well-being resource in several areas to the service member. However, providers should be aware of red flags that can cause families distress (such as relational problems and child discipline challenges). These restrict the family from being a resource and instead create stress. For the Work Well-being domain, spouses and family members should be supportive of service members when separated during training exercises and deployments. Spouses and family members can utilize resilience and family support skills, obtained from various military service support groups or centers during the entire deployment cycle, to sustain the family. Some of the entities that support service members’ work, effort, and family readiness during these times are Family Readiness Groups, Army Community Service Center, Fleet and Family Support Center, Airmen and Family Readiness Center, Marine Corps Community Services, or Work Life Office. Family support and other types of support during the deployment cycle should be leveraged by providers working with the service member and/or family.

In the Life Well-being domain, social support (e.g., emotional support and instrumental assistance) provided by the family, coworkers, and community systems may meditate traumatic stress and psychosocial adjustment for service members. As previously reported, the strength of marriage and family is related to more positive interpersonal relationships, more adaptability, and greater happiness and emotional well-being for service members. Thus, family support can play an integral role for the returning service member’s well-being, particularly if they have a psychological or physical injury. Service members should also support their spouses in developing their nonmilitary support networks, as this has been found to contribute to the deployed member’s psychological well-being.

Financial stability , a component of the Life Well-being domain, may be impacted by the demands of the service member’s career. While a service member’s income is stable, a spouse’s income may be reduced or eliminated with each move. Enlisted couples with children may be particularly at risk for reduced financial well-being. As discussed earlier, some junior enlisted members and their families have needed to access food stamps. Financial debt has been related to lower psychological well-being, while larger emergency saving accounts have been linked to greater psychological well-being for service members. To support financial stability, families can meet with financial specialists, provided by the military, and come to a consensus on family budget and spending. Providers should also assess the family financial well-being and recommend the appropriate support services.

In the work–family well-being , the family should encourage a satisfactory work family environment by encouraging time for leisure activities and practicing healthy habits. Employing these behaviors during family time should promote work–life well-being and limit struggles with work and family time, thereby reducing stress for the service member in both environments. The provider and others should encourage work–life satisfaction strategies with the family if needed.

Unit Trainers/Community Educators

Unit trainers provide and coordinate training for a unit/squadron, while community educators provide family and financial resources. It is important for the providers to recognize the role the unit trainer and community educator resources can play in the service members’ life (see Table 14.4). Providers serve as consultants and perhaps guest speakers to units or community education events. It is important for providers to develop relationships with unit trainers to serve in multiple roles of providing support through unit mental health, enhance unit performance, and serve as presenter to unit training events or a community resilience seminar. Both unit trainers and community educators may serve as referral sources of clients to providers and help providers track relevant trends within the military community. Unit trainers and service members have mutual access to each other, and service members can seek out community education as well.

There are multiple different unit training and community educator roles and services that can support well-being. The unit trainer can provide training in a variety of areas, including professional training, sexual harassment, suicide education, safety on the job, and well-being and hardiness training, among other areas. The community educator in the military or civilian community may provide training and information on family resources, financial planning, transition/retirement planning, and other community education topics. In the area of work well-being, unit trainers can teach the importance of unit cohesion and coworker social support. They can also provide specific training such as unit cohesion education (e.g., trust within unit, superordinate unit goals) or team-building exercises, and monitor unit well-being for mission readiness. Military and civilian community education may offer workshops and seminars to teach service members how to develop their professional networks and coworker relationships to enhance their social support systems. Trainers can teach effective and positive transformational leadership skills in an attempt to promote positive leadership and improve well-being. They can also teach stress management and resilience-building skills which are also linked to improved well-being.

In the Life domain, community educators may provide workshops and/or seminars with a focus on developing a network of friends and support systems in and outside the military, through in-person meetings or social media interactions to sustain general well-being. Community educators may teach about financial stability, family resilience, and well-being, continuing to assist with the network building as service members and their family leave the military.

In the Work–Life domain , unit trainers and community educators can promote volunteerism and other civic contributions that have improved well-being. Community centers and educators can serve as resources to the service member for fitness programs, behavioral health and military life counselors, and medical support activities and religious events, as well as recommend spiritual support. They can also provide workshops on healthy life behavior, relationship development, and medical health awareness to reduce stress, develop well-being and resilience, and promote life satisfaction. Educators can also have an impact on the Work–Life domain by conveying skills to service members and their families about how to satisfy work and family conflicts and refer to Morale, Welfare, and Recreation for leisure opportunities to maximize well-being.

Leaders

Providers can serve as coaches and consultants to leaders to help them develop well-being within their organizations (see Table 14.5). Leaders have a direct and continuous influence on the well-being of service members under their direction. Leaders from civilian and military sectors may employ these approaches when considering how to best foster well-being.

The domain of Work Well-being is likely to be especially relevant for leaders. Based on examining the various dimensions in this domain, the following influencers in no particular order were found to have a positive impact on work well-being dimensions and can be modeled by leaders. Leaders that have demonstrated consideration of, or looking out for the welfare of, the employee have translated to lower burnout for employees. Active and supportive leaders have had a positive impact on the well-being of their personnel. Transformational leadership promotes such things as positive work environment and productive relationships that promote well-being. Leaders that provide social support (good information flow, employee improvement, and mitigate unnecessary job risks) can buffer subordinates’ traumatic stress. Leaders that practice ethical and trustworthy behavior can create trust, reduce emotional fatigue, and promote work engagement among employees. Leaders that create an environment of peer supportive networks create a climate where employees are satisfied and more inclined to stay with the organization. Leadership practices that are participatory and objective-focused that provide feedback help the psychological health climate in the work environment. This climate is also associated with lower role ambiguity and higher job satisfaction. Leaders and organizations that can create job autonomy and intrinsically motivate employees may mitigate the impact of working nonstandard hours and may reduce burnout, increase engagement, and enhance overall satisfaction. Leaders should constantly be aware of the level of responsibility they have with their personnel and the stewardship of promoting positive leadership. Negative leadership may create stress, burnout, family and work–life conflict, life and work dissatisfaction, and increased stress, impacting work negatively with less organizational commitment. Leaders must stay mindful of increasing employees’ hours beyond normal limits that may result in degraded performance and injuries as well as assessing employees that are working in isolated environments and operations that may reduce well-being.

In considering life well-being, leaders need to assure that service members and their families have adequate access to health care resources. To support members with PTS/PTSD, leaders may encourage support networks within and outside the military community as their subordinates return from deployment. Leaders need to continue to promote financial well-being for service members. Those that have large emergency saving funds have greater psychological well-being than those in financial debt. Finally, with new families joining the organization, leaders need to assure that there are adequate support systems and identified social networks in place for new members, as this is related to their adaptation into the community.

Finally, there are several work–life well-being dimensions that leaders may positively influence. Leaders may increase retention by being mindful of the bidirectional relationship of work–life conflict that can create tension for the service member and may decrease job dissatisfaction. Leaders encouraging healthy work safety practices are viewed as more family-supportive. Encouraging healthy habits such as healthy eating, sleep, recreation, and vacation are related to well-being, and improve both work and home environments. Proper sleep has been related to performance and unit readiness.

Conclusions

The military is a highly demanding occupation that presents service members with unique challenges requiring intense participation, focus, and stamina. Given the well-documented research on the harmful impact of operational stressors, including family separation and deployment, identifying resources that can mitigate adverse outcomes in service members is a vitally important undertaking. This chapter focused on critical well-being dimensions and five resources that can serve as protective factors for service members who face stressors in this inherently challenging career. Recommendations for preserving and enhancing well-being are framed in terms of three overarching domains: Work, Life, and Work–Life. These domains are further divided into 19 critical well-being dimensions that can influence a range of adaptive outcomes for military service members.

Given the stressful nature of military service, it is essential that service members experience a satisfactory number of these dimensions and positive resources in their lives. However, it is important to consider that well-being is a systemic process influenced by numerous environmental conditions. Outside forces will almost always have an impact on well-being. Well-being is often specific to unique aspects of the individual in addition to the operational context. Based on the service members’ individual recourses and the other four resources, they will respond better to certain initiatives or intrinsically be engaged in some well-being dimensions more than others. Service member well-being can be viewed as a balance between competing factors with the primary objective being to stabilize, strengthen, and sustain as many critical well-being dimensions as possible.

The key dimensions of well-being discussed in this chapter are based on a focus group and a review of the current research on well-being. There are certain limitations to the extant literature. Given the breadth of conceptualizations of well-being, there is a lack of systematic reviews and randomized control studies. Even among the completed studies, unique samples and methodological challenges limit the generalizability of the research. Additionally, it is likely that there are other dimensions of well-being not identified in our literature reviews and military focus groups. It is anticipated that our military well-being model will evolve based on more rigorous and comprehensive research. For example, the Millennium Cohort Family Study may help explain how military service impacts service members and their families long-term, and may offer insights into well-being.

Based on the authors’ professional observations and experience, each domain has one to three factors that are most important, and may be impacted through practical approaches. In the Work domain, positive leader support, personal motivation, and coworker support carry the most weight in overall well-being. Ideally, all dimensions are present and actively working in concert, including positive relationships with both superiors and coworkers, as well as a positive motivation and attitude resulting in an overall healthy work environment. Even when these relationships are not in perfect harmony, strength in one dimension might compensate for relative weakness in another. There are countless examples of coworkers bonding together and encouraging each other through negative leadership experiences. Similarly, a meaningful relationship with an inspirational supervisor and personal motivation can outweigh absent or contentious relationships with coworkers, such that employees are able to maintain their well-being at work despite not having many friends in the office. As noted above, training on transformational leadership may be the best practical strategy, and in this case, may help to align organization and service member motivation into superordinate goals and develop a climate of unit cohesion. This can enhance both individual well-being and relationships between employees, which can further improve individual well-being.

The Life domain may differ for married versus single service members. For married and single service members, marital strength and/or family support and friendship are the most important dimensions. Many single members still consider their mother, father, siblings, and friends as important well-being dimensions, and the most important will vary by service members. For married service members , while family would be expected to be more important, friendship also plays an important role in the Life domain. Most leaders and other professionals would likely agree that marital satisfaction is highly correlated with individual well-being and overall mission effectiveness, a term that reflects an individual’s ability to perform his or her intended duties within the organization. Many marriage-focused and family-focused programs are already available in most organizations. This includes counseling through Military and Family Life Consultants and traditional Behavioral Health resources, as well as Strong Bonds and other Chaplain-led initiatives. To foster well-being in this domain, leaders can increase awareness of these resources and ensure adequate opportunity (i.e., breaks from the mission) for service members to access them. As noted, marital strength is not relevant for single service members, though meaningful relationships with their family of origin and significant other (as applicable) may impact their individual well-being. As with the married service members, the resources for the single service member already exist and must simply be leveraged more efficiently. Social connectedness can be improved through any number of programs such as “Better Opportunities for Single Soldiers,” which facilitate fun off-post activities to help build new friendships. Further, much of the research on the other Life dimensions (i.e., satisfaction with medical services and satisfaction in community) demonstrated particular relevance for spouses or other immediately affected family members, and have a secondary impact on the service member. The remaining dimension, financial stability, may be equally meaningful, and leaders or other concerned friends and coworkers would be wise to recognize and educate service members who struggle in this area. Financial support is available through various Garrison resources, such as Army Community Services, which can educate service members to increase financial stability, or offer various loan options for those who find themselves in debt.

Behavior change and habit sustainment of healthy habits may be the most important dimensions in the Work–Life domain . Sleep, diet, and exercise have been dubbed the “Performance Triad” in some circles. Sleep has an impact on all aspects of our lives. Service members’ sleep habits impacted by temporary circumstances (such as a deployment or shift change) can morph into long-standing unhealthy sleep patterns or clinical insomnia. Two other important areas of the work–life well-being domain are emotional well-being (e.g., how one feels or one’s attitude toward life), and work and life satisfaction. The practical approach to these dimensions will nearly always include a combination of educational messaging and opportunities to guide behavior change.

The well-being dimensions can be positive or negative influencers. Our review and experience revealed that some of the most important dimensions that positively influence well-being are the family, marital relationship, and friendship. The second most important area was the positive leader and work environment, and last was the healthy habits of the service member. These same dimensions, when present in a qualitatively negative manner or when altogether absent, can also have the strongest negative influence on well-being. In terms of negative influencers, unsupportive, demanding, or even abusive leaders, along with poor relationships or social support within the marriage, family, and/or friendships, lead to work–family dissatisfaction. The other significant negative influencer is poor service member’s physical and emotional health habits.

When thinking in terms of the five resources that impact well-being, although the service member is ultimately responsible for his or her behaviors, other external resources can be very important influencers. The next greatest influencer of the service member’s well-being is the family, particularly in the Life and Work–Life domains . The leader may be equally as important as the family in this hierarchy of influence, playing a fundamental role in creating a military work environment that emphasizes the importance of the Work domain of well-being. The influence of the provider, unit trainer, and community educators may be limited due to irregular contact or because they lack the authority inherent in chain of command. Knowing this, the provider must make the most of any given encounter with service members to help each person develop effective tools to enhance well-being. They must find ways to leverage evidence-based strategies to effectively impact leadership’s understanding and support of well-being. Additionally, providers must support the family through identified resources and communicate effective messages regarding well-being with the community educators and unit trainers.

Further research on service members, leaders, and work–family well-being adaptive outcomes is warranted. Based on our examination of the literature, several dimensions of well-being were identified and documented that can be reinforced by the provider, family, educator-trainer, and leader for the benefit of the service member. These four resources should support service member development and practice well-being through the three significant influencers we identified (family, leadership, and service member healthy behavior). Researchers can also focus on better understanding the role of these four resources in supporting the development of service member self-management techniques for healthy habits, relationship skills (with spouse, children, significant other, or friends), and leadership/followership skills.

Work, Life, and Work–Life domains of well-being are interconnected domains and therefore should be conceptualized as influencing and overlapping with one another. A service member’s well-being relies on how well he or she can manage or satisfy the two demanding and highly involved arenas of work and family. Using the information presented in this chapter, providers can understand and recognize the dimensions that most positively or negatively influence a service member’s well-being and recognize gaps in service members’ well-being. Promoting well-being does not necessarily require special equipment, extensive resources, or considerable amounts of time. Well-being can be promoted and improved through simple interventions and can be used for example in the context of military health promotion frameworks like the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Total Force Fitness (see also Bowles et al., Chap. 13, this volume). Finally, influencing leaders’ awareness of and commitment to fostering an environment in which a service member can achieve optimal work–life satisfaction will improve the well-being of service members. Support for well-being by leadership can lead to a more engaged, healthy, fit and productive military workforce.

References

Adler, A. B., Bliese, P. D., McGurk, D., Hoge, C. W., & Castro, C. A. (2009). Battlemind debriefing and battlemind training as early interventions with soldiers returning from Iraq: Randomization by platoon. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 928–940.

Bar-On, R. (2012). The impact of emotional intelligence on health and wellbeing. In D. Fabio (Ed.), Emotional intelligence -new perspectives and applications (pp. 29–50). Rijeka, Croatia: InTech. ISBN: 978-953-307-838-0.

Bartone, P. T. (2017). Leader influences on resilience and adaptability in organizations. In U. Kumar (Ed.), The Routledge international handbook of psychosocial resilience (pp. 355–368). New York, NY: Routledge.

Bates, M., & Bowles, S. V. (2011). Review of well-being in the context of suicide prevention and resilience. (RTO-MP-HFM-205). Retrieved from http://dcoe.mil/Content/Navigation/Documents/Review%20of%20Well-Being%20in%20the%20Context%20of%20Suicide%20Prevention%20and%20Resilience.pdf