Abstract

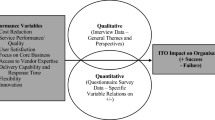

Outsourcing is broadly identified as a relevant and multi-faceted strategic choice, but, to date, its actual outcomes are still debated. Its success passes through cultural change, organizational structure and its ability to adapt. We focus on the main organizational issues arising from outsourcing choices, highlighting how managers adopt proactive techniques. We focus on the following research question: how can managers contribute to the sustainability of the competitive advantage by tackling the main organizational issues relating to outsourcing? We focus on two main categories of problems: (1) the paradoxes of outsourcing, namely the time span for the evaluation of outcomes and the effects of a multiplicity of stakeholders, and (2) the management of the ‘liminal’ effects.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Contradictions

- Economic rationale

- Externalization of work

- Liminality

- Offshoring

- Organizational identity

- Social costs

- Sustainability

- Value chain analysis

Introduction

Outsourcing is broadly identified as a relevant and multi-faceted strategic choice, but to date, its actual outcomes are still debated. It is well recognized that the success of outsourcing passes through cultural change , organizational restructuring and the ability to adapt to an extremely complex coordination . The frequency and scope of outsourcing and offshoring have increased constantly during the past twenty years, along with their popularity, which has coincided with other ‘management fashions’ (Abrahamson & Fairchild, 1999) and similar ‘bandwagons’ (Staw & Epstein, 2000), like business process re-engineering, strategic focalization, creation of shared services and corporate downsizing (Angeli & Grimaldi, 2010; De Fontenay & Gans, 2008; Gospel & Sako, 2010).

Being a multi-faceted strategic choice, outsourcing relates to structuring the entire organization in order to respond adequately to different issues. For this reason, it has been investigated by different streams of literature, such as the ones relating to: (1) strategic management (Prahalad & Hamel, 1990; Sanchez, 1995); (2) organizational approaches (Carlsson, 1994); (3) law and institutions (Domberger, 1998; Hart, 1995); (4) human resources (Leimbach, 2005; Marsden, 2004); (5) internationalization (Grossman & Helpman, 2005; Yu, 2005); (6) operations (Morroni, 1992); and (7) innovation (Van Long, 2005).

Scholarly works on outsourcing have concentrated on the motives for adopting the practice rather than on its actual outcomes and effects, debating the idea of an adoption of outsourcing practices either as a fashion and isomorphic response, or as a more rational, cost and efficiency trade-off solution. Indeed, outsourcing and decentralization do not automatically—or necessarily—lead to a more competitive organization (Lankford & Parsa, 1999).

Literature has argued that ‘contracting out might be no more than a temporary enthusiasm’ (Savas, 1993, p. 43), and has noticed that it may be the result of an institutional fashion (Clegg, Burdon, & Nikolova, 2005), or even simply a technique, functioning as myth, that may be ceremonially adopted (Meyer & Rowan, 1977) as it may be selected for efficiency criteria but in practice may deliver far less efficiency than is often claimed (Benson & Littler, 2002; Walker & Walker, 2000). Looking at adoption of outsourcing practices in the public sector, the institutional motives and rationales seem to hold even more, even as a case of mimetic isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), if we consider that contracting out of public sector activities is adopted as a technique to bring the public sector into alignment with the practices of large private business enterprises (Quiggin, 1996).

Those who favour this ‘ institutional fashion’ perspective, tend to emphasize the idea of an adoption of outsourcing practices based on mimetic, isomorphic behaviours (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), rather than efficiency arguments (Clegg et al., 2005), especially when looking at the lack of understanding and dissatisfaction (Barthelemy, 2003) by top management teams (Rothery & Roberts, 1995) of its specifics and effects. Many contributions have shown that there are several weaknesses of the outsourcing strategy (Barthelemy, 2003; Lankford & Parsa, 1999) such as the fear of losing control of activities given in trust to a third party, and risk of quality erosion, or the reluctance to share confidential or strategic data with third parties, or the difficulty of reusing human resources that can be made redundant after the transfer of some functions to outsourcing companies (Brunetta, Giustiniano, & Marchegiani, 2014). Thus, they tend to explain dissatisfaction and low performance effects of such strategies (Rothery & Roberts, 1995; Doig, Ritter, Speckhals, & Woodson, 2001; Shinkman, 2000; Macinati, 2008; Burmahl, 2000) with the idea of an adoption occurring only as an ‘institutional’ or ‘culturally valued’ phenomenon (Clegg et al., 2005).

On the other hand, a large number of studies focus on strategic motivations, such as an increased ability to focus on core activities by delegating to others activities that are considered of lower strategic importance, coupled with a potential quality increase in those activities requiring skills not available within the company, or even the possibility of acquiring more power to control activities or functions that are difficult to manage (Brunetta et al., 2014). Externalization of work at the task level through outsourcing or offshoring of work has been of interest to sociomaterial scholars (Leonardi & Barley, 2008), as social and material elements become interdependent in the process of organizing. Changes in artefacts provide people with new capabilities, changing their interaction and their reaction to change (Lommerud, Meland, & Straume, 2009).

Notwithstanding strategic motivations, economic rationales—and especially the quest for cost-efficiencies—remain the most potent tools for the promotion of outsourcing (Clegg et al., 2005), with outsourcing being adopted for activities in which the organization holds no special skills or fails to exploit economies (Brunetta et al., 2014),

Economic, institutional, strategic and financial rationales of outsourcing have thus been well documented (e.g. Giustiniano, Marchegiani, Peruffo, & Pirolo, 2014; Marchegiani, Giustiniano, Peruffo, & Pirolo, 2012), as well as some additional indirect costs, such as transaction costs (Coase, 1937; Williamson, 1989) related to contract monitoring and oversight, generation and negotiation, but also social costs, namely low morale, lower productivity (Dogerlioglu, 2012) and counterproductive anxiety (Barthelemy, 2003). Nonetheless, both the managerial practice and the extant literature still lack a set of consolidated managerial techniques capable of tackling some of the organizational issues relating to outsourcing.

Our aim in this work is to focus on the main organizational issues arising from outsourcing choices, and highlight how managers should adopt proactive techniques and play a definitive role in a company’s life. Thus, we focus on the following research question: how can managers contribute to the sustainability of the competitive advantage by tackling the main organizational issues relating to outsourcing? We specifically focus on the two main categories of problems: (1) the paradoxes of outsourcing, namely the time span for the evaluation of outcomes and the effects of a multiplicity of stakeholders , and (2) the management of the ‘liminal’ effects generated by the adoption of outsourcing practices.

The Paradoxes of Outsourcing

The link between the decision to outsource some activities and the expected structural and strategic changes should encourage the adoption of long-term and multi-actor perspectives in the evaluation of the results. The reality is, however, very different. Two kinds of paradoxes deserve further discussion: (1) the time span for the evaluation of outcomes; and (2) the multiplicity of stakeholders , which is relevant to the decisions and their implementation. Managerial techniques can therefore be applied to deal with such paradoxes.

In a world where ‘change is no longer a background activity but a way of organizational life’ (Orlikowski, 2002, p. 1) and organizational change is no longer a merely slow, incremental and cumulative process (Meyer et al., 1993), the ‘time paradox’ relates to the fact that massive reorganizations of value chain activities call for a process of organizational change that often overtakes the time spans considered for the assessment of the outcomes. Organizational literature has analysed organizational change management through different perspectives (Orlikowski, 2002), each underlining, to a different extent, the role of managers in managing change, such as literature on planned change, depicting that managers deliberately initiate and implement changes in response to perceived opportunities and thus give emphasis to the rationality of managers directing the change (Pettigrew, 1985) or literature on punctuated equilibrium that assumes change to be rapid, episodic and radical, with ‘relatively long periods of stability (equilibrium)…punctuated by compact periods of qualitative, metamorphic change (revolution)’ (Gersick, 1991, p. 12).

The search for a new way of organizing the various elements of work, for example through re-engineering, which is fundamentally a ‘rethinking and radical redesign of business processes to achieve dramatic improvements on performance ’ (Hammer & Champy, 1993) requires sufficient provision to deal with current and future requirements of the organization, but—more importantly—requires time. Organic ways of organizing arise, in substitution of traditional, hierarchical bureaucracy . In order to adapt to external change and pressure, functions are disaggregated and outsourced, in the search for an improved competitive advantage (Grey & Mitev, 1995). Thus, although companies expect the organizational settings to adapt to changes in the medium-term, the evaluation of the outcomes occurs mostly in the short-term. Lengthy evaluations and implementation processes require managers not to focus solely on short-term needs, but a long-term view of the move to outsourcing (Lankford & Parsa, 1999). The situation is even more serious when top managers believe the organizational design will automatically adapt to the new post-outsourcing setting, without inertial constraints or negative reactions. Consequently, where companies once sought order, clarity and consistency (depicted in the extant organization chart and procedures), the outsourcing of activities might engender chaotic contradictions and inconsistencies in terms of organizational goals, structures, processes, cultures and even professional identities (Latour, 2005; Smith & Lewis, 2011). An attempt to analyse issues related to the design activities and their relation to change has been made looking beyond the mere participation of managers to the inclusion of employees in the process, paying particular attention to material artefacts and to their role in making sense of change processes and work development (Stang Våland & Georg, 2014).

Social and material elements are interdependent in the process of organizing, they are, indeed, ‘constitutively entangled’ (Orlikowski, 2007, p. 1437). Indeed, changes in artefacts provide people with new capabilities, modifying their interaction and their reaction to change (Leonardi, 2013). Thus, materiality may enable outsourcing or offshoring of work at the task level (Leonardi & Barley, 2008), rather than functional level. Nonetheless, outsourcing, or offshoring arrangements often involve great disparities in the expertise at home or at the external site (Carmel & Agarwal, 2002; Lacity & Willcocks, 2001), prompting new kinds of knowledge transfer problems. This is particularly relevant when specific knowledge is embedded in artefacts and tools, requiring learning related to firm-specific work practices , needs and specifications, not just general occupational skills and knowledge.

Managerial techniques should therefore be able to deal with such paradoxical tensions (e.g. efficiency vs. efficacy, control vs. autonomy , centralization vs. decentralization) that might persist over time (e.g. Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009; Cameron & Quinn, 2006; Smith & Lewis, 2011). The unveiling of such paradoxes could contribute to the design of ad hoc techniques through a re-examination of the outsourcing phenomenon that would do justice to its inner complexity. Nevertheless, the long-term sustainability of goals depends on both short-term coordination and control of activities and the long-term maintenance of the relationships (e.g. Gittell, 2004), with both outsourcees and other stakeholders .

Thus, the idea that organizations are subject to multiple pressures is not new. In fact, any organization is subject to different groups of stakeholders , or of ‘who or what really counts’ (Freeman, 1984; Mitchell, Agle, & Wood, 1997), or ‘constituencies’ (Zammuto, 1984), and prompts us to identify a second paradox of outsourcing, which relates to the multiplicity of stakeholders.

The existence of a multiplicity of stakeholders is a consistent dimension of organizational life, and permeates any organization model and choice (Freeman, 1984; Rowley, 1997). Stakeholder theory focuses not only on an explanation of stakeholder influences on these decisions, but, since their relationships do not occur in a vacuum but rather in a network of influences (Rowley, 1997), on the multiple and interdependent interactions that simultaneously exist among stakeholders , driving tensions and influencing how organizations will operate under various conditions (Brenner & Cochran, 1991). Donaldson and Preston (1995) introduced three distinct, albeit mutually supportive, approaches to identify company stakeholders : descriptive, instrumental and normative. In particular, the descriptive approach explains the behaviours and characteristics of companies whereas the normative approach focuses on the function of the corporation and identifies the ‘moral or philosophical guidelines for the operation and management of the corporation’ (Donaldson & Preston, 1995, p. 71). Through this lens, when it comes to outsourcing, the extant literature mostly describes companies as oriented to financial and strategic goals with a minimal consideration of other relevant stakeholders ; whereas a normative approach addressing management techniques would tend towards a more inclusive consideration of all the stakeholders (e.g. including trade unions and work representatives). Because of the diversity in stakeholders ’ interests, a critical need exists to encourage managers to achieve a shared understanding among stakeholders and not only focus on responding to the self-interested goals of key organization-level stakeholders . This implies balancing expectations in response to different institutional pressures (Oliver, 1991), driven by the multiplicity of stakeholders . In other words, attempting to achieve parity among or between multiple stakeholders and internal interests, which is particularly important if external expectations conflict with organizational interests and an ‘acceptable compromise’ (Oliver, 1991) on competing objectives and expectations, may result in serving multiple interests more effectively.

The Liminal Effects

Despite the abundant amount of literature on the strategic and economic impact of outsourcing, few works have focused on the labour and worker perspectives (e.g. Brooks, 2006; Leimbach, 2005; Lommerud et al., 2009; Marsden, 2004), and most of them have focused on the social cost or the personnel issues relating to the idea that employees generally view outsourcing as an under-estimation of their skills, and counterproductive anxiety or under-commitment may arise (Barthelemy, 2003).

We focus, more specifically, on the ‘ liminality’ effects arising from outsourcing decisions, as an additional organizational issue, and trade-off, arising from outsourcing decisions. Liminality is a state of being ‘betwixt and between the original positions arrayed by law, custom, convention and ceremony’ (Turner, 1977, p. 95). In other words, a space where the regular routines of the formal organization are frozen (Sturdy, Schwarz, & Spicer, 2006), which includes temporary employees (Garsten, 1999), professionals in between different organizational identities (Zabusky & Barley, 1997) and workers who are involved in interorganizational networks and projects (Tempest & Starkey, 2004). Generally speaking, the experience of liminality is profoundly unsettling (Sturdy et al., 2006), because the known and stable organizational identities , routines and rules are dismantled, and substituted by new blurred or transitional identities, routines and norms. Nonetheless, liminality poses an interesting challenge, as it creates a space between formal institutions where cultural rules, norms and routines are not necessarily valid or applicable, thus the consistent state of fluidity might be seen as creative and even desirable (Garsten, 1999).

Some human reactions to outsourcing (of any kind of activities) are very similar to those observed by scholars who have analysed the dynamics of Information Technology (IT) infrastructure (Giustiniano & Bolici, 2012; Hanseth, 2000; Latour, 2005; Monteiro, 2000). Following David (1986), it is possible to identify some specific typical actors as:

-

Blind Giants: ‘Actors whose vision we would wish to improve before their power dissipates’ (Hanseth, 2000, p. 68). All companies’ stakeholders , including top management, can be trapped in this role when they uncritically try to favour or contrast any international outsourcing initiative and do not assess the effect of the defence of the in-house activity on the overall business of companies (‘ liminality of focus’).

-

Angry Orphans: groups of users whose routinized standards have been changed. Any employees working in an area that has any interdependence with an outsourced function could react with inertia or inefficiently to the change (‘ liminality of standards’).

The execution of outsourcing strategies could generate new organizational exigencies like gateway roles or links between internal and external parts of the same business process. Such roles could be played either by contact/interface employees or by previous employees of company A who have moved to company B, along with the outsourcing of some activities. In this context, two scenarios are of interest in terms of new managerial techniques (‘ liminality of role’): (1) employees remaining at the outsourcing company might experience significant job enrichment/impoverishment in terms of duties, coordination and control; and (2) if employees are absorbed by the outsourcee, they could suffer a temporary liminality that generates frustration and loss of individual/organizational identities .

Issues for Discussion

Outsourcing as a strategic choice for organizations experienced a widespread growth in the 1980s and 1990s. As the adoption of outsourcing practices grows, managers need a spectrum of information for the analysis of such a strategic option in order to better identify the opportunities and challenges involved with the externalization, but also to monitor decision factors relating to outsourcing.

The literature recognizes that for outsourcing to be successful the decision needs to be an informed one: while there is abundant literature on the motives for outsourcing, a more structured approach to the analysis of outcomes is being sought by managers and scholars in order to achieve stronger support in decision-making. We attempt to accomplish a deeper understanding of the outcomes of outsourcing, by identifying two main categories of organizational issues relating to the outsourcing decision, such as: (1) the paradoxes of outsourcing , namely the time span for the evaluation of outcomes and the effects of a multiplicity of stakeholders ; and (2) the management of the ‘liminal’ effects generated by the adoption of outsourcing practices.

First of all is the issue of time to evaluate the outcomes of organizational change, as managers tend to expect the organizational settings to adapt to changes in the medium-term while the evaluation of the outcomes, by different stakeholders , occurs mostly in the short-term. Lengthy evaluations and implementation processes require managers not to focus solely on short-term needs, as the new organizational solutions do not automatically adapt to the new post-outsourcing setting.

Second, the multiplicity of stakeholders surrounding the firm permeates any organization model and choice; thus the inclusion of multiple perspectives in the evaluation of outsourcing choices could be a solution to avoid unnecessary tensions and converge towards common decision processes.

Finally, the issue of liminality has been growing in the organizational literature, due to the increased attention given to the permeability of organizational boundaries, and will be taken into account when analysing outsourcing decisions, as these are likely to determine liminal spaces, which can be seen as both desirable and creative, but are traditionally considered as potentially unsettling.

Outsourcing is a business strategy and, being so, the link between the decision and the expected structural and strategic changes is tight. Managers should encourage the adoption of long-term and multi-actor perspectives in the evaluation of the results.

Although outsourcing is broadly recognized as a relevant and multi-faceted strategic choice, its actual outcomes are still debated and detailed information in the hands of management can help avoid a costly and not easily reversed choice. Effective management of the outsourcing relationships is an organizational imperative, as it is well recognized that the success of outsourcing passes through a cultural change , organizational restructuring , ability to adapt and an extremely complex coordination .

References

Abrahamson, E., & Fairchild, G. (1999). Management fashion: Lifecycles, triggers, and collective learning processes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 708–740.

Andriopoulos, C., & Lewis, M. W. (2009). Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organization Science, 20(4), 696–717.

Angeli, F., & Grimaldi, R. (2010). Leveraging offshoring: The identification of new business opportunities in international settings. Industry and Innovation, 17(4), 393–413.

Barthelemy, J. (2003). The seven deadly sins of outsourcing. The Academy of Management Executive, 17(2), 87–98.

Benson, J., & Littler, C. (2002). Outsourcing and workforce reductions: An empirical study of Australian organizations. Asia Pacific Business Review, 8(3), 16–30.

Brenner, S. N., & Cochran, P. (1991). The stakeholder theory of the firm: Implications for business and society theory of research. In Annual Meeting of International Association of Business and Society, Sundance, Utah.

Brooks, N. (2006). Understanding IT outsourcing and its potential effects on IT workers and their environment. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 46(4), 46–53.

Brunetta, F., Giustiniano, L., & Marchegiani, L. (2014). Caring more by doing less? An enquiry about the impacts of outsourcing on patient care. American Journal of Applied Sciences, 11(2), 273.

Cameron, K., & Quinn, R. (2006). Diagnosing and changing culture: Based on the competing values framework. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Carlsson, B. (1994). The evolution of manufacturing technology and its impact on industrial structure: An international study. Small Business Economics, 1, 21–37.

Carmel, E., & Agarwal, R. (2002). The maturation of offshore sourcing of information technology work. MIS Quarterly Executive, 1(2), 65–77.

Clegg, S. R., Burdon, S., & Nikolova, N. (2005). The outsourcing debate: Theories and findings. Journal of Management and Organization, 11(2), 37.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405.

David, P. A. (1986). Narrow windows, blind giants, and angry orphans: The dynamics of systems rivalries and dilemmas of technology policy. Stanford, CA: Center for Economic Policy Research. TIP Working Paper, Stanford University.

De Fontenay, C. C., & Gans, J. S. (2008). A bargaining perspective on strategic outsourcing and supply competition. Strategic Management Journal, 29(8), 819–839.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Dogerlioglu, O. (2012). Outsourcing versus in-house: A modular organization perspective. Journal of International Management Studies, 7(1), 22–30.

Doig, S. J., Ritter, R. C., Speckhals, K., & Woodson, D. (2001). Has outsourcing gone too far? The McKinsey Quarterly, 4, 24–37.

Domberger, S. (1998). The contracting organization—A guide to strategic outsourcing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman.

Garsten, C. (1999). Betwixt and between: Temporary employees as liminal subjects in flexible organization. Organization Studies, 20(4), 601–617.

Gersick, C. J. G. (1991). Revolutionary change theories: A multilevel exploration of the punctuated equilibrium paradigm. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 10–36.

Gittell, J. H. (2004). Paradox of coordination and control. California Management Review, 42(3), 101–117.

Giustiniano, L., & Bolici, F. (2012). Organizational trust in a networked world: Analysis of the interplay between social factors and information and communication technology. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 10(3), 187–202.

Giustiniano, L., Marchegiani, L., Peruffo, E., & Pirolo, L. (2014). Understanding outsourcing of information systems. In T. Tsiakis, T. Kargidis, & P. Katsaros (Eds.), Approaches and processes for managing the economics of information systems (pp. 199–220). Hershey, PA: IGI Publishing.

Gospel, H., & Sako, M. (2010). The unbundling of corporate functions: The evolution of shared services and outsourcing in human resource management. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(5), 1367–1396.

Grey, C., & Mitev, N. (1995). Re-engineering organizations: A critical appraisal. Personnel Review, 24(1), 6–18.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (2005). Outsourcing in a global economy. Review of Economic Studies, 72, 135–159.

Hammer, M., & Champy, J. (1993). Reengineering the corporation: A manifesto for business revolution. Business Horizons, 36(5), 90–91.

Hanseth, O. (2000). The economics of standards. In C. Ciborra (Ed.), From control to drift: The dynamics of corporate information infrastructures (pp. 56–70). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hart, O. (1995). Corporate governance: Some theory and implications. The Economic Journal, 105, 678–689.

Lacity, M. C., & Willcocks, L. P. (2001). Global information technology outsourcing. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Lankford, W. M., & Parsa, F. (1999). Outsourcing: A primer. Management Decision, 37(4), 310–316.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leimbach, M. P. (2005). Invited reaction: Outsourcing relationships between firms and their training providers: The role of trust. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 16, 27–32.

Leonardi, P. M. (2013). The emergence of materiality within formal organizations. In P. R. Carlile, D. Nicolini, A. Langley, & H. Tsoukas (Eds.), How matter matters: Objects, artifacts and materiality in organization studies (pp. 142–170). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leonardi, P. M., & Barley, D. E. (2008). Transformational technologies and the creation of new work practices: Making implicit knowledge explicit in task-based offshoring. MIS Quarterly, 32, 411–436.

Lommerud, K. E., Meland, F., & Straume, O. R. (2009). Can deunionization lead to international outsourcing? Journal of International Economics, 77(1), 109–119.

Marchegiani, L., Giustiniano, L., Peruffo, E., & Pirolo, L. (2012). Revitalising the outsourcing discourse within the boundaries of firms debate. Business Systems Review, 1(1), 157–177.

Marsden, D. (2004). The role of performance-related pay in renegotiating the effort bargain: The case of the British public service. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 57, 350–370.

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363.

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886.

Monteiro, E. (2000). Monsters: From systems to actor-networks. In K. Braa, C. Sørensen, & B. Dahlbom (Eds.), Planet Internet (pp. 239–249). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

Morroni, M. (1992). Production process and technical change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145–179.

Orlikowski, W. J. (2002). Improvising organizational transformation over time. In K. N. Kamoche, M. P. Cunha, & J. V. Da Cunha (Eds.), Organizational improvisation (pp. 185–228). London: Routledge.

Orlikowski, W. J. (2007). Sociomaterial practices: Exploring technology at work. Organization Studies, 28(9), 1435–1448.

Pettigrew, A. M. (1985). The awakening giant. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Prahalad, C. K., & Hamel, G. (1990). The core competences of the corporation. Harvard Business Review, 1, 79–91.

Quiggin, J. (1996). Competitive tendering and contracting in the Australian public sector. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 55(3), 49–58.

Rothery, B., & Roberts, L. (1995). The truth about outsourcing. Aldershot: Gower.

Rowley, T. J. (1997). Moving beyond dyadic ties: A network theory of stakeholder influences. Academy of management Review, 22(4), 887–910.

Sanchez, R. (1995). Strategic flexibility in product competition. Strategic Management Journal, 16, 135–159.

Savas, E. S. (1993). It’s time to privatise. Government Union Review and Public Policy Digest, 14(1), 37–52.

Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381–403.

Stang Våland, M., & Georg, S. (2014). The socio-materiality of designing organizational change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 27(3), 391–406.

Staw, B. M., & Epstein, L. D. (2000). What bandwagons bring: Effects of popular management techniques on corporate performance, reputation, and CEO pay. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(3), 523–556.

Sturdy, A., Schwarz, M., & Spicer, A. (2006). Guess who’s coming to dinner? Structures and uses of liminality in strategic management consultancy. Human Relations, 59(7), 929–960.

Tempest, S., & Starkey, K. (2004). The effects of liminality on individual and organizational learning. Organization Studies, 25(4), 507–527.

Turner, V. (1977). The ritual process. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Van Long, N. (2005). Outsourcing and technology spillovers. International Review of Economics & Finance, 14, 297–304.

Walker, R., & Walker, B. (2000). Privatisation: Sell off or sell out—The Australian experience. Sydney: ABC Books.

Williamson, O. E. (1989). Transaction cost economics. Handbook of Industrial Organization, 1, 135–182.

Yu, Z. (2005). Economies of scope and patterns of global outsourcing. Research Paper 2005/12, Research Paper Series: Globalisation, Productivity and Technology. Nottingham: The University of Nottingham.

Zabusky, S. E., & Barley, S. R. (1997). ‘You can’t be a stone if you’re cement’: Reevaluating the emic identities of scientists in organizations. Research in Organizational Behaviour, 19, 361–404.

Zammuto, R. F. (1984). A comparison of multiple constituency models of organizational effectiveness. Academy of Management Review, 9(4), 606–616.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Giustiniano, L., Brunetta, F. (2018). The Organizational Side of Outsourcing. In: Mitev, N., Morgan-Thomas, A., Lorino, P., de Vaujany, FX., Nama, Y. (eds) Materiality and Managerial Techniques . Technology, Work and Globalization. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66101-8_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66101-8_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-66100-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-66101-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)