Abstract

The authors explore the magnitude of the deindustrialisation processes in Romania, which significantly impacted the labour market, sectoral employment— mostly in industry—wages and productivity. The authors point out that, in contrast to the traditional deindustrialization pattern, in Romania, the transition, marked by the motto “haste make waste”, entailed deep and disruptive changes in terms of human values, attitudes and behavior; population; and capital loss. The authors conclude that competitiveness of certain Romanian industries is due primarily to Romania’s low wages and other labour costs rather than the result of upgrading the country’s technological level, which remains relatively low vis-à-vis other EU countries, and that this gaps is widening rather than getting smaller.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

5.1 Deindustrialization’s Effects on Employment and the Number of Employees in Industry

The phases of industrialization and deindustrialisation as reflected in the evolution of employment and the total number of employees in the economy, particularly in industry, reveal a significant gap between Romania and the other EU member states .

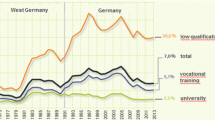

According to Eurostat data, the industrial employment in the old EU member countries started to decline in the 1960s; after 1970, and until 1990, employment in industry as a share of total employment in economy followed a rather accelerated downward slope: 43.3% to 28.7% in Belgium , 37.8% to 26.6% in Denmark , 49.3% to 40.6% in Germany , 37.2% to 33.4% in Spain , 39.2% to 30% in France , 39.5% to 32.7% in Italy and 40.5% to 37% in Austria .

Employment in the industry of the old EU member states was in the range of 20.2%–34.7% in 2010, more specifically: 25.8% in Belgium , 25.3% in Denmark , 33.5% in Germany , 22.6% in Greece , 30.8% in Spain , 26.3% in France , 28.5% in Ireland , 31.8% in Italy , 20.7% in Luxembourg , 20.2% in The Netherlands , 30.0% in Austria , 34.4% in Portugal , 27.9% in Finland , 24.4% in Sweden and 25.1% in the United Kingdom .

In Romania, the employment in industry, after having grown fourfold during 1950–1990, plunged by 2000 to less than half of what it was in 1990, (only 10 years) accounting for 25.8% of the entire labour force.

In 2015, the employment in industry in some EU Member States was as follows: 13.5% in Belgium , 21.9% in Bulgaria , 29.0% in Czech Republic , 12.6% in Denmark , 20.3% in Germany , 20.5% in Estonia , 12.1% in Ireland , 10.3% in Greece , 13.2% in Spain , 13% in France , 18.1% in Croatia , 19% in Italy , 8.5% in Cyprus , 14.8% in Latvia , 22.5% in Hungary , 16.9% in Austria , 21.8% in Poland , 17.6% in Portugal , 20% in Romania, 24.9% in Slovenia , 26.2% in Slovakia , 14.3% in Finland , 11.2% in Sweden and 10.7% in the United Kingdom .

The ratio between the number of persons employed in industry and the number of persons employed in agriculture in Romania was approximately 0.5:1 in 1999, and 0.8:1 in 2015. In 2015, the UE28 average was 3.7:1, more specifically, 11.5:1 in Belgium , 3.2:1 in Bulgaria , 9.9:1 in Czech Republic , 5.1:1 in Denmark , 14.6:1 in Germany , 5.3:1 in Estonia , 3.2:1 in Spain , 4.8:1 in France , 5.1:1 in Italy , 4.6: 1 in Hungary and in the Netherlands , 1.9:1 in Poland , 8.3:1 in Slovakia , 3.7:1 in Austria and Slovenia , 2.3:1 in Portugal , 3.4:1 in Finland , 5.5:1 in Sweden and 9.4:1 in United Kingdom .

These ratios and the developments in the past decade have widened the gap between Romania and the other member countries, creating strong economic, technical and institutional divergencies and asymmetries, rather than the expected convergence . This structure is nowadays in Romania completely disarticulated, non-functional and uncompetitive . In 2015, Romania had 22% of the active farm labourers in all of the EU 28 and only 4.7% of the industrial workers.

In Romania, the magnitude of the industrialization and deindustrialisation processes is reflected in the evolution of the number of industry employees. According to National Institute of Statistics (NIS) data, if in 1960, in Romania, approximately 1.26 million employees were employed in industry , their number increased continuously to 3.86 million in 1990, decreasing since this year to 1.87 million employees in 2000, 1.24 million in 2010 and slightly increasing to 1.33 million in 2015 (Fig. 5.1). In 2010, the number of employees in the Romanian industry was practically at the same level as in 1960.

These developments took place in the context of important changes in the architecture of the industrial sub-sectors and their repositioning in a territorial / regional profile (Table 5.1).

One of the consequences of industrial restructuring was that employers eliminated a large number of jobs as a means to achieve immediate growth in labour productivity .

Once the jobs were cut, the short-term benefits gained thereby were counterbalanced by long-term negative consequences in terms of know-how , skills , qualifications, dexterity and industrial culture in a very broad sense, which will render more difficult all future attempts at upgrading the economy.

It would be interesting to quote here the opinion of Gary S. Backer,Footnote 1 who made the observation that most often, the recovery of various peoples, in history, from wars or other disasters, was extremely fast. But, says John Stuart Mill, such recovery is fast only when those people are allowed to make use of the same knowledge and skills they had before the disaster. In a broader sense, the human capital is the carrier of know-how . When this is destroyed, when an economy loses too much of its accumulated knowledge , that economy will lack the foundation for the future accumulation of knowledge —be it be it cultural or technological—because this is the essence of economic growth.Footnote 2

The growth and development of any nation depends on how the nation valorises two basic and interdependent pillars: human capital and physical capital. Each of these two factors is capable of adjusting to the supply and demand of the particular market at hand. If we look at the evolution in history of these two pillars of society, we will notice that in the traditional economies they have brought about slow mutations, which generated a long process of adaptation and re-adaptation, both with regard to adopting the optimum response to technological changes, and with regard to allocation of resources. This process of adaptation was handed down from generation to generation.

In contrast to the traditional pattern, Romania’s precipitous transition from one type of economy to another, from one political regime to another, caused a shock wave that entailed changes that were too sudden, deep and disruptive for the Romanian society, including its knowledge , values, mentalities, behavior as well as the management of the country’s human resources and of its existing physical and natural capital.

In Romania, the need to adapt knowledge to the new economic and political context entailed huge costs, brought about a crisis of values and generated an enormous and immediate need for updated know-how , which requires slow evolution to thrive.

During 1990–2015, industry’s share in Romania’s overall employment declined from 36.9% to 22.4%. The share of industry in the total number of employees fell from 47.2% to 28.9%. The Romanian industry lost 2.5 million jobs , a number that is approximately equal to the number of Romanian citizens that had to look for employment in other labour markets, where they could not use their skills , training and versatility gained in an industrial environment. Instead they had to settle for menial jobs , such as fruit and vegetable pickers, unskilled labourers on building sites and cleaning and waste collection worker, and so on.

Practically speaking, Romanian workers who lost their jobs did not switch to positions yielding higher labour productivity compared to what they had been doing previously. Had this been so, it would have translated into a competitiveness gain for EU 28. Underusing human capital in this way resulted in a loss both for Romania and for the EU 28 as a whole; the competitive gains made from the low wages paid to Romanian workers are, in actual fact, much smaller than the potential loss of productivity .

In the extraction/mining industries , the number of jobs was reduced by 209,000 (from 267,000 in 1990 to 58,000 in 2015); the manufacturing industry released over 2.33 mil. workers; in the energy sector , the number of employees was diminished by 72,000, which was less than half of the previous number (from 127,000 to 55,000) (Tables 5.2 and 5.3).

In the period 1990–2008, the number of workers dropped by over 70% in the following sub-branches: extraction and processing of metal ores (98.6%), manufacture of textiles (87%), manufacture of machines and equipment (85.6%), manufacture of chemical products and substances (75.4%), manufacture of medical instruments (74%), coal mining and processing (73.7%) and metallurgy (72.3%).

The only activities where the number of employees increased during the period 1990–2008 were water distribution (by 9000 jobs ); publishing houses, printing and reproduction of recorded media (6000 jobs ); and waste recycling (2000 jobs ).

Between 2008 and 2015, some 270,700 jobs were lost in industry as a whole (219,500 in the manufacturing industry , 229,000 in the extraction/mining industry and 281,000 thousand in the production and supply of electricity, heating , and so on). The sub-branches that suffered most during this period were manufacturing of clothing, metal structures and metal products; metallurgy; and furniture making (Table 5.3).

The changes in the workforce with respect to numbers and structure and in the number of salaried workers in Romania point to great gaps between Romania and the other EU member states , both with regard to the rate of employment per total population and per total population of fit-for-work persons, which is considered as a target indicator in the Europe 2020 strategy , and also with regard to the share of employees in total employment.

In the case of unemployment , Romania has constantly been under the EU 28 average (with an unemployment rate of 7.6% in Romania in 2000, compared to the EU average of 8.9%, and with 6.8% in 2015, as against the EU average of 9.4% in the member states ). In 2014, unemployment rates in Austria , the Czech Republic , Denmark , Luxembourg , Malta , United Kingdom , Estonia and Germany were higher than in Romania. Despite this, after 2002, the unemployment rate among young persons has always been higher than the EU 28 average (19.8% in Romania and 19.7% in the UE 28 in 2002; 19.3% and 15.9%, respectively, in 2007; 24.0% and 22.2% in 2014; and 21.7% and 20.4% in 2015).

One of the main factors that explain the lower rates of total unemployment in Romania has been the free circulation of labour force. Free circulation of labour, in conjunction with the much lower salaries paid to Romanians in Romania, caused the loss of more than 3 million persons from the active working population of Romania, who found better earning opportunities in other EU member states .

In 1990, a total of 40.2% of Romania’s 23.2 mil. inhabitants were aged 0–24 years of age; in 2013, out of 19.98 mil. inhabitants, the age group under 24 years old accounted for only 27.2% of the a population ; during the same reference period, the share of inhabitants aged 65 and over increased from 10.4% to 16.4%. Due to these changes in the demographics of Romania, the ratio between the two age groups changed from 3.9:1 in 1990 to 1.7:1 in 2013.

In the time period 1992–2014, out of the 103 cities of major importance, called municipia, 88 declined demographically, as follows: 6 of them by 15% - 20%, 14 by 10% - 15%, 42 by 5% - 10% and 26 by 0.1 - 5%. The same depopulation process took place in other 139 cities: in 11 of them at rates of 20–45%, in 13 of them by 15–20%, in 30 by 10–15%, in 39 by 5–10% and in 46 by 0.1–5%.

The demographic depletion , and the social and economic decomposition of Romania, were triggered and fuelled by the decomposition of the industrial system. Romania’s smallest administrative divisions, the 1995 communes, recorded the following population losses: 23 of them at rates between 60% and 70%; 60 of them at rates between 50% and 60%, 87 by 40–50%, 149 by 30–50%, 420 by 20–30%, 620 by 10–20%, and 592 by 0.1–10%.

These developments have a significant impact on demo-economic balances at the macroeconomic level. In 2015, for example, out of a total workforce of 8.3 million people, only 4.6 million were salaried employees. In the same year, 5.3 million retired people were registered in Romania, out of which 4.7 million persons under the state social insurance scheme received an average monthly pension of 190 euro; 464, 000 persons, former farmers, received an average monthly pension of about 77 euro; and the others were recipients of much lower social-assistance-type pensions. The support ratio (retired persons/number of employees) recorded by Romania (1.15) is worryingly low, with some of the consequences of this situation being reflected in the severe imbalances of the state social insurance and health insurance budgets.

The collective perception of the restructuring has been and is still a negative one, meaning in particular the loss of jobs and sources of income . Granting compensatory payments to about 1.5 million people, in addition to causing chronic budget deficits and dramatically diminishing the population’s proactive attitude, has resulted in massive emigration, shortages of skilled labour and, in the absence of job supply, loss of the workforce’s self-motivation for continuous vocational education and training. In the period 1997–2005, in the context of privatisation , the compensatory payments for layoffs reached an amount, per person, ranging up to 20 gross average salaries .

In Romania, the loss of population by migration due to economic decomposition is reflected in the latest population census. The latest three of them (1992, 2002 and 2011) show that the population employed in industry decreased by 2.5 mil. persons.

According to NIS data, the official number of Romanian citizens who habitually resided abroad for more than 12 months increased from 1.48 million persons in 2007 to 2.56 million in 2014. According to the same source, 65% of Romanian emigrants are aged between 20 and 45 years and 14.5% between 46 and 59 years.

In terms of the size of non-resident Romanian communities abroad, in the EU countries, and their share in the foreign-born population of those countries, according to Eurostat data, in 2015, Italy recorded a presence of 1.15 million immigrants from Romania (first place, with 22% of the total number of immigrants in Italy), Spain recorded 595,100 Romania-born persons (first place with 15.6% of total immigrants in Spain), Germany recorded 444,200 immigrants from Romania (fourth place with 5,1% of total immigrants in Germany). Hungary had 29,700 Romania-born persons (first place with 19% of total immigrants in Hungary), Portugal recorded a number of 30,500 immigrants from Romania (8.5% of total immigrants in Portugal) and Slovakia 4,900 Romania-born persons (8.4% of total immigrants in Slovakia).Footnote 3 The picture is completed by the United Kingdom , which, in 2015, ranked Romania in fourth place among the countries of origin of immigrants, with a Romania-born population of 237,100 people.Footnote 4

The NIS census data also reveal the drastic deterioration of the age group balance: the 15–24 age group’s share of the total employed population dropped from 23.2% in 1992 to 8.6% in 2011 and that the share of employed population aged 25 to 34 years dropped from 30.4% to 24.5%; the share of persons aged 34 and over increased from 46.5% in 1992 to 66.9% in 2011. The state of things is much worse in the extraction industries, where the individuals aged 34 and over accounted for 83.3% of overall employment in 2011, and in the energy sector , where the share of the same age group had diminished from 49.4% of persons aged up to 34 years in 1992 to just one-third—17.6%—in 2011.

The reduction in the number of employees has had a severe impact on the social dialogue, its specific institutions and, last but not least, on the bargaining power of employees vis-a-vis employers .

The trade union density remains a delicate issue. While during the period 1990–1996 the inertia of the centralized economy may have been felt—in the sense that in the old political system where employees’ trade union membership was mandatory membership density was 80–90%—the deindustrialization processes, accompanied by a substantial reduction in the size of companies and number of employees, led to a significant decrease in the trade union density. A slight increase in the number of trade union members was observed in the successive years after the civil servants obtained the right to organize themselves into trade unions in 2003. At present, based on the available information, it is possible to estimate that the trade union density remains around 30% nationwide (75–80% in the public sector ).

Reforming the institutions of social dialogue according to the Law no. 40/2011, which radically changed the Labour Code and the new Law of Social Dialogue, has also led to a crisis of these institutions and actors, particularly the trade unions and employers associations, amplifying the negative effects on economic and financial issues, due to the lack of the social partner’s participation and support.

5.2 Deindustrialization, Wages and Labour Costs

A first finding is the one coming from Romania’s place among the EU member states in terms of minimum wage and average wage at European level. Since its accession into the EU in 2007, the only certainty for Romanian employees was the penultimate place in the EU member states ranking in terms of gross minimum wage , with the exception of the first semester of 2013, when Romania was last. According to Eurostat data, in 2015, the monthly minimum gross wage of approximately 218 euro in Romania was 7 times lower than in Belgium ; about 6.7 times less than that in France , Germany , the Netherlands or Ireland ; 3.6 times less than Slovenia’s , and half of the minimum wage in Poland .

In Romania, the monthly average salary, expressed in current ecu/euro, has risen slowly from 123 ecu in 1990 to 418.2 euro in 2015. In 1997, the all-economy average wage earnings have dropped to 56.2% of the 1990 value, then rose to 97.4% in 2006, 111.8% in 2007 and to 131.3% in 2014. During the economic crisis , if we take 2008 as reference year, the real wage index in 2014 was 100.8%.

The Eurostat data (Eurostat 2016) show that the hourly labour costs in companies with more than 10 employees continued to make Romania attractive for investors, but less so for the Romanian workforce, particularly youths. This data places Romania in the penultimate position (27 out 28) in the among the EU member states , with an average rate of 5.0 euro, as against 41.3 euro in Denmark , 39.1 euro in Belgium , 37.4 euro in Sweden , 35.1 euro in France and so on.Footnote 5

Another example for comparison purposes is the annual average gross wage per capita in all member states, which, in 2014, stood at approximately 10,377 euro, while in Romania, in the same year, the total annual gross wage per capita was 1941 euro, compared to 37,191 euro in Luxembourg , 22,269 euro in Denmark , 17,871 euro in Sweden , 4477 euro in the Czech Republic , 5384 euro in Estonia and 1974 euro in Bulgaria (Table 5.4).

In the period 2007–2014, the average gross salary per capita in Romania grew from 1853 euro to 1941 euro; however, this meagre growth was caused mainly by the loss of more than 1.6 mil. people; that is the population decreased from 21.565 mil. inhabitants to 19.947 mil . inhabitants (Chivu, Ciutacu, Georgescu L. 2015, 141–147).

As a matter of fact, the annual amount of gross salaries paid during the same period, in overall economy, diminished by 1.25 bn. euro (from 39.96 bn. euro to 38.72 bn. euro).

In 2014, while Romania’s share of EU 28 total population was 3.9%, only 0.7% of the total amount of gross salaries earned in the member countries was paid to Romanian workers, a figure that speaks for itself about the potential demand for goods and services, which is one of the drivers of economic growth ).

At the overall economy level, as shown, the average net monthly wage earnings expressed in ecu/euro increased from 123 ecu in 1990 to 418.2 euro in 2015 (Table 5.5

The monthly net average salaries, expressed in current euro, for industry overall, followed an ascending curve: from 111 euro in 2000, to 347 euro in 2011, and to 411 euro in 2015; in extraction and mining, the monthly net average salary rose from 184 euro, to 608 euro and respectively 777 euro in 2015; in the production and supply of electricity, from 191 to 658 euro, and respectively 692 euro in 2015.

The monthly net average salary in the manufacturing industry went up from 99 euro in 2000, to 312 euro in 2011 and to 383 euro in 2015 (Appendix A.22).

A comparison between industry, with its sub-branches, and the rise of the monthly net average salary expressed in euro shows that during 2000–2015, certain visible changes took place: in 2000, the monthly net average salary in industry was higher than the national economy average by 3.7%, while in 2015, the monthly net average salary in industry was lower by 1.7% than the national average (Ciutacu, Chivu, Dimitriu et al. 2013).

In 2015, oil and natural gas drilling were first in the classification of salaries in industrial branches and sub-branches, with a monthly net average salary of 1124 euro, which was 2.68 times higher than the national average; while in 2000, this sub-branch ranked third, with a monthly salary of 199 euro, which was 1.86 times higher than the national average (Table 5.6).

Ranking last in 2015 with respect to salaries were the food industry (281 euro and 67.2% of the national average), tanning and dressing of hides (278 euro and 66.5%), wood processing (276 euro and 66.1%) and the manufacture of clothing (265 euro and 63.3%).

The average net salaries in industry, manufacturing and the overall economy are higher in the state-owned companies than in the private sector (Appendix A.23).

In 2015, salaries in the private sector were higher than those in the public sector in the mining the oil and natural gas drilling sectors; the manufacture of clothing, paper and paper products; processing of crude oil, and manufacture of chemical products and substances.

5.3 Evolutions in Terms of Labour Productivity

As an effect of the drastic reduction of employment in industry, labour productivity expressed as the average gross value added (GVA) per employed person grew faster in Romania than the average for the EU 28 (Table 5.7).

Compared to 2005, the labour productivity per employed person in industry increased in Romania from 8600 euro to 12,900 euro in 2010, and to 21,100 euro in 2015; Romania was contributing 16% of the average labour productivity of the EU member states in 2005 and 29.7% in 2015.

It also should be noted that while in Romania the share of the workers’ pay in the GVA decreased from 53.5% in 2005, to 34.2% in 2014 and to 35.2% in 2015, in the EU 28 the rate was 54.2% in 2005 and 52.9% in 2015.

In Romania, the ratio between some of the components of GVA , particularly between compensation of employees and gross operating surplus, with the latter getting higher with time, should have prompted shareholders to invest in upgrading industrial production.Footnote 6

In 2013, for example, the all-economy expenses for compensation of employees (CE) accounted for 36% of the GVA ; the gross operating surplus (GOS) , the remaining 64%. Distributed by branches and groups of industrial products, the GOS represented 92.8% of the GVA in crude oil processing (with the CE consuming only 6.9% of the GVA ); in the food industry , the ratio between the two indicators was GOS 86.6% and CE 12.9%; in the wood products branch, the GOS was 71% and CE 28.3%; in the electricity, heating , gas, steam and air conditioning sector, the shares for the two indicators were 70% for GOS and 27.9% for CE (Table 5.8).

In 2003, the all-economy gross operating surplus represented 57.9% of the GVA , while the CE represented 42.2%; the highest share for the GOS was recorded in the food industry (71.8%), compared to a CE of only 27.2% (Appendix A.24).

Expressed in terms of gross value added to 1 euro of salary costs, labour productivity was higher in the processing industry of Romania than the average of the EU 28 by 6% in 2005, 25.5% in 2010 and 20.0% in 2013.

The highest upper differentials of labour productivity in Romania versus the EU 28 were recorded in 2010, in the manufacture of other, non-metallic, products (2.1 times); wood processing and manufacture of wooden products (1.73 times in 2010 and 1.7 times in 2013); manufacture of electrical equipment (1.44 times in 2010 and 2013); and manufacture of machines, machinery and equipment (1.35 times in 2010 (Table 5.9).

The apparently higher competitiveness of Romanian industry was, in fact, the result of the low salaries paid to Romanians, which caught the immediate interest of foreign investors , rather than the result of investing in the upgrading the technical and technological level of the industrial infrastructure . In the manufacturing industry as a whole, the share held by Romania in the overall gross value added created in the member states grew from 0.5% in 2005, to 0.8% in 2010 and 0.9% in 2013.

In 2013, Romania contributed 1.4% to the GVA of the EU 28 in the manufacture of motor vehicles (as against only 0.43% in 2005), 5.2% to the GVA in the manufacture of apparel, 2.18% to the manufacture of footwear and 2.1% and1.60%, respectively, to the GVA in the wood processing and manufacture of furniture sectors.

Notes

- 1.

See Backer (1997, 381).

- 2.

See also Rodrik (2015).

- 3.

Migration and migrant population statistics, Eurostat, 2017 (http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics).

- 4.

See Rienzo and Vargas-Silva (2015).

- 5.

Eurostat, Estimated Hourly Labour Costs, 2016. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/File:Estimated_hourly_labour_costs,_2016_(EUR)_YB17.png

- 6.

On capital-income ratio, see the model and analysis of Thomas Piketty 2013: Le Capital au XXI siècle, Seuil, Paris.

References

Backer, Gary. 1997. Human Capital—A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with a Focus on Education [Capitalul uman—o analiză teoretică şi empirică cu referire specială la educaţie]. Bucharest: Editura ALL [Publishing House].

Chivu, Luminiţa, Constantin Ciutacu, and Laurenţiu Georgescu. 2015. Consequences of Wage Gaps in the EU. Procedia Economics and Finance 22: 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00244-0.

Ciutacu, Constantin, Luminiţa Chivu, Raluca Dimitriu, and Tiberiu Ţiclea. 2013. The Impact of Legislative Reforms on Industrial Relations in Romania. International Labour Office, Industrial and Employment Relations Department; ILO DWT and Country Office for Central and Eastern Europe.

Eurostat. 2016. Estimated Hourly Labour Costs. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/File:Estimated_hourly_labour_costs,_2016_(EUR)_YB17.png

Migration and Migrant Population Statistics. 2015. Eurostat. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics

Piketty, Thomas. 2013. Le Capital au XXI siècle. Paris: Seuil.

Rienzo, Cinzia, and Carlos Vargas-Silva. 2015. Migrants in UK: An Overview. The Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, 2015 Edition. http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/sites/files/migobs/Migrants%20in%20the%20UK-Overview.pdf

Rodrik, D. 2015. Premature Deindustrialization. NBER Working Paper, No. 20935, Cambridge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Chivu, L., Ciutacu, C., Georgescu, G. (2017). Impacts of Romania’s Deindustrialization on Labour Market and Productivity. In: Deindustrialization and Reindustrialization in Romania. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65753-0_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65753-0_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-65752-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-65753-0

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)