Abstract

Adverse events or outcomes are unwelcome occurrences. Unfortunately, adverse events will likely occur sometime during the physician’s lifetime in the practice of medicine. The possibility of such an event should be taken into account when planning and discussing treatment. Patients should be advised about the possibility of adverse events during the process of informed consent. An adverse event may occur despite all appropriate precautions being taken by the treating physician, but some adverse events are clearly preventable. An adverse event may trigger a malpractice action by a patient or patient’s family. This chapter will discuss the informed consent process, adverse events, malpractice claims, and the physician’s role in documentation and disclosure. The information that has been provided in this chapter is based on a review of publications on the subject. It should not be construed as legal advice. If as a healthcare provider you are involved in a legal case, get the direct advice of a risk manager or a lawyer.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adverse events or outcomes are unwelcome occurrences. Unfortunately, adverse events will likely occur sometime during the physician’s lifetime in the practice of medicine. The possibility of such an event should be taken into account when planning and discussing treatment. Patients should be advised about the possibility of adverse events during the process of informed consent. An adverse event may occur despite all appropriate precautions being taken by the treating physician, but some adverse events are clearly preventable. An adverse event may trigger a malpractice action by a patient or patient’s family. This chapter will discuss the informed consent process, adverse events, malpractice claims, and the physician’s role in documentation and disclosure. The information that has been provided in this chapter is based on a review of publications on the subject. It should not be construed as legal advice. If as a healthcare provider you are involved in a legal case, get the direct advice of a risk manager or a lawyer.

Informed Consent

In general, the elective procedures described in this textbook are performed only following a doctor-patient discussion about that treatment and the associated complications that might ensue. Every adult patient has the right to make decisions about his or her healthcare. That decision must be an informed decision.

The concept of informed consent is a relatively new idea in the history of Western medicine. As far back as the time of the writing of the Hippocratic Corpus in Greece during the fifth and fourth century BC, physicians were instructed to “attend to the patient with cheerfulness and serenity … revealing nothing of the patient’s future or present condition” [1]. It was not until the twentieth century that the concept of informed consent was formulated and developed into a widely recognized and applied conversation between the doctor and patient that recognized the patient’s need to know [2].

Much of the discussion about the more recent evolution of informed consent is based on legal case history, which has framed current thinking of informed consent as a right of patients based on ethical principles. This is understood as a principle that is based on the autonomy of the individual and of individual freedom of choice [3]. These ethical principles have been codified by many professional medical organizations. A code of ethics adopted by the American Board of Neurologic Surgery called for “open communication with the patient” and requires that “medical or surgical procedures shall be preceded by the appropriate informed consent of the patient” [4]. Informed consent has also come to be viewed as an obligation which may enhance the doctor-patient relationship. The recently adopted code of medical ethics outlined by the American Medical Association describes informed consent in this way: “Informed consent to medical treatment is fundamental in both ethics and the law. Patients have the right to receive information and ask questions about recommended treatment … Successful communication in the patient-physician relationship fosters trust and supports shared decision making” [5].

What are the elements of informed consent? Informed consent should include an adequate discussion of what is involved in the procedure, in other words, what will happen during treatment. It should include a discussion of the expected benefits and the risks or complications that can occur with that treatment. Finally, it should also include a discussion of alternative treatments, including the alternative of no treatment and the risks and benefits of these other options.

A key early case, often cited as a cornerstone in the development of the legal concept of informed consent, is a 1914 New York Supreme Court decision, Schloendorff v. Society of New York Hospital [6]. Mary Schloendorff was admitted to the hospital with a “stomach disorder.” The treating physician diagnosed a fibroid tumor and recommended surgery. She consented to an examination under ether which she was told would be needed to better characterize the tumor, but she refused surgery to remove the tumor. While she was unconscious, the tumor was removed, and she suffered a complication of the surgery. The court found that “Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body; and a surgeon who performs an operation without his patient’s consent commits an assault for which he is liable in damages.” Subsequent cases involving consent were often brought as assault and battery cases and focused more exclusively on the idea that the patient had to consent to the procedure not whether they were well informed. Today cases based on battery are generally limited to situations where there was no consent obtained, a different physician performs the procedure than the patient was led to believe was going to perform the procedure, or the procedure performed is substantially different than the one the patient consented to [7].

The idea of informed consent was first used in a landmark 1957 case Salgo v. Leland Stanford Jr. Univ. Board of Trustees [8]. The patient in this case, Martin Salgo, agreed to aortography, and the procedure was complicated by permanent lower extremity paralysis. Mr. Salgo, his wife, and his son all testified that they were not given any information about the nature of the procedure, and the treating physicians admitted that the patient had not been apprised of any risks of the procedure [9]. Among the instructions given to the jury, the judge specified that a physician had a duty to disclose to a patient “all the facts which mutually affect his rights and interests and of the surgical risk, hazard and danger, if any” [9].

Informed consent generally moved from cases considered under the legal delineation of battery to that of negligence. The legal definition of negligence is “a failure to behave with the level of care that someone of ordinary prudence would have exercised under the same circumstances. The behavior usually consists of actions, but can also consist of omissions when there is some duty to act” [10].

A defining case in the move to considering lack of adequate informed consent as a matter of negligence is a case decided in 1972 by the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, Canterbury v Spence [8]. Jerry Canterbury was a minor who suffered from back pain and saw a neurosurgeon working at the Washington Hospital Center, Dr. William Spence. Dr. Spence recommended that Canterbury undergo a laminectomy for a suspected ruptured disk. He did not disclose that there was risk of permanent neurologic deficit from the operation to the patient or his mother. He was asked by the patient’s mother if the surgery was dangerous and chose merely to say “not any more than any other operation” [11]. The patient suffered a complication and had permanent difficulty walking, urinary incontinence, and bowel paralysis. The appellate court found that Dr. Spence had been negligent and that the physician was required to divulge risks that a “reasonable person” would “attach significance to” [11].

Failure to obtain informed consent prior to a procedure can be the basis of a malpractice action. The cornerstone of this claim is that the physician withheld information that would have led the patient, acting as a reasonable person, to not consent to the procedure. What is the standard that physicians are held to in order to decide that they have withheld crucial information? States are essentially split between a “physician-based” standard and a “patient-based” standard. In a jurisdiction that applies the physician-based standard, there is a requirement that physician disclose information which a reasonable physician would disclose. When a state uses a patient-based standard (also known as material risk standard), the physician’s disclosure should include the information that an objective patient would consider material.

Who should obtain the informed consent? The simple answer is the physician or member of the physician’s team that is considering performing the procedure for which the consent is being obtained. In complex procedures, if other physicians are performing portions of the procedure, those individuals should obtain separate consent. For instance, in an anterior approach spine surgery, when the general or vascular surgeon is performing the exposure procedure, that physician should consider the need to obtain informed consent regarding his/her portion of the procedure.

There are certainly circumstances which the law recognizes are exceptions to the obligation a physician has to obtain informed consent. These include an emergency situation, a circumstance which would dictate that there is common knowledge about the risk, and when the physician is aware the patient has prior knowledge of that risk [8]. In an emergency situation, the physician may act without the expressed consent of the patient if the patient is unable to consent. In general, it is preferable to obtain consent from family members if possible, but if there is no time, to proceed with treatment [8]. The two criteria that should be met to have a medical emergency preclude the need for informed consent are that the patient is incapacitated and that a life-threatening situation requires urgent treatment [7].

Adverse Events and Malpractice

An adverse event has been defined as “an injury that was caused by medical management, rather than the underlying disease” [12]. An adverse event or injury does not in and of itself constitute grounds for malpractice. Clearly some complications occur despite the physician performing and managing an indicated procedure in an acceptable fashion with proper safeguards in place. These events are known to occur and are discussed at the time of informed consent as recognized risks. In essence, they are not preventable. For example, aneurysm rupture is a known complication of surgical clipping and endovascular coiling and may occur even in the best managed circumstance. When an adverse event is however due to an error, it is a “preventable adverse event ” [13]. Errors have been classified as “active” when they are due to the direct actions of a healthcare worker or “latent” when there is a systemic problem causing the error which may be related to issues arising from the facility, equipment, or organization [14].

In order for an adverse event that has caused an injury to meet the legal definition of malpractice, four criteria must be met which come under the broad terms of duty, breach, causation, and damages [15]. The physician has to be shown to have a duty to care for the patient, in other words that there is a physician-patient relationship. Assuming that relationship exists, the physician’s duty is to “possess and bring to bear on the patient’s behalf that degree of knowledge, skill and care that would be exercised by a reasonable and prudent physician under similar circumstances” [15]. The second criterion to be met is that there was a breach of that duty. Most malpractice cases are brought for negligence. Negligence is often evaluated as a standard of care question. In a malpractice case, the issue of what a reasonable and prudent physician would have done under similar circumstances or what was the standard of care would be decided with expert opinion. The third criterion that must be satisfied is causation , in that the physician’s negligence was the cause of the injury. This relationship has the legal term “legal cause” or “proximate cause ” [16]. It requires that the negligence be a “substantial factor” causing the injury, not necessarily the only or major cause of the injury [16]. Finally, the physician breach needs to result in damages or a loss to the patient which generally results in recovery of damages through a monetary award. Damages can be awarded for physical, emotional, or financial loss. Damages are classified as “general” when they are for issues like pain and suffering or grief. They are classified as “special” damages when they are related to medical costs of current and future care and loss of income.

Malpractice claims are unfortunately quite common in the United States. A survey of claims against physicians through a single large nationwide insurance carrier during a 14-year period ending in 2005 showed that in any given year, 7.4% of physicians had a claim against them [17]. There was a marked variation in that percentage depending on subspecialty, with high-risk specialties generally being the procedure-based surgical specialties. Neurosurgeons had the highest rate, with 19.4% having a claim in any given year, and psychiatrists having the lowest rate at 2.6%. Estimates of cumulative risk suggested that by the age of 65 years, 75% of physicians in low-risk specialties would be sued, while in high-risk specialties, 99% of physicians would be sued [17]. Although there are a large number of claims filed, the same study showed that 78% of claims did not result in payment to the claimant. Additional recent data does suggest that the rate of claims being paid has generally declined from 1994 to 2013 [18].

Documentation

In tangible terms, when there is a litigation, the question is not if something occurred but if it can be proved that something occurred. Documentation of the informed consent discussion with the patient should be part of the medical record. Most hospitals require that there be a signed consent form in the medical record before a procedure is performed. Hospital licensing organizations and state licensing agencies require hospitals to have informed consent policies, and hospitals can share in the liability if the physician has not obtained informed consent [19]. However, getting the consent form signed is not a substitute for obtaining informed consent. Some consent forms will only include a description of the proposed procedure and the physicians performing that procedure. Often the signed consent form will only contain a nonspecific comment about risks, benefits, and alternatives being discussed. In some legal jurisdictions, the form is presumptive evidence that a full discussion occurred, and the burden of proof lies with the plaintiff to prove that adequate consent did not occur [8]. However, it is often recommended that the physician enters a separate note into the medical record that documents a full discussion occurred with the patient [16]. It is also suggested that this note should include a discussion of the major risks and those that are the most serious [16]. Commentators suggest, depending on the nature of the procedure, the note would look something like: “Risks discussed with patient included but were not limited to, infection, bleeding, nerve/nervous system damage, damage to adjacent organs, paralysis, stroke and death.”

Disclosure

At the core of any discussion about disclosure lies the ethical obligation that physicians have to their patients. Modern medical ethicists have routinely called for physicians to disclose errors to patients [20, 21], and major medical societies have strongly supported this policy. The Principles of Medical Ethics of the American Medical Association calls truthful and open communication between doctor and patient “essential for trust in the relationship and respect for autonomy” [5]. It specifically tells physicians they should “disclose medical errors if they have occurred in the patient’s care.” The Joint Commission also advocates that accredited hospitals inform patients when an adverse event has occurred, endorsing that “the licensed independent practitioner responsible for the patient’s care, or his or her designee, discloses to the patient and family any unanticipated outcomes of care, treatment, and services” [22].

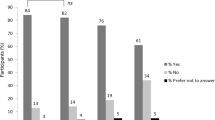

Despite these entreaties, there appears to have been a mixed reaction in the physician community to the actual reporting of errors. This is highlighted by a relatively recent study which queried a large number of US and Canadian physicians by survey [23]. It found that 98% of physicians agreed that a serious medical error should be disclosed but that number dropped to 74% when a minor error was involved. The study also found that 74% of the physicians felt that disclosure of a serious error would be very difficult. In addition, 21% said that if the patient was unaware that the error happened, they would be less likely to disclose the error, and 19% said they would be less likely to disclose an error if they thought the patient was going to sue.

At the crux of the physician, concern about disclosure is the exposure to legal risk. Some organizations, generally smaller self-insured hospital systems, have adopted a full disclosure policy which includes an apology and remediation for an error [24,28,25,12,10,2,23,6,17,22,9,1,13,11,26]. These organizations have suggested that a full disclosure policy with an accompanying apology can actually result in reduction of claims and have shown this within their hospital systems. A clear connection between disclosure and the increased likelihood of a legal action has not been established [27]. However, potential concerns still exist and are reflected in the legal arguments against offering an apology [28]. The possible hazards to apologizing include a concern that the apology could actually trigger a legal action by painting the picture that there is an easily winnable case. Perhaps, more important is the argument that in most jurisdictions an apology can be entered into evidence and may be used as an admission of guilt [28]. In addition, a conflict with the insurance company could exist from either disclosure or apology since malpractice policies often have a clause requiring the insured entity to cooperate with efforts to defend against a legal action [28].

The conflict between the need to disclose errors and the possible hazards of disclosing those errors is far from resolved. As some authors have suggested, the current malpractice model which names physicians as targets of fault may have to be replaced with a system based on no fault or the liability of the entire healthcare organization [29]. Perhaps as physicians move into a model of employment by a healthcare entity and away from private or small group practice, this will become an easier goal to achieve. At the present time, however, recommendations like that of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for disclosure are being made: “It is important to understand the difference between expressions of sympathy (acknowledgement of suffering) and apology (accountability for suffering). Expressions of sympathy are always appropriate. The appropriateness of an apology, however, will vary from case to case. When considering whether an apology is appropriate, the physician should seek advice from the hospital’s risk manager and the physician’s liability carrier” [30].

Conclusion

Every adult patient has the right to make decisions about his or her healthcare. That decision must be an informed decision. Obtaining informed consent is vital to the physician–patient relationship. Informed consent should discuss the expected benefits and the risks or complications that can occur with treatment. It should also discuss alternative treatments, including the alternative of no treatment and the risks and benefits of these other options. With an open and clear discussion, physicians can help to minimize misunderstandings and potential legal action should an adverse event or complication occur. Finally, if an adverse event occurs, the physician should consider consulting risk management for support and advice.

References

Katz J. Informed consent-must it remain a fairy tale? J Contemp Health Law Policy. 1994;10:69–91.

Dolgin JL. The legal development of the informed consent doctrine: past and present. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2010;19(1):97–109.

Patterson R. A code of ethics. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:271–7.

American Board of Neurologic Surgery. Code of Ethics. 2016. http://www.abns.org/en/About%20ABNS/Governance/Code%20of%20Ethics.aspx/. Accessed 30 July 2016.

American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics. 2016. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics.page. Accessed 28 July 2016.

Hathi Trust Digital Library. The Northeastern reporter. 2016. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044103146437;view=1up;seq=114. Accessed 24 July 2016.

Svitak L, Morin M. Consent to medical treatment: informed or misinformed? William Mitchell Law Rev. 1986;12(3):540–77.

Moore G, Moffett P, Fider C. What emergency physicians should know about informed consent: legal scenarios, cases and caveats. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:922–7.

Justia. Salgo v. Leland Stanford etc Bd Trustees. 2016. http://law.justia.com/cases/california/court-of-appeal/2d/154/560.html. Accessed 24 July 2016.

Cornell University Law School. Negligence. 2016. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/negligence. Accessed 24 July 2016.

Louisiana State University Law Center. Consent and Informed Consent. 2016. http://biotech.law.lsu.edu/cases/consent/canterbury_v_spence.htm. Accessed 24 July 2016.

Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, Hebert L, Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Newhouse JP, Weiler PC, Hiatt HH. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370–6.

Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999.

Rolston J, Bernstein M. Errors in neurosurgery. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2014;26:149–55.

Sanbar SS, Warner J. Medical malpractice overview. In: Sanbar SS, Firestone MH, Fiscina S, LeBlang TR, Wecht CH, Zaremski MJ, editors. Legal medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007. p. 253–64.

Sheuerman D. Medicolegal issues in perinatal brain injury. In: Fetal and neonatal brain injury. 4th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. p. 598–607.

Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):629–36.

Mello MM, Studdert DM, Kachalia A. The medical liability climate and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2014;312(20):2146–55.

Pope TM, Hexum M. Legal briefing: informed consent in the clinical context. J Clin Ethics. 2013;25(2):152–75.

Banja J. Moral courage in medicine—disclosing medical error. Bioethics Forum. 2001;17:7–11.

Smith ML, Forster HP. Morally managing medical mistakes. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2000;9:39–53.

Joint Commission. Patient Safety Systems Chapter for the Hospital program. 2016. https://www.jointcommission.org/patient_safety_systems_chapter_for_the_hospital_program. Accessed 3 Aug 2016.

Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Garbutt JM, Kapp JM, Chan DK, Dunagan WC, Fraser VJ, Levinson W. US and Canadian physicians’ attitudes and experiences regarding disclosing errors to patients. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(15):1605–11.

Bell SK, Smulowitz PB, Woodward AC, Mello MM, Duva AM, Boothman RC, Sands K. Disclosure, apology, and offer programs: stakeholders’ views of barriers to and strategies for broad implementation. Milbank Q. 2012;90(4):682–705.

Boothman RC, Blackwell AC, Campbell DA Jr, Commiskey E, Anderson S. A better approach to medical malpractice claims? The University of Michigan experience. J Health Life Sci Law. 2009;2(2):125–59.

McDonald T, Helmchen L, Smith K, Centomani N, Gunderson A, Mayer D, Chamberlin WH. Responding to patient safety incidents: the “seven pillars”. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):e11.

Robbennolt JK. Apologies and medical error. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(2):376–82.

Block. Disclosure of adverse outcome and apologizing to the injured patient. In: Sanbar SS, Firestone MH, Fiscina S, LeBlang TR, Wecht CH, Zaremski MJ, editors. Legal medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007. p. 279–84.

Banja JD. Problematic medical errors and their implications for disclosure. HEC Forum. 2008;20(3):201–13.

American Colleg of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Disclosure and discussion of adverse events. 2016. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Patient-Safety-and-Quality-Improvement/Disclosure-and-Discussion-of-Adverse-Events. Accessed 3 Aug 2016.

Acknowledgments

This chapter greatly benefited from the input of David Sheuerman, JD, who provided helpful suggestions before the chapter was written and editorial comments of the draft of the chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Marks, M.P. (2018). Medicolegal Aspects of Complications. In: Gandhi, C., Prestigiacomo, C. (eds) Cerebrovascular and Endovascular Neurosurgery. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65206-1_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65206-1_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-65204-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-65206-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)