Abstract

Introduction: While we understand the potential benefits of mothers and fathers singing to their infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), the process is not simple. The challenges can be personal, contextual, and temporal. Singing is not a natural action for everyone. With rapidly increasing individualized music listening technology and decreasing opportunities for active music making in many countries, people have less experience and awareness of their own musicality. This can hinder their capacity to use music as part of nurturing their infant. Additionally, across their time in the NICU, parents can feel concerned about singing in a “public” place.

Main aims: This chapter outlines how the music therapist works in the real-world lived experience with parents. Three phases – anticipatory, cautious interplay, and active parenting – offer parents a different range of potential for their voice and the unfolding relationship with their infant.

Conclusion: The music therapist works with mothers and fathers to reconnect them to their own vocal potential and to normalize the sound of singing in the NICU. These processes are underpinned by theories of attachment and infant neurodevelopment and are responsive to the evolving needs of the mother and infant.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

The everyday lived experience of people is never as tidy as the findings of research studies convey. Even in experience-near qualitative research (Frogget & Briggs, 2012) which allows the reader to share in the experience of the participant, the descriptions are still orchestrated by the researcher to illustrate a predetermined point. Real life in the NICU is not so linear, but a “roller coaster” (Layne, 1996), during which families treasure the “normal” things like touching, holding, feeding, and washing.

While singing may not always be on that list of normal things, using the voice is. Families talk to their infants, regardless of whether they know their infant is aware or not (Shoemark & Arnup, 2014). This vocal potential is a simple but vital indication of parent role and status in their infant’s well-being. We are familiar with the portrayal of families in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) feeling that they are both figuratively and literally without a voice. They are characterized as displaced, powerless, and without a voice in their infant’s life. In reality, the scope of parenting experience also includes those parents who demand a pivotal role as advocate and voice for their infant, creating partnerships with nursing and medical teams to promote their infant’s care and experience. The therapist in the clinical context must hold this scope in mind so no assumptions are made about the inner or outward expressions of the family’s experience.

It is important to note that the role of the music therapist will depend on the culture of the country, the region, the hospital, the ward, and the music therapist (Shoemark, 2015). Each influences the acceptable theoretical premise and implementation of the actual intervention. This chapter is provided by an Australian music therapist with 20 years’ experience in a pediatric NICU, informed by a preceding practice in special education and early intervention. The writing will reflect that experience, while also drawing in other known perspectives. There is also a movement to acknowledge fathers in the NICU, and the lived experience of singing in the clinical context pertains equally to fathers as mothers. Therefore, the term “parent” is used instead of mother to build the precedent for the inclusion of fathers.

Most music therapists working in the NICU take referrals from other NICU team members. For some staff, peer-reviewed evidence of the effect of singing may be needed before they will refer, but when parents and bedside nurses clinically observe change in the infant or parent to music therapy, this will usually provide sufficient evidence of effect to engender referrals. The team will be willing to refer infants and families for music therapy even when their understanding of the process is quite limited. Beyond individual team members, embedding music therapy in the standard clinical pathway for infants and families is reliant on the individual music therapist’s capacity to articulate the mediating pathway in a manner which is congruent with the culture of the NICU.

Depending on the music therapist’s training and theoretical framework, singing becomes an intervention or a strategy, when it is brought into the parent’s consciousness within the therapeutic relationship. In a family-centered model , the music therapist creates a partnership with the parent by first understanding the parent’s status in their life trajectory (Perry Black, Holditch-Davis, & Miles, 2009), alongside their evolving experience of parenting and their own musical self (Shoemark & Arnup, 2014). By first calling to consciousness the parents’ own capacities to generate an optimal presence, parents can begin to find a comfortable use of their voice and singing and integrate it into their day with their infant. In other NICU cultures where the NICU team member is still considered to be the expert, the family might be able to put aside their own uncertainties to follow the stipulated intervention.

Parents Actually Singing in the NICU

The modest research about parents singing live in the NICU has identified the primacy of the mother’s voice for NICU infants. Dearn and Shoemark (2014) identified the significance of maternal presence in the NICU even when they were very passive, and recent research has begun to report the significance of the primacy of parental voices as optimal stimulus (Filippa, Devouche, Arioni, Imberty, & Gratier, 2013; Loewy, Stewart, Dassler, et al., 2013).

Before singing might be considered as a viable experience for families, availability and use of voice serves as a starting point. We understand that parents who believe that singing is useful or can think of a reason for singing in the NICU are likely to go on and use their voices to sing to their baby (Shoemark & Arnup, 2014). So the music therapist can first gently inquire about the parent’s beliefs and knowledge, to ascertain the probability of singing. While the person introducing the idea of singing obviously has a belief in the usefulness of such action, there should be no assumption that any parent shares this belief. On this basis, the discussion about singing should never actually begin with singing. The discussion should begin with the most likely existing use of voice, talking. If the music therapist has observed the parent talking to their infant, then affirmation is the starting point, “I can see you are already talking to your baby, that’s lovely.” Where there is no possibility of observing the parent talking to their infant, then the music therapist asks, with an expectation that the parent has been talking (Shoemark & Arnup, 2014). This question affords the therapist the opportunity to bring to the parent’s consciousness their experiences of talking to their baby. Where a parent reveals they are not talking, the music therapist understands that there is a rupture to the parent’s sense of self and the program must proceed cautiously to reconstruct that parent’s sense of self in relation to their infant while also referring back to a mental health team if there is one.

The act of singing is revealing and potentially embarrassing, and without understanding the parent’s proclivity for singing, it is not likely that a parent will actually sing (Blumenfeld & Eisenfeld, 2006). The capacity to sing may be moderated by a lack of musical heritage. Singing in the NICU is possible for parents who can think of a reason or imagine singing but is also made possible by their own experience of being sung to as a child and their own experiences of playing/learning an instrument or playing and singing in an ensemble (Shoemark & Arnup, 2014). The music therapist accounts for these factors, when initiating contact with parents.

The everyday lived experience of music is rapidly changing. Like others, parents perceive that music making is something undertaken by recording artists. As active music education is discarded from the education systems, the opportunities for becoming musical are also diminishing in high-income countries. It is not unusual for parents to report that they cannot sing. The music therapist reframes this perception by inquiring gently about everyday singing experiences, most commonly singing along to a recorded music source while in the car or shower or while doing house work. This often allows parents to realize that they actually do sing and thereby overcoming their reluctance.

When introducing singing as an intervention, it is important to consider that the experience of singing is not a singular phenomenon but occurs in and across time. Singing is a temporal process which both takes time and creates time for “being” together (Shoemark, 2017). It takes time to sing the chorus of a song, to hum a verse, and to recite a nursery rhyme. Within that bounded time of a song, there is opportunity. A song creates a time in which parent and infant can be engaged in the same experience of contingency or reciprocity (Trevarthen & Malloch, 2000; Trehub, Plantinga, & Russo, 2015) and potentially a significant moment of meeting (Tronick, 1998) or synchrony (Feldman, Magori-Cohenc, Galili, Singerb, & Louzounc, 2011). Song is a time-bound pattern of replicable expectation, joy, and memory building:

Everything gets interrupted by medical ... there’s always someone at the door. Having a program like this [music therapy] that everyone understands could help parents to make that time happen….”Footnote 1 Kyra

Across the time of the NICU admission, a parent’s opportunities for singing can be organized loosely into three time frames. The first phase is anticipatory , when the infant is not available for interplay because of medical instability or sedation and the role of the parent is constrained to a simple presence and limited sensory support. Once the infant has stabilized and is socially available but restricted by their condition or complex care regimes, the parents enter a phase of cautious interplay , in which they are unsure about what they can do. Finally is the phase of active parenting , in which the infant may have periods of medical stability and social availability and parents focus on opportunities for development.

Anticipatory

The early days of NICU admission are usually marked by functional and technical medical care serving to stabilize or maintain stability of the infant’s physical status. During this time, neurological immaturity, sedation, intubation, and analgesia may prevent the infant from being available to his parents in ways they might have expected or hoped for. The loss of role is profound. This can immediately undermine a parent’s identity as primary nurturer, knowing simply how to be with their infant, while for some, it inflames a fierce determination to protect and advocate for their infant as a baby:

I know. I’ve seen, I’ve had Liam on machines breathing for him… when they’re not available, all you might get is the occasional eye open and that always caught me because that’s something the machines can’t do, that’s him…Which is why I read to him. That’s what I did, that’s all I had. In the end I had hope and to let him know that I’m here. Just keep going…. It was hard, but I just had go ‘Alright, regardless, I'm just going to be there’. He needs to know I’m going to be there for him. Jo

During this time, the music therapist may partner with the parents to be witness to the baby’s simplest capacities and to help parent understand their baby’s behavioral cues and the potential of their own expression:

If we’d known how important our voices were, and she’s still going to love us and know who we are by our voices rather than touch, it would have made me feel a lot better. Ann

Knowledge is often key at this point, giving parents enough reason to continue their presence and actions even when there is no obvious response. As needed, the music therapist introduces key information about what is known about infant auditory processing, the difference between ambient sound and the detectable stimulus of voice, recognition of parental voice, and answering all and any questions parents ask. A further strand of the discussion acknowledges the infant’s inability to obviously respond at this time. For some parents, a discussion about how their infant’s heart rate and oxygen saturation can indicate their response to stimulation is an accessible pathway to understanding their baby’s experience. However, as far as possible, the purpose of family-centered practice is to humanize and maintain a meaningful connection between parent and infant, so singing is a human act of nurturing care, not medical care. The focus remains on the parent’s direct experience of their baby’s response or complete lack of response to their presence and action.

Where an infant is unable to respond at all, the music therapist can work with parents to help them hold the potential of their baby in mind. This can be achieved by encouraging parents to see their efforts as storing experience in their baby’s brain and “heart.” The prospect that their loving care and interaction might be processed by their infant in a way which we do not yet understand is usually enough to sustain a parent when there is no obvious response from their infant.

In the anticipatory phase, the parents may note that they would use their voice, but because their infant is unavailable, they have not talked at all or much. The music therapist can introduce the possibility that the sound of the parent’s voice is at least useful and at best critical for their infant’s ongoing brain development which will usually override any sense that it serves no purpose.

Once the usefulness of voice is established, many parents will spontaneously discuss other voices use such as reading, humming, singing, or prayer. This opens the discussion about acceptable voice use and promotes the potential for leading the parent toward the idea of singing or patterned voice use. Patterned voice use is any kind of speech in which a replicable pattern may be developed. This most commonly includes (a) little rhymes which may be a familiar part of the family heritage shared with other siblings or in own childhood and (b) chants which are little phrases of comfort such as “there, there, there” or “sh-sh-sh” repeated for soothing the infant.

The music therapist may demonstrate any and all possibilities to the parents, to confirm they have understood the action as intended but also to give labels to new actions as actual supportive strategies. Mothers often note that they use chant but do not necessarily think of this as a conscious action, despite it being the most common way in which any adult soothes an infant. The categorization of this little action as a strategy helps parents claim their role as the pivotal person who knows intimate details about their infant and enables them to inform other carers such as nurses about this action as a successful strategy.

Because of the acute environment , many parents do not want to make any more noise, and most will whisper to their infant (Shoemark & Arnup, 2014). Whispering does not contain a melodic contour, and therefore the intention of the message is lost to the infant (Spence & Freeman 1996). The music therapist will demonstrate whispering and quiet talking, and parents almost always detect the loss of the melodic content in the whispering. The parent immediately understands that voiced sound is needed to make their intention clear to their baby.

In some music therapy practice, it might also be that the music therapist first creates musical sound in that anticipatory phase so that parents can experience the sound without being responsible for it. The song of kin (Loewy et al., 2013), which is a song selected by the parent for its familiarity and comforting, is adapted to a closely contained form of lullaby (3/4 or 6/8 time, slow repetitious, breathy) to create a supportive auditory experience which is shared by all within hearing. Where opening their mouth to sing might feel too revealing, the parent might be able to hum. The creation of such moments of intimacy can provide pivotal support for parent as nurturer.

Cautious Interplay

Infants with complex medical needs can provide the greatest challenge for their parents. Conditions which cause ongoing pain or discomfort, treatments which limit positioning or scope of movement, and regimes which include nasogastric, nasopharyngeal, or orogastric tubes can all compromise or distort infant’s capacities to achieve regulation and interact with their parent or carer. The capacity of the infant to respond may vary greatly both in actual behavior and in the time it takes (see below in Active Parenting for more discussion on this). The infant’s windows of availability may be brief and infrequent, and the cues they give may be idiosyncratic to their medical condition or their emerging personality. Despite perplexing responses, parents are eager to maximize the window of availability and can unwittingly be overwhelming to hospitalized infants. They can be very anxious about every nuance of behavior or seemingly oblivious to significant cues. At either extreme, their infant can withdraw, complain, or outright protest. In units where a family-centered approach is lacking, less than optimal parental interaction may cause the parents to feel judged:

“We were told not to over-stimulate her and then when she woke up we were like”ooh-ooh Taylor…..“[demonstrates very excited, big smiling face] and the nurses were like "leave her alone”!” Tyra

The music therapist works in partnership with parents to understand their baby’s thresholds for stimulation and the behaviors that indicate tolerance, acceptance, and engagement:

Vignette: As Shelley approaches Tyron’s bed, she is already talking to him brightly, “good morning bubba, your Mama is here”. She touches his cheek, strokes his head, runs her hand down his torso, and pats his tummy. Tyron looks at her brightly and stretches his legs and arms out tight, then turns away, taking several minutes before he returns. Shelley is disappointed, “don’t you wanna talk to me today?”

Shelley interprets Tyron’s response as disinterest or, worse, rejection; when in most cases, this response is more likely to be a disengagement from the overwhelming variety of stimuli Shelley offered. The therapist can help Shelley to be aware that she brings sight, sound, smell, touch, and sometimes vestibular action, without necessarily thinking about how overwhelming that presence might be. The music therapist helps her to identify that this disengagement is about Tyron’s tolerance for stimulation and not an indication of his interest in her. On arrival, Tyron recognizes her voice, so while she washes her hands, she can talk to him to give him an opportunity to gently alert to her presence and prepare for when he subsequently sees her. This sort of incremental transition will also allow the parent’s space to observe their baby’s availability for interaction allowing both parties a gentler and often more successful start to interplay.

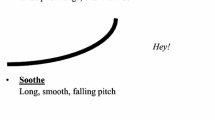

The infant’s capacity to be engaged may be short-lived, and the change from engaged to disengaged can come without obvious warning. Pain, discomfort, hunger, or physical restriction (intravenous drips, mittens, tubes, etc.) can impinge on the infant. Also, for some infants, conditions such as Pierre Robin syndrome are associated with frequent periods of protracted irritability. The “zero to ten” shift into distress or seeming anger can leave parents confused, powerless, and feeling betrayed. The music therapist can demonstrate and work with parents to help them understand the power of their voice in that moment to preempt or even momentarily override escalating distress. By understanding and controlling the pitch, timbre, and tempo of their voice, parents can create a low, steady, flat intonation to reassure their infant that escalating distress is not needed (Shoemark & Grocke, 2010).

It is important to help parents understand that meaningful sound and interaction are about taking turns or an even more rudimentary balance of sound and silence. Without silence, sound becomes noise. For the anxious or intrusive parent, a problem can arise when they think that if they’re not making a sound, they’re not doing something:

My husband and I are do-ers…. so we find it very hard not to do something. It’s hard to get your head around [giving space] because we feel as though we’re not helping or we’re not being worthwhile… Ann

To sit quietly during the sought-after periods of infant availability can be counterintuitive. So rather than telling parents to stop or wait for a response, it can be more helpful to encourage them to create a space for their infant. To create a quiet space in which their infant can answer them makes sense to the active parent :

I think she’s missing out on because she’s asleep so much, that I might actually need to just give her space in that awake time and if I am being too intense with her then she might just go back to sleep rather than stay awake.” Karla

Voice use and singing in this phase can still emulate the sounds and singing for soothing (as offered in the anticipatory phase) to encourage transition to sleep or a quiet awake state for other interactions. Understanding the characteristics of a lullaby is not difficult for parents. They can readily imagine that a lullaby is quiet, slow, and gentle. The value added at this point is helping parents see the impact of changing any and all of the elements of music one at a time. For parents with musical heritage (instrument learned, choir experience), this can be readily achieved, using musical terminology drawing on mastery in other parts of life. For the parent without musical heritage, this is introduced through demonstration and shared experience. The music therapist helps parents to hear and sing a little quieter, a little breathier, a little slower, etc. By singing a song over and over, the parent will also embed this song in the memory of the nurse caring for their infant, and on departure it might just be that the nurse will return to that song if the baby stirs.

Alongside this, playsongs can now be added to promote more active interplay in the available infant. These are discussed in the next section where they are even more pertinent.

Active Parenting

During the NICU admission, the infant may be medically stable and developmentally more available for interplay. Such opportunities might occur while infants await surgery or diagnosis or toward the end of the admission. The purpose of singing now becomes to acknowledge the “good enough” baby (Winnicott, 1971) whose potential as a developing baby now comes into focus.

Parents , now mindful of scaffolding their baby’s experiences so they do not overwhelm, can add the bright and joyful playsong during active interplay. Playsongs are identifiable by their bright and clipped timbre, their faster tempo, regular pulse (4/4 time), and the introduction of rhythmic interest. These are the songs that parents imagined singing at home. They create experiences of tangible happiness. The parent’s fatigue and ongoing stress often impinge on their capacity to remember even the best known songs of their own childhood. The music therapist helps a parent to recall a selection of songs and, where appropriate, calls on extended family for suggestions which in turn creates a wider context for songs to be shared. Because playsongs are more characterful and expressive, this can be a time when a parent’s embarrassment or lack of confidence may override their inclination to sing:

I’ll do it when I get home. I just feel stupid doing it in a hospital. Hailey

If we were in a room by ourselves it would be a lot better. If I had my earphones or I knew some nursery rhymes or something I might. Sandra

The music therapist may resource the family with simple playlists of constructed renditions of songs that provide a “soundtrack” to which they can sing along. Singing along with a recording is a familiar, everyday experience which also provides some masking for their shared experience.

Song becomes a vehicle by which parents can shape the day. This is drawing them toward the regular everyday use of music at home (Ansdell & DeNora, 2016), casually singing a familiar song, while drying their toes, and humming a little tune while settling into feeding or to sleep. The music therapist helps parents to find their creativity, making up songs to label their experiences:

We just make up random stuff [laughs]. I must say my husband sings more than I do. He’s sung a few songs. I think it was quite funny; he started off with nursery rhymes and then made up bits at the end. I don’t know if he couldn’t remember the words or just put his own spin on it. He actually tends to do more of the singing and the reading than I do. Ann

During the song, parents can also construct opportunities for the rehearsal of motor and communication skills. A parent’s song creates an unspoken but predictable duration to any task, whether it is bathing or physical therapy. For communication, the music therapist helps parents to understand turn-taking through musical games and a repertoire of songs which promotes vocalization, protoconversation, and joyful creative expression.

It is worth noting that singing in the NICU is not always about the infant and parents’ emerging life together. When an infant has a life-limiting condition, families can be eager to create memories with their baby. The music therapist may use singing and a song to create shared experiences to be treasured. Amidst anticipatory grief, songs can serve as an accessible and recognizable experience, providing a legacy that is easily recalled. It is unlikely that the parent will be able to sing through the emotion of this moment, so the music therapist metaphorically holds infant and parents together, singing for them all in the moment of the song.

Singing to create a legacy might occur in the days or weeks leading up to an infant’s death, but the music therapist can also create a warmer auditory context via songs and other music during final extubation from ventilator support and even in the hours after death. For the infant’s funeral, the music therapist may record or actually play requested songs to celebrate the joyful moments of the baby’s life. The experience of singing together and the song serve as symbols of the baby as baby, leaving behind the complexities of their medical condition.

Conclusion

The music therapist works in partnership with parents to understand their preexisting relationship with music and their current capacities to utilize singing to nurture and support their baby. The music therapist facilitates the parent’s psychological access to their voice, as a tool for infant containment and soothing, as an enticement into interplay, as a vehicle for development, and as a meaningful memento when needed.

Key Messages

-

The usefulness of singing in the NICU can be conceptualized in three phases: anticipatory, cautious interplay, and active parenting.

-

There should be no assumption that singing is a viable action for parents in the NICU.

-

The music therapist brings to consciousness in the parent their own current use of voice and supports ways in which that action can be extended.

-

To actually sing in the NICU, a parent must first be able to think of a reason or imagine singing to their infant in hospital.

Notes

- 1.

All names are changed. All quotes are drawn from the study reported in Shoemark, H. (2017).

References

Ansdell, G., & DeNora, T. (2016). Music and change: Ecological perspectives: How music helps in music therapy and everyday life. London, UK: Routledge.

Blumenfeld, H., & Eisenfeld, L. (2006). Does a mother singing to her premature baby affect feeding in the neonatal intensive care unit? Clinica Pediatricas, 45, 65–70.

Dearn, T., & Shoemark, H. (2014). The effect of maternal presence on premature infant response to recorded music. JOGNN, 43, 341–350.

Feldman, R., Magori-Cohenc, R., Galili, G., Singerb, M., & Louzounc, Y. (2011). Mother and infant coordinate heart rhythms through episodes of interaction synchrony. Infant Behavior & Development, 34, 569–577.

Filippa, M., Devouche, E., Arioni, C., Imberty, M., & Gratier, M. (2013). Live maternal speech and singing have beneficial effects on hospitalized preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica, 102(10), 1017–1020. doi:10.1111/apa.2013.102.issue-10

Frogget, L., & Briggs, S. (2012). Practice-near and practice-distant methods in human services research. Journal of Research Practice, 8(2.) Retrieved from http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/318/276

Layne, L. (1996). “How’s the baby doing?” Struggling with narratives of progress in a neonatal intensive care unit. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 10, 624–656.

Loewy, J., Stewart, K., Dassler, A.-M., et al. (2013). The effects of music therapy on vital signs, feeding, and sleep in premature infants. Pediatrics, 131, 902–918.

Perry Black, B., Holditch-Davis, D., & Miles, M. (2009). Life course theory as a framework to examine becoming a mother of a medically fragile preterm infant. Research in Nursing & Health, 32, 38–49.

Shoemark, H. (e-pub 2017). Time Together: A feasible program to promote parent-infant interaction in the NICU. Music Therapy Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/mix004

Shoemark, H. (2015). Culturally transformed music therapy in the perinatal and paediatric neonatal intensive care unit: An international report. Music and Medicine, 7(2), 34–36.

Shoemark, H., & Arnup, S. (2014). A survey of how mothers think about and use voice with their hospitalized newborn infant. Journal of Neonatal Nursing, 20, 115–121.

Shoemark, H., & Grocke, D. (2010). The markers of interplay between the music therapist and the medically fragile newborn infant. Journal of Music Therapy, 47, 306–334.

Spence, M., & Freeman, M. (1996). Newborn infants prefer the maternal low-pass filtered voice, but not the maternal whispered voice. Infant Behavior and Development, 19, 199–212.

Trehub, S., Plantinga, J., & Russo, F. (2015). Maternal vocal interactions with infants: Reciprocal visual influences. Social Development. doi:10.1111/sode.12164

Trevarthen, C., & Malloch, S. (2000). The dance of wellbeing: Defining the musical therapeutic effect. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 9(2), 3–17.

Tronick, E. (1998). Dyadically expanded states of consciousness and the process of therapeutic change. Infant Mental Health Journal, 19, 290–299.

Winnicott, D. (1971). Playing and reality. London, England: Tavistock.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Shoemark, H. (2017). Empowering Parents in Singing to Hospitalized Infants: The Role of the Music Therapist. In: Filippa, M., Kuhn, P., Westrup, B. (eds) Early Vocal Contact and Preterm Infant Brain Development . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65077-7_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65077-7_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-65075-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-65077-7

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)