Abstract

Rural areas are frequently envisioned as non-changing and homogeneous communities immune to the difficulties associated with modern urban life. In this chapter, we first explore some of the powerful stereotypes of rural communities that have influenced the development of social and health policy in the past century. Second, we try to show the diversity among rural environments and its importance in mental health policy and service development. Third, we identify potential processes and structures by which public mental health services may be organized. The Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1963 in the United States is reconsidered as an effort to develop a locally controlled mental health system, and recent infrastructure consistent with the Affordable Care Act in the context of schools is discussed. Because educational systems are a common institutional presence in most, if not all, rural areas, they provide reasonable and potentially equitable vehicles for thoughtful, context-driven mental health service collaboration and delivery for children and families.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Key words

The adjective “rural” is used to describe a kaleidoscope of cultural, economic, geographical, institutional, and demographic patterns. Although many attempts have been made to define what is meant by “rural,” enormous differences, even within regions of the same country, characterize rural communities and their people and history. Yet, rural areas are frequently thought to be a monolithic culture and environment, often defined and described simply as a non-urban default. As urbanization dominated demographic trends in the twentieth century, rural environments appeared to be treated as if they had melded together into one non-metropolitan land mass.

It is not surprising, then, that government and social policy would be dominated by urban concerns. During the urbanization of the last century, many people concentrated in metropolitan communities, leaving fewer people in the expansive rural landscapes. Stereotypes of pastoral and protected rural environments, along with the dominance of urban populations, influenced mental health policy and service development in the twentieth century and continue today. But, rural areas have changed and are changing; they are no longer, if they ever were, consistent with many of the earlier stereotypes, resulting in a different perspective of the needs of the people who populate its communities .

In this chapter, we, in part, point out some of the powerful stereotypes of rural communities that have influenced the development of social and health policy in the past century. Second, we demonstrate the enormous diversity among rural environments and its importance in mental health policy and service development. Third, we identify potential processes and structures by which public mental health services may be organized. In an effort to be responsibly responsive to rural public mental health needs, the Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1963 in the United States is revisited as a model for a locally controlled mental health system. Because educational systems are a common institutional presence in rural areas, they provide reasonable and potentially equitable vehicles for thoughtful, context-driven mental health service collaboration and delivery, particularly for children and families. Finally, we recognize some of the realities of the “new” rural that has emerged from the twentieth century.

Stereotypes of Rural Environments

Among the most significant of the stereotypes is that rural areas are all alike. However, there is no commonly held definition of “rural” among government agencies or scholars studying the rural environment. Apparently, then, a number of variables and dimensions are considered when attempting to define the rural environment. As a result, the diversity among rural communities is rarely documented or appreciated. For example, a variety of federal agencies in the U.S. employ a range of classification systems to identify rural areas primarily based upon population density . According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2015), all areas that are not classified as Urbanized Areas (50,000 or more people) or Urbanized Clusters (less than 50,000 but more than 2500 people) are rural. The Office of Management and Budget offers a slightly more refined classification of areas, defining regions as Metropolitan, Micropolitan, or neither. Metropolitan areas contain an urban hub of 50,000 or more people, whereas Micropolitan areas contain an urban hub of less than 50,000 but at least 10,000 people. The classification of rural, again, remains a default category (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015).

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) uses a dimensional system for classifying areas on a scale from 1 (urban/metropolitan) to 9 (most isolated rural) based on population and proximity to metropolitan areas. The Office of Rural Health Policy, similarly, considers the level of a given community’s “rurality” on a continuous basis, classifying individual census tracts using the Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes that consider population density as well as commuting direction and distance to urban hubs (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). Similar to the definitions in the U.S., Australia utilizes a variety of classification systems, both categorical and dimensional, to identify rural remote and metropolitan areas with consideration of population density and accessibility to service centers (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016). Although these systems codify geographical areas, they imply uniformity among rural areas and fail to capture the diversity among rural communities.

Despite a wide range of rural environments, mental health policy historically has either ignored rural needs or lumped rural areas together, as if they are all the same. Stereotypes of rural people and places appear to dominate the development of public mental health care, often rendering service delivery and administration ineffective and irrelevant. Stereotypes include the peaceful, pastoral nature of rural environments; the unchanging characteristic of the rural demography and landscape; the fundamentally agrarian nature of rural economies; and a monolithic perspective among rural areas across the world. Reality does not, however, always cooperate with the idyllic connotations of rural communities. Noted below are examples of the significant diversity among rural environments.

Population Changes

Rural areas are often thought of as constant and stable. Throughout the past few decades, the demographic patterns of rural areas in the United States have changed considerably (Johnson, 2006, 2012). As of 2010, about 15% of the United States population was identified as residing in non-metropolitan areas, a considerably smaller percentage compared to past populations, with significantly less population gain relative to the 1990s (Johnson, 2012; USDA, 2014). Overall, population decreases relate to fewer births and lower migration into rural areas, as well as the out-migration of young adults into urban areas to seek employment. Population changes in rural areas are, however, far from uniform. For example, the majority of rural areas proximal to metropolitan areas and rich in natural amenities and recreational resources (e.g., the mountains and coastal areas of the U.S.) evidenced population growth, although the growth was less than in the 1990s (Johnson, 2012).

On a local level, rural communities are rarely described as ethnically diverse; however, the migration of non-Caucasian minority groups has been responsible for a substantial amount of non-metropolitan population growth since 1990 (Johnson, 2006, 2012). Specifically, as of 2010, 3.8 million inhabitants of rural America were identified as Hispanic, accounting for approximately 5% of the total rural population. Importantly, twenty-first century rural counties have experienced an overall increase in Hispanic youth (45% gain) and a simultaneous decrease in non-Hispanic White youth (10% decrease). Counties with a majority of minority children are concentrated in the Mississippi Delta, the Rio Grande area, the Southeast, and the Northern Great Plains (Johnson, 2012).

Poverty

Poverty rates in the U.S. consistently have been higher in non-metropolitan compared to metropolitan areas since first recorded in the 1960s. Although the economic gap between metropolitan and non-metropolitan has fluctuated across time and improved with growth in the 1990s, non-metropolitan areas of the U.S. have evidenced slower recovery from the 2007–2009 recession compared to urban areas. The poverty gap between non-metropolitan and metropolitan appears to be widening; the 2011 poverty rate in non-metropolitan areas increased 1.6% points from 2010, whereas the metropolitan area poverty rate decreased slightly (USDA, 2014).

Similar to general poverty levels, U.S. rural child poverty rates are reliably higher than urban child poverty rates, affecting one fourth of rural children in 2014 (USDA, 2015). Poverty among children is recognized as an important gauge of short- and long-term outcomes in physical health, language and cognitive development, academic achievement, and educational attainment, as well as mental, emotional, and behavioral health (Yoshikawa, Aber, & Beardslee, 2012). Childhood poverty is also associated with increased morbidity and decreased life span in adulthood (Blane, Bartley, & Davey-Smith, 1997; Lawlor, Ronalds, Macintyre, Clark, & Leon, 2006).

Although not unique to rural children, cognitive abilities and subsequent school achievement outcomes differ between poor and non-poor children (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997). Impoverished children are significantly more likely to experience both learning disabilities and developmental delays than non-poor children (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997; Emerson, 2007). Relatedly, economically disadvantaged children are more likely to drop out of school, repeat grades, and demonstrate lower math and reading achievement. Lower academic achievement relates to parental education and family structure, which have a bidirectional relationship with poverty levels (Vernon-Feagans, Burchinal, & Mokrova, 2015).

Impoverished children are also more likely to suffer from emotional and behavioral problems compared to non-impoverished children (Moore, Redd, Burkhauser, Mbwana, & Collins, 2009). Poor children are more likely to experience internalizing and externalizing problems such as aggression, fighting, acting out, anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal (Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, 1994; Emerson & Hatton, 2007) and report high levels of stress and demonstrate lower levels of stress-regulation (Evans & Kim, 2007). Poverty, then, frequently is found to be a more relevant variable than rurality.

Education

High school graduation rates are similar in rural and urban areas of the U.S. (National Center for Education Statistics, 2013); however, potentially consistent with stereotypes, rural individuals earn fewer degrees and complete fewer years of schooling (Gibbs, 1998; Provasnik et al., 2007) than urban residents. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (2013), persons 25 years and older from urban areas have greater higher education attainment, with 32.9% earning a bachelor’s or higher degree compared to 20.8% of rural individuals.

Multiple barriers may contribute to lower educational attainment among rural youth such as greater poverty, lower parental education attainment and expectations, and poorer high school preparation in rural compared to non-rural areas (Roscigno & Crowley, 2001; Roscigno, Tomaskovic-Devey, & Crowley, 2006). Likewise, a less broad school curriculum and limited access to career counseling and college preparatory programs, which may be more common in rural schools, impact students’ decisions to attend college (Graham, 2009; Griffin, Hutchins, & Meece, 2011; Lapan, Tucker, Kim, & Kosciulek, 2003; Monk, 2007; Provasnik et al., 2007). Earlier age of marriage and pregnancy, as well as traditional societal roles (Olgun, Gumus, & Adanacioglu, 2010; Timaeus & Moultrie, 2015), may also relate to lower educational attainment in rural areas.

Economy

Another common rural stereotype is that of a primarily agrarian economy . In the past, agriculture was the main driving force in the rural economy. Farming does dominate the economy of roughly 403 out of 2151 rural counties in the United States, yet only about 6.5% of rural Americans engage in farming. Although small family and individual farms account for the majority of rural farming, corporate farming has decreased employment opportunities and contributed to the increased migration of young adults to urban areas in search of employment opportunities (Johnson, 2012).

Overall, manufacturing has replaced agriculture as the primary market for the rural labor force. In 2003, about 12.4% of rural individuals were employed in manufacturing compared to 8.4% of their urban counterparts. However, recent globalization of manufacturing jobs has diminished employment opportunities for the rural labor force (Johnson, 2006).

Similarly, mining, including oil and gas extraction, has historically been a major employer in rural areas (Johnson, 2006). Mining is still a force in 113 out of 2151 rural counties across the United States (Johnson, 2012), despite negative environmental and psychosocial correlates (National Resources Defense Council, n.d.; Sangaramoorthy et al., 2016). Fracking chemicals and debris released into water systems and air as well as fracking-related earthquakes negatively impact the natural environment in many rural areas . Additionally, oil and gas production have been linked to an amplified risk of health issues such as cancer and birth defects (National Resources Defense Council, n.d.).

Another economic contributor in rural areas is the prison system. A push for private prison-building in rural areas of the U.S. occurred in the 1990s as an attempt to stimulate economic growth (Beale, 1996; Huling, 2002). In 1994, 402 rural counties housed a prison compared to only 135 counties in 1969 (Hooks, Moser, Rotolo, & Lobao, 2004). The outcome research is inconsistent regarding the impact of prisons on rural areas. Some researchers found that prisons created new employment opportunities (Donzinger, 1996) and others suggest that prisons provide only small economic stimulation as they require specialized operation needs that are difficult for rural businesses to sustain (Hooks et al., 2004).

While the majority of rural labor markets have experienced decline over the past century, tourism and retirement opportunities have contributed to economic growth in many rural communities. Rural counties offering recreational and retirement opportunities have grown consistently from the 1970s to the early 2000s, consistent with the corresponding influx of older adults (Johnson, 2006, 2012).

Crime

Perhaps not surprisingly, and somewhat consistent with stereotypes, crime rates are lower in rural compared to urban communities (U.S. Department of Justice, 2011). Rates are often categorized based on types of crime and include violent crimes (e.g., murder, manslaughter, rape) and property crimes (e.g., burglary, larceny, vandalism). Estimates of crime in the U.S. in 2010 suggest that violent crime was substantially higher in urban communities (428.3 per 100,000 inhabitants) compared to rural areas (195.1 per 100,000 inhabitants). The same pattern is seen in property crimes in the U.S. (U.S. Department of Justice, 2011), and comparable rural-urban differences are found in the United Kingdom (Department for Environment, Food,, & Rural Affairs, 2012).

Although reported crime rates appear lower in rural areas relative to urban areas, these rates are likely influenced by community resources as well as interpersonal fears associated with reporting and prosecuting which may be greater in smaller, less anonymous, rural communities (Berg & Lauritsen, 2015; Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), 2012). For example, in the U.S., in 2012, rapes known to law enforcement did not differ between non-metropolitan and metropolitan area counties; however, arrests for rape in the U.S. during this same year were almost twice as common in more populated areas compared to less populated areas (FBI, 2012). Limited resources in rural communities may negatively impact police productivity (Weisheit, Falcone, & Well, 1994). Technological infrastructure, potentially compromised in rural relative to urban areas, may contribute to delayed crime reporting and maintaining national crime databases (National Institute of Justice, 2004, 2010).

Impact of Stereotyping Rural Environments

Beliefs that rural environments lack diversity result in the development of mental health policy that is irrelevant for the reality of rural life. The idea that the rural economy is essentially agrarian, for example, limits the economic base on which local mental health services can be developed and sustained. Certainly, some rural areas are grounded in agrarian economy, but many others are not.

The diversity of available mental health professionals in rural areas also influences the nature of the public mental health system. Some rural areas adjacent to or containing resort opportunities may well have an abundance of professional services, whereas small communities that dot the landscape away from those opportunities may not have such professional resources. Public mental health systems that are based on local involvement necessarily will reflect the nature of those communities.

The Reality of Rural Diversity

Definitions of “rural” based on population density and proximity to urban areas fail to capture the fact that rural environments differ substantially from one another. History, immigration patterns, demographic characteristics, sociocultural development, prevailing weather conditions, and economic and political factors forge variable environments that underlie differences. Frequently, ethnic characteristics of a given area explain attitudes toward male roles in families that become important in economically hard times. For example, the eastern European heritage in the Great Plains underlays the tendency toward suicide when farms failed during the farm crisis in the 1980s. Because of the geographical expanse in the Great Plains, even local mental health services were distributed over enormous areas, frequently causing difficulty of access for those who needed them. While the nation’s midsection suffered from the farm crisis of the 1980s, the non-agriculturally based rural areas were not hit so hard (Gunderson et al., 1993; Walker & Walker, 1988).

Although most rural areas share some core features (e.g., poverty, relative isolation), there is not a universal rural culture. Relative to mental health services, however, rural areas lack availability of services, accessibility of services, and acceptability of services (Mohatt, Bradley, Adams, & Morris, 2005). Even when mental health services are available, they are often underutilized by rural residents, likely as a result of accessibility to services and acceptability of services (Aisbett, Boyd, Francis, Newnham, & Newnham, 2007). Driving time to mental health services, challenging weather and road conditions, limited public transportation, and lack of insurance or limited insurance may make it difficult to access mental health services even when available. In addition, available and accessible services may not be utilized if perceived as unacceptable or culturally uninformed. For example, social stigma and negative attitudes toward seeking help as well as concerns about confidentiality in a small community may render accessible support unwelcome (Mohatt et al., 2005).

In the case of mental health services, in rural as well as non-rural areas, it is not enough to merely understand current diagnostic criteria, theories of etiology, and evidence-based practice. Rural areas differ widely in terms of migration history and acculturation, language, religion and spirituality, traditions and beliefs, economy, weather, transportation, community life, and many other factors that constitute the fairly poorly understood and often non-articulated, but critically important, concept of culture. Alarcón (2009) argues for the importance of considering individualized cultural explanations for both the origin and process of “getting ill,” noting that investment in understanding the cultural context is necessary for accurate diagnosis and effective intervention.

In order to aid in useful diagnosis and to develop, implement, and responsibly adapt and test evidence-based behavioral interventions , tools must be developed to reflect the inherent diversity of rural communities. The DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) includes a Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI; patient version and informant version), influenced by medical anthropology (e.g., Kleinman, 1988), designed to assess the client’s idiosyncratic and culturally informed understanding of presenting problems, coping and resources, and help-seeking that may prove useful to rural mental health services. The intention of the CFI is to help clarify presenting problems, strengthen the therapeutic alliance, and inform psychoeducation and intervention. Evidence to date on the utility of the CFI is limited; however, a pilot study suggests that the CFI facilitates effective communication via rapport-building and facilitation of the client narrative in service of clinical utility and client acceptability (Aggarwal, Desilva, Nicasio, Boiler, & Lewis-Fernández, 2015). The CFI and other culturally informed assessment systems increase the likelihood of interventions that will be less reliant on stereotypes and more effective.

Implications for Mental Health Service Delivery

The differences among rural environments influence the development of accessible and acceptable community mental health services. Policies and procedures that work in some areas are ineffective in others. The first time that these differences were recognized in mental health legislation in the U.S. was in the Community Mental Health Centers (CMHC) Act of 1963. This landmark mental health legislation may represent the zenith of public mental health services in the U.S. The CMHC Act organized a complete system of mental health care in the country that was based on “catchment areas” that include urban, suburban, and rural populations. It also lodged responsibility for the governance of programs in the catchment areas themselves. A balanced responsibility for mental health services that brings together federal, state, and local resources enhances the likelihood of local ownership and the responsiveness of the citizenry. Federal and state standards coordinated with local resources and input more likely insures programming that is consistent with and acceptable to the local population. This act, brainchild of the John F. Kennedy presidency, likely was the first time that rural people were intentionally included in the planning, administration, and delivery of mental health care in the U.S.

Under the CMHC Act , the country was divided into catchment areas that included populations that could not exceed minimum and maximum requirements. These divisions respected state boundaries and were done in collaboration with state authorities for mental health services. The requirement was that the entire state’s population was included in the plan and local communities and neighborhoods were given responsibility and authority to develop and maintain mental health care. As a result, some urban areas had several community mental health catchment areas and some rural areas covered large geographical expanses to include the required population base. The authority to govern the programs was given to each catchment area and they were initially mandated to provide five essential services, including outpatient, inpatient, consultation, partial hospitalization, and 24 h emergency availability. Additionally, CMHCs were required to have four core professions represented on their staffs (i.e., psychiatry, psychiatric nursing, social work, and psychology). Paraprofessional workers were encouraged but not required.

The makeup of the catchment areas presented a variety of challenges for the planning and development of mental health programs in both rural and urban areas. Economic forces, ideological perspectives of government-provided mental health service, political divisions in local neighborhoods and communities, professional alliances, the relationship between some existing state mental health care and local communities, and existing consumer advocacy groups all played into the development of the CMHCs. Several challenges were faced by the rural catchment areas. First, they included vast distances that were involved to reach minimum population requirements. Second, they required community mental health planners and staff to relate to a wide variety of collateral agencies and multiple jurisdictions, frequently with different policies and practices. Third, they frequently involved communities that sustained bitter economic rivalries and histories. Fourth, few rural communities were able to attract qualified professional persons who would meet the requirements of the law.

Nevertheless, the CMHC Act provided rural communities the opportunity to design, within service and staffing constraints, community mental health services that could be responsive to their own needs. It was the opposite of the top-down placement of public mental health services onto the local communities. States have variably responded to the provision of mental health services in their jurisdictions. In some states, community mental health centers have retained the balance of local, state, and federal support through available mechanisms. In others, systems have changed. The important contribution of the CMHC Act of 1963 was its emphasis on the tripartite sources of support and regulation.

Embedded in the CMHC Act was the principle of cooperation among federal, state, and local governments. The Act was initiated at the federal level and required states to have well-documented plans for the development and maintenance of community mental health programs. Local communities, defined by the catchment area specifications, were to have local boards representing the communities of the region, serving to administer service delivery agencies, and providing the connection to local governing boards in cities and counties. The designated state mental health agency had the responsibility of assuring that community boards were appointed and given sufficient authority to carry out the mandate of federal legislation.

Unfortunately, political and professional concerns led to the erosion of the CMHC Act and it never was realized in the way that President Kennedy visualized. The underlying assumption that rural residents were connected to urban hubs and had access to acceptable, available services was not realized (Blank, Fox, Hargrove, & Turner, 1995). Facility-based mental health services, limited in their availability and accessibility, appear not well-suited to the realities of the rural environment. Rather, rural mental health services may be better utilized when integrated into existing organizations such as general healthcare (e.g., primary care, emergency rooms), churches, workplaces, and schools. In addition, increased community capacity to address mental health needs with non-specialists, including paraprofessionals, may help address the availability, accessibility, and acceptability of assistance with mental health and behavioral health problems (Blank et al., 1995).

Separated by more than a decade, the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment report, Health Care in Rural America (1990), and the 2003 President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health similarly revealed significant disparities in access to culturally competent mental health services for residents of rural communities when compared to their urban counterparts. Evaluations of the behavioral health workforce indicate an acute shortage of service to children and families as well as rural communities (Annapolis Coalition on the Behavioral Workforce, 2004), suggesting the need to expand community capacity as well as strengthen and support a professional workforce. Mental health disparities, especially in areas marked by lower socioeconomic status, are apparent not only in the U.S., but across the globe (Becker & Kleinman, 2013).

Barriers to behavioral health services experienced in rural areas (i.e., availability, accessibility, and acceptability) relate to lower rates of seeking healthcare and adhering to treatment (Mullins & Chaney, 2013). Given school-aged children are legally required to attend school or document equivalent access to education, school-based mental health programs hold great promise for addressing the barriers of availability and accessibility. The potential for decreased stigma-related concerns (e.g., not being seen at a mental health clinic) and culturally responsive programs that question rural stereotypes (Owens, Watabe, & Michael, 2013) increases the potential of effectively serving the behavioral health needs of children and families. Attention, however, must be paid to the potential for conflicts between the core educational mission of the school and the school becoming a de facto mental health service center (Blank et al., 1995). In the case of school-based mental health services, attention to academic retention and performance outcomes will be important to maintain productive partnerships in service of children and families.

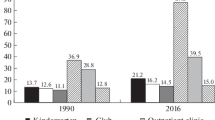

Although school-based mental health programs hold great promise for rural communities, adequate funding threatens their potential. A primary goal of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in the U.S. is to expand access to health services, including mental and behavioral health services. One vehicle for expansion of services has been funding of school-based health centers, many of which address and integrate mental and behavioral health services. A combination of federal, state, local, and private funding as well as attention to educational and cost-related outcomes will likely be necessary to develop and sustain locally developed and responsive school-based mental health programs (Cammack, Brandt, Slade, Lever, & Stephan, 2014).

Summary

Rural communities differ widely from one another, as do regions of any given country. Brown and Swanson (2003) quote Daryl Hobbs’ description of rural society: “When you’ve seen one rural community, you have seen one rural community.” There is, however, common impact of the substantial demographic changes that are occurring in rural regions.

Brown and Swanson (2003, p. 400ff) identify three related themes from the work of the authors in their sociological projective of rural American the twenty first century: “Community, civility, devolution,” the “importance of community,” and “locality-based policy” (pp. 400–401). They write, “Unlike earlier policy remedies, these trends do not carry with them exuberant promises of success. Rather, they represent throwbacks to traditional policy principles, even last ditch efforts, to address seemingly intractable development quandaries by institutionalizing framing principles of the America political economy: democracy, local initiative, civility and tolerance for our neighbors, recognition of the importance and obligations of private property, and the value of community. Institutionalizing foundation values will be more difficult if the current government and educational institutions serving rural America do not actively participate; however, it is difficult to imagine a better starting point for creating and realizing new policy opportunities for rural America” (p. 400).

It appears, then, that the hope of the development of meaningful mental health services in rural environments respects the three themes that Brown and Swanson discern in their work. Respecting the uniqueness of the cultures of local communities, the importance of community itself in the style of life chosen by rural residents and the importance of local control are central to creating and implementing effective services. Although the nature of interaction with state and federal governments consistently tests these principles, the local influence inherent in rural schools provides hope for preventive and responsive mental health services for vulnerable children and families.

References

Aggarwal, N. K., DeSilva, R., Nicasio, N. V., Boiler, N., & Lewis-Fernández, R. (2015). Does the cultural formulation interview (CFI) for the fifth revision of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) affect medical communication? A qualitative exploratory study from the New York site. Ethnicity and Health, 20, 1–28. doi:10.1080/13557858.2013.857762

Aisbett, D. L., Boyd, C. P., Francis, K. J., Newnham, K., & Newnham, K. (2007). Understanding barriers to mental health service utilization for adolescents in rural Australia. Rural and Remote Health, 7, 1–10.

Alarcón, R. D. (2009). Culture, cultural factors and psychiatric diagnoses. World Psychiatry, 8, 131–139.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5. Washington, DC: Author.

Annapolis Coalition on the Behavioral Health Workforce. (2004). An action plan for behavioral health workforce development: A framework for discussion. Washington, DC: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2016). Rural, remote and metropolitan areas classification. Retrieved from http://www.aihw.gov.au/rural-health-rrma-classification/.

Beale, C. L. (1996). Rural prisons: An update. Rural Development Perspectives, 11, 25–27. Retrieved from http://static.prisonpolicy.org/scans/rural_prisons_an_update_cl_beale.pdf.

Becker, A. E., & Kleinman, A. (2013). Mental health and the global agenda. New England Journal of Medicine, 369, 66–73. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1110827

Berg, M. T., & Lauritsen, J. L. (2015). Telling a similar story twice? NCVS/UCR convergence in serious violent crime rates in rural, suburban, and urban places (1973–2010). Journal of Quantitative Criminology. doi:10.1007/s10940-015-9254-9

Blane, D., Bartley, M., & Davey-Smith, G. (1997). Disease etiology and materialist explanations of socioeconomic mortality differentials. European Journal of Public Health, 7, 385–391.

Blank, M. B., Fox, J. C., Hargrove, D. S., & Turner, J. T. (1995). Critical issues in reforming rural mental health service delivery. Community Mental Health Journal, 31, 511–524.

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. (1997). The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children, 7, 55–71.

Brown, D. L., & Swanson, L. E. (Eds.). (2003). Challenges for rural American in the twenty-first century. College Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Cammack, N. L., Brandt, N. E., Slade, E., Lever, N. A., & Stephan, S. (2014). Funding expanded school mental health programs. In M. D. Weist et al. (Eds.), Handbook of school mental health: Research, training, practice, and policy. New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-7624-5_2

Department for Environment, Food, & Rural Affairs. (2012). Community safety partnership/local authority level from 2002/03′-Supplementary excel tables to ‘Crime Statistics, period ending March 2013. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/227013/Crime_Aug_2013.pdf.

Donzinger, S. (1996). The real war on crime. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Duncan, G. J., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Klebanov, P. K. (1994). Economic deprivation and early-childhood development. Child Development, 65, 296–318.

Emerson, E. (2007). Poverty and people with intellectual disabilities. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13, 107–113. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20144

Emerson, E., & Hatton, C. (2007). Contribution of socioeconomic position to health inequalities of British children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 112, 140–150. doi:10.1352/08958017(2007)112[140:COSPTH]2.0.CO:2

Evans, G. W., & Kim, P. (2007). Childhood poverty and health: Cumulative risk exposure and stress dysregulation. Psychological Science, 18, 953–957. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02008.x

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2012). Crime in the United States, 2012. Urban and Rural Crime. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Gibbs, R. (1998). College completion and return migration among rural youth. In R. M. Gibbs, P. L. Swaim, & R. Teixeira (Eds.), Rural education and training in the new economy: The myth of the rural skills gap (pp. 61–80). Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press.

Graham, S. E. (2009). Students in rural schools have limited access to advanced mathematics courses. Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire. Retrieved from http://www.carseyinstitute.unh.edu/publications/FS-Rural-married-couple-families-08.pdf.

Griffin, D., Hutchins, B. C., & Meece, J. L. (2011). Where do rural high school students go to find information about their futures? Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 172–181.

Gunderson, P., Donner, D., Nashold, R., Salkowicz, L., Sperry, S., & Wittman, B. (1993). The epidemiology of suicide among farm residents or workers in five north-central states, 1980–1988. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 9, 26–32.

Hooks, G., Moser, C., Rotolo, T., & Lobao, L. (2004). The prison industry: Carceral expansion and employment in US counties 1969–1994. Social Science Quarterly, 85, 37–57.

Huling, T. L. (2002). Building a prison economy in rural America. In M. Mauer & M. Chesney-Lind (Eds.), From invisible punishment: The collateral consequences of mass imprisonment (pp. 197–213). New York, NY: The New Press.

Johnson, K. (2006). Demographic trends in rural and small town America. Carsey Institute Reports on Rural America, 1, 1–33. Retrieved from www.carseyinstitute.nh.edu/documents/Demographics_complete_file.pdf.

Johnson, K. (2012). Rural demographic change in the new century: Slower growth, increased diversity. Carsey Institute Reports on Rural America, 22, 1–12. Retrived from scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1158&context=carsey.

Kleinman, A. (1988). The illness narratives: Suffering, healing, and the human condition. New York: Basic Books.

Lapan, R. T., Tucker, B., Kim, S., & Kosciulek, J. F. (2003). Preparing rural adolescents for post-high school transitions. Journal of Counseling & Development, 81, 329–342.

Lawlor, D. A., Ronalds, G., Macintyre, S., Clark, H., & Leon, D. A. (2006). Family socioeconomic position at birth and future cardiovascular disease risk: Findings from the Aberdeen children of the 1950s cohort study. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1271–1277.

Mohatt, D. F., Bradley, M. M., Adams, S. J., & Morris, C. D. (2005). Mental health and rural America, 1994–2005. Rockfille, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Monk, D. H. (2007). Recruiting and retaining high-quality teachers in rural areas. The Future of Children, 17, 155–174. doi:10.1353/foc.2007.0009

Moore, K. A., Redd, Z., Burkhauser, M., Mbwana, K., & Collins, A. (2009, April). Children in poverty: Trends, consequences, and policy options (CT Research Brief No. 11). Retrieved from http://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/2009-11ChildreninPoverty.pdf.

Mullins, L. L., & Chaney, J. M. (2013). Introduction to the special issue: The impact of poverty and rural status on youth with chronic health conditions. Children’s Health Care, 42, 191–193. doi:10.1080/02739615.2013.816593

National Center for Education Statistics. (2013). Navigating resources for rural schools. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

National Institute of Justice. (2004). Law enforcement technology—are small and rural agencies equipped and trained? Research for Practice. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

National Institute of Justice. (2010). Report on the National Small and Rural Agency Summit. August. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

National Resources Defense Council. (n.d.). Unchecked fracking threatens health, water supplies. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.nrdc.org/energy/gasdrilling/.

New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. (2003). Achieving the promise: Transforming mental health care in America, final report (DHHS Publication No. SMA-03-3832). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Olgun, A., Gumus, S. G., & Adanacioglu, H. (2010). Schooling and factors affecting decisions on schooling by household members in the rural areas of Turkey. Social Indicators Research, 98, 533–543. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9564-0

Owens, J. S., Watabe, Y., & Michael, K. D. (2013). Culturally responsive school mental health in rural communities. In C. S. Clauss-Ehlers et al. (Eds.), Handbook of culturally responsive school mental health: Advancing research, training, practice, and policy. New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4948-5_3

Provasnik, S., Kewal Ramani, A., Coleman, M., Gilbertson, L., Herring, W., & Xie, Q. (2007). Status of education in rural America (NCES 2007–040). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Roscigno, J. V., Tomaskovic-Devey, D., & Crowley, L. M. (2006). Education and the inequalities of place. Social Forces, 84, 2121–2145.

Roscigno, V. J., & Crowley, M. L. (2001). Rurality, institutional disadvantage, and achievement/attainment. Rural Sociology, 66, 268–293. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2001.tb00067.x

Sangaramoorthy, T., Jamison, A. M., Boyle, M. D., Payne-Sturges, D. C., Sapkota, A., Milton, D. K., & Wilson, S. M. (2016). Place-based perceptions of the impacts of fracking along the Marcellus Shale. Social Science & Medicine, 151, 27–37. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.002

Timaeus, I. M., & Moultrie, T. A. (2015). Teenage childbearing and educational attainment in South Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 46, 143–160. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2015.00021.x

U.S. Census Bureau. (2015, July). Urban and rural classification. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/urban-rural.html.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2014, November). Rural American at a Glance: 2014 edition. Economic Brief, 26.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2015, December). Child poverty. Retrieved from http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being/child-poverty.aspx.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Federal Office of Rural Health Policy. (2015). Defining rural population. Retrieved from http://www.hrsa.gov/ruralhealth/aboutus/definition.html.

U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2011). Crime in the United States, 2010. Uniform Crime Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Vernon-Feagans, L., Burchinal, M., & Mokrova, I. (2015). Diverging destinies in rural America. In P. R. Amato et al. (Eds.), Families in an era of increasing inequality, National Symposium on Family Issues (vol. 5, pp. 35–49). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08308-7_3

Walker, J. L., & Walker, L. J. S. (1988). Self-reported stress symptoms in farmers. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 10–16.

Weisheit, R. A., Falcone, D. N., & Well, L. E. (1994, September). Rural crime and rural policing. National Institute of Justice: Research in Action, 1–15.

Yoshikawa, H., Aber, J. L., & Beardslee, W. R. (2012). The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: Implications for prevention. American Psychologist, 67, 272–282. doi:10.1037/a0028015

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hargrove, D.S., Curtin, L., Kirschner, B. (2017). Ruralism and Regionalism: Myths and Misgivings Regarding the Homogeneity of Rural Populations. In: Michael, K., Jameson, J. (eds) Handbook of Rural School Mental Health. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64735-7_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64735-7_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-64733-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-64735-7

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)