Abstract

The chapter takes as its starting point three potential approaches to religious education (namely instruction, formation and education) discussed in an influential report on English schools. It is noted that the notion of religious formation has been a problematic idea for many teachers since the 1970s. The current discomfort is traced through intensive case study research with 14 teachers in church secondary schools. The chapter then develops the notions of formation and instruction, arguing that the concept of instruction is based on a positivist understanding of Christian learning whereas the concept of formation is better understood through a hermeneutical model of learning. Interpreted as such, formation offers a productive model for Christian Education.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Clarke and Woodhead

- Formation

- Instruction

- Education

- Hirst

- Christian ethos

- Positivism

- Responsible hermeneutics

- Epistemic humility

Introduction

The language of formation is not much used in discussions of education in England, except within Catholic schools . That is probably because it raises the spectre of indoctrination , which is still one of the cardinal sins for a teacher . To admit to engaging in formation as a Christian teacher would be likely to attract the charge of confessionalism , which is widely regarded as professionally illegitimate (e.g. Alberts 2007). Many years ago, the influential philosopher of education Professor Paul Hirst (1974, 1981) described Christian formation as ‘primitive’ in contrast to the ‘sophisticated’ approach to education based on rational principles alone that he advocated. Although few today would recognise Hirst’s name, many teachers live under the panoptic jurisdiction of his distinction. They experience the influential gut-feeling that education ought to be based on a neutral consensus that is common to all human beings on account of their shared rationality and values . It is this, they feel, that should be engaged in by teachers in state-funded schools and not formation based on the controversial and ideological beliefs of religious or other particularistic belief communities . Education, it is assumed, should be a neutral, secular space where people of different beliefs participate together in consensus-based learning , not a tribal, sectarian space where controversial beliefs are normative in a process of religious formation.Footnote 1

However, in an influential position paper Charles Clarke, a former Labour Secretary of State for Education, and Professor Linda Woodhead, a sociologist of religion at Lancaster University, ( Clarke and Woodhead 2015) broke rank and used the term ‘formation’ as a way of trying to cut through the Gordian knot that bedevils discussions of the nature and purpose of religious education in schools. Their goal appeared to be to find a way of embracing the aspiration of the increasing number of faith school providersFootnote 2 to offer an education shaped by a religious ethos , but without condoning a form of religious influence that would be illegitimate in the state-funded schools of a plural democracy like England. The threat posed by religious radicalisation and the need for schools to combat that was, no doubt, never far from their minds in their grappling with this issue.

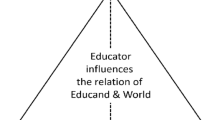

In discussing the purpose of religious education, Clarke and Woodhead identified three possible models: instruction, formation and education (2015, pp.32–35). They suggested that instruction disavows both critical questioning and the consideration of alternative views and is, therefore, what the critics would describe as indoctrination . It is not, they asserted, an appropriate activity for schools. However, in their view it is an appropriate religious activity outside schools since ‘trying to embed young people within a particular religious or non-religious tradition ’ is legitimate in a ‘society which upholds freedom of religion or belief’ (p.33).

Formation, they argued, may have similar goals to instruction in that it entails some form of induction into a religious way of life, but, most importantly, contrasts with it (a) by giving ‘room for agency , questioning and criticism by pupils ’ and (b) because it ‘does not ignore distort or caricature other forms of religion or belief’ (p. 34). This legitimates it as an appropriate activity for state-funded schools. They did, however, think it was important that schools made clear to prospective parents the nature of the formation offered with some precision (e.g. not just Christian but evangelical Christian). This clearly means they expect the school leadership to give detailed consideration to the nature of the ethos . Significantly, Clarke and Woodhead go further and suggest that all schools, not just schools with a religious character, should be required to articulate the nature of the formation that they offer saying; ‘it would also be desirable if non-faith (sic) schools were equally clear and self-conscious about the sort of formation they offer (e.g. liberal humanist, secular egalitarian etc.)’ (p.34). This statement implies recognition that all schools are inescapably involved in formation and is important because, if correct, it means that no school is neutral since all are involved in distinctive formation of some kind. The challenges of managing distinctiveness of ethos are not, therefore, unique to schools with a religious character, a point often argued by religious commentators but not before, in my experience, quite so explicitly acknowledged by secular discussants.

Clarke and Woodhead’s third model is education, which they describe as being ‘critical, outward looking and dialogical’ and an approach which ‘recognises diversity’. It is envisaged as preparing young people for life ‘in a multi-faith society and a diverse but connected world’ (p.34). This is their preferred approach, which they believe enjoys ‘understanding and support’ in the population at large and should take place in all schools. Unfortunately, this proposal leaves the Gordian knot uncut because it is a return to the binary choice between sophisticated secular education and primitive religious formation (albeit less primitive than instruction). Furthermore, the distinction between formation and education collapses in the one sentence mentioned above where Clarke and Woodhead acknowledge (apparently) that all schools (be they religious or not) are inevitably formational institutions. If this is true, it does not then make any sense to propose a third model called education, which seems to imply that a non-formational approach that escapes the requirement to be clear about its ethos is a possibility.

The Clarke/Woodhead overall conclusion appears to be that, in state-funded schools, religious instruction should be prohibited, religious formation could be tolerated, although perhaps reluctantly as a price of religious freedom , but religious education should be encouraged or perhaps even required. In other words, it is the ideal. In the end, it seems that Clarke and Woodhead have embraced the primitive/sophisticated divide that still regards formation as problematic in contrast to education, although, for political reasons, they feel that formation has to be permitted. In this chapter, I will offer a more enthusiastic embracing of their concept of formation.

The key distinction, if any is to be made, is, I suggest, between instruction and educational formation, with the former being inappropriate and the latter being what all schools, be they religious or not, should offer. I will also argue that formation, and not instruction , should be the desired goal for religious nurturing activity outside of education. What then distinguishes instruction and educational formation is, following Clarke and Woodhead, first that pupil agency , questioning and criticism is encouraged, second that other belief positions are not ignored, distorted or caricatured, and third that pupils are equipped for contributing positively as citizens to a society where diversity of religion and belief prevails. In this chapter, I will explore an approach to Christian educational formation that shares these aspirations. However, I shall not restrict my comments purely to the classroom subject of religious education , as Clarke and Woodhead do, but will address learning across the whole curriculum and the role of Christian formation in that.

In contrast with the Clarke and Woodhead approach,

-

(1)

I will challenge the apparent assumption that somehow religious activity is necessarily in conflict with the responsibility of state-funded education to promote pupil agency, openness to diversity and the common good;

-

(2)

I will give up the notion that there is a sophisticated, consensus or neutral position derived from shared human values and rationality that can transcend the differences that exist between the different religious and non-religious communities present in modern Britain and is the desired or even required approach for state-funded education;

-

(3)

I will offer an epistemological diagnosis of the challenge and outline an alternative prescription that might offer a solution.

Formation as Perceived in Christian Education in England

In my introduction, I suggested that teachers in England operated under the panoptic jurisdiction of the primitive/sophisticated binary. I will now illustrate this from a research project which I led that involved a year’s in-depth work with 14 secondary school teachers representing a range of subject expertise from three church schools in England.Footnote 3 The research was designed to explore how the teachers interpreted the challenge to teach in a way that promoted Christian character formation through their everyday classroom work.Footnote 4 The researchers worked with the teachers for an academic year, observing them teach, holding focus group discussions with their students, reading the logs that the teachers kept and interviewing them on several occasions. The result was 14 rich case studies of teachers’ joys and struggles in their classrooms (Cooling et al. 2016). In the research, we observed many fine examples of what we judged to be teachers reshaping their classroom approach in creative and successful ways in response to the challenge. However, we also unearthed a fundamental issue (Cooling et al. 2016, pp.87–97).

The issue was encapsulated by Dawn, a maths teacher who described what she was being asked to do in the project as ‘weird’, using the word to introduce a lesson to her class that she had designed to fulfil what she understood to be the aim of the project, whilst also commenting to them that what they were about to do was ‘not proper maths’. Further on in the lesson, she told the students that she preferred ‘just teaching you maths’. She displayed a palpable sense of discomfort at the idea of introducing Christian ethos into mathematics. In her final interview, she described her experience as ‘shoe-horning’ and ‘strong-arming’ God into the mathematics lesson in a way that is ‘not natural’, violating what she regarded as her core professional responsibility, namely teaching mathematics. Fitting Christian ethos ‘with something as abstract as linear equations’ did not seem possible or justifiable to Dawn.

This reaction was nothing to do with antipathy on her part to the idea of Christian ethos permeating school life as Dawn was the senior teacher responsible for this aspect in her school. Indeed, she was very positive about the Christian pastoral and liturgical life of the school and advocated, for example, that all lessons should begin or end with prayer. Her hesitations were, it appeared, down to a sense that the integrity of mathematics was being violated by seeking to teach it as part of a programme of Christian formation.

This sense of weirdness was also expressed by Charlotte, a geography teacher . In her case this did not appear to derive from concern about violating the integrity of her subject; rather for her there was an issue of professional pedagogical integrity. The heart of the matter seemed to be that normally she would lead what she described as ‘completely open conversation that takes whatever course it takes’ but in being asked to teach in a distinctively Christian way she felt constrained by an obligation ‘to direct the conversation’ and felt uncomfortable that she was to her mind ‘pushing Christian values ’. Apparently lurking beneath her discomfort was a sense that she was required to indoctrinate Christian values in a search for conformity rather than teaching to promote autonomy , which she regarded as her professional commitment.

Another dimension to this sense of weirdness relates to the perception that some of the teachers appeared to believe that Christian formation requires telling students Christian truths in all subjects of the curriculum. This felt over the top for most of our teachers ; almost too Christian amounting to, so to speak, levering in a Christian sermonette on sin and salvation between algebra and trigonometry. On the other hand, we also unearthed a concern in the teachers’ minds that their teaching might not actually be ‘Christian enough’. As physics teacher Paul pondered, ‘How explicitly Christian does the lesson have to be to qualify as not tokenistic?’ adding that ‘… there’s a sense in which anything that doesn’t see people becoming Christians isn’t fulfilling the ultimate mission’. Not to do this is ‘wishy-washy’.

My conclusion from studying the research data was that a significant reason for these teachers ’ difficulties with being asked to engage in Christian formation was that they assumed that Christian faith ought to be dealt with in an instructional mode for the lessons to be properly Christian. By this, I mean that the teachers perceived the required process to be all about telling Christian truths to pupils with a view to persuading those pupils to accept the truths . Anything less was, to quote Paul, ‘tokenistic’ and ‘wishy-washy’. However, the teachers were deeply uncomfortable about operating within this instructional paradigm, because they regarded it as poor teaching and unethical to behave in this way in a classroom. It neither honoured the significance and integrity of their subject nor did it respect the pupils ’ rights to freedom of belief or recognise the diversity of viewpoints amongst the pupils , their families and in the wider world. They therefore identified strongly with the Clarke/Woodhead concerns about instruction . But for some reason they felt they were being disloyal to the Christian faith if they did not put an emphasis on the instructional goal of persuading pupils to accept Christian truths . They seemed to feel that they had to attempt to control the development of the pupils ’ thinking in an inappropriate way if they were going to honour the school’s aspiration to engage in Christian formation in their classrooms.

The Assumption of Positivism

Unfortunately, our research did not go as far as to investigate why the teachers apparently assumed that instruction was the required model when ‘embedding’ pupils within a religious ethos. However, Clark and Woodhead seem to share this assumption saying that ‘Religious instruction should be principally the responsibility of religious communities and families’ ( Clarke and Woodhead 2015, p.33). Is the implication of this statement that religious formation, with its emphasis on pupil agency and acknowledgement of diversity, is not then something that religious communities would be expected to embrace? Is there something in common here with our teachers —namely the implicit expectation that loyal Christian teachers will adopt an instructional approach? Is there a suggestion here that embracing a formational approach entails a degree of compromise of the Christian faith ? As Paul the physics teacher asked in his log, is anything less than the attempt to persuade pupils to accept the truth of Christian beliefs perceived as tokenistic, wishy-washy and not fulfilling the ultimate Christian mission? It appears that some of our teachers may have held these implicit assumptions.

This first emerged as an issue for me when I was studying for my PhD (Cooling 1994). As an undergraduate, I was inspired by the writings of Francis Schaeffer, an immensely influential Christian apologist who, in the second half of the twentieth century, challenged the modernist assault on biblical Christianity. He was one of the pioneers of the now influential movement that stresses the importance of Christian scholarship. I owe a great personal debt to his work. However, in returning to his writing as a doctoral student of Christian education a decade later, I was troubled by his approach to learning . The task for Christian educators seemed to be, metaphorically, to get the non-believer with their back against the wall so they had no option but to convert or despair. He called this ‘loving confrontation’. Diversity was not to be acknowledged; pupil agency seemed to be little valued. Learning was achieved when students were persuaded to accept Christian truth . Different interpretations were to be resisted, not accommodated. To learn well was to accept true doctrine.

A recent letter published in IDEA, the bi-monthly magazine of the English Evangelical Alliance, provides a clue to the origins of this approach. The correspondent wrote:

If God is as revealed in the Bible and the Bible is the Word of God, then the Bible is by implication inerrant. God is the God of truth and cannot lie, so He is not going to give us as His revealed word something that is untrue. (Campbell 2016)

The assumption behind this assertion appears to be that the correspondent’s interpretation of what any passage in the Bible means can be assumed to be exactly what God intended; indeed, that it is not an interpretation because the Bible always has a plain meaning. In other words, the Bible gives us direct access to God’s intentions.

What I suggest is manifested here is what I shall call a positivist approach to Christian faith . Positivism is not, to my mind, a belief system like atheism or Judaism. Rather it is a mindset, a way of holding beliefs that can be manifested by atheists and religious believers alike. It is a particular approach that people take to the knowledge that they believe they have gained in their life. Positivism is usually associated with a scientific approach to knowledge. This values the concept of objectivity and aspires to the notion that true knowledge applies universally irrespective of the vagaries of belief. The role of education then is to pass on the uncontroversial knowledge that is the accumulation of objective academic enquiry over time. Evidence and argument lead decisively to truth . Positivism assumes that education can confidently induct pupils into the universal, established truths that are the reliable products of rational thought and its methods. It assumes consensus. Paul Hirst is an influential exemplar of the approach.

Given this description, it does not seem to make much sense to suggest that there is a Christian version of positivism. But that is exactly my hypothesis. I suggest it shares scientific positivism’s confidence in inducting others into secured truths and its unwillingness to engage with alternative viewpoints. In his concern to challenge the seeming assault by scientific positivism, Schaeffer adopted the positivist paradigm in relation to his Christian faith . As God’s infallible revelation , the Bible is the source of assured, true knowledge ( Schaeffer 1968). Non-believers can be persuaded of its truth and believers are obliged to seek to so persuade them. The way to combat scientific positivism is, it is often assumed, with Christian positivism.

In their discussion of attitudes to the Bible and their impact on approaches to teaching and learning , Christopher Rowlands and Jonathan Roberts (2008) capture the implications of this model in their description of teaching and learning as ‘baton exchange ’. This consists of the expert biblical exegete discerning the fixed meanings of the text , the theologian systematising them and then the preacher and teacher applying them to life situations in modern contexts with the learner absorbing the resulting sound teaching as the final step in a linear, transmission model of learning (pp.35–36). Here learning is perceived as top-down transmission resulting, when successful, in the acceptance of authorised, authoritative meanings by the learner.

My hypothesis is that the effect of this positivist paradigm is to push people towards assuming that apologetics , the theological discipline of arguing for the faith with the intention of persuading others, is the main purpose of Christian education. The nature of apologetics is summarised in this quotation, where a leading centre in the discipline describes its function as follows:

The Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics exists to equip Christians to defend the Christian faith against such attack, on both a popular and an academic level, offering a counter-claim to modern-day secularism . (Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics 2017)

I am not seeking to dismiss apologetics as a legitimate Christian academic discipline; far from it. It is an extremely important discipline for theological defence in the public square. Rather I wish to make two suggestions in relation to discussions of education. First, that apologetics , when combined with an acceptance of a positivist paradigm as the appropriate response to secular positivism, easily leads to the assumption that Christian education should follow an instructional model. Second, that the evidence we have from our research suggests that teachers feel that to be a faithful Christian teacher , one’s approach to education should be that of the positivist apologist. Anything less is perceived as disloyal as it lacks confidence in the assured truths that come from God’s word. Although our teachers did not explicitly articulate this positivist, apologetic approach, they did seem to assume that the instructional pedagogy that follows from it was required in a genuinely Christian approach to formation. It also seems that Clarke and Woodhead may have shared this assumption. However, our teachers found this pedagogical model to be weird and were uncomfortable with what they thought they were being asked to do in their Christian ethos schools. Clarke and Woodhead too epitomised the widespread unease with this instructional model.

An Alternative to Positivism

However, this assumption that to be faithfully Christian in education one has to adopt a positivist paradigm alongside apologetics as the framing theological discipline is simply not true. There are many scholars who share Schaeffer’s conservative commitment to the Bible as the source of God’s truth, but who do not take this positivist line to learning .Footnote 5 Loosely they can be described as interpretivist in orientation, meaning that one of the key features of their work is that they recognise that living under the authority of the Bible inescapably entails the fallible activity of human interpretation . For them, God certainly speaks through scripture , but they acknowledge that often humans do not listen so well. The appropriate response is then, according to interpretivists, not to treat my interpretations as being of the same status as God’s word, as tends to happen if people are operating under the influence of a positivist paradigm.

Anthony Thiselton (2009) is one among many influential scholars in the field of biblical interpretation . His concept of responsible hermeneutics, I suggest, offers a way forward. Thiselton maintains that the distinction between what he calls exegesis and hermeneutics is that in hermeneutics one asks ‘exactly what are we doing when we read, understand and apply texts ?’ (p.4) whereas there is a tendency to assume that exegesis is a science that enables one to unearth the objective meaning of a text . Exegesis reflects, then, a positivist mindset. In contrast, he argues that every reader approaches the text with a ‘pre-understanding’, which he describes as ‘an initial and provisional stage in the journey towards understanding something more fully’ (p.12). No one, then, reads a text in the positivist way. There is always a subjective process of constructing meaning, which draws on one’s worldview , reflects one’s cultural situatedness and often serves one’s own interests. The existence of pre-understanding is simply a fact of life, namely that we all interpret from somewhere; he argues that this is not inherently threatening to the enterprise of discovering truth, but, importantly for our topic, it does have to be taken into account. Responsible hermeneutics is then the activity of seeking meaning in biblical texts that lead to greater understanding of God’s truth , whilst taking account of the fallibility of the human interpreter in doing this.

The implication of using responsible hermeneutics as a model of learning can be appreciated through New Testament theologian N. T. Wright’s widely cited analogy where he compares living under the authority of the biblical text with the task of completing a newly discovered but unfinished Shakespeare play ( Wright 1992, pp.139–143).Footnote 6 Wright asks us to imagine how experienced Shakespearean actors would go about this task. He suggests two significant insights. First, they would seek to be faithful to the thrust of the narrative of the unfinished play and to Shakespeare’s wider corpus of writing, which acts as an authority. Their suggested completion of the play must be ‘justifiably Shakespearean’, a concept, which acts as a constraint on the actors’ creativity and honours the authority of the originating author. Second, they would need to be creative in writing the new text and this creativity would inevitably reflect their own situated, contextual setting and personal interests. Wright argues that Christians seeking to live their lives under the authority of Scripture face a similar task to these Shakespearean actors. The analogy affirms the conservative acceptance of the Bible as authoritative and truth-revealing, but without embracing the positivist mindset by recognising the human creativity entailed in interpreting and living under the authority of a text or tradition . It provides an invigorating metaphor of Christian formation.

This change in perspective from positivist apologetics to interpretivist hermeneutics has huge implications for how we conceive of Christian formation. Firstly, it affirms pupil agency since hermeneutics recognises the important role of learners and their context in constructing the meaning of the texts . Secondly, it demands recognition of diversity because the role of pre-understanding means that diversity of interpretation rather than consensus is to be expected. A number of commentators (e.g. Briggs 2010; Vanhoozer 1998) therefore argue that epistemic humility becomes a key virtue for successful hermeneutics , given the recognition of the influence of pre-understanding on our interpretive conclusions. In turn, this leads to a more hospitable response to the ideas of others (Bretherton 2010). Instead then of the oppositional, proclaiming, response to difference that follows from positivist apologetics , interpretivist hermeneutics motivates a listening, curious, critical and enquiring response. Christian formation in schools then that is modelled on interpretivist hermeneutics will not result in the baton passing, instructional models that do not honour pupil agency and are overly defensive in the face of difference and which Clarke and Woodhead argue are not appropriate in state-funded schools. Furthermore, if Thiselton, N. T. Wright and other hermeneutical scholars are correct, neither is such an instructional approach an appropriate religious activity, be that in home or church. Rather the Clarke/Woodhead formative approach seems to be the model for both school and faith community contexts. If that is true, it makes no sense to create the tripartite distinction between instruction, formation and education. Rather it should be recognised that there is a choice only between instruction, based on a positivist paradigm, and formation, based on an interpretivist paradigm. The latter, I suggest, is what both schools and faith communities should seek after, in ways that are appropriate in each of their contexts. The aim should be to produce wise interpreters. We should, however, abandon the notion that something called education, which has no formative agenda, is attainable

The outcomes of this shift in paradigm can be briefly illustrated from the story of one of the teachers in the research project. Angela taught GCSE Religious Education (Cooling et al. 2016, pp.77–80).Footnote 7 One of the modules was on social issues around the end of life. In the research, she focused on teaching a topic on assisted suicide. The usual question format in the exam is for students to be asked to give three arguments for and three against assisted suicide. Angela’s past practice had been to teach her students to construct these arguments with the assumption that the Christian view was against assisted suicide and that a secular view was supportive of it. The three Christian arguments were supported by biblical texts.

In the course of the project, Angela started to reflect on the perception that her students were gaining of Christian ethics through this approach. She didn’t like the conclusion she came to, namely that Christian ethics is primarily concerned with winning arguments by ‘machine-gunning’ one’s opponents with Bible proof texts . This approach seemed to induct pupils into positivist oppositionalism. Inspired by the work of theologian Luke Bretherton (2010) on the biblical portrayal of ethical differences, she decided to take an entirely different pedagogical approach. She took Bretherton’s key argument that the Bible’s primary response to ethical dispute was to seek to offer Christian hospitality to one’s opponent and asked how this biblical insight might shape the way she taught this contentious topic. Instead of having students develop ‘three arguments for, three arguments against’, she sought out video material from individuals who had first-hand experience of these very challenging decisions and set students the task of explaining each of their points of view. The rule was ‘listen before you argue’. In that way, she hoped that students would take away the idea that Christian ethics is not primarily about winning arguments by quoting biblical proof texts, but is rather about showing hospitality to those we dispute with by employing interpretive hermeneutics in an attempt to reach a God-honouring conclusion. Only then did she allow them to undertake the ‘three arguments for, three arguments against’ exercise required by the exam.

Angela’s change of heart on her pedagogy exemplifies a shift from learning framed by positivist, apologetic Christianity to learning framed by interpretivist, hermeneutical Christianity. Both approaches seek to teach in a way that honours the authority of the Bible in the Christian life. However, the positivist way uses it as a source of ‘true-truths ammunition’ for proving others wrong with the intention that the students should agree with the presumed Christian line. In contrast, the interpretivist approach recognises the different ways in which scriptural teaching can be interpreted on a contentious issue and prioritises a biblical approach to how we behave in the midst of ethical disputes. Above all, the interpretivist pedagogy does not seek to control the students’ conclusions, whilst still acknowledging that the Bible is an authoritative source of God’s truth. However, it does frame their learning experience within a biblical approach as to what it means to learn well in Christian ethics. This transition enabled Angela to honour the diversity of viewpoints in the wider world and changed the focus of her lesson from persuading students to accept Christian truths to enabling students to think for themselves in using the Bible . Furthermore, it offered her a way of being distinctively Christian in her teaching through reframing her pedagogy rather than, to use Dawn’s phrase, through levering in Christian content. Her reflection on what had happened was that it had been painful because it ‘made me question what I’m teaching and why I’m teaching’, but that the experience meant that she had ‘just changed my whole mind-set on everything I do’.

The case study of Angela’s experience illustrates three characteristics of the impact on pedagogy of a change of paradigm from positivist apologetics to interpretivist hermeneutics where the role of pre-understanding as the starting point for the interpretive process that leads to the development of knowledge is embraced:

-

(1)

Bringing this into conscious reflection enabled Angela to reflect on how the GCSE course structure resulted in her framing her teaching in a way that led students to imagine that Christian ethics was primarily about winning arguments and to reframe that so that they no longer thought that, in an ethical dispute, being Christian was primarily about being right but rather about loving your opponent.

-

(2)

An emphasis on critical questioning and students working out the significance of ideas for themselves, replaced the previous emphasis on pupils repeating pre-rehearsed stereotypical responses to complex questions.

-

(3)

The importance of hearing other voices became central to the personal and academic development that was the desired outcome.

Conclusion

In embracing the notion of formation, Clarke and Woodhead took a significant and welcome step towards moving beyond the influential binary thinking that distinguishes sophisticated, secular education from primitive, religiously confessional education. In this chapter, I have built on their idea by arguing that all education should be thought of as formative. The key distinction then is between instructional approaches that are built on positivist apologetic paradigms and formational approaches that are built on interpretivist hermeneutical paradigms. The latter facilitate pupil agency, wise interpretation and helpful responses to diversity. As Woodhead and Clarke point out, such an approach applies in all educational contexts, including non-religious community schools (and not just to schools with a religious character) and the religious activities of home and church that seek to embed young people within a religious ethos .

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Linda Woodhead and Charles Clarke for their comments on a draft of this chapter and for their gracious interaction with my critique of their paper. I again wish to acknowledge the stimulus their ideas have been in my thinking and to declare my appreciation of their opening up the debate on formation. I recognise that they do not agree with all my conclusions.

Notes

- 1.

I do not intend to address the issue of neutrality in detail here, but only wish to note its widespread influence. For a detailed discussion, see Cooling (2010).

- 2.

This is the popular term for schools and academies that are sponsored by religious communities , but is often rejected by them as, for example, by the Church of England . The reason for this rejection is that faith schools are often assumed to be solely for members of that religious community , whereas the majority actually recruit students from a range of religious and non-religious backgrounds. The technically correct, although cumbersome, term is schools of a religious character.

- 3.

Church schools in England are state-funded schools founded by Christian churches. The schools we studied were either Church of England or Catholic.

- 4.

It utilised an approach called What If Learning. See www.whatiflearning.co.uk.

- 5.

Examples of writers who have helped me greatly are Alister McGrath, Anthony Thiselton, Kevin Vanhoozer, Tom Wright and Christopher Wright.

- 6.

Note my description here is truncated and thereby misses many of the nuances of Wright’s original and the subsequent discussion of it. In Wright’s approach, the authority of the text does not then primarily reside in individual propositions, but in the overall narrative or storyline.

- 7.

GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education) is the 16+ public examination in England.

References

Alberts, W. (2007). Integrative Religious Education in Europe. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Bretherton, L. (2010). Hospitality as Holiness: Christian Witness Amid Moral Diversity. London: Routledge.

Briggs, R. S. (2010). The Virtuous Reader: Old Testament Narrative and Interpretive Virtue. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

Campbell, N. (2016, July/August). Biblical Inerrancy – Continued. IDEA Magazine, 33.

Clarke, C., & Woodhead, L. (2015). A New Settlement: Religion and Belief in Schools. Lancaster: Westminster Faith Debates.

Cooling, T. (1994). A Christian Vision for State Education. London: SPCK.

Cooling, T. (2010). Doing God in Education. London: Theos.

Cooling, T. with Green, B., Morris, A., & Revell, L. (2016). Christian Faith in English Church Schools: Research Conversations with Classroom Teachers. Bern: Peter Lang.

Hirst, P. H. (1974). Moral Education in a Secular Society. London: University of London Press.

Hirst, P. H. (1981). Education, Catechesis and the Church School. British Journal of Religious Education, 3(3), 85–93.

Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics. (2017). What Is Apologetics? [online]. Retrieved March 25, 2017, from https://www.theocca.org/what-is-apologetics

Rowlands, C., & Roberts, J. (2008). The Bible for Sinners. London: SPCK.

Schaeffer, F. (1968). Escape from Reason. Leicester: InterVarsity Press.

Thiselton, A. (2009). Hermeneutics: An Introduction. London: SPCK.

Vanhoozer, K. (1998). Is There a Meaning in This Text? The Bible, the Reader and the Morality of Literary Knowledge. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Wright, N. T. (1992). The New Testament and the People of God. London: SPCK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Cooling, T. (2018). Formation and Christian Education in England. In: Stuart-Buttle, R., Shortt, J. (eds) Christian Faith, Formation and Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62803-5_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62803-5_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-62802-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-62803-5

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)