Abstract

Customer engagement (CE) reflects the increased ease with which business-to-consumers (B2C) customers can engage with firms and other customers outside of face-to-face interactions. However, increased customer engagement brings with it uncertainty regarding the future of B2C salespeople. Traditionally, salespeople have been a firm’s primary method of engaging customers, but with customers now entering sales interactions highly engaged, the question is, are B2C salespeople still needed? To explore this timely issue, a focus group is employed and themes are developed, which interestingly run counter to suggestions in the literature that salespeople should act as “knowledge brokers” to create value with their customers. In fact, the findings indicate that face-to-face interaction may actually impede, rather than create, value. The chapter concludes by presenting theory-based solutions to this problem.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Customer engagement (CE) is an increasingly studied topic in marketing that relates to the attitudes, behaviors, and connectedness of customers to a firm and to the firm’s other customers (i.e., the marketplace; see Kumar et al. 2010; Kumar and Pansari 2016; Van Doorn et al. 2010). CE has become an important topic because it reflects the increased ease with which business-to-consumer (B2C) customers (largely empowered by new technology) can engage with firms and other customers outside of face-to-face interactions. Overall, this is seen as a positive change—firms want better access to, and deeper relationships with, customers, and technology-driven CE facilitates this (Kumar and Pansari 2016). However, this development brings with it uncertainty regarding the future of B2C salespeople and the organizations that employ them because, traditionally, the sales force has been a firm’s primary method of engaging customers. Research by Beatty and Smith (1987), for example, showed that in the past the bulk of a customer’s external information search came from in-person sales interactions. However, more recent work suggests that this is no longer the case, as customers now enter sales interactions much later (57–70% of the way through decision) and after considerable prior engagement (Microsoft 2015). With customers now entering sales interactions highly engaged and informed, the question is, where does this leave the B2C salesperson?

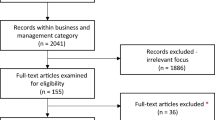

While research is limited on this issue, industry reports have predicted that firms’ newfound focus on CE outside of sales interactions is contributing to the demise of direct selling. For example, a report by Forrester Research suggests that one million, mostly order taker, sales jobs will be lost by 2020 (Hoar 2015). This decline is predicted because customers can now self-educate and make decisions separate from the sales interaction, which is precipitating a move of their purchasing activities to e-commerce sources. This point is further emphasized by a McKinsey report that reveals that car shoppers today visit only 1.6 dealerships before making a purchase decision (compared to 5 dealerships just a few years ago; Economist 2015). Figure 9.1 visually represents changes to how customers engage, within and external to sales interactions. The issue addressed by this chapter, how CE outside the direct sales interaction impacts CE inside the interaction, is important for reasons far beyond academic interest. If these doomsday prophets are correct, success in encouraging CE external to the sales interaction is ushering in the end of direct selling. While this may be a goal for some firms, we contend that diminishing direct CE also portends a decrease in the quality consumer decisions (i.e., decreased value) that has traditionally been a benefit of in-person sales interactions.

In order to explore this important and timely issue, we held a focus group with executives in the retail jewelry industry on the topic of the challenges involved in selling to engaged customers. The themes developed from this focus group run counter to suggestions in the literature that salespeople who act as “knowledge brokers ” will be successful in creating value with their customers. In fact, the findings indicate that for customers highly engaged outside the sales interaction, a salesperson’s efforts to engage within the face-to-face interaction may actually impede, rather than create, value. Thus, in the remainder of this chapter, we start by reporting the key themes that emerged from our focus group study. Concurrently, we introduce literature related to each theme and then propose a conceptual, literature-based solution to these key challenges by drawing upon research on CE, personal selling, and psychology. A summary of the main literature referenced is detailed in Table 9.1.

Focus Group and Literature Review: Key Challenges in Selling to Engaged Customers

To begin our investigation of how CE impacts B2C sales interactions, a focus group was held with seven top-level executives of firms competing in the retail jewelry industry (e.g., rings, diamonds, etc.) and one industry expert/consultant. The leaders and firms were chosen based on the criteria that their firms must (1) sell predominantly through trained salespeople who interact directly with customers and (2) have customers that engage with their firm, as evidenced through social media and firm-initiated CE activities outside of the face-to-face interaction. Participants were specifically invited to interview while in attendance at an international conference of jewelers. The discussion developed from a set of open-ended questions, which was structured, yet adaptable to the conversation. The resulting recorded comments were analyzed to identify themes referenced by multiple participants. Specifically, three interrelated themes emerged, which we describe, and compare to salient existing research, below.

Theme 1: Customer and Salesperson Incongruence

The first theme suggests that customers with higher levels of engagement, specific to the firm or marketplace, do not view the salesperson as a participant in their decision process. These customers often disengage if they feel a salesperson does not have a similar understanding of, and engagement with, the product, even in situations where the salesperson is well-trained, knowledgeable, and professional. The theme was troubling to our focus group, as comments indicated concern over how CE outside the sales interaction has a negative effect at the point of purchase when salespeople are not perceived as “worthy” of the customer’s business (e.g., lost sale, negative word of mouth, etc.). Some quotes from our focus group participants that embody this theme include:

“When customers engage with our salespeople it seems that our employee has to pass a test of sorts with the customer to demonstrate their ‘street cred’ in the area, which bears more weight than a more professional approach.” Rich M., nine retail locations

“Our salespeople know a lot about our products and what’s going on in the marketplace, but customers these days seem to discount a lot of that and will get frustrated and leave if the salesperson doesn’t ‘validate’ them.” Mike R., three retail locations

To develop this theme, we next look to literature that suggests that to be effective, salespeople should “broker knowledge” to their customers (e.g., Verbeke et al. 2011). In broad terms, knowledge brokering (i.e., being a knowledge broker, or KB) is defined as a process of translation, coordination, and alignment of perspectives in an effort to link and facilitate transactions between parties (Wenger 1998, p. 109). Inherent in brokering efforts is the potential for a salesperson to leverage their unique expertise to participate with customers in the value creation process. In sales, empirical support for the importance of the KB role is found in the Verbeke et al. (2011) update of the classic meta-analysis by Churchill et al. (1985) of sales performance drivers. The updated meta-analysis found that the most important driver of performance is selling-related knowledge, which is defined as “the depth and width of knowledge base that salespeople need to size up situations, classify prospects, and select appropriate sales strategies for clients” (Leong et al. 1989, p. 164). The second most important driver of performance is adaptiveness, which is defined as “the altering of sales behaviors during and across consumer interactions based on perceived information about the selling situation” (Weitz et al. 1986, p. 175). Verbeke et al. (2011) conclude that in the current knowledge economy, salespeople will be most effective in value creation when acting as KBs who leverage their selling-related knowledge to adapt to different customers.

Combining the literature with the first theme from our focus group raises a serious concern for the KB concept in practice. Specifically, our contributors explained that higher levels of external, pre-interaction customer engagement create situations where the salesperson’s input is not valued and that she/he is, therefore, not viewed as a participant in the value creation process. In other words, our focus group seems to suggest that external CE has taken the role of the salesperson in value co-creation. This view runs contrary to the new definition of selling as the “human-driven interaction between and within individuals and organizations in order to bring about economic exchange within a value-creation context” (Dixon and Tanner 2012). So while managers and scholars alike believe that the salesperson should play a critical boundary spanning role in value co-creation (Blocker et al. 2012), our focus group indicates that in a B2C setting, engaged customers are closed off to the salesperson’s inputs.

Two additional and related themes emerged from our focus group, which we detail in the next sections. However, given the importance of this identified problem, we now report that the final section of this chapter is devoted to developing a conceptual solution to this misalignment.

Theme 2: Customer’s Minds Are Made Up

The second, and related, theme suggests that salespeople have difficulty selling to engaged customers because customer minds are already made up when they finally enter the face-to-face interaction with a salesperson. While we might expect salespeople to appreciate this phenomenon, our focus group suggested that it often leads customers to choose an inferior product. This notion is evidenced by customers that simply do not want further information, regardless of the salesperson’s worthiness. In essence, the salesperson doesn’t really get a chance to prove themselves, let alone participate in value co-creation, as customers are quickly frustrated by the process and simply want to “get it over with.” Efforts by salespeople to find out more about the customer (i.e., by performing a general needs analysis as recommended in virtually all sales-training methodologies; e.g., Bolander et al. 2014; Rackham 1988) exacerbate, rather than help, the situation. In other words, and again, external CE disrupts attempts to engage in CE during the face-to-face interaction. Some quotes from our focus group participants that embody this theme include:

“Most of our customers tell us exactly what they want and expect that we will provide no input into the decision.” Dylan T., five retail locations

“It is like they are shocked that salespeople have something to say, their friend told them they could get X for Y and that is the end of the story.” Eric N, eleven retail locations

We again introduce literature as a basis to inform this theme. Several salient theories could be utilized to address this topic (e.g., involvement, consumer knowledge, information processing, etc.). However, to inform our study we turn to regulatory focus theory (Crowe and Higgins 1997), which tells us that consumers pursue pleasure and avoid pain in the pursuit of a goal (like making a purchase) and adopt one of two regulatory foci (prevention vs. promotion) during goal pursuit (Liberman et al. 1999). A prevention focus characterizes one who views goals as obligations or duties (Carver and Scheier 1998) and would lead a customer to become apprehensive when they feel deterred from fulfilling their duty and/or when interference is suspected (e.g., when they perceive that a salesperson is trying to change their mind). Alternatively, a promotion focus characterizes one who is focused on advancement and attainment of new information (Xie and Kahle 2014) and instead of leading a customer to protect their pre-made decision, would lead them to learn all they can to ensure an optimal decision in the future. We suggest that customers with higher engagement levels tend to adopt a prevention focus, while less engaged customers tend to adopt a promotion focus.

Bringing together the literature and our B2C sales setting, we suggest that salesperson messages congruent with the customer’s goal pursuit produce pleasure (getting closer to goal attainment, or making a correct purchase), while those not in agreement cause pain (getting further from goal attainment, or delaying/redirecting purchase). Incongruent salesperson messages (i.e., those which cause pain in the form of confusion, doubt, etc.) can lead a customer to depart the sales interaction altogether. Further, regulatory focus proposes that the consumer’s interpretation of the rightness or wrongness of an influence attempt will lead to strong judgments (Vaughn et al. 2009), which strengthens their resolve to depart an interaction when pressured.

These points culminate in the idea that because a customer is engaged externally, and before any in-person interaction, the efforts of salespeople to engage during the interaction are greatly undermined. To illustrate, consider a customer who is highly engaged and has made up their mind before meeting with a salesperson (recall that industry reports reveal that consumers are entering sales interactions as much as 70% of the way through the decision-making process (e.g., Microsoft 2015). The customer has drawn upon different engagement touchpoints to identify important decision criteria, or determinant attributes, and has formed a decision. This customer enters the sales interaction with a strong willingness to buy the predetermined product, which can be viewed as a duty or obligation to be accomplished (i.e., prevention focus). The next step in goal attainment is to purchase the product (not spend time talking to, or being persuaded by, a salesperson). As a result, the customer’s prevention focus limits the salesperson’s ability to act as a KB and co-create value because attempts to influence the customer will be viewed as a threat to goal attainment and engender a strong negative response.

With his or her mind made up, and prevention focus activated, the engaged customer would prefer a salesperson who functions as an order taker, not a KB. Of course, firms need to justify employing relatively highly paid salespeople as opposed to lower paid cashiers or even simply using an online store. So we see an interesting conflict where firms want their salespeople to be value-adding KBs, while customers (at least highly engaged ones) want the salesperson to get out of the way and let them fulfill their intended purchase. This theme provides some support for the doomsday prophets mentioned at this chapter’s outset. If increased means of engaging customers external to the sales interaction are leading customers to adopt a prevention focus, why do we need the salesforce? Or, from a positive perspective, what are the behaviors that might allow a salesperson to perform the KB role even with highly engaged customers? As previously foreshadowed, we will later explore this issue as part of our conceptual solution.

Theme 3: Customers Believe Themselves to Be Well-Informed

The third theme that emerged from the focus group suggests that customers who are more engaged with the firm and its stakeholders consider themselves well informed concerning market offerings from both the focal firm and its competitors, yet often are not. The participants indicated that, despite their engagement with the firm and marketplace, most customers typically overestimated their knowledge of the actual product. In addition, many customers were also described as having errors and/or omissions in their knowledge, which caused problems for salespeople . Some quotes invoking this theme include:

“Customers think they know everything from a few hours online and they assume that this ‘knowledge’ is more credible than a salesperson’s five or ten years working with the product.” George P., industry expert

“Customers come in and say things like, ‘I was watching this YouTube and it said that clarity (as one example) isn’t important.’ But, we know they are wrong, we’ve seen the video too – the video guy is selling a bad product. Doesn’t matter, the customer is always right, right – not!” Stacey L., five retail locations

This theme shows that not only are customer’s minds made up concerning their decision (as detailed in Theme 2), but also that they often overestimate their knowledge. According to our participants, engaged customers largely do not recognize knowledge deficiencies, resulting in problems for salespeople . They also stated that attempts to correct any deficiencies seem to threaten and further drive engaged customers away from the sales interaction.

This theme is highly related to the previous and, we suggest, also results from the prevention focus of the highly engaged customer. This point is also related to the salesperson KB concept and we suggest that it impedes a salesperson’s ability to act in the role of KB. Specifically, the KB role requires a salesperson to develop an understanding of their customer’s expressed and unexpressed needs, interpret them in regard to knowledge bases, and then present knowledge scarce to the customer. Scarce knowledge is characterized as information that consumers do not have access to (Verbeke et al. 2011). In other words, KBs add value to the sales interaction by knowing more than the EC, despite the latter’s prior engagement and information gathering, which is used to provide relevant missing information to customers. Scarce knowledge can also address knowledge that the customer has that either is factually incorrect, or being interpreted incorrectly. For this type of scarce knowledge , the KB can provide correction for erroneous customer information (e.g., an incorrect mpg estimate in a car purchase situation). Or, consistent with the “Challenger Sales” model (Dixon and Adamson 2011) and/or “Provocation-Based” selling (Lay et al. 2009), the KB can provide correction intended to change or improve interpretation of information (i.e., challenge thinking). However, the prevention focus of customers with high levels of engagement impedes information exchange required for KB salespeople to effectively impart scarce knowledge .

In summary, our contributors expressed that customers highly engaged outside of the sales interaction have a sense of “entitlement” when they come to the retail location, based on their prior behaviors in regard to the firm. By entitlement we mean that higher levels of CE typically result in the customer having a specific purchase in mind when they enter the sales interaction. For these customers, when a salesperson has a credible recommendation for a superior product/service, it is often ignored by the customer in favor of the customer’s pre-interaction product choice. Recommendations are ignored largely because the customer thinks they know more than the salesperson, and hence the salesperson is perceived as irrelevant, or worse, a threat. This notion was unanimously viewed as a negative aspect of customer engagement, as the customer’s purchase of the inferior choice often leads to negative CE with other customers (e.g., negative reviews) and the firm (e.g., complaints) soon after purchase. Efforts to determine positive ways that salespeople could overcome this problem provided some interesting responses, but no clear theme emerged as a consistent solution.

For B2C firms that rely on salespeople , the phenomenon described poses an obvious problem. On one hand, the leaders we interviewed desire to propagate CE as a positive way to co-create value with customers. On the other, their salespeople seem hindered by high levels of it. So, despite what might be expected, our focus group comments indicate, and we suggest, that for B2C complex product sales, CE outside of the transaction has a dark side in need of a solution. In response, we use the three themes developed by our focus group to develop a theoretical basis to help remedy this problem.

Proposed Solution

The themes described by our focus group participants do not bode well for salespeople of firms that promote CE outside of the sales interaction. Yet, most agree that promoting CE behaviors is positive for firm performance . And, regardless of if a firm actively promotes CE, most agree that customers will seek out engagement with the marketplace, if not the firm directly. Thus, we conclude this chapter by proposing some solutions to this dilemma. But first, we add that the comments provided by our focus group likely reflect a larger issue in sales, which simply put is that B2C sales interactions are rapidly changing. Many firms that experienced positive results from sales activities in the past are not assured that those same approaches will be effective today. Thus, our proposed solutions are theoretically based on the mechanisms that underlie the current problem. As identified, we suggest that in B2C sales, the regulatory focus of customers is the main underlying theme. Thus, we focus specifically on how a salesperson performing the KB role can address these problems based on regulatory focus theory.

Research on prevention- focused customers indicates that while those with a prevention focus are not interested in new, general information, they will elaborate on, and be receptive to, item-specific information (Zhu and Meyers-Levy 2007). Item-specific information addresses the few determinant attributes that the customer used to arrive at a decision. We suggest that this element of regulatory focus theory is directly related to how the salesperson, acting as a KB, can impart relevant scarce knowledge that addresses item-specific, determinant attributes. The issue is that attempts to uncover the determinant attributes of prevention-focused customers are counter-productive and will deter these customers from their goal, which may cause them to depart the sales interaction. Thus, we turn to a brief discussion of a new approach to needs analysis that we expect to be effective for prevention-focused customers.

We begin by suggesting that the KB task of “discovering expressed and unexpressed needs” is too general of an approach in a B2C sales interaction. There is no dispute that it is important to understand the needs of the customer (Moncrief and Marshall 2005). In fact, for frontline employees, this understanding is critical because the needs of customers are varied (di Mascio 2010; Plouffe et al. 2016) and can be the difference between success and failure (Homburg et al. 2009). To gain an understanding of needs, salespeople are trained to conduct needs analysis (Bolander et al. 2014). However, the current study argues that assessing customer needs through a “traditional” needs analysis is not an optimal starting point for consumers that are highly engaged with a firm. Rather, we suggest that needs analysis is precisely the area where KBs need to change their sales approach. For highly engaged customers, who have largely identified their needs prior to entering a sales interaction, we expect that needs analysis will threaten customers and cause their premature departure from the sales interaction (Zhu and Meyers-Levy 2007). Thus, we propose that KBs should conduct determinant attribute analysis , which we define as “developing a holistic understanding of customer prioritized and self-identified determinant attributes, which reflect their needs.”

This enhancement and clarification of the KB concept—to include the task of determinant attribute analysis —is consistent with the “sales profile” of a KB outlined by Dixon and Tanner (2012). They suggest that KBs need to take a global view of the customer’s situation to develop an understanding of their needs and information about those needs. In a traditional needs analysis, the salesperson may use a process, such as SPIN Selling (Rackham 1988), that starts with a general needs assessment that narrows through different question types to determine more specific needs. In settings where customers are unsure of their needs, or the potential solutions to those needs, this approach has proven merit. However, we propose that in settings where the customer perceives their level of awareness of alternatives/outcomes to be high, resulting in a predetermined solution choice, a more concise method is required. In this situation, we suggest that a salesperson essentially dispense with the niceties and quickly “cut to the chase.” Of course, “cutting to the chase” must be done using selling-related knowledge (i.e., in a tactful way). For salespeople , it is important to determine if the customer is actually an expert, or simply informed. Often, customers think they understand a complex situation with greater depth than they actually have (Rozenblit and Keil 2002). In these situations, it is suggested that salespeople ask customers what they know about the product and to explain what attributes are most important to them. This simple approach is in response to the comments of our focus group, which indicated that customers want to be validated, understood, and listened to, but not sold. This approach also allows for quick identification of knowledge gaps and misinterpretations. We propose that an attribute analysis approach is a means to quickly get to the core of the customer’s needs, and information about those needs, that will increase the potential for value to be created.

But, quickly understanding the determinant attributes of a customer with high levels of engagement is just the start. After identifying determinant attributes of this type of customer, the KB manifests his or her understanding by providing only attribute-specific information back to the customer (i.e., building “street cred”) because such messages will be considered for their underlying merit by highly engaged, prevention-focused customers. To illustrate, consider a customer who enters a sales interaction to purchase a smartphone. Like most complex products, smartphones have many technical elements that can be considered during purchase decisions. Assume the customer’s determinant attributes concern battery life, image quality, and charging time. Using a general approach, the salesperson who spends time talking about data download speeds, pricing plans, and extended warranties will simply irritate, and perhaps drive-away, the customer. But, if the KB first develops an understanding of the customer’s determinant attributes, then information specific to these attributes can be adaptively articulated and presented (as per Spiro and Weitz 1990). According to regulatory focus theory, this approach allows for the potential of customer value creation and firm value appropriation. We, therefore, propose that providing attribute-specific information , determined from an attribute analysis, is the first step for a salesperson to not only act as a KB, but also to be effective in creating value with highly engaged customers, as represented by ongoing engagement behaviors and purchase.

We next turn to the idea of scarce knowledge and suggest that KBs are most likely to create additive value when they present not only attribute-specific information , but also scarce knowledge . We define additive value as being realized when the customer accepts a KB’s recommendation (specifically, a recommendation counter to their initial choice). To elaborate, no scarce knowledge is presented when a KB determines the customer has complete information in comparison to her/his knowledge base (i.e., there is no scarce knowledge to add). In this scenario, value may exchange (i.e., order taking) but is not expected to be increased (i.e., persuasive, value-added selling). In other words, the customer purchases what she/he intended and, while not derailing the exchange, the salesperson doesn’t add any marginal value. However, when the KB determines that the customer has deficient information, we suggest that salespeople can create additive value by providing attribute-specific and scarce knowledge. Thus, we propose that scarce knowledge acts as a moderator of the relationship between attribute-specific information and engagement outcomes. This interaction should result in acceptance of KB recommendations and higher levels of engagement outcomes (e.g., word of mouth, etc.).

To illustrate this moderating effect, recall the customer purchasing a smartphone. The KB has determined that battery life, image quality, and charging time are the customer’s key determinant attributes. Next, the KB digs deeper by exchanging information to determine missing or incorrect information concerning the attributes. Assuming that missing or incorrect information is present, the KB can then present scarce knowledge that is attribute-specific. The culmination of such information exchange is likely a product/service recommendation, which draws upon the attribute-specific holes in the customer’s knowledge. We expect that this interaction is the best way for salespeople to be effective as KBs, allowing them to co-create value with highly engaged customers. Thus, firms that can train their salespeople to “cut to the chase,” “get specific,” and “fill gaps” with the information they exchange are likely to overcome the negative phenomenon outlined in this chapter.

The key challenges and proposed solution outlined in this chapter should be considered an important starting point for advancements in this area. Other engagement outcomes of KB activities should be examined such as cognitive dissonance (increases or reductions), perceptual changes in relation to the firm’s other CE activities (i.e., positive vs. negative), brand allegiance and/or switching, and, of course, sales performance. Additional moderators should also be considered, such as consumer persuasion knowledge, firm positioning of salespeople (e.g., Apple’s “genius bar”), and/or traditional salesperson characteristics that affect performance (e.g., gender, likeability, etc.). Also, important topics, such as how price differences, information types, and perceived risk affect acceptance of KB recommendations, should also be studied. Continued research in this area is encouraged because the prevalence of highly engaged customers, and their impact on sales interactions, is expected to intensify as engagement opportunities become even more ubiquitous for firms and customers.

References

Beatty, S. E., & Smith, S. M. (1987). External Search Effort: An Investigation Across Several Product Categories. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(1), 83–95.

Blocker, C. P., Cannon, J. P., Panagopoulos, N. G., & Sager, J. K. (2012). The Role of the Sales Force in Value Creation and Appropriation: New Directions for Research. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 32(1), 15–27.

Bolander, W., Bonney, L., & Satornino, C. (2014). Sales Education Efficacy Examining the Relationship Between Sales Education and Sales Success. Journal of Marketing Education, 36(2), 169–181.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1998). On the Self-Regulation of Behavior. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Churchill, G. A., Jr., Ford, N. M., Hartley, S. W., & Walker, O. C., Jr. (1985). The Determinants of Salesperson Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 22(2), 103–118.

Crowe, E., & Tory Higgins, E. (1997). Regulatory Focus and Strategic Inclinations: Promotion and Prevention in Decision-Making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 69(2), 117–132.

di Mascio, R. (2010). The Service Models of Frontline Employees. Journal of Marketing, 74(4), 63–80.

Dixon, M., & Adamson, B. (2011). The Challenger Sale: Taking Control of the Customer Conversation. New York: Penguin.

Dixon, A. L., & Tanner, J. F., Jr. (2012). Transforming Selling: Why It Is Time to Think Differently About Sales Research. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 32(1), 9–13.

Economist. (2015). Death of a Car Salesman. Available at http://www.economist.com/news/business/21661656-no-one-much-likes-car-dealers-changing-system-will-be-hard-death-car-salesman. Accessed 14 Sept 2015.

Hoar, A. (2015). Death of a (B2b) Salesman. Available at http://www.forbes.com/sites/forrester/2015/04/15/death-of-a-b2b-salesman/#708d38ed4e44. Accessed 12 Aug 2016.

Homburg, C., Wieseke, J., & Bornemann, T. (2009). Implementing the Marketing Concept at the Employee-Customer Interface: The Role of Customer Need Knowledge. Journal of Marketing, 73(4), 64–81.

Kumar, V., & Pansari, A. (2016). Competitive Advantage Through Engagement. Journal of Marketing Research, 53(4), 497–514.

Kumar, V., Aksoy, L., Donkers, B., Venkatesan, R., Wiesel, T., & Tillmanns, S. (2010). Undervalued or Overvalued Customers: Capturing Total Customer Engagement Value. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 297–310.

Lay, P., Hewlin, T., & Moore, G. (2009). In a Downturn, Provoke Your Customers. Harvard Business Review, 87(3), 48–56.

Leong, S. M., Busch, P. S., & John, D. R. (1989). Knowledge Bases and Salesperson Effectiveness: A Script-Theoretic Analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 26(2), 164–178.

Liberman, N., Idson, L. C., Camacho, C. J., & Tory Higgins, E. (1999). Promotion and Prevention Choices Between Stability and Change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1135–1145.

Microsoft. (2015). Always Be Closing: The Abc’s of Sales in the Modern World. Available at www.microsoft.com/en-us/dynamics/always-be-closing. Accessed 18 Feb 2016.

Moncrief, W. C., & Marshall, G. W. (2005). The Evolution of the Seven Steps of Selling. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(1), 13–22.

Plouffe, C. R., Bolander, W., Cote, J. A., & Hochstein, B. (2016). Does the Customer Matter Most? Exploring Strategic Frontline Employees’ Influence of Customers, the Internal Business Team, and External Business Partners. Journal of Marketing, 80(1), 106–123.

Rackham, N. (1988). Spin Selling. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rozenblit, L., & Keil, F. (2002). The Misunderstood Limits of Folk Science: An Illusion of Explanatory Depth. Cognitive Science, 26(5), 521–562.

Spiro, R. L., & Weitz, B. A. (1990). Adaptive Selling: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Nomological Validity. Journal of Marketing Research, 27(1), 61–69.

Van Doorn, J., Lemon, K. N., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P., & Verhoef, P. C. (2010). Customer Engagement Behavior: Theoretical Foundations and Research Directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 253–266.

Vaughn, L. A., Hesse, S. J., Petkova, Z., & Trudeau, L. (2009). “This Story Is Right On”: The Impact of Regulatory Fit on Narrative Engagement and Persuasion. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39(3), 447–456.

Verbeke, W., Dietz, B., & Verwaal, E. (2011). Drivers of Sales Performance: A Contemporary Meta-Analysis. Have Salespeople Become Knowledge Brokers? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(3), 407–428.

Weitz, B. A., Sujan, H., & Sujan, M. (1986). Knowledge, Motivation, and Adaptive Behavior: A Framework for Improving Selling Effectiveness. Journal of Marketing, 50(4), 174–191.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Xie, G. X., & Kahle, L. R. (2014). Approach or Avoid? The Effect of Regulatory Focus on Consumer Behavioural Responses to Personal Selling Attempts. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 34(4), 260–271.

Zhu, R., & Meyers-Levy, J. (2007). Exploring the Cognitive Mechanism That Underlies Regulatory Focus Effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(1), 89–96.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hochstein, B.W., Bolander, W. (2018). The Disruptive Impact of Customer Engagement on the Business-to-Consumer Sales Force. In: Palmatier, R., Kumar, V., Harmeling, C. (eds) Customer Engagement Marketing. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61985-9_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61985-9_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-61984-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-61985-9

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)