Abstract

In this introductory chapter, we examine the foundation of customer engagement (CE) by providing the scope and definition of the construct, its antecedents, consequences, and the various application contexts. We fill the gap in extant literature, as many aspects surrounding CE remain unexplored. The theory and conceptual framework of CE, as well as the moderators linking satisfaction and emotional attachment to direct and indirect contribution, are further discussed. We explore strategies improving the level of CE, the benefits of enhanced firm performance, and the toolkit to measure CE.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Customer Engagement: Introduction and Organizing Framework

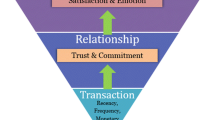

Managing customers has forever been the primary focus of firms. What has changed is how customers are managed. With the advent of customer and marketing databases, the strategies to manage customers have evolved from transaction to relationship marketing and now to customer engagement. This evolution is evident in the metrics used in the different phases of marketing. Till the early 1990s, managers analyzed customers’ transaction data to develop metrics such as past customer value , share-of-wallet, and recency, frequency, and monetary value of purchases. Managers used only these measures to design strategies to increase customer value and firm profits . However, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, firms realized that customers need more than transacting with the firm which led to managers shifting their focus from transaction marketing to relationship marketing. Firms then aimed at improving customer trust, commitment, and loyalty through better products, services, and loyalty programs. In this era, firms focused on retaining profitable customers by applying the metric of customer lifetime value (Kumar 2008).

Over the years, with the use of social media platforms for marketing activities, marketers realized that it is not enough to only understand how long the customer will stay with the firm but also to understand if there are other ways beyond purchases that customers can contribute to the firm. This led to the rise of the term Customer Engagement in marketing.

Consistent with the developments in the marketplace, this book of Customer Engagement Marketing covers a broad range of strategic issues regarding the antecedents and consequences of customer engagement. It also focuses on understanding customer engagement in different contexts and extending the concept of Customer Engagement. The book comprises 14 chapters which are organized into three parts (see Fig. 1.1) consisting of the antecedents, consequences, and the different contexts of customer engagement.

However, before we dive into the chapters, it is crucial to understand the basic foundation of customer engagement by focusing on the following questions:

-

a)

What is customer engagement?

-

b)

What is the theory driving customer engagement?

-

c)

How is it different from other customer relationship management constructs?

-

d)

Are there any benefits of engaging customers?

-

e)

Are there situations/contexts where customer engagement would be enhanced?

Understanding Customer Engagement

Engagement has been discussed over the past century with various interpretations in numerous contexts. In the context of social welfare, engagement is discussed as civic engagement, social engagement, community engagement, etc. In the business world, it is discussed in a contractual relationship context, and in management, as an organizational activity with the internal stakeholders. In the marketing domain, engagement is associated with the level of an active relationship that a customer shares with a firm and is termed as customer engagement (CE).

Customer engagement has been discussed extensively in the past decade in both marketing academia and the business world. It was the eighth most frequently used buzz word in business in 2014. In the business world, it has been considered a strategy, investment, listening to the customer’s voice, emotional connection, and interaction with the organization beyond what is necessary.Footnote 1 Gallup studies indicate that:

-

In the consumer electronics industry, fully engaged shoppers make 44% more visits per year and spend $84 more than a disengaged customer.

-

Fully engaged shoppers make 44% more visits per year to their preferred retailer than actively disengaged shoppers.

-

In casual and fast food restaurants, fully engaged customers make 56% and 28% more visits per month respectively, as compared to disengaged customers.

-

In the hospitality sector, fully engaged hotel guests spend 46% more per year.

-

In the insurance sector, fully engaged policy owners purchase 22% more types of insurance products.

-

In the retail banking industry, customers who are fully engaged bring 37% more annual revenue to their primary bank.Footnote 2

The above statistics highlight the importance of customer engagement. Customer engagement has been a topic of discussion in marketing academia from 2010 (Vivek et al. 2012; Kumar et al. 2010; Van Doorn et al. 2010; Kumar and Pansari 2016). There have been various discussions, definitions, and arguments about customer engagement. We present a snapshot of those conceptualizations in Table 1.1. The latest definition provided by Pansari and Kumar (2017) provides a holistic view of customer engagement.

Pansari and Kumar (2017) define CE as “the mechanics of a customer’s value addition to the firm, either through direct or/and indirect contribution.” The direct contribution consists of customer purchases, and the indirect contributions consist of incentivized referrals that the customer provides, the social media conversations that customers have about the brand, and the customer feedback/suggestions given to the firm. Based on the customer engagement theory proposed by Pansari and Kumar (2017), when a customer is satisfied with his/her relationship with the firm and has an emotional attachment to the firm, then it can be said that the customer is engaged with the firm.

Although there are multiple definitions of engagement, confusion prevails on other CRM constructs and CE. For instance, customer experience , customer involvement, customer satisfaction , customer commitment, and so on are frequently misinterpreted as customer engagement. To clarify, customer experience is the customer’s cognitive, affective, emotional, social, and physical responses to the entity, product, and service (Verhoef et al. 2009). This indicates that customer experience is the customer’s response to the firm’s actions, whereas customer engagement is the contribution the customer makes to the firm’s revenue, directly or indirectly. Similarly, customer involvement is the importance that the consumer places on the product/service depending on his/her need. Customer involvement occurs before the customer makes a purchase and customer engagement occurs after the customer has made an initial purchase and has had an experience with the firm. Several other CRM constructs are often misinterpreted as CE. These constructs, while related to CE, are quite distinct from CE. Table 1.2 provides an effective summary of how these are distinct from, yet related, to customer engagement.

Theory of Customer Engagement

Understanding the theory of customer engagement is a good way to enhance our understanding of the differences between customer engagement and other customer relationship constructs. The theory of engagement evolves from the relationship marketing theory in which the foundation is based on commitment and trust (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Previously, the primary purpose of relationship marketing was to establish long-term relationships with the firm, thereby promoting efficiency, productivity, effectiveness, and cooperation. A firm’s initial relationship with the customer was restricted to purchases, ensuring long-term loyalty, and continued patronage. However, this has evolved with the developments in the marketplace based on the ever-evolving needs and interests of the consumers. For instance, the current need of consumers is to always be connected with the firm through various social media platforms, interacting with other users of the product, and relying on customers’ evaluations of the firm. Many consumers even provide free review videos and feedback to the firm as their contribution to the firm. All of this indicates that customers have evolved from merely conducting transactions with the firm to developing a bond with the firm and its other customers. This relationship between the customer and the firm evolves only if the customer is satisfied with his/her existing relationship with the firm and is also emotionally connected with the firm. In other words, for customer engagement to exist, the customer should have a satisfied and emotionally connected relationship with the firm. However, this relationship evolves over time and varies from customer to customer based on the experience with the firm. This experience is positive only if the initial purchase made by the customer meets the expectations of the customer as shown in Fig. 1.2.

Figure 1.2 shows the conceptual framework and the theory behind customer engagement. As products and services are introduced, firms invest in marketing activities to create awareness. This awareness helps customers identify if the firm’s product and services fulfill a need. This awareness also sets an expectation in the mind of the customer. After identifying the need and expectations from the firm, the customer makes his/her initial purchase which creates an experience for the customer. This experience is positive if the firm meets or exceeds the expectations of the customer. Once the customer has a positive experience with the products and services of the firm, he/she would be satisfied with the firm which would induce repeat purchase. The positive experience that the customer has with the firm leads to positive emotions as discussed by Pansari and Kumar (2017).

The theory of CE states that if a customer is satisfied with the firm and has an emotional attachment with the firm, then he/she would be engaged with the firm in the form of purchases (direct contribution), referrals, influence, and feedback (indirect contribution). Specifically, satisfaction results in direct contribution, and emotional attachment results in indirect contribution. However, this relationship between satisfaction and direct contribution and emotion and indirect contribution is moderated by many factors—type of industry (service vs. product), type of firm (B2B vs. B2C), level of involvement, brand value, and convenience level.

For example, the nature of the industry (service vs. product) influences direct contribution (purchase). However, the impact of satisfaction on purchase is higher in the service industry because there is an immediate opportunity to recover from the service failure when the customer’s expectations are unmet. On the other hand, with a product, the chance of recovery is lower as the customer must wait until the next production cycle to repurchase—that is if they provided feedback to improve the product and if the feedback can be implemented. Moreover, the impact of satisfaction on purchase is enhanced if the firm is B2B. This is owing to the heightened focus on the product/service’s functionality and the approval from multiple decision-making units in a B2B firm. Additionally, the higher the involvement in purchasing a product, the higher the customer’s expectations and investment meaning the product is purchased less frequently than low-involvement products. Therefore, the impact of satisfaction on direct contribution is higher for low-involvement products because they are repurchased more frequently. Furthermore, the influence of satisfaction on direct contribution is greater for brands with low brand value as the level of expectations and chances of disconfirmation are low (high-brand-value products carry high expectations and disconfirmation) which leads to repurchase behavior as the level of satisfaction will be higher. Lastly, the impact of satisfaction on direct contribution is greater depending on the level of convenience provided by a firm. It is boosted if the availability and ease of use is high because it ensures possible product repurchase.

On the other hand, the relationship between emotions and indirect contribution is enhanced in a service industry (vs. product) since customers share their service experiences more often than their experiences with using a product, which in turn can lead to referrals and feedback for the firm. In a B2C firm (vs. a B2B firm), the impact of emotions on indirect contribution is enhanced due to the actions of consumers being based on emotions. Where there is emotional attachment, the consumers are more likely to recommend and participate in social media discussions regarding the product/service. In the case of high-involvement products (vs. low-involvement), the impact of emotions on indirect contribution is higher because consumers have invested time into researching the product and are willing to provide valuable feedback and recommend. In addition, for high-brand-value products, the impact of emotions on indirect contribution is higher due to the increased consumer expectations and attachment to the brand. On the flip side, this also leads to a greater negative effect in the event of disappointment. Lastly, the higher the level of convenience that the firm provides to its customers, the greater the impact of emotions on indirect contribution. This is due to the increased opportunity for customers to interact with the firm and provide referrals and feedback, as well as promote the firm on social media platforms.

Measuring Customer Engagement

For firms to accrue the benefit of CE, they should be aware of the toolkit to measure CE. All the components of CE can be measured with transaction data (Kumar 2013), except customer knowledge value, as it comprises the feedback and suggestions that the customers provide. The firm may only use the feedback that is specific to enhancing their product/service, and thus may not consider all of the customer’s suggestions. Tracking these suggestions and providing a monetary value is a challenge, which has not yet been fully explored in the literature (Kumar and Bhagwat 2010).

In spite of this, there is a robust Customer Engagement measure available where CE is measured as a second-order construct, with the components of CE (purchases, referrals, influence, and feedback) being the first-order constructs. Kumar and Pansari (2016) developed the CE scale, which comprises of 16 items. The scale is representative of all the dimensions of CE, as it is comprised of four items for each of the dimensions of customer engagement. The scale has been validated with multiple samples, and the overall scale reliability is 0.95.

Implementing Customer Engagement

The CE scale was used to measure CE in two time periods across 120 companies by Kumar and Pansari (2016) in 2013 and 2014. This sample of companies for the B2B sector comprised of multinational companies belonging to industries, such as lightweight metals, technology, engineering, manufacturing parts, and service companies including technology consulting services, computer hardware and software services, data/call centers, marketing research and analytics firms, advertising agencies, and media services. Some of the B2C companies included mail-ordering retail companies, and manufacturers of consumer products, electronics, and furniture, and mass media companies providing cable television, internet services, and telephone services, retail outlets, airlines, and rental businesses.

Based on the CE measures derived from the firms, Kumar and Pansari (2016) categorized the firm into four categories. A score of 16–31 on customer engagement indicates the lowest levels of engagement and is classified as “disengaged”; a score of 32–47 indicates low levels of engagement and is classified as “somewhat engaged”; scores of 48–63 on CE indicate that the customer is “moderately engaged” with the firm; and a score of 64–80 on CE indicates that the customer is fully engaged with the firm and are termed as “super engaged.” After the first period, the firms were categorized into these four categories and relevant strategies to improve their level of CE were suggested. These strategies to improve CE were based on the level of satisfaction and emotional attachment of the customer to the firm. In order to maximize both the direct and indirect contribution, companies must figure out how to manage both satisfaction and emotion in a positive way since satisfaction positively influences direct contribution, and emotions influence the indirect contributions of customers. The set of strategies, also referred to as the Customer Engagement Matrix, to manage satisfaction and emotion are based on the intensity of positive emotions (low or high) and the level of satisfaction (low or high).

For example, when customers display a lower state of emotions and satisfaction and continue to transact with the company, it could be that the customer is transacting with the company because of a necessity. Such customers are termed as “fill in need” customers (Pansari and Kumar 2017). For these customers, the firm will have to work hard and capture them beyond the “fill in need.” The firm must engage the customers by providing better service, understanding the customer’s needs and preferences, and the reasons why the firm is not the customer’s first preference. Firms can use appropriate strategies like discounts, promotions, and offer an improved quality of service to encourage the customers to transact more and form a strong relationship.

There could be some customers who have high positive emotions toward the firm but low levels of satisfaction. This could be because of low share-of-wallet, elevated expectations of quality, or disappointment with the quality. These customers are termed as “altruistic-focused” (Pansari and Kumar 2017), since they have high emotions toward the brand, despite being dissatisfied. For such emotionally attached customers, firms can use their attachment to their advantage to get more opportunities to meet the customer’s expectations. Companies can take advantage of the emotional attachment and better understand the needs of the customer and work toward reducing the customer’s dissatisfaction. Firms can segment these customers based on their level of emotions and use multi-level strategies to provide a better experience and improve the level of satisfaction.

Sometimes a customer may be satisfied with the firm but may not be emotionally connected with the firm. Such customers are aptly titled “value-based” (Pansari and Kumar 2017). As the name suggests, these customers focus on deriving maximum value from the firm. They would switch to any firm which provides higher value as they are not emotionally attached. Some managers may become complacent as this group of customers seem low maintenance as they already provide revenues to the firm. However, this would be short sightedness as it would be easy for the competition to lure such customers, and complacency from managers may hinder the objective of maintaining a long-term relationship with the customer. To maintain a long-term relationship with the customer, the firm has to have a deeper emotional connection with customers by duly recognizing them, providing personalized products, hosting events for them, providing better touchpoint experiences, being personal with them, and so on. All of these strategies may help the customers build an emotional attachment with the firm.

If the firm ensures that all its customers are satisfied with the relationship and are emotionally connected, then they can extract maximum value by using the appropriate strategies to enhance customer engagement. For instance, managers can use the “Wheel of Fortune” strategies by Kumar (2008) to increase the purchases of a satisfied customer. Each of the Wheel of Fortune strategies have been validated in the marketplace, with various firms generating an ROI of over eight to ten times after implementing these strategies. Some of the Wheel of Fortune strategies focus on resource allocation , pitching the right product to the right customer at the right time, and so on. In case of the indirect contribution (customer referrals, influence, and feedback), firms can provide incentives to their emotionally attached customers for providing referrals and use a social media metric like Customer Influence Value (Kumar et al. 2013) to offer financial incentives to its customers. Firms should also ensure that their infrastructure is seamless for customers to interact with them across various social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and so on. Firms should encourage customers to provide feedback by ensuring an infrastructure conducive to input by providing avenues such as feedback boxes, a page for feedback on the website, and so on. As an example of this approach, Dell Inc. has created the idea-sharing platform Idea StormFootnote 3 to encourage their customers to provide feedback and to collect new product/service ideas from the customer base.

Firms can use various strategies to improve their CE which will then improve firm performance . This was validated by Kumar and Pansari (2016) when they measured CE in the second year for the same 120 companies. Their model-free evidence indicates that in the B2B manufacturing sector, on average, the CE per firm improved from a score of 36 to a score of 48. They also show an average increase of 8.2% in firm revenues. However, this revenue increase cannot be attributed to customer engagement alone. In their study, Kumar and Pansari (2016) measure the combined effect of customer engagement and employee engagement (EE). However, when isolating the effect of CE and EE, the influence of CE on increasing firm performance was twice that of EE. In the B2B services sector, which was dominated by information technology and consulting firms, on average, the customer engagement scores declined from a score of 50 to 43, along with firm revenues, which declined by 5.2%. This decline was seen across the industry and was due to macro-environmental factors, rather than firm-specific factors.

In the case of B2C firms in the manufacturing sector, they observe the CE scores improving from 55 to 62 and the average profits improving by 3.4%. In the services sector for B2C firms, they note that the CE scores improved from 35 to 41, and the average profits improved by 5.6%. This implementation indicates that the customer engagement scale can be effectively used across industries.

Further, it is also true that customer engagement positively affects firm performance across industries. Despite a clear definition, theory, process, and benefits of engagement, there still remain a few questions which remain unanswered:

-

a)

How do product returns and customer loyalty affect customer engagement?

-

b)

How does personalization and customization of a firm’s offerings impact customer engagement?

-

c)

What are the various factors which can help build customer engagement?

-

d)

Does the impact of customer engagement go beyond firm performance ?

-

e)

Can the concept of customer engagement be extended and applied to the other stakeholders of the firm?

To answer these questions, the editors of this book solicited contributions from a pool of experts in the field to provide a better and in-depth understanding of customer engagement. The book is comprised of 14 chapters which are synthesized into a framework (see Fig. 1.3) which highlights the antecedents, moderators, and consequences of customer engagement.

This book provides strategies and an in-depth understanding of customer engagement. Overall, this book of Customer Engagement Marketing serves as an authoritative guide on customer engagement for professionals, researchers, and students.

Organization of the Book

This book is divided into three parts. Each part contains several chapters which deal with a specific theme related to customer engagement and answer a set of questions. Part 1 focuses on the antecedents of CE, Part 2 examines the consequences of CE, and Part 3 discusses the various application contexts in which CE can be applied and extended, as shown in Fig. 1.1.

Part 1: Antecedents of Customer Engagement

The first part of the book discusses in depth the antecedents of customer engagement. Chapter 2 is aptly titled “If You Build Right, They Will Engage: A study of Antecedent Conditions of Customer Engagement” by Vivek, Beatty, and Hazod. In this chapter, the author(s) identify two major sources of customer engagement, one originating from the firm and the other originating from the customer. They note that the customer engagement programs facilitated by the originating firm that are authentic, relevant to the consumer, and promote a true dialog between the firm and consumers would be successful. Further, they state that if the consumers are experience seeking, feel psychologically safe with the program, perceive the program to be meaningful, and feel psychologically available, then they are more likely to engage with the firm. The authors conduct two studies to capture practitioner and customers’ perspectives. Their findings indicate that successful CE relies on the presence of multiple factors (Chap. 2, titled “Conditions of Customer Engagement”) by the originating firm and internal tendencies of the individual consumer.

For CE to be successful, it is very important for the firms to understand the different stages of customer relationships and the impact of each of them on CE. In the next chapter (Chap. 3, titled “Measuring and Managing Customer Engagement Value through the Customer Journey ”), Venkatesan, Petersen, and Gussoni take the readers through a map-based view of customer engagement. In this chapter, the authors develop a framework for building the customer journey map based on customer engagement. They discuss the components of CE (CLV, CRV, CIV, and CKV) in the customer journey (pre-purchase, purchase, and post-purchase). The authors discuss the different customer relationship management streams like customer engagement, customer experience , and customer journey . In their framework, they recognize different stages of customer relationships (acquisition , growth, retention , and win back), and different stages of customer journey (pre-purchase, purchase and post-purchase). They discuss the various links in customer relationships which need to be further explored. For example, the link between customer retention , word-of-mouth, and influence is less clear, as are the best mechanisms for firms to use to engage with customers during their experiences. Their framework also highlights how customer experience would vary at each step of the CE process. For example, the pre-purchase phase of experience for acquiring high-lifetime-value customers would vary from that of the experience for acquiring high-influencer-value customers. The authors conclude by stating that firms will engage customers successfully when they can customize experiences that will appeal to a variety of preferences. Therefore, firms should develop customized strategies for enhancing customer engagement. This is discussed in depth in Chap. 4, which is aptly titled “Customer Engagement through Personalization and Customization ” by Bleier, De Keyser, and Verleye.

The authors state that when a firm personalizes, it takes the lead and tailors marketing activities to individual customers; and when it customizes, the customers take on an active role to partially adapt the marketing mix as per their preferences. In this chapter, the authors discuss the different stages of a customer’s life cycle (acquisition , retention , and attrition) with specific engagement goals at each stage and the customization and personalization strategies which the firms could use to tailor their marketing mix . Their findings indicate that the three main levels (mass, segment, and individual) of personalization are not mutually exclusive and can be combined. To modify strategies across the customer life cycle, relationship, and customer characteristics, certain tactics across the life cycle are discussed. Specifically, relationship characteristics include customer familiarity with the company and company familiarity with the customer. Customer characteristics include “customer role readiness ” and “customer trait reactance .” The authors suggest that for a successful strategy to achieve customer engagement, it is important that the level of autonomy for customization strategies and the level of granularity for personalization strategies both be aligned with customer characteristics, the level of familiarity, and the level of trust in the customer–firm relationship. Sometimes, regardless of personalization and customization , the customer may not be content with the final product and may return the product. However, product returns may not necessarily create a negative impact as they offer the firm one more opportunity to interact with the customer and fulfill his/her need.

In Chap. 5 titled “Managing Product Returns Within the Customer Value Framework,” Minnema et al. discuss product returns in the context of the customer value framework as well as the antecedents and consequences of product returns . The antecedents of customer product return decisions include the impact of product return policies, pre-purchase information effects, customer characteristics, and product characteristics. The consequences of product returns on the transactional and non-transactional aspect of customer behaviors include the impact on future purchase and return behavior and customer engagement behaviors. The authors conclude that product returns , in fact, have positive consequences on future purchase behavior and help foster loyalty and engagement toward the retailer.

Loyalty can help stimulate engagement if firms follow the personalized-level loyalty strategies as discussed by Bijmolt et al. in Chap. 6, which is aptly titled “Multi-Tier Loyalty Programs to Stimulate Customer Engagement.” In this chapter, the authors define and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of a Multi-Tier Loyalty Program (MTLP). They define MTLPs as “hierarchical structures that enable firms to prioritize customers based on past purchase behavior and target them accordingly.” They state that MTLPs help firms promote engagement among the most profitable customers by managing and fostering behavioral and attitudinal loyalty. An MTLP is a long-term investment which rewards customers based on their past, current, or future value to a firm. It has a predefined structure, rules, and procedures which help identify and target customers according to tiers. The authors also provide strategies (rewards , symbolic benefits, customer-company identification, and consumer learning ) through which firms can leverage MTLPs to stimulate customer engagement. They conclude by discussing the disadvantages of MTLPs, some of which are (1) the challenge of meeting customers’ expectations and sense of entitlement; (2) the resulting customer heterogeneity with customers not reacting satisfactorily to the differences in how they are treated; (3) the complicated dynamics whereby customers are promoted or demoted to new tiers; and (4) the ambiguities regarding how best to design the tier structure. MTLPs can be a tremendous asset to firms but only if marketing practitioners are aware of the potential drawbacks.

Chapter 7 titled “Happy Users, Grumpy Bosses: Current Community Engagement Literature and the Impact of Support Engagement in a B2B Setting on User and Upper Management Satisfaction” by Beckers et al. discusses the importance of support services for online communities in the B2B context. In this chapter, the authors discuss the growing online communities and managerial interest in facilitating web-based support services in the B2B setting. They examine how the value placed by users and upper management on receiving online customer support for community engagement varies. Moving from a traditional service support model, or a one-to-one support model, to an online support model, or a one-to-many web-based support model, allows customers to be passively or actively involved in support solutions. There are positives and negatives for both the customer and service provider in each model. The authors note that it is important for higher-level managers to ensure that the interests of the customer, organization, and individual are aligned. They hypothesize several theories about the effects of service request activity on satisfaction, knowledge consultation, and community support, testing each hypothesis through data collected from employees at various corporate levels. In the B2B context, it is not only the customer who plays an important role in the smooth functioning of the firm but also the partners of the firm. Hence, it is important to assess the engagement level of the partners as well.

Part 2: Consequences of Customer Engagement

In Part 2 of the book, the various consequences of customer engagement are discussed. Customer engagement has an impact on firm performance which has been widely discussed in the literature and the practitioners’ world. The impact of customer engagement on firm performance has been empirically validated by Kumar and Pansari (2016). In their study, they use a sample size of 120 companies across the B2B and B2C and manufacturing and services sectors, over a two-year period. Their results indicate that on average, after implementing the recommended customer engagement strategies , the average firm performance in terms of revenues increased. However, the impact of customer engagement goes beyond firm performance ; it also impacts the employees of the firm and is manifested through employee engagement and improved salesperson value, as discussed in Chaps. 8 and 9. In Chap. 8 titled “Customer Engagement and Employee Engagement: A Research Review and Agenda,” Mittal, Han, and Westbrook discuss “a review of extant research on the association between customer engagement and employee engagement, and the relationship of these two constructs with firm performance .” Customer engagement impacts employee engagement, and employee engagement impacts firm performance directly and indirectly. The authors stress the importance of clearly defining customer engagement and employee engagement, especially because employee engagement is often conflated with related constructs. Drawing from a recent definition developed by Kumar and Pansari (2016), the authors discuss engagement as primarily behavioral, “with an explicit acknowledgment that the behaviors are causally driven by customer and employee attitudes toward a firm.”

Earlier research was rooted in the service-profit chain (SPC) paradigm, in which employee efforts drive customer satisfaction , which in turn, drives the financial outcomes of the firm. The authors modify this approach with the help of stakeholder theory and the generalized exchange theory (GET). Empirically, the vast literature suggests a positive association between customer engagement and employee engagement, though it is clear that the relationship is moderated by a variety of circumstances. These moderators are explored in a section devoted to the context sensitivity of customer engagement and employee engagement. The authors analyze both the positive and negative outcomes of customer engagement and employee engagement.

Positive customer engagement drives customer loyalty, donations to charitable organizations associated with the firm, and so on, and negative customer engagement can result in dysfunctional customers who exhibit harmful behaviors. Finally, the authors highlight the methodological issues in examining customer engagement and employee engagement (i.e., the surfeit of single-firm studies, various measurement issues, etc.), and outline a few significant research gaps to be addressed in future studies.

In Chap. 9 titled “The Disruptive Impact of Customer Engagement on the Business-to-Consumer Sales Force,” Hochstein and Bolander identify the challenges which in-store salespeople experience with customers who have a high degree of firm and product engagement. The authors note that there is a conflict between the firm and the customers. The firms want to place a great deal of value on maintaining a salesforce of value-adding knowledge brokers , but high-engagement customers simply want order takers or automated purchasing, not specialized “knowledge brokers .” The authors held a focus group with executives in the retail jewelry industry to dive deep into this conflict. The findings of the focus group indicate that customers see salespeople as an obstruction or as irrelevant given previously acquired information. When customers’ minds are already made up when they enter the store, it is difficult for salespeople to create value for them. The authors invoke regulatory focus theory, that is prevention vs. promotion focus. They note that highly engaged customers are more likely to be prevention focused and view salespeople as obstructions. Customers often overestimate their own knowledge, presumably leaving an opening for salespeople to assist in the creation of scarce knowledge . The authors propose that salespeople identify the determinant attributes that the customers used to make their decisions, and impart relevant information within this context. This requires a change in how salespeople typically conduct needs analysis from a general to a more swift and concise approach that seeks to understand exactly which attributes are most important to the customer. The authors conclude by laying out steps for future research in this area.

Part 3: Application Context of Customer Engagement

Customer engagement can also be extended to various contexts like experiential brands, B2B, brand engagement, and emotional attachment. The next section discusses the various contexts in which customer engagement can be applied. In Chap. 10 titled “Creating Stronger Brands through Consumer Experience and Engagement,” Calder et al. address the conceptual distinction between materialistic/transactional brands. They discuss experiential brands as brands which engage with customers via personal, memorable experiences that transcend basic product attributes and ideally align with the customer’s larger personal goals. Citing relevant literature in this stream, the authors define an “ experientially engaging brand” as “one in which consumers make specific cognitive, emotional and behavioral investments for the purpose of gaining a valued experience from interacting with the brand.”

Given this overview of the extant literature, the authors tackle the question of whether experientially engaging brands perform better than transactional/materialistic ones. Though brands can function both materialistically and experientially, studies have relied on consumer perception to arrive at the conclusion: “…the consumption of experiences tends to generate greater happiness than the consumption of more transactional offerings.” Citing the limitations of this line of research and the aforementioned conceptual fuzziness of these two types of branding, the authors propose a research approach that emphasizes a consumer’s ability to classify a purchase as either materialistic or experiential depending on his/her focus.

The authors propose a model of self-control to advance contemporary understanding of why experientially engaging brands generally perform better than materialistic ones. Three hypotheses are generated that together focus on the capacity of experiential brands for alignment with consumers’ higher-order goals. By the same token, a materialistic brand can fulfill a lower-order goal at the expense of higher-order goals—the materialistic engagement can be successful and yet still create a negative impression on the consumer. The authors conclude the chapter by discussing engagement within a social media context, and how this line of inquiry can be developed in the future.

In Chap. 11 titled “From Customer to Partner Engagement: A Conceptualization and Typology of Engagement in B2B,” Reinartz and Berkman analyze specific properties of business markets like the derived character of demand or formalization, the rationality of exchange, and so on, and discuss their impact on the phenomenon of customer engagement. They argue that the concept of customer engagement should be extended to partner engagement to reflect the complexity and network character of value chains in the business markets. They also develop a typology of partner engagement behaviors in business markets and deliberate upon the differences in the levels of organizational engagement and individual engagement, the underlying relational factors, as well as special cases. They conclude by drawing specific implications for B2B managers and provide avenues for future research in the domain of partner engagement .

The last two chapters (Chaps. 12 and 13) discuss situational engagement and emotional engagement. In Chap. 12 titled “Engaging with Brands: The Influence of Dispositional and Situational Brand Engagement on Customer Advocacy,” Liu et al. discuss situational engagement and its relationship with brand engagement. They examine the influence of dispositional brand engagement on customer advocacy, as mediated through situational engagement with a specific brand. They also provide empirical validity for their framework. Their results show that brand engagement has a stronger influence on situational brand engagement than does brand schematicity . They also note that affective and behavioral engagement with a specific brand had an equal and positive impact on consumers’ advocacy for the brand. They conclude by providing theoretical and managerial implications for their study.

In Chap. 13 titled “The Emotional Engagement Paradox ,” Aksoy et al. examine how customers’ word-of-mouth (WOM) behaviors differ depending on the level of emotional engagement, or level of emotional arousal, toward brands across different industry categories. Their study links the emotional engagement level data to WOM behavior across different channels for 3022 US consumers. They draw distinctions in WOM behaviors between brands with different levels of emotional engagement using a simple exploratory means analysis on a limited sample of 696 respondents. Their findings provide insights signifying that positive/negative emotional engagement is associated with positive/negative WOM behaviors. Their study also shows that the highest levels of positive/negative online WOM and the most family and friend recommendations occur for customers having both positive and negative emotional engagement, which is also associated with the highest levels of self-brand connection. The authors conclude by providing implications for researchers and managers, and identifying a need for future research to determine whether the share of engagement reflects a managerially relevant outcome.

Conclusion

Collectively, the different chapters of this book provide a holistic picture of customer engagement marketing in various contexts. It provides an in-depth understanding of and clarity on customer engagement as it discusses the scope and definition of the construct, its antecedents, consequences, and the various contexts to which customer engagement can be applied. Although there has been some discussion on customer engagement, the conceptual framework of customer engagement (Pansari and Kumar 2017) is empirically validated only partially. It would therefore be interesting to understand and empirically validate the impact of marketing activities on customer engagement. This can be done by understanding the various marketing activities of the firm like advertising (online/offline) and promotions (free samples, coupons). Researchers could focus on empirically testing the complete process of the customer journey from the pre-purchase, purchase, and post-purchase stage as discussed in Chap. 3. They could then empirically test if customer engagement is part of the journey or if it is an outcome of the holistic customer journey .

This book has demonstrated various antecedents and outcomes of customer engagement. It would be thought-provoking to explore the antecedents and consequences of CE using other firm-controlled activities like innovation. For example, it would be especially interesting to explore whether product creativity affects customer engagement. Does this relationship vary based on the levels of creativity? Do engaged customers respond differently to new products of the same firm? It would be exciting to study these in the context of the fast-changing technology space where there is a creative product introduced almost every week.

Customer engagement has greatly benefited companies in the United States as demonstrated by Kumar and Pansari (2016). Would it help companies across the world? Can the existing customer engagement framework be applied to all the firms across the world, or should it be modified? The answers to these questions would help multinational firms launch new products and engage with customers as well as provide researchers with useful insights. The primary difference in the context of engaging customers between the United States and other nations would be influenced by the cultural and economic factors. The cultural factors of a country determine the tastes and preferences of consumers, and the economic behavior affects their ability to buy. It would be fascinating to observe the differences (if any) in the CE framework due to cultural dimensions. The integration of the CE framework with the cultural dimensions and the economic factors leads to some more intriguing questions like: Would the cultural dimensions affect all the components of CE, or only some? Would the economic conditions of a country affect only purchases or would it also affect the indirect CE dimensions? How would different industries across the world react to the CE framework?

Customers have always been important stakeholders to the firm. However, the other stakeholders like employees (as discussed in Chap. 8), suppliers, other partners (as discussed in Chap. 11), investors, society, and so on also play an important role in ensuring sustainable firm performance . Therefore, it would be beneficial to extend the concept of engagement to all the stakeholders of the firm and evaluate their impact on firm performance . Some questions that would then arise are—are all stakeholders equally important? How much should a firm spend on engaging all stakeholders? How much does each stakeholder contribute to firm performance ?

If the firms want to ensure that their customers are always engaged, then the firm has to ensure that engagement is an integral part of their organizational culture. Researchers could focus on developing the next strategic orientation for engagement similar to market orientation and interaction orientation. In the 1990s, Narver and Slater (1990) and Kohli and Jaworski (1990) focused on the concept of market orientation, which recommends that firms should not only focus on their customers but also on their competitors and on the process. Additionally, interaction orientation proposed by Ramani and Kumar (2008) reflects the firm’s ability to interact with customers and take advantage of the information obtained from them through successive interactions to achieve profitable customer relationships. Similarly, researchers could develop an Engagement Orientation approach focusing on effectively engaging all stakeholders and understanding the process of engaging all stakeholders and the benefits of the same.

This book is a great starting point for anyone who would like to discover the foundation of customer engagement and also understand its antecedents and consequences. There is also tremendous scope for researchers to explore customer engagement in depth and contribute to this growing body of knowledge.

References

Assacl, H. (1992). Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action (4th ed.). Boston: Kent.

Bowden, J. L. H. (2009). The Process of Customer Engagement: A Conceptual Framework. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 17(1), 63–74.

Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Juric, B., & Ilic, A. (2011). Customer Engagement: Conceptual Domain, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications for Research. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 252–271.

Bruner, G. C., II, Gordon, C., James, K. E., & Hensel, P. J. (2001). Marketing Scales Handbook (Vol. III). Chicago: American Marketing Association.

Delgado-Ballester, E., & Luis Munuera-Alemán, J. (2001). Brand Trust in the Context of Consumer Loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 35(11/12), 1238–1258.

Garbarino, E., & Johnson, M. S. (1999). The Different Roles of Satisfaction, Trust, and Commitment in Customer Relationships. The Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 70–87.

Gentile, C., Spiller, N., & Noci, G. (2007). How to Sustain the Customer Experience: An Overview of Experience Components that Co-create Value with the Customer. European Management Journal, 25(5), 395–410.

Hollebeek, L. (2011). Exploring Customer Brand Engagement: Definition and Themes. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 19(7), 555–573.

Kohli, A. K., & Jaworski, B. J. (1990). Market Orientation: The Construct, Research Propositions, and Managerial Implications. Journal of Marketing, 45, 1–18.

Kumar, V. (2008). Managing Customers for Profit: Strategies to Increase Profits and Build Loyalty. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall Professional.

Kumar, V. (2013). Profitable Customer Engagement: Concept, Metrics and Strategies. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications India.

Kumar, V., & Bhagwat, Y. (2010). Listen to the customer. Marketing Research, 22(2), 14–19.

Kumar, V., & Pansari, A. (2016). Competitive Advantage through Engagement. Journal of Marketing Research, 53(4), 497–514.

Kumar, V., Aksoy, L., Donkers, B., Venkatesan, R., Wiesel, T., & Tillmanns, S. (2010). Undervalued or Overvalued Customers: Capturing Total Customer Engagement Value. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 297–310.

Kumar, V., Bhaskaran, V., Mirchandani, R., & Shah, M. (2013). Practice Prize Winner – Creating a Measurable Social Media Marketing Strategy: Increasing the Value and ROI of Intangibles and Tangibles for Hokey Pokey. Marketing Science, 32(2), 194–212.

Kumar, V., Luo, A., & Rao V. (2015). Linking Customer Brand Value to Customer Lifetime Value (Working Paper).

Mittal, B. (1994). A Study of the Concept of Affective Choice Mode for Consumer Decisions. Advances in Consumer Research, 21(1), 256–263.

Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationships Between Providers and Users of Market Research: The Dynamics of Trust Within and Between Organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 314.

Moorman, C., Deshpande, R., & Zaltman, G. (1993). Factors Affecting Trust in Market Research Relationships. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 81–101.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

Narver, J. C., & Slater, S. F. (1990). The Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Profitability. Journal of Marketing, 54, 20–35.

Oliver, C. (1997). Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Combining Institutional and Resource-Based Views. Strategic Management Journal, 18(9), 697–713.

Pansari, A., & Kumar, V. (2017). Customer Engagement: The Construct, Antecedents, and Consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(3), 22–30.

Ramani, G., & Kumar, V. (2008). Interaction Orientation and Firm Performance. Journal of Marketing, 72(1), 27–45.

Van Doorn, J., Lemon, K. N., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P., & Verhoef, P. C. (2010). Customer Engagement Behavior: Theoretical Foundations and Research Directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 253–266.

Verhoef, P. C., Lemon, K. N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., & Schlesinger, L. A. (2009). Customer Experience Creation: Determinants, Dynamics and Management Strategies. Journal of retailing, 85(1), 31–41.

Vivek, S. D., Beatty, S. E., & Morgan, R. M. (2012). Customer Engagement: Exploring Customer Relationships Beyond Purchase. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 20(2), 122–146.

Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the Involvement Construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 341–352.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pansari, A., Kumar, V. (2018). Customer Engagement Marketing. In: Palmatier, R., Kumar, V., Harmeling, C. (eds) Customer Engagement Marketing. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61985-9_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61985-9_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-61984-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-61985-9

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)