Abstract

Against the backdrop of processes of internationalisation and differentiation in the education system, “being international” becomes a contested label used to distinguish schools and educational biographies. Using a qualitative case study of a private International Baccalaureate school in Germany, the chapter examines a school’s institutional codes concerning “being international” and how the students engage with these. Reconstruction is primarily based on longitudinal interviews with the school principal and students over the course of five years. Taking a praxeological stance, we argue that different modes of “being international” inform processes of distinction as well as integration and are closely tied to specific biographical spaces of experiences which are ultimately associated with unequal pathways, choices and perspectives.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Being international

- International schools

- Institutional codes

- International student biographies

- Longitudinal study

- Privilege

- Educational inequality

Introduction: International Schools and Developments in the Education System

International schools have long been part of the education system —in Germany and around the world. Given the historical legacy of first one and then a second world war, schools such as the United Nations School in Geneva (1924) were founded with the desire to further international understanding (Hill 2000: 32; Hornberg 2012: 118). Following this, the International Baccalaureate (IB) was founded in 1968 and has since increased its reach to all corners of the world. While the principle of “creating a better world through education” drove the IB , one of the reasons for its success was also the increasing importance and development of global markets and multinational corporations in the post-World War era requiring globally mobile workers , who in turn required an education provision that would meet the needs of their children as they moved around the world which would minimise changes and upheavals such mobility brought to their schooling. This created a need for certified international schools (Bartlett 1998: 77–78; Keßler 2016).

In Germany , since the millennium, we have witnessed a further expansion of international schools. These increasingly cater not only for globally mobile families but also for middle- and upper-class families resident long term in Germany . These latter parents are generally seeking an education that supports their efforts to facilitate opportunities for their children to be international (Helsper et al. 2016; Kotzyba et al. in this volume). The strategies used by parents to achieve this, how this corresponds to parental distinction work and how it might differ to that of other parents is a largely under-researched in Germany , hence the focus of our work. Today, the label international school functions as an umbrella term, referring not only to privately run schools which are often accredited by organisations such as the International Baccalaureate Organisation (ibo.org), but also to state schools that offer bilingual classes or are approved as European or UNESCO schools (Murphy 2000: 6; Köhler 2012). Over the last two decades, there has been a significant rise of “the” international school as an important feature of the (German) education system (Keßler et al. 2015). In their chapters for this volume, Deppe et al. and Kotzyba et al. offer new ways of defining internationalisation within German schools, including a focus on exclusivity and how these institutions and processes may positively or negatively privilege students (see also Zymek 2015).

International schools or international programmes within schools play an increasingly important role in creating points of differentiation and ultimately stratification within education systems. International schools cater for what Ball and Nikita (2014) describe as “global middle class” families and could be argued to be spaces of transnational (elite) education (Adick 2005; Hayden 2011; Krüger et al. 2016): they are, in the main, privately run, quite expensive to attend and sought out by professionally mobile parents working in senior management positions of global companies. We argue that even “traditional” international schools in metropolitan areas are today increasingly being accessed by affluent (German) families who might choose these schools above others for reasons different from their globally mobile working counterparts (Keßler 2016). Resnik discusses an international school education as an alternative for parents looking “to ‘purchase’ the kind of education and credentials that will ensure their children secure a pathway into the global market place” (Resnik 2012: 294–295; Phillips 2002: 170).

There are also a rising number of state schools offering the IB curricula. In Germany , there were 44 schools offering the IB curriculum in 2011, which increased by 60% in five years to 73 schools in 2016 (an increase from 28 to 46 in the private school sector, and from 16 to 27 in the state school sector, source: ibo.org). State schools mainly offer the IB diploma programme alongside the German Abitur, while private schools usually offer the primary and/or middle years IB programme as well as the IB diploma programme. This can be explained in part by the high cost of offering those curricula, which at state schools usually have to be funded by the parents or other funding sources accessed beyond the federal funding provision . Additionally, in Germany , the law governing education does not allow students at state-run schools to replace the Abitur with the IB ; so students have to study for both, which constitutes a considerable burden for those young people choosing this path. Hornberg and Pawicki (2016) assume that students completing the IB at state and private schools are likely to differ in terms of background and possibly motivation for their study choices. Such differences could be important in understanding the education and production of different elite groups in the future. Interestingly, the state does not actively promote the IB (unlike the Ecuadorian case as highlighted by Prosser in this volume or Resnik’s (2012) analysis of the UK context). We would argue that the emergence of the IB within state secondary schools is a response to the development of greater competition within the education system and is strongly shaping the development of new hierarchies within German secondary education (Keßler et al. 2015). Thus, as Resnik (2012) argues, the presence and growth of “traditional,” largely privately run IB schools in the German context suggests that these schools have played the role of trendsetters in processes of internationalisation that have affected the German educational landscape and have led—as argued by Deppe et al. (in this volume)—to a standardisation and expectation of internationalisation within education.

Being international is a contested concept and can be defined and implemented in various ways across different schools and by different school or education actors. Using a case study of a privately run (i.e. fee-paying) IB school in Germany , we examine its institutional codes in relation to being international and how students engage with these positionings. 1 We are specifically interested in how different school actors’ own biographies shape their explicit conceptualisations and tacit knowledge of being international and how this shapes the educational choices, unequal experiences and outcomes for various students. Before presenting our empirical findings, we will outline the relevant literature and set out our guiding theoretical and methodological framework.

Empirical, Methodological and Theoretical Lines of Reference: Framing the Research Question

To date there has been little research in Germany on international schools. 2 Important reviews have been offered by Hornberg (2010) and Hallwirth (2013) on the development of international schools in Germany , while Köhler’s (2012) empirical study explores student experiences at such institutions with a focus on peer relations. Similarly, while transmigration research examines understandings of transnationality, processes of social inequality (Berger and Weiß 2008) and education (Nohl et al. 2009), the role of schools in building transnational careers and an understanding of the self as being international has not yet been a focus within the literature. The global expansion of international schools and curricula (Hayden and Thompson 2011a, b, 2012) has been documented in part, and Ball and Nikita (2014: 89) found that in 2013 there existed approximately 6710 English-speaking international schools worldwide which were attended by over three million students. With regard to the growing number of so-called host nation students attending these schools, Song (2013) as well as Koh (2014) analyse the extent to which international schools can be argued to contribute to growing inequality in the South Korean and Singaporean national education systems respectively.

Little attention has likewise been given to the school actors’ perspectives on being international. Kanan and Baker’s 2006 quantitative study of students at three international schools in Qatar found that almost all aspired to a university education in the English-speaking world and stated a preference for business or media studies, engineering, politics, law and medicine. Quantitative studies by Hayden and colleagues have examined students’, parents’ and staff perceptions of these schools and found that they articulated an ideological as well as instrumental motivation for pursuing such an education—with the balance between these two aspects differing across contexts: “the ideology underpinning international education is considered important, but it is still perceived necessary to ensure that students follow a curriculum and take examinations which will enable them to access university in a number of countries around the world” (Hayden and Thompson 1998: 553). Furthermore, students and teachers associated being international with characteristics such as “international mindedness”, “second language competence”, “flexibility of thinking” and “tolerance and respect for others” (Hayden et al. 2000). They understood international education as being concerned with other cultures and/or the broadening of their own horizons.

Despite this short overview of some of the relevant research published to date, there is, we argue, a lack of empirical research on the concept of being international, especially in the context of various schools today laying claim to being international (Helsper et al. 2016). The chapter therefore takes this gap as its starting point. We are especially interested in whether, and how, being international plays out in the institutional codes of an international school and likewise shapes the orientations of its students. Through a focus on a “traditional” international school, which arguably belongs to the “trendsetters” in internationalisation and the provision of education, we hope to offer some initial empirical insights and theorisations in relation to this critical question. We rely on praxeological approaches that link Bourdieu’s cultural theory with action theory (Bohnsack et al. 2010; Mehan et al. 1996; Reay 2004; Reckwitz 2004). Through such an approach, we consider milieu-specific experiences and socialising interactions within family, school and their peer world as central to the genesis of people’s habitual (educational) orientations (Bohnsack 2003: 68). We analysed school documents, ethnographic notes from observations and in-depth interviews with the principal at two points in time, two years apart. Based on a quantitative survey with students, who during the first phase were in the tenth grade and during the second phase of the study were in the twelfth grade, 3 we gathered information on their social and ethnic composition, school performance, peer networks and leisure activities. Then, using theoretical sampling we selected sixteen students to be involved in a longitudinal exploration of their experiences and ambitions as they moved from the tenth to the twelfth grade at the school, and then again, at a third point in time—two years after they had left school and were in their second year at university.

Our analysis of the qualitative data collected is based on the Documentary Method (Bohnsack et al. 2010) which was developed in part as a continuation of Mannheim’s sociology of knowledge and the ethnomethodology of Garfinkel and Bourdieu’s habitus theory. Following Mannheim, a distinction is made between communicative and conjunctive, rather tacit knowledge: “the documentary method aims at reconstructing the implicit knowledge that underlies everyday practice and gives an orientation to habitualised actions” (Bohnsack et al. 2010: 20). This procedure involves a multistage analysis of individual (or in other cases collective) narrated experiences and enables the reconstruction of both forms of knowledge—communicative and conjunctive (Bohnsack et al. 2010).

In what follows, we argue that being international is in various ways an integral part of the school’s everyday life. We also discuss the different articulations of being international which emerged from our discussions with students.

“What It Means to Be International”—Institutional Codes and Programmatic Claims

The international school which forms the focus of our case study was founded over 30 years ago. As most schools offering the IB curriculum from primary through to senior school, it is privately run and located in a metropolitan region in West Germany, where many international companies are based (Ullrich 2014; Zymek 2015; see also Kotzyba et al. in this volume). It was founded by non-German parents who were looking for an English-speaking school in the area. A school place costs up to €1500 per month, with about ten scholarships available at any one time. Students mainly work towards the International Baccalaureate (IB), which allows them to apply for universities abroad as well as in Germany . The school is attended both by children of internationally mobile workers as well as students who live permanently in the area.

In the two interviews, 4 the principal considered being international not simply as the ability to speak numerous languages or being in possession of dual citizenship but also:

if you describe yourself as (.) international … one thing is that you don’t consider people always as members of groups as Japanese or German … you see them as individuals with characteristics which might be common to members of groups but also characteristics which they share with other people just because they’re members of the human race … you can’t really be international unless you’re willing to consider differences and test your assumptions about the world … you need to be flexible and open minded (Interview 1).

Being international is understood as an attitude associated with individuality, reflexivity and tolerance. Differences are brought together and integrated with the common trait of belonging to the “human race.” Notions of the individual, self-reflexive learner also echo in the principal’s depiction of the ideal student:

I don’t know if there’s such a thing … some of the students that I work (3) best with … are sometimes students who have (2) problems or difficulties one way or another they might be academic they might be:: behaviour … it would be less interesting (3) to work in a school where everybody behaves perfectly (Interview 1).

Instead of praising accommodating students, he champions “confident, creative and critical thinkers” (Interview 1), even if this means they display more challenging behaviour.

This attitude of being international traverses all institutional codes reconstructed from the school’s educational offer: the focus on the individual learner, lifelong learning, academic excellence and world citizenship (reconstructed in Keßler et al. 2015). The first aspect ties in with the commitment of the IB’s programme to a pedagogy of letting individuals grow “through all domains of knowledge” (IBO 2015: 1). The principal says that if he and his colleagues were of the opinion that a family would be better off at one of the other international schools in the region, they would recommend this (Interview 1). The code of lifelong learning also plays a prominent role here. The principal talks in terms of an interconnected global world whose citizens must adapt to diverse changes: “We do all have to be lifelong learners whether we like it or not because technology brings lots of changes.” (Interview 1) Within this frame of reference, he describes the school as one that strives towards academic excellence. It is presented as a full-time school that prepares its students for prestigious universities worldwide. Its website publishes annual lists of the universities attended by its graduates and students’ average marks are presented as excellent.

A further educational code of the school is that it produces world citizens and international mindedness. These concepts remain largely vague, suggesting these notions may be taken for granted within the school’s culture . Part of this notion is the promotion of experiences of difference and openness to these within the school: social interactions with manifold others are incorporated in the school’s everyday life (Helsper et al. 2016). “Internationality” and “cultural sensitivity” are important terms used here—the school is presented not merely as a supportive space for coping with the migration situation of the families; the international setting is furthermore imagined as facilitating learning from and inspiring each other. Given the range of cultural backgrounds within the student and staff groups, the particular setting of the school becomes a prerequisite itself which supports further internalisation of being international. This seems to be one of the decisive differences between this kind of international school and other kinds of (state) schools who are seeking to orient themselves to the international (Helsper et al. 2016). 5 Being open to change, and tackling it in a productive manner, is described as a challenge that might not always be easy but is turned into something positive. The school is mapped out as being a source of inspiration and a motivation for continuous learning beyond the transfer of academic knowledge and as such as an “international community of learners” (Interview 2).

Apart from understanding being international foremost as an attitude (and embedded within the setting itself), the principal points to the school being an international one in the sense of its association with global actors such as the IB organisation and other networks like the New England Association of Schools and Colleges by which the school is regularly evaluated. This is imagined as a quality marker for international schools in general: the principal understands the IB diploma as a “good product” (Interview 1) setting the school apart from state curricula, which are perceived as being developed by state personnel instead of by educators (Interview 1). In this context, the diploma functions as a kind of symbol standing pars pro toto for the quality and situating it as better in comparison to other types of schools.

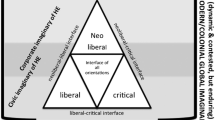

Summarising the main arguments made so far, we have suggested that the understanding of being international promoted by the school and school principal is semantically linked to an orientation of personal and institutional development and growth. Both dimensions are brought together in the school’s institutional codes . This interweaving of aspects allows for different readings: parallels can be drawn with progressive and also humanistic concepts of education, with a strong focus on individual learning, interconnectedness and the ability to adapt to lifeworld issues that might also be discussed as opening pedagogic possibilities for dealing with mobility and migration other than that of the positively privileged (Zymek 2015). Aside from this, the economic vocabulary associated with the depiction of the school’s distinctiveness (see also Prosser in this volume) as well as practices such as regular evaluations, the implementation of a mission statement or the notion of the lifelong learner are not only suggestive of a purely pedagogical ideal, but such understandings are equally driven by economic needs, such as the ability to adapt quickly to new conditions, thus still playing a role in the economisation of education. This allows the concept of being international to be interpreted as a self-mobilising strategy of educational actors (Bröckling 2007: 73; Masschelein et al. 2007). We argue that the IB diploma as a symbol of distinction as it is positioned against state-mandated and state-funded education is especially powerful. Our analysis suggests that this particular school’s interpretations and practices around being international allow for the creation of a space that promotes integration and the development of global understandings, while at the same time allowing their students to implicitly distinguish themselves as being superior in terms of their education, experiences and outlooks (see also Prosser in this volume).

The Students: Ways of Being International

In the following, we provide an overview of the general student body and the different motives they identified for choosing the school and how these are linked to notions of being international. We will then present in more detail two student perspectives on being international: a conscious involvement orientation and a more embodied, and therefore, naturalised approach.

The student body of approximately 1000 is comprised of young people from almost 50 different nationalities. The majority of the students was born outside Germany and they have only attended the school for a relatively short period of time. Since their parents tend to hold senior management positions within global companies in the region, school fees are usually paid for by employers. Most young people have moved across national borders at least once in their lives, and the majority can be described as highly mobile. The spectrum of mobility encompasses students like Abiram who came to Germany from Israel when he was six years old, or Vitória who was “born in Brazil … and [her] whole life people move a lot” (Interview 1) and who had already attended five internationally profiled schools in Asia and Europe before coming to Germany at the age of 16. Around 20% of students have a German passport. One of them is Charlotte who was born “in this city and … lived up to now in this city” (Interview 1, translated from German), has been attending the school since fifth grade and has never lived outside Germany . Meanwhile, Sandra has German citizenship like the rest of her family, but went to a school in the UK for six years because her parents moved there for work, before returning to Germany , again due to her parents’ employment. While Sandra might be German according to her passport, she has lived abroad for an extensive period of time, can speak more than one language and sees her future as not necessarily being in Germany .

Families have chosen the international school for different reasons. Most identify the desire to have broad-ranging experiences in an international education setting. In addition, families’ more specific motivations and understandings are shaped by their own spaces of experience (Erfahrungsräume) through which they have lived, and relate most strongly to the extent to which they have been transnationally mobile. Based on our analysis, we have identified four groups of families using this school. 6 The first group is comprised of mainly non-German, mobile parents seeking a curriculum which is taught and accepted globally, so their children can move and almost seamlessly continue with their education whenever they next move. The second group consists of binational families, where one parent has German citizenship , but these families tend to be quite mobile due to their work commitments as well. Parents in this group seem concerned that their children’s command of German is not strong enough for them to “survive” at a German-speaking school: Elizabeth, for example, first tried to attend a German-speaking school and explains “suddenly I had to do everything in German … German classics, … biology in German and history … and I just hated school” (Interview 2, translated from German). A third group of students are mainly German, have non-mobile parents, but are seeking an education for their children that will support future international mobility and participation in the global labour market. While this also holds true for parents among the first two groups, it is very clearly articulated by these parents as a belief that the international school will significantly support such transnational future projects in a way state schools would not be able to: “You have more options with the IB and I think many universities regard the IB as a higher degree than the Abitur or the American high school diploma (.) it helps” (Daniel, Interview 1, translated from German). The fourth group comprises mainly German young people, who following experiences of taking part in a school exchange programme, wanted specifically to continue pursuing a more international education, which led them to enrol in this international school. While these families’ motives were reconstructed from interviews with the students themselves, only the fourth group of young people articulated a strong sense of students themselves leading decision-making in relation to school choice (Keßler 2016).

Being International Between Conscious Involvement and Embodied Perspectives

Drawing on the interview narratives, we have reconstructed two modes of being international: a more reflexive engagement and a more embodied practice. We illustrate these with two case studies. While the first case study follows a student in an in-depth, longitudinal perspective, the second one focuses on pointing to differences and commonalities between the two. We chose two less internationally mobile students from our sample as we believe this allows us to highlight more clearly the contrasting perspectives on being international. These case studies also allow us to show the interweaving dimensions of internationalisation and inequality within education in the IB schools space—which we have argued can be seen as “trendsetters” in promoting and driving desires for, and commitments to, internationalisation across the wider field of higher secondary school education in Germany .

As mentioned above, we use the Documentary Method to differentiate between an individual’s explicit self-concepts and theories and the tacit knowledge that “guides” his or her action on a conjunctive level. The latter is formed through individual stratified milieu experience. We can trace this through a longitudinal perspective for our first case, that of Charlotte, and her being international by using the three interviews we conducted with her—when she was in Year 10, again in Year 12, and then two years post graduation.

Charlotte is German and representative of a third group of students we found at the school, who do not have any of the obvious international markers often associated with those attending IB schools. She joined the school at the beginning of the fifth grade. Her family had enough economic capital to finance a place for her at the school which already sets her apart from those children of mobile families whose employers pay the school fees (and without this provision might not have been able to afford the high school fees). Charlotte’s case highlights a central aspect of the first mode of being international: a generally high degree of reflexivity and explicit processing of ideas and concepts of oneself as being in a global world—especially as her position at such a school is not self-explanatory as she does not have a transnational biography , or require access to a curriculum that is available in other parts of the world. We argue that such an orientation was found for most of the German or binational students with relatively non-mobile biographies we studied.

In this particular student’s case, being international goes along with a relatively strategic pursuit of her own ambitions (Hayden and Thompson 1998: 553). For Charlotte, going to a private international school was about enabling future success: “It is best for any job (.) this international aspect … that one can speak English that one can internationally get along with people,” which in her view would not be available to her at a state school (Interview 7 1; also Resnik 2012: 298; Prosser in this volume). Experiences at the international school as well as in other spaces, formed a desire to explore the world and learn from these experiences—moving her engagement with the international beyond a purely strategic motivation. Being international was central to Charlotte’s narratives around school and university choice across the three interviews. Alongside strategic mappings concerning a network of international contacts that she felt the international school would provide for her future ambitions, she articulated an organic understanding that being international was something she needed to “preserve” and possibly “nourish further” (Interview 3) after leaving the setting of her international school. She understood that speaking English was a prerequisite to accessing international work contexts, as well as an imperative for being “drawn out into the world” in order to explore it (Interview 3).

During her interviews, Charlotte reflexively considered the privileged education context she was in and sought to distinguish herself from an “elitist clan” that consists of “a group of people who are very privileged … either been born into it or always strived to be part of something elitist,” who had lost touch with the “real world” and did not appreciate their privileged access to education (Interview 2) as anything but normal. As a German student whose family was able to finance her school place, a high degree of identity work was done in order to distinguish herself from those rich students she positioned as ungrateful. It was not that Charlotte did not want to belong to an elite professional group herself in later life (Interview 1) or that she did not already engage in exclusive lifestyle practices such as high-end partying (Interview 1, 3), but she was at pains to offer a reflection on her own privilege and desire to belong to a group of elite-reflexive, thoughtful world citizens , who sought to contribute to the world via their privileged position. This is where we understand her to identify closely with the institutional imagery of the international school which the principal articulated as well, and therefore her identity work occurs on the communicative as well conjunctive level: “They really teach us to become citizens in the world and … get along with fellow humans” (Interview 2).

The continued longitudinal perspective shows that this view of being international is not merely part of an explicit self-concept, but is actually guiding her action in the form of incorporated knowledge. She therefore enacted her orientations in order to take up studies at a prestigious university in a capital city outside Germany . Although she was not immediately offered a place at her first-choice university, she refused to accept this decision and kept getting in touch with the institution . She shared with us that “right before the start of the semester (.) they did accept me … they said that I remained on the ball” (Interview 3). This embodied attitude “of dreaming big” (Interview 3), that “if one really wants something, one can do it” (Interview 2), informed her actions through incorporated, tacit knowledge.

Our second, briefer case study is that of Gwyn, who we argue represents students who while not continuously mobile due to their parents’ employment, have a more deeply embedded international orientation due to their family biographies. Gwyn held non-German dual citizenship, but had lived in Germany since the age of six and attended the international school from that time onwards. His parents came from southern Europe, and his father had studied and worked in both Germany and North America before the family settled in Germany when Gwyn was still young. The migrant history of the family is also evident from Gwyn’s dual citizenship —that of a southern European country and American citizenship , as a result of being born there when his father was working in the United States. Gwyn speaks fluent German and has lived in Germany for most of his life. His family keeps in touch with their relatives in southern Europe and are socially part of an internationally diverse network of family and friends in Germany . Both parents studied at university and have considerable economic and cultural resources. While his parents do not represent the kinds of families who can be considered part of the global middle class (Ball and Nikita 2014), their investment in an expensive, international education stems from their desire to facilitate opportunities for Gwyn to pursue a transnational future should he wish to, which stems from their own personal experience of transnational mobility .

In contrast to Charlotte, Gwyn’s perception of himself as being international is much more embedded in his habitus —so much that it is difficult to find interview passages where he directly reflected upon this matter. Rather it became apparent during the interviews that he regards himself as a world citizen , who would study at an internationally renowned university. In contrast to Charlotte, being international was not a strategic decision that would best promote his future opportunities, but appeared to be an expectation that he would select a university from a global offer of possibilities and find the best match for his own personal interests. He did, however, specify that he would be seeking a warmer climate than the one he was accustomed to in Germany (Interview 3). He expressed surprise when he discovered that his university and degree choice might tie him to certain national contexts in the future: “Then I will probably need to do this here (.) because it would be difficult … the system [elsewhere] is different … and it would make no sense to break with this and go back well (.) I will probably … have to practice the job here [in the USA] (.) mmmh (3) I don’t know whether I like this plan” (Interview 3).

Against the background of his integration in extended, transnational family networks, attendance of an international school from an early age and involvement in community service projects in Africa through his school, Gwyn’s identification with the overall institutional guiding principle of being international and being a tolerant world citizen is a given, documented by his desire to study linguistics or anthropology at an American university as well as his views on inequalities in education across different school types and even national systems: “One needs to be grateful to visit such a good school … in this southern European country [anonymised] or at a Hauptschule [German secondary school enabling to take up an apprenticeship; highly stigmatised] … people do not have a future just because they do not attend a good school” (Interview 1).

Although he has lived in Germany since his childhood, Gwyn does not appear to face the same dilemma as Charlotte of having to distinguish himself from affluent, non-mobile (German) students. On the whole, these lines of distinction seem less explicit in the biographical narratives of students with considerable transnational experience and the significant cultural, social and economic capital it (re)generates. This stands in contrast to the narratives of people who feel obliged to explain their presence at the international school and their claims to being international more minutely as a result of their lack of mobility . We consider this argument further in the context of Maxwell and Aggleton’s (2010: 3) work on the “bubble of privilege ” and the ways in which privilege is integrated into young people’s attempts to create a sense of identity or self (Maxwell and Aggleton 2013). We have found that the biographical experiences of students in our study directly shape their tacit knowledge and orientations as well as explicit knowledge and theories of subjecthood. Given their resource-rich backgrounds in terms of economic, cultural and social capitals, these processes actively shape the forms of privilege they draw on to make sense of themselves in the world, and in doing so sustain the formation of privileged identities (as Howard et al. 2014 would argue). Thus, with Charlotte and Gwyn, we have demonstrated how their experiences inside and outside the international school shape their habitual orientations and understandings of their own privilege and how privilege is justified through the school’s institutional code which promotes the (morally upstanding) self-reflexive world citizen .

In our comparative, praxeological perspective, we can thus also add greater depth to the initial findings of Hayden and colleagues on being international by highlighting that the orientations of the students and their rapport with institutional claims to being international can differ greatly as a result of their respective biographical experiences and degree of integration in the different spaces they inhabit inside and outside of school. Thus, Charlotte and Gwyn represent two distinct modes of being international. Against this specific theoretical contribution we make here, we assume that these two modes could be further differentiated when considered alongside other individual’s biographies and experiences.

Conclusions

Drawing this chapter to a close, we would like to offer three conclusions based on our research. First, understandings of being international are evident across all institutional codes of the IB school we studied. It is associated with an attitude of reflexivity and tolerance which is further internalised through the experience of difference and openness promoted in the institution’s everyday settings. There are both tensions but also possibilities created through the integration of a humanist and economic imagery that the school articulates in its orientation to being international. This means that while possibilities for distinction (for the school and its students) are created, this is done by embracing (palatable) and desirable forms of “togetherness.”

Second, drawing on an analysis of the biographical accounts of the students, we proposed two modes of being international—a more conscious and a more incorporated engagement . We suggest that alignment with one or the other is linked to specific biographical experiences that form specific tacit knowledge. Third, by drawing together the principal’s and the students’ perspectives, Ball and Nikita’s (2014: 84) claim that international schools are educational institutions that seek to serve families belonging to the global middle class needs to be modified in our view. We have shown that IB schools in Germany are in growing demand from German families, with different combinations of high social, cultural and economic capitals (Phillips 2002; Brown and Lauder 2011; Song 2013). In this context, new hierarchies are emerging in the education system based on families’ access to, and uptake of, international schooling within Germany . We therefore argue that being international is facilitated by unequal experiences and ultimately (re)produces unequal opportunities. That is to say, it further embeds inequality , both in terms of current schooling experiences and future educational opportunities, but also through the kinds of orientations and values that are developed within young people. Based on our research we argue for the need for further examination of the lines of distinction between “international and national elites” (Resnik 2012: 305) at IB schools (see Keßler et al. 2015 for an analysis on this issue), and an exploration of how the provision of the IB at a state school may further exacerbate differences, or possibly in fact minimise these within national elite groups.

Glossary of transcript symbols

(.) | Brief pause in oral talk |

(3) | Three second pause in oral talk |

that | Stressed spoken word |

There = s | “Latched” talk |

wo:rld | Prolongation of the prior sound |

| Brief laughter |

| Text spoken laughing |

Notes

-

1.

This chapter is situated in the larger context of a longitudinal research project on exclusive educational careers of young people and the role of peer cultures . We examine the institutional presentations as well as (educational) pathways and orientations of young people at five Gymnasien (German upper secondary schools) with different claims to exclusivity. Here, we draw on data from one international school in our sample. First ideas were presented at a conference on internationalisation of education in Wittenberg, Germany (19–22 October 2015) together with Daniela Winter. We thank her and the editors for their helpful suggestions concerning earlier drafts of this chapter.

-

2.

See Resnik (2012) for an excellent overview of the state of research on international educational networks, policies, students and curricula. Here, we point primarily to studies that are especially important for this chapter.

-

3.

In Year 10, 94 of 101 pupils and in Year 12, 89 of 97 pupils, took part in the survey.

-

4.

A glossary of transcript symbols can be found at the end of this chapter.

-

5.

The other is here still part of a wider specific social group, but implies a different student and staff composition generally found at German (state) schools.

-

6.

For a more detailed reconstruction, see Keßler (2016).

-

7.

All quotations of Charlotte are translated from German, although the code often switches to English in all three interviews.

References

Adick, C. (2005). Transnationalisierung als Herausforderung für die International und interkulturell vergleichende Erziehungswissenschaft. Tertium comparationis, 11, 243–269.

Ball, S. J., & Nikita, D. P. (2014). The global middle class and school choice. A cosmopolitan sociology. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 17, 81–93.

Bartlett, K. (1998). International curricula. More or less important at the primary level? In M. Hayden & J. Thompson (Eds.), International education principles and practice (pp. 77–91). London: Sterling.

Berger, P. A., & Weiß, A. (Eds.). (2008). Transnationalisierung sozialer Ungleichheit. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Bohnsack, R. (2003). Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Bohnsack, R., Pfaff, N., & Weller, W. (2010). Reconstructive research and documentary method in Brazilian and German educational science. An introduction. In R. Bohnsack, N. Pfaff, & W. Weller (Eds.), Qualitative analysis and documentary method in international educational research (pp. 7–38). Opladen and Farmington Hills: Barbara Budrich.

Bröckling, U. (2007). Das unternehmerische Selbst. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Brown, P., & Lauder, H. (2011). The political economy of international schools and social class formation. In R. Bates (Ed.), Schooling internationally. Globalisation, internationalisation and the future for international schools (pp. 39–59). New York: Routledge.

Hallwirth, U. (2013). Internationale Schulen. In A. Gürlevik, C. Palentien, & R. Heyer (Eds.), Privatschulen versus staatliche Schulen (pp. 183–195). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Hayden, M. (2011). Transnational spaces of education. The growth of the international school sector. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 9, 211–224.

Hayden, M., Rancic, B., & Thompson, J. (2000). Being international: Student and teacher perceptions from international schools. Oxford Review of Education, 26, 107–123.

Hayden, M., & Thompson, J. (1998). International education: Perceptions of teachers in international schools. International Review of Education, 44, 549–568.

Hayden, M., & Thompson, J. (Eds.). (2011a). Taking the IB diploma programme forward. Woodbridge: John Catt Educational Ltd.

Hayden, M., & Thompson, J. (Eds.). (2011b). Taking the MYP forward. Woodbridge: John Catt Educational Ltd.

Hayden, M., & Thompson, J. (Eds.). (2012). Taking the IPC forward: Engaging with the international primary curriculum. Woodbridge: John Catt Educational Ltd.

Helsper, W., Krüger, H. H., Dreier, L., Keßler, C. I., Kreuz, S., & Niemann, M. (2016). International orientierte höhere Schulen in Deutschland. Zwei Varianten von Internationalität im Wechselspiel von Institution und Schülerbiografie. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 19, 705–725.

Hill, I. (2000). Internationally-minded schools. International Schools Journal, 10, 24–37.

Hornberg, S. (2010). Schule im Prozess der Internationalisierung von Bildung. Münster, New York, München, and Berlin: Waxmann.

Hornberg, S. (2012). Internationale Schulen. In H. Ullrich & S. Strunck (Eds.), Private Schulen in Deutschland (pp. 117–130). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Hornberg, S., & Pawicki, M. (2016). Transnationale Bildungsräume am Beispiel von IB World Schools. Paper presented at Deutsche Gesellschaft für Erziehungswissenschaft 25th Conference: Räume für Bildung. Räume der Bildung, 13–16 March 2016, University of Kassel, Kassel, Germany.

Howard, A., Polimeno, A., & Wheeler, B. (2014). Negotiating privilege and identity in educational contexts. New York: Routledge.

International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO). (2015). Become an IB world school. Retrieved July 27, 2015, from http://www.ibo.org/en/become-an-ib-school/

Kanan, H. M., & Baker, A. M. (2006). Influence of international schools on the perception of local students in individual and collective identities, career aspirations and choice of university. Journal of Research in international Education, 5, 251–266.

Keßler, C. (2016). Migrationsgeschichten, Anwahlmotive und Distinktionsprozesse von Schülerinnen und Schülern einer Internationalen Schule – Herausforderungen einer wissenschaftlichen Annäherung. In H. H. Krüger, C. Keßler, & D. Winter (Eds.), Bildungskarrieren von Jugendlichen und Peers an exklusiven Schulen (pp. 167–189). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Keßler, C., Krüger, H. H., Schippling, A., & Otto, A. (2015). Envisioning world citizens? Self-presentations of an international school in Germany and related orientations of its pupils. Journal of Research in International Education, 14, 114–126.

Koh, A. (2014). Doing class analysis in Singapore’s elite education: Unravelling the smokescreen of ‘meritocratic talk’. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 12, 196–210.

Köhler, S. M. (2012). Freunde, Feinde oder Klassenteam? Empirische Rekonstruktionen von Peerbeziehungen an globalen Schulen. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Krüger, H. H., Keßler, C. I., & Schippling, A. (2016). Shaping privileged perspectives? World citizenship and transnational biographies in the context of international education at an exclusive school. Paper presented at: 2016 European Conference on Education: Education and Social Justice: Democratising Education, 29 June–03 July 2016, Brighton, UK.

Masschelein, J., Simons, M., Bröckling, U., & Pongratz, L. (Eds.). (2007). The learning society from the perspective of governmentality. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Maxwell, C., & Aggleton, P. (2010). The bubble of privilege. Young, privately educated women talk about social class. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 31, 3–15.

Maxwell, C., & Aggleton, P. (Eds.). (2013). Privilege, agency and affect. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mehan, H., Villanueva, I., Hubbard, L., & Lintz, A. (1996). Constructing school success. The consequences of untracking low achieving students. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Murphy, E. (2000). Questions for the new millennium. International Schools Journal, 11, 5–10.

Nohl, A. M., Schittenhelm, K., Schmidtke, O., & Weiß, A. (Eds.). (2009). Kulturelles Kapital in der Migration. Hochqualifizierte Einwanderinnen und Einwanderer auf dem Arbeitsmarkt. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Phillips, J. (2002). The third way. Lessons from international education. Journal of Research in International Education, 1, 159–181.

Reay, D. (2004). It’s all becoming habitus: Beyond the habitual use of habitus in educational research. British Journal of Sociology and Education, 25, 431–444.

Reckwitz, A. (2004). Die Kontingenzperspektive der ‘Kultur’. In F. Jaeger & J. Rüsen (Eds.), Handbuch der Kulturwissenschaften. Band 3: Themen und Tendenzen (pp. 1–20). Stuttgart and Weimar: Klett.

Resnik, J. (2012). Sociology of international education. An emerging field of research. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 22, 291–310.

Song, J. J. (2013). For whom the bell tolls: Globalisation, social class and South Korea’s international schools. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 11, 136–159.

Ullrich, H. (2014). Exzellenz und Elitebildung in Gymnasien: Traditionen und Innovationen. In H. H. Krüger & W. Helsper (Eds.), Elite und Exzellenz im Bildungssystem. Nationale und internationale Perspektiven (Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft special issue 19) (pp. 181–202). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Zymek, B. (2015). Kontexte und Profile privater Schulen. Internationaler Vergleich lokaler Angebotsstrukturen. In M. Kraul (Ed.), Private Schulen (pp. 79–98). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Keßler, C.I., Krüger, HH. (2018). “Being International”: Institutional Claims and Student Perspectives at an Exclusive International School. In: Maxwell, C., Deppe, U., Krüger, HH., Helsper, W. (eds) Elite Education and Internationalisation. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59966-3_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59966-3_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-59965-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-59966-3

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)

text

text