Abstract

As Germany is considered the most powerful economy in the European Union, one would not expect food insecurity to be a German problem. However, rising social inequality means that food insecurity is an increasingly serious problem in the Global North and in otherwise stable European economies. The predominant responses to food insecurity on the part of the German political and social welfare systems can be characterized by delegation and denial of the problem and by a tendency to stigmatize the poor. Food surveys conducted in Germany exclude from their focus key at-risk groups and suggest that unsatisfactory nutrition is merely a self-inflicted problem caused by unhealthy eating patterns. However, a differentiated look at the data points to a more problematic constellation for Germany. For example, in Germany, 46.6% cannot afford a drink or meal with others at least once a month—a very high percentage compared to the rates of the EU27 (28.8%), Greece (18.5%), and the UK (18.2%). Food insecurity could be an intermittent reality for some 7% of Germany’s population. The number of food banks in Germany increased from 480 in 2005 to 916 in 2013, and 60,000 volunteers currently serve food to 1.5 million so-called ‘regular customers’. These numbers alone could be interpreted as evidence of food insecurity in Germany. Understanding individual day-to-day coping strategies of at-risk population groups will help with the development of social policy strategies to minimize food insecurity not only in Germany but also throughout Europe—provided policy-makers care sufficiently about this issue.

This article was made possible by the research framework of the third ‘Reporting on Socioeconomic Development in Germany—soeb’ (www.soeb.de/en/), funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Food insecurity

- Food poverty

- Nutritional poverty

- Germany

- Low-income household

- Necessities of life

- Nutritional consumption patterns

- Food bank

1 Food Insecurity in Germany?

The EU crisis that started in 2007 and still seems to be ongoing is complex and multidimensional, involving a banking crisis, a sovereign debt crisis and a macroeconomic crisis [16]. As Germany is considered the most powerful economy in the European Union and the assumed winner of the crisis [6], one would not expect food insecurity to be a German problem. Beyond the complexity of the crisis and the German ability to cope with it, however, public discourse has it that the most severe economic effects of the crisis hit not only fragile national economies but also low-income households all over Europe. And while German GDP per capita has been growing faster than in the EU-15 on average (ibid: 348), income inequality has risen sharply since 2000

[9]. The German Gini Coefficient (disposable income, post taxes and transfers) made a considerable jump between 1999 (0.259) and its all-time high of 0.297 in 2005, before retreating back somewhat to 0.286 in 2010. Thus the German Gini is better than UK value (0.341 in 2010); current German inequality levels, which were similar to those found in some Nordic countries in the 1980s, are very close to the OECD average (ibid).

Unlike rising inequality, in Germany food insecurity seems to be far less of a societal topic than in the UK, which could partly be the result of a more drastic reality that is hard to ignore, considering the 54% increase in food banks in the UK from 2012 to 2013 alone [2]. While Church and welfare organizations are highlighting the problem in the UK [18] and the press is reacting (for example, The Guardian started a Food Poverty news section in 2011, and has published more than 180 posts on the topic since then), in Germany food poverty has not yet had the same impact on public discourse, despite the Food Bank monitoring study receiving increasing recognition.

Food poverty in what we consider affluent societies seems to be a contradiction in terms. However, hunger has always been caused by poverty and inequality, not scarcity [5: 595]. With rising inequality, food insecurity—meaning the “inability to acquire or eat an adequate quality or sufficient quantity of food in socially acceptable ways (or the uncertainty of being able to do so)” [3]—is an increasingly serious problem in the Global North and in otherwise stable European economies. Food poverty in the heart of Europe is not an inevitable and short-term consequence of the last economic crisis, but follows certain changes to the social security system, particularly a more punitive sanctions regime [2]. In Germany and the UK alike, the state widely ignores the issue, delegating it to charitable solutions [1, 15]; individual coping strategies at the household level are therefore inevitable.

2 State of the Art: Food Insecurity and Poverty in Germany

On the basis of a range of evidence drawn from different sources of quantitative data, in 2011 we tried to prove that there is nutritional poverty in Germany, and in particular that social welfare recipients are widely excluded from eating out [11]. Since then, the situation has intensified. Physiological hunger and hunger for social inclusion by eating out are a reality in contemporary German society. And still, the predominant responses of the German political and social welfare systems can be characterized by delegation and denial of the problem and by a tendency to stigmatize the poor. We now provide some basic information on the state of food-related research in Germany.

As in 2011, we again face the situation of scientific and public obliviousness to the reality of food insecurity in Germany. According to the German food survey (Nationale Verzehrstudie [NVS]), one in five people are classified as obese, and excess weight is unequally distributed along the social scale [7]. However, this study was only carried out twice: first in the 1980s (NVS I) and a second time between 2005 and 2007 (NVS II). The scientific and public debate on eating patterns in Germany is dominated by obesity rather than food poverty. Whereas surveys on nutrition in Great Britain (National Food Survey, NFS) do take poorer population strata into consideration, or even over-represent them, the German NVS excluded population groups at a higher risk of nutritional poverty from the study. For example, migrants, homeless people or elderly people are underrepresented [11]. The importance of integrating these groups is indicated, as including these population groups permits more detailed insights into risks of nutritional poverty such as food availability, utilization and accessibility [17]. The German food surveys distort food insecurity because of these missing but particularly affected population groups and therefore implicitly indicate that unsatisfactory nutrition in Germany is merely a self-inflicted problem caused by unhealthy eating patterns such as excessive consumption of alcohol, fat, sugar and nicotine [7]. While nutritional poverty in the UK is discussed in the light of food security, and therefore the focus lies on relevant structures, food availability, food accessibility, subjective utilization and general conditions [11], food surveys in Germany are as granular in nutritional details as they are biased according to social stratification effects.

Despite the lack of thorough food-related research in Germany, there are some indicators that point to the rising problem of food insecurity in Germany. One indicator for deciding whether we face food insecurity in Germany is the few items that point to nutrition-related topics in surveys regularly conducted by the Federal Statistical Office. In 2011, [11, 12] based on SOEPFootnote 1 we estimated that 1% of the population or 800,000 people in Germany were spending less than EUR 99 per month of their household expenditures on food, and were likely to live in nutritional poverty and experience hunger at least from time to time. This may also hold true for an estimated 300,000 homeless people. As we also pointed out in 2011, food insecurity could be an intermittent reality for some of the 7% of the population—more than 5 million people—who have a monthly nutritional spend of EUR 100–199. Again based on the SOEP dataset, spending on food evidently differs according to employment: In 2011 German employed households spent EUR 362 a month on food, beverages and tobacco (13.7% of monthly private consumption expenditures) while unemployed households were only able to spend EUR 205 or 19.2% of their consumption expenses. The differences are much more evident if one compares expenditures for hotels and restaurants—for German employed households spent EUR 147 per month (5.6% of consumption spending), while unemployed households’ equivalent expenses total a meager EUR 21 a month, or 2% of their overall expenditure [15].

Unfortunately we do not have a research project in Germany that could be compared to the Poverty and Social Exclusion in the UK Project, which is based on the ‘necessities of life’ approach, aiming for a consensual measure of relative poverty, using the majority opinion to determine the set of items and activities which are regarded as necessities [4]. However, as there were no significant distinctions to be found between Scotland and the rest of the UK (ibid), we assume German public opinion to be similar regarding what is seen as necessary, and to what extent. The analysis for the UK contains several items that refer to nutrition and food consumption in a narrower sense. As such, 91% see two meals a day as necessary for adults, and 93% consider three meals a day essential for children. Fresh fruit and vegetables every day are seen as a necessity of life for adults by 83% and for children by 96%. And while meat, fish or an equivalent every other day are considered necessary for adults by 76% and for children by 90%, a roast joint or equivalent is only seen as indispensable for adults by 36% (ibid: 328–329).

As nutrition and food security are considered essentials of life, we will now look into some data on both nutritional and social aspects by comparing consumption data from the SILC/Eurostat survey for Germany, the EU27, the UK and Greece. We choose to compare Germany’s figures with those from the UK and Greece, because Germany and Greece are at opposite ends of the European scale for almost all social and economic indicators, while the UK is mostly found somewhere in the middle. For example, the 2012 unemployment rate in Greece is the worst in Europe at 24.5%, Germany’s was the best with 5.5%, while the UK lay in between with 8.1% (see [10]). This is also true for the share of “yes” responses to the question “Have there been times in the past 12 months when you did not have enough money to buy food that you or your family needed?” For Greece, the number jumped from under 10% in 2006–07 to around 18% in 2012, while there was a considerable decline in Germany from around 7% to under 5% and a moderate decline from 10% to around 8% in the UK (ibid: 28).

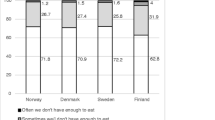

The data only shed light on nutritional behavior in terms of the ability to afford one meal with meat, chicken or fish (or a vegetarian equivalent) every other day (or at least once a day for children). Data (see Fig. 7.1) compared for the EU27, Germany, UK and Greece show a moderate decline in the percentage of the total population; for Germany the amount who could not afford the stated meal every other day dropped from 11% in 2005 to 8.2% in 2012. At first sight, nutritional poverty seems not to be an increasing problem—that is, if German public and political opinion take 8.2% as an acceptable figure—especially as the UK, Greece and EU27 show far higher percentages and instead faced a skyrocketing increase from 2011 to 2012 alone.

Data by SILC/Eurostat 2013; graphics by authors. For original graphics and data see [12], reprinted with permission by Cambridge University Press

However, a differentiated look at the data points to a more problematic constellation for Germany. Figure 7.2 shows that 27% of Germans with an income below 60% of the Medium Equivalized Income (MEI) cannot afford one proper meal every other day—a figure that is without question considerably better than Greece’s 42.2%, but higher than the European average of 23.5% and way higher than UK’s 11.4%. Even the percentage that cannot afford a proper meal although their income is above 60% of MEI is higher at 5.4% in Germany than in the UK, where 3.6% of the non-poor cannot afford a square meal every other day. Even if they cannot afford one for the adults every now and then, poor households evidently try hard to provide a substantial meal at least once a day for their children, as indicated by the overall lower percentages on the right side of Fig. 7.2 for the answer “cannot afford”. Germany, with 14% (below 60% of MEI) and 3.7% (above 60% of MEI) respectively, shows higher rates than those in the EU27 (12.9%), and considerably higher ones than the UK’s 2.4%, but Germany almost catches up with the 15.8% of crisis-stricken Greece.

Data for 2011 by SILC/Eurostat; Percentage for below/above Medium Equivalised Income; graphics by authors. For original graphics and data see [12], reprinted with permission by Cambridge University Press

The aforementioned PSE study [4] also asked about nutrition-related necessities of life that point more to the social core of food consumption and to food-related activities supporting social inclusion. Most of these activities were only explored with reference to adults: to dine out once a month is seen as essential by 25%, going out socially once a fortnight by 34%, and going out for a drink once a fortnight by 17%. Two more items were investigated for adults and children alike: 80% consider celebrations on special occasions as essential for adults and 91% for children; having friends or family round once a month is seen as a necessity for adults by 46%, and 49% see having friends round once a fortnight as essential for kids (ibid: 328–329).

As we previously highlighted [11], being able to afford meals at home is just one side of nutritional poverty. What we have coined alimentary participation (ibid)—experiencing the social function of food in public and together with others—has become crucial in a modern and individualized consumer society. We do not learn anything about eating out occasions in the SILC/Eurostat dataset. However, there are some hints, as there is one question aimed at how many can or cannot afford a get-together with friends or family for a drink/meal at least once a month (or for children: invitations to play and eat with friends from time to time).

Again, Fig. 7.3 shows alarmingly high percentages for Germany, especially for those with an income that falls below 60% of MEI: in Germany, 46.6% cannot afford a drink or meal with others at least once a month—a very high percentage compared to the rates of the EU27 (28.8%), Greece (18.5), and the UK (18.2%). Even for the population with an income above 60% of MEI, Germany shows higher percentages of people who cannot afford to drink and/or eat in company. Despite the cultural differences surrounding the social importance of shared meals or drinking in company all over Europe, and the fact that Germany might be less sociable in this respect, the explicit distance between Germany and the reference countries within the population below 60% of MEI hints at substantial problems of inequality in Germany, not mere cultural distinctions. The percentage that cannot afford children’s invitations is considerably lower than for adults and in Germany lower than the EU27 average (16.8%) and the 19.1% of Greece, but with 8.7% below and 1.7% above 60% of MEI the percentages in Germany are higher than in the UK (5.8 and 0.7%).

Data for 2011 by SILC/Eurostat; Percentage for below/above Medium Equivalised Income; graphics by authors. For original graphics and data see [12], reprinted with permission by Cambridge University Press

These actual figures—superficial as they are compared to the social complexities of nutritional patterns, poverty consumption and alimentary participation, and despite the relative success of Germany’s economy in coping with the crisis—again prove what we shed light on in 2011 (Pfeiffer et al.): There are people in our midst who are experiencing occasional hunger and are stricken by food insecurity. As delegation, denial, and stigmatization are still the predominant societal strategies for tackling food insecurity in Germany, the affected individuals are required to find their own solutions in their daily lives. The next section will offer a qualitative insight into this side of the problem.

3 Consequences: Coping with Nutritional Scarcity

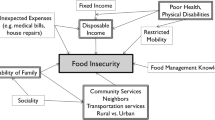

In the underlying qualitative longitudinal study [11], a socio-economic well-balanced sample of initially 106 welfare recipients as defined by Social Code II were repeatedly interviewed over a period of five years, using biographical in-depth interviews [14]. The transcribed material consists of 453 qualitative interviews, of which 81 cases were interviewed over all four waves. The analysis followed the methodology of qualitative content analyses [8], identifying a variety of interacting conditions that shape the ways in which the interviewees are coping with restricted nutritional situations: “objective” factors such as accessibility of food banks and other infrastructural features of food supply, facilities for food storing and cooking; “subjective” factors such as the overall attitude to food and eating, e.g. lifestyle, indulgence or modest eating, eating culture and health awareness, shopping patterns and use of food banks, capabilities of household and money management including cooking skills; “medical” factors e.g. illnesses that require special diets; and finally factors of “sociality”, such as caring for others or being cared for, the range and intensity of family and social networks in general, and the time structure of eating.

The way these conditions are entwined with each other was further elaborated: In a dialectical and dynamic form of ongoing biographical transformation and sedimentation, they are both the reason for, and the result of, individual representations of coping types to be described along three analytical dimensions: nutrition and alimentary experiences; biographical acquisition of eating habits; and overall food-related capabilities. By following the introduced analytical steps, we identified a broad range of eight individual coping types:

-

Against the odds. People coping actively with the situation; pragmatic and not shameful use of food banks; making the best of it.

-

Children first. Subjective feeling of severe restriction of food supply, but trying hard to provide their own children with good and healthy food.

-

Abandonment of quantity or quality. Coping with financial restrictions for food by lowering the quality and/or quantity of food, even if accompanied by the fatalistic anticipation of serious risks caused by chronic diseases (e.g. diabetes).

-

Surfing the ups and downs. Due to different financial situations during the month, this type changes the nutrition and strategies of food supply, simulating normality in the beginning and spiraling downward over the course of the month.

-

Embracing nutrition for sense and structure. For this type, activities such as cooking, eating, and the management of food supplies provide not only practical solutions to the restricted nutritional situation but sense and time structure, too.

-

Enforcing networks. In order to maintain the food supply, this type depends on social networks: Parents, children and friends are visited to improve the nutritional situation.

-

Risky food financing. Enhancing the food supply in potentially risky ways such as exploiting their own body (e.g. blood donations) or illegal work.

4 Concepts and Way Forward

Denial and stigmatization of hunger and nutritional poverty in Germany are the predominant ways of dealing with food insecurity and poverty in German society and government. The third and actually unique concept in the domain of social policy is delegating the problem to food banks (mostly organized by the Bundesverband Deutsche Tafeln e.V.—German Federal Association of Food Bank Initiatives), founded 1993 and mushrooming throughout Germany ever since. Although Germany does not face an abrupt rise in food bank consumption like the UK [2], the increase has accelerated since 2005, the year the Social Code II was introduced, from 480 to 916 food banks in 2013.Footnote 2 Currently 60,000 volunteers serve food to 1.5 million so-called ‘regular customers’. These numbers alone could be interpreted as evidence for food insecurity in Germany, although the regional distribution of food banks does not always match the socio-economic distribution of demand (ibid). Without acknowledging food poverty as a topical and real problem in Germany and by simply delegating the problem from the realm of social policy to ‘sweet charity’ [13] with all its contradictions and immanent problems, there is currently no governmental concept for addressing food poverty in Germany.

5 Future Development

Denial, stigmatization and delegation of food poverty as an objective problem in Germany are closely interrelated and mutually reinforce each other. If they continue to prevail, they might contribute to an increase in nutritional poverty and hunger. Here, social sciences have a role to play in challenging the current orthodoxy. The best way to do so is to orient its methods and concepts to the realization that alimentary deprivation can also become an existential problem for many people in German society. As social transfers are more often part of consolidation plans reacting to the last crisis than other areas of public spending [10], and therefore spending cuts are more likely to hurt the poor (ibid: 53), food insecurity will remain a problem.

6 Conclusion

We have provided some current quantitative data on food insecurity in Germany and contrasted these with qualitative results on nutritional coping strategies. In conclusion, for all coping types one thing seems to hold true: As long as people have to rely on social benefits, they are very likely to suffer from rigid constraints concerning alimentary participation, amounting even to exclusion. Alimentary participation in modern consumer societies is a complex problem for the poor, and it leads to a daily experience of exclusion which no individual coping strategy can satisfactorily offset. The results collated shed a first light on nutritional consumption patterns in unemployed German households; we will extend our research into the complex interrelations between food choice and other aspects of poverty consumerism. Understanding individual day-to-day coping strategies will help with the development of social policy strategies to minimize food insecurity not only in Germany but also throughout Europe—provided policy-makers care sufficiently about this issue.

7 Summary: Key Messages

-

Rising social inequality means that food insecurity is an increasingly serious problem in the Global North, and Germany is no exception, despite its economic power.

-

The predominant responses to food insecurity on the part of the German political and social welfare systems can be characterized by delegation and denial of the problem and by a tendency to stigmatize the poor. Food surveys conducted in Germany exclude from their focus key at-risk groups and as a consequence suggest that unsatisfactory nutrition is merely a self-inflicted problem caused by unhealthy eating patterns.

-

A differentiated look at the data points to a more problematic constellation for Germany.

-

Food insecurity could be an intermittent reality for some 7% of the country’s population.

-

The number of food banks in Germany increased from 480 in 2005 to 916 in 2013, and 60,000 volunteers currently serve food to 1.5 million so-called ‘regular customers’.

-

Understanding individual day-to-day coping strategies will help with the development of social policy strategies to minimize food insecurity not only in Germany but also throughout Europe—provided policy-makers care sufficiently about this issue.

Notes

- 1.

German Socio-Economic Panel http://www.diw.de/soep.

- 2.

References

Caraher, M. and Dowler, E. (2014) “Food for Poorer People: Conventional and ‛Alternative’ Transgressions”, in: M. Goodman, and C. Sage (Eds.), Food Transgressions: Making Sense of Contemporary Food Politics. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 227–246.

Cooper, N., Purcell, S., and Jackson, R. (2014) Below the Breadline. The Relentless Rise of Food Poverty in Britain. Manchester, Oxford, Salisbury: Church Action on Poverty, Oxfam, Trussel Trust.

Dowler, E. and O’Connor, D. (2012) ‘Rights based approaches to addressing food poverty and food insecurity in Ireland and UK’. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 44–51.

Gannon, M. and Bailey, N. (2014) ‘Attitudes to the ‛Necessities of Life’: Would an Independent Scotland Set a Different Poverty Standard to the Rest of the UK?’, Social Policy and Society, 13, 321–336.

Holt-Gilménez, E., Shattuck, A., Altieri, M., Herren, H. and Gliessman, S. (2012) ‘We Already Grow Enough Food for 10 Billion People …and Still Can’t End Hunger’. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 36, 595–598.

Kaitila, V. (2014) ‘Transnational Income Convergence and National Income Disparity: Europe, 1960–2012’. Journal of Economic Integration, 29, 343–371.

Max Rubner-Institut (2008) Nationale Verzehrstudie II – Ergebnisbericht, Teil 2, Karlsruhe: Bundesforschungsinstitut für Ernährung und Lebensmittel.

Mayring, P. (2000). ‘Qualitative Content Analysis’. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2, Art. 20. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0002204.

OECD (2011). Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising. Country Note Germany. http://www.oecd.org/germany/49177659.pdf.

OECD (2014). Society at a Glance. OECD Social Indicators. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2014-en.

Pfeiffer, S., Ritter, T. and Hirseland, A. (2011) ‘Hunger and nutritional poverty in Germany: quantitative and qualitative empirical insights’, Critical Public Health, 1–12.

Pfeiffer, S., Ritter, T. and Oestreicher, E. (2015) ‘Food Insecurity in German households: Qualitative and Quantitative Data on Coping, Poverty Consumerism and Alimentary Participation’, Social Policy and Society: 1–13.

Poppendieck, J. (1999) Sweet Charity? Emergency Food and the End of Entitlementood insecurity in Ireland and UK. New York, London: Penguin House.

Rosenthal, G. (2004) ‘Biographical Research’, in C. Seale, G. Giampieto, J. F. Gubrium and D. Silverman (eds)., Qualitative Research Practice, London: Sage, 48–64.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2013). Datenreport 2013: Ein Sozialbericht für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Destatis: Wiesbaden.

Tosun, J.; Wetzel, A. and Zapryanova, G. (2014). ‘The EU in Crisis: Advancing the Debate’. Journal of European Integration, 36, 195–211.

Withbeck, L., Xiaojin, Ch. and Johnson, K. (2006). ‘Food insecurity among homeless and runaway adolescents’, Public Health Nutrition, 9, 47–52.

Webster, A. (2014). 999 Food. Emergency Food Aid in the Thames Valley. A Snapshot. Oxford: Department of Mission Church of England.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pfeiffer, S., Ritter, T., Oestreicher, E. (2017). Food Insecurity and Poverty in Germany. In: Biesalski, H., Drewnowski, A., Dwyer, J., Strain, J., Weber, P., Eggersdorfer, M. (eds) Sustainable Nutrition in a Changing World. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55942-1_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55942-1_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-55940-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-55942-1

eBook Packages: Chemistry and Materials ScienceChemistry and Material Science (R0)