Abstract

Although a genre approach to writing instruction has emerged as the most widely advocated pedagogy in second language (L2) writing instruction, little empirical research has examined its effects on Chinese as a Second Language (CSL) writing. The purpose of this study is thus to address this research gap by examining the effects of a Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) approach to genre instruction on the textual quality of CSL writing. This approach is taken as the instructional framework due to its emphasis on explicit awareness of language as learning to write. This pedagogical approach was implemented in two CSL courses at tertiary level and the primary data consist of 32 essays and 16 students’ responses to an evaluation questionnaire on this pedagogical approach. The quantitative analysis shows that writers of pre-intermediate level made statistically significant progress in terms of content, organization, word choice and grammar, as evident in the differences between the scores in the pre- and post-test essays. Most participants indicated positive response to the evaluation questionnaire with regard to the effectiveness of this approach in enhancing their Chinese writing competence. The findings suggest that instruction based on this approach may hold great potential for enhancing students’ genre awareness and subsequent writing quality.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In response to the growing demand for learning Chinese, Chinese as a Second/Foreign Language (CSL/CFL ) educators have identified a number of difficulties involved in CSL/CFL learning, and thus worked to find effective pedagogical approaches to enhance students’ proficiency in this regard. Part of these efforts have been devoted to exploring the acquisition of an isolated Chinese linguistic feature or unit (i.e. ‘NP-topic’ in Chen and Shi 1999; ‘perfective aspect’ in Duff and Li 2002; ‘classifiers’ in Kuo et al. 2011; ‘Mandarin tones’ in Wee 2007), and to identifying literacy-related issues, with a particular focus on word recognition and reading as well as radical awareness (i.e. Bassetti 2005; Chen et al. 2013; Shen and Ke 2007; Tsai et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2003). Despite the progress made in this area, little attention has been paid to the learning of CSL/CFL writing beyond the word level. Most CSL/CFL writing research is overwhelmingly focused on addressing the issue of learning how to write Chinese characters. Indeed, the lack of grapheme-phoneme correspondence (GPC) rules in Chinese orthography imposes considerable difficulties when learning Chinese characters and words. However, learning Chinese should go beyond character learning, so that students can achieve the effective communication that is required at an advanced literacy level. In other words, how to make meaning through effective manipulation of language resources is the ultimate goal of language learning, and thus requires more attention in a CSL context.

Most distinctly, L2 writing scholarship has shown that composing texts is considered beneficial for second/foreign language (L2) acquisition. Several researchers have highlighted the language learning potential involved in the practice of writing, because the act of composing itself can promote not only writing abilities but also L2 development across modalities (Byrnes 2013; Harklau 2002; Leki 2009; Manchón 2009, 2011a; Ortega 2012; Urquhart and Weir 1998; Williams 2012). This instrumental role of writing in L2 learning has been further substantiated in empirical findings, revealing how writing enables L2 knowledge internalization, restructuring and consolidation (see Williams 2012; Manchón 2011b, c, for a review of the related works). Undeniably, “second language acquisition may be triggered more through literacy activities than through oral interaction” (Weissberg 2008: 35). Nevertheless, the suggestive evidence that has been obtained about the facilitating role of writing in L2 acquisition has been primarily centered on learning English as a second/foreign language, and researchers have thus called for studies on other languages and in different instructional contexts in order to provide further insights about the instrumental role that writing can play in L2 educational settings.

Given the importance of writing in L2 acquisition and the urgency for effective communication in written language among Chinese learners, it is surprising to find out that there have been relatively few studies examining this communicative modality in CSL/CFL research. Therefore, the present study aims to address this research gap by introducing and investigating the feasibility of a genre-based approach, as informed by systemic functional linguistics , to CSL writing instruction.

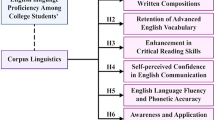

2 A Systemic-Functional Approach to Writing

A systemic-functional approach to writing as informed by M.A.K. Halliday’s Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) is a theoretical framework which conceptualizes a theory of language as a meaning-making system (Halliday 1994; Halliday and Matthiessen 2014; Martin 2009). It postulates a model of language on the basis of how languages make meaning in a wide variety of social and cultural contexts. This model of language attempts to explain how the meaning potential of this system is realized through three metafunctions (i.e. ideational, interpersonal and textual) that work simultaneously to co-construct meanings appropriate to the situated context. The ideational metafunction encodes our experience; the interpersonal metafunction establishes social relationships between language users and the target audience; and the textual function regulates the message flow to fit in the language event. Central to this theory of language are the dynamics between the three language functions and contexts. The latter can be further divided into the broader context of culture and the immediate context of the situation. In recent years the context of culture has been developed into the notion of genre (Troyan 2014), which is realized in the register variables in the immediate context of a situation (Martin 2009). Each of the register variables, field, tenor and mode corresponds to the three metafunctions of the language system: ideational, interpersonal and textual. This dynamic account is captured in Fig. 1.

SFL genre and its language metafunctions (Adapted from Martin 2009: 12, Reprinted with permission from Elsevier)

Dubbed as “an education-friendly theory of language” (Byrnes 2009: 3), an SFL-inspired approach to writing can “link the perspectives of learning to write and writing to learn under the overarching construct of genre…” (Byrnes 2013: 101), fulfilling the instrumental role writing can play in language and literacy education. That is, how we “mobilize language” (Martin 2009:13) to communicate when participating in diverse social activities. Martin defines genre as “a staged, goal-oriented social process(es)” (2009: 13). The term “staged” refers to the multiple phrases/processes involved in realizing a genre, while the term “goal-oriented” indicates that each genre intends to achieve a socially-oriented purpose. An SFL-based genre approach thus stresses the explicit instruction of the language resources affiliated with the rhetorical stages to enact the communicative purposes of a specific genre. By highlighting language as meaning-making resources, it accounts for how language functions in different contexts and attends to expanding language learners to function in a wide array of social activities.

This language-based approach to writing was initially advocated and applied in an Australian context, in which the rhetorical components along with their linguistic renditions were applied to realize a wide array of elementary genre types across the curriculum (e.g. recount, explanation, or procedure writing, see Macken-Horarik 2002, for an overview), and then developed for pedagogical purposes. The results of such work subsequently inspired educational linguists and language practitioners from all over the world. Among the related studies, the current review focuses on works applying this approach to second/foreign language writing instruction. In English as a L2 language setting, writing instruction informed by an SFL approach can effectively enhance the textual quality of the English narrative and argumentative texts written by primary school students (Polias and Dare 2006), as well as the narrative writing of (Cheng 2008) and summary writing of EFL college students (Yasuda 2015). Moreover, in learning to compose German as an L2 language, SFL -inspired instruction has also contributed to the complexity of L2 writing , as observed in thematic construction (Ryshina-Pankova 2006) and use of grammatical metaphors (Byrnes 2009; Ryshina-Pankova and Byrnes 2013; Ryshina-Pankova 2015). It also seems well-suited to other language contexts, as several studies revealed its success in various language programs such as Chinese literacy at the primary school level in Canada (Mohan and Huang 2002; Huang and Mohan 2009), university-level French writing (Caffarel 2006), early to advanced levels of a Japanese program (Teruya 2006, 2009), and heritage Spanish language learning at college-level (Achugar and Colombi 2008; Colombi 2002, 2009).

As noted above, SFL-inspired approaches to writing have been applied in various L2 education settings. However, its application to CSL writing instruction at the college level has remained largely untouched. The most important contribution of this paper is thus that it elaborates the implications and applications of this approach for the L2 writing field in general, and CSL writing in particular. Therefore, the present study draws on the SFL conceptualization of genre and has the following empirical questions to guide its examination of the pedagogical effects of an SFL-inspired approach on the development of CSL students’ writing. It is assumed that explicit instruction of these linguistic resources related to a specific genre can heighten CSL learners’ awareness of them, and thus enable the students to achieve a specific social action and consequently foster their communicative competence in Chinese writing. The two questions examined in this work are as follows:

-

1.

What are the effects of the genre instruction on the quality of students’ writing?

-

2.

What are students’ evaluations on the usefulness of this pedagogical intervention?

3 Method

This pedagogical intervention was part of a research project intended to develop a CSL multimedia writing program inspired by an SFL genre approach to writing. The current study aims to investigate its effects on the quality of student texts based on one lesson unit, and examine their evaluations of the learning materials in order to guide subsequent development of this program. This research thus utilized a quasi-experimental design with the same participants receiving pre-/posttest treatments. This treatment was not implemented in the participants’ regular Chinese classes, but in a pull-out short writing program lasting for 6 hours on two consecutive weekends, with roughly three hours each week. The participants were rewarded with a small stipend for their time and effort spent on this research.

3.1 Participants

Students enrolled in two CSL courses at a national university in Taiwan were invited to participate in this research. Initially there were 22 participants, but six of them failed to complete the whole research cycle and their data were not included in the final analysis. The 16 participants were mainly registered as post-graduate students at this university, and the majority of them were from South-East Asia, with alphabetic language backgrounds. Their ages ranged from 23 to 35, with a median of 26. All of them had learned Chinese in their home countries and had studied in Taiwan for more than one year. Their Chinese proficiency was categorized as pre-intermediate level, as indicated in the results of a simulated TOCFL (Test of Chinese as a Foreign Language) test, which is similar to the A2 or B1 level of the Common European Framework of Reference of Languages (CEFR). The participants were required to take a TOCFL test for course placement three months before this research project was undertaken.

The two CSL classes were instructed by two experienced Taiwanese CSL teachers, who are enthusiastic with regard to developing and incorporating multi-media materials in their classes. Based on the researcher’s observations in their classrooms, their instruction involved a high degree of interaction among teachers and students, and thus they were considered suitable candidates to implement the proposed teaching materials in their classrooms.

3.2 Instructional Approach

This pedagogical intervention applies one lesson unit from the multimedia Chinese writing program, which was designed on the basis of systemic functional linguistics . Each lesson unit comprises three sections: language resources, writing strategy, and assignment/assessment. For the language resources section, the ideational, interpersonal and textual features associated with the communicative purpose of the target genre were illustrated with multiple encounters of different texts and exercises. To ease the teacher’s burden of learning and applying SFL-based materials, a teacher’s manual was attached to each lesson unit specifying the purpose of each instructional activity and the recommended instructional strategies. The focal lesson in this research is about a descriptive genre , and the selected theme is related to food. The instructional procedure for the two meetings on consecutive weekends is detailed below, along with a description of the SFL -inspired teaching materials. This pedagogical intervention was undertaken in three stages, starting from building contextual awareness, to introducing the rhetorical stages of a descriptive genre and their associated linguistic repertoire, and finally presenting writing strategies that could help in effectively organizing these resources into cogent texts. All the instruction was conducted primarily in Chinese, except on rare occasions when students needed further clarifications, the teachers may offer explanation in English.

In the first meeting, the instruction started with fostering students’ awareness of the communicative purpose of the target genre. Students were orally asked with general questions related to the communicative purpose involved in the act of describing, such as “What’s the purpose of a descriptive text?” “Where can you find it?”, “How will you describe an experience or an object?” and so on. The students were then asked more specific questions related to the focal theme, food, such as “What’s your favorite Taiwanese food?” and “What type of food from your country do you miss very much?”. Teachers then pointed to the three rhetorical stages involved in descriptive genre , as follows: a general statement of the target food, a description of different aspects, such as sensory images, and related activities, such as when/where one will taste this food. This classification of genre stages related to a descriptive genre was based on the scheme specified in Macken-Horarik (2002). The goal of these activities is to raise the students’ contextual awareness by showcasing the communicative purpose and the constituent stages of the descriptive genre.

The instruction then proceeds to introduce the language resources involved in realizing the descriptive genre . To realize the rhetorical stages of this descriptive genre with a focus on the theme of food, the ideational resources consist of verbal processes of description and related activities, food taxonomy as well as sensory attributes. The interpersonal meanings include the expression of the writer’s stance toward the focal objects to purposefully activate the intended attitude in readers. As regards the textual function, the materials contain the pertinent demonstratives/pronouns as well as conjunctions to offer resources for developing greater cohesion and cohesiveness. These language functions and some exemplary linguistic instances are summarized below (Table 1).

Note that we do not intend to cover all possible linguistic resources, but only key words and sentence patterns that are associated with this theme and learnable at this proficiency level. In the instructional materials, these words/sentence patterns are first illustrated in an isolated manner in order to facilitate student’s recognition of the Chinese characters. However, several follow-up exercises engaged the students in analyzing various descriptive texts, so that they could relate the deployment of these word/sentence patterns to the purposes of the descriptive genre . Some sample instructional materials are given in Appendix A, along with their English translations.

During the first meeting, the instruction on language renditions only covered ideational and interpersonal resources, and the second meeting started with coaching the participants in the use of textual resources and proceeded to direct students to effectively incorporate them into a meaningful text. The teacher followed the writing strategy sections of this multimedia program to co-construct a text with the students, using the exemplary topic of Thai spicy soup. When brainstorming the different aspects of this food together and voicing their ideas, the students were guided through the brainstorming strategies listed in the materials, such as “What does this food consist of?” “How does this food taste like?” “When do you want to taste this food?” “Where do you go to try it?” “How do you feel after eating it?”. All these questions are associated with the genre stages to realize its communicative purpose. Different organization patterns were then provided to the students, but they were advised to apply these schemes in a flexible way. Along with the teachers, the students co-constructed a text in response to the prompt of Thai-style spicy soup before they were required to compose their post-test texts independently.

Since SFL -based educational practices are not popular among CSL instructors in Taiwan, preliminary training was required to facilitate the understanding of the two participating instructors about the teaching materials based on SFL’s conceptualization of genre. Both instructors were thus engaged in intensive training about the principles of this functional approach to writing (as shown in the literature review), the distinct features of SFL-inspired teaching materials (as noted above), and the instructional procedures and activities to be implemented in the current research. After the tutorial, they were asked to preview the focal instructional materials in this multimedia writing program and the teacher’s manual prior to the pedagogical implementation, and extensive discussions between the researcher and instructors were held to solve any ensuing problems or questions regarding the use of these materials.

3.3 Instruments

To answer the first research question, two instruments were developed to investigate the effects of this approach on students’ writing quality: writing tasks and writing assessment scheme. Three Chinese writing topics (see Appendix B for example) related to the theme of food were offered to the participants for the pre-/post-tests. Topic A asks students to describe their favorite Taiwanese food and say what is distinct about it with regard to features such as color, smell, flavor, ingredients, recipes, and so on. The instructions for Topics B and C are the same, but the theme for Topic B is the students’ favorite international food, while Topic C is related to any strange food they have tasted.

Appendix C shows the assessment scheme used to score the pre-and post-test essays in terms of the textual quality. This is partially adapted from the six-point Chinese writing scoring rubric for middle school students stipulated by Taiwan’s Ministry of Education, and is revised based on the typical discourse features of descriptive genre . It is composed of four dimensions: content, organization, language use and grammar. The content dimension is defined as the degree to which the writer’s elaboration of the topic , and inclusion of interesting, rich and related details, such as the presentation of sensory images, a wide range of food taxonomy and related activities. The organization dimension refers to the structure of the text, with a clear introduction, body and conclusion, as well as the connections between ideas. The language use dimension is defined as the range of verbs, appraisal expressions, and use of specific vocabulary appropriate to the experience being described. The grammar dimension includes syntactic appropriateness, diversity and complexity. Note that these dimensions are not intended to specifically evaluate each respective language resource taught. Instead, it is argued that each language resource contributes to the construction of different assessment dimensions. Ideational and interpersonal resources are mainly related to the dimensions of content development and language choice, while textual resources are mostly associated with organization and grammar. The scores were derived impressionistically along a scale of “not evident”, “ minimum evidence of mastery”, “some evidence of mastery”, “adequate evidence of mastery”, “outstanding evidence of mastery”, and “strong evidence of mastery”, ranging from 1 to 6.

To answer the second research question about the usefulness of the SFL -inspired materials, an evaluation survey was piloted, refined, and administered by the researcher and class instructors. This questionnaire comprises one open-ended question and 19 close-ended questions, which are composed of four parts: their evaluation on the learning of ideational, interpersonal, textual materials and writing strategies and their usefulness in composing this descriptive genre . All items were queried using 4-point ranking scales, ranging from “strongly agree”, “agree”, “disagree” and “strongly disagree”. The open-ended question inquires their suggestions and comments on this multimedia writing program and the instructional the approach beyond what has been stated in the close-ended questions. Students’ demographic information with regard to their age, gender and nationality were also collected. Participants were presented with a bilingual questionnaire format to prevent any misunderstanding of the items and ensuing biased data.

3.4 Data Collection and Analysis

The primary data consisted of 32 essays and 16 students’ responses to an evaluation questionnaire on this instructional approach. The first set of data is composed of the pre-/post-test essays, which were written before and after the two-week period of the experimental treatment. Participants were asked to compose their pre-/post-tests in response to the same topic . It should be noted that they were not informed about their post-test topics and their post-test essays were written in class without access to their pre-test works. When the participants composed each text in a computer lab for half an hour or one hour, they were allowed to access any on-line materials, including this writing program, on-line dictionary or any other internet resources. Another data set was comprised of students’ evaluation questionnaires (see Table 4 in the Results section). All participants were asked to fill in this questionnaire once they had completed their post-test essays.

With regard to data analysis, each essay was graded by the researcher using the above six-point assessment scheme. This analysis was validated through inter-rater analysis, which involved the two instructors analyzing half of the data, with each instructor receiving a randomly selected part of the whole. Both instructors received a standardized training procedure to help them achieve this, and each needed to score two sample essays with the researcher using the assessment scheme. If an essay received two scores differing by more than one point for each scale, the disagreement was resolved through a thorough discussion between the researcher and instructor. After the training sessions, the two raters scored 16 texts in individual sessions. To calculate the inter-rater reliability, the Pearson’s correlation coefficients were run to examine whether the assessment criteria used by the three raters for the 16 texts were consistent and reliable. The inter-rater correlation coefficients among the researcher and the two instructors ranged from 0.85 to 0.98 for the four writing dimensions, indicating that the three raters reached a consensus on the assessment of textual quality. Paired-samples t-tests were then undertaken to examine the pre-/post-test essays with regard to each dimension listed in the assessment scheme. On the questionnaire, percentages were determined for all close-ended questions and descriptive statistics were adopted to analyze students’ perceptions of this pedagogical intervention.

4 Results

4.1 Effects on Writing Quality

The relative effectiveness of the proposed approach is reported here, though no hard conclusions regarding the development of CSL writing can be drawn because of the sample size and the specific genre taught. As shown in Table 2, the results of the paired-samples t-test illustrated that students made statistically significant progress in all writing features based on the assessment scheme, as evident in the difference between the scores in the pre- & post-test essays.

With respect to the quality of content, scores for the post-test essays were significantly higher than those for the pre-test essays, t(15) = 5.84, p = .000. This indicates that although the pre-test writing texts addressed the subject, they were not developed with vivid and interesting details with regard to the different aspects of the target food and relevant activities involved in tasting it. The more concrete details, sensory images and emotional responses offered in the post-test texts supported the descriptions, although adding even more specific information would have improved the quality of the texts. Likewise, the students’ scores on the organization dimension for the post-test essays were significantly higher than those for the pre-test essays, t(15) = 5.37, p = .000. The structure of the pretest essays was generally clear, but the wrong spelling or inaccurate use of certain phrases or lack of transitions often distracted the readers. While the learners’ post-test samples were better organized, with apparent and appropriate deployment of transitions, some lapses were still found. In terms of vocabulary usage, the scores for the post-test essays were significantly higher than those for the pre-test essays, t(15) = 7.32, p = .000. Their language is rather basic, with limited word choice, in the pre-test essays, but more descriptive words/phrases were effectively presented in the post-test writing, suggesting the learners’ progression towards more mature language use. Similarly, their scores on grammar usage for the post-test essays were significantly higher than those for the pre-test essays, t(15) = 4.39, p = .001. Obviously, several problems or errors with sentence structure, such as run-on sentences or sentence fragments, appear in the pre-test essays. However, most sentences are better constructed in the post-test texts, though simple sentences are still used repeatedly and some errors remain.

It seems that improvement in the quality of the learners’ post-test writing correlates strongly with their heightened awareness of the discourse features associated with the taught genre. The scaffolding with regard to the rhetorical stages and the relevant linguistic resources of a descriptive genre enhanced the participants’ ability to construct more extended messages. The instruction has been an enabling tool in their writing since it broadened their understanding of what should be included in this genre, and thus guided them to search for their intended meanings from online resources in order to effectively convey their message. Generally speaking, the students’ performance on the pre-test was relatively under-developed for all the features examined in this work. Except for grammar, their average scores were all below three on a scale of six for the three remaining traits. This indicates that most of the learners failed to elaborate the content, organize their ideas in a clear manner and express their ideas effectively via appropriate vocabulary and syntactic expressions. After the intervention, they expanded their textual repertoire and showed greater control of these features. As shown in the gain scores, the students made the most progress on content, organization and vocabulary usage, but the least progress on grammar. It is plausible that as students add more supporting information to the texts, they may utilize more varieties of sentence structures, some of which may not be successful attempts. This may explain why their progress with grammar was less significant than that seen with the other writing features.

4.2 Textual Analysis of One Set of Writing Samples

For these CSL students, scaffolding the language resources associated with a genre improved the quality of their descriptive writing in a relatively short period of time, just two weeks. To exemplify to what extent the participants improved their writing in terms of several genre features after this treatment, one set of pre- and post-test texts was analyzed in terms of the genre stages and three language resources. This set of writing samples were chosen since it represents the average gains between the pre-test and post-test among the participants. The examples, showing gains of 1-2 points on all writing features listed in the assessment scheme, illuminate the average gain from 0.75 in the pre-test to 1.38 in the post-test with respect to the focal writing features. This set of essays was written by Mohammad (pseudonym) responding to topic A about one’s favorite Taiwanese food. His Chinese texts shown below are also reproduced with pinyin transcriptions. The English translation (see Appendix D) of the Chinese essays is semantically based in order for non-Chinese readers to catch the meanings elicited in the Chinese texts and thus all the grammatical errors in the original ones were removed. Figure 2 below illustrates the genre stages manifested in the participant’s pre-/post-test writing.

As can be seen, the post-test work was more elaborated, not only with richer supporting details in each rhetorical stage, but also with inclusion of more genre stages. His pre-test response was restricted to a general statement of his favorite food but failed to offer any description of its various aspects or associated activities or functions. After the instructional scaffolding, his post-test work was better constructed, with two more rhetorical stages that offered the ingredients of the selected food, sensory details and related activities.

This student’s use of different language resources to realize these generic stages can further illuminate his progress made after the pedagogical intervention. Table 3 shows the shift from pre-test to post-test essays with regard to the prominent language features associated with the descriptive genre .

As can be observed in the post-test writing, Mohammad made noticeable efforts to build up the extended meanings by adding more verbal descriptions, such as, with the use of kàn qǐ lái 看起來 look like or wén qǐ lái 聞起來 smell like, increasing the variety of related activities, such as, qù huǒ chē zhàn fù jìn de yì jiā fàn guǎn chī 去火車站附近的一家飯館吃 go to a restaurant around the train station to taste, or shì kàn 試試看 try, expanding food taxonomy, such as, cái liào 材料 ingredients, jiàng yóu 醬油 soy sauce, liào lǐ 料理 cuisine, as well as varying their conjunctions, for instance, suī rán…dàn shì 雖然 但是 although…but, suǒ yǐ 所以 therefore. Most distinctively, Mohammad failed to present any sensory images in the pre-test but incorporated vivid descriptions to capture reader’s attention in the post-test work, such as, hěn hǎo chī 很好吃 delicious, hěn xiāng 很香 sweet-smelling. He was also more capable of enacting interpersonal relations by incorporating more evaluative comments in the post-test writing, for instance, hěn jiǎn dān 很簡單 very easy or hěn yǒu míng 很有名 well-known. These noteworthy improvements, as manifested in their post-test works, suggest the students’ developmental growth in constructing more elaborated messages with smoother connections and more personal comments, and thus demonstrates proficient capability in making meanings appropriate to the conventions of the target genre.

4.3 Students’ Evaluation of This Approach

As noted, the present study is the first attempt to apply an SFL approach to CSL writing instruction at tertiary level, and the major purpose of this research is to understand its pedagogical effects on learners’ development of writing proficiency for developing a CSL multi-media writing program. The participants’ perceptions of its advantages and disadvantages in scaffolding their writing can provide further insights into the design of this program, and thus help to maximize its learning potential. As shown in Table 4, in response to items 1–6, 8–9, 11–14, 16 and 18, dealing with the students’ learning of these different language resources, the overwhelming majority of the participants felt that the instructional materials helped them to acquire the focal language features and writing strategies. As regards items 7, 10, 15, 17 and 19, which asked about the effectiveness of these resources or strategies in sharpening the students’ writing performance, over 80% of them either strongly agreed or agreed that this approach was effective in achieving the intended goals, with only three respondents (19%) feeling otherwise.

The students’ responses to open-ended question 20, requesting any other suggestions or comments on the materials, may help explain the above findings. These comments can be grouped into two major problems related to the design of the instructional materials and implementation procedures, as follows: (1) the lack of ‘pinyin ’ in all the instructional materials imposed difficulties on learning and subsequent application of these new language features; (2) the students were not able to absorb so many new items in such a short time span. The first reason is more associated with the design of the instructional materials, and are actually not related to the SFL theory and application. Given that most of the participants were placed at the pre-intermediate level and Chinese is their second foreign language, we assumed that students should be able to grapple with Chinese texts in the absence of pinyin. However, as half of the participants mentioned the importance of pinyin in facilitating their learning, this comment is applied in follow-up revision and development of this on-line CSL writing program. One updated example of the instructional materials is shown in Appendix A (Example 2) and one slide of the old version in Example 1. The second problem was related to the first one, since without the scaffolding of pinyin , the students may find it somewhat intimidating to learn the new language features and apply what they have been taught to their own writing within a two-week time span. It may also partially elucidate why the skeptical attitudes observed in some participants’ evaluation centers on the application of these resources to their writing. A small number of participants, particularly the less-proficient learners, were not able to directly apply the focal linguistic exponents in their writing, and this may have caused them to feel more negative about the value of the pedagogical materials. The other possible factor accounting for this problem is that there is a wealth of food items to be selected as the students’ writing theme, and it is impossible to cover all relevant language resources in the teaching materials. Another factor contributing to this problem is there were several mini-exercises and activities in each subsection of the language resources and writing strategy, and the students may have encountered unfamiliar words in these and thus felt over-whelmed. Implementation of this program in regular Chinese courses with sufficient time to complete the in-class and after-class activities would prevent this problem, and may provide a more comprehensive profile of the effectiveness of this program. However, time constraints and scheduling worked against this method in the current study. The purpose of this research was to evaluate this approach based on only one lesson unit prior to the subsequent development of a complete multi-media CSL writing program. As such, the implementation needed to include a lot of materials and activities for the focal lesson unit in order to provide a comprehensive view of the students’ strengths and weaknesses. Unfortunately, many instructors of regular CSL courses were not keen on taking up this research in their classes, because it did not fit in with their scheduled lessons, and the implementation would require too many class hours.

Despite these drawbacks, the questionnaire data obtained in this work show that most participants felt that these instructional materials, as developed based on the concept of an SFL genre approach, could improve their writing competence. This finding complements the results of the textual analysis and gain scores from the students’ pre-tests to their post-tests, demonstrating that explicit instruction in the language and discourse features related to a genre was able to enhance their awareness of the target features and improve the textual quality of their writing. Stated in another way, the results of this study show that the students moved along a continuum of literacy development that enhanced their generic mastery, an ability that counts as one of the key characteristics of advanced literacy (Colombi 2009).

5 Discussion

The results of this study on the quality of students’ pre-/post-test writings and their responses to the questionnaire reveal that the proposed SFL -inspired approach holds great potential for supporting students’ meaning making in one educational setting. The CSL participants, as both writers and language learners, expanded their Chinese writing abilities, as observed in their genre awareness and lexicogrammatical choices to realize the genre. Interestingly, scaffolding the ideational, interpersonal and textual resources appeared to push students to explore the relevant expressions in these dimensions beyond what was included in the instructional materials, as they responded to the writing promot that present textual challenges for these L2 learners. It suggests their change in genre knowledge affected their subsequent language choices. This research thus corroborates the findings of other studies that demonstrate making salient connections between the meaning and language forms associated with a specific genre can foster students’ writing development across languages, literacy levels and genre types (Byrnes 2009, 2013; Cheng 2008; Gebhard et al. 2014; Harman 2013; Liardét 2013; Moore and Schleppegrell 2014; Polias and Dare 2006; Ryshina-Pankova 2006, 2015; Ryshina-Pankova and Byrnes 2013; Yasuda 2015).

Although the findings from this small-scale research cannot be used to make generalizations regarding the implications for second or foreign language writing instruction, certain tentative implications can be drawn on two related issues: teacher training and material design for SFL pedagogy, and the function of writing in L2 acquisition. Despite the benefits shown in SFL-informed practices, some researchers contend that SFL theory is too technical to be an applicable framework for teacher education, and may impose overwhelming demands on teachers and teacher educators (Bourke 2005; Tardy 2009). Indeed, it requires greater knowledge about language than is expected in the other approaches to L2 teaching. This may thus discourage teachers and teacher educators from applying this theory for literacy or language instruction (Schleppegrell 2004). In response to this critique, Macken-Horarik (2008: 43) argues for “ a good enough grammatics”. She maintains that while teachers require a level of SFL language that is “functional, stretchable and good for teachers to think with,” re-training teachers as theoretical linguistics is not necessary (Macken-Horarik 2008: 47, see also Macken-Horarik et al. 2001). One study conducted by Gebhard, Chen, Graham, and Gunawan on SFL and teacher education (2013) evinces that a “good enough grammatics” is achievable in the context of a 14-week MA TESOL course, in that the teachers on this were able to learn basic SFL theory, and later to use SFL genre-based pedagogy to design curricula and instruction for a variety of learners in a variety of contexts. Another study by Macken-Horarik et al. (2015) proposes a framework to enhance English teachers’ linguistic subject knowledge based on systemic functional linguistics . Their study also indicates that English teachers who received short-term training in SFL grammatics were able to enhance their awareness of the relationship between genre and its grammatical resources, and to apply this functional approach to literacy instruction in their specific contexts. These studies offer some indications of how to successfully implement SFL theory in L2 education, but more research is necessary in order to reveal its potential applications to L2 instruction beyond English.

The present study demonstrates the language learning potential of L2 writing , as proposed by several researchers noted above. As well-argued by Cumming (1990) and Swain and Lakpin (1995), the act of writing is inherently a problem-solving activity, which is conducive to consolidating and increasing mastery over one’s L2 knowledge, as well as generating new linguistic knowledge. This assumption is further supported by empirical studies exploring the interface of SLA and L2 writing. As summarized in Manchón (2011a), these studies find that during writing learners tend to focus their attention on linguistic forms, formulate hypotheses about these and the related functions, generate and assess linguistic options, as well as engage in metalinguistic reflection. This indicates that cognitive restructuring is triggered in L2 learning, though most writing tasks utilized in these earlier studies were not self-produced compositions but controlled and grammar-focused activities (i.e. cloze tests) or editing tasks. Nevertheless, to establish any causal relationship between composition writing and L2 learning, further research is needed to examine the writing-to-learn language dimension of L2 writing development and instruction across different language and instructional settings.

The progress made by CSL inexperienced writers in this study offers hope that instruction in this approach may prove effective in raising CSL writing skills. Nevertheless, due to the lack of a comparison group, it seems impossible to attribute their improvements from the pre-test to the post-test, purely to the effects of this pedagogical intervention. However, by taking participant responses to the questionnaire into account, this research can conclude that this approach positively influenced students’ textual meaning -making in Chinese. As an exploratory study examining the pedagogical affordances in relation to CSL/ CSL instruction, further research is strongly recommended to adopt a more robust method to measure causality (e.g. an experimental approach) to verify the empirical findings uncovered in this work and show to what extent the SFL approach can outperform other educational options in different educational levels and settings, and for a broader variety of learners. This line of studies can perhaps convince CSL/CFL textbook writers or material developers to apply this approach as a viable framework to designing Chinese learning materials. Such an undertaking could alleviate the burden for Chinese language teachers who are interested in adapting this approach for their classroom, but could be baffled by its technical complexity. The present study thus throws some light on this issue by presenting an revelatory case, in which carefully designed SFL -informed materials were offered to the two participating teachers with no prior knowledge or experience of SFL theory.

Another limitation of this study is the rather short-time span of the pedagogical implementation. Although participants were allowed to access this instructional software during the experimental period, it undeniably takes a greater amount of time and practice to transfer receptive language knowledge into productive knowledge, as indicated in students’ comments on the open-ended question. Repeated exposure to this multi-media writing program for a longer period of time would probably be more effective than a limited number of classroom lessons in learning to compose better Chinese texts. Further research can thus conduct a longitudinal study of this approach using these online instructional materials to learn more about in what ways and to what extent it can benefit CSL novice writers.

The third flaw of this study, common to most contrived research, is that it was not conducted in a natural classroom setting. Several learner variables, such as affect, motivations , beliefs and goals, may play a mediating role in their text construction and perceptions of this pedagogical approach stated in the questionnaire. Given that the writing completed for this project was not related to their course assessment, they may not have been well-motivated to do their best. Additionally, the participants were informed beforehand of the purpose of this study, and may have been inclined to provide positive answers in the questionnaires. All these practical limitations of data collection should be borne in mind while interpreting the current findings and thus the present study opens several avenues for future research as discussed above.

6 Conclusion

As a pilot study to investigate the feasibility of incorporating an SFL -informed approach to CSL classroom, some tentative findings observed from the progress made in students’ written texts and positive evaluations in their responses to the questionnaire suggest that the instruction attending to the ideational, interpersonal and textual features associated with a specific genre can contribute to a heightened awareness and deployment of genre-related language resources, and so improve the learners’ subsequent construal of textual meaning . Given the very exploratory nature of this research, it is hoped that the present study can motivate more CSL research to study learners’ communicative competence at the discourse level and endeavor to extend the current study to more advanced Chinese learners, or to uncover other effective pedagogical approaches that can be used to improve their communicative abilities. This line of research is urgently needed, as in the future more CSL learners will need Chinese as their working language to meet their academic and career needs.

References

Achugar, M., & Colombi, M. C. (2008). Systemic functional linguistic explorations into the longitudinal study of advanced capacities: The case of Spanish heritage language learners. In L. Ortega & H. Byrnes (Eds.), The longitudinal study of advanced L2 capacities (pp. 36–57). London: Routledge.

Bassetti, B. (2005). Effects of writing systems on second language awareness: Word awareness in English learners of Chinese as a foreign language. In V. Cook & B. Bassetti (Eds.), Second language writing systems (pp. 335–356). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Bourke, J. (2005). The grammar we teach. Reflections on English Language Teaching, 4, 85–97.

Byrnes, H. (2009). Emergent L2 German writing ability in a curricular context: A longitudinal study of grammatical metaphor. Linguistics and Education, 20, 50–66.

Byrnes, H. (2013). Positioning writing as meaning-making in writing research: A introduction. Journal of Second Language Writing, 22, 95–106.

Caffarel, A. (2006). Learning advanced French through SFL: Learning SFL in French. In H. Byrnes (Ed.), Advanced language learning: The contribution of Halliday and Vygotsky (pp. 204–224). London: Continuum.

Chen, C.-Y., & Shi, M.-L. (1999). A note on NP-topics in second language acquisition of Chinese. Studies in English Literature and Linguistics, 25, 133–157.

Chen, H.-C., Hsu, C.-C., Chang, L.-Y., Lin, Y.-C., Chang, K.-E., & Sung, Y.-T. (2013). Using radical-derived character E-learning platform to increase learner knowledge of Chinese characters. Language, Learning and Technology, 17, 89–108.

Cheng, F.-W. (2008). Scaffolding language, scaffolding writing: A genre approach to teach narrative writing. Asian EFL Journal, 10, 167–191.

Colombi, M. C. (2002). Academic language development in Latino students’ writing in Spanish. In M. J. Schleppegrell & M. C. Colombi (Eds.), Developing advanced literacy in first and second languages: Meaning with power (pp. 67–86). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Colombi, M. C. (2009). A systemic functional approach to teaching Spanish for heritage speakers in the United States. Linguistics and Education, 20, 39–49.

Cumming, A. (1990). Metalinguistic and ideational thinking in second language composing. Written Communication, 7, 482–511.

Duff, P. A., & Li, D. (2002). The acquisition and use of perfective aspect in Mandarin. In R. Salaberry & Y. Shirai (Eds.), Tense-aspect morphology in L2 acquisition (pp. 417–453). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Gebhard, M., Chen, I.-A., Graham, H., & Gunwan, W. (2013). Teaching to mean, writing to mean: SFL, L2 literacy, and teacher education. Journal of Second Language Writing, 22, 107–124.

Gebhard, M., Chen, I.-A., & Britton, L. (2014). “Miss, nominalization is a nominalization:” English language learners’ use of SFL metalanguage and their literacy practices. Linguistics and Education, 26, 106–125.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1994). An introduction to functional grammar (2nd ed.). London: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. (2014). Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar. London: Routledge.

Harklau, L. (2002). The role of writing in classroom second language acquisition. Journal of Second Language Writing, 11, 329–350.

Harman, R. (2013). Literary intertextuality in genre-based pedagogies: Building lexical cohesion in fifth-grade L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 22, 125–140.

Huang, J., & Mohan, B. (2009). A functional approach to integrated assessment of teacher support and student discourse development in an elementary Chinese program. Linguistics and Education, 20, 22–38.

Kuo, J. Y., Wu, J.-S., & Chung, S.-C. (2011). Computer assisted learning of Chinese shape classifiers. Journal of Chinese Language Teaching, 8, 99–122.

Leki, I. (2009). Preface. In R. Manchon (Ed.), Writing in foreign language contexts: Learning, teaching, and research (pp. xiii–xxvi). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Liardét, C. L. (2013). An exploration of Chinese EFL learner’s deployment of grammatical metaphor: Learning to make academically valued meanings. Journal of Second Language Writing, 22, 161–178.

Macken-Horarik, M. (2002). “Something to shoot for”: A systemic functional approach to teaching genre in secondary school science. In A. M. Johns (Ed.), Genre in the classroom: Multiple perspectives (pp. 17–42). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Macken-Horarik, M. (2008). A “good enough” grammatics: Developing an effective metalanguage for school English in an era or multiliteracies. In C. Wu, C. Matthiessen, & M. Herke (Eds.), Proceedings of the ISFC 35: Voices around the world (pp. 43–48). Sydney: 35th ISFC Organizing Committee.

Macken-Horarik, M., Love, K., & Unsworth, L. (2001). A grammatics “good enough” for school English in the 21st century. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 34, 9–23.

Macken-Horarik, M., Sandiford, C., Love, K., & Unsworth, L. (2015). New ways of working ‘with grammar in mind’ in School English: Insights from systemic functional grammatics. Linguistics and Education, 26, 145–158.

Manchón, R. M. (2009). Broadening the perspective of L2 writing scholarship: The contribution of research on foreign language writing. In R. M. Manchón (Ed.), Writing in foreign language contexts: Learning, teaching, and research (pp. 1–19). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Manchón, R. M. (Ed.). (2011a). Learning-to-write and writing-to-learn in an additional language. Philadelphia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Manchón, R. M. (2011b). Situating the learning-to-write and writing-to-learn dimensions of L2 writing. In R. M. Manchón (Ed.), Learning-to-write and writing-to-learn in an additional language (pp. 3–14). Philadelphia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Manchón, R. M. (2011c). Writing to learn the language: Issues in theory and research. In R. M. Manchón (Ed.), Learning-to-write and writing-to-learn in an additional language (pp. 61–82). Philadelphia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Martin, J. (2009). Genre and language learning: A social semiotic perspective. Linguistics and Education, 20, 10–21.

Mohan, B., & Huang, J. (2002). Assessing the integration of language and content in a Mandarin as a foreign language classroom. Linguistics and Education, 13, 405–433.

Moore, J., & Schleppegrell, M. (2014). Using a functional linguistics metalanguage to support academic language development in the English Language Arts. Linguistics and Education, 26, 92–105.

Ortega, L. (2012). Epilogue: Exploring L2 writing-SLA interfaces. Journal of Second Language Writing, 21, 404–415.

Polias, J., & Dare, B. (2006). Towards a pedagogical grammar. In R. Whittaker, M. O’Donnell, & A. McCabe (Eds.), Language and literacy: Functional approaches (pp. 123–143). London: Continuum.

Ryshina-Pankova, M. (2006). Creating textual words in advanced learner writing. The role of complex theme. In H. Byrnes (Ed.), Advanced language learning: The contribution of Halliday and Vygotsky (pp. 164–183). London: Continuum.

Ryshina-Pankova, M. (2015). A meaning-based approach to the study of complexity in L2 writing: The case of grammatical metaphor. Journal of Second Language Writing, 29, 51–63.

Ryshina-Pankova, M., & Byrnes, H. (2013). Writing as learning to know: Tracing knowledge construction in L2 German compositions. Journal of Second Language Writing, 22, 179–197.

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2004). The language of schooling: A functional linguistics perspective. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbuam.

Shen, H., & Ke, C. (2007). Radical awareness and word acquisition among non-native learners of Chinese. Modern Language Journal, 91, 97–111.

Swain, M., & Lakpin, S. (1995). Problems in output and the cognitive processes they generate: A step toward second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 16, 371–391.

Tardy, C. M. (2009). Building genre knowledge. West Lafayette: Parlor Press.

Teruya, K. (2006). Grammar as a resource for the construction of language logic for advanced language learning in Japanese. In H. Byrnes (Ed.), Advanced language learning: The contribution of Halliday and Vygotsky (pp. 109–133). London: Continuum.

Teruya, K. (2009). Grammar as a gateway into discourse: A systemic functional approach to SUBJECT, THEME, and logic. Linguistics and Education, 20, 67–79.

Troyan, F. J. (2014). Leveraging genre theory: A genre-based interactive model for the era of the common core state standards. Foreign Language Annals, 47, 5–24.

Tsai, C.-H., Kuo, C.-H., Horng, W.-B., & Chen, C.-W. (2012). Effects on learning logographic character formation in computer-assisted handwriting instruction. Language, Learning and Technology, 16(1), 110–130.

Urquhart, S., & Weir, C. J. (1998). Reading in a second language: Process, product, and practice. New York: Longman.

Wang, M., Perfetti, C., & Liu, Y. (2003). Alphabetic readers quickly acquire orthographic structure in learning to read Chinese. Scientific Studies of Reading, 7, 183–208.

Wee, L.-H. (2007). Unraveling the relation between Mandarin tones and musical melody. Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 35, 128–144.

Weissberg, R. (2008). Critiquing Vygotskian approach to L2 literacy. In D. Belcher & A. Hirvela (Eds.), The oral-literate connection (pp. 26–45). Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Williams, J. (2012). The potential role(s) of writing in second language development. Journal of Second Language Writing, 21, 321–331.

Yasuda, S. (2015). Exploring changes in FL writers’ meaning-making choices in summary writing: A systemic functional approach. Journal of Second Language Writing, 27, 105–121.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix A: Sample Instructional Materials

Example 1

One screenshot of ideational function (old version)

English Translation of Example 1 Materials

-

2.

Ideational language resources

* How to describe a dish

-

2.1: Food taxonomy

Basic terms for major food types

-

2.2: Food description

Adjectives and verbs to describe food flavor

-

2.1: Food taxonomy | 2.2: Food description |

|---|---|

Meat | Verbs |

chicken, pork | taste, smell |

Seafood | Adjectives |

crab, shrimp | sour, sweet, bitter, spicy |

Fruit | |

apple, orange |

Example 2

One screen shot of ideational function (new version)

English Translation of Example 2 Materials

Q: What does it taste like?

Example 3

One screenshot of brainstorming strategies

English Translation of Example 3 Materials

Brainstorming strategy: Step 2: writing aspects

-

First, brainstorm some questions related to the topic.

-

Take the topic “My favorite food is Thai Spicy Soup” for instance.

1.2 Appendix B: An Example of Chinese Writing Prompt

Topic A

我最喜歡吃的一種台灣食物

請你班上的同學說明,你所吃過的台灣食物中,有哪一道菜或小吃你很喜歡?這道菜或食物有什麼特別的地方(顏色/氣味/味道/材料/做法...)? 你為什麼會特別喜歡吃這種食物?

English Translation of Topic A

Among the foods/dishes that you have ever tasted in the past, what’s your favorite meal or snack? Please show your classmates in what ways this food is special with regard to its color, smell, flavor, ingredients, or recipes from your own perspective.

1.3 Appendix C: Assessment Scheme for Pre-/Posttest Essays

Category | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Content development | Little attempt is made to state the subject of the text. The content is poorly focused on the topic . | The text attempts to address the subject of the essay but few details are given and some ideas are unclear. | The text focuses on the subjects of the essay but sometimes strays from the topic. Ideas are not well-developed and more details are needed. | The text focused on the topic and main idea is clear but the supporting information is general. There are a few vivid details in the essay. | The text is well-focused on the topic. Concrete details, sensory imagery and emotional response adequately support the description of the selected food. Ideas are well-supported with details. | Clear ideas are well-supported with interesting and vivid details. Several relevant, telling, quality details give the readers important information that allows the readers to picture, smell, feel or imagine tasting things described. |

Organization & coherence | There is no clear organization and no transitions. The text is impossible to follow. | The text is poorly organized with few transitions and is difficult to follow. | The structure of the text is clear, but some details and transition words and phrases are not in a logical or expected order, which distracts the readers. | The structure of the text is clear but some lapses in organization. It is usually easy to follow with apparent use of some transitions. | The text has logical organization and excellent transitions with occasional lapses. It is easy to follow. | The text is well-structured with introduction, body and conclusion. Details and transition words and phrases are placed in a logical order and the way they are presented effectively keeps the interest of the reader. |

Word choice | The language is too basic and weak; ineffective for description. | The language is somewhat weak with very limited word choices. | The wording is bland and little apparent effort to replace common words with vivid words. More descriptive words are needed. | The writer uses words that communicates clearly and includes some vivid words but sometimes the words are used inaccurately. | The writer employs vivid and somewhat varied word choices. It demonstrates reaching towards mature language, but occasionally the words are used inappropriately. | The writer effectively uses precise, interesting and vivid words/phrases that linger or draw pictures in the reader’s mind. The writer can command a wide variety of word choices. |

Grammar | Sentences lack structures and are incomplete or rambling. There are serious errors that interfere with the reader’s understanding of the essay. | There are frequent errors in sentence structure that distract the readers. | There are some problems or errors with sentence structure. Occasional sentence fragments or run-on sentences. | Most sentences are correctly constructed but simple sentence structure is used repeatedly. There are some errors but these errors do not distract the reader. | Most sentences are well-constructed with varied structure. There are few errors in grammar. | All sentences are well-constructed with varied structure and lengths. There are no errors in grammar. |

1.3.1 Chinese version of assessment scheme

評量向度/級分 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

文意發展 Content development | 文章內容不甚符合題目要求,且大部份內容與主題無關。 | 雖嘗試依據題目及主旨選取材料,但所選取之材料相當不充分或未能具體描述食物相關內容;部分內容難以理解。 | 嘗試依據題目及主旨選取材料,但部分所選取之材料不夠適切或具體食物陳述發展不夠充分。 | 能依據題目及主旨選取材料,但具體食物陳述、感官的描寫以及感受的鋪陳仍不夠充分。 | 能依據題目及主旨選取相關材料並能充分提供具體食物的細節、感官的描寫以及感受的鋪陳。 | 能依據題目及主旨選取適當材料,並能進一步提供具體有力食物相關細節支持、詳盡生動的感官描述、以及活潑的感受鋪陳,以凸顯文章之主旨。 |

結構組織 Organization & coherence | 沒有明顯之文章結構,文句銜接極差。 | 結構本身不連貫,文句銜接不佳。 | 文章雖具結構(有起頭也有結尾)卻鬆散,且前後不連貫;文句銜接不甚理想。 | 文章結構稍嫌鬆散(前後發展比例欠妥),或偶有不連貫、轉折不清之處;文句銜接大致良好。 | 文章結構大致完整(前後發展比例恰當),但偶有轉折不流暢之處;文句銜接良好。 | 文章結構完整(有開頭、發展、及結尾),段落分明,內容前後連貫,並能運用適當之連接詞連貫全文;文句銜接極佳具邏輯性。 |

語詞使用 word choice | 用字遣詞有很多錯誤或甚至完全不恰當。 | 用字遣詞常有錯誤。 | 描述食物用字遣詞不夠精確,或不夠豐富,出現錯誤。 | 描述食物用字遣詞還算豐富但有些用語使用不當,文意表達尚稱清楚,但有時會出現冗辭。 | 描述食物用字遣詞較豐富,僅有少數用語使用不當,能正確使用與主旨相關語詞,語意表達清楚。 | 描述食物用字遣詞豐富,能正確使用與主旨相關語詞,並能應用成語,語意表達清楚細膩。 |

描述食物詞彙量相當有限。 | ||||||

文法句構 (grammar) | 文句支離破碎,語法掌握極差。 | 構句常有錯誤,基本語法掌握不佳。 | 構句不甚精確,或出現錯誤,或贅句過多,且語法錯誤較多。 | 大致能正確使用構句,僅有少數語法錯誤。 | 能運用各種句型,使文句通順,語法少有錯誤。 | 構句正確文句流暢,並活用各種句型,語法幾乎無誤。 |

1.4 Appendix D: Student’s Chinese Texts with English Translations

1.4.1 Mohammad’s Writing Samples

Pre-test

在台灣我吃了一些台灣食物. 我覺得台灣食物有自己的特色. 但是在這裡有一道菜我最喜歡的應為我覺得很特別而且在我們國家我沒有看過有人賣這種食物. 這道菜就是火雞肉飯.

In Taiwan, I have tasted some Taiwanese food. I think Taiwanese food has its own unique features. But there is one Taiwanese food I love most, because I think it is very special and in my country I have never seen anyone selling this kind of food. This is the turkey rice.

Post-test

我是印尼來的學生.在台灣我吃了一些台灣食物. 我覺得台灣食物大部分都很好吃,每一道菜也有自己的特色.但是在這裡有一道菜我最喜歡的. 因為我覺得很特別而且在我們國家沒有人賣這食物. 這道菜叫座火雞肉飯. 這道菜的材料主要有火雞肉, 米飯, 和醬油. 雖然看起來很簡單, 但是這道菜聞起來很香, 吃來也很好吃.我最常去火車站附近的一家飯館吃這道料理. 在嘉義這道菜很有名, 很多人喜歡吃這道菜.所以沒吃過這道菜的人一定要試試看.

I am a student from Indonesia. In Taiwan, I have tasted some Taiwanese food. I think most Taiwanese food is very delicious. Each has its own unique features. But there is one Taiwanese food I love most. This is because I think it is very special, and in my country no one sells this kind of food. This dish is called the turkey rice. The main ingredients are turkey, rice and soy sauce. Although this food looks easy to make, it smells sweet and tastes delicious. I often go to a restaurant near the train state to try this food. In Chiayi this food is well-known, and many people love this food. Therefore, if you have not tried it, you must give it a try.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Cheng, FW. (2017). Construing CSL Writing as Meaning-Making: A Genre-Based Approach. In: Kecskes, I. (eds) Explorations into Chinese as a Second Language. Educational Linguistics, vol 31. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54027-6_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54027-6_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-54026-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-54027-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)