Abstract

A social psychology of problem behavior was employed in a longitudinal study of high school youth to predict time of onset of marijuana use. Measures of 19 personality, perceived environment, and behavioral variables among nonusers of marijuana in 1970 were shown to account for a significant amount of the variance in time of onset of use over the subsequent 2-year period (R = .61 for males and .44 for females). More important perhaps, “growth curves” of the measures plotted over the study years show that the trajectory of social-psychological development varies depending on whether and on when onset of marijuana use occurs. The findings support the importance of the concept of deviance or transition proneness in the social-psychological framework as identifying a disposition toward development and change among adolescents.

Reprinted with permission from:

Jessor, R. (1976). Predicting time of onset of marijuana use: A developmental study of high school youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 44(1), 125–134.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Marijuana use

- Problem behavior proneness

- Transition proneness

- Psychosocial development

- Social psychology of problem behavior

- Problem Behavior Theory

- Co-variation of problem behaviors

This chapter reports the use of a social psychology of problem behavior to account for onset and for variation in time of onset of marijuana use among high school youth . It represents an effort to go beyond epidemiological and descriptive studies of prevalence; instead, it seeks to embed marijuana use in a theoretical framework that enables systematic prediction of its occurrence and that reveals the relation of its occurrence to adolescent development as a whole. Since the framework has been described elsewhere (Jessor, Collins, & Jessor, 1972; Jessor, Graves, Hanson, & Jessor, 1968; R. Jessor & S. L. Jessor, 1973a, 1973b; S. L. Jessor & R. Jessor, 1974, 1975; Jessor, Jessor, & Finney, 1973; Rohrbaugh & Jessor, 1975; Weigel & Jessor, 1973), and since the very same paradigm has recently been applied to predicting the onset of drinking (R. Jessor & S. L. Jessor, 1975), only a brief introduction is given here.

The concept of “problem behavior” or “deviance” refers to behavior that departs sufficiently from the regulatory norms of the larger society to result in or evoke or imply some sort of social control response. Much of what constitutes problem behavior in adolescence, however, is relative to age-graded norms , norms that may proscribe the behavior for those who are younger while permitting or even prescribing it for those who are older. Such behaviors, for example, engaging in sexual intercourse, come to be seen as characterizing the occupancy of a more mature status and hence engaging in them for the first time can serve to mark a transition in status from “less mature” to “more mature” for an adolescent. It is in this regard that a social psychology of problem behavior becomes relevant to processes of adolescent growth and development. The theoretical aim of specifying a proneness to engage in problem behavior becomes largely synonymous with the aim of specifying a proneness toward transition among adolescents. By theoretically mapping the concept of “transition proneness ” onto the concept of “deviance proneness ,” it is possible to exploit the developmental implications of Problem Behavior Theory in adolescence .

A fairly comprehensive social psychology comprising three major explanatory systems—personality, the perceived social environment, and behavior—has been employed. Within each system, variables are specified that have logical implications for the likelihood of occurrence of problem behavior or of conformity. In the personality system, values and expectations for achievement and independence, personal beliefs such as social criticism, internal-external control, alienation, and self-esteem, and personal controls such as altitudinal tolerance of deviance and religiosity are some of the major variables assessed. In the perceived social environment system, the main variables are social-psychological rather than demographic; they include value compatibility between parents and friends, relative influence of parents versus friends, parental supports and controls, parent attitude toward deviance, and friends’ approval of and models for deviance. The behavior system is comprised of various problem behaviors (marijuana use, problem drinking, premarital sexual intercourse, and general deviant behavior such as aggression, lying, and stealing) and various conventional behaviors (church attendance and school achievement). Problem behavior, in this social-psychological framework, is conceptualized as the outcome of the interaction of variables that instigate or conduce toward departure from norms and of variables that control against such transgression; in terms of the theory, the pattern of variables constitutes a deviance proneness or a proneness to engage in problem behavior.

Four important questions are addressed in the present research. First, is there a pattern of personality, environment, and behavioral attributes among nondrug users that constitutes a proneness or a social-psychological “readiness” to begin use of marijuana? Second, does such a prior pattern signal not only onset but also variation in time of onset? Third, is variation in time of onset of marijuana use systematically related to variation in the developmental trajectories of the associated personality, social, and behavioral attributes? And fourth, is length of time since onset related to prevalence of other problem or transition-marking behaviors?

Method

Participants

In the spring of 1969, a random sample of 1126 students stratified by sex and grade level was designated in Grades 7, 8, and 9 of three junior high schools in a small city in the Rocky Mountain region. Students were contacted by letter and asked to participate over the next 4 years in a study of personality, social, and behavioral development. Parents were also contacted and asked for their signed permission. Permission was received for 668 students and, of these, 589 (52% of the random sample) were tested in April 1969, becoming the Year 1 cohort of the study. By the end of the Year 4 (1972) testing, 483 students were still in the study, representing 82% retention of the initial cohort. Of these, there were 432 students (188 boys and 244 girls) for whom there was no missing year of data, and this latter group constituted our core sample for longitudinal or developmental analyses. Demographically, the core sample is relatively homogeneous—almost entirely Anglo-American in ethnic background and middle -class in socioeconomic status.

Procedure

Data were collected annually in April–May of each year, 1969–1972, by means of an elaborate, theoretically derived questionnaire requiring about 1½ hours to complete. The questionnaire consisted largely of psychometrically developed scales or indices assessing the concepts in the social-psychological framework. Administration of the questionnaire took place outside of class in small group sessions. A guarantee of strict confidentiality was given since participants had to sign their names in order to permit annual follow-up. Reaction to the questionnaire was, in general, one of strong personal interest, and the quality of the self-report data can be considered to be very high.

Establishment of Marijuana Onset Groups

In order to address the four major questions slated in the introduction, it was necessary to classify the students as to their experience with marijuana over the study years. Since information about marijuana use was not collected in the initial year, 1969, it is possible to classify students as to their use or nonuse only for 1970–1972. During these years, among a variety of other questions about drug use, students were asked: “Have you ever tried marijuana?” (response categories: never, once, more than once), and “Did your first experience with drugs take place within the past 12 months?” (response categories: yes, no). On the basis of their responses to these questions, students were classified as users (response of more than once) or as nonusers for each of the three yearly intervals, 1969–1970, 1970–1971, and 1971–1972. From these classifications, it was possible to establish the marijuana onset groups required for the present analyses. Four groups were established: (a) nonusers (n = 258; 113 males and 145 females): those students who reported no use of marijuana over the study years; (b) initiates 1971–1972 (n = 45; 24 males and 21 females): those students who began use of marijuana in the last year of the study; (c) initiates 1970–1971 (n = 48; 18 males and 30 females): those students who began use of marijuana a year earlier than the preceding group; and (d) users (n = 69; 26 males and 43 females): those students already using marijuana before the 1970 testing. (The total N of 420 is less than the 432 in the core developmental sample since there were five students with missing data and seven students from the user group, four males and three females, who reported subsequent discontinuation of marijuana use and were therefore dropped from these analyses. Groups b, c, and d, it follows, were all current users in 1972.)

The groups are ordered, therefore, in relation to time of onset of marijuana use, the nonusers showing no onset, the initiates 1971–1972 showing latest onset, and the initiates 1970–1971 showing earliest onset among these three groups none of whom had yet begun use as of 1970; the users, of course, having already begun prior to 1970, constitute an important reference group against which to compare the other three. In terms of our basic interest in deviance or transition proneness , an examination of these four transition groups on the social-psychological measures collected in 1970 should reveal whether there is an ordering on the measures that is consonant with —and therefore predictive of—the subsequent order of onset of marijuana use.

Measurement of the Social-Psychological Variables

The measures of the variables in the personality, perceived environment, and behavior systems have been described elsewhere (e.g., see R. Jessor & S. L. Jessor, 1975). Details regarding the item content and the scoring of the 1969 version of the questionnaire appear in Jessor (1969). For the most part, the scales have very adequate psychometric properties as shown by Scott’s homogeneity ratio and Cronbach’s alpha index of reliability. Measurement stability over time, as indicated by interyear correlations, is substantial, and various kinds of validity, including construct validity, have been established in the various studies cited earlier.

Results

The results are organized around the major questions stated in the introduction. First, data—both univariate and multivariate—are presented to enable the assessment of the predictability of onset and of time of onset of marijuana use. Second, figures showing the developmental trajectories of several of the social-psychological predictors over the study years are presented to enable examination of the degree to which marijuana onset is associated with personality, social, and behavioral development. And third, data on the prevalence of other problem or possible transition behaviors permit an appraisal of the degree to which they covary with the length of time since onset of marijuana use.

Predicting Onset and Time of Onset of Marijuana Use

The first approach to predicting onset from antecedent measures was to examine the mean scores of the four groups on the theoretical variables in 1970 when only one of the groups had experience with marijuana but the other three had not. Since the data for males and females are very similar, they are presented for the sexes combined. The means and the associated F ratios for 19 theoretical variables are shown in Table 9.1.

The data in Table 9.1 provide substantial support for the relation of marijuana onset to a deviance- or transition-prone pattern of social-psychological attributes existing prior to onset. Group a, the nonusers who reported no onset during the study years, had the most conventional or least deviance-prone scores on each of the measures. They had the highest value on achievement, the lowest value on independence, the smallest independence-achievement value disjunction, and the highest expectations for achievement within the motivational instigation structure of the personality system. In terms of personal beliefs, nonusers were least alienated and least socially critical; and in terms of personality controls, they showed the highest attitudinal intolerance of deviance, strongest religiosity, and highest negative functions of (reasons against) drug use. With regard to the distal structure of the perceived social environment system, nonusers evidenced the greatest parents-friends compatibility, the greatest influence of parents relative to that of friends (the lower the score, the greater the parent influence), and the greatest parental support and controls . In the proximal structure, nonusers reported least friends’ and parents’ approval of drug use and least friends’ models of drug use. With respect to the behavior system, finally, the nonusers had the lowest deviant behavior score and reported the largest frequency for church attendance and the highest grade point average. This remarkably consistent pattern is, theoretically, the pattern that is most conventional or conforming in nature.

The pattern gains significance from the fact that in almost every case, Group d, the old users, was the group whose mean scores provide the most extreme contrast—the pattern that is, as expected, most deviance prone. And, of crucial importance, the mean scores of Groups b and c are, on most of the variables, ordered exactly in accord with their order of subsequent onset of use, with Group b being closer to Group a and Group c being closer to Group d. The overall F ratios, with few exceptions, are highly significant. These data, then, provide pervasive support of the relationship of theoretically deviance- or transition-prone attributes to both onset and time of onset of marijuana use during adolescence.

The second approach to predicting time of onset enables an appraisal of the strength of the overall framework. Multiple regression analyses were carried out using the 1970 measures as predictors and time of onset (membership in Group a, b, or c) as the criterion score. Group d was not included so that the criterion score could represent variation in time of onset among students who were all nonusers in 1970. The multiple correlations for a set of predictors similar to those listed in Table 9.1 were .61 for males, .44 for females, and .49 for the sexes combined. All of these are significant at p < .001, thus providing direct support for the usefulness of the theory in predicting onset of marijuana use.Footnote 1

Another way of examining the relation of the social-psychological variables to variation in onset of marijuana use is to compare the groups on the same measures at the end of the study, in 1972. Mean scores in 1972 should reflect variation in length of involvement with marijuana, that is, the outcome of the transition. The data relevant to this issue are presented in Table 9.2.

The data in Table 9.2 are strongly related to the time of onset variation. In a number of instances, the means of the two groups that made the transition, Groups b and c, moved closer to the mean of Group d and further away from Group a, the group that did not make the transition to use. The multiple correlations against the onset criterion score were considerably higher: .69 for males, .72 for females, and .68 for the sexes combined. Thus, the 1972 measures of the social-psychological framework account for nearly 50% of the variance in the onset criterion, almost twice as much as was accounted for by the 1970 antecedent measures.

Onset of Marijuana Use and Social-Psychological Development

The demonstration of a social-psychological readiness to begin use of marijuana that is in fact predictive of its onset and the demonstration that time since onset is related to subsequent social-psychological outcome both suggest that the course of social-psychological development during adolescence should vary depending on whether and when marijuana use begins. This issue is addressed in this section by plotting the actual course of development over the study years of the four transition groups on a variety of measures of the theoretical variables. For many of the variables, scores are available for all four years, 1969–1972, whereas for others they are available only in the latter 3 years.

Fig. 9.1 presents the “growth curves” of attitude toward deviance (the higher the score the greater the intolerance) for the four transition groups for 1969–1972. The nonusers (Group a) were most intolerant in 1969 and remained most intolerant throughout; while becoming significantly more tolerant over the years, they nevertheless were still less tolerant in 1972 than any of the other groups in 1969. Group d, the users, was the group most tolerant of deviance in 1969, and they showed no significant change over the study years on this measure. The two groups that make the transition from nonuse to use during the study are intermediate in tolerance of deviance at the outset, and both become significantly more tolerant by the end. What is especially interesting is that the two initiate groups, originally significantly more intolerant than the users, converge on the latter group so that by 1972 there is no difference between their means, making the means of all three groups significantly different from the mean of the nonusers. Using marijuana has, it would appear, “homogenized” the two previously nonuser groups with Group d on this attitudinal measure of personal control. The curves in Fig. 9.1, then, evidence a systematic relation between the development of a personality attribute and the time of onset of marijuana use in adolescence.Footnote 2

Fig. 9.2 presents the curves for value on achievement and again the same characteristics are apparent. On this measure, the two initiate groups were close to the nonuser group in 1969, and all three were significantly higher than the user group. Although all groups declined in value on achievement over the study years, the slope was steeper for the initiate groups than for the nonusers, and by 1972 there was an evident convergence with the users. In 1972 there was no significant difference among the two initiate groups and the user group, and all three were significantly lower in value on achievement than the nonusers.

Fig. 9.3 represents the development of an attribute of the perceived environment, the perceived prevalence of friends models for drug use. Here again, across 1970–1972, the different courses of development associated with variation in time of onset of marijuana use are observable. Again there was convergence of the two initiate groups with the user group by 1972; what is of further interest is the fact that the steepest slope of increase for each initiate group occurred during its respective year of onset of marijuana use.

On another measure of the perceived environment, total friends’ approval for a variety of problem behaviors, the four groups were perfectly ordered in 1970 with regard to likelihood of onset, and the two transition groups again converged, by 1972, on the user group. In 1972, the three user groups were all significantly higher in total friends’ approval for problem behavior than the nonusers (Fig. 9.4).

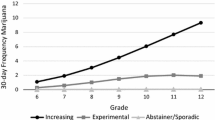

Fig. 9.5 represents a measure from the behavior system, general deviance, a measure that focuses on such behaviors as lying, stealing, property destruction, and aggression, and makes no reference to drug use, alcohol use, or sex. The curves are consistent in showing the developmental phenomena previously noted: the initial ordering in regard to likelihood of transition, the marked convergence on the mean of the user group, and, in this case again, the occurrence of the steepest slopes of increase in the year in which marijuana onset took place. In 1972, the nonusers were significantly lower in general deviant behavior than the other three groups, and there was no significant difference among the latter.

The figures, taken together, make a strong case for a systematic developmental relationship between onset of marijuana use and other social-psychological attributes. These findings are a unique and important outcome of the longitudinal research design.

Onset of Marijuana Use and Prevalence of Other Transition or Problem Behaviors

The relation of time of onset of marijuana use to prevalence of other problem or possible transition behaviors, for example, experience of sexual intercourse, problem drinking, or participation in activist protest, is shown in Table 9.3.

There is a significant relation between the onset of marijuana use and the prevalence of each of the three behaviors shown in Table 9.3. Both initiate groups showed higher prevalence in 1972 than the nonuser group, and the groups are ordered in direct relation to length of time since onset. Rates for these three behaviors in the early onset group are about three times the rates in the nonuser group, a difference in magnitude that is of obvious social significance. Thus, the onset of marijuana use cannot be seen as an isolated transition or behavior change but instead is related to other problem or transition behaviors—as it should be according to Problem Behavior Theory.

Discussion

The aim of this report has been to assess the utility of a social psychology of problem behavior for predicting the onset of marijuana use. Onset and time of onset were shown to be systematically related to a social-psychological pattern of attributes defined in the theory as deviance or transition proneness . That pattern includes lower value on achievement and greater value on independence, greater social criticism, more tolerance of deviance, and less religiosity in the personality system; less parental control and support, more friends’ influence, and more friends’ models and approval for drug use in the perceived environment system; more deviant behavior, less church attendance, and lower school achievement in the behavior system. The nonusers of marijuana tend to represent the opposite pattern, a pattern of relative conventionality or conformity.

Of special importance, the longitudinal data enabled the examination of the developmental trajectories of these theoretical attributes in relation to marijuana onset. It was quite clear that the course of adolescent development varies significantly in relation to whether and when marijuana onset occurs. Beginning to use marijuana is associated with a developmental divergence from nonusers and a convergence on the social-psychological characteristics of those who are already users. The word “associated” is important to stress since, of course, no causal interpretation of the relations among the changes is warranted.

Finally, it was shown that marijuana onset is related to the prevalence of other problem or transition-marking behaviors such as sexual intercourse experience, problem drinking, or participation in activist protest. The conclusion to be drawn is that deviance or transition proneness is not specific to a given behavior but constitutes instead a more general developmental notion.

Several limitations of the present study remain to be acknowledged. First, the fact that the participants in the longitudinal research represent only 52% of the originally designated random sample precludes generalizing to the larger population. Second, not all of the measures of the theoretical variables employed in the larger project were related to onset of marijuana use or showed differential change over time in relation to onset; these include measures of internal-external control, self-esteem, and values and expectations for affection. And third, while prediction of marijuana onset from antecedent characteristics was significant, it should be emphasized that only about 25% of the variance in the onset criterion was accounted for.

In evaluating the import of such limitations, several balancing points need to be kept in mind. The loss of 48% of the original random sample in no way constrains the kind of comparisons between groups in the sample that were the primary objective of this study. In addition, the obtained sample yielded a wide range of variation on all of the measures employed, variation that made the desired comparisons between groups entirely feasible. Further, since the 52% who did participate were those willing to make a voluntary commitment to 4 years of involvement, the validity of the self-report data on which the research rests was clearly enhanced. Another point is that the findings were not restricted to a small handful of measures; instead, an unusually large number of variables was assessed, and significant findings occurred on at least some measures in each of the three major social-psychological systems—personality, the perceived environment, and behavior—and in each of the theoretical structures within the three systems. Finally, the results are consonant with numerous other studies of marijuana use among youth. The relative unconventionality of users was reported by Suchman (1968) in his study of “the hang loose ethic.” The importance of peer models and support has been emphasized in Kandel’s work (1973), and by Sadava (1971) and Johnson (1973); and the relation between marijuana use and other problem behavior has emerged in a variety of studies (for useful reviews of the literature see Braucht, Brakarsh, Follingstad, & Berry, 1973; McGlothlin, 1975; Sadava, 1975). A study that, like ours, reports data collected before involvement with marijuana was done with college students (Haagen, 1970). Nevertheless, the antecedent differences between subsequent users and nonusers parallel those we have reported, especially in relation to variation in conventional orientations and behavior.

The utility of the theoretical concept of deviance or transition proneness has also been supported in our analyses of other possible transition-marking behaviors. These include the onset of drinking (R. Jessor & S. L. Jessor, 1975) and the shift from virginity to nonvirginity (S. L. Jessor & R. Jessor, 1975). The relations among these transitions are elaborated in a lengthy report of the overall study (R. Jessor & S. L. Jessor, 1977). The concept, as defined in relation to a social psychology of problem behavior, appears to identify an important disposition toward personal development and change in adolescents.

Notes

- 1.

In making inference to the social-psychological variables, it is important to rule out alternative factors that might account for findings such as group differences in age or in background characteristics. Although old users were significantly older than each of the three other groups, the difference between age means was small, ranging between 3 and 5 months. Among the three groups not yet using marijuana as of 1970, however, no difference between groups was as large as 2 months and none was significant. Hence, age could not be a factor in variation in time of onset among the 1970 nonuser groups. Another way of stating this is to report that among the nonusers in 1970 the correlation between age in months and time of onset was .07. With respect to demographic attributes, there were no differences among the transition groups in father’s occupation, father’s education, or mother’s education, or in the liberalism-fundamentalism of father’s or of mother’s religious group membership.

- 2.

All references in this section to differences being significant either over time for the same group or between different groups at a given time are based on two-tailed t tests with p < .05.

References

Braucht, G. N., Brakarsh, D., Follingstad, D., & Berry, K. L. (1973). Deviant drug use in adolescence: A review of psychosocial correlates. Psychological Bulletin, 79(2), 92–106.

Haagen, C. H. (1970). Social and psychological characteristics associated with the use of marijuana by college men. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University.

Jessor, R. (1969). General description of junior-senior high school questionnaire and its component measures. Socialization of problem behavior in youth research project report. Unpublished manuscript, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado.

Jessor, R., & Jessor, S. L. (1973a). Problem drinking in youth: Personality, social, and behavioral antecedents and correlates. In Proceedings, Second Annual Alcoholism Conference. NIAAA (pp. 3–23). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Jessor, R., & Jessor, S. L. (1973b). The perceived environment in behavioral science: Some conceptual issues and some illustrative data. American Behavioral Scientist, 16(6), 801–828.

Jessor, S. L., & Jessor, R. (1974). Maternal ideology and adolescent problem behavior. Developmental Psychology, 10(2), 246–254.

Jessor, R., & Jessor, S. L. (1975a). Adolescent development and the onset of drinking: A longitudinal study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 36(1), 27–51.

Jessor, S. L., & Jessor, R. (1975b). Transition from virginity to nonvirginity among youth: A social-psychological study over time. Developmental Psychology, 11(4), 473–484.

Jessor, R., & Jessor, S. L. (1977). Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press.

Jessor, R., Graves, T. D., Hanson, R. C., & Jessor, S. L. (1968). Society, personality, and deviant behavior: A study of a tri-ethnic community. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Jessor, R., Collins, M. I., & Jessor, S. L. (1972). On becoming a drinker: Social-psychological aspects of an adolescent transition. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 197, 199–213.

Jessor, R., Jessor, S. L., & Finney, J. (1973). A social psychology of marijuana use: Longitudinal studies of high school and college youth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 26(1), 1–15.

Johnson, B. D. (1973). Marihuana users and drug subcultures. New York: Wiley.

Kandel, D. B. (1973). Adolescent marihuana use: Role of parents and peers. Science, 181(4104), 1067–1070.

McGlothlin, W. H. (1975). Drug use and abuse. Annual Review of Psychology, 26, 45–64.

Rohrbaugh, J., & Jessor, R. (1975). Religiosity in youth: A personal control against deviant behavior. Journal of Personality, 43(1), 136–155.

Sadava, S. W. (1971). A field-theoretical study of college student drug use. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 3(4), 337–346.

Sadava, S. W. (1975). Research approaches in illicit drug use: A critical review. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 91(1), 3–59.

Suchman, E. A. (1968). The “hang-loose” ethic and the spirit of drug use. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 9(2), 146–155.

Weigel, R. H., & Jessor, R. (1973). Television and adolescent conventionality: An exploratory study. Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(1), 76–90.

Acknowledgments

The research reported here is part of a larger, longitudinal study of “The Socialization of Problem Behavior in Youth” supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Grant AA-00232, R. Jessor, principal investigator. The author is indebted to John Finney and Shirley L. Jessor for their invaluable contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jessor, R. (2017). Understanding the Initiation of Marijuana Use. In: Problem Behavior Theory and Adolescent Health . Advancing Responsible Adolescent Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51349-2_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51349-2_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-51348-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-51349-2

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)