Abstract

In this chapter, the two authors (François Combarnous and Eric Rougier) describe the empirical approach implemented throughout the different contributions of the book. The key assumption that variants of developing countries’ capitalist models can be characterized by a set of sector-related types of institutional governance is first formulated and elaborated. Then, the seven sectors to these governance sets are described and justified: labour, competition, social protection, education, and finance, standard in the comparative capitalism (CC) literature, to which agriculture and the environment have been added. Theoretical complementarities and possible trade-offs between these seven areas are then commented on, before the authors introduce the concepts of ex ante, ex post, progressive and regressive institutional complementarities in order to adapt the institutional complementarity theory to the specific context of developing countries. Ultimately, the theoretical articulation of economic and political institutions is described and the various consequences of this articulation for the analysis are drawn.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Institutional Governance

- Institutional System

- Institutional Reform

- Capitalist System

- Institutional Sector

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

The main ambition of this book is to analyse the capitalist systems of emerging market and developing countries. We have adopted a methodology that can provide unambiguous answers to the following questions: What do these emerging capitalism models look like? To what extent do they differ from what has been observed for OECD countries? How many different models are there? What are their main institutional and non-institutional characteristics? Do they exhibit significantly different socioeconomic outcomes? What sorts of institutional complementarity underlie these institutional systems? What has been the institutional trajectory of emblematic emerging countries like China, Brazil or South Africa? In order to address all the above questions, we have chosen to analyse and cluster the national institutional systems of a large sample of countries, including OECD, emerging and poor developing countries. Our method and results actually challenge the common hypothesis of globalization-led institutional convergence contending that several original models of capitalism have emerged in the developing world. In fact, emerging markets and developing countries’ capitalist systems do not necessarily all converge towards European or Anglo-Saxon models of capitalism, with most of the original models we uncover exhibiting particularly strong features of internal consistency or complementarity.

Our study is based on two main assumptions: (1) a capitalist economic system can be described as a system of sector-specific institutions; and (2) the way institutions in these different sectors are articulated determines the nature of their socioeconomic models and, therefore, their performance. More specifically, we analyse how the patterns of institutional governance specific to the different sectors of the capitalist economy—the goods market, the finance and credit sector, labour and production relations, education and training, social protection, agriculture and the environment—relate to one another, and give rise to specific, non-random configurations of capitalism. Our approach aims to be comprehensive, since it includes a wide range of countries at all levels of economic development, and also quantitative, since we gauge the institutional systems’ underlying capitalist economies by clustering various institutional indicators within the various constitutive sectoral dimensions of the system. Our work is also comparative, since it systematically analyses the cross-country similarities and differences between national institutional systems described by a specific set of sectoral types of governance.

This chapter first presents our working definition of capitalism as a system of complementary institutions (Section 3.2) and then goes on to expose our method in detail (Section 3.3). Section 3.4 explains how the institutional complementarity assumption, which was originally designed for the stabilized institutional systems of the mature OECD economies, has been adapted to the specific context of developing countries. The seven institutional sectors articulated by each capitalist system are subsequently presented and discussed (Section 3.5), before the political issues necessarily raised by any analysis of institutional systems are addressed in Section 3.6.

2 Capitalisms as Institutional Systems: Theoretical Considerations

Economic systems are composed of specialized agents and organizations whose actions are determined by overlapping layers of formal and informal institutions socially designed to reach specific goals (North 1990; North et al. 2008), the most common of which include securing individual property rights, reducing transaction costs and uncertainty and increasing organizational efficiency. Socioeconomic systems, because they are socially and historically conditioned, have understandably adopted different forms in different countries. Institutional diversity has been driven by the long-term historical process of institution-building, by which societies provide themselves with rules and norms that are in full accordance with their dominant social beliefs (North 1990; Aoki 2001). Other factors, whether global (globalized competition, information technological revolution) or local (geography, contingency, polity), have also, obviously, played their part in shaping country-specific forms of capitalism.

All these capitalism variations, however diverse they may be, are based on similar basic elements. The first element refers to capital accumulation guided by profit maximization. Since capital is costly, capitalists strive for resource optimization via technological and organizational innovations. Insofar as capital is privately owned by entrepreneurs or shareholders, private enterprise is inherently related to the accumulation of capital. Hence, institutions like property rights, corporate law or contracts are crucial for both the existence and expansion of capitalist systems. This is certainly one reason why CC scholars have essentially described varieties of capitalism in terms of the national differences in business and industrial relationships governance.

The second basic element of capitalism is the central role played by markets in allocating the means of production (labour and capital) and their output (goods and services) through the channel of market prices. Market mechanisms increase social utility, since they govern capital and labour movement from low to high private return activities. All privately owned assets, such as consumption and capital goods or labour, can be sold on markets, with transaction costs increasing due to information search or contract administration (North 1990). Market transactions need, therefore, to be efficiently governed so that transaction costs can be reduced. The mechanisms of trade governance remain local, and essentially relation- or reputation-based when markets are limited to arm’s length trade. Economic sophistication and growing asset specificity progressively require more formalized and centralized institutions—like property rights or contract laws, employer–employee bargaining rules, homogeneous land use or product market regulations—to be progressively designed and enforced in order to limit the likely increase in transaction costs (North 1990; Williamson 2000; Aoki and Hayami 2001; Greif 2005).Footnote 1

The third element of capitalism concerns the conflict over economic resources between social groups differentiated by their relation to capital or productive resources and, therefore, by the benefits they draw from the system. This sociopolitical conflict conditions institutional change (Amable 2003; Acemoglu et al. 2005). Hence, institutions that can attenuate such distributive conflicts are also required to support capitalism expansion over the long run (Rodrik 2007, 2008; North et al. 2008). In developing economies, however, the poorest social groups are generally unable to embark on struggles for institutional change, both because of time and resource limitations and collective action problems (Bardhan 2005). So although social conflict certainly exists in developing countries, it does not automatically translate into institutional change.

One crucial implicit hypothesis behind CC, and our work in this book, is that the coherence of the various national models of capitalism can be assessed by analyzing their institutional system as a system of sectoral types of institutional governance (Amable 2003). Capitalist systems are therefore analysed as nation-specific systems of specialized institutions supporting production and income distribution, via market or within-organizations exchange. By a system of specialized institutions, we mean the set of interrelated institutions defining the symmetric set of interrelated incentives faced by individual or collective behaviour in the different sectors of the economic system. Put differently, we consider that an economic system can be typified by the form taken by its institutions and, more importantly, by their pattern of interaction within and across such different socioeconomic sectors as the labour market, production and trade in goods or finance.Footnote 2 Corporations and the state are implicitly accounted for in this analysis as organizations following their own objective, but also as actors of institutional enforcement and change. Corporations organize their activity by defining internal and inter-firm rules, under the shadow of corporate and social law. As for the state, it is the central actor of institutional enforcement, public goods provision and control of violence, with these three elements coalescing to sustain economic development (Besley and Persson 2011).

In the present book, capitalist systems are fundamentally analysed as sets of institutions or regulations reflecting the dominant type of governance of the various sectors,Footnote 3 with the articulation of specialized institutions within and between the different sectors determining the degree of internal consistency and, possibly, the efficiency of the whole system. Patterns of institutional articulation across the different sectors of the capitalist system have, accordingly, received great attention from CC scholars who fundamentally define varieties of capitalism as alternative sets of complementary sectoral institutions. Two institutions are considered as complementary if the presence/efficiency of one increases the returns/efficiency of the other (Hall and Soskice 2001: 17).Footnote 4 Consequently, a particular type of coordination in one sphere of the economy is assumed to develop complementary practices in other spheres as well, with institutional reform in one sector tending to snowball into changes in other sectors (Hall and Soskice 2001; Amable 2003).Footnote 5 One illustration of this could be the partial liberalization of the Chinese goods market. This was first confined to an extraterritorial area because any change towards private property rights and market coordination throughout the whole of China would have led to massive changes in all the other sectoral dimensions. A more ambitious liberalization scheme would have entailed finance shifting towards a more decentralized and thus uncontrolled, mode of organization. Unsurprisingly, the Chinese Communist party’s political resistance to such a complementarity-driven institutional move towards market-based coordination was then so strong that the Party went on to invent a totally original system of economic decision and investment financing decentralization, Town Village Enterprises (TVEs), that allowed the survival of collective property rights and state control over investment and production, two modes of economic governance standing high in the Chinese institutional hierarchy (Xu 2011). Complementarity is thus a mechanism of “reciprocal reinforcement” by which “the existence of one institution provokes that of another, which in turn strengthens the first, and so on” (Crouch et al. 2005: 362).Footnote 6

Institutional complementarity has also been described as a mechanism of functional interdependence by which institutions of certain different sectors affect the outcomes or utility of the whole system (Jackson and Deeg 2006). Studying institutional systems would, therefore, entail addressing mechanisms of systemic causation. In the standard one-dimensional causation mechanism, isolated characteristics in one institutional sector determine specific outcomes in that and the other sectors. In the systemic causation mechanism, it is the clustering of institutions of the different system sectors that generates whole system performance.Footnote 7 For instance, flexible labour markets allocate labour more efficiently when they are articulated with an educative system delivering generic skill formation, while the existence of flexible labour markets increases the relative returns to generic skills. Equally, a deregulated labour market is more efficient in stimulating growth and productivity when it is associated with a deregulated product market and a market-based financing system (Hall and Soskice 2001; Amable 2003).Footnote 8 At the aggregate level at which our work is situated, complementarity therefore implies that one institutional sector’s own mode of regulation is considered in relation to all other sectors and their impact on economic performance has to be assessed at system level. Such systemic causation issues are empirically addressed in Part III of this book, with our different varieties of capitalist systems being characterized and compared according to sets of performance and determinant indicators.

Taken together, institutions that are complementary across the different sectors of the economic system are expected to impact choices and outcomes in a similar direction. However, institutional complementarity does not necessarily imply institutional isomorphism. Put differently, complementary institutions are not necessarily based on a common principle or logic (Aoki 2001; Amable 2003). Excessive focus on institutional isomorphism could even lead institutional comparative analysis to adopt ideal-typical or one-dimensional approaches, thereby neglecting the complex hybridized structure of most real world systems (Crouch et al. 2005). Again, Chinese TVEs provide a good illustration of economic organizations, and their related rules, inspired by a centralized and relation-based political culture (collective ownership), being successfully associated with free market institutions creating incentives to increase productivity (Qian 2003). Such a heterodox hybridization of otherwise rival institutions has effectively produced the incentives ordinarily generated by private property rights, without the institutions of collective property being reformed until recent years.Footnote 9

Now that our main object—capitalist systems defined as sets of complementary institutions—has been clarified, especially in connection with CC literature, it is time to present the general architecture of our empirical approach.

3 The Seven Sectors of Institutional Systems

As explained above, our methodological approach is inspired by a theoretical assumption that is inspired by the CC literature. The CC approach relies on the identification of a set of institutional sectors whose modes of governance and interconnection differ from one country to another. All the institutional domain governance mechanisms coalesce in a more or less complementary fashion, eventually shaping an overall logic of systemic governance. The CC approach generally consists of a priori defining such ideal types of systemic governance, notably by describing their internal institutional complementarity properties.

As shown in Table 3.1, CC generally describes the governance mechanism of each institutional domain by the opposition of two or more ideal-typical models or patterns. These modes are subsequently articulated across the different institutional sectors, thereby forming alternative models of capitalism that are characterized by different types of institutional comparative advantage and economic performance (Hall and Soskice 2001; Amable 2003).

Table 3.2 reports the institutional sectors that we have selected for our comparative analysis of emerging forms of capitalism and the original typologies of sectoral modes of governance that we have identified on our comprehensive sample of 140 OECD, emerging market and developing countries. The institutional sectors that are constitutive of developing countries’ capitalist systems correspond to the five pivotal institutional sectors (labour relations, product market regulation, education and training, social protection and finance) commonly used by CC for studying varieties of mature capitalism (Amable 2003).Footnote 10 Those five dimensions are considered as pivotal sectors of any capitalist system by CC literature as shown by Table 3.1. They cover both production and distribution issues, and they concern both private and public actors. A majority of CC studies have been chiefly concerned by the differences of corporate, inter-firm and industrial relations governance. Even though the labour and product markets are considered as the core sectors of the capitalist system, they are supported by the welfare, education and finance sectors. As for the welfare sector, it subsumes the institutions of welfare states that are related to health, retirement and unemployment transfers, and, in the case of developing countries, the private transfer logic that substitute for a failing welfare state.

The second columns of Tables 3.1 and 3.2 respectively report the main modes of sectoral governance that were identified by CC literature for OECD capitalisms and by our analysis in this book. As shown in the third column of Table 3.2, our representative typology, referring to both developed and developing countries’ capitalisms, fairly differs from those exclusively concerning developed countries. New types of governance have been identified for the two institutional sectors, agriculture and environment, that have been added in our work and are not considered by OECD typologies.

The introduction of two more original dimensions, agriculture and the environment, needs to be justified. Agriculture is still the dominant sector in many developing countries. As explained in Chap. 9, the agricultural sector’s institutions governing land use and contracts between farmers can be very heterogeneous between and often within developing countries. In many developing countries, they still have a crucial influence on livelihoods for a large part of the population because they condition the level and stability of rural incomes. But the institutions governing land ownership and use also influence the political economy of human capital investment and structural change as shown by Galor et al. (2009), with more concentrated land ownership being associated with lower investment in education and subsequent growth. As for the environment, we claim that natural resources are a crucial dimension of developing countries’ socioeconomic systems, insofar as most of them have strong natural resource endowments. Environmental regulations are a crucial source of institutional differentiation since they can be geared, in some developing countries, towards natural resource exploitation, or, conversely, in other countries, towards environmental conservation.

4 Adapting Institutional Complementarity to Developing Countries: De jure and De facto Complementarity

As explained in the two previous sections, the institutional complementarity theory certainly constitutes the theoretical foundation of our empirical research in this book. In opposition with the CC approach of OECD capitalisms, however, we could not start the present study of developing countries’ capitalist systems by a priori defining ideal types based on fully-fledged models of complementarity. As discussed in Chap. 2, there have been too few prior works, either theoretical or empirical, on developing countries’ institutional complementarities that could have informed such an ideal-typical typology. Moreover, dealing with institutional design in developing economies, typically afflicted by policy and market failures, would require a second-best setting in which no institutional form should be condemned as being unable to achieve a socially desired goal or function (Rodrik 2003, 2008). Since many institutional settings might be considered as favourable to economic development, provided they manage to provide the correctly balanced mix of economic incentives and political support needed to ensure expansion of the economic system, we needed to implement an “agnostic” approach. Our characterization of developing countries’ capitalist systems had to rely, therefore, on a flexible notion of complementarity, one which is, in fact, closer to the idea of institutional coalescence. We consider throughout the book that observed sets of coexisting institutions might, in some cases, be self-reinforced because they present elements of complementarity reflected by good economic performance. Rather than starting from a definition a priori of complementary institutions, we have preferred looking at the institutions that tend to be regularly observed together across developing countries. Complementarities, therefore, emerge from the empirical analysis of institutional coalescences, before they can be justified or explained ex post.

Of course, the observed sets of coexisting institutions may also reflect a complex combination of domestic sources of influence, like cultural traits or political critical junctures, and external influence, like colonization or structural adjustment, that could have led to the diffusion of standardized hybrid systems across developing countries. Two types of sectoral governance are not necessarily complementary because they tend to be observed for a sufficiently large number of countries. In fact, they may all be submitted to political economies similarly conducive to this persistent and possibly socially inefficient configuration. Some of them can show signs of efficiency and internal consistency whereas others may finally be inefficient, but persistent because they serve elites’ vested interests. Truly assessing their degree of complementarity would therefore require measuring the average level of economic and social performance of each model, or of each regularly observed institutional configuration. This is precisely what we do in Chap. 12 in Part III.

The general set-up of CC, consisting of defining ideal-types delineated by typical institutional complementarities, needs to be adapted to developing countries, so that the models of emerging capitalism can be generated and characterized, ex post, as the outcome of a prior empirical analysis. More specifically, we argue later in in this book (Chap. 3) that the distinction between de facto and de jure complementarity can be useful in analyzing developing countries’ capitalisms and the a priori undetermined institutional efficiency. We call de jure complementarity the form of complementarity that can be expected on purely theoretical grounds. For example, a flexible labour market is assumed to be complementary to a competitive product market, since product market firms’ entry and exit will be facilitated by higher levels of labour and capital mobility (Hall and Soskice 2001; Amable 2003). Conversely, we define de facto complementarity as forms of institutional efficiency that do not have a priori theoretical justification. This form of complementarity may, instead, appear ex post, with institutions that were not initially supposed to be specifically complementary, delivering unexpected positive effects.

China is the perfect example of a country which has associated market institutions in product markets, and statist forms of regulation in the labour and finance sectors, although the positive development effects of such a heterodox set of institutions cannot be justified by mainstream economic theory. China’s successful economic transition has been explained by the economic incentives delivered by a combination of pro-market (FDI incentives) and statist (collective property) institutions that simultaneously allowed for a massive rise in productive investment as well as the active support of local political elites (Qian 2003). The fundamentally dual nature of the Chinese institutional system, described by Rodrik (2010, 41) as “a market system on top of a heavily regulated state sector”, has exhibited strong de facto complementarities, with this hybrid system proving highly efficient in organizing the transition from a centralized to a capitalist industrialized economy (Lau et al. 2001). China is in no way an isolated case, since Rodrik (2007, 2010: 41) reports similar unconventional institutional configurations for South Korea in the 1960s and 1970s, for Mauritius during the 1970s and 1980s, as well as for India during the 1980s and 1990s.

Conversely, the articulation of the best-fitted institutions supposed to be de jure complementary; that is to say, theoretically complementary, does not necessarily imply that institutional systems work in a fully efficient way. From the mid-eighties to the late nineties, the Washington Consensus set of institutional reforms was seen as an internally coherent policy mix of a first-best type that should rapidly trigger economic growth and restore financial balances. Wholesale reforms, all inspired by the common principle of “getting prices right” on the different markets, were rarely implemented and, when they were, they did not produce the expected economic benefits (Stiglitz 2003; Berr et al. 2009). Neo-institutionalist scholars then came to argue that reform efficiency could be improved by getting governance right (Rodrik 2001). Their theoretical set-up remained, however, strongly inspired by a first-best functionalist logic: each specific and isolated institution is supposed to be designed ex ante to minimize transaction costs for the sake of collective efficiency. Since the functionalist approach considers that each single function or goal should be assumed by only one type of institutional form—the best-fitted one—whatever the national context, conforming all developing countries’ systems to the mix of institutions featured by the institutional frontier, that is the best performing national system in terms of institutional outcomes,Footnote 11 has become a priority goal. The main justification for claiming that one given institutional form or configuration is better fitted than the others has been drawn indifferently from economic theory and from the observation of an international benchmark. According to this de jure approach to institutional fitness of shape, minimum level of enforcement of this best-fitted institution would automatically engender the highest expected economic outcome. Obviously, there would be no room for institutional experimentation of possible de facto complementarities in this context.

Proponents of institutional pragmatism and piecemeal reforms for developing countries have strongly contested this “one best way” vision on several crucial grounds. First, there is huge confusion about the correct set of alleged optimal policies to be implemented by developing countries. Naim (1999) or Rodrik (2006) have, for example, underlined the huge confusion characterizing the theoretical foundations of the Washington Consensus, which has consistently provided developing countries with an allegedly coherent mix of institutional reforms over 20 years. Second, it is difficult for developing countries to use wholesale reforms to set up fully consistent and efficient copycats of mature capitalisms’ institutional systems. This is because very few developing countries have the necessary administrative and legal capacity to implement such a comprehensive set of reforms (Andrews 2013). Equally, by disturbing prevailing sociopolitical equilibria, the institutional reforms required to modify existing institutions and regulations may trigger considerable resistance. Since the observed benefits of the new system may well prove insufficient to balance the heavy social and economic cost raised by the dramatic change in rules, the whole reform process might eventually be rejected.

Hence, even though their institutional components do not seem to be de jure complementary, certain, apparently inconsistent institutional systems may well correspond to efficient institutional systems for the simple reason that they are conducive to socioeconomic development. In this case, we could talk of de facto complementary institutions, in the sense that they are not universally complementary, but locally they are, both in time and space.Footnote 12

Additionally, the long-term persistence of a given institutional configuration does not imply that the system is necessarily de jure or de facto complementary and fully efficient. Nölke and Vliegenthart (2009) contend that the stability of social preferences and path-dependency may constitute a first explanation of long-run institutional persistence of, sometimes inefficient, institutions. They notably report Esping-Andersen (1990) who argue that the variety of post-war welfare state “regimes” was promoted by the then emerging middle classes, which had different values and cultural norms concerning the style and extent of state intervention in social life.Footnote 13 Nölke and Vliegenthart (2009), however, advance a second explanation, particularly appropriate for developing economies. They argue that the existence of self-reinforcing clusters of institutions may cause the persistence of inefficient institutional systems, without abandoning the assumption of complementarity. Institutional externalities may reinforce or contradict one another, thereby generating distinct institutional clusters at equilibrium. Clusters of institutions might, consequently, be rather stable over time and only change very slowly, even though they should have been rejected by rational agents because their socioeconomic efficiency is low.

Hence, a second adaptation of the institutional complementarity theory to developing countries consists in opposing those forms of complementarity that are conducive to economic development and to high-level outcomes, and those that are akin to stable low-level equilibria where strongly consistent institutional systems will maintain poverty. We call the former progressive and the latter regressive complementarities.

As an illustration, some poor countries actually show sets of strongly complementary and self-reinforcing institutions—predatory state, low property rights protection, limited access to judiciary, education and political or economic organizations, repressed finance—that are very similar to the natural state ideal-type described in North et al. (2008) as a typical form of politico-economic system preliminary to modern states. These authors explain how the patron–client political equilibrium typical of the natural state tends to persist in poor countries, even though this stable equilibrium eventually hinders economic development. North et al. (2008) describe natural states as highly consistent and complementary sets of institutions generally showing efficiency in limiting the scope of sociopolitical and economic violence. However, their effect on economic development is less positive, since natural states eventually tend to trap the economy into a persistent low- or intermediary-level equilibrium. Here, de jure stable and consistent institutional configurations may prompt regressive mechanisms strongly adverse to economic development.

Similarly, institutional inconsistencies, that is to say, the persistence, in certain sectors, of institutions that are not complementary to the rest of the system, can be explained by the fact that those institutions have certain positive welfare effects, at least for some social groups. In non-democratic developing countries, even more than in mature democracies, sub-optimal institutional configurations may well survive because they are culturally more acceptable, or because they provide distributive benefits to the dominant sociopolitical coalitions. If slow-moving institutions are often those that are strongly conditioned by culture (Kuran 2011; Roland 2004), they can also persist, independently of their economic consequences, because they serve the interest of dominant sociopolitical coalitions (Acemoglu and Robinson 2006, 2012; Amable 2003).Footnote 14 In this context, some core institutions can reinforce one another in ways that are supportive of the political equilibrium of the system, even though those institutions are inefficient. Schneider (2009), for example, has documented the survival, in Latin America, of an intermediary system, the hierarchical market economy (HME), combining features from the coordinated market economy (CME) and liberal market economy (LME) (for example, externally liberalized economies and highly-regulated and protected labour markets) in an inefficient way, albeit benefitting from the support of strong sociopolitical coalitions. This combination of contradictory regulations has actually introduced strong hierarchical links between and within firms, supported by transnational corporations (TNCs) and big domestic companies. As a consequence, increasing labour market dualism, supported by unionized TNCs and big national companies’ workers, has generated high unemployment levels throughout the Latin American region. De facto institutional complementarities, therefore, could well turn into a regressive process whereby the presence of one institution (labour market rigidity) reinforces the adverse economic effect of another one (external liberalization), whilst also strengthening sociopolitical support for the entire system, however socially suboptimal.

By contrast, some developing countries have, during the last two decades, been busy introducing a high dose of experimentation into their institutional reform-making process (Ahrens and Jünemann 2009). Their institutional sets were neither designed nor implemented to be complementary ex ante. Speaking of developed countries’ institutional systems, Crouch et al. (2005) underline that complementarity is in fact often discovered, ex post, at a later stage in time. A similar observation is made for developing countries by Rodrik (2007, 2010) who speaks of institutional reforms as a process of experimentation of heterodox sets of institutions, with the term “heterodox” suggesting that the observed complementarities are not based on standard theoretical grounds. Country case studies and historical records show that developing countries’ institutional systems articulate sectoral regulations that are the product of multi-layered processes of serendipity, incremental adjustment, politically oriented reforms and globalization-led hybridization. Therefore, observed sectoral institutional arrangements should not be considered as being necessarily the most efficient, but, instead, as the result of a complex and open process of incremental and highly contingent institution building and formalization. Put differently, institutional complementarity is not the outcome of a centralized design but is the result of a constant process of discovery and incremental adjustment that introduces a great deal of slackness in economic system design (Crouch et al. 2005: 363, 366). In his most recent papers, Rodrik (2010) suggests that developing countries might make more intensive use of experimentation to test the institutions and regulations that best match their own national conditions. He even argues that assembling orthodox and unorthodox institutions or regulations, as China has done during the last three decades, has proven efficient to solve incrementally the most binding constraints to economic development. This amounts to saying that setting up systems of non-complementary institutions in the developing countries context may bring about higher social benefits than trying to directly emulate fully complementary Western institutional configurations, like the CME or LME, or else to implement the full package of reforms coined by the Washington Consensus.

Table 3.3 summarizes the argument by combining of de jure and de facto institutional complementarity, on the one side, and their observed economic efficiency, namely whether they are progressive or regressive, on the other side. Each combination is illustrated by examples drawn from the present section.

5 The Original Two-Tier Methodological Approach

Our empirical approach of institutional complementarity is closely connected with that of Amable (2003). We, too, use macro-statistical indicators to first study clusters of institutions at sector level, thereby identifying types of sectoral governance. The difference between our approaches lies at the second stage of identification of capitalist models, since we cluster these sectoral models, whereas Amable (2003) clusters countries across sectors by using individual indicators and introducing each sector one at a time.Footnote 15 The original two-tier methodology we use allows more complexity to be introduced and, accordingly, more variations in the description of the capitalist systems, especially in the case of emerging market economies.Footnote 16

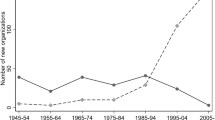

The technical details of our methodology can be found in the Technical Appendix joint to this chapter. The first tier corresponds to the identification of varieties of institutional governance for each of the seven sectors selected to typify capitalist systems: labour, social protection, finance, product market competition, education, agriculture and the environment. These varieties are assessed by a series of quantitative indicators covering the 2006–2010 period that are treated by principal component analysis (PCA) together with mixed clustering techniques that combine hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) with k-means iterations in order to consolidate the initial results. In so doing, we identify, for each of the seven sectors enunciated above, three to five markedly different types of institutional governance. The first output of our work and, incidentally, of Part II is, therefore, the identification, for each country, of a vector of seven types of organization and regulation concerning the labour, competition, social protection, education, finance, agriculture and environment sectors.Footnote 17 As shown in Fig. 3.1, first stage’s final output is made up of 140 country vectors of seven types of sectoral governance.

Some of the sectoral types of governance discussed in Part II, like the bank-oriented type of finance or the liberalized type of competition regime, are rather well known. Others, like the remittance-based informal type of social protection or the export-oriented type of education, are new. The stake, in the second stage of our approach, is to understand how these different sectoral types actually match, at country level, to form singular institutional systems supporting the operation of capitalist markets and organizations. Since all these observed institutional systems govern such typical capitalism attributes as private property, market coordination and labour-capital relationships, they can be considered as good characterizations of the different models of capitalism.

The second tier of our analysis thus consists in clustering the original nominal cross-sectional database made up of 140 country-vectors of seven types of sectoral governance that was generated by the first tier, as described in Fig. 3.1, into a smaller number of capitalist system varieties, by using a mixed classification procedure similar to that used in the first tier of the analysis. More specifically, countries are clustered according to similarities and differences in their set of sectoral institutions. In other words, we study the cross-country associations, across all seven dimensions of analysis and all 140 countries, of the types of sectoral governance that were identified, at the first tier, for each country.Footnote 18 The second-tier of the methodology therefore reduces the extreme diversity in the observed combination of the different sectoral modes of governance into varieties of capitalist socioeconomic systems. Each variety can be characterized by a typical articulation of models of sectoral governance; namely, by a specific pattern of inter-sectoral institutional complementarities.

Hence, each cluster brings together countries showing common traits, which are different from the commonalities observed for the other groups. As we had done for the first tier, and for the same reason, we created a supplementary cluster bringing together countries whose position in the new multidimensional space was not clear-cut because they were either (i) hybrid institutional configurations or (ii) mostly composed of idiosyncratic sectoral institutional types. We named this group of countries the “Hybrid-Idiosyncratic” group. The six identified “models of capitalism” could finally be characterized by their dominant institutional configurations, a mix of the seven sectoral modes of governance.

It is worth insisting that, unlike in some recent attempts by Pryor (2008) or Roland and Jellema (2011) at clustering institutions, complementarities are analysed at the two different levels of analysis in this study. Complementarities are first observed at sector level. In order to first identify the various models of sectoral governance, we analyse how sector-specific individual institutions coalesce for each sector of the whole institutional system. Then, complementarities are investigated at system level, with statistical coalescence between the different types of sectoral governance being considered at a second stage. It is worth emphasizing that this method enables avoiding the identification of false complementarities when all institutional variables are analysed together, without considering complementarities within each sector of the capitalist system. For example, there are no theoretical grounds to believe that the inequality of land holdings is complementary to shareholder rights or the protection of patent rights, as it could be the case in Pryor (2008, 2010) or Roland and Jellema (2011) who cluster individual institutions of different dimensions. Analysing complementarities between the various institutions governing the agricultural sector makes sense insofar as these institutions have been designed and associated to reach common sector-specific goals like securing land ownership or organizing commodity markets.

We contend that institutional complementarities might, therefore, occur at two levels. First, at sector level, the individual institutions governing a given sector of the economy may be more or less complementary and, therefore, may or may not reach sector-related goals. Second, at system level, the different models of sectoral governance may have more or less complementary effects on the whole system aggregate socioeconomic performance. A concentred land ownership may be complementary to limited access to education as shown by Galor et al. (2009). Equally, a rigid regulation of the labour market is likely to be strongly complementary to a heavily state-regulated product market, and weakly complementary to a liberalized financial market.

Insofar as complementarities are assumed to have more relevance across all our seven institutional sectors, this leads us to identify varieties of models of capitalism by observing how the different patterns of sectoral governance coalesce at the system level. Moreover, such an approach to complementarities allows describing each national institutional system as a specific vector of sectoral governance models. We can therefore detect, at country level, complementary institutional patterns, namely, sectoral regulations that show network externalities; as well as regressive institutional configurations, that is to say, sectoral regulations that should not be articulated since they deliver contradictory incentives to economic agents. In both cases, the economic effects of those apparently contradictory institutional patterns are worth being observed, especially when they are positive. In other words, our approach opens the possibility that economically efficient unorthodox patterns of institutional regulation are identified, with important consequences for institutional reform. These variations of the institutional complementarity assumption are further discussed and elaborated in the next section.

6 Politics

Politics has gained increasing consideration in both CC and NIE literature. The latter has tended to restrict its scope to the analysis of the economic effect of alternative political types, like democracy vs. autocracy, presidential regime vs. representative regime (Persson and Tabellini 2003) or extractive vs. inclusive institutions (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012). More interestingly, many typologies of capitalist models in the CC literature implicitly suggest a kind of institutional hierarchy whereby one of the institutional sectors gains analytical superiority over the other complementary sectors, as is the wage–labour nexus in the regulation theory, or the financial domain in more recent analyses of contemporary forms of capitalism. Since agrarian institutions and land ownership concentration are important determinants of economic outcomes, agriculture could well be that dominant domain for the poor agricultural-dependent economies of our sample. Yet emerging industrializing economies, where patterns of institutional change and deeply influenced by modern corporations, are probably characterized to very different hierarchies.

Here, theoretical justifications drawn from political sciences are generally required to explain why one domain might rule over the others. The general premise that institutions are the result of a sociopolitical process shaped by organized vested interests of individual and collective actors rationally seeking to advance their objectives is shared by both these strands of literature (Amable 2003; Acemoglu and Robinson 2012). Institutions are accordingly defined by Amable (2003) as “political economic equilibria” since they reflect both political compromises and functional efficiency. Sociopolitical conflict also organizes institutional hierarchy through the imposition of a priority domain of institutional governance to which the other sectors’ regulation must be submitted (Amable 2013). This view is fairly close to Acemoglu and Robinson (2005) or Bardhan (2005) who stress that institutions are not only designed to solve coordination problems between equal agents with similar interests, but also to solve conflicts among unequal actors with divergent interests.

Although we don’t introduce any form of a priori institutional hierarchy between the seven sectors of our analysis, politics is not totally absent from our study. Although our book is less concerned with political institutions than is the case for those recent contributions, a certain number of political issues are, in fact, addressed.

First, in our work, polity is not considered as a domain by the cluster analysis. We essentially use political characteristics as ex-post characterization variables. This is a crucial difference between our approach and the existing typologies of state capitalism reviewed above. Government and state actions are not viewed as primum movens of actions of economic and social actors. We assume rather that in each society, the state interacts with the other organizational forms of the society through the policy and institution channels. The degree and the nature of state–social organization relationships are specific and conditioned by the particular national context into which they are embedded. They are consequently out of reach for our empirical material and strategy. We only seek to look at the articulation of types of regulation across different socioeconomic sectors and their similarities across countries.

Second, even though our focus is put on economic systems and not on the state, in contrast with Besley and Persson (2011), three out of our six models of emerging capitalism, namely, the Informal (Weak State), Statist (Resource Dependent) and Globalization-Friendly, show clear connections with their Weak State, Redistributive State and Common-interest State models, which are discussed in Chap. 12. Moreover, the political legitimacy and efficiency of the state, as well as its place in the economy, are directly addressed by this book. We show that state interventionism covers a wide spectrum of forms across developing and emerging nations, with those various forms being strongly conditioned by long-term structural determinants. Third, various indicators of political institutions (constraints on executive, judicial checks) have also been analysed as explaining factors of cross-country income differences. We will use various constitutional and political indicators to characterize our models of capitalism by their main political foundations in our socioeconomic models, characterized in Chap. 12. Fourth, Chap. 14 discusses, for a selected sample of countries representative of the different models, the specific political equilibrium that generated each national configuration.

Notes

- 1.

In low income economies with a weak State, the frequent failure of centrally-enforced mechanisms paves the way for the development of more informal governance mechanisms, based on kinship, network and personal relations, as shown by Fafchamps (2004) for Africa, or Jütting et al. (2007) for various dimensions of institutional governance.

- 2.

In line with Pryor (2010), since all the economic policies and their socioeconomic consequences are considered as outcomes of the institutional system, they have not therefore been used in the identification stage of our work. However, once institutional information has been clustered, thereby allowing institutional systems to be clearly identified, outcome variables have been introduced, at a second stage, to further characterize and compare these systems.

- 3.

There is no consensus in CC literature about the exact number of sectors or domains (Jackson and Deeg 2006), even though product market, capital-labor relationships and financial regulation are generally considered as core institutional sectors.

- 4.

More formally, if the difference in utility U(x′)−U(x″) generated by two alternative institutions, x′ and x″, increases for all actors in domain X when z′, rather than z″, prevails in domain Z, and vice-versa, then x′ and z′ (as well as x″ and z”) complement each other, and constitute alternative equilibrium combinations (Aoki 2001). For an extensive survey of the literature on institutional complementarities for OECD countries, see Amable (2003). For an in-depth account of all the notions of institutional complementarity, see Aoki (2001, 2005).

- 5.

For a criticism of this conception, which may have led most CC scholars to adopt a reductionist vision of institutional change, see Becker (2009).

- 6.

- 7.

Pryor (2008, 2010) develop systemic logic even further, claiming that “it is not particular characteristics in domain X that determine any given system in domain Y, and it is not a particular system in domain X that determines any particular characteristic in domain Y. Rather, it is a particular system in domain X that causes a particular system in domain Y” (Pryor 2008: 546). In order to consistently address cumulative causality, he accordingly compares the country composition of institutional clusters with that of economic outcome clusters.

- 8.

- 9.

That system, nevertheless, had to change and adapt when it became progressively inappropriate with respect to the Chinese economy’s changing needs (Xu 2011).

- 10.

There is no such thing as a definitive list of the institutional domains in Comparative Capitalism literature. For example, the role of state’s direct intervention remains subject to debate: has it to be analysed as an institutional domain in its own way, or as a transversal component of the institutional system? By the same token, there is uncertainty as regards the optimal degree of disaggregation within each “domain”, with, for example, institutional domains like labour or education being frequently aggregated into one single institutional dimension (Jackson and Deeg 2006).

- 11.

Thus defined, the institutional frontier is generally the US, and sometimes Switzerland.

- 12.

It is worth remarking that de facto complementarities are implicit in the series of country-case studies brought together in Rodrik (2003). Each of those studies, as Dani Rodrik emphasizes in his introduction to the book, underlines the pragmatic and adaptative nature of the selected developing countries’ trajectories of institutional change during the 1980s and 1990s.

- 13.

- 14.

According to Boyer (2011) institutional persistance is either explained by the higher economic performance induced by the institutional complementarities, or by the sociopolitical process of institutional hierarchy by which an institutional configuration persists because it is favourable to the dominant sociopolitical groups, whatever is its economic efficiency.

- 15.

As already mentioned, an additional difference is that we specifically address emerging forms of capitalism, even though OECD countries are included in our sample.

- 16.

Our approach comes in for the same sort of criticism as many CC typologies, which generally consist in “typologies of typologies”, namely assemblages of institutional domain typologies (Jackson and Deeg 2006).

- 17.

Unlike most CC authors, however, we have chosen not to examine in detail what concerns inter-firm mechanisms of coordination, since they do not make up the essential focus of our analysis. Nor will we systematically analyse the socio-political compromises that support each national variation of capitalism system. Our essential goal is to obtain a picture of the similarities and differences across a large sample of heterogeneous countries in what concerns their socioeconomic institutions and regulations. Although this is done without considering the political economy of each model, political economies will nonetheless be addressed explicitly in Chap. 14 by a comparative analysis of institutional trajectories of a sample of emerging countries.

- 18.

The clustering process consists in identifying the set of groups that minimize intra-group and maximize inter-group heterogeneity. The method assigns to a given group the countries presenting common traits, which also differ from the commonalities observed for the other groups of countries. Two countries exhibiting strictly similar sets of area-related institutional models are clustered together.

- 19.

Note, that in the different dimensions, complete information is available for most countries and that most of the remaining countries only suffer from one single missing variable.

- 20.

The so-called relevant partition, i.e., the relevant number of clusters, is derived from the analysis of the provided dendrogram, and the analysis of two indicators that respectively measure (i) the improvement of the inter- to intra-cluster variance ratio from one given partition to another and (ii) the impact of k-means consolidation on that ratio.

- 21.

More precisely, the standardized Euclidian distance between these countries and the barycentre is below half the median distance.

References

Acemoglu, D., S. Johnson, and J.A. Robinson. 2005. Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-run Growth. In Handbook of Growth Economics, ed. P. Aghion and S. Durlauf, vol. 1A. Amsterdam: Elsevier, North Holland.

Acemoglu, D., and J.A. Robinson. 2006. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2012. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty. London: Profile Books.

Aghion, P., R. Burgess, S.J. Redding, and F. Zilibotti. 2008. The Unequal Effects of Liberalization: Evidence from Dismantling the License Raj in India. American Economic Review 98 (4): 1397–1412.

Ahrens J., and P. Jünemann. 2009. Adaptive Efficiency and Pragmatic Flexibility: Characteristics of Institutional Change in Capitalism, Chinese-Style. PFH Research Papers No. 2009/03, Private University of Applied Sciences, Göttingen.

Amable, B. 2003. The Diversity of Modern Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Andrews, M. 2013. The Limits of Institutional Reform in Development: Changing Rules for Realistic Solutions. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Aoki, M. 2001. Toward a Comparative Institutional Analysis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Aoki, M., and Y. Hayami. 2001. Communities and Markets in Economic Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bardhan, P. 2005. Scarcity, Conflicts and Cooperation: Essays in the Political and Institutional Economics of Development. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Becker, U. 2009. Open Varieties of Capitalism: Continuity, Change and Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Berr, E., F. Combarnous, and E. Rougier. 2009. Too Much Consensus Could be Harmful: Measuring the Implementation of International Financial Institutions Policies and Their Effects on Growth. In Monetary Policies and Financial Stability, ed. Louis-Philippe Rochon. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Besley, T., and T. Persson. 2011. Pillars of Prosperity: The Political Economics of Development Clusters. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Boyer, R. 2011. Diversité et évolution des capitalismes en Amérique latine. De la régulation économique au politique. Revue de la Régulation, 11, 1er semestre.

Crouch, C., W. Streeck, R. Boyer, B. Amable, P.A. Hall, and G. Jackson. 2005. Dialogue on ‘Institutional Complementarity and Political Economy’. Socio-Economic Review 3: 359–382.

Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Polity Press & Princeton University Press.

Fafchamps, M. 2004. Market Institutions and Sub-Saharan Africa: Theory and Evidence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fiori, G., G. Nicoletti, S. Scarpetta, and F. Schiantarelli. 2007. Employment Outcomes and the Interaction Between Product Market Deregulation: Are They Substitutes or Complements? IZA Discussion Paper No. 2770. Bonn: IZA.

Galor, O., O. Moav, and D. Vollrath. 2009. Inequality in Land Ownership, the Emergence of Human Capital Promoting Institutions and the Great Divergence. Review of Economic Studies 76 (1): 143–179.

Greif, A. 2005. Institutions and the Path to the Modern Economy: Lessons from Medieval Trade. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Hall, P.A., and D. Soskice. 2001. An Introduction to Varieties of Capitalism. In Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional of Foundations of Comparative Advantage, ed. P.A. Hall and D. Soskice, 1–68. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jackson, G., and R. Deeg. 2006. How Many Varieties of Capitalism? Comparing the Comparative Institutional Analyses of Capitalist Diversity. MPIfG Discussion Paper No. 06/2.

Jütting, J., D. Drechsler, S. Bartsch, and I. de Soy. 2007. Informal Institutions: How Social Norms Help or Hinder Development, Development Centre Studies. Paris: OECD.

Kuran, T. 2011. The Long Divergence: How Islamic Law Held Back the Middle East. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lau, L.J., Y. Qian, and G. Roland. 2001. Reform without Losers: An Interpretation of China’s Dual-Track Approach to Transition. Journal of Political Economy 108 (1): 120–143.

Milgrom, P., and J. Roberts. 1990. Rationalizability, Learning, and Equilibrium in Games with Strategic Complementarities. Econometrica 58 (6): 1255–1277.

Naim, M. 1999. Fads and Fashions in Economic Reforms: Washington Consensus or Washington Confusion? Working Draft of a Paper Prepared for the IMF Conference on Second Generation Reforms, Washington, DC, October 26.

Nölke, A., and A. Vliegenthart. 2009. Enlarging the Varieties of Capitalism: The Emergence of Dependent Market Economies in East Central Europe. World Politics 61 (4): 970–702.

North, D.C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. New York: Cambridge University Press.

North, D., J.J. Wallis, and B.R. Weingast. 2008. Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorder Human History. Cambridge, MA.: Cambridge University Press.

Persson, T., and G. Tabellini. 2003. The Economic Effect of Constitutions. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Pryor, F.L. 2008. System as a Causal Force. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 67 (3): 545–559.

———. 2010. Capitalism Reassessed. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Pryor, F. 2011. Capitalism and Freedom? Economic Systems 34 (1): 91–110.

Qian, Y. 2003. How Reform Worked in China. In In Search of Prosperity, Analytic Narratives on Economic Growth, ed. D. Rodrik. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rodrik, D. 2001. The Global Governance of Trade as if Development Really Mattered. New York: UNDP.

———. 2003. In Search of Prosperity: Analytic Narratives on Economic Growth. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

———. 2006. Goodbye Washington Consensus, Hello Washington Confusion? A Review of the World Bank’s Economic Growth in the 1990s: Learning from a Decade of Reform. Journal of Economic Literature 44 (4): 973–987.

———. 2007. One Economics, Many Recipes: Globalization, Institutions and Economic Growth. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

———. 2008. Second-Best Institutions. American Economic Review 98 (2): 100–104.

———. 2010. Diagnostics before Prescriptions. Journal of Economic Perspectives 24 (3): 33–44.

Roland, G. 2004. Understanding Institutional Change: Fast-moving and Slow-moving Institutions. Comparative International Development 38 (4): 109–131.

Roland, G., and J. Jellema. 2011. Institutional Clusters and Economic Performances. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 79 (1–2): 108–132.

Schneider, B.R. 2009. Hierarchical Market Economies and Varieties of Capitalism in Latin America. Journal of Latin American Studies 41 (3): 553–575.

Stiglitz, J. 2003. Globalization and Its Discontents. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Topkis, D.M. 1998. Supermodularity and Complementarity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Williamson, O.E. 2000. The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead. Journal of Economic Literature 38: 595–613.

Xu, C. 2011. The Fundamental Institutions of China’s Reforms and Development. Journal of Economic Literature 49 (4): 1076–1151.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Technical Appendix

Technical Appendix

This appendix first describes the methodology implemented within each dimension to explore the multidimensional relations between the collected variables and to establish homogeneous and meaningful clusters of countries from these models of sectoral governance. It then describes how the original nominal database built on the basis of this first set of research findings has been used to identify a small number of capitalist system varieties via a second clusterization procedure.

In the first place, we have compiled the complete required dataset from many institutional and academic sources. Unless otherwise specified, all data used throughout the following chapters are average values over the 2006–2010 period when a number of observations are available or, in a few cases, the single available observation during the period. We have cut down the initial sample of 193 countries by eliminating those with a population of less than a million, and those for which less than 50% of variables were known. This meant that we were able to collect sufficient information for 140 countries and could control for the representativeness of the remaining sample.Footnote 19 Throughout the entire analysis, the possible influence of the remaining missing data has been neutralized by using corresponding mean values.

In the first tier of our analysis, we explore sets of continuous variables that separately describe the different dimensions of our seven fields of interest (labour, competition, social protection, education, finance, agriculture and the environment) using principal component analysis (PCA). The number of variables analysed ranges from 5, for the environment, to 16 for the labour domain, making a total of 81 variables for the seven sectors. In order to back up our PCA results, 25 bootstrap replications of the initial sample were implemented for each dimension to provide confidence intervals for the projected variable coordinates. The information provided by PCA then allowed us to carry out a mixed classification procedure in order to establish homogeneous and meaningful clusters of countries in each domain. Our mixed classification procedure enabled us to conduct hierarchical cluster analysis and to consolidate the relevant partition using k-means-like iterations.Footnote 20

This meant we could identify, for each of the seven dimensions enunciated above, three to five markedly different types of sectoral governance. As such a procedure tended to force each individual into one or other of the identified clusters, we decided to systematically create a supplementary cluster for each dimension (the “idiosyncratic” cluster) in order to account for countries whose position is not particularly clear-cut. This cluster consequently brings together countries whose position in the initial multidimensional scatter of points is close to the barycentre.Footnote 21 Their position is explained by the fact that their sectoral governance type differs from that of clearly classified countries and also differs from that of the other countries present in the “idiosyncratic” cluster. Thus, these countries implement original institutional arrangements that are both (i) different from the “regularities” established for other countries and (ii) mostly different from one another. This “idiosyncratic” cluster is, in other words, that of countries where original institutional arrangements were at work. We obtained an original nominal database in which each country’s national economic system is characterized by a vector of seven types of sectoral governance, one for each of the seven areas used to typify economic systems: labour, social protection, finance, product market competition, education, agriculture and the environment.

In the second tier, we proceeded to a multiple correspondence analysis based on our new nominal database (140 countries, 7 dimensions, 31 types of sectoral governance) to investigate the multidimensional relationships, or regularities, to be observed between the different states of each dimension. Finally, we clustered countries, once again using a mixed classification procedure similar to that of the first tier, in order to identify a small number of capitalist system varieties. Hence, each cluster brings together countries showing common traits, which are different from the commonalities observed for the other groups. As was done for the first tier, and for the same reason, we created a supplementary cluster bringing together countries whose position in the new multidimensional space was not clear-cut because they were either (i) hybrid institutional configurations or (ii) mostly composed of idiosyncratic sectoral institutional types. We named this group of countries the “Hybrid-Idiosyncratic” group. The six identified “models of capitalism” could finally be characterized by their dominant institutional configurations, a mix of the seven sectoral governance types.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Combarnous, F., Rougier, E. (2017). Systems, Institutional Complementarities and Politics: Various Methodological Considerations. In: Rougier, E., Combarnous, F. (eds) The Diversity of Emerging Capitalisms in Developing Countries. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49947-5_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49947-5_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-49946-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-49947-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)