Abstract

Recent questions about the degree to which higher education adequately equips graduates with desired workplace skills has drawn attention to the role of noncognitive skills in college and the workplace. Yet, there is questionable alignment of these skills across higher education and employment sectors. The literature on noncognitive skills, defined here as a diverse set of social emotional and self management competencies, is varied across higher education and employment literatures, thus creating confusion and a lack of clarity. A systematic review of the literature was conducted as a means to clarify and organize a set of terms and concepts that support college and career success. This manuscript presents the findings from that review, as well as the development of a taxonomy created for analytic purposes and alignment of noncognitive skills bridging the higher education and employment literatures. The taxonomy is divided into three domains of noncognitive skills that emerged from our analysis-Approach to Learning/Work, Intrapersonal Skills, and Social Skills.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Higher education

- Employment

- Workforce

- Career

- Non-cognitive

- Soft skills

- 21st century skills

- College success

- Retention

- Persistence

- Motivation

- Self-efficacy

- Social emotional

- Students

- Behaviors

- Success

- Work

- Alignment

A growing body of research demonstrates that noncognitive skills , a diverse set of social emotional and self-management capacities and behaviors , are important predictors of postsecondary and career success (ACT, 2015; Shechtman, DeBarger, Dornsife, Rosier, & Yarnall, 2013). These bodies of scholarship have contributed to a more “holistic picture” of college and career readiness that recognizes the importance of both academic and noncognitive skills (ACT, 2015, p. 4). Indeed, many employers, policymakers, and researchers argue that educators should view the development of noncognitive skills as an integral part of preparing students for future success (Hart Research Associates, 2013; Maguire Associates, Inc., 2012; Moore, Lippman, & Ryberg, 2015; National Research Council [NRC], 2012). Echoing efforts in K-12 education to develop “the ‘whole’ child” (Beesley, Clark, Barker, Germeroth, & Apthorp, 2010, p. 38), colleges have been encouraged to adopt “an integrated approach” that “addresses the social, emotional, and academic needs of students ” (Lotkowski, Robbins, & Noeth, 2004, p. 22).

Yet, while many colleges and universities have long claimed to foster noncognitive skills (Scott, 2006), there is nonetheless concern among employers that students are graduating from college with an underdeveloped set of the noncognitive skills they need to succeed in the workforce (Kyllonen, 2013). For example, an examination of mission statements and stated educational objectives from 23 institutions (Schmitt, 2012) derived a list of 12 commonly used dimensions including leadership, interpersonal skills, adaptability, and perseverance , which are considered by many to be noncognitive. However, despite research on the degree to which these skills are developed among students and growing attention from institutional officials (Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005), some observers contend that college graduates lack workplace readiness skills, thus suggesting they are not leaving higher education “career ready” (Hart Research Associates, 2013). Skills often cited as missing among college graduates include problem solving, adaptability, critical thinking, and communication (Miller & Malandra, 2006; The Conference Board, 2006). Employers’ perception of a lack of career readiness among college graduates suggests a misalignment in the college-to-career pipeline—a misalignment that may be due, in part, to confusion about which skills contribute to college and career success .

There are also challenges in navigating the discourse surrounding these skills, or “personal qualities other than cognitive ability that determine success ” (Duckworth & Yeager, 2015, p. 237), because of the: (1) dizzying array of umbrella terms used to refer to this set of skills, including soft skills , metacognitive skills, 21st century skills , socioemotional competencies, and new basic skills, just to name a few; and (2) lack of clarity about which specific skills are included under these umbrella terms (Conley, 2005; Heckman & Kautz, 2012; Moore et al., 2015; NRC, 2012; Partnership for 21st Century Skills, 2009). This lack of conceptual clarity has been described as “one of the biggest challenges encountered by anyone seeking to make progress in this field” (Shechtman et al., 2013, p. 87). In the discourse of many constituencies, including policymakers, educators, employers, nonprofit foundations, and researchers representing a diverse set of disciplines and fields, the same skill may be described using a variety of different terms and, conversely, a single term may be used to describe skills that are conceptually distinct (Farrington et al., 2012; NRC, 2012; Robbins et al., 2004; Snipes, Fancsali, & Stoker, 2012; Shechtman et al., 2013). This confusion is partly rooted in disagreement about the nature of the skills in question. Although these skills are often described as noncognitive, many object to this term because these skills do, in fact, rely on cognitive processes (Moore et al., 2015). On the other hand, the differences in terms reflect nuances that differentiate them and thus, should be conveyed appropriately.

Some scholars have undertaken efforts to analyze the diverse, disconnected bodies of literature about noncognitive skills , with the goal of developing unifying frameworks or taxonomies that provide a common vocabulary for describing and defining these skills (NRC, 2012; Shechtman et al., 2013). However, existing taxonomies have primarily focused on articulating skills that support academic success in K-12 education (Farrington et al., 2012; Atkins-Burnett, Fernández, Akers, Jacobson, & Smither-Wulsin, 2012; Moore et al., 2015; Snipes et al., 2012). Existing frameworks neither apply to higher education , nor do they achieve the important task of bridging the interrelated contexts of higher education and employment . As a result, there is a need for greater clarity and organization with respect to noncognitive skills as they relate to college and career success , and how such skills can most effectively be developed (NRC, 2012; Shechtman et al., 2013; Snipes et al., 2012).

In this chapter, we describe the ways in which higher education and employment literatures portray the noncognitive skills believed to support success in college and career . Synthesizing research findings from multiple disciplinary traditions is a first step toward providing a common vocabulary for the diverse constituencies engaged in this discourse, and may support more intentional programming and teaching by those interested in improving the educational and career transitions and outcomes of emerging adults (Snipes et al., 2012). Analytically, we sought to identify the commonalities that otherwise are lost in a sea of terms and differing contexts. With full awareness that any attempt to categorize or align terms across two sectors runs the risk of reducing the meaning and nuance of terms, this chapter includes the development of an organizing taxonomy that was primarily used for analytical purposes, but which we see as a promising a cross-sector framework. Drawing on two decades of multi-disciplinary research, this chapter uses the term noncognitive skills to refer to the range of behaviors , mindsets, and developmental skills prior research argues is conducive to college and career success . Aware of the ongoing debate about the best term to describe skills that we believe are, indeed, cognitive, we made a deliberate choice to use a term that is widely understood today despite its shortcomings. The primary aim of this chapter is to propose an aligned framework to guide future research and applied practice that moves away from conceptually vague or composite terms and towards clarified terms and meanings behind important college success and career readiness skills.

The Importance of Noncognitive Skills for College Success

Academic success in college requires that students regularly draw on a range of skills, behaviors and mindsets that lead to learning and engagement. Studies show that, after accounting for academic ability, noncognitive skills including academic self-confidence, motivational factors, and time management help predict college students ’ persistence and academic performance (Lotkowski et al., 2004; Person, Baumgartner, Hallgren, & Santos, 2014; Robbins et al., 2004; Robbins, Allen, Casillas, Peterson, & Le, 2006). Indeed, the role of noncognitive variables in college readiness and success has been a focus of research since the 1970s, specifically as a predictor of college achievement. In one longitudinal study, for example, Willingham (1985) found that while the traditional academic predictors of high school rank and admissions test score best predicted scholastic types of college achievement, supplementary admissions information that captured students ’ noncognitive skills (e.g., the personal statement, letters of reference) better predicted success in other areas such as elected leadership and scientific or artistic achievement.

In related work, Sedlacek and Brooks (1976) drew upon available research to develop a list of seven noncognitive variables that they argued were related to academic success for all students and minority students in particular. Tracey and Sedlacek (1984) designed the Non-Cognitive Questionnaire (NCQ) to assess these variables, and the NCQ has since been expanded to assess a total of eight variables: “positive self-concept”; “realistic self-appraisal”; “understands and knows how to handle racism: navigating the system”; “long-range goals”; “strong support person”; “leadership”; “community”; and “nontraditional knowledge acquired” (Sedlacek, 2011, pp. 190–193). Over time, researchers have tested the predictive validity of the NCQ across a variety of student populations (Adebayo, 2008; Ancis & Sedlacek, 1997; Arbona & Novy, 1990; Boyer & Sedlacek, 1988; Sedlacek & Adams-Gaston, 1992; Tracey & Sedlacek, 1985, 1987, 1989; White & Sedlacek, 1986) and college settings (Nasim, Roberts, Harrell, & Young, 2005; Noonan, Sedlacek, & Veerasamy, 2005), with varying results. In many cases the NCQ was a positive predictor of persistence (Tracey & Sedlacek, 1985, 1987), and GPA (e.g., Adebayo, 2008, Sedlacek & Adams-Gaston, 1992; Tracey & Sedlacek, 1985), particularly for underrepresented populations on campus. There is widespread use of the NCQ in research settings, the college admissions process (Sedlacek, 2004), and the selection of Gates Millennium Scholars (Ramsey, 2008; Sedlacek, 2011).

While the NCQ is widely used, the instrument’s psychometric properties have been criticized. Thomas, Kuncel and Credé (2007) conducted a meta-analytic review of studies using the NCQ to examine the predictive validity of NCQ scores and examine the extent to which race and gender had a moderating effect on the validity of NCQ scores. Based on their analyses, the researchers concluded that NCQ scores “are largely unrelated to college performance as measured by GPA, college persistence , and credits earned” (Thomas et al., 2007, p. 648) and advised against using the NCQ for admissions decisions. Thomas et al. do note that it is the way the constructs are operationalized, without strong internal consistency, rather than the unimportance of these noncognitive constructs. King and Bowman (2006) also highlight psychometric flaws in the NCQ such as misalignment of questionnaire items and constructs that call into question some of the positive findings of research using this instrument.

Other researchers also found mixed results when examining the relationship between noncognitive skills and college student success . In a 2004 meta-analysis of 109 studies, some of which utilized the NCQ, Robbins et al. (2004) examined the relationship between noncognitive factors and college performance and persistence and found that while most of the noncognitive factors they tested correlated positively with retention , the relationships between these skills and performance were not as strong. In spite of this finding, Robbins et al. (2006) later explored the role that noncognitive factors play in predicting academic performance and retention among first-year students at two- and four-year institutions and found, consistent with prior studies (Busato, Prins, Elshout, & Hamaker, 2000; Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2003), that academic discipline, which they defined as effort and conscientiousness with respect to schoolwork, was the top predictor of academic performance and one of two top predictors of retention , followed by general determination, which was predictive of performance and positively related to retention . A meta-analysis of the relationship between noncognitive factors and academic performance (Poropat, 2009) reported similar findings. The analysis used the five-factor model of personality, commonly used by psychologists to assess personalities, as a framework for analyzing 80 studies. Among the five factors of agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, extraversion, and openness, Poropat (2009) showed that only conscientiousness was strongly associated with college academic performance when analyses controlled for high school academic performance.

Scholars have also examined the particular impact of specific noncognitive factors related to college success . Richardson, Abraham, and Bond (2012), for example, reviewed 13 years of research into predictors of students ’ grade point averages (GPAs). Their findings were consistent with those of Robbins et al. (2004), Poropat (2009) and others (Conard, 2006; O’Connor & Paunonen, 2007; Trapmann, Hell, Hirn, & Schuler, 2007) with regard to conscientiousness, but also highlighted the influence of additional noncognitive skills such as performance self-efficacy and emotional intelligence. Similarly, Schmitt et al. (2009) found that noncognitive measures in the form of biodata and situational judgment (e.g., interpersonal skills, adaptability and life skills, perseverance ) added incrementally to the prediction of college GPA, and in a study of students ’ academic performance during the first two years of college, Shivpuri, Schmitt, Oswald, and Kim (2006) found that noncognitive factors predicted initial academic success as well as the extent to which students ’ academic performance changed over time.

The Importance of Noncognitive Skills for Career Success

Just as researchers have focused on the relationship between noncognitive skills and college success , they have also examined the role of noncognitive skills in career success (Cunha & Heckman, 2010; Heckman & Kautz, 2012; Kyllonen, 2013; Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007). Career success has been defined in both extrinsic (e.g., salary, promotions) and intrinsic (e.g., job satisfaction ) terms (Seibert & Kraimer, 2001), and research from the past 25 years has supported early hypotheses (Bowles & Gintis, 1976) that noncognitive behaviors and traits, rather than cognitive skills, have a far greater effect on labor market success (Bowles & Gintis, 2002; Farkas, 2003). Further, a summary of meta-analyses (Ones, Dilchert, Viswesvaran, & Judge, 2007) examined the relationships between the five-factor model and several variables related to career success including performance criteria, leadership criteria, team performance, and work motivation , and its authors concurred with Murphy and Shiarella (1997), who determined that “there is considerable evidence that both general cognitive ability and broad personality traits (e.g., conscientiousness) are relevant to predicting success in a wide variety of jobs” (p. 825).

According to Ng & Feldman (2010) there is a strong relationship between noncognitive skills , educational success , and career success . Their meta-analysis showed that work experience and investments in education enhance cognitive ability and conscientiousness, which affect professional performance. Stronger performance in the workplace, in turn, results in career success in the form of higher salary levels and more promotions (Ng & Feldman, 2010). Indeed, surveys show that employers across diverse industries value noncognitive skills , as they report seeking job candidates who can collaborate effectively with teams, approach work in a planful and organized way, and communicate skillfully (Hart Research Associates, 2013; National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2015). For example, in its annual national survey of employers, the National Association of Colleges and Employers (2015) found that over 80 % of respondents seek evidence of leadership skills when reviewing the credentials of new college graduates. Likewise, another study (Finch, Hamilton, Baldwin, & Zehner, 2013) found that when employers were asked to identify and rank the competencies they sought among new college graduates, all of the highest ranked skills were noncognitive.

However, according to Bowles, Gintis, & Osborne (2001) the link between noncognitive skills and career success may not be as straightforward as it appears. Earnings-enhancing behaviors may be learned from parents, fostered by “more or higher quality schooling,” (Bowles et al., p. 42) or signaled by additional years of education. In addition, other studies have shown that career success is, in part, a function of receiving supervisor support and opportunities for skill development (Eby, Butts, & Lockwood, 2003; Ng, Eby, Sorensen, & Feldman, 2005) as well as participation and performance in organizational workgroups (e.g., departments, working teams, professional networks) (Eby et al., 2003; Van der Heijde & Van der Heijden, 2006). Thus, education may provide some of the cognitive skills required for participation in the labor market, but less is understood about why noncognitive skills so strongly impact outcomes beyond college (Levin, 2012).

In a critique of the discourse on employer-desired skills, Urciuoli (2008) argued that noncognitive skills in particular.

…establish the type of person valued by the privileged system in ways that seem natural and logical…[and] represent a blurring of lines between self and work by making one rethink and transform one’s self to best fit one’s job, which is highly valued in an economy increasingly oriented toward information and service (p. 215).

Similarly, Grugulis and Vincent (2009) argue that due to the difficulties associated with evaluating noncognitive skills , the proxies that employers use for these skills “may support and legitimize discrimination” based on assumptions related to behavioral norms associated with gender or race (p. 599). Further, they write, noncognitive skills “exist largely in the eye of the beholder and can advantage employees only when noticed, authorized, or legitimized by their employers” (Grugulis & Vincent, 2009, p. 611). Research on executives, for example, shows that conscientiousness and agreeableness are negatively related to career success (Boudreau, Boswell, & Judge, 2001), suggesting that the noncognitive skills desired by employers of more junior employees may not be the same as those desired from senior-level employees. These critiques raise questions about the relatively subjective value employers place on noncognitive skills and further suggest that some workplace readiness skill development needs to take place prior to job placement.

Gap in Career Readiness of College Graduates

Concerns expressed in the current debate about career readiness are driven by research on the discrepancy between the skills acquired through education and the skills required for jobs (Evers & Rush, 1996). Robst (2007), for example, analyzed national data and found that 45 % of workers reported that their job was either partially related or unrelated, or “mismatched,” to their field of study (p. 397). Robst (2007) also found that mismatched workers earned less than “matched” workers with an equal amount of schooling. Indeed, employers report that recent college graduates lack important noncognitive skills including adaptability, leadership, time management, and communication (Harris Interactive, 2013; Maguire Associates, Inc., 2012; Miller & Malandra, 2006; The Conference Board, 2006; Stevens, 2005; Tanyel, Mitchell, & McAlum, 1999).

The overwhelming consensus among employers that graduates lack important career -ready skills sent a strong message to higher education to address this skills gap. Indeed, many institutions of higher education have implemented programs and curricula designed to cultivate noncognitive skills (Bembenutty, 2009; Fallows & Steven, 2000; Navarro, 2012; Savitz-Romer, Rowan-Kenyon, & Fancsali, 2015; Shechtman et al., 2013). Moreover, these concerns have inspired graduates to seek out additional post-graduation training in order to further develop skills needed in the workplace (Arthur, Bennett, Edens, & Bell, 2003; Sleap & Reed, 2006) and spurred the creation of private “bridge” programs designed to fill the college-to-career transition gap (Grasgreen, 2014). This perceived lack of alignment foregrounds this study.

Methods

The gap in career readiness and the development of programs designed to bridge that gap inspired the larger project within which our study is situated. This study used a systematic review process to analyze relevant scholarly literature from the fields of higher education and employment with the goal of exploring and describing mis/alignment in how these two bodies of literature represent noncognitive skills . We anticipated that doing so would serve as a first step towards creating better alignment and clarity. Specifically, the following questions guided our systematic review and analysis:

-

1.

How does the literature from the fields of higher education and employment describe the noncognitive skills regarded as important for success in college and career ?

-

2.

Comparing these two bodies of literature, how are their representations of noncognitive skills similar? How do they differ?

To answer these research questions, we utilized a systematic review , as this process allowed us to answer these research questions using a protocol or “systematic and explicit methods to identify, select, and critically appraise relevant research” (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, The PRISMA Group 2009, ¶4). We elected to use this format rather than a meta-analysis due to the multiple types of publications addressing noncognitive skills and the limited number of empirical studies in the employment literature. Further, a systematic review served our primary research purpose, which was to identify themes in the literature that may promote greater understanding of the specific issue of concern, notably the lack of alignment between higher education and employers. Although there is not yet widespread consensus on the exact set of skills that constitute noncognitive skills , or agreement on the best term to be used to describe these types of skills, we believe that a systematic review of this nature will lead to greater clarity of understanding, increased usage, and assessment of these skills. Members of the research team, which included two faculty co-principal investigators, two postdoctoral research assistants, and two doctoral student research assistants, participated in the review of existing literature related to noncognitive skill development related to college success and career readiness. We utilized a three-step process to complete this scan and analysis: source identification, source review, and skill analysis.

Source Identification

During the source identification process, team members generated a list of keywords related to noncognitive skills (e.g., soft skills , academic mindset, twenty-first century skills /learning , social emotional factors), to search six academic databases (EBSCO, Business Source Complete, ABI Inform, Google Scholar, ProQuest, and Psych Info), the internet, and an academic library catalog. The search process yielded 2097 sources. In order to focus on the articles with the most relevance, we reduced the scope of literature to be reviewed by applying criteria including: research published between 2000 and 2013; manuscripts focused on noncognitive skill development in undergraduate education or during employment ; U.S.-focused studies; and a preference for those manuscripts focused on implementing a specific intervention. Applying these criteria, the team excluded 1854 sources based on abstract review and reviewed 243 at the full text level. An additional 55 sources were excluded during the full text review for not meeting the above criteria. The research team made the decision to include non-empirical sources in our review based on our focus on skills and terminology definitions, and the sources chosen provided insight into how constituents in each domain described and engaged with the skills.

In total, the source identification process yielded 188 usable sources, including 145 higher education sources and 43 employment sources (Table 4.1). Of the 145 higher education sources, 123 were empirical studies and 22 were non-empirical pieces that included conceptual reviews, case studies, and literature reviews. The employment literature was more evenly divided between empirical and non-empirical work with 27 empirical pieces that were primarily quantitatively focused and 16 pieces that were often reviews of the literature or conceptual reviews. Within the non-empirical category, the employment literature contained proportionately more literature reviews (nine sources) and essays or op-eds (three sources) than specific case studies or general strategies for how employers can cultivate the desired skills in their employees (four sources). By contrast, in the higher education literature, 11 out of the 22 non-empirical sources presented case studies, curricula, or policies for developing noncognitive skills in students . These differing emphases on concrete examples continued in the empirical sources, with the higher education literature featuring six studies on curricular interventions, while only one source in the employment literature assessed the effectiveness of a training program (Table 4.1).

Source Review

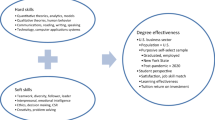

Systematic reviews utilize a disciplined approach to reviewing articles to guide the analytic process. Thus, the research team developed a rubric that provided a systematic structure for each source to be reviewed. Rubric categories included: noncognitive skill definitions; related noncognitive domains; specific study methods used; study outcomes; the context of the institution or employer type; and the population of focus. Due to the size of the rubric, it is not included in this chapter. The rubric allowed for an individual skill or term to be entered into an Excel database, thus allowing a skill to be considered as the unit of analysis. For example, as illustrated in Fig. 4.1, if a single source examined multiple noncognitive skills within the context of a single noncognitive domain, each skill was entered and analyzed separately into the rubric.

To test the efficacy of the rubric, all six team members reviewed the same three sources and compared their rubric entries. The four research assistants then reviewed over 50 sources each, and rubric entries were subsequently reviewed by one of the primary researchers. The source review process led to over 1140 rubric entries. While we were liberal in including skills in the rubric, we made the decision to exclude technology skills (e.g., computer literacy) and industry specific skills (e.g., business acumen, numeracy) as they were outside the scope of this project.

Skill Analysis Review

In the skill analysis stage, the research team members analyzed the data collected using the rubric, as well as field notes recorded during the source review process. To achieve our goal of identifying whether there is alignment between the noncognitive skills represented in higher education and employment literatures, the primary analytic process consisted of grouping the 1140 rubric entries along with definitions located in the literature. Using a skill and definition as our unit of analysis, members of the research team conducted a sorting exercise to move from those individually delineated skill/definition pairings to larger categorical groupings to develop a framework (Chinn & Kramer, 1999). All terms were also coded as either higher education or employer, to examine similarities and differences in the language and distribution of terms between the two bodies of literature. This framework took shape as a taxonomy that was used as a tool for our skill analysis. Although there are pre-existing taxonomies that focus on articulating skills that support academic success in K-12 education (Atkins-Burnett et al., 2012; Farrington et al., 2012; Snipes et al., 2012) and skills that support academic and early career success in young adulthood (Nagaoka, Farrington, Ehrlich & Heath, 2015), we did not find a taxonomy that allowed for a cross-sector review of alignment between higher education and employment , and thus, coded the terms in the literature to create a taxonomy.

The analytic method began with a process of qualitatively coding the data, using an inductive approach. With a focus on terms and definitions, we nested terms together to reduce our number of skills for analytic purposes. In this way, we refer to three types of terms that were located in the literature. First, we identified verbatim terms, which described skills in a way that clearly represented their meaning (e.g., communication skills). Second, we nested terms, which included terms that were defined in a way that matched a verbatim skill and we recoded these terms as the verbatim skill they matched (e.g, teamwork skills were recoded as collaboration). Third, we used representative terms, which were the terms we used to represent a set of nested terms for which there was not an appropriate verbatim skill in the literature (e.g., attention control represented terms such as effort control, focus, and concentration). To illustrate the relationship between these terms, see Fig. 4.2. The nesting process relied on the use of definitions we extracted from the sources. Through multiple iterations, we identified patterns, groupings of terms or definitions that seemed to be described similarly.

Through this inductive process, we developed an organizing taxonomy of noncognitive skills that is grounded in the literature from these two fields. Each skill in our taxonomy represents one of the groupings of terms/definitions that we identified through the coding process. We further developed a definition for each skill in our taxonomy, based on the definitions from the grouping, and noted alternative terms. Thus, our categories were derived from the data (Elo & Kyngas, 2008). Finally, the research team identified primary themes (Dey, 1993), noting consistency of terms and definitions and the types of terms used in the publications . As a result of this process, approximately 300 skills are not reflected in our taxonomy. Some terms were excluded from the taxonomy for the following reasons: a term was too broad to fit into one of our groupings (e.g., learning styles, personal traits), did not include a definition that allowed us to interpret the meaning of the named skill (e.g., testing skills), or was beyond the scope of our work (e.g., critical thinking, spirituality, social desirability, technological competence).

The process described above was specifically utilized to answer our first research question—regarding how the higher education and employment literatures describe the noncognitive skills viewed as important for college and career success –and included the inductive process of looking at trends in skill representation, noting high and low frequency terms and trends in the literature. Our research team also conducted a comparative analysis to examine similarities and differences in skills, definitions, and conceptualizations of noncogntive skills, in order to answer our second research question regarding mis/alignment between higher education and employment sectors.

Limitations, Delimitations and Trustworthiness

There are several limitations to our work. While we drew on literature from both education and employment sources, the majority of the articles we reviewed were empirical in nature and focused on higher education . This may have been due in part to the fact that, as academics within the field of higher education , we searched databases that likely privilege higher education articles . In addition, since we chose to include empirical and non-empirical work, there were some challenges related to comparisons; however, the team elected to prioritize the specific skill rather than the method of analysis. This choice seemed the most inclusive way to account for the multiple terminologies used in a range of sources focused on noncognitive skills and behaviors .

We did not intend to examine each of the individual skills, as this work has been done by others (Crede & Kuncel, 2008; McAbee & Oswald, 2013; O’Connor & Paunonen, 2007; Trapmann et al., 2007). Rather, the primary purpose of our study was to determine the range of noncognitive skills represented in publications and examine where these skills align and diverge between the higher education and employment literatures.

Finally, we ensured trustworthiness by utilizing several strategies. Our six-person research team brought multiple perspectives to our analyses (Creswell, 2014). With multiple team members, each person served as an auditor of our work to check interpretations of our taxonomy and additional findings. We have also shared our findings with educational researchers who were not a part of our study to solicit additional feedback about the meaning we attributed to the terms.

Findings

Our analysis revealed several trends in how noncognitive skills are described in relevant literature from the fields of higher education and employment , both collectively and respectively. In the following section, we describe four key findings: variation in terms and definitions used to describe noncognitive skills ; commonalities among terms that we organized into a taxonomy of noncognitive skills that spans the higher education and employment literatures; differences in the noncognitive skills emphasized by the higher education and employment literatures; and differences in how these two bodies of literature describe noncognitive skills .

Variation in Terms and Definitions Used to Describe Noncognitive Skills

Our review of 188 sources from the higher education and employment literature yielded 1140 rubric entries that capture how sources’ authors described the noncognitive skills that they framed as important for college and career success . Further analysis of those rubric entries revealed a great deal of variability in the terms these sources used to describe noncognitive skills : we found 509 distinct terms. There was very little overlap in verbatim terms between the higher education and employment literatures, with only 17 of these verbatim terms appearing in both bodies of literature. Three-hundred and forty-nine terms were exclusive to the higher education literature while 143 terms were unique to the employment literature.

The most frequently used verbatim term across both sectors, with 15 occurrences, was self-efficacy , grounded in the work of Bandura (1977), and defined by Yang and Taylor (2013) as “the perception of one’s own ability or capability in performing a task” (p. 654). Beyond those occurrences of self-efficacy per se, we also found 12 different, but similar, nested terms that include the word “self-efficacy ,” such as academic self-efficacy and self-efficacy for writing. These similar terms were used in 18 additional sources, bringing the total number of occurrences of self-efficacy up to 33. Other frequently occurring representative terms included conscientiousness—defined by Komarraju and Karau (2005) as “being organized, purposeful, and self-controlled” (p. 561)—which occurred in 11 sources, and time management—defined by Bembenutty (2009) as “estimating and budgeting time” (p. 615)—which occurred in 10 sources; three additional sources also used terms similar to time management, such as time and study environment management.

The relatively high frequency of these terms stands in contrast to the vast majority of the terms used to represent noncognitive skills in the literature we analyzed, as more than 80 % of the terms we found occurred in only one source. For example, the vast majority—300 of 366—of the higher education terms occurred in only one source. Among these unique terms were action control, defined by Ganguly, Kulkarni, and Gupta (2013) as the “intuitive ability to regulate one’s feelings and thoughts” (p. 256); self-consequating, defined by Wolters and Benzon (2013) as students ’ “use of self-provided rewards for pushing themselves to complete their coursework” (p. 209); and general determination, defined by Le, Casillas, Robbins, and Langley (2005) as “the extent to which students are dutiful, careful, and dependable” (p. 494).

In addition to this variability in the terms used to describe noncognitive skills , we also found that the sources we analyzed defined noncognitive skills using three different approaches. While some sources provided explicit conceptual definitions for skills, such as those we cite above, other sources provided operational definitions for skills, most often by citing items from instruments designed to measure those skills. For example, Strage et al. (2002) operationally defined time management using items from a scale they designed to measure this skill in college students ; items included frequency of needing an extension, frequency of completing readings before class, and the number of hours per week spent studying. These different approaches to defining noncognitive skills meant that we found a great deal of idiosyncrasy—and very little overlap—in how our sources defined these skills. In addition to sources that provided conceptual or operational definitions of noncognitive skills , we also found that many of our sources—particularly those from the employment literature—did not provide any type of definition for the skills they described. For instance, Macarthur and Phillippakos (2013) did not define time management, so it was unclear if they were using the concept of time management in the same way as other researchers who provided conceptual definitions for time management.

A Taxonomy of Noncognitive Skills Spanning Higher Education and Employment Literature

Although we found a great deal of variation, we also found underlying patterns in terms and definitions that enabled us to develop an organizing taxonomy of the noncognitive skills that our sources framed as important for college and career success . Through our process of coding and nesting rubric entries, we condensed 757 of the original 1140 entries into 509 unique terms that we then grouped into 42 categories, each representing a noncognitive skill that spans the higher education and employment literature. These 42 skills, listed in Table 4.2, formed the content of our taxonomy, which we created as a tool to explore alignment across the two bodies of literature. The Appendix provides sample definition(s) and synonyms for terms that had multiple definitions, or in cases when the term itself lacked clear meaning, as a way to both illustrate our process and highlight the diversity of terms and definitions that are used in these bodies of literature to describe skills that we view as conceptually coherent.

After we organized the rubric entries into the 44 skills that constitute our taxonomy, we noticed commonalities across skills that suggested they could be further grouped into domains of related skills. Specifically, we identified three domains, each with a different “locus” or target point of the skills: were the skills directed at a particular task, inwardly toward the self, or toward other people? This schema formed the basis for our three domains: Approach to Learning/Work , Intrapersonal Skills, and Social Skills.

Approach to Learning/Work

The Approach to Learning/Work domain comprises 15 representative skills that individuals use to engage in tasks required to be successful in school or work. Examples of representative skills from our taxonomy that we included in this domain are attention control, metacognition , growth mindset , goal orientation and goal commitment. This domain was ultimately defined by its focus on behaviors , skills, and dispositions that individuals use to engage in work or study. The terms categorized in this domain ranged from beliefs and values that help individuals approach and complete a task, to the control/management of internal and external processes and resources in the service of accomplishing a task. Being able to define a task, set long- and short-term goals related to that task, and organize oneself appropriately to produce quality work in completing the task were the salient themes underlying this domain. Studies that were part of our rubric demonstrated, for example, that in order to learn effectively, individuals must devote sustained attention to learning tasks (Zimmerman, 2001). Such attention control requires self-regulation, the process through which learners “transform their mental abilities” into skills related to specific tasks (Zimmerman, 2001, p. 1).

Intrapersonal Skills

The Intrapersonal Skills domain includes 17 representative skills residing within the individual that influence behaviors and judgments about oneself. Examples of representative skills in this domain include self-efficacy , openness, adaptability, conscientiousness, and self-awareness. Although a clear conceptual pathway exists between many of these Intrapersonal Skills and the ultimate outcome of a task (e.g. the type of work ethic and attention to detail reflected in the skill of conscientiousness obviously might impact the quality of work produced), this domain differs from Approach to Learning/Work in that the skills in this domain are first and foremost directed at the individual self rather than an appointed task. In other words, any impact of these skills on an external task is mediated by the internal impact on oneself. The distinction may seem minor but holds important implications for any attempt at intervention or development of these skills compared to those in Approach to Learning/Work; thus, it was important to us to distinguish these skills as a separate domain.

Social Skills

Social Skills, the final domain in our taxonomy, consists of 12 representative skills that reflect an individual’s ability to successfully engage with others around them. Examples of skills in this category include empathy, belonging, and cultural awareness. As previously observed, conceptual pathways exist between Social Skills and the other two domains, Approaches to Learning/Work and Intrapersonal Skills. Many intrapersonal skills also impact one’s ability to interact with others, and many social skills impact the quality of work produced in a collaborative environment. However, the Social Skills domain is distinct from the others in that the presence of other people and an expectation of social interaction are prerequisites for the manifestation of any of the skills categorized in this domain. And, as previously noted, we assigned terms to a particular domain based on the primary locus or first point of contact for the skills in question.

Higher Education and Employment Literature Focus on Different Noncognitive Skills

Developing a taxonomy of noncognitive skills that is grounded in relevant literature from both the higher education and employment literatures provided us with a framework for comparing the relative emphases, across two bodies of literature, on specific noncognitive skills and on domains of related skills. Our comparative analysis revealed striking differences in saturation of research on noncognitive skills in the higher education and employment literatures, respectively.

To begin, the skills in Approach to Learning/Work were largely derived from the higher education literature as opposed to the employment literature. Table 4.3 illustrates that 41 % of all rubric entries from higher education literature were placed in this domain. In comparison, only 15 % of the noncognitive skills from the employment literature were nested in this domain. Ultimately, the higher education literature contributed 165 unique terms nested into 15 skills, while the employment literature contributed just 19 unique terms into eight of the 15 total skills in this domain. Furthermore, there were few similarities among high frequency skills between the higher education literature and the employment literature in this particular domain. For example, in the higher education literature goal orientation (17 %) was the most frequently mentioned skill within this domain, followed by study skills (10 %), attention control (9 %), and commitment to achieving goals (9 %). In contrast, the employment literature revealed a different concentration of skills within the domain, such as identification of obstacles and strategies (29 %), managing time (21 %) and organization skills (15 %).

We discovered slightly more balance of skill representation by sector in the Intrapersonal domain. Approximately 36 % of all rubric entries in both the higher education and employment literatures were nested in the Intrapersonal domain (Table 4.3), and our rubric showed greater overlap in high frequency skills between the two bodies of literature in this domain compared to Approach to Learning/Work . However, the types of skills emphasized by each sector were still different. As previously mentioned, the most frequent term found in the higher education literature, across all three domains, was self-efficacy , which accounted for 26 % of the nested terms within the Intrapersonal domain, with conscientiousness representing 11 % of the nested terms in this domain. When examining the employment literature, terms were more dispersed across the domain, with taking initiative (12 %), conscientiousness (11 %), self-efficacy (11 %), and adaptability (10 %) the most frequently cited skills. Three skills appeared in the higher education literature that were not represented in the employment literature: developing strong personal values, self-concept, and understanding institutional/academic expectations.

Representation by sector in the Social Skills domain is nearly the inverse of that in the Approach to Learning/Work domain. Only 23 % of rubric entries in the higher education literature were ultimately nested in this domain, compared to 48 % of rubric entries in the employment literature (Table 4.2). However, due to the fact that we have many more rubric entries for the higher education literature, the number of unique terms within each body of literature was relatively similar, with higher education literature contributing 75 unique terms and employment literature contributing 81 unique terms.

The Social Skills domain reflected the most alignment in high-frequency skills in our rubric across the two sectors. Social skills (the skill set that ultimately lent its name to the overall domain) was the highest frequency skill in this domain in both bodies of literature. Other examples of alignment of high-frequency skills in this domain include communication (35 % of rubric entries from higher education and 30 % of rubric entries from employment ) and collaborative skills (32 % from higher education and 29 % from employment ).

Variations in Defining Skills Across Sectors

When the research team compared the two bodies of literature, notable patterns emerged. Specifically, we noticed differences in the kinds of terms used by each body of literature to describe noncognitive skills . Perhaps because of its stronger empirical base and roots in human development and psychology, the higher education literature was more likely to describe specific verbatim skills such as self-efficacy (e.g., Navarro, 2012; Putwain, Sander, & Larkin, 2013) and mastery orientation (e.g., Corker & Oswald, 2012; Strage et al., 2002; Yang & Taylor, 2013). In contrast, we noticed that the employment literature often used more general or vague verbatim terms, such as soft skills (e.g. Blaszczynski & Green, 2012; Davis & Woodward, 2006; Grugulis & Vincent, 2009; Hoffman, 2007; Kavas, 2013; Kyllonen, 2013; Ramakrishnan & Yasin, 2010; Venkatesh, 2013; White , 2013; Yadav, 2013), social skills (e.g., Bacolod, Bernardo, & Strange, 2009; Borghans, Duckworth, Heckman, & Weel, 2008), and communication skills (Capretz & Ahmed, 2010; Di Meglio, 2008; Edwards, 2010; Mitchell, Skinner, & White , 2010; Pinsky, 2013). In addition, we found that terms used by sources in the employment literature to describe noncognitive skills often seemed to be industry-specific. For example, sources that focused on employment in the health services and nursing industries mentioned skills like empathy, whereas sources focused on the business or finance industries mentioned skills like project management (Ramakrishnan & Yasin, 2010; Shuayto, 2013; Stevenson & Starkweather, 2010).

Developing a taxonomy of noncognitive skills that spans higher education and employment literatures also enabled us to compare how each body of literature describes these skills, to consider whether skills that we view as conceptually coherent are represented differently in these two bodies of literature. By analyzing the rubric entries that were nested in each noncognitive skill in our taxonomy, we noticed some striking differences in how these skills were represented in the higher education and employment literatures, respectively. For example, collaborative skills were well covered in both the higher education and employment literatures, but when we took a close look at the rubric entries, we found that each body of literature described these skills differently. In the employment literature, the desired result is group productivity , whereas in the higher education literature the desired result is usually individual learning /development through the act of interacting with others. In other words, collaborative skills in the work place is often a desired result of, and integral to, the work itself, whereas in higher education , collaborative skills is treated as a means to the work of personal development, or even as something that must be endured along the way (hence the idea of “followership”).

Another example is motivation (nested under goal orientation in the taxonomy), defined in one workplace study by Barrick & Zimmerman (2009) as “desire for job” or “intent to stay”. This is quite different from other definitions of motivation in higher education articles , which tend to focus on conceptual definitions of motivation rooted in cognitive psychology, such as situated motivation toward a particular task or subject (Hodges & Kim, 2013; Lizzio & Wilson, 2013), intrinsic motivation or valuing of a task (Torenbeek, Jansen, & Suhre, 2013; Trainin & Swanson, 2005), as well as potentially detrimental sources of motivation such as failure avoidance (Boese, Stewart, Perry, & Hamm, 2013). These examples illustrate how many of the skills are uniquely defined by the context that they are in.

Discussion: Trends in the Scholarship

Our foray into this research was driven by a question about how noncognitive skills are represented in higher education and employment publications relative to college and career success , and the extent to which each sector was describing the same concepts. It was encouraging to find such a robust body of literature on a topic that has garnered much recent attention. However, review and subsequent analysis of the literature confirms the confusion and misalignment regarding the specific noncognitive terms being used to discuss college and career success , potentially explaining why field leaders are questioning students ’ readiness. The confusion appears most clearly around which exact skills are being described and implied when referencing noncognitive terms. The related misalignment seems most significant in the relatively uneven representation of skills within each sector across our three domain areas. In addition, we identified differences between these two bodies of literature in approaches to conceptualizing and defining skills, with implications for the evaluation of noncognitive skills . Although the field lacks a unifying framework, our analytic process revealed sufficient patterns that contributed to a taxonomy that allowed for the comparison of the two bodies of literature. These patterns suggest to us that alignment may be within reach given further articulation. In the following section, we describe our interpretation of these findings in consideration of an aligned system that would support both education and employment contexts.

Alignment of Noncognitive Skill Domains for Education and Employment

Our categorization of the wide array of noncognitive skills was influenced by identified commonalities across skills that suggested they could be further grouped into domains of related skills, thereby allowing us to distill 42 skills into an organizing framework. Using a unique “locus” or target point of the skills, we categorized the skills as follows: were the skills directed at a particular task, inwardly toward the self, or toward other people? This schema formed the basis for our three domains: Approach to Learning/Work , Intrapersonal Skills, and Social Skills.

The skills placed in the Approach to Learning/Work domain appear to build upon earlier research by Ausubel, Novak, and Hanesian (1978) and Marton (1976), who made a distinction between meaningful learning and rote learning . Marton’s (1976) work was particularly influential, as he introduced the theoretical concepts of “deep” and “surface” learning to describe the processes that students used when reading a text (Richardson, 2015). As Marton explained (1976), students with a deep approach to learning focused on what the text was about, using logical thinking to connect their prior knowledge to the material they were reading. Students who used a surface approach, by contrast, were more focused on memorizing the text. Students who used a deep approach “appear to experience an active role – learning is something they do” (Marton, 1976, p. 35). For surface learners, learning was more passive in nature -- “something that happens to them” (Marton, 1976, p. 35). Entwistle and Ramsden (1983) later introduced a “strategic” approach to studying and learning that referred to students ’ organization, study skills, and orientation toward achievement.

Previous studies not analyzed during our review also support the relationship between approach to learning and metacognitive development (Case & Gunstone, 2002). Flavell (1976) described metacognition as “one’s knowledge concerning one’s own cognitive processes and products or anything related to them,” and explained that it includes monitoring, regulating, and orchestrating information processing activities (p. 232). Likewise, earlier research by, Blåka and Filstad (2007), explored newcomers’ learning processes in two workplace communities. They found that in order to construct identities as workplace “insiders,” the newcomers had to learn appropriate language and cultural norms from more established colleagues. Eraut’s (2004) research on learning at work similarly reflects the range of skills in this domain, indicating that learning at work occurs as a result of not only undertaking activities and seeking out learning opportunities, but also successfully meeting challenges. Individuals’ confidence to take on challenges in the workplace depends upon how supported they feel; if workers are not provided with challenges, or they lack sufficient support to take on challenges, their confidence and motivation to learn will decline (Eraut, 2004). Our categorization of skills in the Approach to Work /Learning domain builds on these studies, further emphasizing a range of skills and behaviors necessary to approach work and learning tasks.

The skills categorized in the Intrapersonal Skill domain builds on past research such as Bar-On’s (2006) model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI), which is defined by Bar-On, Brown, Kirkcaldy, and Thomé (2000) as “the ability to be aware and understand oneself, one’s emotions and to express one’s feelings and ideas” (p. 1108). Studies using the ESI model suggest that intrapersonal skills including self-awareness and managing emotions strongly contribute to occupational performance (Bar-On, 2006). This categorization also builds on research showing a strong association between intrapersonal skills such as stress management abilities and academic performance (Parker, Summerfeldt, Hogan, & Majeski, 2004).

Previous research also suggests that the skills studies confirm that many of the individual skills grouped within the Intrapersonal domain are interrelated. For example, facets of conscientiousness include self-control (e.g., managing emotions) and responsibility – both of which have been shown to affect risk-taking (Charness & Jackson, 2009 ; Magar, Phillips, & Hosie, 2008) – as well as qualities related to personal values and ethical behavior and decision making such as traditionalism and virtue (Crossan, Mazutis, & Seijts, 2013; O’Fallon & Butterfield, 2005; Roberts, Chernyshenko, Stark, & Goldberg, 2005; Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004). Similarly, Le Pine, Colquitt, and Erez (2000) suggest that adaptability, one’s capacity to perform in a changing task context, may be a function of conscientiousness and openness. These other studies argue that conscientious individuals are more likely to persevere toward goals and make decisions in an orderly, deliberate way (Le Pine et al., 2000). However, this orderly, deliberate tendency on the part of conscientious workers can make it more difficult for them to make accurate decisions within changing task contexts (Le Pine et al., 2000) that require adaptability such as unpredictable, stressful, or crisis situations (Pulakos, Arad, Donovan, & Plamondon, 2000).

Previous research not reviewed in our study further provides important contextualization for the skills categorized in the Social Skills domain. Social intelligence, or more commonly termed social skills in our rubric, has been described as the “ability to effectively read, understand, and control social interactions,” is of particular importance in the contemporary workplace, with its heavy reliance on social interactions, and has been shown to affect work quality as well as task performance (Ferris, Witt, & Hochwarter, 2001, p. 1076). Grounded in earlier research by Marlowe (1986), social intelligence is multidimensional and includes concern for others as well as observable social behaviors . Research shows that social skills, the array of abilities and qualities encompassed by social intelligence, are predictive of contextual performance in a team setting (Morgeson, Reider, & Campion, 2005). These skills are also found in higher education contexts, positively influencing grade point average (GPA) over the first 2 years of college (Strahan, 2003). Importantly, these findings provide important explanation for the fact that the skills in this domain reflected the most alignment in high-frequency skills in our rubric across the two sectors.

Importantly, the three domains of noncognitive skills that emerged in our analysis—Approach to Learning/Work , Intrapersonal Skills, and Social Skills—are closely aligned with the three domains of “21st century competencies” for career readiness that were described by the National Research Council’s Committee on Defining Deeper Learning and twenty-first Century Skills (NRC, 2012). Based on its review of research from diverse academic disciplines and fields, the Committee delineated three domains of competence—cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal—and defined them this way:

The cognitive domain involves reasoning and memory; the intrapersonal domain involves the capacity to manage one’s behavior and emotions to achieve one’s goals (including learning goals); and the interpersonal domain involves expressing ideas, and interpreting and responding to messages from others. (NRC, 2012, p. 3)

The Committee wrote that these domains “represent distinct facets of human thinking and build on previous efforts to identify and organize dimensions of human behavior ” but also emphasized that these domains are “intertwined in human development” (NRC, 2012, pp. 21–22). The Committee characterized these three domains as representing “a preliminary classification” of twenty-first century competencies, not yet a definitive taxonomy (NRC, 2012, p. 21). The domains that emerged from our analysis provide validation of the NRC’s findings and illustrate their relevance for college success as well as career readiness.

Some members of that Committee expressed concern about separating skills into different “clusters,” arguing that “it is misleading to imply the clusters of skills are independent and mutually exclusive” or that “the clusters are discrete and unrelated” (NRC, 2011, p. 109). Members argued that these skills—and clusters, or domains, of skills—should instead be portrayed as interdependent and related. Like our predecessors, we recognize these challenges and add two additional considerations associated with grouping skills. First, there are multiple avenues for grouping; parent headings and categories may work in some settings and not in others. Our intention behind grouping was to create a taxonomy that can be used to examine mis/alignment across the literature. Second, we recognize that categorical boundaries have limited value; the fact that these skills are interconnected and developmentally cascading means that they can be grouped into more than one domain. Moreover, the categorical classification fails to illustrate the exact relationship, hierarchical or otherwise, between terms or domains.

We also conclude that differences in desired outcomes between higher education and employer contexts may explain the wide variety of terms and differing emphases on particular skills by sector. This may be related to the ways the contexts of each sector influence which outcomes are determined. In higher education , for example, outcomes are distinct and assessed objectively, whereas employers utilize less precise outcomes associated with non-cognitive skills such as “a good hire” or a “successful manager” and assess these outcomes subjectively. The lack of consensus regarding term conceptualization and definition and differing emphasis on particular skills by sector illustrate this concern. Higher education literature was relatively more focused on Approach to Learning/Work skills such as self-efficacy and attention control, while employment literature was comparatively more focused on Social Skills such as communication and collaboration. The finding may be partially attributed to the unique contexts of each setting, which affect not only the developmental trajectory of skills, but also which skills are fundamentally valued. For instance, while success in higher education is largely contingent on individual achievement, success in the workplace is often contingent on interactions with others. This may partially explain the emphasis on Social Skills valued by employers more than higher education officials.

An Unacknowledged Distinction Between Skills and Behaviors

A primary purpose of this study was to examine how the literature portrays the range of noncognitive skills believed to be necessary for success in higher education and the workplace. Our findings reveal variability in skills across the different domains in each context. Yet a careful analysis of the skills revealed a notable distinction between internal skills and capacities. For example, internal skills such as self-efficacy and self-direction are categorically different than behaviors that enact those skills, such as goal setting and taking initiative. We interpret this distinction by differentiating skills as core skills and enacted skills. Specifically, individuals rely on core skills to be able to enact a specific skill or behavior in any given context. For example, an enacted skill such as taking initiative is fostered by a set of core skills such as reflection, self-efficacy , internal locus of control, or openness. However, enacted skills may look different depending on their context—for example, in a college versus an employment setting—which may explain why the skills listed in our taxonomy sometimes manifested differently in the higher education and employment literatures; one body of literature might be describing the enacted skill, whereas the other literature base might be describing the core skill. What could unify these bodies of literature is the realization that, without attention to the core skills, individuals are unable to produce the behaviors that higher education officials and employers desire. While this distinction may appear minimal, differentiating the skills gives clear direction towards how to foster the development of skills as a strategy to promote desired behaviors in both higher education and employment contexts. Thus, whether the outcomes are course completion, GPA, degree attainment, job placement, or job promotion, we can distinguish between the behaviors that are specific to each sector and the internal, core skills that enable them.

As previously noted, many of the skills reviewed in this analysis appear to be context specific. To illustrate this point, let us use the same example above, taking initiative. In higher education , that behavior might take the form of taking a proactive approach to learning . However, in an employment setting, this behavior might manifest itself as producing results with minimal supervision or soliciting new clients. In both cases, the “core skills” required to take initiative might be the same (i.e., reflection, self efficacy); however, the “enacted skills” will appear quite differently dependent on context. The fact that skills seem to manifest uniquely in distinct contexts raises questions about the transferability of these skills. However, given that higher education and employment both comprise multiple contexts (e.g., residential setting, classroom, extracurricular, office, interaction with clients), it seems reasonable to assume that it would be difficult to develop “enacted skills” specific to multiple contexts.

Our distinction between core skills and enacted skills speaks to the work of Farrington et al. (2012), which teases apart different “categories” of noncognitive skills in order to better understand the nature of these skills and their relationships to academic achievement (p. 6). Among the categories they identify are academic behaviors , defined as “the visible, outward signs that a student is engaged and putting forth effort to learn,” and academic mindsets, defined as “the psycho-social attitudes or beliefs one has about oneself in relation to academic work” (Farrington et al., 2012, pp. 8–9). The authors argue that “much of the research conflates constructs that are conceptually very distinct” (Farrington et al., 2012, p. 74).

Farrington et al. (2012) argue that this lack of conceptual clarity around different categories of noncognitive skills is also evident in education practice, where “observable behaviors ” are often used “to infer and measure unobservable noncognitive factors such as motivation or effort,” which “conflates what could be very distinct factors (feeling motivated versus doing homework)” and “makes it difficult to pinpoint the leverage points whereby teachers, parents, or others might intervene to help improve student performance” (Farrington et al., 2012, p. 17). An in-depth study of one set of closely related noncognitive skills provides additional context for why contemporary researchers tend to conflate skills that are conceptually distinct. The study, by Dinsmore, Alexander, and Loughlin (2008), explores the “conceptual boundaries” between three related terms: metacognition , self-regulation, and self-regulated learning (p. 392). The authors argue that confusion about the nature of noncognitive skills can be traced back to the “distinct histories” of the various academic disciplines and fields that have engaged in research about these skills (Dinsmore et al., 2008, p. 404). They found that contemporary research often treats meta-cognition and self-regulation as “synonymous terms,” despite an important distinction in how these skills have historically been conceptualized and studied: research about meta-cognition has had “a clear cognitive orientation,” whereas research about self-regulation has been more “concerned with human action than the thinking that engendered it” (Dinsmore et al., 2008, pp. 404–405). In other words, the distinction that we see between core skills and enacted skills may speak to differences in the theoretical roots of noncognitive skills —some of which may have been originally conceptualized as mental processes and others as behaviors . However, as Dinsmore et al. (2008) note, terms like meta-cognition and self-regulation are often borrowed and used interchangeably by contemporary researchers in new fields who may not be sensitive their “varied theoretical roots” (p. 405), leading to confusion about what the terms mean and the loss of historical distinctions between mental processes and behaviors . Dinsmore et al. (2008) argue that the current confusion related to terms and definitions used to describe noncognitive skills is “not necessarily problematic”; instead, it reflects the fact that our conceptualizations of noncognitive skills are evolving as researchers from different disciplinary backgrounds contribute new theoretical and empirical understandings to a growing body of literature (p. 398).

These studies by Dinsmore et al. (2008) and Farrington et al. (2012) affirm our observation that there is an unacknowledged distinction between core skills and enacted behaviors in the scholarship, thus potentially leading to confusion among applied practices. Accordingly, we anticipate that a refined focus on “core skills,” along with a recognition that these skills will be enacted in different ways in different contexts, is a useful way forward. Re-conceptualizing alignment to focus on core skills highlighted in our taxonomy is a promising way to address questions of readiness and strategies for development.

Moving Towards an Alignment of Skills in Practice and Research

In light of these findings, we offer some thoughts on implications for practice and research in the fields of higher education and employment , respectively or collaboratively. Importantly, the lack of common language across sectors acts as an impediment both within and across higher education and employment . This incoherence may contribute to a narrative in which higher education and employers value different skills, when in fact the reality may be that preferred behaviors look different in respective contexts, but actually rely on the same core skills.

The taxonomy described in this paper was developed as a tool for research purposes; however, it also provides a starting point for greater coherence. Our study draws together the disconnected bodies of scholarship about noncognitive skills that support success in college and career in order to develop a unifying framework that can be used in both higher education and employment contexts. By helping organize and clarify the conversation about the role of noncognitive skills in college and career success , this framework may support more effective collaboration by the various constituencies interested in improving the educational and career transitions and outcomes of emerging adults (Snipes et al., 2012). In this case, the fact that our taxonomy depicts both core skills and enacted skills within domains can help people see the connections and recognize that instead of focusing on an enacted skill, they might survey the other skills in the domain and see if one of the core skills could actually be a more appropriate lever for change. Thus, we recommend that institutions review their current programming to assess whether they are appropriately targeting the core skills that promote behaviors necessary for college success and career readiness.

Finally, the fact that our taxonomy uses terminology from both the higher education and employment sectors also facilitates dialogue and partnership across the sectors. We recommend that employers partner with local institutions to foster conversation about skills where both fields can agree on their importance or meaning. For example, we imagine that employers from large industries might partner with state universities and community colleges , given the focus of many public institutions to build the state’s workforce . Forging these conversations offers the potential for employers to learn about which skills are being developed in higher education so that they can build their own skills-gap training programs. By the same token, colleges can learn more about what employers are looking for, thereby providing direction for colleges to leverage their existing services to help students graduate career -ready.

Directions for Future Research

This study was not designed to evaluate whether noncognitive skills matter for college and career success , nor was it intended to ascertain which skills are most conducive to college and career success . For this reason, and others, there is much room for future research on this topic. To begin, there is a need for increased empirical research, especially in the employment literature, that examines the relationship between these skills and success . Further research in this area will benefit related investments in alignment by ensuring that employers clearly understand and can assess the specific skills they believe to be critical in the workplace. Further, we contend that the field would benefit from greater clarity of terms and specifically, an articulation of how a set of internal, core skills can be employed to enact context-specific behaviors that are linked to desired outcomes. With clearer definition of terms, taking into account the differences in social context and distinguishing between skills/behaviors , there is an opportunity for much more common ground than is currently perceived. Moreover, explicit definitions for skills in empirical research are needed so that readers are not left to interpret the meaning behind a given skill.

The taxonomy we propose in this paper provides a common vocabulary for the diverse constituencies engaged in this discourse, as well as a framework for synthesizing empirical findings from many different disciplinary traditions. We recommend that future research use this, or a similar taxonomy, to examine different areas of alignment between higher education and employers.

The data from this study further suggest that there is a need for clearer links between research and practice. Research-oriented scales and scientific language bear little relevance to educators and professionals whose background is not in developmental psychology. Therefore, we suggest that scholars attend to the development of transferable and usable knowledge on the topic of noncognitive skills through the creation of applied or behavioral terms and definitions. In light of increasing institutional interest in developing these skills, future research must take into account how scales and other assessments can be used as a diagnostic tool for targeted interventions. Such tools provide important information to institutional agents, and students themselves, assuming they are accompanied by strategies for skill development and improvement.

In addition to shifts in the nature of future research, we believe there is a need to engage employers and higher education institutions to assess whether there is alignment of practice. Such research would assess which skills are being targeted and by whom, in each sector. Such a line of inquiry raises questions about whether there is shared responsibility in developing these skills. If so, then to what extent do employers screen for these skills in the hiring process rather than seeing their role as developing these skills in employees after they have been hired? A distinct, but related line of research might examine what types of strategies have been effective in developing these skills, as there is a gap in the literature regarding interventions that effectively develop noncognitive skills in higher education and employer settings.

Conclusion