Abstract

The present study investigates the impact of country-of-origin on Greek consumers’ corporate social responsibility (herein CSR) perceptions, behavioral intentions, and loyalty. Towards this end, two surveys were conducted, one for domestic and one for foreign companies. Results suggest that consumers expect from companies to respond to their legal, ethical, and discretionary responsibilities irrespective of their country-of-origin. However, Greek consumers demand from domestic companies to respond in a higher extent to their economic goals compared to their foreign counterparts. Moreover, they tend to favor national companies since they were found to be more willing to pay a higher price for domestic than for foreign products. Consumer loyalty was also affected by a company’s country-of-origin as consumers exhibited higher loyalty levels for products of domestic than of foreign corporations. Finally, several practical implications are discussed at the end of the paper.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Corporate social responsibility

- Consumers’ expectations

- Country-of-origin

- Willingness to pay a premium price

- Loyalty

- Domestic

- Foreign companies

- Greece

22.1 Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (herein CSR) has been the focus of research for many decades with researchers being interested in investigating whether companies implement “context-specific organizational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance” (Aguinis 2011, p. 855) and how these actions affect companies’ profitability and consumer perceptions. Part of this interest stems from the importance consumers assign to CSR initiatives undertaken by companies. In fact, consumers expect companies to act in a social responsible manner. Furthermore, empirical evidence suggests that consumers are influenced by CSR actions of companies. As Carroll and Shabana (2010) note, companies who invest in CSR can attract customers, build long term relationships as well as enhance their customers’ loyalty.

An interesting stream of CSR studies examine consumers’ perceptions of CSR activities by companies. For example, several researchers have looked at the effects of CSR on variables such as company and product evaluations (Brown and Dacin 1997; Mohr and Webb 2005), intentions (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001; Mohr and Webb 2005), trust (Maignan et al. 1999; Stanaland et al. 2011), perceived reputation (Stanaland et al. 2011), and customer loyalty (Maignan et al. 1999; Crespo and del Bosque 2005; Stanaland et al. 2011).

Although there are a considerable number of empirical studies which investigate the consequences of consumers’ perceptions of CSR actions, the impact of country-of-origin on CSR has not received much attention. To the best of our knowledge only the study of Han (2015) has examined the impact of country-of-origin on consumers’ expectations of CSR initiatives. Hence, the purpose of the present study is to examine whether consumers’ expectations of CSR activities differ between domestic and foreign companies. Specifically, the objectives of the present study are two-fold: First, to delineate the effects of country-of-origin on consumers’ perceptions of CSR activities, behavioral intentions, loyalty and second, to examine the relationships between consumers’ CSR perceptions, behavioral intentions, and loyalty.

22.2 Measurement of Corporate Social Responsibility

According to the work of Bowen (1953), which is considered to be the first publication on CSR issues, CSR is related to the actions of businessmen that are in line with the desires and values of the society. Often CSR is faulty related only with companies’ actions about environmental protection and philanthropy. These conceptualizations of CSR are narrow and do not consider the multi-dimensional nature of the construct. As Carroll (1979) stated, CSR activities should be oriented towards “the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations that society has of organizations at a given point of time” (p. 500). The economic aspect of CSR is related to a company’s orientation towards productivity and profitability. The legal responsibilities of companies refer to society’s expectations for companies to act according to the legal system and requirements. The ethical dimension suggests that companies should comply with the ethical norms and values of the society while the discretionary aspect of CSR includes the philanthropic contributions of companies and provision of voluntary services (Carroll 1999).

Several researchers have developed multi-dimensional instruments in order to measure consumers’ perceptions towards CSR activities of organizations. Maignan (2001) using the framework of Carroll (1979) developed a four-dimensional scale that captures consumers’ desire for economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary actions of companies. In particular, the economic factor consisted of items that measured perceptions about the necessity for companies to be oriented towards profit maximization, cost production control, long term success, and economic performance. The legal dimension captured consumers’ desire of companies to follow the principles of the regulatory system, to obey the law even if this will hurt economic performance, to carry out their contractual obligations, and to ensure that their employees act according to the law. The ethical dimension included items that assessed consumers’ demand from companies to act in an ethical way even if these actions will operate in the detriment of economic performance, to follow their well-defined code of ethics, and not to compromise their ethical values for the execution of business goals. Lastly, the discretionary element of Maignan’s scale evaluated consumers’ desire for companies to actively engage in activities that support social causes such as supporting philanthropic activities, participating in public affairs management, and solving social problems.

Another scale for the measurement of CSR was developed by Castaldo and Perrini (2004) and was comprised by three factors, namely environmental, consumer, and employee. Specifically, the environmental factor assessed perceptions about the extent to which a company is considered sensitive to environmental issues. The consumer dimension measures the degree to which consumers believe that a company is oriented towards consumer satisfaction and protection whereas the employee dimension evaluates the extent to which a company is perceived as a responsible employer that respects equality, avoids discrimination, and implements safety policies.

David et al. (2005) operationalized perceived CSR as a three-dimensional scale that consisted of three elements: moral, discretionary, and relational. Moral CSR actions refer to perceptions about whether a company treats fairly its employees, respects human rights, competes fairly with competitors, protects the environment, and communicates the truth in times of crisis and problems. The discretionary dimension is related to a company’s support of community and public health programs, contribution to social problems (i.e., hunger), and issues about children and family. Furthermore, the relational aspect of CSR included perceptions about the extent to which a company builds long term relationships with customer as well as engages in two-way communication.

Ten years later González-Rodríguez et al. (2015) validated a three-factor scale that was comprised of the following factors: economic, social, and environmental. The economic factor evaluated whether consumers’ purchasing decisions are influenced by practices such as job creation, profit maximization, low pricing of products/services, market leadership, and high investments in advertising. The social dimension incorporated practices like respect for human rights, provision of help for developing countries, training of employees, quality of life improvement, avoidance of discrimination, collaboration with schools, institutions, and universities, sponsorships of social and cultural activities, cooperation with NGOs, and charity organizations. Moreover, the environmental factor takes into account whether a company is interested in the quality and safety of products, tries to reduce the waste of resources and emissions of toxics, protects biodiversity and limited natural resources, promotes recycling, has an ethical code of conduct, and informs customers about the products’ composition.

Recently, Fatma et al. (2016) also measured consumers’ perceptions towards CSR using the same three dimensions as González-Rodríguez et al. (2015); however, the composition of the dimensions is different. Fatma’s et al. economic factor is similar to Maignan’s (2001) economic dimension and refers to the responsibilities of companies regarding economic survival, long term success, economic performance, control of cost production, and provision of information to shareholders about the economic situation of the company. The social factor includes practices that help companies solve social problems, improve the well-being of society, donate, favor disadvantaged, provide employees with equal opportunities, and support philanthropic causes. Finally, the environmental factor includes perceptions of consumers regarding the extent to which a company uses renewable energy in the production process, respects the environment, uses and produces environmental friendly materials and products, has environmental certification, and reports the environmental practices.

Based on the preceding analysis it can be argued that the instruments developed by researchers to measure consumers’ perceptions of CSR activities are comprised by similar factors. However, there is an inconsistency in the battery of items used to measure each factor/dimension. In the present study the scale developed by Maignan (2001) was utilized since it is the most widely accepted.

22.3 Conceptual Framework

More and more consumers prefer to support local companies and buy locally produced products and services while they view with suspicion and distrust multinational companies. As Park and Ghauri (2015) note local consumers view foreign companies as “exploiters” of domestic resources that try to pursue their profit maximization strategies. Under this climate of hostility CSR emerges as an important task for multinational companies who wish to reverse the skepticism of consumers in the host countries. In addition, CSR actions become imperative for multinational companies since “governments, consumer groups, and social organizations worldwide are demanding increased social accountability by multinationals” (Miles and Munilla 2004, p.6). In line with the above is the study of Han (2015) who revealed that Korean consumers hold greater expectations from European companies compared to domestic in regard to the economic, legal, and ethical responsibilities. Based on the aforementioned the following hypotheses are developed:

H1

Greek consumers will expect foreign companies to be committed to (a) economic, (b) legal, (c) ethical, and (d) discretionary responsibilities in CSR activities in a higher extent compared to their domestic counterparts.

Many countries under the devastating effects of global crisis try to encourage their citizens to “buy domestic” products (Chan et al. 2010) thus enhancing the levels of consumer ethnocentrism. According to Shankarmahesh (2006) ethnocentric consumers tend to prefer domestic products irrespective of their price or quality due to feeling of nationalism and patriotism. Hence, a consumers’ loyalty towards the nation might have a halo effect on his/her loyalty towards domestic products. In other words, consumer ethnocentrism is closely related to consumers’ loyalty for domestic products (Wong et al. 2008). Moreover, Knight (1999) found that ethnocentric consumers are more willing to pay a premium price for domestic products compared to foreign. Given that the present study is conducted in Greece where consumer ethnocentrism is high it is suggested that consumers will be more willing to pay a premium price and will exhibit higher levels of loyalty for domestic than for foreign products. Thus, the following hypotheses can be developed:

H2

Greek consumers will be more willing to pay a price premium for domestic than for foreign products.

H3

Greek consumers will be exhibit higher levels of loyalty for domestic than for foreign products.

Companies which engage in CSR activities are viewed more favorably by consumers. Moreover, for many consumers a company’s involvement in CSR tasks is an important criterion that affects their purchasing decisions. The significant impact of CSR on consumers purchasing intentions has been highlighted by a number of researchers (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001; Mohr and Webb 2005). In other words, a consumer will prefer to buy from a company that acts in a social responsible manner. Furthermore, CSR activities help companies build long term relationships with customers by enhancing their loyalty. Empirical evidence suggests that consumers’ loyalty is influenced by their perceptions about a company’s CSR commitment (Maignan et al. 1999; Stanaland et al. 2011; Crespo and del Bosque 2005). To put it another way, great expectations about a company’s CSR activities will lead to high purchasing intentions which in turn will improve consumers’ loyalty. Hence, the following hypotheses are introduced:

H4

Consumers’ expectations of (a) economic, (b) legal, (c) ethical, and (d) discretionary responsibilities will significantly influence their willingness to pay a price premium .

H5

Consumers’ expectations of (a) economic, (b) legal, (c) ethical, and (d) discretionary responsibilities will significantly influence their loyalty.

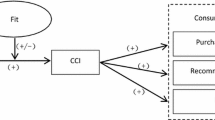

Figure 22.1 illustrates the conceptual model that will be tested by the present study.

22.4 Methodology

In order to achieve the study’s objectives two surveys were conducted to two groups of consumers. Two versions of the same paper-and-pencil questionnaire were designed to collect data (one for domestic and one for foreign companies). The questionnaire was organized into three sections. The first section measured consumers’ perceptions of CSR activities using the 16-item scale developed by Maignan (2001). Specifically, on a five-point scale consumers rated the extent to which they believed that (domestic/foreign) companies must engage in the 16 CSR activities. The second section included questions regarding respondents’ loyalty, and willingness to pay a price premium. Willingness to pay a price premium and loyalty were measured using the scales developed by Castaldo and Perrini (2004). It should be noted that three items were used to assess loyalty and three to evaluate consumers’ willingness to pay a higher price. Responses to the items were made on a five-point Likert scale ranging from (1) totally disagree to (5) totally agree. Finally, the third questions consisted of the demographic variables such as gender, age, marital status, education, and income.

The questionnaire for domestic companies was distributed to 101 respondents while for foreign companies was completed by 100 subjects. We used non-probability sampling techniques and specifically, convenience sampling since the two surveys were conducted at public places such as streets, cafes, and shopping malls in a Northwestern city of Greece. The surveys took place during September 2015. Special care was taken so as the two groups of respondents (one for foreign and one for domestic companies) are similar in terms of demographic characteristics. Table 22.1 shows the demographic characteristics of each sample.

Based on Table 22.1, we had an equal representation of the two genders in both samples. Moreover, the majority of respondents in both samples were single, aged between 18 and 35 years old, completed secondary education or were Bachelor’s graduates, and earned up to 2000€ per month. Chi-square tests were conducted to test whether the two samples differed in their demographic characteristics (see Table 22.1). Results indicate that the two samples (respondents who answered the questionnaire for domestic companies versus respondents who answered the questionnaire for foreign countries) did not differ at 0.05 level of significant in terms of gender (χ 2 = 0.125, sig = 0.724), age (χ 2 = 3.089, sig = 0.543), marital status (χ 2 = 3.366, sig = 0.339), and monthly income (χ 2 = 3.071, sig = 0.689). Hence, the two samples are homogeneous and results regarding their CSR perceptions are comparable.

Table 22.2 shows the mean values and the standard deviations for the items that comprise the four CSR dimensions (economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary) across the two samples.

Based on the mean values it can be argued that consumers require from Greek companies to respond mainly to their economic obligations while from foreign companies desire to set as a priority their legal responsibilities.

Table 22.3 shows the mean values and the standard deviations for the items that measure consumers’ loyalty and willingness to pay a premium price across the two samples.

Based on Table 22.3, Greek consumers exhibited higher levels of loyalty for domestic companies compared to foreign, while they seem more willing to pay a higher price for Greek products rather for products of multinational companies.

Next, in order to test H1 we developed four summative scales, one for each of the CSR dimensions (i.e., economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary). The internal consistency of the four summative scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The values of Cronbach’s alpha for the CSR scales are presented in Table 22.2. Based on the results, the internal consistency of the scales was deemed as satisfactory as alpha values exceeded the 0.60 criterion. Then independent samples t-tests were conducted to test whether consumers’ expectations for economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary responsibilities differ between domestic and foreign companies (see Table 22.4).

Based on the findings, significant differences (p < 0.05) were found in the mean scores of the economic dimension between domestic and foreign companies (t = 4.432, p = 0.000). Specifically, consumers’ hold greater expectations from Greek companies in regard to their economic responsibilities (M = 16.23) compared to their expectations from foreign corporations (M = 14.80). Interestingly, no significant differences were observed (p > 0.05) in the mean scores of consumers’ expectations between domestic and foreign companies for the legal (t = −0.286, p = 0.775), ethical (t = 1.195, p = 0.234), and discretionary (t = 1.603, p = 0.111) responsibilities. Thus, H1a could not be rejected while H1b, H1c, and H1d were rejected.

In regard to H2 and H3, again two summative scales were constructed for willingness to pay a premium price and loyalty after assessing their internal reliability. The Cronbach’s alpha values for the two scales were 0.83 and 0.71, respectively, indicating a good internal reliability. Next, two independents samples t-tests were conducted to examine whether consumers’ willingness to pay a premium price and loyalty differ between domestic and foreign products (see Table 22.5).

As Table 22.5 shows, significant differences (p < 0.05) exist in the mean scores of consumers’ willingness to pay a premium price between domestic and foreign products (t = 7.110, p = 0.000). Looking at the mean values it can be concluded that Greek consumers are more willing to pay a higher price for Greek (M = 8.75) as opposed to foreign products (M = 6.20). Hence, H2 is accepted. Similarly, consumers’ loyalty differs significantly (p < 0.05) between domestic and foreign products (t = 5.337, p = 0.000). As a result, Greek consumers are more loyal to domestic products (M = 8.74) compared to their foreign counterparts (M = 6.99). Thus, H3 is accepted.

To test H4 and H5, that is the effect of the four CSR dimensions on willingness to pay a premium price and loyalty, a structural equation analysis was conducted. Structural equation modeling analyzes and examines simultaneously more than one relationship among multiple dependent and independent latent and/or observable variables (Jöreskog et al. 1999). The overall chi-square statistic of the measurement model was significant [χ 2(195) = 304.58, p = 0.000], which is accepted for large samples. The goodness-of-fit indices of the model exceeded the 0.90 criterion [CFI (Comparative-fit-Index) = 0.923, IFI (Incremental-Fit Index) = 0.924]. Moreover, the RMSEA value was smaller than the accepted by the literature threshold of 0.07 (RMSEA = 0.053). Based on the above results, it can be suggested that the hypothesized model showed a reasonably good fit to the data.

Support for the hypotheses was examined based on the significance of the standardized estimates of the path coefficients which are shown in Table 22.6.

The hypotheses testing concluded that consumers’ willingness to pay a price premium was not affected in a significant manner by any of the four CSR dimensions. Hence, H4 was rejected. In regard to H5, results indicate that the economic dimension of CSR is a significant (p < 0.05) predictor of consumers’ loyalty (b = 0.216). Moreover, the discretionary dimension had also a significant influence (p < 0.05) on loyalty (b = 0.370). However, the legal and ethical dimensions did not affect loyalty. Thus, H5a and H5d were accepted and H5b and H5c were rejected. Hence, one can conclude that consumers’ loyalty will increase as long as their expectations of economic and philanthropic responsibilities of companies will increase as well. The relationships between the economic and philanthropic dimension with loyalty were weak in strength.

22.5 Conclusions

Contemporary consumers expect companies to behave in a socially responsible manner. Moreover, they are turning their backs on multinational companies while simultaneously are interested in supporting their domestic companies. Under the threat of economic crisis, Greek consumers are becoming more and more ethnocentric and their buying decisions are influenced by a company’s country-of-origin. In this high ethnocentric environment, what Greek consumers expect from domestic as well as from foreign companies regarding CSR? Are these expectations different based on the company’s country-of-origin? How consumer loyalty and buying intentions are affected by the country-of-origin? These are some of the research questions addressed by the present study. Specifically, the aim of the present study was to test whether consumers’ expectations of CSR, willingness to pay a higher price, and loyalty differ between domestic and foreign companies. Moreover, the present study examined the effect of consumers’ CSR expectations on (a) willingness to pay a premium price and (b) loyalty.

Results indicate that consumers’ expectations regarding the legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities of companies are not differentiated based on the companies’ country-of-origin. Thus, they require from companies to respond to their legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities irrespective of their country-of-origin. In contrast, Greek consumers expect from domestic companies to be more oriented towards the improvement of their economic performance. This finding could be attributed to the fact that consumers in the face of economic crisis desire their national companies to have robust economic performance and to increase their profits in order to revitalize the Greek market and economy.

In addition, evidence of high consumer ethnocentrism and national loyalty were also found in Greek consumers who are willing to support domestic companies by paying higher prices and re-purchasing their products. On the contrary, Greek consumers are becoming less supportive of foreign companies. Another finding of the present study is the significant impact of consumers’ CSR expectations on loyalty. It seems that consumers will favor companies which respond to their economic and philanthropic obligations. Hence, Greek consumers’ loyalty is related to a company’s profitability and philanthropic profile.

The present study has several managerial implications. As results suggest, companies irrespective of their country-of-origin should implement CSR initiatives that focus on their economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary obligations towards the society. Companies wishing to enhance their customers’ loyalty need to improve their economic performance and pursue philanthropic initiatives. This becomes imperative especially for foreign companies which operate in Greece and want to counterbalance Greek consumers’ ethnocentrism and preference for domestic products. As far as Greek companies are concerned, it is herein suggested that they start responding to consumers expectations of profitability and performance so as to rebuild consumers’ confidence. A robust economic performance in conjunction with a philanthropic orientation is the main key to create loyal customers.

The main limitation of the present study stems from the convenience nature of the two samples. Moreover, the small samples used in the study add bias to the representativeness of the results. Additional research could be directed towards the investigation of other antecedents of consumers’ CSR perceptions.

References

Aguinis H (2011) Organizational responsibility: Doing good and doing well. In: Zedeck S (ed) APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, 3rd edn. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp 855–879

Bowen HR (1953) Social responsibilities of the businessman. Harper & Row, New York

Brown TJ, Dacin PA (1997) The company and the product: corporate associations and consumer product responses. J Market 61(1):68–84

Carroll AB (1979) A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad Manag Rev 4(4):497–505

Carroll AB (1999) Corporate social responsibility evolution of a definitional construct. Bus Soc 38(3):268–295

Carroll AB, Shabana KM (2010) The business case for corporate social responsibility: a review of concepts, research and practice. Int J Manag Rev 12(1):85–105

Castaldo S, Perrini F (2004) Corporate social responsibility, trust management, and value creation. In: 20th EGOS Colloquium, the organization as a set of dynamic relationships. Ljubljana University, Ljubljana, pp 1–30

Chan TS, Chan KK, Leung LC (2010) How consumer ethnocentrism and animosity impair the economic recovery of emerging markets. J Glob Market 23(3):208–225

Crespo AH, del Bosque IR (2005) Influence of corporate social responsibility on loyalty and valuation of services. J Bus Ethics 61(4):369–385

David P, Kline S, Dai Y (2005) Corporate social responsibility practices, corporate identity, and purchase intention: a dual-process model. J Public Rel Res 17(3):291–313

Fatma M, Rahman Z, Khan I (2016) Measuring consumer perception of CSR in tourism industry: scale development and validation. J Hospitality Tour Manag 27:39–48

González-Rodríguez MR, Díaz-Fernández MC, Simonetti B (2015) The social, economic and environmental dimensions of corporate social responsibility: the role played by consumers and potential entrepreneurs. Int Bus Rev 24(5):836–848

Han CM (2015) Consumer expectations of corporate social responsibility of foreign multinationals in Korea. Emerg Markets Finance Trade 51(2):293–305

Jöreskog K, Sörbom D, du Toit S, du Toit M (1999) LISREL 8: new statistical features. Scientific Software International, Chicago

Knight GA (1999) Consumer preferences for foreign and domestic products. J Consum Market 16(2):151–162

Maignan I (2001) Consumers’ perceptions of corporate social responsibilities: a cross-cultural comparison. J Bus Ethics 30(1):57–72

Maignan I, Ferrell OC, Hult GTM (1999) Corporate citizenship: cultural antecedents and business benefits. J Acad Market Sci 27(4):455–469

Miles MP, Munilla LS (2004) The potential impact of social accountability certification on marketing: a short note. J Bus Ethics 50(1):1–11

Mohr LA, Webb DJ (2005) The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. J Consum Aff 39(1):121–147

Park BI, Ghauri PN (2015) Determinants influencing CSR practices in small and medium sized MNE subsidiaries: a stakeholder perspective. J World Bus 50(1):192–204

Sen S, Bhattacharya CB (2001) Does doing good always lead to doing better? consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J Market Res 38(2):225–243

Shankarmahesh MN (2006) Consumer ethnocentrism: an integrative review of its antecedents and consequences. Int Market Rev 23(2):146–172

Stanaland AJ, Lwin MO, Murphy PE (2011) Consumer perceptions of the antecedents and consequences of corporate social responsibility. J Bus Ethics 102(1):47–55

Wong CY, Polonsky MJ, Garma R (2008) The impact of consumer ethnocentrism and country of origin sub-components for high involvement products on young Chinese consumers’ product assessments. Asia Pac J Market Logist 20(4):455–478

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Pouliopoulos, L., Pouliopoulos, T., Triantafillidou, A. (2017). The Effects of Country-of-Origin on Consumers’ CSR Perceptions, Behavioral Intentions, and Loyalty. In: Tsounis, N., Vlachvei, A. (eds) Advances in Applied Economic Research. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48454-9_22

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48454-9_22

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-48453-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-48454-9

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)