Abstract

The U.S. is a regulatory state where major industries and firms throughout the economy are subject to extensive command and control regulation. Put another way, America is an entangled economy where concepts of seperate private from public enterprises and occasional intervention to affect market outcomes no longer apply. There is regulation at every margin. Drawing on the Bootlegger/Baptist theory, this chapter seeks to explain how special interest group demand for command-and-control regulation, as opposed to other forms of regulation, such as the use of performance standards and economic incentives, has accommodated and reinforced the rise of the regulatory state. The chapter traces the evolution of regulation theory to the present and then provides evidence on the rise of regulation and its effects.

The authors are Associate Director of Research at the Center for Politics & Governance and Lecturer at the Economics Department, University of Texas at Austin and Dean Emeritus, College of Business and Behavioral Science, Clemson University and Distinguished Adjunct Professor of Economics, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, respectively.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

Since the early 1970s, the U.S. economy has experienced significant and rarely interrupted growth in federal regulation. We see this, for example, in Fig. 1, which reports the annual count of pages of new and modified rules published in the U.S. government’s Federal Register, across the years 1940 through 2014. The Federal Register is the official daily chronicle for all newly proposed and final rules produced by the federal government. As readily observed, the 1970s set a high bar for later growth.

Part of this sudden expansion of rules is explained by the creation of new regulatory agencies. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was established in 1970 along with major environmental statutes that required development of rules affecting air, water, and land pollution. The U.S. Consumer Products Safety Commission and Occupational Safety and Health Administration were also established in the early 1970s as new federal statutes were passed that supplanted state and local regulatory dominance and increased the pace of activity for older regulatory agencies.

Growth in the economy itself may have also stimulated growth in regulation. It is possible that a larger—and more complex—economy somehow requires additional federal rules. To illustrate this possibility, Fig. 2 reports the count of Federal Register pages divided by real GDP. In fact the 1970s regulatory surge is even more pronounced when adjusted for GDP.

Along with technical change that spurred economic growth and, perhaps, the demand for federal rules, the 1970s marked the final formation of a national market for consumer goods accommodated by network television (Yandle 2010). Participants in national markets called for federal rules to replace the multiplicity of state and local regulations that previously regulated locally produced goods and services. Thus, there may have been other exogenous stimuli that led to high growth in central government regulation.

Volumes have been written analyzing the rise of the U.S. administrative state, and countless journal articles, along with journals to publish them, have emerged since the 1970s partly in an effort to explain and predict the surge of U.S. regulatory activity. It is not our intention to review or add to this literature. Instead, we assume a simpler task. We seek to explain why, within the regulatory surge, technology-based command-and-control (or CAC) regulations (i.e., regulations that are implemented using CAC instruments) became the instrument of choice as the U.S. economy became entangled with federal rules (Smith et al. 2011). We wish to explain what made CAC instruments so attractive, relative to other regulatory instruments, e.g., taxation, the setting of performance standards, or use of property rights, that might have been chosen.

Our explanation applies Public Choice concepts to highlight the behavior of economic and political agents when operating in the political arena. As the title to our paper implies, we refer to the political arena as the “Garden of Good and Evil.” We see the political arena as a commons where interacting participants, when regulating, can take actions that, at the margin, may improve the wealth of the nation, a good outcome, or as a place where political agents act in ways that reduce overall well-being, which we refer to as an evil outcome. From within the Public Choice toolkit, we select and enrich Yandle’s (1983) Bootlegger/Baptist theory of regulation and use it as a foundation for explaining why CAC methods became the instrument of choice.

In applying Yandle’s theory, we will show how CAC regulations can embody elements of good (welfare enhancing) and evil (welfare reducing) in the same regulation and by doing so become extraordinarily attractive to participants in the Garden of Good and Evil. We note that when good and evil are packaged in the same regulation, durable coalitions form to reduce the political cost of forming regulation. We also note that it is impossible, a priori, to draw firm conclusions regarding a bundled regulation’s overall welfare effects. Put another way, we offer a positive analysis of the political economy, one that aims to explain the way the world works, as opposed to a normative argument that claims to evaluate desirability of outcomes.

This chapter is organized as follows: In Sect. 2, we develop additional background on the rise of U.S. regulation and review theories of regulation that have been offered by historians, political scientists, and economists in an effort to explain regulatory behavior. We also discuss the choices made when politicians are selecting which regulatory instrument to apply as they construct a regulatory apparatus; we go on to describe some of the forces that favor one instrument over another. Section 2 also introduces the Bootlegger/Baptist theory.

Section 3 Footnote 1 enriches the Bootlegger/Baptist theory and focuses on the politician’s challenge: How to satisfy the regulatory demands of diverse interest groups who are essential to his political success? To enrich the story, we draw on the work of Bueno de Mesquita and Smith (2012), which provides a useful framework for a finer grain analysis of politician and interest group interaction. The political solution to the politician’s challenge calls for development of a hybrid regulatory package, one that satisfies the regulatory demands of both public and private interests (Shamoun 2013). Drawing on a metric developed at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, Sect. 3 also provides evidence on the frequency of CAC regulation. The frequency and related effects, which we report, support our contention that the U.S. has become an entangled economy (Wagner 2009) because of the fertile soil the Bootleggers and Baptists have found in the Garden of Good and Evil. We conclude the paper with brief final thoughts.

2 Choosing How to Regulate

The explosion of U.S. federal regulation that began in the 1970s revealed a fundamental challenge to politicians who were constructing the legislative blueprints that instructed regulatory agencies as to how to build the detailed regulation that followed. The challenge had to do with which instrument to select for achieving the regulatory goal. Would the pending regulatory focus be better implemented by imposing price controls or higher taxes and fees, assigning property rights, regulating entry and exit, and setting performance standards; or would the rules describe changes in how, when, where, and by whom goods and services may be produced?

Regulations can be dichotomized into two broad categories: social or economic. Social regulations generally address issues relating to health, safety, security, and the environment. They are normally focused on a narrow issue, e.g., carbon emission, but their jurisdiction can extend to multiple industries, such as energy and transportation (e.g., coal plants, automobile manufactures, etc.). Economic regulations, on the other hand, deal with entry, quality of service, fares, prices, and rates of return in specific industries, such as transportation, communications, water, electricity, and natural gas (Brito and Dudley 2012). Both of these categories of regulations can be fulfilled using several instruments, such as, economic incentives, performance standards, property rights, or by implementing CAC approaches. While market-based and performance-based instruments dictate the outcome of the regulation, CAC instruments dictate the means by which the regulatory outcome is to be achieved. Historically, economic regulation has been attained by the former, and social regulation the latter.

When selecting regulatory instruments, the differences within the two categories are by no means trivial. For example, scholars were in broad agreement that setting performance standards, for example, to reduce carbon emissions by 30 % over some baseline, using any approach that might be chosen by regulated parties, was the low-cost regulatory approach. Performance standards did not require centralized authorities to ferret out dispersed knowledge and then decide once and for all, for example, how refrigerators should be built or electricity-generating plants operated. The use of performance standards provided competitive discovery incentives, made it possible to introduce new technologies when they were developed, and gave bottom-line incentives to minimize cost. Performance standards forced regulators to focus on outcomes—were the regulations really performing?—instead of on means—were the plants and machines being appropriately operated according to some standards?

Employing economic incentives was another theoretically attractive regulatory choice. For example, defining once and for all a limited number of emission allowances and allowing trade in them to constrain carbon emissions could also induce discovery of lower cost control techniques. Alternately, the use of emission fees and taxes would do the same thing. Setting a price on any unwanted activity would encourage economic agents to economize and reduce their harmful behavior. Again, regulators would not have to get into the engineering business; they could focus on outcomes, not means.

Finally, regulators could go the high-cost route of implementing CAC instruments, limiting discovery incentives. They could attempt to become experts in designing electricity generators, steel mills, food processing plants, automobiles, air conditioners, and all other major pollution sources and develop engineering standards that specify how emissions would be reduced. This, in fact, became the dominant U.S. regulatory instrument. We seek to explain why.

2.1 The Choice of Regulatory Instruments: A Political Choice

Whether an activity is regulated by means of CAC instruments or by means of economic- or performance-based instruments is a political choice. As mentioned, protection of air and water quality can be achieved by specifying the kinds of machinery to be operated by polluting firms—a CAC approach—or protected by imposing discharge fees or taxes on all polluters and other users of the scarce environmental assets, which would be an economic-based approach. Furthermore, air and water quality can be protected by limiting the entry of firms and organizations whose activities will consume environmental quality. In other words, environmental regulation could be designed in ways that satisfy the definition of economic-based instruments. In addition, the environment can be protected by establishing property rights that empower right holders to bring a legal action against polluters who impose cost on them without their permission. Similar approaches—fees, taxes, fines, and rights—could be devised to manage safety, health, and consumer protection. When writing regulation-spawning laws, politicians make choices.

Despite the feasibility and efficacy of economic- and performance-based approaches in implementing social regulations, politicians have begun to consistently rely on the use of CAC instruments to achieve their goal. Therefore, the increase of social regulations has been accompanied by the increase of CAC instruments. A record reflecting the distribution of regulations by category is shown in Fig. 3, which reports the budgeted expenditures for U.S. regulatory agencies across the years 1960–2015. The chart shows data for three regulatory categories: economic, social, and transportation safety administration, which is the expenditure for air travel security that followed 9/11. Obviously, when it comes to the use of tax dollars, politicians strongly favor social regulations, which gives us an idea of how often CAC instruments are invoked when crafting regulations.

Public Choice logic suggests why this would be the case. CAC instruments enable politicians to more accurately predict and target which firms, technologies, and industries will be most affected, and which constituencies will bear the greatest cost and which will receive the larger benefit. In addition to targeting, CAC approaches can achieve regulatory outcomes while at the same time hiding the incremental cost associated with the regulation. Consumers of air quality will not receive a monthly bill, nor will statements of charges be sent systematically to industrial firms that discharge waste into rivers, produce faulty consumer products, or operate unsafe workplaces. And of course, it is possible to have uniform rules and differential enforcement, which may make this approach all the more attractive to politicians.

2.2 What Theory Explains Regulator Behavior?

These last few statements raise questions regarding what motivates regulators. Can their actions best be explained by appealing to Public Choice logic, which suggests that politicians, like other normal people, are motivated by hope of personal gain, whether it be continued employment, higher future income, or social esteem? Or, alternatively, are political regulators driven primarily by an altruistic desire to serve the broad public interest to make the world a better place? There are, after all, competing theories to consider. Over the decades, political scientists, historians, and economists have struggled to develop a positive theory of regulation. Each theory has its strengths and its weaknesses (Brito and Dudley 2012).

The oldest of these explanations is called the Public Interest Theory and is associated erroneously with the name of Arthur Cecil Pigou (1920), a noteworthy English economist who, among other topics, focused on addressing the problem of social cost. Pigou described countless situations where, in his opinion, private action imposed largely uncompensated costs on the public at large. These included drivers of cars that wore out city streets, women who worked instead of caring for their children, and the more typical cases of factories that belched smoke on clothes drying at a nearby laundry. All of these could theoretically be addressed by an all-knowing political body. Pigou (1920) later indicated that no political body would behave in ways to serve the public interest in such matters, but would instead be swayed by special interest influence.

Under the Public Interest theory, government regulators are seen as working diligently to serve the broad public interest. Not motivated by the prospects of personal gain, these regulators work to correct market failures that lead to monopolized markets, environmental degradation, and shoddy consumer products, and also to protect the wealth, health, and safety of low-paid workers. Whether couched in terms of externalities, underprovision of public goods, or information asymmetries, the work of the public-spirited regulator is seen as being on the side of angels, while recognizing that regulators are still human.

While close observers of political action will likely agree with Pigou that special interest influence does seem to prevail when government spending programs are debated or tax policy considered, there is still a deeply committed group, especially among environmentalists, who act as though they believe regulators will more generally serve the public interest, which they claim is also their interest. Generally speaking, supporters of environmental CAC instruments do not see the process generating those rules as being just another part of transaction politics where politicians deliver regulations, just as they might shuffle to their supporters increases in particular packages of defense spending, all in exchange for political support.

Dissatisfaction with the overall usefulness of Public Interest theory for explaining political behavior, led to the development of a second theory of regulation, the Capture Theory, which was elaborated by Bernstein (1977) and Kolko (1963). Capture Theory can be thought of as beginning with a committed Public Interest regulator who truly seeks to provide a cost-minimizing or welfare-maximizing regulatory bundle. But in the course of seeking information about the problem to be addressed, becomes acquainted with, let us say, industry officials who work diligently to provide useful data and analysis to the politician. Unwittingly, perhaps, the politician becomes captured or unduly influenced by industry. According to the theory, this is how the public interest is compromised.

If one must choose either Capture Theory or Public Interest Theory for explaining the behavior of politicians engaged in a long series of regulatory transactions, one might be tempted to name Capture Theory the superior model. After all, the theory recognizes the economic value of regulations that can be provided politically, while simultaneously accepting the reality of transactional politics. Yet while it may be more useful, it suffers from a major shortcoming. There are often competing interest groups that wish to influence political outcomes.

For example, when fuel producers, engine manufacturers, and transport companies are involved with rules intended to reduce nitrogen oxide emissions from heavy trucks, it is not clear what the regulatory outcome would be. Will the nitrogen oxide rule reflect primarily the wants and interests of the fuel producers more than those of the transport companies and the engine manufactures? Along with these, in the same example, there can be environmentalists, health advocates, and state and local governments who seek different regulatory outcomes. Capture Theory offers no logic for predicting which among many interest groups will capture the politician.

This inherent weakness was addressed when Nobel Laureate Stigler (1971) developed the economic or Special Interest Theory of regulation. Professor Stigler suggested that to predict which interest groups will prevail in a regulatory contest, one should imagine an auction where the politician offers her vote to the highest bidder. The interest group that bids the most will be the one with the most to gain or the most to lose if unable to prevail. Of course, having a low-cost advantage in organizing a winning bid within an interest group involves developing the bid, dealing with dissenters, and in doing all this, minimizing transaction costs. Stigler’s model of enriched capture theory offers a large dose of insight for those who wish to understand regulatory outcomes.

There is yet one more important dimension to consider when elaborating theories of regulation. Those who demand regulation or seek to avoid regulation are willing to support politicians who accommodate them. But while the special interests who seek regulation need no explanation when the promised rules are delivered to them, politicians must justify their actions to their broad support base. They must be prepared to explain their actions in terms that go beyond simply trying to assist an industrial group in gaining monopoly power. Doing so is simplified when the politician can make a moral appeal and state that he was simply trying to do the right thing, that he was attempting to serve the public interest. Combining public interest justification—“We must take care of the environment for the sake of our children!”—with special interest demand for regulation—“Give us a rule that sets higher standards for new entrants than established ones”—introduces Yandle’s (1983) Bootlegger/Baptist theory of regulation.

2.3 The Road to the Garden Is Paved with Good Intentions

The Bootlegger/Baptist theory of regulation draws its name from episodes in rural America that involved the regulation of the sale of alcoholic beverages. Historically in rural areas there were two groups that supported state laws that shut down liquor stores on Sundays. These were Baptists, religious groups who opposed the sale of demon rum at any time, but especially on Sunday, and Bootleggers who bought their booze on Saturday and resold it on Sunday, at a profit, when legal competition was eliminated. One group, the Baptists, gave the politicians moral justification for shutting down the legitimate sellers. The Baptists also monitored the situation to make certain the laws were enforced. The Bootleggers, on the other hand, welcomed Baptist enforcement assistance and sometimes provided financial contributions to the political campaigns of local law enforcement officers as well as to elected politicians who made certain the desired laws were renewed regularly.

When Sunday closing laws were up for renewal, the Bootleggers never marched in front of state capitals looking for ways to raise rivals’ costs. They did not have to. The Baptists did that for them.

The Bootlegger/Baptist theory requires at least two kinds of interest groups. One provides moral justification for a regulatory action. The other group, which is in it for the money, helps to grease the political rails. It is, of course, possible for there to be multiple Bootlegger and Baptist groups, and we will illustrate this later. Historically, in the classic case, the two groups sought the same outcome and, while never meeting to conspire, were willing to struggle mightily to succeed. At the height of its success, this powerful pairing entirely shuts down the legal sale of alcoholic beverages in counties, states, and—during Prohibition (1920–1933)—the nation as a whole (Boudreaux and Pritchard 1994). We should quickly note, however, that Bootleggers never supported laws that limited consumption, although their Baptist brethren might. Instead, the two dissimilar groups found middle ground with closing laws that limited the extent of the market. The point is a critically important one that we will emphasize later. The Bootlegger/Baptist theory may not be useful in explaining the fact that regulation limiting the market for alcoholic beverages occurred when it did, but it can be powerful in explaining the fine print of regulations.

The theory helps to explain why, for example, federal laws designed to improve air and water quality impose CAC regulations that are stricter and more costly for new pollution sources than for older ones (Yandle 2013), why costly scrubbers were required for electricity-generating plants no matter which coal—clean or dirty—they burned (Ackerman and Hassler), and why major tobacco companies, state governments, and health advocates jointly oppose the unregulated sale of e-cigarettes (Adler et al. 2013). In a similar way, environmental groups and producers of natural gas and solar panels support regulations that control greenhouse gas emissions, the former due to concerns about global warming, the latter in pursuit of a competitive advantage (Buck and Yandle 2002).

The present campaign to regulate the largest transportation company, Uber, is a further illustration of the working of the Bootleggers, the taxicab drivers, and the Baptists, those concerned with passengers’ safety and welfare, which are allegedly compromised in the absence of government regulation. Bootlegger/Baptists coalitions understandably can lead to situations where those in it for profit subsidize those who take the moral high ground and are thus better positioned to become outspoken regulatory advocates. For example, U.S. producers of natural gas made major contributions to the Sierra Club when the environmental organization was lobbying the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to impose high-cost regulations on coal-fired electricity generating plants (Walsh 2012). In a sense, the Bootleggers became Baptists—or were at least baptized.

We point out again that successful Bootlegger/Baptist support of a particular regulation does not mean that the outcome is bad for the economy or for society as a whole, somehow measured. Transaction politics is part and parcel to the operation of the U.S. political economy. Rent-seeking drives interest groups to organize and then compete in the political commons with other rent-seekers. But again, we note that just as it is possible for an outcome to be good, it is also possible for it to be evil. When Bootleggers and Baptists enter the Garden of Good and Evil, anything can happen.

3 The Dynamics in the Garden of Good and Evil

In our model, Baptists want a targeted activity to stop. They believe consumption of alcoholic beverages, for example, is harmful to both the actor and society. Bootleggers do not want the activity to be stopped; instead they want to corner the market. A Bootlegger would like the activity to be restricted—so long as they are positioned to reap windfall profits from its restriction. The Baptists use persuasion as a means to end the activity. Their arguments resonate because, while they may sometimes be misguided, they are delivered in earnest. The Baptist realizes, though, that for activities for which the demand is very inelastic, there will always be those for whom persuasion alone is never persuasion enough. They will resort to the power of the state only as a last resort. The Bootlegger resorts to the state on principle. Bootleggers are not constrained in their rhetoric to truthful statements, whether delivered in earnest or not. Nor do they feel constrained to the use of rhetoric alone; they are merely interested in what works.

On its face this arrangement would seem unlikely to consummate. If Baptists recognize that the motivation of the Bootleggers is not to end the activity, but instead to profit from it, the Baptists might terminate their lobbying activity. If the Bootleggers believe that their Baptist partners will not stop until the activity, and hence the Bootleggers’ profits, are eliminated entirely, they might part ways. Yet the Garden seems to be a place where these details may be overlooked. Why? It is because many Baptists are realistic. They are willing to settle for a reduction of the unwanted activity because they recognize that a full cessation is unlikely through persuasion alone. Many Bootleggers recognize this and are thus willing to collaborate with the Baptists toward a full cessation that they feel confident will never come.

Unpopular restrictions on desirable human activities are difficult to enact and to enforce. By definition, it is almost impossible in the first place to convince people to willingly give up activities that they highly value (whether in the psychic or material sense),Footnote 2 let alone to support legislation restricting them. Enforced compliance is both expensive and obnoxious. Building the apparatus of detection and punishment soaks up resources, invites disobedience, and delegitimizes the enforcers. But a persuasive argument can not only increase voluntary compliance—thus obviating the need for some enforcement—but may even in the best case produce propagandizing and self-policing efforts by parts of the population, thus reducing compliance costs further. In other words, persuasive rhetorical arguments are inexpensive and they emit positive externalities: the reduction in the cost and the increase in the effectiveness of expensive and risky coercion. Together the Bootleggers and Baptists are more effective than alone.

So while they often work separately—though with unconscious parallelism—Bootleggers and Baptists can find a way to work together despite the obvious lack of meeting of the minds. They do so by creating a positive sum two-party game that capitalizes on their joint value. Simply put, the Baptist’s rhetoricFootnote 3 combined with the Bootlegger’s pragmatic manipulation of the political process makes legislation favorable to their joint cause more likely to be passed, less expensive to maintain, and profitable to both.

3.1 The Logic of Political Survival

In their influential works The Logic of Political Survival (2004) and The Dictator’s Handbook (2012), political scientists Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith developed a framework for understanding political choices and welfare outcomes in different polities. We selectively adopt and adapt their framework to examine the case of Bootleggers and Baptists political involvement in CAC regulation in the U.S.

According to the authors, attaining power is just the first step for the aspiring leader. Achieving the throne does not in itself confer the power to do whatever the new leader wants. Political leaders, from autocratic dictators to democratically elected presidents, must act to survive in the political environment. Once elected, the leader’s actions are determined first and foremost by his political environment and not by his civic-mindedness. In politics, altruism is a luxury good dearly bought.

In any polity there are people who are authorized to take part or advocate in the political process, and from whom at least tacit consent to political outcomes is required. This is the selectorate. These are the interchangeables (2012). They do not matter individually, only that they peacefully participate as a group in whatever capacity they have been granted. They allow, for example, for there to be a ruling family or for competing candidates on a ballot.

The influentials are the subset of the interchangeables whose consent to a particular candidate is necessary for that candidate to proceed to inauguration (2012). The influentials matter individually to the extent that their vote is counted or their support is recognized, but they are replaceable from the ranks of the interchangeables if the price is right. They decide the winner of the competition that the interchangeables have allowed. The influentials are the victorious group, formerly mere interchangeables, whose preference for a particular candidate, family, or other ruling entity has prevailed. Naturally they will expect something in return. The losing group of interchangeables will hope instead that the cost of their defeat is not too onerous.

Finally, there is the subset of individuals from whom aid and support is absolutely necessary to gaining and maintaining power, the essentials (2012). This can be a small subset of the influentials actually responsible for selecting acceptable candidates. Before you can win a competition you have to be in it, and the essentials get candidates onto the ticket in the first place. Their continued support is crucial to the long-term survival of the leader and they are expensive and difficult to replace.

Generally speaking, in a democracy, all eligible voters comprise the interchangeables. Their general consent matters but they are fungible. The influentials are the subset of the selectorate whose support will decide the contest (e.g., 50 % + 1 in the American system). Their turnout on polling day matters, and it comes with expectations. The essentials, or the winning coalition, are the even smaller number of critically important individuals, whether financial backers, political power brokers, or trusted confidants. To achieve and to maintain power, all leaders will have to devise a political strategy to satisfy each of these groups in return and in proportion to their usefulness. It is the relative size of the three groups that influences and helps to define the political strategy used to capture power, and the resulting political outcome.

3.2 Public and Private Goods

According to Bueno de Mesquita and Smith, the leader can choose to mix a bundle of two types of goods, Public and Private, to induce loyalty and support. Private goods are goods which can be enjoyed directly by individuals or small interest groups. These include a wide range from cash to privileges: a car, an Ambassadorship, or a commutation of a punishment. Private goods come with both positive and negative externalities. They are targeted and effective: valuable to recipients with very little wasted on those for whom receipt is neither necessary nor intended. This in turn encourages influentials to compete for the essential status. They are, however, expensive on a per recipient basis, and can induce resentment, especially in those who foresee no chance on the horizon of enjoying the benefits. Benefits, they remember, that were financed with their tax dollars.

Public goods are goods enjoyed by large portions of the polity, if not the nation at large. They might include things from local schools and monuments to interstate highways and the rule of law. Similar to Private goods, Public goods also contribute both costs and benefits to the leader’s calculation. On the one hand, they are expensive and not well targeted. Very often, essentials, influentials, and interchangeables alike enjoy these goods and services. But this is not entirely a defect. Such externalities enable the Public goods to be cost effective for large groups and are a palliative to the losing coalitions.

Because of these different and complementary features of Private and Public goods, the bundle that the leader distributes to society will contain a mixture of both. The ratio of Private to Public goods in the bundle will be defined by the relative distribution of the three groups, the essentials, influentials, and interchangeables, in the polity.

For example, in the U.S., hundreds of individuals and special interest groups are essential to finance the campaign, and tens of millions of votes are needed on election day to influence the decision, while the patient consent to temporary defeat is required of tens of millions more. Dictatorships are instead defined by the small number of essentials and influentials relative to that of interchangeables. When there are only a few members who must be satisfied with individual gifts, as in the case of a dictatorship, a leader must lean heavily on Private goods. As the number of these invested parties increases, e.g., in democracies, Private gifts become costly to apportion and thus the leader increases provision of public goods.

Bueno de Mesquita and Smith conclude that the prosperity generally enjoyed in democratic societies is a result of a larger ratio of spending on Public relative to Private goods; that this ratio is determined by the relative representation of key groups in the polity; and that all of this is put into practice by a leader constrained to do exactly that. In other words, it is not from the benevolence of leaders that We the People should expect our public goods, “but from their regard to their own interest” ([1776] Smith 1982).

And leaders are nothing if not self-interested. So for democracy it seemed to work out well enough for a while. But as Mencken famously put it: “Democracy is the theory that the American people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard” ([1916] Mencken 2009). The prosperity that came with the abundance of Public goods began to bear suspicious hybrid fruits when crossed with Private goods in the Garden. Just as a synergy between the qualities of Bootleggers and Baptists led to an unholy matrimony, a hybrid good taking on qualities of both Public and Private goods was soon cultivated.

3.3 The Hybrid Good

The framework developed by Bueno de Mesquita and Smith is very insightful. We add to their dichotomy of goods—Private and Public—to explain some essential aspects of strategic political behavior in modern American democracy. Specifically, we add to their framework the fruit of the Garden of Good and Evil—command-and-control regulations (CAC), the Hybrid good.

A CAC regulation contains the features optimal for a democratic leader seeking political support. It can take on the positive features of both a Private good and a Public good and, in some contexts, even minimize their negative properties from the perspective of the leader. For instance, the benefits of a CAC regulation can be targeted to some particular interest groups, and cause outsiders to compete for them as though they were private gifts. It can also provide to the leader the benefits of a Public good by conveying real or perceived benefits to a large number of citizens from across the political spectrum at a low per capita cost.

Unlike most traditional Public goods, CAC regulations are similar to the rule of law in that they do not have to be built out of the public purse. Building a dam is expensive; writing legislation is relatively cheap. The real cost arises after implementation and is usually too opaque and dispersed to be recognizable. Because CAC regulations are very complex, it may be difficult to know who is a winner and who is a loser, and what the ultimate ramifications of the policy will turn out to be. Very interested parties, the types who like to make themselves essential to the process, will not only understand the ramifications but will help to craft them. Rationally ignorant voters, on the other hand, whether influentials or interchangeables, will likely base their opinions on the carefully crafted rhetoric used to advertise the complex regulation, rather than on its real consequences. Thus, much of the cost of both Private and Public goods is eliminated while retaining many of the benefits of each.

Command-and-control regulation can be targeted to punish groups all the while carrying both the veneer of public spiritedness and an opacity that renders them almost immune to attack. For example, revised emission standards that place severe limitations on carbon dioxide discharge carry a heavy burden for electricity producers with lots of coal-fired plants, but place little burden on all producers that employ gas-fired and nuclear power plants. Buyers of electricity in the first case will face significantly higher prices, but will not likely be able to link the higher prices systematically to newly imposed emission standards. Meanwhile electricity consumers in unaffected regions can happily go forward without experiencing any inconvenience.

A command-and-control regulation may generate appropriable rents for those who benefit from its direct effects. For example, an air pollution control technology newly mandated for all firms in an industry imposes no cost on members of the industry that already use the technology. At the same time, the higher cost imposed on others limits industry expansions and leads to higher prices. All the while, interest groups that value cleaner air will celebrate the new rules even though it is impossible for them to measure changes in the amount of cleaner air that might be produced. Clean air lovers will encourage the regulators while often condemning industrial firms that continue to operate in the regulated environment. Of course, those firms that gain profits from the rule will celebrate too.

Not everyone will celebrate, however. Those who manage to recognize that they are hurt by the regulation, those who suffer the negative externalities such as higher prices or diminished opportunities and are able to make the connection to the CAC regulation in question, may be encouraged to join a coalition working against the rules that are imposing cost on them. But as long as the opportunity cost of collective action (either lobbying against the regulation or for an offsetting one) exceeds the cost imposed by the perceived harm, the harmed individuals will not act to change the status quo (McCormick and Tollison 1981). It is only harm in excess of the cost to avoid the harm that drives victims to defensive action.

Unlike the budget impacts of public works projects, which will have a listing of itemized costs in a government budget, regulations are born without clearly communicated cost estimates. The great advantage of the regulatory transfer mechanism is that it is difficult for all but those directly involved to truly understand its costs and effects. Indeed, regulations can become so complex that some who believe they are beneficiaries may only learn later that they have been hoodwinked. Consider for example, the U.S. requirement that ethanol be blended in all gasoline for allegedly environmental reasons. The ethanol blend diverts corn production away from food to energy, raising the price of both. Meanwhile, evidence accumulates indicating that burning ethanol blends are more harmful to the environment than unblended gasoline.

In spite of situations like ethanol, such regulations come with the claim that they are for a good cause, and thus their dual identity makes them an attractive choice for politicians who seek to garner political support while minimizing the political cost of their choice. Because of this dynamic, CAC regulations have taken root like weeds in the Garden of Good and Evil.

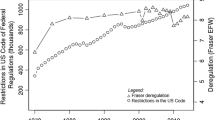

What about the extent of all this CAC activity? How burdensome is it? We know of no way to accurately estimate the economic cost of all CAC regulation, but we can offer a proxy for the growth of CAC by drawing on data produced by George Mason University’s Mercatus Center. The Mercatus Center has developed a regulation severity index that is based on an annual count, by industry, of the frequency of command-and-control words found in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulation, which is the final compendium of all current federal rules. Their RegData index counts the frequency of the words Must, Shall, May Not, Prohibited, and Required.Footnote 4 Figure 4 reports the results for six U.S. presidential administrations that include the first 6 years of the Obama administration. We note that Carter, Clinton, and Obama were Democrats; George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush, and Ronald Reagan were Republicans.

The data demonstrate that Republican and Democratic administrations alike, from President Carter to Obama, have continually added more and more CAC regulatory language to the books. Effectively designed, command-and-control social regulations can take this hybrid form that silently grants monopoly rents to some firms and industries while simultaneously, and loudly, providing a public good with the moral high ground. In other words, the successful CAC regulation tells the rent-seekers what they want to hear and what it wants the public to overhear.Footnote 5

We point out that in the Garden of Good and Evil, a perfect regulation may be seen as one that maximizes benefits to the elected leader’s essentials, advertises benefits to nonessentials, and maintains sufficiently disbursed or opaque costs to avoid resistance and effective rhetoric to reduce enforcement costs. Designing such subtle rules is by no means an easy task. Dressing private gifts in the cloak of public mindedness requires a team of expert tailors. The team consists of both the Baptists and the Bootleggers working to influence the regulation. Neither the Baptists nor the Bootleggers can achieve this effective regulatory provision when working alone.

3.4 The Bootleggers as Rent-Seekers in Consumer Markets

Recall that in our earlier discussion we described Bootleggers first as illicit sellers of alcoholic beverages in situations where state or federal law shut down the sale of those beverages on particular days of the week or entirely. The focus there was on a consumer good. In that situation, the Bootlegger is one who demands, in an economic sense, a restriction on the good—in order to become the monopoly supplier on either the legal or the black market. The more inelastic the demand is for the good, the more likely that people will continue its consumption despite the increased price or possible legal ramifications. That inelasticity of demand was an essential feature of what constituted a traditional Bootlegger zone of activity.

The U.S. regulation of tobacco illustrates the point (Yandle et al. 2008). Early federal regulation limited cigarette advertising and marketing practices, an action that enjoyed strong support from healthcare advocates and tobacco companies—with already highly developed brands and market share.

Still, while the Bootleggers and Baptists celebrated, no doubt in private for the Bootleggers, legislation arose that called for equal TV time for public health messages when tobacco companies advertised. As a result, major tobacco companies saw their sales fall. They were horrified. But then, the regulators called for a ban on all cigarette TV advertising. Healthcare advocates celebrated along with the Bootleggers once again as their profits rose in the face of hamstrung new competitors.

Consider now the case of marijuana prohibition, another consumer good for which there is a high inelasticity of demand. Marijuana growers and sellers have an incentive to keep marijuana illegal so that they can continue to reap the profits from its sale on the black market. Law enforcement and incarceration professionals prefer to sustain both the illegality and the use of marijuana—and thus a steady supply of “customers”—in order to protect their jobs. These are traditional Bootleggers. They prefer the activity ongoing but restricted, so that they can profit from the trade.

Rent-seeking Bootleggers, on the other hand, seek to profit off of a total prohibition by the sale of some substitute. Some representatives from the plastics industry, for example, keen on preventing the use of stronger and more durable industrial hemp fibers, have joined in the effort to ban marijuana. Additionally, producers of painkillers and nausea-reducing pills may support a ban in order to eliminate it as a substitute for their pharmaceuticals.

Here, in the case of marijuana prohibition, we have identified groups representing two types of Bootleggers: illegal producers and prison or law enforcement agents, representing traditional Bootleggers, and pharmaceutical producers and plastic groups representing rent-seeking Bootleggers. The Bootleggers cannot expect to prevail alone when lobbying for continued restriction of the production and sale of marijuana. Their hope comes in the form of Baptists with the moral high ground health, safety, and the common weal. If a majority can be convinced that it is harmful, dangerous, and tears the fabric of society, then they will consent and assist in, or at least tolerate, enforcement.

3.5 The Baptists: Idealists and Realists

With respect to the historical case of Prohibition in the U.S., our use of the term Baptists is meant to describe the type of people who struggled for the prohibition of alcohol on religious, moral, or ethical grounds. The term describes the true believers, those who believed that alcohol corrupted the souls of men and imposed high cost on American family life. In general, the Baptists power lies in their ability to “move men’s emotions” (Bongiorno 1930, 358) in a way that they become willing to change their behavior in alliance with a certain code of action—regulation—that satisfies the Baptist view of how the world should be organized.

The word Baptist in this sense has now become a metaphor for this brand of regulatory rhetoric, that is, the advocacy for the use of state power to enforce a prohibition or restriction on a good or activity in the name of justice or decency or social wealth maximization. We note that Baptist arguments for setting limits on an activity do not necessarily rely on scientific or logical justification. Indeed, Baptist groups are more inclined to argue that moral arguments trump scientific ones.

For instance, Baptist groups who oppose the use of any synthetic chemicals in the production of food may base their arguments on false assumptions, e.g., that the use of any dose of any synthetic chemical is equally toxic, that synthetic chemicals are more dangerous than natural chemicals, etc., even in the face of credible contrary evidence. The Baptist’s theories may not be scientifically sound, but logic and soundness are not the point, not if we are trying to understand how regulations come about and last on the books for decades in the real world. As Andrew Bongiorno correctly pointed out: “Theories of this kind may be absurd from the scientific point of view, yet a social scientist who views them not as absurd verbiage, but as social facts, cannot but recognize them as powerful determinants of the social equilibrium” (Bongiorno 1930, 358).

On a spectrum of regulatory stringency, we can divide Baptists into two types that deserve special scrutiny: those who desire absolute prohibition (i.e., maximal regulatory stringency) and those who will settle for some level of decrease in the quantity demanded of the particular activity. Let us call the first type the idealists and the second the realists. The Anti-Saloon League during prohibition is an example of the idealist Baptists. On the other hand, environmental groups worried about anthropogenic global warming who seek the reduction in carbon emissions but not its elimination are an example of the realists. The latter are satisfied with winning on the margin.

For example, a realist Baptist who would like to prohibit the use Bisphenol-A (BPA) in all plastic products would be willing to work with a rent-seeking Bootlegger industrialist who wishes to boost the sale of his Bisphenol-S plastic products by prohibiting BPA. While the realist Baptist’s desire for banning BPA is grounded in concerns over health and safety, he does not require the same ethical standards from the industrialist, who he may realize is merely interested in raising a rival’s cost. To a Baptist realist the end justifies the means.

The same is not true for an idealist, however. An idealist may only support the industrialist’s campaign if the industrialist’s rhetoric is a true reflection of his intentions. For example, an idealist Baptist might lobby for CAC regulation in the food industry along with a health food grocer who also sincerely believes that nonorganic foods are a danger to public health—and stands to profit handsomely from competition hampered by the proposed regulation. In this case, the boost to profits in the grocer’s sector would be a happy coincidence of action based on sincerely held convictions and a synergy of method.

Neither the idealist nor the realist, however, would knowingly join a traditional Bootlegger. Recall that a traditional Bootlegger is one who is not only hiding his true intentions (he has no moral qualm over the product at issue), but whose goal is ultimately to profit from the sale on the black market of BPA produced goods. Therefore, a necessary condition for coalescence of Baptists and the traditional Bootleggers, or Baptists and the rent-seeking Bootleggers, is agreement on the rhetoric for their policy position. In other words, both the traditional and the rent-seeking Bootleggers must publicly support the Baptists’ rhetoric if they desire the union to succeed.

Baptists can still achieve their goal by working with rent-seeking Bootleggers, even if at the expense of their preference for sincerity. Tragically, however, whenever the Baptists seek the same outcome as traditional Bootleggers they move further from their beloved goal and achieve the opposite of their intention. And in the world of transactional politics the result is always more pages in the Federal Register.

3.6 Collaboration as a Cost-Minimizing Technique

With political leaders eager to shower supporters with gifts in exchange for office, Baptist powers of persuasion and pragmatic Bootlegger power to produce regulatory copy provide a complete toolbox. We are left to show how their work reduces the production and maintenance costs of regulations.

The “profits” derived by consumers from conforming to the Baptist’s argument are ethical and moral in nature; they are not tangible or immediate like the benefits perceived from, say, taking a long, hot, guiltless shower. The nature of the profits advertised by Baptists to consumers means then that the rewards are extremely valuable to those who are convinced that they exist, yet worthless to nonbelievers. And even when morality is symmetric across individuals, their discount rate might differ dramatically. This is the heart of the reason why Baptists can never achieve full compliance on their own. They cannot prove to people, but instead must strive with great difficulty to convince them, that the value of their future rewards is worth the required present sacrifice.

The prospective profits of the traditional and rent-seeking Bootleggers, on the other hand, are readily convertible to cold, hard cash. This form of profit is perfect for greasing the wheels of favored legislation by filling the coffers of favored legislators. The grease being necessary since the Bootlegger obviously cannot advertise the personal profits and social costs associated with it—common understanding would either deliver the product stillborn or retard compliance and thus profit margins. The Bootlegger therefore relies on the political leader to enforce compliance in exchange.

The political leader also recognizes costs and risks involved with enforcing unpopular prohibitions. Enforcement without complementary rhetoric is expensive and labor intensive; in isolation the optimal level of compliance is not 100 %. And the power of the sword breeds resentment. Given the leaders’ desire to maintain office, he will not consent to such a deal; it is political suicide.

The presence, and sometimes the visible collaboration, of the Bootleggers and Baptists is necessary before an onerous CAC regulation can be passed, let alone consistently and efficiently enforced. Therefore, the leader is much safer to act after the Bootleggers and Baptists have formed a symbiotic coalition. The Baptists will convince the selectorate of “the ethics” of the regulation, and the Bootleggers will work to enforce it upon those who remain unconvinced. The environment has sent consistent feedback: successful attempts will be those that maximize compliance and minimize cost of enforcement.

4 Final Thoughts

In closing, we wish to make three points. First, regulations are vehicles for transferring resources by the way of transactional politics. To regulate is to assert a form of property right over a resource, or to rearrange existing property rights, or to create rights in previously “unowned” areas. In order for property rights to serve their purpose, they must be secure. So in order to gain the political support of the essentials and influentials, the aspiring political leader when seeking office must convince these vital parties that his offer is credible and will be secure against future repeal. Credibility rises with effective Baptist rhetoric in support of the Bootlegger enterprises, whether in unwitting or explicit coalition. Low Baptist engagement leads to low return on the political capital invested by Bootlegging interest groups in their effort to elect and maintain a friendly political leader. And, of course, if the Baptists leave entirely, for whatever reason, then the exposed Bootleggers lose their rhetorical cover and political footing.

Second, drawing on Public Choice logic and Bootlegger/Baptist theory, our chapter has offered an explanation as to why CAC regulation dominates the U.S. regulatory landscape. Critical to our story are hybrid regulations, those that provide appropriable private rents for Bootlegger interest groups and public good benefits for the Baptist influenced constituencies. Hybrid regulations reduce political transaction costs for any politician hoping to maintain political power. Our presentation of data on U.S. regulatory activity demonstrates that U.S. regulatory activity goes on unabated irrespective of the political party in power.

As a final point, what can we say about outcomes in the Garden of Good and Evil? Is there any evidence that CAC regulations generate more normatively evil than good or vice versa? Bueno de Mesquita and Smith predicted a positive monotonic relationship between economic activity and the more democratic a polity is as defined by the relative makeup of the essentials, influentials, and interchangeables (de Mesquita et al. 2004). The relationship seems to bear out—to a point. When adopting and adapting their framework to include hybrid regulatory provision and a Bootlegger and Baptist coalition we are able to better comprehend the growth of CAC regulation in the present incarnation of democracy in the U.S. and its potential deleterious effects. With the turn of every administration, different Bootlegger coalitions will get their turn to pull the lever.

It also is extremely difficult to provide a positive answer to the net benefit question because at the heart of weighing the good and the evil is an assumption of who’s good and who’s evil? Who is worth counting in the social calculus, and at what rate? Nevertheless, we will present two arguments, one empirical and the other theoretical, in an attempt to understand the outcome’s characteristics.

The first argument is Davies (2014a), who built on the RegData measure of regulatory stringency to study the effect of CAC regulation on the productivity of highly regulated enterprises and industries relative to those that carry a lessor regulatory burden (Davis 2014b, 11). Davies relied on the Bureau of Labor Statistics measure of production efficiency for 51 industries over the span of 14 years. He calculated relative regulatory stringency for each of the industries and then broke his sample of 51 industries into three equal parts, those heavily regulated, moderately regulated, and lightly regulated.

A ray of insight into this matter is provided in Fig. 5. When comparing growth in output per person, output per hour, and unit labor costs for two samples of U.S. industries—those most heavily regulated and those regulated least—across the years 1997–2010, we can infer that more frequent CAC regulation entangles production, leads to lower levels of output per worker and lower growth in income.

The second argument is that of Jane Jacobs’s as advanced in her seminal publication Systems of Survival: A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics (1993). Jacobs did not conduct an empirical analysis of welfare outcome; instead she studied the processes by which different outcomes emerge. She did so to infer the efficacy of outcomes from the processes generating them.

To Jacobs, there are two types of syndromes underlying the working of any society: one syndrome she names the “guardian syndrome” and the other she names “the commerce syndrome.” The guardian syndrome is based on the “taking” strategy of survival, a characteristic of the government sector and of Bootlegger methods. The commerce syndrome is based on the “trading” strategy of survival, a characteristic of the private, or voluntary, sector, and of Baptist methods. For any society to prosper both syndromes may be necessary, but it is crucial for them to remain separate. When the private sector, which is concerned with generating profits, trades its support of the government sector for exclusive grants of privilege, we get what Jacobs terms “monstrous moral hybrids,” which can yield stagnation by regulation.

Notes

- 1.

The ideas in this section originated in Shamoun (2013).

- 2.

People love to drink even though it may offer no material profit; people love to cash checks from their ownership stake in coal-powered electric plants, even though it may offer no psychic benefit.

- 3.

Baptists may be said to use threats/coercion, but not directly. They would refer to eternal damnation, or to catastrophic damage to the environment, or depletion of resources, etc., but these are always external theoretical threats and come as the result of having performed the activity itself, not threats of arbitrary force here and now with the purpose of preventing the activity from taking place.

- 4.

RegData is available at http://regdata.org.

- 5.

This conclusion is adapted from a line by Anthony de Jasay (1985, 7) in The State: “It seems to me almost incontrovertible that the prescriptive content of any dominant ideology coincides with the interest of the state rather than, as in Marxist theory, with that of the ruling class. In other words, the dominant ideology is one that, broadly speaking, tells the state what it wants to hear, but more importantly what it wants its subjects to overhear.”

References

Ackerman, Bruce, and William T. Hassler. 2008. Clean Coal, Dirty Air. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Adler, Jonathan, Andrew Morriss, Roger Meiners, et al. 2013. Bootleggers, Baptists and E-Cigs. Regulation. 38(Spring): 30–35.

Bernstein, Marver. 1977. Regulation by Independent Commission. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bongiorno, A. 1930. A study of Pareto’s treatise on general sociology. American Journal of Sociology: 349–370.

Boudreaux, Donald J., and A.C. Pritchard. 1994. The Price of Prohibition. Arizona Law Review 36: 1–10.

Brito, Jerry and Susan E. Dudley. 2012. Regulation: A Primer, 2nd edition. Fairfax, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

Buck, Stuart, and Bruce Yandle. 2002. Bootleggers, Baptists, and the Global Warming Battle. Harvard Environmental Law Journal 1(26): 177–229.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, and Alastair Smith. 2012. The Dictator’s Handbook: Bad Behavior Is Almost Always Good Politics. New York and London: Public Affairs.

de Mesquita, Bueno, Alastair Smith Bruce, Randolph Siverson, et al. 2004. The Logic of Political Survival. Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Davies, Antony. 2014a. More-Regulated Industries Experience Lower Productivity Growth. Mercatus Center at George Mason University. http://mercatus.org/publication/more-regulated-industries-experience-lower-productivity-growth.

Davies, Antony. 2014b. Regulation and Productivity. Mercatus Center at George Mason University. http://mercatus.org/sites/default/files/Davies_Regulation&Productivity_v1_0.pdf.

de Jasay, Anthony. 1998. The State. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund.

Jacobs, Jane. 1993. Systems of Survival: A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics. New York: Random House.

Kolko, Gabriel. 1963. The Triumph of Conservatism: A Reinterpretation of American History: 1900–1916. Chicago, Ill: Quadrangle Books.

McCormick, R. E, and R. D Tollison. 1981. Politicians, Legislation, and the Economy: An Inquiry into the Interest-Group Theory of Government. Boston; Hingham, Mass. In Distributors for North America, ed. Nijhoff, M. Boston: Kluwer.

Mencken, H.L. 2009. Little Book in C Major. South Carolina: Biblio Bazaar.

Pigou, Arthur C. 1920. Economics of Welfare. London: Macmillan and Company.

Shamoun, Dima Y. 2013. The Propensity to Truck, Barter, and [impede] Exchange: Democracy the Unknown Ordeal (Doctoral Dissertation, George Mason University). Retrieved from http://digilib.gmu.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1920/8756/Shamoun_gmu_0883E_10516.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Smith, Adam. 1982. An Inquiry Into THE Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Natilons. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Smith, Adam, Richard Wagner, and Bruce Yandle. 2011. A Theory of Entangled Political Economy, with Application to TARP and NRA. Public Choice 148: 45–66.

Stigler, George J. 1971. The Economic Theory of Regulation. Bell Journal of Economics & Management Science. 1: 3–21.

Wagner, Richard. 2009. Property, state, and entangled political economy. In Markets and politics: Insights from a political economy perspective, eds. Wolf Schäfer, Andrea Schneider, and Tobias Thomas, 37–49. Marburg: Metropolis.

Walsh, Bryan. 2012. How the Sierra Club Took Millions from the Natural Gas Industry—and Why They Stopped. Time, February 2. http://science.time.com/2012/02/02/exclusive-how-the-sierra-club-took-millions-from-the-natural-gas-industry-and-why-they-stopped/.

Yandle, Bruce. 1983. Bootleggers and Baptists: The Education of a Regulatory Economist. Regulation, 12–16.

Yandle, Bruce. 2010. National TV Broadcasting and the Rise and Decline of the Regulatory State. Public Choice 142(March): 339–353.

Yandle, Bruce. 2013. How Earth Day Triggered Environmental Rent Seeking. The Independent Review 1(18): 35–47 (Summer 2013).

Yandle, Bruce, Andrew P. Morriss, Andrew Dorchak, and Joe Rotondi. 2008. Bootleggers, Baptists and Televangelists. University of Illinois Law Review 4: 1225–1284.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Shamoun, D.Y., Yandle, B. (2016). Bootleggers and Baptists in the Garden of Good and Evil: Understanding America’s Entangled Economy. In: Marciano, A., Ramello, G. (eds) Law and Economics in Europe and the U.S.. The European Heritage in Economics and the Social Sciences, vol 18. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47471-7_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47471-7_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-47469-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-47471-7

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)