Abstract

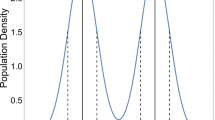

Studies in political economy, public choice, and political science frequently compare what politicians do with what their voters want. The textbook median voter framework serves as the central building block for numerous models of policy choice. Theories on the scale and scope of government, taxation, and redistribution regularly rely on the median voter model. It predicts that politicians converge to the preferences of the median voter due to the forces of spatial electoral competition and representation of the median voter is a stable equilibrium. Despite its theoretical appeal, empirical evidence strongly points against the convergence implied by the median voter model.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

The median voter model is elegant. However, to understand actual political behavior it is not sufficient. Time for political economist to get their hands dirty by digging deeper.

Studies in political economy, public choice, and political science frequently compare what politicians do with what their voters want. The textbook median voter framework serves as the central building block for numerous models of policy choice. Theories on the scale and scope of government, taxation, and redistribution regularly rely on the median voter model. It predicts that politicians converge to the preferences of the median voter due to the forces of spatial electoral competition and representation of the median voter is a stable equilibrium.

Despite its theoretical appeal, empirical evidence strongly points against the convergence implied by the median voter model. Findings from different sources show that legislative shirking is highly prevalent. If the median voter was decisive for policy choices, macroaggregates should correspond to the preferences of the median voter, which is not the case. Examining positions taken by politicians in the political space reveals that they diverge systematically from the median voter. Direct evidence for divergence comes from confronting referendum decisions with parliamentary votes on identical issues. When individual politicians’ actual policy decisions are compared to observed voter preferences in binding referenda, divergence from the median voter is the norm.

Numerous factors explain divergence and influence the behavior of politicians. They include candidate selection within parties, campaign contributions, difficulties in predicting constituent preferences, district characteristics and heterogeneity, entry of new opponents, incumbency advantages, individual characteristics of politicians, institutional constraints, interest group affiliations, multidimensionality of the policy space, partisan pressure and ideological purity, expected voter turnout, voter incomes, and winning margins, just to name a few. While these factors offer nonspatial explanations for failing convergence, they interact with each other, with the preferences of voters, and with the behavior of politicians: Candidates are selected by a party, making intraparty dynamics relevant, and selected candidates cannot credibly shift positions afterward, which leads to political alienation of the median voter and lower turnout. Thus, the fundamental workings of spatial electoral competition are affected by nonspatial factors. Theoretical research has mostly neglected to specify the conditions and institutional requirements under which the spatial explanation of the median voter model would or would not hold in the presence of diverse and competing incentives faced by politicians and voters.

The long-lasting appeal of the median voter model stems from its theoretical elegance, which makes it a great textbook case to focus ideas on electoral competition as one centripetal force. However, to understand actual political behavior and to predict policy choices reliably, the multitude of different incentives under changing institutions must be taken into account. Political economists will have to get their hands dirty to grasp politics more completely. Beautiful but overly simplistic theoretical models will not get the job done.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Stadelmann, D. (2017). Politicians Systematically Converge to the Median Voter. In: Frey, B., Iselin, D. (eds) Economic Ideas You Should Forget. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47458-8_57

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47458-8_57

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-47457-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-47458-8

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)