Abstract

There is an increasing attention on the morality of corporate tax strategies (CTSs) (Dowling 2014). Scholars argue for the need to include tax planning decisions in the analysis of an organization’s CSR profile (Dowling 2014; Sikka 2010; Scheffer 2013). Hardeck and Hertl (2014) provide initial evidence that consumers are willing to punish companies adopting aggressive CTSs and likely to reward responsible CTSs.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Purchase Intention

- Customer Relationship Management

- Political Ideology

- Negative Word

- Conditional Indirect Effect

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

There is an increasing attention on the morality of corporate tax strategies (CTSs) (Dowling 2014). Scholars argue for the need to include tax planning decisions in the analysis of an organization’s CSR profile (Dowling 2014; Sikka 2010; Scheffer 2013). Hardeck and Hertl (2014) provide initial evidence that consumers are willing to punish companies adopting aggressive CTSs and likely to reward responsible CTSs.

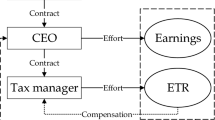

We extend this area of interdisciplinary research at the interface between taxation, marketing and CSR. We propose a model of moderated mediation that explains how individuals’ political ideology moderates the influence of different tax strategies on consumers’ reactions. Liberals, more than conservatives, perceive aggressive CTSs as unethical. Consequently, individuals on the left of the political spectrum are much more likely to react negatively and protest against companies engaged in aggressive tax planning activities. The study also questions previous research suggesting that responsible CTSs could have potential benefits to corporations willing to adopt them (Hardeck and Hertl 2014; Muller and Kolk 2012). In a sample of adults drawn from an online population from the USA, we find no evidence of beneficial effects in the adoption of responsible CTSs. Previous arguments overstate the potential benefits of adopting responsible CTSs.

Background

Aggressive corporate tax strategies (CTSs) are ‘efforts to minimize tax liabilities’ (Hardeck and Hertl 2014, p. 310). Conversely, responsible CTSs are perceived as in line with the intention of the legislator (Lanis and Richardson 2012). We study how stakeholders perceive aggressive/responsible CTSs that are reported by the media (Hardeck and Hertl 2014). Scholars suggest that stakeholders react negatively to aggressive CTSs (Cloyd et al. 2003; Hanlon and Slemrod 2009) because these practices are perceived as unfair (Hardeck and Hertl 2014; Antonetti and Maklan 2014). Consequently we hypothesize that consumers’ reactions to tax strategies are mediated by judgements of fairness.

It is also expected that liberals and conservatives will differ in their evaluation of the morality of CTSs. Liberals are most concerned with issues of harm and fairness (Graham et al. 2009). This moral intuition supports non-kin cooperation and solidarity (Haidt and Joseph 2004). Individuals who score high on the foundation of fairness consider equal treatment and the respect of general rules as particularly important (Graham et al. 2011; Jost et al. 2008). Aggressive CTSs are a direct challenge to the principle of mutual cooperation and equal treatment because they allow some companies to pay less tax than others (Weyzig and Van Dijk 2009) and less than what intended by the legislator (Dowling 2014). Aggressive tax planning contradicts a moral narrative important to liberals that focuses on the reduction of inequality through institutions that eliminate or reduce exploitation in society (Haidt and Joseph 2008; Smith 2003). It is also expected that, compared to conservatives, liberals would reward companies that engage in responsible tax planning. Moral foundations theory suggests that any positive impact should be stronger for liberals because the dimension of fairness is more important for them (Haidt and Joseph 2008; Smith 2003).

Finally we expect that consumers will reward companies engaging in responsible CTS and punish companies that are reported as implementing aggressive CTSs. These expectations are in line with recent findings (Hardeck and Hertl 2014). It is expected that this effect will be moderated by political ideology so that liberals will be much more likely than conservatives to punish (reward) organizations on the basis of their tax planning practices.

Methodology

We conducted two online experiments to test the model. In a three (CTSs: aggressive, responsible, control) × 1 (fictitious company profile)-between-subjects design, participants evaluated the perceived fairness of corporate behaviour, attitude towards the company, purchase intentions and intentions to spread negative word of mouth communications. All participants are recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk and we collected 149 and 150 complete surveys, respectively, in study 1 and study 2. In study 1, before evaluating the company profile, participants completed a scale measuring political self-identification. In study 2 political ideology is measured differently, through agreement with a set of policy topics.

Results and Discussion

In both studies, CTSs lead to differences in perceptions of unfairness (study 1, F(2, 147) = 38.55, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.52; study 2, F(2, 148) = 25.09, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.25), attitudes (study 1, F(2, 147) = 22.13, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.23; study 2, F(2, 148) = 14.99, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.17), negative word of mouth (study 1, F(2, 147) = 14.19, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.16; study 2, F(2, 148) = 25.09, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.13) and purchase intentions (study 1, F(2, 147) = 9.57, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.12; study 2, F(2, 148) = 8.68, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.10). Pairwise comparisons, however, show no evidence that responsible CTSs influence positively perceptions of unfairness or reactions towards the company. Consequently, we test our research model only comparing the aggressive CTS condition to the neutral condition. We use PROCESS (Hayes 2013, model 7).

Results are consistent with our research model. The conditional indirect effects demonstrate that liberals are much more critical than conservatives towards aggressive tax strategies. The manipulation has a strong indirect effect for liberals in terms of attitudes (study 1 effect: −1.83 CI from −1.66 to −0.92; study 2 effect: −1.39 CI from −2.00 to −0.91), negative word of mouth (study 1 effect: 1.66 CI from 0.84 to 1.52; study 2 effect: 1.89 CI from 1.25 to 2.66) and purchase intentions (study 1 effect: −1.30 CI from −1.26 to −0.59; study 2 effect: −1.01 CI from −1.67 to −0.48). On the contrary effects for conservatives are much smaller on all dependent variables such as attitudes (study 1 effect: −0.71 CI from −1.20 to −0.29; study 2 effect: −0.52 CI from −0.03 to −1.14), negative word of mouth (study 1 effect: 0.64 CI from 0.28 to 1.09; study 2 effect: 0.71 CI from 0.05 to 1.58) and purchase intentions (study 1 effect: −0.50 CI from −0.92 to −0.22; study 2 effect: −0.38 CI from −0.02 to −0.97).

We advance debates on the ethicality of aggressive CTSs and on their perception from consumers and other stakeholders. Reactions to tax avoidance are based on different psychological processes from those that explain personal tax compliance. Political identification, which is uninfluential in compliance decisions (Barone and Mocetti 2011; Bobek et al. 2013; Molero and Pujol 2012), regulates reactions to corporate tax strategies. Tax research needs to examine stakeholders’ reactions to CTSs as a separate field of study with implications for the psychology of CSR.

Using a similar design to Hardeck and Hertl (2014), we find no evidence that responsible CTSs offer benefits in terms of consumer reactions. This finding reinforces an emerging trend in consumers’ reactions to CSR: retaliations against irresponsible behaviour are stronger than rewards for responsible conduct. The differences in the results could be due to the fact that Hardeck and Hertl (2014) used a student sample, which is not best suited for the type of question they are trying to tackle. It is also possible, however, that results are due to the fact that different countries have different attitudes towards taxation (Alm and Torgler 2006; Richardson 2008; Tsakumis et al. 2007). Future research should investigate cross-cultural reactions to CTSs, since tax regulation is increasingly shaped within multistate arenas (e.g. OECD).

The results question whether companies can expect any benefit from responsible tax strategies. Aside from moral considerations, which encourage the adoption of fair tax planning procedures in all cases, responsible CTSs are important because they deter potential consumer backlash that is likely to be caused by aggressive CTSs (PwC 2013; Marriage 2014). Organizations whose customer base tends to include consumers with left-leaning political views need to be especially vigilant about the potential consequences of reports on aggressive CTSs. Finally, the study raises implications for organizations that are campaigning in order to promote more responsible CTSs (e.g. Tax Justice Network). The current social and political framing of tax avoidance makes it an issue primarily relevant for liberals. There is the opportunity in future campaigns to reframe the existing debates on tax avoidance so that they become more compelling for conservatives.

References Available Upon Request

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Academy of Marketing Science

About this paper

Cite this paper

Antonetti, P., Anesa, M. (2017). Political Ideology and Consumer Reactions to Corporate Tax Strategies: An Extended Abstract. In: Rossi, P. (eds) Marketing at the Confluence between Entertainment and Analytics. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47331-4_24

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47331-4_24

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-47330-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-47331-4

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)