Abstract

The idea of recovery has revolutionized our understanding of mental illness and its treatment, yet its meanings are diverse and it is invoked in many different contexts. This chapter systematically analyzes the idea, as it is used in contemporary mental health research, practice, services and policy, the scientific and social issues that fall under its rubric, the evolution of related ideas that results in the current state of affairs, and where that evolution may take us in the foreseeable future. The materials for this analysis include the scientific literature and scholarly discourse on recovery, law, regulation and social policy, discourse in the mental health professions and service industry, and popular media. The conceptual challenge for understanding the meaning of recovery is not one of definition so much as selection, determining which paradigm of recovery is most pertinent to which context or application or person.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Mental health administration

- Mental health policy

- Psychosocial rehabilitation

- Psychiatric rehabilitation

- Recovery

- Schizophrenia

- Serious mental illness

Introduction

The idea of recovery has revolutionized our understanding of mental illness and its treatment, yet its meanings are diverse and it is invoked in many different contexts. This chapter systematically analyzes the idea, as it is used in contemporary mental health research, practice, services and policy, the scientific and social issues that fall under its rubric, the evolution of related ideas that results in the current state of affairs, and where that evolution may take us in the foreseeable future.

Current Meanings

The Scholarly Literature

Our analysis begins with the data graphically represented in Fig. 1.1. A computer search of the behavioral science database PsycInfo, limited to journal articles, books and book chapters, for “recovery” and “mental illness” in the title, yields 167 unduplicated citations. The journal articles are distributed across 74 journals. This is not an exhaustive inventory of the scholarly literature, because not all relevant publications are indexed by PsycInfo, and many may not be captured by the search terms. Also, the search excludes doctoral dissertations, often harbingers of new trends in research. Nevertheless, it provides a reasonable sample for identifying patterns of change over time, and the abstracts provide enough information for a simple, face-valid categorical analysis of methodology and content.

After less than 10 citations over 60 years, there is a fairly linear increase beginning in the late 1990s, and peaking in 2012 (whether this is truly a peak or a continuation of a somewhat serrated but continuous increase is unclear—the 2015 total as of July is 14, but extrapolation to the entire year is unreliable—the extrapolated value of 28 would be an all-time high). In 2005, there is an increase of some 300 % over the previous several years. Taking the submission-publication time lag of scholarly journals into account, the spike follows publication in 2003 of the final report of The President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America (2003). Five of the abstracts in the PsycInfo sample mention the Commission, the first in 2005 and the most recent in 2012.

In his cover letter to President Bush, the Commission’s Chairman, Michael Hogan, succinctly identified the role of recovery in the Commission’s conclusions and recommendations: “After a year of study, and after reviewing research and testimony, the Commission finds that recovery from mental illness is now a real possibility” (President’s Commission 2003). The possibility of recovery from severe mental illness is a proposition that is evident in the previous scholarly literature, much of which will be discussed in this chapter, but with the Commission’s report, recovery became an acknowledged tenet of national healthcare policy. The year 2005 is the first to reflect the mental health scientific and policy community’s response to that development, and, for the purposes of the present discussion, conveniently serves to mark the beginning of the contemporary era of recovery-oriented mental health policy, research, and services.

Figure 1.2 shows the methodological make-up of the PsycInfo sample from 2005 until present, including the fourteen 2015 citations omitted from Fig. 1.1. For many veterans of mental health research, the most striking feature is the robust representation of original studies using qualitative or mixed qualitative/quantitative methods. This arguably reflects a more general increase in use of qualitative methods in behavioral and social science, but in addition, many researchers see the partly subjective nature of recovery, as it took shape leading up to the contemporary era, as especially well suited to qualitative analysis. About the same proportion of the sample is theoretical work—review of research and conceptual analysis concerning the idea of recovery itself, and implications for policy, research and practice. Next largest is new empirical studies, using psychometrics and other quantitative paradigms, of the nomothetic dimensions and longitudinal processes of recovery. The two smallest methodological categories are descriptions and/or pilot studies of innovative services or programs, and new controlled analyses or research reviews of service outcomes.

Figure 1.3 shows the topical distribution of the PsycInfo sample. The plurality of the publications is about services—treatment, support, and rehabilitation. Within that category, the largest subcategory is conceptual or theoretical discussions of the relevance to recovery of traditional or conventional mental health services, including the need for modification of content and clinical practice to make them compatible with recovery principles. This category also includes descriptions of innovative modalities or service packages not yet ready for controlled outcome trials, experimental and quasi-experimental outcome trials, program evaluations, analyses concerning the economics and dissemination of recovery-oriented services, and the training and education of practitioners.

There is not a single entirely new service modality undergoing controlled outcome evaluation in the entire sample. There are several descriptions and pilot studies of previously validated services being modified for specific subpopulations, e.g., elderly people, and accounts of one previously validated illness/wellness management skill training approach, reconfigured for group leaders who are self-identified people with mental illness and not mental health professionals, progressing through pilot studies and controlled trials.

Consistent with the methodological distribution, the next most represented topic is about the nature of recovery itself. This category includes research reviews and original empirical studies using both qualitative and quantitative methods. Subcategories include studies of types of roles and activities associated with recovery (occupational roles and activities, leisure activities, family roles) as well as broader attempts to identify a range of narrative themes and intrapersonal or phenomenological features that characterize recovery. A much smaller category, with both qualitative and quantitative original studies but no research reviews, is about features that may constitute important individual differences in the experience of recovery, including developmental characteristics, course of the illness, and experience with the service system, gender and cultural background. A few of these are quantitative modeling studies that attempt to identify trajectories and pathways leading to recovery outcomes.

Environmental factors that represent either barriers to or facilitators of recovery are the third largest category. These also include research reviews and original studies using qualitative and quantitative methods. Some focus on particular factors, including public attitudes toward mental illness, social support networks, and family characteristics. Others attempt to broadly identify facilitating factors and barriers.

The smallest topical categories are reports concerning development of specific instruments to measure the longitudinal course of recovery, either as a continuous process or a succession of stages, and studies of individual differences possibly relevant to recovery.

In summary, this simple analysis of the scholarly and scientific literature suggests that the past decade has seen new interest in recovery from mental illness, associated with canonization of that idea in national healthcare policy. The scholarly work divides itself into analysis of the recovery process itself, identification of environmental factors that facilitate or inhibit recovery, adapting existing treatment and other services to the new recovery-oriented context, and to a lesser extent, quantitatively measuring recovery and identifying individual differences in how people experience it. There is no evidence in the PsycInfo sample that scholarly interest in recovery has stimulated development of new types of treatment or rehabilitation, but there is considerable interest in how existing services and approaches should accommodate recovery principles. This includes modification of previously validated therapy and skill training modalities, adapting existing approaches to specific subpopulations, specialized education of professionals and other providers, inclusion of people with mental illness in development and testing of services, and provision of services by people with mental illness who are not mental health professionals. Outside the traditional domain of mental health services, there is considerable interest in policy and social interventions to make environments maximally conducive to recovery.

Healthcare Policy and Government

The milestone New Freedom Commission (2003) was preceded by a 1999 U.S. Surgeon General report that indicted the American mental health system for anachronism, inefficiency, and insensitivity to both scientific advances and consumer needs (U.S. Surgeon General 1999). The report also goes into great detail about the idea of recovery and its development, and discusses new treatment and other approaches needed to overcome the problems. Other federal actions that set the stage for canonization of recovery at the national level included the 1986 Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness Act, which extended federal funding to state agencies originally established to provide legal services and advocacy for people with developmental disabilities and their families. The 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) reflected broad public concerns about citizens with all kinds of disabilities. The 1992 ADAMHA Reorganization Act, which broadly reorganized the federal mental health bureaucracy, also brought the states into the policy and planning process, with a new system of block grants that made federal funding contingent on state-level planning councils whose membership includes consumers and family members. Attention to the needs of people with severe and disabling forms of mental illness, including the idea of recovery, began to appear in state-level policy documents describing best practices for that population.

The Surgeon General and New Freedom Commission reports were explicitly about two populations: adults with severe, disabling psychiatric disorders, historically diagnosed mostly as schizophrenia (dementia praecox before the 1930s), and children with such disorders, historically diagnosed mostly as childhood schizophrenia. These populations are named by two terms of art that had been in use since the 1980s in mental health policy and discourse, serious mental illness (SMI) for adults, and severe emotional disturbance (SED) for children.

In 2003 diagnostic practices for adults distinguished schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder, bipolar disorder, and severe, chronic depressive disorder, but all have in common an onset in adolescence or later, an episodic course (periods of better and poorer functioning), a psychotic presentation during episodes of exacerbation, and chronic, pervasive impairment at all or most levels of personal and social functioning. In the context of their historical analyses, both reports identified this SMI population as primarily those who were confined in psychiatric hospitals before the deinstitutionalization movement.

For children, the diagnosis of childhood schizophrenia has been abandoned, replaced by several others that still fall under the SED rubric. Generally, policy and practice in child mental health have changed as much as for adults. The child mental health industry is fairly distinct from the industry that serves adults with SMI, and the consumer and advocacy communities are fairly distinct. It is therefore difficult to draw parallels or distinctions between adult and child recovery, and a complete account is beyond the scope of this chapter. Hereafter, for the purposes of this discussion, recovery will mean recovery as experienced by those with adolescent- or adult-onset conditions, i.e., recovery from SMI.

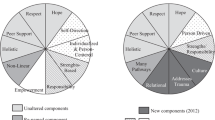

In 2004, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, which had replaced ADAMHA in 1992) sponsored the National Consensus Conference on Mental Health Recovery and Mental Health Systems Transformation, in collaboration with six other federal agencies. The primary purpose was to create a consensus definition of recovery. Participants included over 110 expert panelists, representing a wide range of stakeholders including consumers, family members, providers, advocates, researchers, academicians, accreditation organization representatives, representatives of the healthcare underwriting industry, state and local public officials, and others. Recovery from mental illness was defined as “a journey of healing and transformation enabling a person with a mental health problem to live a meaningful life in a community of his or her choice while striving to achieve his or her full potential.” Ten “fundamental components” of recovery were enumerated, and the list has since become ubiquitous in agency mission statements in the mental health services industry. The fundamental components include: self-direction, person-centered individualization, empowerment, holistic perspective, expectation of nonlinear progress, a strengths-based focus, peer support, respect, personal responsibility of the consumer, and hope for a better future.

The Public Forum

Public discussion of recovery is another important source of its contemporary meaning. The 1999 Surgeon General Report (pp. 92–98) identified several public organizations that have participated in the mental health policy discourse, beginning with Clifford Beers and the mental hygiene movement in 1908. The organizations include collaborations of citizens and professionals (e.g., Mental Health America, formerly National Mental Health Association), parents and families (e.g., National Alliance on Mental Illness, formerly National Alliance for the Mentally Ill), and self-identified people with mental illness. The last are further categorized as protest-oriented groups, whose members self-identify as “survivors” of psychiatry and/or an oppressive mental health system (e.g., Alliance for the Liberation of Mental Patients, the Insane Liberation Front), and self-help groups (e.g. Schizophrenics Anonymous, National Resource Center on Homelessness and Mental Illness).

The public discourse has not always been consistent with contemporary meanings of recovery. For example, NAMI’s founders were a generation who had suffered from the psychoanalytic theory of the “schizophrenogenic mother,” essentially attributing SMI to emotionally aloof parenting. Parents’ interest in destigmatizing themselves was unfortunately served by the biological reductionism of the so-called neo-Kraepelinian movement in psychiatry (Kutchins and Kirk 1997), which reduced schizophrenia to an incurable neurological disease. Attempts to destigmatize schizophrenia as an imagined character disorder backfired, because incurable diseases are even more stigmatizing (Deacon and Baird 2009; Deacon and Lickel 2009), and obviously inconsistent with recovery. The neo-Kraepelinian preoccupation with drug treatment was equally inconsistent with recovery. As the neo-Kraepelinian era gave way to modern neuroscience, and as self-identified people with mental illness gained membership on the NAMI Board of Directors, NAMI policies and positions became more consistent with recovery.

More recently the public discourse has been facilitated by development of the internet, especially the advent of web logs or blogs, essays and discussions posted on web sites, in which multiple discussants can participate over time. Blogs also create a convenient way to study the meanings of recovery associated with the public discourse. For the purposes of this discussion, the authors created a sample of internet websites consisting of the first 35 unduplicated results of a Google search, in July 2015, using the search string “mental health recovery blog,” excluding sites that do not actually include a blog page (mostly websites of mental health providers advertising their services). The resulting sample includes four government websites (11 % of the sample), sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA), the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and the White House. The NIMH and SAMSHA entries are actually a single cross-posted essay by a government official. Four websites in the sample are projects of private individual bloggers. Two (6 %) are associated with church or religious organizations, 3 (9 %) are from organizations broadly involved in social policy reportage and analysis (Rand, the Huffington Post, National Elf), four are the websites of nongovernment mental health service providers, and the remaining 19 (54 %) are associated with mental health foundations and advocacy organizations.

The information and discussions in the blogs cover a range of topics. Eighteen (51 %) include information or opinion about the nature of recovery and/or the conditions from which people are understood to recover. The conditions under discussion cover almost the entire range of psychopathology, including schizophrenia spectrum disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, post-traumatic disorders, and addictions, but not personality disorders. Twelve sites (34 %) include reportage and/or analysis of policy issues, including activities of government agencies and the economics and availability of services considered to be recovery-oriented. Nine sites (26 %) include information about professional services and programs, ranging from residential rehabilitation programs to advertisements for pharmaceuticals, explicitly or implicitly presented as recovery-oriented. These services also address a range of conditions, including psychiatric disorders and substance abuse. Twelve sites (34 %) offer specific advice about specific problems. The problems range from fairly ordinary mental health concerns such as the stress of daily life, to specific features of specific disorders, such as hallucinations and delusions. The advice ranges from changing one’s attitudes and beliefs, to seeking specific types of treatment, to using stress management and conflict reduction techniques familiar in the general psychological literature, to avoiding conventional mental health services and practitioners altogether. The sources or rationales for the advice include references to the scholarly literature, public education materials from the healthcare industry, familiar ideas from “pop psychology” or the “new age” movement, traditional religious principles, and personal experience. Six sites (19 %) include analysis and/or criticism of social policy, popular beliefs, cultural conventions and the healthcare industry, pertinent to facilitating recovery or creating barriers to it. Eleven sites (31 %) include personal narratives of illness or addiction and recovery, and four of those (11 %) are almost exclusively personal narratives.

Differentiation and Synthesis

Taken together, the scholarly activity, government policy, and public discussion about recovery portray both common and diverse understandings of its meaning. Since at least 2005, a key connotation of recovery has been a reform of the mental health system, the institutions it represents, and their dominant assumptions about mental illness. Chief among the targeted assumptions is that there is no recovery from mental illness. A close corollary target is the belief that this hopelessness reflects the basic nature of mental illness, not the failures of science, technology, the mental health disciplines, and/or the healthcare system. A second key connotation is that recovery is, most importantly, a subjective experience, the experience of the person undergoing recovery, not to be eclipsed by or subordinated to objective criteria imposed by others. Beyond these commonalities, the contemporary meanings of recovery are specific to particular theories of mental illness, types of mental illness, disciplines in healthcare and behavioral science, constituencies of healthcare service consumers, families and advocates, and segments of the mental health service industry. Nevertheless, the influence of the commonalities across the domains of science, policy, the healthcare industry, and public opinion, is such that in both the scholarly literature (e.g., Hamm et al. 2013) and the popular media (e.g., Wikipedia 2015) we speak of the recovery movement, a protean sociocultural shift for which the New Freedom Commission report is a useful orienting landmark.

The contemporary situation is reminiscent of Kuhn’s (1962) famous formulation of how science advances. Progress is not linear and gradual. It is punctuated by the rise and fall of dominant paradigms, unified bodies of knowledge and theory based on widely accepted assumptions. Research is a process of adding bits of information to the paradigm, and the progress of normal science is the gradual expansion of the dominant paradigm’s ability to explain and predict. However, as with the ancients’ terracentric solar system, in the course of normal science findings inevitably are generated that are inconsistent with paradigmatic assumptions. Eventually the paradigm collapses under the weight of unparsimonious and disconfirmatory evidence and a new paradigm replaces it. Before the new paradigm emerges, however, there is a period of instability, driven by competition among advocates for a diversity of alternatives. Today there is broad consensus about the need to reform healthcare in general and mental healthcare in particular. The idea of recovery connotes the need for reform (among other things), and the old obsolescent paradigm is usefully characterized by what recovery is not. We are no longer in a period of normal science guided by the old paradigm of mental illness, but its replacement has not yet emerged. In fact, it is not yet clear whether the old paradigm can be replaced by a single new one, or whether a multiplicity of new paradigms of recovery will be necessary to effectively guide science, policy, and practice.

The conceptual challenge for understanding the meaning of recovery is therefore not one of definition so much as selection. Which new paradigm of recovery is most pertinent to which context or application or person? A heuristically convenient starting point is the question, “what are the conditions from which people recover?” However, the revolutionary dimension of the recovery movement gives pause in approaching this question, because the categories by which we identify such conditions, including the diagnostic lexicon, are themselves elements of the old paradigm, and therefore suspect. On the other hand, there are enduring categorical constructs in psychopathology, and the mental health industry, and its supporting infrastructure (laws, regulations, professional guilds, consumer organizations, etc.) whose validity does not rest with canonization in a diagnostic manual. A complete understanding of the idea of recovery requires consideration of how those enduring categories shape its diverse expressions. An especially important example is the categorical distinction between SMI and substance abuse (SA).

Mental Illness and Substance Abuse

The need for extensive reform described by the President’s Commission and its predecessors was not limited to SMI services. The significance of substance abuse (SA) was acknowledged in the Commission report, but as an additional problem suffered by many people with SMI.

In a 2006 analysis of the American healthcare system, Burnam and Watkins (2006) noted that the evolution of SA concepts and treatments was quite distinct from mental illness. When alcoholism was incorporated in national healthcare policy by the Comprehensive Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Prevention, Treatment and Rehabilitation Act of 1970 (aka the Hughes Act, for its senate sponsor, Harold Hughes), there was already a services infrastructure evolved mostly through charitable and religious organizations, heavily influenced by the principles of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and its Twelve Step model. The founder of AA, Bill Wilson, testified before Congress in support of the Hughes Act. In 1973, alcoholism and other addictions with similar Twelve Step histories were brought together with mental health under the rubric of a single federal agency, the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration (ADAMHA). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) replaced ADAMHA in 1992, in the course of broader reorganization of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

There were historical tensions between the community that had created the SA infrastructure and the medical establishment, where research and treatment reflected mostly biomedical understandings of SA, less infused with spiritual or religious ideas and less committed to the principle of absolute abstinence as the only viable outcome (Burnam and Watkins 2006). Therapist credentials and related components of the SA infrastructure had evolved outside the traditional healthcare disciplines and guilds, sometimes creating an “anti-professional” climate. The authors of the 2006 analysis (Burnam and Watkins 2006) argued that this had not been particularly problematic for treatment of addictions, but there was a growing realization that addictions often occur in conjunction with other psychiatric disorders. Organizational boundaries, service funding channels, and the tensions between SA and mental health communities were significant barriers to joint treatment of SA co-occurring with other disorders. People with co-occurring disorders often “fell through the cracks” between the service systems. Similarly, there was a gross discrepancy between public funding of SA and mental health services, including a prohibition against eligibility for Social Security disability benefits (Supplemental Security Income, SSI) based on SA alone. The obvious solution is integration of services, but this is easier said than done. Most efforts to redress the segregation and disproportionate funding of SA have been carried out at the state level, e.g., through creative manipulation of Medicaid eligibility and funding streams, including new funding streams exclusively for co-occurring disorders.

There has been much progress in developing effective approaches for co-occurring disorders, but the results are unclear, and even troubling, with regard to recovery from SMI. On the one hand, there are many similarities and parallels between the idea of recovery as invoked by the New Freedom Commission and historical ideas about recovery from addiction. These were celebrated in a 2009 SAMHSA publication (Sheedy aand Whitter 2009) identifying all the key elements of recovery from SMI as equally applicable to addictions and co-occurring disorders. Subsequent SAMHSA publications (e.g., SAMSHA 2014) describe recovery without distinguishing between SA, SMI, or other disorders. The term “behavioral health” increasingly replaced “mental health” in agency names and policy language, to include SA and other psychiatric disorders under a common rubric in the healthcare regulatory infrastructure. Differences between recovery from SMI and recovery from co-occurring disorders were further obscured by changes in use of the term SMI itself, devolving from denotation of schizophrenia spectrum disorders and the historical psychiatric institutional population to include virtually any psychiatric diagnosis (Insel 2013). This was an economic boon to the SA services industry, because a co-occurring diagnosis makes more people with SA eligible for public funding of treatment.

However, an (arguably) inadvertent result was diversion of resources away from the SMI population. Since the beginning of the deinstitutionalization and community mental health movements it has proved difficult to incentivize community services for the SMI population sufficiently to recruit providers (Lamb and Bachrach 2001). Stretching the SMI category to include virtually any psychiatric disorder has exacerbated that problem. At the national level, this has generated pointed criticism of SAMHSA policy (Torrey 2015; U.S.G.A.O. 2014), even accusations of abandoning the SMI population. A recent case analysis of state-level consequences of national policy (Laib 2015) portrays a massive transfer of fiscal resources liberated by downsizing of state hospitals, to nongovernmental community providers who serve primarily the “co-occurring disorder” population while actively excluding individuals with SMI.

For people with SMI and SA, disability is generally most directly caused by the SMI, with SA in an exacerbating role. For people with co-occurring SA and non-SMI disorders, the disability generally is caused primarily by the SA. Integrated services for co-occurring disorders are generally joint provision of the separate treatments for SA and for the co-occurring disorder. Effective SA treatment for people with SMI is different in content and approach from treatment for SA or SA co-occurring with other disorders (Drake et al. 2004). Although the abstract principles of recovery may be comparably applicable, recovery from SMI is different from recovery from SA.

The term “rehabilitation,” closely associated with “recovery,” often appears in both the SA and the SMI literature and policy. However, in SA “rehab” refers to programs derived from Twelve Step or related models, and focused on detoxification and sustained abstinence, whereas in SMI it refers to psychiatric rehabilitation, a comprehensive approach combining psychosocial and biomedical components and derived from rehabilitation of physical disabilities (further discussed in a later section of this chapter).

A more complete analysis of the similarities and differences between recovery from SMI and from SA, co-occurring disorders or other mental health conditions is beyond the scope of this chapter. Hereafter, the present discussion of recovery will refer specifically to recovery from SMI, whether co-occurring with SA or not, but it is important to note that obfuscation of the differences, linked to attrition of resources for people with SMI, is an important issue in policy, research, and practice.

Evolution of Key Concepts

The understanding of recovery portrayed in the New Freedom Commission report, and elaborated in the subsequent decade, was a convergence of several key developments in mental health research, policy, and practice. Historical accounts trace these developments as far back as the moral therapy movement in seventeenth century Western Europe. For present purposes, the late twentieth century provides a sufficient perspective on how current meanings emerged.

Social Factors in SMI

In the 1950s and 1960s, sociological analyses such as those of Goffman (1961) stimulated public awareness that SMI is more than the intrapersonal processes postulated by both psychoanalytic and biomedical paradigms, dominant at the time. This complemented broader post-modern social criticism (e.g. Foucault 1961/2006) that identified mental illness as a kind of social role imposed by an exploitative culture on vulnerable and disenfranchised individuals. At a more individual level, experimental psychology also reinforced the idea that mental illness is at least partly the result of interpersonal processes. Analysis of the behavior of institutionalized patients using Skinner’s operant learning paradigm showed that it is shaped by rewards and punishments unsystematically meted out by direct care staff (Gelfand et al. 1967). The new methods of experimental social psychology revealed that patients’ understanding of their situation influences in turn the perceptions and judgments of their caregivers (Braginsky et al. 1969). These were highly counterintuitive findings at a time when the mainstream understanding of SMI emphasized irrationality and detachment from reality.

In the 1960s, the experimental findings were translated into a treatment approach, token economy, which effectively re-established adaptive social behavior in institutionalized patients (Ayllon and Azrin 1968). A decade later, in what was at the time the largest controlled treatment trial in the history of psychiatry (Paul and Lentz 1977), a treatment program based on token economy and related principles of social learning theory proved overwhelmingly superior to standard institutional treatment, not only in re-establishing personal and social functioning, but in leaving the institution for a stable community tenure.

Tragically, the successes of the early learning-based programs in psychiatric institutions were largely ignored. This is partially attributable to the deinstitutionalization movement of the 1970s, when most expected that institutional facilities would soon be nonexistent. In addition, analysis of the economics of the mental health industry (Magaro et al. 1978) reinforced the sociological ideas of the previous decade: mental illness, and by implication recovery from mental illness, is in large part an interpersonal process, recovery is not necessarily profitable for service providers, and effective recovery approaches are sometimes incompatible with the traditional power hierarchies of the mental health professions. This is echoed in the New Freedom Commission’s first principle for transforming the mental health system, which without such context may seem a platitude: “First, services and treatment must be consumer and family centered, geared to give consumers real and meaningful choices about treatment options and providers—not oriented to the requirements of bureaucracy.” Sadly, failure to realize this principle has been a major barrier to disseminating recovery-oriented practices and developing recovery-oriented services.

Today the legacy of earlier research on social factors is evident in the recovery movement, in its rejection of the limiting social role of “mental patient,” whether imposed by the service system, the patient’s family, practitioners, the culture at large, or the people with mental illness themselves. People in the “mental patient” role do not participate in community life. Participation in community life, a central value of recovery, includes participation in the community’s economy—not just the monetary economy, but the social and emotional economy as well, the myriad social contracts that give meaning to our lives. Social learning theory gives us a scientific perspective on those economies, how they are disrupted by mental illness, and how we can use them in pursuit of recovery goals. Mental illness does not obliterate a person’s ability to participate in economies, and with appropriate assistance and acquisition of key skills, such participation is within reach.

Just as important, absence of the economic benefits of community participation does compromise normal motivation to perform normal social roles. Recovery is most facilitated when the social environment provides incentives to reject dependent social roles, but the incentives must be engineered to be accessible to people at every stage of their recovery, in accordance with their abilities. A concrete example is the relationship between disability pensions and vocational functioning—when the former becomes a disincentive for pursuing one’s own work- and independence-related recovery goals, the system is not optimally recovery-oriented. Less concretely, this also means that interests within the mental health industry that benefit from the dependence and disability of its clients must be confronted and changed, at individual, organizational, and political levels.

Deinstitutionalization

Deinstitutionalization was itself a convergence of the sociological insights of the 1950s and 1960s, public concerns about conditions in state hospitals, the momentum of similar reforms in the developmental disability system, and the expectations of long-term benefits of the newly discovered antipsychotic drugs. In 1955, Congress had established the Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Mental Health, whose 1961 report became the basis of the Community Mental Health Act of 1963. The 1963 act set up the fiscal and regulatory infrastructure for community mental health centers, expected to serve the historical institutional population. The Surgeon General's and New Freedom Commission's historical analyses acknowledge the role of deinstitutionalization in creating a social context that was necessary for recovery to take on its current meanings (for repeated analyses of deinstitutionalization as it progressed, see Bachrach 1978, 1982, 1983; Lamb and Bachrach 2001).

In retrospect, deinstitutionalization involved a number of inaccurate and contradictory ideas about the nature of SMI. On one hand, the sociological and psychological studies showing the toxic effects of institutional environments gave the impression that simply escaping those environments would foster normal personal and social functioning. On the other hand, the belief that antipsychotic drugs would normalize functioning reflected a reductionist biomedical perspective, insensitive to social factors, and anathema to the contemporary recovery movement. Neither of the ideas were completely wrong, but by the 1980s it was clear that suppression of psychotic symptoms with drugs seldom leads to broader normalization. Instead of being absorbed into community life, formerly institutionalized people gravitated to “mental health ghettos” of substandard housing, exploitative landlords, minimal social services, high crime rates, and abject poverty. Ironically, the expectation that people could reintegrate in the community, if simply given access to medication and the conventional psychotherapy of the time, contradicted the persistent, widespread belief that SMI is an incurable, irreversible, and disabling disease. A “trans-institutionalization” process began, with an explosive increase in the representation of people with SMI in prisons and jails that continues as of this writing, although it may have peaked some time before 2010. (Deinstitutionalization itself was not necessarily the sole factor in the increase of people with SMI in prisons and jails. It may also be secondary to the differential impact on the SMI population of the overall increase in incarceration rates associated with the “zero tolerance” politics of the late twentieth century.)

Both successes and failures of deinstitutionalization set the stage for the recovery movement. The state hospital population was reduced by some 90 % nationwide, over the subsequent decades. However, less than half of the envisioned mental health centers were actually built, and none were funded sufficiently to serve the population. Of those that survived, most became more like publicly subsidized public practices, serving indigent populations with conventional mental health needs, not the historical institutional population. It was a foreshadowing of the contemporary “cherry-picking” process by which provider organizations tap into funding streams meant for people with SMI without serving people with SMI. Even when services were available, it became evident that neither medication nor the psychosocial treatment of the time was sufficient to help people in the historical institutional population regain normal functioning or have a decent quality of life. Even in light of the under-funding of the community system, more money alone would not solve the problems. New paradigms were needed.

Psychiatric Rehabilitation

The limited success of deinstitutionalization stimulated research to find more effective methods of treatment. William Anthony, a psychologist with a background in rehabilitation of physical disabilities, provided an organizing concept for much of this work in his landmark translation of rehabilitation psychology into the psychiatric context (Anthony 1979). At the conceptual level, the most revolutionary idea in psychiatric rehabilitation was that SMI must be seen not as a disease to be cured, but as a disability to be overcome. It was an idea that effectively competed with the reductionist expectation (gradually devolving to a fantasy) that eventually an SMI “wonder drug” would be discovered, and also with the public’s stereotype of people with SMI. Rehabilitation had gained respectful public attention in the aftermath of World War II, as wounded and disabled war heroes successfully returned to civilian life. It made sense to people that SMI is in important ways more like paralysis from a spinal injury than an infectious disease, and recovering from disability is different from curing an illness. Most importantly, it was obvious in physical rehabilitation that overcoming disability requires not only biomedical treatment, but psychological and socio-environmental levels of intervention as well. Hope, acceptance, determination, and support are critical for success.

The theoretical framework of rehabilitation psychology was social learning theory, derived from the ideas that had propelled the earlier work on token economy. In addition to its sensitivity to the social–-interpersonal context of behavior, social learning theory provided a powerful new idea about treatment: virtually everything that we do can be understood as exercising a skill that we have learned. Social roles are essentially sets of skills that we apply in the course of performing those roles. Accordingly, any “impairment” or “deficit” or “failure” in personal or social functioning can be understood as the absence of a needed skill set. People can overcome disabilities by learning new skills. Rehabilitation is a learning process. The learner is a student, not a patient.

Psychiatric rehabilitation prolifically generated new social learning-based treatment approaches and adapted others for use with SMI. The early principles of token economies were developed into more versatile and sophisticated approaches for community settings (e.g., Heinssen et al. 1995; Heinssen 2002; Liberman et al. 1976; Wong et al. 1986). The basic idea of skill training as a type of therapy led to social skills training, a structured approach to recovering interpersonal functioning (Corrigan et al. 1992; Liberman et al. 1975). Skill training led to other applications, including the skills required to self-manage one’s own psychiatric condition (Eckman et al. 1990, 1992; Liberman et al. 1986; Lukoff et al. 1986) and skills families could use to reduce conflict and effectively support their members with SMI (Mueser and Glynn 1995). Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), an individual psychotherapy approach based on social learning theory, which had proved effective for problems with anxiety, depression, and substance abuse in other populations, was adapted for SMI, and extended to include problems unique to SMI, such as delusions and hallucinations (Barrowclough et al. 2001; Haddock et al. 1998). The cognitive impairments of schizophrenia became targets for specialized treatment (Silverstein et al. 2009; Spaulding et al. 1999). Motivational interviewing, another individual therapy modality combining nondirective and CBT principles, was adapted to help stimulate hope and engage people with SMI and their families in the rehabilitation enterprise (Sherman et al. 2009). Comprehensive textbooks educated new practitioners as the approach evolved (Liberman 2008; Pratt et al. 2014; Spaulding et al. 2003). As the treatment array expanded and diversified, the idea of recovery remained an organizing principle and superordinate outcome goal. Psychiatric rehabilitation became a “tool kit” for pursuing individuals’ recovery goals.

Psychiatric rehabilitation is sometimes confused with psychosocial rehabilitation. There is considerable overlap, especially in fundamental principles related to recovery. Both eschew traditional biomedical assumptions about recovery and the primacy of medical treatment, and both emphasize the importance of functional dimensions such as social affiliation and work, in both subjective and objective domains. Psychosocial rehabilitation is historically associated with two organizations, Fountain House and Thresholds, in New York City and Chicago, respectively. Both organizations developed the clubhouse model, a living and working arrangement wherein groups of people help each other identify and pursue personal recovery goals (Macias et al. 1999). A version of a clubhouse model of psychosocial rehabilitation was developed in the Veterans Administration healthcare system, known as the Fairweather model after its founder George Fairweather (Fairweather et al. 1969). The psychosocial rehabilitation model predated psychiatric rehabilitation. By the time recovery was explicitly recognized as the key element in psychiatric rehabilitation (Anthony 1993), it had been so in psychosocial rehabilitation for over 40 years. Over time the particular principles and practices of psychosocial rehabilitation, including the centrality of recovery, became completely subsumed by the psychiatric rehabilitation rubric. In 1995, the pioneering Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal was renamed Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. By 2005, the professional organization International Association of Psychosocial Rehabilitation Services had spawned national affiliates, with the American one named United States Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association.

Locus and Focus

As the idea of recovery evolved in the late twentieth century, debates arose over some of its critical features. One such debate was about whether recovery could occur in institutional settings, and by implication, whether psychiatric rehabilitation could legitimately be provided there. In commenting on the debate of where rehabilitation and recovery can occur, William Anthony is said to have quipped, “It’s the focus, not the locus.”

There was never any debate about whether the coercion and loss of liberty in psychiatric institutions are incompatible with the values of recovery, but as deinstitutionalization progressed it became increasingly evident that state hospitals were not completely disappearing. In 2014, there were 207 state operated psychiatric hospitals nationwide, housing some 40,600 people (Haupt 2014). Deinstitutionalization did, for the most part, reduce the state hospital population to people who are consigned there through criminal courts (adjudicated “not guilty by reason of insanity”) or civil processes (civil commitment), but it did not eliminate those populations. The recovery-oriented psychiatric rehabilitation tool kit provides the most effective means of achieving discharge from a state hospital. Most individuals in state hospitals would endorse discharge as a high-priority personal recovery goal. Under these circumstances, denying the propriety of recovery-oriented services in institutions becomes abandonment of the remaining institutional population.

This debate had been mostly resolved by the end of the twentieth century, at least in the scholarly mental health community (Spaulding 1999), with the realization that recovery-oriented psychiatric rehabilitation transforms the role, mission, and processes of state institutions. Today the momentum of the discourse has shifted to the importance of the asylum role (Sisti et al. 2015), as opposed to the dubious presumption that the medical accouterments of a “hospital” provide anything other than a secure environment. Psychiatric rehabilitation has known effectiveness for helping people move from institution to the community (Silverstein et al. 2006). Nevertheless, dissemination of recovery-oriented practices in state institutions is still agonizingly slow, and the canard that “rehabilitation and recovery can only happen in the community” still appears as a gambit to preserve the unaccountability and sinecure of vested institutional interests (Spaulding et al. 2010), to the detriment of the mental health service system and its clientele (Tarasenko et al. 2013).

Psychiatric rehabilitation in long-term institutions or state hospitals is a different issue from treatment of SMI in acute or short-term “inpatient” settings. The inpatient time frame is too short for meaningful rehabilitation or recovery, but acute hospitalization may be a key starting point for both. Also, the context of short-term hospitalization can be made recovery-oriented. Research continues on maximizing the recovery orientation of hospital settings (Chen et al. 2013; Tsai et al. 2010).

Recovery Science: Objective and Subjective Domains

Recovery from SMI occurs in individual people, who subjectively experience the joys and sorrows of being empowered or disempowered, hopeful or hopeless, engaged or disengaged community members. People with SMI (and everybody else) also have very objective goals, e.g., living outside an institution, having friends, maintaining employment, being independent without a guardian or conservator. Achievement of objective goals is both impacted by and impacts people’s experience of empowerment, hopefulness, and engagement. Current research on recovery addresses both objective and subjective dimensions.

Closely related to the objective/subjective distinction is that between recovery as outcome versus process (Silverstein and Bellack 2008). Earlier in the evolution of recovery some saw this as two competing perspectives, the former of the scientific community and the latter of the consumer community. The Surgeon General report emphasized the need for services that produce better outcomes, and the New Freedom Commission characterized recovery as a journey. Contemporary research tends not to reflect a presumption of incompatibility, and both are assumed to be important, even “two sides of the same coin.” Nevertheless, recovery is complicated, and separate consideration of its objective and subjective processes and outcomes is necessary for heuristic manageability.

Prevalence of Recovery, Objectively Defined

A series of long-term outcome studies on people with serious mental illness was instrumental in the New Freedom Commission’s announcement that recovery happens. Generally, approximately 20–25 % of people show a return to essentially premorbid functioning levels, another 50–60 % of people achieve a substantial reduction in symptomatology and significant improvement in functioning levels, while approximately 20–25 % of people maintain significant symptoms and functional deficits (Silverstein and Bellack 2008). Some estimates put the percentage of people with “good” long-term outcomes at around 50 % (Bellack 2006).

The majority of the studies establishing prevalence rates of recovery were cross-sectional in nature. Harrow et al. (2005) conducted a 15-year longitudinal study in which they assessed participants at three-year intervals. Their results indicated that recovery is not linear, which is consistent with the episodic nature of serious mental illness. At least 41 % of their participants met their definition of “recovered” for at least one time point; however, very few met the criteria on multiple occasions. Overall, the presence of symptoms was negatively associated with functional recovery.

Considering the episodic nature of serious mental illness and recovery as an outcome, the value of concurrent research on more subjective components of recovery is clear. Theoretically, including a view of recovery as a process or journey, in which an individual becomes increasingly empowered to live a meaningful life while overcoming the challenges presented by mental illness, can mitigate the negative impact of symptom relapse or loss of objectively-defined “recovered” status. Furthermore, empowering mental health policies, such as shared decision-making and psychiatric advance directives, can help protect an individual’s progress by sustaining the recovery process even when objectively defined recovery suffers a setback.

Research on Personal and Environment Factors Impacting Recovery as an Outcome

When recovery is defined as an outcome, several domains are typically included (Bellack 2006). Symptom remission, as measured by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Score, the Global Assessment Scale, or being unable to meet diagnostic criteria, is typically one domain. Occupational functioning is typically another domain, represented through employment, both procurement of employment and often a threshold of hours per week required. The psychosocial functioning domain is evaluated through engagement in social relationships and participation in one’s community. Residential status and independent functioning in areas like money management are also considered domains, and evaluated as inpatient or institutional, supported living, or independent living. Finally, all of these domains must be maintained sufficiently for a period of time before recovery as an outcome is typically considered achieved. Time frames typically vary from a year to five years.

There is a significant amount of research investigating links between personal or environmental factors and the domains typically comprising the definitions of recovery as an outcome. While most environmental factors are identified through consensus as face valid (e.g.Silverstein and Bellack 2008; Onken et al. 2002; Young et al. 2000; Styron et al. 2005), there are a few that have been empirically supported. Access to comprehensive, coordinated, and continuous treatment, as well as a social network of supportive individuals who promote realistic expectations while supporting incremental progress, have been empirically supported as linked to better recovery outcomes (Silverstein and Bellack 2008; Kopelowicz et al. 2005; Liberman et al. 2002).

Chen et al (2013) developed a mental health staff competency profile, through interviews with consumers, family members, staff, and providers and amalgamated with information from a literature review resulting in a list of key competencies necessary for the provision of recovery-oriented services. Eight competency areas were identified: reducing environmental tensions (e.g., maintaining a therapeutic environment in an ordered inpatient setting), reducing personal tensions (e.g., empowering consumers to find ways to manage their health in their preferred ways), reducing providers’ own tensions (e.g., facilitating practitioners in their efforts to demonstrate a recovery orientation in daily practice), setting goals, and planning with consumers individually, engaging consumers in decision-making, fostering a positive recovery cycle, promoting recovery, and providing transitional services.

An alternative list of mental health staff behaviors was created based on their conceptual link to facilitating recovery in consumers, including developing a therapeutic relationship, conducting reliable symptom assessments and diagnostic evaluations, providing access to medical evaluation and treatment, completing functional assessments, empowering the individual, integrating psychopharmacology and psychosocial treatments, providing social skills training and family education, encouraging family involvement in treatment, providing access to transitional and supported employment, conducting clinical case management, and teaching consumers self-help and advocacy (Coursey et al. 2000a, b; Silverstein and Bellack 2008).

Brekke (2007) posited three environmental factors that are necessary for functional outcomes to improve, namely, opportunity, support, and enhancements. These were defined as options for functional capacity to flower into functional outcomes (e.g., affordable housing options to enable more independent living), a social support network of family, friends, peers, and staff promoting adaptive changes, and access to appropriate treatment and services that facilitate improved functional outcomes, respectively. All these socio-environmental factors had been operationalized in Paul and Lentz’ (1977) outcome study (discussed in the previous section of this chapter), and quantitatively measured by systematic observation of staff-patient interactions.

Another body of research has addressed personal factors that are linked to changes in the likelihood of achieving recovery as an outcome. Anxiety (Harrow et al. 2006) and a history of poor functioning (Schimming and Harvey 2004) are negatively related to recovery, and the latter is also specifically predictive of a worsening of negative symptoms over time (Schimming and Harvey 2004). Other individual factors related to more positive recovery outcomes include a shorter duration of untreated psychosis, good initial response to neuroleptics, adherence to treatment, supportive therapy with a collaborative therapeutic alliance, preserved executive cognitive functioning, verbal fluency, and verbal memory abilities, and a good premorbid history (Silverstein and Bellack 2008; Kopelowicz et al. 2005; Liberman et al. 2002). Early treatment is also significantly positively associated with better functional outcomes (Gearing et al. 2009).

Neurocognition is a more robust predictor of recovery outcomes than the presence or severity of positive or negative symptoms (Brekke and Nakagami 2010). Multiple deficits in neurocognition, including problems with memory, attention, language, and executive function, are found among the SMI population. Individual functioning can be divided into three levels: (1) functional capacity, defined as one’s ability to perform basic, daily tasks, (2) functional performance, defined as one’s actual performance of basic, daily tasks in the real world, and (3) functional outcomes, e.g., income and independence. Of these three levels, functional capacity seems to be most strongly influenced by cognitive functioning, while functional performance and functional outcomes are highly impacted by environmental factors. Social functioning is impacted by cognitive deficits in attention, memory, and verbal learning, while occupational functioning is impacted by cognitive deficits in memory, verbal learning, and processing speed, primarily. Independent living skills are most impacted by executive functioning deficits, as well as memory and verbal learning deficits.

Social cognition also has a significant impact on recovery outcomes (Brekke and Nakagami 2010). People with schizophrenia show multiple areas of impairment in social cognition, including social perception, social knowledge, theory of mind, attributional style, and perception of emotion, with the last being typically considered as the domain with the most impairment, on average. Deficits in social perception are associated with reduced functioning in social problem solving, social behavior, community functioning, and occupational functioning. Additionally, there may be an interaction between neurocognition and social cognition, so that while they both impact functional outcomes, their influence may not be entirely independent. For instance, early visual processing, verbal recognition memory, vigilance, executive functioning, and sensorimotor gating are related to perception of emotion and social perception.

Finally, another personal factor impacting recovery outcomes is motivation level. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia can impact motivation levels significantly through an individual’s experience of anhedonia, avolition, or amotivation. These three are demonstrated mediators between an individual’s symptoms and their recovery outcomes (Yamada et al. 2010). Additionally, other studies suggest that intrinsic motivation specifically is a mediator between cognitive deficits and recovery outcomes (Brekke and Nakagami 2010).

Research on Objective Recovery-Focused Outcomes

While a comprehensive review of the research on improving each domain typically included in a definition of recovery as an outcome could be compiled into its own book, a very brief review of relevant literature is included here, primarily to serve as an overview and a starting place for further study. Factors that predict symptomatic relapse include use of alcohol or drugs (Maslin 2003; Kopelowicz et al. 2005; Liberman et al. 2002), discontinuation of antipsychotic medications (Gitlin et al. 2001; Robinson et al. 1999), poor premorbid psychosocial function (Robinson et al. 1999), major life stressors, and an emotionally charged family environment (Butzlaff & Hooley 1998). Additionally, the development of group-based programs like Illness Management and Recovery (Mueser et al. 2002; Mueser et al. 2006), along with individual therapy, can be used to educate consumers on ways to manage symptoms and reduce the likelihood of symptomatic relapse while accommodating individual goals and encouraging empowerment (Bond et al. 2004).

There is a strong relationship between psychosocial functioning and the experiential process of recovery. Consumers report higher levels of engagement in their recovery process when they also have higher levels of social support and increased engagement in activities (Hendryx et al. 2009). The nature of the activity (e.g., social, physical, outside of the home, etc.) is not as important as the actual engagement in it, especially for those with lower levels of social support.

Employment is an objective outcome of substantial interest in the recovery movement, often studied in the context of supported employment, a psychiatric rehabilitation modality (Mueser et al. 2004). In supported employment, individuals with serious mental illness whose level of functioning would typically render them ineligible for traditional approaches to vocational rehabilitation (e.g., skill training or job counseling), are placed as regular employees in integrated settings where they work for pay but with ongoing support (Mueser et al. 1997).

In a project known as the “Hartford Study,” over two hundred clients with serious mental illness were randomly assigned to standard services, a supported employment model, or a psychosocial rehabilitation program using a more traditional approach to vocational functioning (Mueser et al. 2004). Participants in the supported employment condition had significantly better outcomes than clients in the other two settings, by being more likely to procure competitive work (73.9 %, compared to 18.2 % in the traditional rehabilitation condition or 27.5 % in the standard services condition) and more likely to procure any paying work (73.9 %, compared to 34.8 % in the psychosocial program or 53.6 % in the standard services condition). The results from thirteen studies showed similar findings, where 40–60 % of the participants did not find competitive employment, while less than 20 % of their counterparts did (Bond 2004).

While supported employment produces objective outcomes there are limitations. Although it is effective in creating access to desirable paid employment, it does not necessarily normalize vocational functioning (Mueser et al. 2004). In the Hartford study, only 33.8 % of participants in the supported employment condition eventually worked more than twenty hours a week. The average number of weeks worked per job was relatively low, the average amount earned was low, and half of the people who obtained jobs had lost them by the six month follow-up time point. Furthermore, it is currently unclear whether improved vocational functioning impacts the subjective experience of recovery. Some studies indicate that supported employment does not improve self-ratings of mood, life satisfaction, or self-esteem, while some indicate that it does (Silverstein and Bellack 2008). There is no evidence of a direct link between supported employment and better outcomes in other domains of recovery, such as symptom remission or social functioning (Bond 2004). Links between domains of objective and subjective recovery cannot be taken for granted.

Additional research has continued to improve the impact of supported employment. Several barriers have been identified including cognitive impairment, low educational attainment, depression, lack of self-confidence, and financial disincentives against increased income (e.g., disability pensions) (McGurk and Mueser 2006; McGurk et al. 2007). Outcome improved when supported employment was combined with occupational skills training (Wallace and Liberman 2004) or neurocognitive therapy (McGurk et al. 2007).

While reducing cognitive impairment is not often explicitly listed as a recovery outcome, cognitive functioning is strongly related to functioning in the areas that are explicitly listed (Kopelowicz et al. 2005; McGurk and Mueser 2006; Smith et al. 2004). Service intensity is predictive of functional improvement, but only when complimented by neurocognitive improvement (Brekke et al. 2009). Improvement of social cognition can improve the therapeutic alliance, which is related to both recovery as an outcome and as a process (Deegan 1996).

Neurocognitive therapy, aka cognitive remediation, produces objective recovery outcomes. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation found that its addition to other rehabilitation interventions improve cognitive and functional outcomes (McGurk et al. 2007). Other meta-analyses of cognitive remediation showed improvement in global neurocognition, as well as neurocognitive domains, such as verbal working memory (Brekke and Nakagami 2010).

Finally, there are a variety of assessment tools available to clinicians seeking to evaluate these levels of functional recovery in consumers (Mausbach et al. 2009). The assessments include topics such as social skills, medication management, independent living, and global functioning. They include clinician administered, self-report, and skill performance data gathering methods. These tools can be used to supplement the more facially valid outcome measures (e.g., maintenance of a job) to aid clinicians in assessing client progress towards recovery as an outcome.

Research on Subjective Dimensions of Recovery

Even when outcome research is inconclusive, social values must be incorporated into treatment design, and research shows negative outcomes when these values are neglected (Silverstein and Bellack 2008).

The Recovery Assessment Scale was originally developed from the narratives of consumers (Corrigan et al. 1999). A total of 41 items were produced for the measure, which provides a single score of recovery. The scale was then piloted on 35 individuals with a severe mental illness diagnosis and displayed test–retest reliability and internal consistency. The Recovery Assessment Scale was positively correlated with measures of social support, quality of life, self-esteem, and self-orientation to empowerment, and negatively correlated to psychiatric symptoms and age. A factor analysis was later conducted which revealed five factors, with 24 total items: (1) personal confidence and hope, (2) willingness to ask for help, (3) not dominated by symptoms, (4) goal and success orientation, and (5) ability to rely on others (Corrigan et al. 2004).

A similar instrument is the Mental Health Recovery Measure (Young and Ensing 1999; Ralph et al. 2000). This tool is based on six aspects of recovery: (1) overcoming “stuckness,” (2) discovering and fostering self-empowerment, (3) learning and self-redefinition, (4) return to previous functioning, (5) striving to attain overall wellbeing, and (6) striving to reach new potentials. These six aspects of recovery are put into a model with three stages: stage one involves the first aspect of recovery, stage two involves the second, third, and fourth aspects of recovery, and stage three involves the last two aspects of recovery. This measure is comprised of 41 total items that break down into six subscales that match the six aspects of recovery. There is excellent internal consistency for the total scale and a range of fair to good internal consistency for the subscales. The measures demonstrate convergent validity with the Community Living Skills Scales (Smith and Ford 1990) and with a measure of empowerment.

An alternative stage model of recovery, Stages of Recovery, is based on four themes: (1) finding and maintaining hope, (2) re-establishing a positive identity, (3) finding meaning in life, and (4) taking responsibility for one’s life (Andresen et al. 2003). These four themes are maintained across proposed five stages of recovery: (1) moratorium—a time of withdrawal characterized by a profound sense of loss and hopelessness, (2) awareness—a realization that not all is lost and that a fulfilling life is possible, (3) preparation—measuring strengths and weaknesses for recovery and beginning work on recovery skill development, (4) rebuilding—setting meaningful goals and taking control of one’s life, moving towards a positive identity, and (5) growth—living a full and meaningful life, characterized by self-management of the illness, resilience, and a positive sense of self. In this conceptualization of recovery stages, the fifth and final stage is also where an objective outcome of recovery is realized. The stages are intended to be sequential, but not necessarily linear or tied to specific timeframes to reflect the episodic nature of serious mental illness. A symptomatic relapse can occur at any stage without necessitating a return to an earlier stage, encouraging a resilient response.

The Stages of Recovery Instrument (STORI) measures movement through the proposed stages (Andresen et al. 2006). Ten themes were identified and then a conceptually valid item for each theme in each stage was developed, for a measure with a total of fifty items, with five stage subscales. Each item can be answered by selecting a response on a six point Likert scale, from “Not true at all now” to “Completely true now.” A mean score is calculated for each of the five stage subscales, and stage of recovery is determined by the highest mean score, with a tie going to the higher stage. There is also a positively correlated companion brief stage measure that allows consumers to self-identify their stage of recovery, Self-Identified Stage of Recovery (SISR). This scale is a single-item measure that has five sentences, one for each stage of recovery, and participants select the item they feel best corresponds to their stage of recovery. This SISR is positively correlated with the Recovery Assessment Scale, but negatively correlated with a self-report measure of psychological distress (Kessler-10, Andrews and Slade 2001) and with a clinician-rated report of psychiatric symptoms (Health of a Nation Outcome Scale, Wing et al. 1998). The STORI is positively correlated with time elapsed since last inpatient treatment, as well as mental health variables, including psychological wellbeing, hope, resilience, and the Recovery Assessment Scale.

While these tools are available to measure the subjective experience of recovery as a whole, there is a significant amount of research showing the independent importance of the common themes found in these subjective descriptions. One theme consistently present among descriptions of the recovery process is that of empowerment. People with schizophrenia often discuss their lives in terms indicating they do not feel a sense of agency (Lysaker et al. 2003). One component of a successful recovery process is being able to develop a narrative, attributing agency to themselves and interpreting life events in the context of a recovery process (Silverstein and Bellack 2008). Increasing the internality of perceived control over life events has been positively associated with recovery in schizophrenia (Harrow et al. 2009). At the very least, consumers reported that when empowerment was incorporated into the provision of mental health care, their motivation to be actively involved improved and their recovery progress increased (Cruce et al. 2012).

The idea of empowerment has many similarities to the idea of recovery. Neither has one single operational definition and both can be viewed as an outcome and a process (Swift and Levin 1987). Empowerment also often incorporates several of the other themes commonly identified as crucial aspects of recovery as a process, such as self-direction, individualized care, hope, holistic care, and strengths-based approaches (Rappaport 1981), as well as touching on the psychosocial domain of recovery as an outcome by encouraging community participation (Rappaport 1987). Measurements of empowerment are positively correlated with measurements of recovery orientation, and negatively correlated with internalized stigmatization of mental illness measures (Boyd et al. 2014).

One way in which empowerment is implemented is through the practice of shared decision-making. Shared decision-making involves the client using their knowledge about their lived experience with mental illness while the provider uses their knowledge about mental illness and its treatments to collaboratively develop, implement, and evaluate an individualized treatment plan (Deegan and Drake 2006; Corrigan et al. 2012). It moves beyond treatment adherence or compliance maximizing approaches to foster a truly mutual decision-making process. As such, shared decision-making is consistent with several of the recovery process themes often identified, such as individualized and self-directed care, self-responsibility, and holistic care (SAMHSA 2004). Shared decision-making can be used not only for medication management (Deegan and Drake 2006), but for the wide variety of decisions relevant to an individual’s mental health (Corrigan et al. 2012). Consumers involved in shared decision-making report higher levels of satisfaction with their treatment plan and providers, improved communication with treatment providers, increased perceived involvement in decision-making, and increased knowledge (Corrigan et al. 2012; Drake et al. 2009). Use of shared decision-making does increase later compliance with the treatment plan, although it may not directly change health decisions or behaviors of consumers (Corrigan et al. 2012).

Self-esteem, or some variation thereof, is also a common theme among definitions of recovery as a process. Self-esteem was directly related to subjective reports of recovery progress (Bell and Zito 2005) and self-esteem changes one year after hospital discharge predicted symptomatic severity (Roe 2003). However, some research indicates that if interventions solely target self-esteem, to the neglect of behavioral change, they do not have the desired outcome (Silverstein and Bellack 2008). This may be because self-esteem is generated through behavioral change, resulting in personal effectiveness (Silverstein and Bellack 2008).

However, response to behavioral change interventions may be improved by attending to self-esteem (Swann et al. 2007) and self-efficacy (Silverstein et al. 2006). This may be because self-efficacy is associated with more adaptive coping strategies (Ventura et al. 2004), while use of avoidant coping strategies can reduce self-efficacy (Vauth et al. 2007). Avoidant coping styles are also positively associated with symptomology (Wickett et al. 2006).

Strengths-based approaches have also been included as a common theme in recovery process definitions (SAMHSA 2004). Currently, there are some studies showing a strengths-based service delivery model may have some promise (Rapp and Goscha 2011). Although studies tend to lack an operationalized description of the intervention, there are some consistent aspects: service delivery is collaboratively developed and individualized to consumer strengths, primarily using existing community resources, and it takes place in the community. A recent meta-analysis of the relatively few available experimental or quasi-experimental designs testing this service delivery model revealed no significant differences for participants’ level of functioning or quality of life, but a significant preference for other service delivery models for improvement in psychiatric symptoms (Ibrahim et al. 2014).

Peer support is defined as the mutual support between consumers to encourage each other in recovery and bring about desired social or personal change (Solomon 2004; SAMHSA 2004). It can take a variety of forms, including peer advocacy, peer clubhouses, peer employment, or self-help groups (Armstrong et al. 1995; Roberts et al. 1999). One particularly interesting development from the peer support movement is the use of WRAP, or Wellness and Recovery Action Plans (Copeland 2002). WRAP is an illness self-management program that facilitates consumers developing an individualized plan to respond to their mental health symptoms, using personal resources and based on their preferences (Jonikas et al. 2013). WRAP sessions are typically conducted by peers who are in recovery from serious mental illness and specially trained in WRAP (Cook et al. 2011, 2014a, b). Consumers utilizing WRAP reported increased hopefulness, recovery, self-advocacy, and physical health, with a decrease in psychiatric symptoms; these changes were more pronounced for participants with higher engagement in the WRAP intervention (Cook et al. 2011, 2014a; Jonikas et al. 2013). Consumers also reported lower levels of anxiety and depression symptoms (Cook et al. 2014b). Additionally, implementation of WRAP was associated with a decrease in perceived need for behavioral health services, as well as a decrease in utilization of those services (Cook et al. 2013). It is not yet clear whether WRAP confers benefits comparable to or beyond those conferred by similar illness management skill training modalities designed for delivery by professionals.