Abstract

The aim of this chapter is to integrate the negative and positive perspective on intercultural interactions by implementing psychological theories, which can help to explain the inconclusive results of prior studies. Social identity theory, the similarity-attraction paradigm, and, yet to the lower degree, social dominance theory are theoretical underpinnings of the negative view of the relationships between culturally diverse individuals. The positives of intercultural interactions have been interpreted on the basis of information-processing theory and intergroup contact theory. Recently, the Positive Organizational Scholarship lens has been applied to cross-cultural research as well to foster the positive approach to cultural diversity. This chapter moves further, since it attempts to elucidate intercultural interactions at work by referring to the theories that have been rarely implemented in cross-cultural studies so far. Thus, Bandura’s social learning and social cognitive theory, thriving, the Job Demands-Resources model and the transactional theory of stress are shown as the theoretical framework for the discourse.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Information-processing theory

- Intergroup contact theory

- Positive cross-cultural scholarship

- Positive intercultural interactions

- Positive Organizational Scholarship

- Similarity-attraction theory

- Social dominance theory

- Social identity theory

- Social cognitive theory

- Social learning theory

- The Job Demands-Resources model

- Thriving

- Transactional theory of stress

1 Introduction

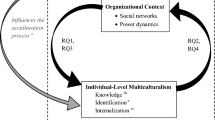

Due to globalization, multinational companies (MNCs) have become an inherent element of the world economy. They are considered to be multicultural spaces since they consist of members, who represent various, frequently very distant national cultures. As a result, those individuals are involved in intercultural interactions. They face serious challenges caused by cultural diversity, thus, not surprisingly, the negative view of contacts among members of different cultures have dominated prior studies (see e.g. Hernández-Mogollon et al. 2010; Luo and Shenkar 2006; Rozkwitalska 2012; Sano and Martino 2003). Nevertheless, such relationships may be positive and frequently contribute to individual, group and organizational success. Hence, recently some authors have also attempted to investigate the positive outcomes of employee cultural diversity (e.g. Dikova and Sahib 2013; Mannix and Neale 2005; Roberge and van Dick 2010; Stahl et al. 2010; Stahl and Tung 2014; Stevens et al. 2008). This positive perspective in the literature and research still requires better documentation and explanation, especially if MNCs and the working relationships of their subsidiaries’ staff are considered. As claimed by other scholars (Stahl et al. 2010; Stahl and Tung 2014), prior research is biased, since the negative view prevails in research and still much less is known about the positives of intercultural contacts than about the problems. Thus, more effort is needed to explain the phenomenon of intercultural interactions at work (Shore et al. 2009).

The chapter responds to the above calls. Its aim is to integrate the negative and positive perspective on intercultural interactions by implementing psychological theories, which can help to explain the inconclusive results of prior studies. First, it provides an overview of theories that have been applied in prior research to explore intercultural interactions. Then, it offers a look at intercultural interactions from the Positive Organizational Scholarship lens. Afterwards, it also attempts to integrate the negative and positive perspectives on cultural diversity by implementing psychological theories that can help to explain inconsistencies in previous studies. Finally, conclusions, contributions and directions for future research are put forward.

2 Theoretical Underpinnings of Intercultural Interactions’ Outcomes

2.1 Intercultural Interactions as “Double-Edged Sword”

2.1.1 The Problem-Focused View on Intercultural Contacts

The more traditional, problem-focused view of cultural differences among people emphasizes that such differences pose barriers to performance and are a kind of a liability, leaving “managers in multinational teams and companies discouraged about their chances of achieving potential synergies” (Stahl et al. 2010, p. 440). This perspective holds that the distance and novelty embedded in intercultural interactions are source of incompatibility, consequently leading to discordance, frictions and conflicts (Stahl and Tung 2014).

Social identity theory, further extended by self-categorization theory (Tajfel and Turner 1986), is by far the most influential theoretical perspective, which has been adopted in research to explain the dynamics of multicultural staff and problems caused by multiculturalism in organizations (e.g. Coates and Carr 2005; Cooper et al. 2007; Loh et al. 2009; Lauring and Selmer 2012). Its central assumption is that people define who they are in terms of their group membership (in-group) and, in parallel, in relation to another group (out-group). Moreover, each human being wants to hold a positive self-image. Groups give individuals a sense of belongingness and satisfy a need for self-esteem. People classify others into groups, which accentuates the differences between groups and similarities inside the in-group. As a result, a person is seen as a group member rather than as an individual, which fosters a stereotypical view of others. In the process of social identification, individuals identify with one or more groups to which they belong and their self-concept is being created. In order to maintain a positive self-image the social comparison process ensues, where in-groups need to be compared favorably with out-groups. If the value of others is diminished, it may lead to prejudice and discrimination toward them. As a result, “intergroup interaction and communication become more difficult as members consciously draw a wall or boundary between themselves and the people they consider as outsiders” (Loh et al. 2009).

Taking into account that individuals are members of various groups (e.g. professional, organizational, national, etc.), especially in the context of MNCs, it is not clear which of the identities will be the most salient in shaping their behaviors (Hogg and Terry 2000). For example, working in MNCs may create a new basis for self-categorization and build among employees the identity of being a member of an exceptional diverse team or organization and belonging to a brand new class of labor force. Furthermore, speaking foreign tongues, different language proficiency levels among MNCs’ staff and even a choice of media used in communication in intercultural interactions can also be sources of categorization (Lauring and Selmer 2011; Klitmøller et al. 2015). Such overlapping group memberships in MNCs may result in social identity complexity, which reflects that “an outgroup member on one category dimension is an ingroup member on another” (Brewer and Pierce 2005, p. 430). Prior research demonstrates that this reduces the significance of any of multiple identities of a person and contributes to more favorable attitudes toward multiculturalism (Brewer and Pierce 2005; Freeman and Lindsay 2012).

Similarity-attraction theory (Byrne 1971) posits that a similarity of attitudes, values, beliefs, personality characteristics, social status, habits and even physical attributes facilitates interpersonal attraction and liking. Such similarity provides corroboration that a person’s opinions, views, values, etc. may be correct, since others share them. Furthermore, knowledge of similar attitudes can enable individuals to predict others’ behaviors and has rewarding consequences by reducing uncertainty in interpersonal relationships and providing comfort and confidence. People’s need for social validation compels them to compare themselves to others and to like similar others. “Liking and similarity reinforce one another and create a strain toward symmetry. People will avoid communicating with those they dislike or with those who hold opinions or views differing from their own as a means of reducing the strain produced by the disagreement” (Mannix and Neale 2005, p. 39). Similarity helps to create a sense of belongingness and self-image. The paradigm allows for the assumption that surface-level differences will imply differences in underlying attributes, since they serve as “a “proxy” for a set of experiences that can lead directly to the formation of specific attitudes” (Mannix and Neale 2005, p. 40). On the basis of the similarity-attraction paradigm it can be inferred that people experience more cohesion and social integration and their relationships manifest more trust and reciprocity in a homogenous group than in diverse ones (Li et al. 2002). Therefore, cultural differences in MNCs will not be attractive because they exhibit a lack of similarity among their employees and consequently a lack of liking. Dissimilarity may additionally result in poor communication, conflicts, decreased satisfaction, barriers to knowledge sharing, process loss, discrimination, etc. in intercultural interactions (Stahl et al. 2009; Lauring 2009; Lin and Malhotra 2012; Mamman et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2012). The research of van Veen et al. (2014) and van Veen and Marsman (2008) also suggests that similarity is a matter of importance in hiring international board members in European companies, including MNCs, and the national diversity of board members is not high among European MNCs. Nevertheless, with regard to the theory, it is also worth mentioning that people with a high need for uniqueness may find similarity to be threat to their distinctiveness, i.e. the self-other similarity can be aversive (Snyder and Fromkin 1980). Accordingly, diversity will be more attractive than similarity, which has already been noted in prior studies. For example, Stahl et al. (2010) imply that working in a multicultural environment may satisfy a person’s need for variety and some people express great curiosity about cooperation with people from other cultures.

In studies on working in a multicultural environment social dominance theory has been applied to a relatively limited number of works (e.g. Carr et al. 2001; Coates and Carr 2005; Magier-Łakomy and Rozkwitalska 2013), mainly in the context of migration. However, it may offer additional theoretical underpinnings about barriers in intercultural interactions. The theory allows the assumption to be drawn that the country-of-origin of a person may impact how s/he is perceived by locals. Namely, individuals from less socio-economically dominant countries are likely to suffer from prejudice and their professional competence will be evaluated as lower. The personality traits known as social dominance orientation, drawn upon the theory, predicts prejudice in interpersonal contacts (Leong and Liu 2013; Harrison 2012).

2.1.2 Positive View on Intercultural Interactions

The positive perspective on intercultural contacts, while it seems useful for increasing effectiveness of multicultural staff, is remarkably less common in research (Stahl et al. 2010; Stahl and Tung 2014). Stahl and Tung (2014) demonstrate that current theory and studies are too problem-oriented and overemphasize the liabilities of cultural differences. In particular, scholars focus too much in their theory building endeavors to expose potential difficulties, while prior research reveals a more complex or mixed picture. Nevertheless, Stahl and Tung (2014) noted a slight trend towards decreasing negativity over time in the theoretical assumptions regarding intercultural contacts. Still, they rather did not observe such a trend in the empirical papers they analyzed.

The positive view on cultural differences among staff has been substantiated by information-processing theory. Intergroup contact theory also contributes to understanding of the positives in intercultural contacts.

On the basis of information-processing theory interactions in groups can be seen as information processors, whereas the way information is used affects group performance. Individuals acquire information from interactions with their surroundings, including others, while the context, in which they function, delivers a processing objective. Their individual capacity for information-processing is limited, thus they pay attention only to certain information while ignoring other information. The processing of information results in a response, which includes decision making, inference, forming an opinion or solution. The information processing phases, i.e. attention, encoding, storage and retrieval, are of vital importance here (Hinsz et al. 1997). The theory and research based on it make it possible to imply that the deep-level sources of cultural diversity of the workforce, since it offers access to individuals that operate in various personal networks, are from different backgrounds, use their unique sources of information, experiences, mental models, cognitive perspectives, and have differentiated expertise and skills, influence all the information-processing phases. The different perspective that people bring to the group can even impact processing objectives as well as how much information is heeded. The cultural diversity of staff affects the interactions among them and the way of approaching the same cognitive task (Hinsz et al. 1997). It may also prevent groupthink and boost the capacity for creativity and innovative problem solving, because diverse individuals manifest greater inclination to examine the problem at hand thoroughly. It stimulates deeper analysis and provokes constructive conflicts. Further, it may contribute to synergy and improve the performance of a group. These positive outcomes can be attained if multicultural staff bring deep-level elements of cultural diversity to the fore and exhibit an openness to them (Stahl et al. 2010; Stevens et al. 2008; Mannix and Neale 2005; Lauring and Selmer 2012).

Intergroup contact theory posits that the more contact people have with dissimilar others, the more positive their attitudes toward them will be, because intergroup contact reduces prejudice. Frequent and extensive contacts between groups diminish stereotypical perception of outgroups, help people to see similarities among people, which activates liking (in accordance with similarity attraction paradigm) and improves reciprocal relations (Pettigrew and Tropp 2008). Prior research identifies facilitators of positive intergroup contacts such as equal group status within a situation, a clear common goal, cooperation or interdependence between groups and the support granted by the authorities, by law or by custom (Roberge and van Dick 2010). Moreover, Leong and Liu (2013) indicate that intergroup contacts foster positive intercultural interactions when such contact occurs in “an equitable, intimate, and non-threatening environment” (p. 659). Some scholars also refer to the idea of common in-group identity as an enabling factor in intergroup contacts that require the creation of a salient, attractive superordinate category, which is to replace prejudice in favor of identification at the superordinate level (Brewer and Pierce 2005). In case of MNCs this may indicate the need to establish a common organizational identity. Still, interpersonal contacts between outgroups are a prerequisite of prejudice reduction, which in a multicultural work environment can be easier, since employees are motivated to foster relationships with diverse others due to common goals. A positive intercultural climate can also stimulate intergroup contacts and improve mutual relationships (Luijters et al. 2008).

2.2 Positive Organizational Scholarship and Positive Intercultural Interactions

Among other factors, Positive Organizational Scholarship (POS) has recently inspired scholars to look at the bright side of cultural differences among individuals (Davidson and James 2009; Stahl et al. 2010; Przytuła et al. 2014; Rozkwitalska et al. 2014; Rozkwitalska and Basinska 2015a, b; Youssef-Morgan and Hardy 2014; Stahl and Tung 2014). POS is an emergent field of study in the organizational sciences and it especially focuses on the positive effects and attributes of both organizations and their members. Scholars concentrated on POS attempt to unravel how various organizational dynamics produce positive or unexpected outcomes. Interactions as a specific type of relationships are seen as explanatory mechanisms that can generate beneficial effects, e.g. creativity or satisfaction (Cameron & Spreitzer 2013). In the view of Stahl and Tung (2014), POS may help to redress the imbalance in studies on intercultural interactions and explain the “double-edged sword effects” in previous research. They also postulate that new theoretical models should be built to examine the positive aspects of cultural differences and account for the mixed effects reported in earlier works. This section and the next one respond to their calls.

In more traditionally-oriented studies intercultural interactions are defined as effective if the interacting people exhibit good personal adjustment, namely contentment and well-being, develop and maintain good interpersonal relationships with one another and effectively achieve task-related goals (Thomas and Fitzsimmons 2008). POS may broaden the research perspective on intercultural interactions. It allows looking at them twofold, as high-quality connections and positive work relationships. While connections refer to interactions that are momentary and short term, relationships are enduring and lasting. High-quality connections are marked by vitality, mutuality and positive regard. Despite their momentary and short term features, they have a lasting positive influence on people and organizations as they enhance, for example, organizational commitment and foster learning and growth (Wayne and Dutton 2009). Positive work relationships are mutually beneficial to the involved parties, which means that they include positive states, processes and outcomes. Like high-quality connections, the attributes of positive work relationships are vitality, mutuality and positive regard, yet they are subject to changes and are longer lasting. Research demonstrates that the quality of work relationships makes a difference in such key outcomes as e.g. satisfaction, commitment or performance (Kahn 2009).

Intercultural interactions involve multiple forms of contacts among people from different cultures, from momentary to enduring and short term to lasting ones (Molinsky 2007). Davidson and James (2009) ascertain that it “is this attitude of learning about the other that is critical in building strong and sustained positive relationships across difference” (p. 138). They should also be marked by vitality, mutuality and positive regard, and if accompanied by reciprocity, intercultural interactions will result in positive social capital (Wayne and Dutton 2009). Positive intercultural interactions should therefore have several core features. First, the interacting parties need to manifest authentic affection and positive regard for one another. Second, they have to be open to ongoing learning. Third, people in intercultural interactions should manifest engagement despite the challenges encountered in such relationships. Finally, the interactions have to lead to effective work, careers and development, i.e. produce positive outcomes (Davidson and James 2009). Learning, as a critical antecedent of positive intercultural interactions, occurs when a person interacts with others whose values, perspectives, approaches to problem solving, etc. differ from those that s/he presents. Drawing upon social identity theory, Davidson and James (2009) infer that individuals in intercultural interactions are faced with conflict, which is experienced due to expectations held about others. Transforming the experienced conflict into learning can further positive relationships. Nevertheless, it depends on whether persons are sufficiently invested in the relationships and are able to adopt a learning approach, i.e. they have the necessary skills and, as other researchers suggest, present a significant capacity for positive psychological capital (Youssef-Morgan and Hardy 2014; Reichard et al. 2014; Dollwet and Reichard 2014).

Another theoretical contribution to understanding positive intercultural interactions is the seminal work of Stevens et al. (2008) on all-inclusive multiculturalism. This is an approach to multiculturalism that emphasizes diversity, which includes all employees, both minorities and non-minorities. It recognizes the role of differences and acknowledges them. Yet it also addresses non-minorities concerns about exclusion and disadvantage. According to Stevens et al., all-inclusive multiculturalism will develop positive relationships at work.

Stahl et al. (2010) also attempted to employ the POS lens to explore the outcomes of positive interactions in multicultural teams, such as creativity, satisfaction and communication effectiveness. With regard to creativity, they noted that intercultural contacts in teams may enhance the creative processes, preventing or delaying groupthink. Satisfaction is likely to occur in intercultural interactions, as noted earlier, since it satisfies a person’s need for variety and adventure. Additionally, it may result due to effective surmounting of cultural barriers. Finally, communication effectiveness is likely to improve if the surface-level cultural characteristics of teammates cease to act as a barrier, interpersonal trust ensues and individuals begin to focus on the deep-level aspects of cultural diversity.

Additionally, Youssef and Luthans (2012) proposed a developmental conceptual framework of positive global leadership as a vehicle that will help leaders “to turn their limited interactions with their followers into invigorating and elevating experiences” as well as “teachable moments and intentional, planned trigger events for development, growth, trust-building and intimacy” (p. 543). In other words, positive global leadership is a means to establish positive intercultural interactions at work. Youssef and Luthans portray positive global leadership as a systematic and integrated manifestation of leadership, over time and across cultures, which enhances the potential of people and organizations.

Rozkwitalska and Basinska (2015a) implemented the POS approach in an analysis of the impact of intercultural interactions on job satisfaction in MNCs and the inconsistent results concerning this in previous, rather limited number of studies. They constructed a model of the links between intercultural interactions and job satisfaction. It considers job satisfaction in a broader concept of work-related subjective well-being, which reflects the cognitive and affective components of job satisfaction, while the affective one is included in emotional balance. It also assumes that intercultural interactions further employees’ thriving, contributing to their subjective well-being. Moreover, the model highlights that various aspects of work in multicultural environments relate to job satisfaction and emotional balance in a different way, which may explain the inconclusive findings in prior studies.

Another example of the POS lens in research on intercultural interactions regards thriving in multicultural work settings of MNCs (Rozkwitalska and Basinska 2015b). In contrast to the studies mentioned above, this research reports the empirical findings from two MNCs. The authors infer that individuals who thrive in MNCs appraise their specific job demands as challenges. The multicultural work setting is highly demanding, yet MNCs enable their employees to cope with potential difficulties, which enhances their learning and triggers more positive than negative emotions. Furthermore, they note that the learning component of thriving is more significant than vitality.

3 Job Demands, Resources, Cognitive Appraisal and Intercultural Interactions’ Outcomes

3.1 Social Learning and Thriving in Intercultural Interactions

Adopting a learning approach in intercultural interactions keeps the promise of developing high-quality connections and relationships (Davidson and James 2009). Social learning theory, social cognitive theory (Bandura 2001) and thriving (Spreitzer et al. 2005) help to explain how intercultural interactions may foster learning.

According to social learning theory (Bandura 1977), behavior is learned from the environment as the process of observational learning takes place. Intercultural interactions confront individuals with exceptional learning opportunities, since people may mutually observe behaviors, values, beliefs and attitudes of the other person and consciously decide if they want to adopt them or not (learning occurs in both cases). Attention, as the antecedent sub-process of learning, can be even greater in a multicultural work setting, because it is attracted by behaviors that may be seen as novel, while motivation for learning can be additionally strengthened by MNCs, e.g. via job resources that facilitate interactions (Bakker et al. 2010).

The agentic perspective of social cognitive theory (Bandura 2001) allows for a more thorough explanation of learning in intercultural interactions. It states that personal agency functions within an extensive network of social interactions. Agentic transactions involve individuals as producers and products of social systems. Since intercultural interactions are more demanding than common interpersonal interactions, individuals are compelled to be active and learn, which makes them agents in such contacts. Additionally, job resources help people to be active and agentic, while accessibility of these resources enhance collective agency (Bandura 2000).

Being agents in intercultural interactions at work can be perceived via thriving. Thriving is congruent with flourishing, yet it is a somewhat narrower concept (Bono et al. 2013). Thriving reflects two conscious psychological states, namely a sense of vitality and learning (Spreitzer et al. 2005). Vitality refers to the positive experience of energy and aliveness and is seen as positive energy (Quinn 2009), whereas learning reflects that one acquires knowledge and skills and is able to use them, and it strengthens his/her sense of competence and efficacy. The concept assumes that work and the social context interplay, promoting positive employees’ functioning. Thriving is a self-adaptive process and it supports the growth of people (Paterson et al. 2014). It further posits that organizational learning only takes place in social interactions. Thus, intercultural interactions may show areas for necessary improvements and how to implement them (Carmeli et al. 2009), which is the essence of learning, and additionally invigorates vitality (Quinn 2009). Challenges that individuals face in intercultural interactions are a natural source of learning and development of their competency and generate various feelings and states. Moreover, thriving enhances not only individual outcomes such as job satisfaction, but it also contributes to organizational ones such as creativity and innovation (Rozkwitalska and Basinska 2015b).

3.2 Job Demands and Resources, Cognitive Appraisal and Intercultural Interactions

3.2.1 The Job Demands-Resources Model and Intercultural Interactions’ Outcomes

According to the Job Demands-Resources model (JD-R), although every job may have its own characteristics, the factors, which constitute them, can be grouped into job demands and job resources. Job demands reflect the various aspects of the job (i.e. the physical, psychological, social, or organizational ones) that involve sustained physical and/or psychological effort, resulting in certain physiological and/or psychological costs. Demanding intercultural interactions can be examples of such job demands. Additionally, employees in MNCs are confronted with cultural differences, multilingualism and a need to adjust (Rozkwitalska and Basinska 2015a), which can be seen as specific job demands in multicultural environments. JD-R assumes that job demands are not negative by their very nature, yet they may transform into job stressors.

Job resources, the second element in the model, refer to the various aspects of the job that are either helpful in achieving work goals or reduce job demands and the costs associated with them, and activate individual growth, learning and development (Bakker et al. 2010). With regard to MNCs, job resources that can leverage their challenging job demands are as follows: language training courses, ICT-enabled communication, special diversity initiatives, organizational culture, etc. Job resources play a motivational role because they are instrumental in achieving goals. JD-R posits that there are different combinations of job demands and job resources that affect employee well-being. However, the highest level of motivation can be attained in the combination of high job demands and high job resources, because resources are especially salient when job demands are challenging. Moreover, job demands are seen as predictors of job strain, whereas job resources may predict motivation, learning, commitment and job engagement (Bakker et al. 2010).

In the context of MNCs, job demands appear to be highly challenging. Thus, if they are combined with a sufficiently high level of job resources, intercultural interactions will likely produce many positive outcomes for both individuals and organizations.

3.3 Cognitive Appraisal and Intercultural Interactions’ Outcomes

The transactional theory of stress may provide additional elucidation of the “double-edged sword” results of intercultural interactions. Namely, it permits one to see working in multicultural environments of MNCs and handling intercultural interactions as a stressful situation, where the outcomes of the interactions that people can derive from them relate to their cognitive appraisal of the situation.

There are two kinds of cognitive appraisals when a person encounters a stressful situation, i.e. primary appraisal and secondary appraisal (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). The former occurs when the individual evaluates an event or situation (e.g. face-to-face communication with a manager from another country) as potentially hazardous to his/her well-being. The latter refers to the individual’s assessment of his/her ability to manage the event or situation (e.g. his/her level of proficiency in speaking a foreign language), which, in fact, is an estimation of the repertoire of the individual’s coping strategies that occurs with regard to, yet not necessarily after, a primary appraisal. The cognitive appraisal process is then the subjective interpretation of the situation and whether or not the individual perceives that s/he has the inner and/or outer resources to cope with it. Consequently, the outcomes possible for an individual and the very organization depend on the appraisal and the resulting coping resources implemented by the person to deal with the situation.

There are three kind of stress identified by Lazarus (1993), i.e. harm, threat and challenge. Each of them has different consequences for a person as well as his/her employing organization. Harm is an appraisal of the situation as a physical or emotional loss that has already been done. Threat means potential future harm, while challenge carries the potential for positive personal growth by applying coping resources to mitigate the stressful situation.

After the situation has been appraised by the individual, a behavior called coping follows that involves the decision about which behaviors to implement (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). A person may employ problem-focused coping (e.g. gathering necessary information, analyzing various options, conflict resolution, etc.) or emotion-focused coping, which involves positive reappraisal of the situation (e.g. an employee who felt offended in intercultural interactions may reinterpret the behavior of the other party as caused by his/her different cultural norms). Thus, the theory stresses that if a person evaluates a demanding situation, such as being involved in intercultural contacts, as a challenge rather than a threat and s/he employs an efficient coping strategy, the consequences can be positive.

4 Concluding Remarks

4.1 Conclusions

The overview of theoretical frameworks used in studies on intercultural interactions basically reveals how complex a phenomenon they are. Although there is ample literature that deals with the phenomenon, still researchers struggle to fully explain its genuine nature. The former contradictory findings call for additional explanations.

This chapter contributes to a better comprehension of the inconclusive results of intercultural interactions. Moreover, it embarks on positive cross-cultural scholarship research, since it provides a review of prior works on cultural differences that applied the POS lens and integrates the negative and positive views on intercultural interactions by referring to several psychological theories that are rather rarely employed in studies on the phenomenon.

This discourse shows that working in MNCs and dealing with intercultural interactions confront individuals with high job demands and that, due to cultural differences, they may hold negative expectations towards people from foreign cultures, which pose the risk of conflicts. However, how they handle the situation (i.e. job demands) depends on their cognitive appraisal. High job resources offered by MNCs as well as a positive evaluation of inner skills may help them to ascribe to the situation the meaning of challenge and to apply an appropriate coping strategy, be an agent and learn. Furthermore, such a motivating work environment can invigorate vitality, contribute to people’s thriving and other positive organizational outcomes, as a result of cross-social identities.

4.2 Contributions and Directions for Future Research

The analysis above may indicate what appears to be the missing element in earlier research and the resulting inconsistent findings. Namely, the previous studies have not treated working in MNCs and being involved in intercultural interactions as job demands and they have omitted the role of the appraisal of those job demands in shaping individual responses to them and their outcomes, such as e.g. thriving. Thus, the chapter supports the traditional perspective in the research as well as positive cross-cultural scholarship.

As the above discussion reveals, positive cross-cultural scholarship as a scientific inquiry is rather in an initial phase. Specifically, it requires more empirical studies that will show intercultural interactions to be explanatory mechanisms for various positive outcomes for both individuals and MNCs as well as what conditions that those relationships will be marked with vitality, mutuality and positive regard. Theoretical works still by far dominate the debate. Additionally, the application of the psychological theories mentioned above highlights the need to empirically explore the role of MNCs in determining the outcomes through a mediating factor of job resources. Therefore, future research may build on the theoretical underpinnings of the chapter.

References

Bakker A, van Veldhoven M, Xanthopoulou D (2010) Beyond the demand-control model: thriving on high job demands and resources. J Pers Psychol 9(1):3–16

Bandura A (1977) Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall, Oxford, England

Bandura A (2000) Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 9(3):75–78

Bandura A (2001) Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 52(1):1–26

Bono JE, Davies SE, Rasch RL (2013) Some traits associated with flourishing at work. In: Cameron KS, Spreitzer GM (eds) The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp 125–137

Brewer MB, Pierce KP (2005) Social identity complexity and outgroup tolerance. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 31(3):428–437, http://psp.sagepub.com/cgi/doi/10.1177/0146167204271710

Byrne D (1971) The attraction paradigm. Academic Press, New York, NY

Cameron KS, Spreitzer GM (2013) Introduction. What is positive about positive organizational scholarship? In: Cameron KS, Spreitzer GM (eds) The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp 1–14

Carmeli A, Brueller D, Dutton JE (2009) Learning behaviours in the workplace: the role of high-quality interpersonal relationships and psychological safety. Syst Res Behav Sci 98(November 2008):81–98

Carr SC et al (2001) Selecting expatriates in developing areas: “country-of-origin” effects in Tanzania? Int J Intercult Relat 25(4):441–457, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0147176701000153

Coates K, Carr SC (2005) Skilled immigrants and selection bias: a theory-based field study from New Zealand. Int J Intercult Relat 29(5):577–599, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0147176705000428. Accessed 23 May 2014

Cooper D, Doucet L, Pratt M (2007) Understanding “appropriateness” in multinational organizations. J Organ Behav 28(3):303–325, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/job.440/full

Davidson MN, James EH (2009) The engines of positive relationships across difference: conflict and learning. In: Dutton JE, Ragins BR (eds) Exploring positive relationships at work. Building a theoretical and research foundation. Psychology Press, New York, NY, pp 137–158

Dikova D, Sahib PR (2013) Is cultural distance a bane or a boon for cross-border acquisition performance? J World Bus 48(1):77–86, 10.1016/j.jwb.2012.06.009

Dollwet M, Reichard R (2014) Assessing cross-cultural skills: validation of a new measure of cross-cultural psychological capital. Int J Hum Resour Manage 25(12):1669–1696

Freeman S, Lindsay S (2012) The effect of ethnic diversity on expatriate managers in their host country. Int Bus Rev 21(2):253–268, 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2011.03.001

Harrison N (2012) Investigating the impact of personality and early life experiences on intercultural interaction in internationalised universities. Int J Intercult Relat 36(2):224–237, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0147176711000393. Accessed 7 June 2014

Hernández-Mogollon R et al (2010) The role of cultural barriers in the relationship between open-mindedness and organizational innovation. J Organ Chang Manage 23(4):360–376

Hinsz VB, Tindale RS, Vollrath DA (1997) The emerging conceptualization of groups as information processors. Psychol Bull 121(1):43–64, http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.43

Hogg MA, Terry DJ (2000) Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Acad Manage Rev 25(1):121–140, http://www.jstor.org/stable/259266?origin=crossref

Kahn WA (2009) Meaningful connections: positive relationships and attachments at work. In: Dutton J, Ragins BR (eds) Exploring positive relationships at work. Building a theoretical and research foundation. Psychology Press, New York, NY, pp 189–206

Klitmøller A, Schneider SC, Jonsen K (2015) Speaking of global virtual teams: language differences, social categorization and media choice. Pers Rev 44(2):270–285

Lauring J (2009) Managing cultural diversity and the process of knowledge sharing: a case from Denmark. Scand J Manage 25(4):385–394, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0956522109000955. Accessed 17 Sept 2014

Lauring J, Selmer J (2011) Multicultural organizations: common language, knowledge sharing and performance. Pers Rev 40(3):324–343, http://www.emeraldinsight.com/10.1108/00483481111118649. Accessed 3 Mar 2014

Lauring J, Selmer J (2012) Diversity attitudes and group knowledge processing in multicultural organizations. Eur Manage J 31(2):124–136, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0263237312000357. Accessed 22 Feb 2014

Lazarus RS (1993) From psychological stress to the emotions: a history of changing outlooks. Annu Rev Psychol 44(1):1–22

Lazarus R, Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer, New York, NY

Leong C-H, Liu JH (2013) Whither multiculturalism? Global identities at a cross-roads. Int J Intercult Relat 37(6):657–662, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0147176713001065. Accessed 16 Sept 2014

Li J, Xin K, Pillutla M (2002) Multi-cultural leadership teams and organizational identification in international joint ventures. Int J Hum Resour Manage 13(2):320–337, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09585190110103043. Accessed 29 Apr 2014

Lin X, Malhotra S (2012) To adapt or not adapt: the moderating effect of perceived similarity in cross-cultural business partnerships. Int J Intercult Relat 36(1):118–129, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0147176711000137. Accessed 18 Dec 2014

Liu LA et al (2012) The dynamics of consensus building in intracultural and intercultural negotiations. Adm Sci Q 57(2):269–304, http://asq.sagepub.com/lookup/doi/10.1177/0001839212453456. Accessed 25 May 2014

Loh J, Min I, Restubog SLD, Gallois C (2009) The nature of workplace boundaries between Australians and Singaporeans in multinational organizations: a qualitative inquiry. Int J Cross Cult Manage 16(4):367–385, http://www.emeraldinsight.com/10.1108/13527600911000348. Accessed 2 July 2014

Luijters K, van der Zee KI, Otten S (2008) Cultural diversity in organizations: enhancing identification by valuing differences. Int J Intercult Relat 32(2):154–163, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0147176707000740. Accessed 18 Mar 2014

Luo Y, Shenkar O (2006) The multinational corporation as a multilingual community: language and organization in a global context. J Int Bus Stud 37(3):321–339, http://www.palgrave-journals.com/doifinder/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400197. Accessed 29 Apr 2014

Magier-Łakomy E, Rozkwitalska M (2013) Country-of-origin effect on manager’s competence evaluations. J Intercult Manage 5(4):5–21, http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/joim.2013.5.issue-4/joim-2013-0023/joim-2013-0023.xml

Mamman A, Kamoche K, Bakuwa R (2012) Diversity, organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior: an organizing framework. Hum Resour Manage Rev 22(4):285–302, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S105348221100074X. Accessed 20 Feb 2014

Mannix E, Neale MA (2005) What differences make a difference? The promise and reality of diverse teams in organizations. Psychol Sci Public Interest 6(2):31–55

Molinsky A (2007) Cross-cultural code-switching: the psychological challenges of adapting behavior in foreign cultural interactions. Acad Manage Rev 32(2):622–640, 10.5465/AMR.2007.24351878

Paterson TA, Luthans F, Jeung W (2014) Thriving at work: impact of psychological capital and supervisor support. J Organ Behav 35(3):434–446

Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR (2008) How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. Eur J Soc Psychol 38(6):922–934, http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ejsp.504

Przytuła S et al (2014) Cross-cultural interactions between expatriates and local managers in the light of Positive Organizational Behaviour. Soc Sci (Socialiniai mokslai) 4(4):14–24

Quinn RW (2009) Energizing others in work connections. In: Dutton J, Ragins BR (eds) Exploring positive relationships at work. Building a theoretical and research foundation. Psychology Press, New York, NY, pp 73–90

Reichard RJ, Dollwet M, Louw-Potgieter J (2014) Development of cross-cultural psychological capital and Its relationship with cultural intelligence and ethnocentrism. J Leadersh Org Stud 21(22):154–164

Roberge M-É, van Dick R (2010) Recognizing the benefits of diversity: when and how does diversity increase group performance? Hum Resour Manage Rev 20(4):295–308, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1053482209000795. Accessed 28 Jan 2014

Rozkwitalska M (2012) Human Resource Management strategies for overcoming the barriers in cross- border acquisitions of multinational companies: the case of multinational subsidiaries in Poland. Soc Sci (Socialiniai mokslai) 3(3):77–87

Rozkwitalska M, Basinska BA (2015a) Job satisfaction in the multicultural environment of multinational corporations. Balt J Manage 10(3):366–387. http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/10.1108/BJM-06-2014-0106

Rozkwitalska M, Basinska BA (2015b) Thriving in multicultural work settings. In Vrontis D, Weber Y, Tsoukatos E (eds) Conference readings book proceedings. Innovation, entrepreneurship and sustainable value chain in a dynamic environment. September 16–18, 2015, EuroMed Press, Verona, pp 1437–1450. http://emrbi.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/euromed2015 book of proceedings-2015-09-08.pdf

Rozkwitalska M, Chmielecki M, Przytuła S (2014) The positives of cross-cultural interactions in MNCs. Actual Problems Economics 57(7):382–392

Sano M, Martino LAD (2003) “Japanization” of the employment relationship: three cases in Argentina. CEPAL Rev 80:177–186

Shore LM et al (2009) Diversity in organizations: where are we now and where are we going? Hum Resour Manage Rev 19(2):117–133, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1053482208000855. Accessed 30 Jan 2014

Snyder CR, Fromkin HL (1980) Uniqueness: the human pursuit of difference. Springer, New York, NY, https://books.google.com/books?id=6819BwAAQBAJ&pgis=1

Spreitzer G et al (2005) A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organ Sci 16(5):537–549, http://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/orsc.1050.0153. Accessed 2 Sept 2014

Stahl GK, Tung RL (2014) Towards a more balanced treatment of culture in international business studies: the need for positive cross-cultural scholarship. J Int Bus Stud, 1–24. http://www.palgrave-journals.com/doifinder/10.1057/jibs.2014.68

Stahl GK et al (2009) Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: a meta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups. J Int Bus Stud 41(4):690–709, http://www.palgrave-journals.com/doifinder/10.1057/jibs.2009.85. Accessed 28 Apr 2014

Stahl GK et al (2010) A look at the bright side of multicultural team diversity. Scand J Manage 26(4):439–447, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0956522110001028. Accessed 28 Apr 2014

Stevens FG, Plaut VC, Sanchez-Burks J (2008) Unlocking the benefits of diversity: all-inclusive multiculturalism and positive organizational change. J Appl Behav Sci 44(1):116–133

Tajfel H, Turner JC (1986) The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG (eds) The social psychology of intergroup relations. Nelson-Hall, Chicago, IL, pp 7–24, http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2004-13697-016

Thomas DC, Fitzsimmons SR (2008) Cross-cultural skills and abilities. From communication competence to cultural intelligence. In: Smith PB, Peterson MF, Thomas DC (eds) The handbook of cross cultural management research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp 201–218

van Veen K, Marsman I (2008) How international are executive boards of European MNCs? Nationality diversity in 15 European countries. Eur Manag J 26:188–198

van Veen K, Sahib PR, Aangeenbrug E (2014) Where do international board members come from? Country-level antecedents of international board member selection in European boards. Int Bus Rev 23(2):407–417, 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.06.008

Wayne B, Dutton JE (2009) Enabling positive social capital in organizations. In: Dutton JE, Ragins BR (eds) Exploring positive relationships at work. Building a theoretical and research foundation. Psychology Press, New York, NY, pp 325–345

Youssef CM, Luthans F (2012) Positive global leadership. J World Bus 47(4):539–547, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1090951612000089. Accessed 22 Jan 2014

Youssef-Morgan CM, Hardy J (2014) A positive approach to multiculturalism and diversity management in the workplace. In: Teramoto Pedrotti J, Edwards L (eds) Perspectives on the intersection of multiculturalism and positive psychology. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 219–233

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the financial support from National Science Centre in Poland (the research grant no. DEC-2013/09/B/HS4/00498).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rozkwitalska, M. (2017). Intercultural Interactions in Traditional and Positive Perspectives. In: Rozkwitalska, M., Sułkowski, Ł., Magala, S. (eds) Intercultural Interactions in the Multicultural Workplace. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39771-9_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39771-9_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-39770-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-39771-9

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)