Abstract

The main aim of this chapter is to introduce readers to the idea of social capital. Then relationships between social capital and trust are analyzed. Finally, both these ideas are placed in the context of multicultural organizations.

The term ‘social capital’ appeared in the 1960s. Social capital is identified as symbolic common goods of a society, which foster the development of social trust and norms of reciprocity, which in turn leads to more effective forms of organization. Social capital is an aggregate of variables determining the nature of secondary relationships. It can also be seen as a skill of interpersonal cooperation within groups and organizations in order to realize common interests.

Interpersonal trust is an important factor determining relationships, both in the family and in the organization. Interpersonal trust is a reflection of a resource of experience and observation of a person, which would allow him or her to predict that confidence in the given person meets expectations.

The chapter draws clear boundaries between trust and social capital, at the same time explaining and exploring implications of these two perspectives on the issue of organizational management in a multicultural context.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

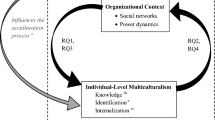

An immanent feature of all groups of people is the establishment of social ties between their members. These ties are based on trust, which is located at a number of levels, can take different forms, and may be of varying levels of intensity, but it is a universal element of interpersonal relationships. When we carry out research into multicultural organizations, we face the issue of understanding how trust relationships are established between people in them. This means referring to a basic concept of the social sciences—“social capital”.

Thus, we can ask whether multicultural organizations have any distinguishing features in the area of social capital and trust relationships between people. If the answer is positive, then we can ask about the characteristics of the relationships between social capital and trust in multicultural organizations. In fact, this is a question about the unique characteristics of social capital in multicultural organizations, which is the subject of this chapter.

The main aim is to introduce readers to the idea of social capital. It will then analyze the relationships between social capital and trust, indicating the theoretical and empirical closeness of the meaning of these terms. Next, selected limitations to the development of social capital will be presented, mostly from the perspective of Poland. And finally, both ideas will be placed in the context of multicultural organizations.

The chapter describes certain fluid boundaries between trust and social capital, at the same time explaining and exploring implications of these two perspectives on the issue of organizational management in a multicultural context.

2 Social Capital and Its Components

The notion of social capital is not a novelty in the discourse of the social sciences and humanities. The term was first used by Hanifan (1916) in reference to research into rural centers. Over the last decades, issues concerning social capital were mostly studied by political scientists and sociologists. In works by such researchers asBourdieu (1986), Coleman (1988) and Putnam (1993, 2000), social capital as a construct became a complex representation of human values and interpersonal relationships. The notion was treated as a constructive element of economic prosperity (Fukuyama 1997), regional development (Grootaert and Bastelaer 2002), collective action (Burt 1992) and democratic governance (Putnam 1993, 2000). A number of concepts of social capital have been created to date, and it has to be said that the notion has been most popular among sociologists.

The term “social capital” was popularized in the social sciences and humanities in the 1960s. Social capital is considered equivalent to the symbolic common good of the society, which supports the development of social trust and norms of reciprocity, and in consequence leads to more effective forms of organization. The concepts of social capital can be found in a number of works by such authors as Jacobs, Coleman, Fukuyama and Putman. According to Jacobs (1961), social capital is a set of variables determining the character of secondary relationships. Coleman (1988) describes social capital as the human ability to cooperate within groups and organizations in order to further the common interest.

The notion of social capital achieved worldwide popularity thanks to a popular book by Putnam (2000) Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. The author believes that, despite the fact that Americans became wealthier, their sense of community started to disintegrate. Cities and the suburbs became edge cities and exurbs—vast and anonymous places where human activity is limited to working and sleeping. As people spent more time working, commuting, and watching TV, they had less time for meeting their local communities, establishing civic organizations, or even meeting their friends and family.

An increase in the popularity of the notion of social capital is also connected with its common use in a number of disciplines. Fukuyama defined and studied social capital on the basis of analyses in political science and sociology, looking for the sources of stability and social prosperity (Fukuyama 1997). Sociologists and educationalists associate the issue of social capital with inequality, morality, openness, inclusiveness, education, social welfare, resocialization, and a number of different social phenomena (Kawachi et al. 1997; Morrow 1999; Dasgupta and Serageldin 2001). In Poland, the issue of social capital is addressed by numerous sociologists, political scientists, cultural anthropologists, and over the last decades also by economists and management specialists (Herbst 2007; Trutkowski and Mandes 2005; Sztaudynger and Sztaudynger 2005; Theiss 2012; Czapiński 2008; Kostro 2005; Zarycki 2004; Sułkowski 2001).

Two of the greatest difficulties related to using the phenomenon of social capital are the high ambiguity of the term and lack of credible methods for measuring it. Since virtually the moment the term “social capital” was coined, it referred to certain elusive characteristics concerning relationships between individuals. We can quote here the author of the concept, Hanifan: “I do not refer to real estate, or to personal property or to cold cash, but rather to that in life which tends to make these tangible substances count for most in the daily lives of people, namely goodwill, fellowship, mutual sympathy and social intercourse” (Hanifan 1916, p. 130).

The same recurring ideas can be found if we have a look at the most important definitions from the 1970s (Loury 1977), the 1980s (Bourdieu 1986; Coleman 1988), the 1990s (Burt 1997; Fukuyama 1999, 2001; Knack and Keefer 1997; Putnam et al. 1993), and the last decade (Woolcock and Narayan 2000; Dasgupta 2000; Lesser 2000; Fafchamps 2006; Sen 2003). For example, according to Fukuyama “social capital can be defined simply as the existence of a certain set of informal values or norms shared among members of a group that permit cooperation among them” (Fukuyama 2001, p. 169).

Understanding social capital as a kind of “rooting” (Granovetter 1985) is probably the most popular understanding of “social capital”. From this perspective, we acknowledge that it is impossible to understand the behavior of economic units without proper examination of the social structure they are rooted in. A model in this case can be the definition proposed by Bourdieu, who understands this term as actual or potential resources which are linked within a network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition, or in other words, membership in social groups (Bourdieu 1986). If we have a look at the aspects indicated as the primary ones, we will not find any systematic approach that would explain what falls into the semantic scope of “social capital”, and what does not.

Sometimes, social capital is also defined from the angle of so-called cultural capital or relational capital. Understood like this, capital refers to resources that social elites have at their disposal. Generally, four types of capital can be distinguished: political, material, cultural, and social. Material capital, which includes all financial and material resources owned by household members, is an object of inheritance. Such inherited material capital often determines the fate of children. Cultural capital is a set of competencies, skills, and knowledge acquired by an individual, which is a prerequisite to the gaining of a certain position within the social structure (Wnuk-Lipiński 1996). The cultural capital of parents is transmitted to children as part of the socialization process. Thanks to the process of socialization, education, and upbringing children can acquire this set of key social competencies. Cultural capital is transmitted and assimilated both unconsciously and consciously. Studies conducted by Bernstein indicate that children learning a specific language acquire it as an “elaborated code” or a “restricted code”, which has a significant influence on their future ability to understand and interpret reality (Bernstein 1990). Parents try to consciously direct the child’s intellectual development, assuming that it is necessary to shape certain skills which will be useful for the child’s future professional career. According to Bourdieu, there is semantic parallelism between a social hierarchy arising from economic conditions and a hierarchy of approved cultural content (Bourdieu 1990). Giddens indicates two ways of transforming structural properties entangled in the reproduction of modern industrial capitalism, which are tightly linked to the reproduction of elites (Giddens 2003): private property—money—capital—labor contract—profit; private property—money—educational advantage—occupational position.

Understood like this, economic (material) capital is a determinant of cultural capital. Values and norms instilled within the socialization process form a kind of “symbolic compulsion” (“symbolic violence”), which structuralizes and rationalizes the existing social order. Naturally, this order supports those in power and social elites who have material capital (Bourdieu 1990). Social capital was defined by Edmund Wnuk-Lipiński as “all informal social relationships (colloquially called “contacts”), thanks to which individuals increase the probability of joining the elites or maintaining their position in the elites” (Wnuk-Lipiński 1996, p. 151).

In fact, one could even attempt to divide these ways of understanding social capital into several categories. The first group of definitions associates social capital with a network structure. This perspective highlights the significance of a social structure within which individuals operate. In order to understand the functioning and the effectiveness of the whole network and to derive potential benefits from it, attention is directed to the characteristics of the given network and the position of individuals in its context (Burt 2000; Sciarrone 2002; Sabatini 2006; Lin 2008). The second group of definitions emphasizes a distinctive feature of social ties, i.e. the trust factor. In this case, there is an unspoken assumption that not all networks or relationships are good building blocks of social capital—only the ones with a relatively high level of trust are suitable (Bjørnskov 2003; Beard 2007; Cassar et al. 2007). And finally, the third group of definitions combines the first two proposals into a concept referring to the network aspect and the norms of social trust. Its aim is to capture qualities related to forming groups, social participation, or the level of group solidarity (Knack and Keefer 1997; Narayan and Lant 1999; Putnam 2001; Miguel et al. 2006; Woolcock and Narayan 2000). The last two approaches offer an analysis at the level of the whole community, even if its elements refer directly to the specific features of individuals.

3 Elements of Social Capital

The concept of social capital, despite there being different definitions, attracts supporters among scholars from many disciplines. Interpersonal relationships and “relational capital” form a large part of these definitions. For the purpose of further discussion, I will define social capital as relationships between individuals and organizations that facilitate operation and create value (Adler and Kwon 2000; Seifert et al. 2003).

As an attribute of a society, social capital can be understood as a specific characteristic of an environment that makes it easier for people to cooperate. In this case, the question of solutions that can be provided by communities in relation to the issue of a superior or common good is of key importance (Durlauf 2005). Social capital makes it possible to reduce the cost of transactions connected with uncertainty or information deficiency. Thus, it can be said that it provides “soft”, non-economic solutions to economic problems (Knack and Keefer 1997; Kawachi et al. 1999).

Matysiak believes that social capital, which is based on the institutional and cultural achievements of a society, provides benefits to all participants in the social distribution of work (Matysiak 1999). Social capital translates into the level of social trust supporting the creation of intentional social groups. A high level of social trust, and so of social capital, means that secondary social groups form relatively easily in a society. Fukuyama believes that a high level of social trust favors the creation of large organizations which go beyond the stage of small enterprises, while a low level of trust limits the possibilities of economic consolidation, favoring the development of the sector of small and medium enterprises and family companies. In the context of the internationalized, and particularly the global economy, larger organizations are often more effective in many sectors than smaller enterprises. Thus, countries where business organizations consolidate more quickly and more easily will offer conditions for the development of more competitive economies and organizations.

Social capital, in its broadest sense, refers to the internal (cultural and social) coherence of a given group, trust, norms, and values controlling interactions between people, networks, or institutions (Parts 2003). Social trust and norms are necessary conditions for the existence of a process; however, it cannot be viewed only from their perspective. Social capital only provides for the possibility of trust arising, but does not guarantee this (Ahn and Ostrom 2008; Dasgupta 2000). Moreover, the use of such terms as “trust” and “social norms” blurs the boundaries between different levels of social interactions. The developing network of social relationships includes norms, values, and obligations, offering people related to it the possibility of development (Haley and Haley 1999; Yli-Renko et al. 2001). For example, if we treat social capital as common trust (Bjørnskov 2003), we make an unspoken assumption that the accumulation of social capital through building relationships with people within unrelated groups will improve the general trust level. And if we think about the creation of social norms and their role in the shaping of a sense of common purpose (Putnam et al. 1993), we ignore the fact that society can include completely different norms and different groups can make use of them (Warren 2008).

In the literature there is general agreement on the elements of social capital—its components are more or less interrelated. Elements of social interaction can be divided into two categories: structural elements, which facilitate interaction, and cognitive elements, which build aptitude for actions that are advantageous to the group. Structural elements also include social or civic participation, while cognitive elements cover all forms of trust and norms. Although most researchers agree about the significance of cognitive and structural aspects within social capital, it can be assumed that both sides of the coin support each other. For example, informal communication teaches cooperation with strangers in order to achieve a common goal, while norms are essential in order to avoid opportunism (Parts 2003).

Another potential result of involvement in different networks is personal interaction, which generates relatively cheap and reliable information about the solidity of other people, reducing the risk related to trusting someone. On the other hand, previously existing, common and diffused trust indicates a readiness to establish cooperation with strangers. Regarding relationships of this type, one can briefly say that social interaction requires communication skills and trust, which improve in the course of cooperation with people. Thus, different dimensions of social capital should be treated as complementary and related to the same overall concept (Parts 2003).

Indicators of social capital can be divided into two groups, psychological and socio-economic characteristics such as income, education, family, social status, values held, personal experiences—all these elements determine the willingness of individuals to invest in social capital. Contextual and systemic factors at the level of a community or a nation include, for example, the general level of development, the quality of operations of formal institutions, distribution of resources, social polarization, and previously existing mental schemas of trust and cooperation. Current research concentrates on the indicators of the individual level, studied empirically by such researchers as Alesina and Ferrara (2000), Christoforou (2005), Halman and Luijkx (2006), Kaasa and Parts (2008), and others. Despite the fact that the results of empirical studies do not always agree, one can make certain generalizations through references to indicators of different types of social capital.

4 Social Capital in Economics and Management

The notion of social capital entered the discourse of management science thanks to its proximity to economy, organizational sciences, and managerial practices (Cohen and Prusak 2001). For example, Kostro (2005) claims that social capital determines the actual resources, the existence of which is of social significance. Kostro listed the following characteristics of social capital (Kostro 2005; Sierocińska 2011):

-

1.

Production—social capital is created with the use of specific material resources, financial resources, work, and time.

-

2.

Transformation—social capital has the ability to transform certain goods (material resources, financial resources, work, and time) into benefits that cannot be obtained in a different way (e.g. the use of someone else’s knowledge, skills, ensuring privileged treatment, receiving emotional support or support in a difficult situation etc.).

-

3.

Investment process—material resources, financial resources, work, and time are invested in the creation of an atmosphere favoring mutual trust. Stronger ties require larger investments, while weaker ties require smaller investments.

-

4.

Diversity—similarly to material capital, social capital is heterogeneous.

-

5.

Different degrees of stability—duration of relationships depends on their type.

-

6.

Attention to social capital—in order for social capital to maintain its productivity, it needs to be “used” from time to time.

-

7.

Predictability—when one knows the type of relationships (the degree of stability of social capital), one can predict certain situations.

-

8.

Alternative cost—the creation and maintenance of social capital are preceded by the calculation of costs and benefits.

-

9.

Transferability—this characteristic of social capital is present only partially, as it is impossible to resell or hire social capital. Social capital can be transferred or inherited in a certain way (e.g. parents’ friends become also children’s friends).

In academic circles, the already mentioned proximity to the economy and organizational sciences satisfied the need for a theoretical mechanism explaining many issues, which can be applied to subjects developed within the same intellectual movement (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). This was mostly related to the development of a cultural discourse or in fact the issue of the integration of culture, also called the issue of strong organizational cultures (Sułkowski 2012; Sikorski 2008). Values and norms form the basis for interpersonal interactions that are supposed to be the bond of all organizational systems. Also a group of problems related to the concept of organizational identity and identification with the organization was related to this intellectual formation (Whetten 2006). Other concepts mentioned include corporate social responsibility, the way enterprises interact with their environment; the beneficiary model, according to which “property” is something more than economically understood capital; knowledge management. Consideration for the way an enterprise can organize its internal communication separately from its social context (Jones et al. 2001).

5 Trust, Social Integration and Cultural Differences

One of the most discussed elements of social capital is trust. The notion of “trust” is quite commonly used in the social sciences, which is why there are a large number of definitions. Grudzewski et al. (2007) list over 30 definitions in six areas of study: psychology and sociology, management, marketing, organizational behavior, public relations, and information systems.

According to Ratajczak, interpersonal trust is a significant factor determining interpersonal relationships, both in families and organizations (Ratajczak 1983). Deutsche believes that interpersonal trust is a reflection of a certain set of experiences and observations of people, allowing them to predict whether the person they trust will measure up to their expectations (Deutsche 1973). According to Zand, the notion of trust includes (Zand 1972):

-

one’s own intention to trust someone,

-

actual behavior compatible or incompatible with this intention,

-

expectations of others in relation to the fact that they are worthy of trust,

-

the fact that people perceive their behavior as trustworthy,

-

situational context,

-

hypothetical consequences of a low or high level of trust.

In the analysis conducted, intercultural interactions were associated with social capital and interpersonal trust, and evidence of a positive correlation between them was shown.

Generally, trust is based on certain values shared by people, and its development depends to a large extent on the process of primary and secondary socialization at a young age. This means that trust is a stable characteristic, independent of the context, actions of the other person, or previous experiences (Uslaner 2002). This kind of trust is also referred to as “moral trust”. A similar term is “common trust” or “social trust”, which is also connected with the hypothetical trust towards community members. It is inclusive to a similar degree as moral trust, however, there are two aspects that make it different: it depends on the context and it is prone to modeling through individual or group experience (Levi 1996). Common trust indicates the potential readiness of citizens for cooperation and hypothetical readiness for common civic participation (Rothstein and Stolle 2002). At the level of the whole society, common trust is based on certain ethical habits and moral norms concerning reciprocal actions (Fukuyama 2001). Most researchers agree that trust requires a number of elements: considerable personal vulnerability of the person placing trust in someone, uncertainty about the future actions of individuals in whom trust is placed, and a specific object or problem entrusted to the person in whom trust is placed, or a confidant, which may include children, health, or money (Hall et al. 2001). Trust can be considered from different perspectives, depending on the way it is experienced and expressed, the object of trust, and attributes or characteristic features that lead to the development of trust.

Social capital is closely related to economic prosperity, regional development, collective action, and democratic governance (Fukuyama 1997). However, it cannot explain all these social phenomena in and of itself. Thus, one should not ignore the issue of trust when writing about social capital.

There are many contradictory opinions concerning this issue. Is trust a condition for the development of social capital or its effect? Placing these notions in the organizational context is significant for a number of reasons. When searching for the implications of both views on the issue of organizational effectiveness, one should remember not only about relationships but also about maintaining the fundamental division within an analysis into trust and social capital. The literature is dominated by a view of an individual (Baker 2000), a nation (Putnam 1993), and a culture or religion (Fukuyama 1997), rather than an organization. Analysts often perceive organizations as machines producing goods, services, or knowledge, and as enterprises managing resources and coordinating the work of individuals in order to carry out the actions planned. Many of them point to organizations with high social capital, which have not had reflections about the significance of this notion for a long time. This means that organizations often ignore social capital and hardly ever understand or analyze it, or discuss the social networks behind it. Yet, the economic, social, or technological worlds they populate require them to understand this concept far more deeply than ever before (Cohen and Prusak 2001).

Common trust is often juxtaposed with special or institutional trust. These kinds of trust are called “horizontal” and “vertical” respectively. Institutional trust refers to the feelings one has for the social system (Luhmann 1988) and public institutions and their officers (Hardin 1992). Rothstein and Stolle (2003) developed an institutional theory of generalized trust, according to which every citizen distinguishes institutions based on at least two aspects: they expect them to be represented by certain persons related to politics, law, or social institutions, and they expect them to take a neutral, impartial approach. In general, trust towards institutions determines the way citizens experience the sense of security and protection, the way citizens transmit information between public institutions and other citizens, the way citizens watch the behavior of their fellow citizens, and the way they feel discrimination against themselves or their family and friends (Rothstein and Stolle 2002).

6 Limitations to the Development of Social Capital

The literature offers a number of examples of limitations to the development of social capital (Łopaciuk-Gonczaryk 2008; Czapiński 2011). The most important reasons for the weakness of social capital include:

-

1.

Generalized lack of social trust (Batorski 2013).

-

2.

Weakness of civil society (Golinowska and Boni 2006).

-

3.

A low level of openness and inclusiveness in the society (Theiss 2011).

-

4.

The “social void” phenomenon described on the basis of the example of Poland by Nowak (1979).

-

5.

The “amoral familism” syndrome identified in the research conducted by Banfield (Reis 1998; Banfield 1967).

The last case of the reduction of social capital will be discussed as an example, as this is a phenomenon studied in Poland (Sułkowski 2004; Dzwończyk 2005).

Nowak believed that Poland during partitions, and then under the control of the Soviet Union was a country completely lacking civic institutions, within the culture of which a collective defense mechanism developed in the form of lack of trust towards the oppressive state and its departments, and relying only on family, neighborhood, and church communities. Commercial and public organizations also occupied this “social void”, becoming old-boy networks in opposition to the authorities. However, the strengthening of family and neighborhood ties, in combination with the weakness of civil society, leads to a reduction in social capital.

Banfield emphasizes the negative effects of overly strong family ties compared to social ties, using the term “amoral familism” in his analysis of southern Italy. Studying the functioning of traditional peasant families in Montenegrano, Banfield (1953, 1979) pointed to the conservative and anti-modernist influence of strong family ties, which delay economic development. The norms of “amoral familism” come down to the maximization of material benefits of a family at the expense of everyone from outside the family. “Amoral familists” cultivate high-quality social contacts and follow moral rules at a family level, however, they often treat people from outside the family distrustfully and cynically, striving for profits only. Miller (1974) describes familists as people who strive for the prosperity of their family at the expense of non-family social ties. Silverman (1970) notes that Banfield’s analysis is unique to rural communities in the south of Italy, where familism manifests itself in the domination of families within the social structure, the lack of complex, institutionalized social relationships between a family and the broader community, the lack of community leaders, and weak social ties. Putman (1993) combined a thesis about the existence of “amoral familism” with a thesis about the reduction of social capital. Using the example of southern Italy, he observed that familism makes it difficult to establish broader social ties, reinforcing clientelism and corruption in politics as well as conservative tendencies. Putman’s diagnosis was criticized. According to Piselli (2001), Putman adopted an ethnocentric American perspective of civil society to assess rural communities in the south of Italy. Above all, he failed to see that family ties did not concentrate on a nuclear family but on an extended family and, probably most importantly, he did not take into consideration the extensive and complex ties of loyalty and relationships covering groups of neighbors and friends (e.g. between fellow soldiers). Therefore, these non-family social ties were strong, even if they were completely different from the ties present in the industrialized American society. LaBarbera (2001) adds distrust of local politicians and political life to factors fostering “amoral familism”.

Banfield’s thesis about “amoral familism” is disputable. The question arises whether family ties must lead to the weakening of broader social ties. The family crisis related to the growth of individualism entails the weakening of family ties and disintegration of other social ties. The strength of family ties in a traditional agricultural community can be positively correlated with the strength of ties with neighbors. As Miller (1974) notes, Banfield could have overestimated the significance of the cultural factor leading to “amoral familism”, as care of the family needs could have been simply related to the difficult living conditions of the community in question. At that time, the need to maintain one’s family was elementary, pushing other social ties into the background. Transferring the theses of Banfield from small pre-industrial rural communities directly to the post-industrial mass society should be viewed skeptically. Theses about the harmful effect of the increasing strength of family ties on social capital cannot be accepted based on speculation, but on research only.

I think that correlations between family ties and other social ties are complex because they are exposed to the influence of a number of different variables. The cultural background imposes criteria for the assessment of the value of families and other social groups, and establishes normative rules for their coexistence. Economic factors can support the establishment or limitation of cooperation in social groups extending beyond families. Institutional and legal variables can reinforce or weaken family ties in comparison with other social ties. This is why the familism syndrome needs to be examined in each society separately. A high level of familism does not have to entail a reduction in other social ties (Sułkowski 2003).

However, it is worth considering whether the factors constituting “amoral familism” are now present in the Polish society. Does Poland face:

-

Lack of trusted local social leaders?

-

General weakness of social ties?

-

Growing distrust of political institutions and politicians?

-

Increased significance of a family at the expense of other social groups?

-

Lack of social and civil structures ranking between a family and the state?

If we assume that these factors are present, then do they contribute to the development of the “amoral familism” syndrome in Poland (Sułkowski 2013)? Studies and analyses described in this work are mostly aimed at the exploration of the specificity and effects of Polish familism, particularly in relation to organizations and the whole economy.

7 Social Capital in a Multicultural Working Environment

Social capital is considered to be one of the main factors increasing economic effectiveness by enhancing cooperation and reducing transaction costs at the level of countries, regions, or multinational enterprises. It has been proven that regions and countries with large social capital achieve a higher level of innovativeness and growth than societies with low indicators of trust and active citizenship (e.g. Knack and Keefer 1997; Rose 1999; Ostrom 2001). Speaking more generally, social capital is perceived as the main factor determining social networks of people and enterprises. It offers a broad scope of benefits at the level of individuals, organizations, and the whole society.

Ethnically diverse workplaces are interesting locations to study interpersonal relationships and their potential to create social capital along and across ethnic groups. Workplaces reflect social spaces closed to a different extent, where interactions between workers are rather continuous, depending on the tasks performed. Thus, these spaces represent ties, as part of which workers can build up social capital including their colleagues of a different ethnic or social background.

Social capital has become a significant resource for multinational enterprises, as in order to maintain their competitiveness on the global market they need adequate resources: information technology, knowledge, access to distribution networks etc. This is why multinational enterprises need to have the ability to derive benefits from their social capital.

With an adequate level of social capital, it is possible to effectively manage knowledge through ties between network participants (Zhou et al. 2007). Tacit knowledge is particularly valuable from the technical and commercial points of view, mostly due to the fact that it is impossible to replicate and difficult to transfer. Social capital offers access to the deposits of this knowledge, so it has a positive effect on its use and development (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). Each enterprise can increase its knowledge resources not only through its own operations but also through the operations of its network partners and entities from its partners’ networks (Johanson and Vahlne 2009).

Social capital is significant for multinational enterprises. The ones operating on global markets hardly ever have all the resources that enable them to be effective, which is why they obtain necessary resources through formal and informal relationships with other enterprises.

Access to information, generated as a result of good relationships within a network, reduces the cost of obtaining information (Zhou et al. 2007). Moreover, such information is usually of higher quality and it is more significant and more valid than information from other sources (Adler and Kwon 2000, p. 29). Zhou et al. (2007) identified three sources of benefits resulting from access to information in a network as part of the internationalization process:

-

1.

access to the knowledge of market opportunities in other countries;

-

2.

the possibility of making use of advice and knowledge gained through the (empirical) experience of other network participants (experiential knowledge);

-

3.

the possibility of receiving recommendations and support from third parties (Zhou et al. 2007, as cited in: Doryń 2010).

It is worth emphasizing that the cultures of Asian countries focus on social relationships to a greater extent than Western cultures. Thus, relational capital based on guanxi (China), kankei (Japan), or inmak (Korea) creates business activity patterns in a number of countries in Asia. As a consequence, the social capital of Asian enterprises provides them with a potential advantage on the global market. Western enterprises need to develop social capital and learn how to manage networks of relationships in order to achieve similar results. They can learn this from Asian enterprises (Hitt and Lee 2002).

Unfortunately, social capital functioning at the level of organizations has its limitations. Business entities become dependent on their social networks, and so they encounter alternative costs and limitations resulting from the direction of development taken in the past. Moreover, while Asian enterprises have strong network relationships in their home markets, on the global market they have to establish far more links in order to operate effectively. As a consequence, development and management of social capital have become significant challenges to the maintenance of worldwide competitiveness (Hitt and Lee 2002).

Enterprises function in a competitive environment, fighting for markets against complex networks of companies—these networks contrast with the position of individual competitors (Hitt et al. 1998). Companies operating within networks have many more resources allowing them to increase their competitiveness. They would not be able to do this on their own. In order to improve their competitiveness, most enterprises need additional resources, and this is why they seek to form their own networks.

A corporation interacts with a given community at a number of levels. Thus, research requires an approach acknowledging the scale of its operations and its attempts to function in local contexts in order to build up social capital. It is important to emphasize the influence of social capital on the macro, mezzo, and micro levels. Studying social capital as part of existing economic theories about the functioning of organizations leads to the conclusion that it can be understood as their lowest common denominator. In the area of academic economy, the issue of relationships reappears in a number of forms, making the question of social capital an important element of organizational theory. Treating this significant notion like this allows us to define it as a factor of evolutionary change within economic organizational theory. The evolution of organizational theory clearly indicates that the newer the concept, the greater emphasis is placed on social capital and the easier it is to understand, while the latest theories offer an in-depth understanding of these really important issues.

8 Conclusions

As studies suggest, multicultural organizations share certain characteristics in the area of social capital and the level of trust. First of all, multicultural organizations usually have greater cultural capital than monocultural organizations. This results from the pressure on greater openness in multicultural organizations, manifested in:

-

a higher degree of internationalization;

-

greater potential in relation to intercultural communication connected with the knowledge of foreign languages;

-

promotion of internationalization and inclusiveness;

-

a smaller number of stereotypes and prejudices in intercultural contacts.

On the other hand, neither the literature nor the studies conducted as part of our project provided clear-cut evidence that greater concentration of social capital at the organizational level in multicultural enterprises is reflected at the levels of enterprise, competitiveness, or effectiveness of organizational activities. Thus, examining the influence of these correlations on the effectiveness, enterprise, and competitiveness of organizations is a far greater problem. Relationships between social capital and intercultural interactions have been the subject of a number of research projects, however, their results are not so obvious. This issue should be the subject of further research.

References

Adler P, Kwon S (2000) Social capital: the good, the bad and the ugly. In: Alesina E, La Ferrara E (2002) Who trusts others? J Public Econ 85:207–234

Ahn T-K, Ostrom E (2008) Social capital and collective action. In: Castiglione D, Van Deth J, Wolleb G (eds) The handbook of social capital. Oxford University Press, New York, NY

Alesina A, Ferrara E (2000) The determinant of trust. NBER Working paper series, No. 7621

Baker W (2000) Achieving success through social capital. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA

Banfield EC (1953) The moral basis of a backward society. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Banfield EC (1967) The moral basis of a backward society. Free Press, New York, NY, US

Batorski D (2013) Kapitał społeczny i otwartość jako podstawa innowacyjności. https://depot.ceon.pl/handle/123456789/2200

Beard VA (2007) Household contributions to community development in Indonesia. World Dev 35:607–625

Bjørnskov C (2003) The happy few: cross-country evidence on social capital and life satisfaction. Kyklos 56:3–16

Bourdieu P (1986) The forms of capital. In: Richardson J (ed) Handbook of theory and research for sociology of education. Greenwood Press, New York, NY, pp 241–258

Bourdieu P (1990) The logic of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Polity, Cambridge, UK

Burt R (1992) Structural holes versus network closure as social capital. In: Lin N, Cook KS, Burt RS (eds) Social capital: theory and research. Aldine de Gruyter, New York, NY

Burt R (1997) The contingent value of social capital. Adm Sci Q 42(2):339–365

Cassar A, Crowley L, Wydick B (2007) The effect of social capital on group loan repayment: evidence from field experiments. Econ J 117:F85–F106

Christoforou A (2005) On the determinants of social capital in Greece compared to countries of the European Union. FEEM Working paper, No. 68

Cohen D, Prusak L (2001) In good company: how social capital makes organizations work. Harvard Business Press, Cambridge

Coleman JS (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology 1990. Foundations of Social Theory. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Czapiński J (2008) Kapitał ludzki i kapitał społeczny a dobrobyt materialny. Polski paradoks. Zarządzanie Publiczne/Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Krakowie 2(4):5–28

Czapiński J (2011) Miękkie kapitały a dobrobyt materialny—wyzwania dla Polski. In: Czarnota-Bojarska J, Zinserling I (eds) W kręgu psychologii społecznej

Dasgupta P (2000) Economic progress and the ideal of social capital. In: Dasgupta P, Serageldin I (eds) Social capital: a multifaceted perspective. World Bank, Washington, DC

Dasgupta P, Serageldin I (eds) (2001) Social capital: a multifaceted perspective. World Bank, Washington, DC

Doryń W (2010) Wpływ kapitału społecznego na internacjonalizację przedsiębiorstw. Gospodarka Narodowa 11–12:111–125

Deutsch M (1973) The resolution of conflict. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

Durlauf SN, Fafchamps M (2005) Social capital. In: Aghion P, Durlauf S (eds) Handbook of economic growth, 1st edn, vol 1, Chapter 26, Elsevier, pp 1639–1699

Dzwończyk J (2005) Czynniki ograniczające rozwój społeczeństwa obywatelskiego w Polsce po 1989 roku. Zeszyty Naukowe/Akademia Ekonomiczna w Krakowie 692:63–76

Fafchamps M (2006) Development and social capital. J Dev Stud 42:1180–1198

Fukuyama F (1997) Zaufanie. Kapitał społeczny a droga do dobrobytu. Wrocław PWN, Warszawa

Fukuyama F (1999) The great disruption. Profile Books, London, 2002. Social capital and development: The coming agenda SAIS Review 22, pp 23–37

Fukuyama F (2001) Social capital, civil society, and development. Third World Q 22(1):7–20

Giddens A (2003) Stanowienie społeczeństwa. Zysk i S-ka, Poznań

Golinowska S, Boni M (2006) Decentralizacja władzy a funkcje socjalne państwa i rozwiązywanie problemów społecznych

Granovetter M (1985) Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness. Am J Sociol 91:481–510

Grootaert C, Bastelaer T (2002) The role of social capital in development: an empirical assessment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Grudzewski WM, Hejduk IK, Sankowska A, Wańtuchowicz M (2007) Zarządzanie zaufaniem w organizacjach wirtualnych (Trust management in virtual organizations). Difin, Warsaw

Hall M, Dogan E, Zheng B, Mishra A (2001) Trust in physicians and medical institutions. Does it matter? Milbank Q 79(4):613–639

Halman L, Luijkx R (2006) Social capital in contemporary Europe: evidence from the European social survey. Port J Soc Sci 5:65–90

Haley GT, Haley UCV (1999) Weaving opportunities: the influence of overseas Chinese and overseas Indian business networks on Asian business operations. Quorum, Westport, CT, pp 149–170

Hanifan LJ (1916) The rural school community center. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 67:130–8211

Hardin R (1992) The street-level epistemology of trust. Analyse & Kritik 14:152–176

Herbst M (2007) Kapitał ludzki, dochód i wzrost gospodarczy w badaniach empirycznych (Human capital, income and economic growth in empirical studies—in Polish). In: Herbst M (ed) Kapitał ludzki i kapitał społeczny a rozwój regionalny. Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar, Warszawa, pp 98–125

Hitt MA, Lee H, Yucel E (2002) The importance of social capital to the management of multinational enterprise. Asia Pac J Manag 19(2–3):353–372

Jacobs J (1961) The death and life of great American cities. Vintage, New York, NY

Jones IW, Nyland CM, Pollitt MG (2001) How do multinationals build social capital? Evidence from South Africa. ESRC Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge, Cambridge

Johanson J, Vahlne J-E (2009) The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: from liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. J Int Bus Stud 40(9):1411–1431

Kaasa A, Parts E (2008) Individual-level determinants of social capital in Europe. Acta Sociologica 51(2):145–168

Kawachi I et al (1997) Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am J Public Health 87(9):1491–1498

Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Glass R (1999) Social capital and self-rated health: a contextual analysis. Am J Public health 89(8):1187–1193

Knack S, Keefer P (1997) Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q J Econ 112:1251–1288

Kostro K (2005) Kapitał społeczny w teorii ekonomicznej. Gospodarka Narodowa 7–8:1–28

Koufaris M, Kambil A, Labarbera P (2001) Consumer behavior in web-based commerce: an empirical study. Int J Electron Commer 6(2):115–138

Lesser E (2000) Knowledge and social capital. Foundations and applications. Butterworth-Heinemann, Newton, MA

Levi M (1996) Social and unsocial capital: A review essay of Robert Putnam’s making democracy work. Polit Soc 24:46–55

Lin N (2008) A network theory of social capital. In: Castiglione D, Van Deth JW, Wolleb G (eds) The handbook of social capital. Oxford University Press, New York, NY

Łopaciuk-Gonczaryk B (2008) Oddziaływanie kapitału społecznego korporacji na efektywność pracowników. Gospodarka Narodowa 1–2:37–55

Loury GC (1977) A dynamic theory of racial income differences. In: Phyllis A, LaMond WA (eds) Women, minorities, and employment discrimination. D.C. Heath and Company, Lexington Book Division, Lexington, KY

Luhmann N (1988) Familiarity, confidence, trust: problems and alternative. In: Gambetta D (ed) Trust: making and breaking cooperative relations. Blackwell, Oxford

Matysiak A (1999) Źródła kapitału społecznego. Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej we Wrocławiu, Wrocław, s. 60–61

Miguel E, Gertler P, Levine DI (2006) Does industrialization build or destroy social networks? Econ Dev Cult Chang 54:287–317

Miller RA Jr (1974) Are familists amoral? A test of Banfield’s amoral familism hypothesis in a South Italian Village. Am Ethnol 1(3):515–535

Morrow V (1999) Conceptualising social capital in relation to the well‐being of children and young people: a critical review. Sociol Rev 47(4):744–765

Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad Manage Rev 23(2):242–266

Narayan D, Lant P (1999) Cents and sociability: household income and social capital in Rural Tanzania. Econ Dev Cult Chang 47:871–897

Nowak S (1979) System wartości społeczeństwa polskiego. Studia Socjologiczne 4:160

Ostrom E (2001) Social capital: a fad or a fundamental concept? In: Dasgupta P, Serageldin I (eds) Social capital: a multifaceted perspective. World Bank, Washington, DC

Parts E (2003) The dynamics and determinants of social capital in the European Union and neighbouring countries. Interim working paper on the current status of social, Cultural January 2013 and institutional environment in neighbouring countries

Piselli F (2001) Capitale sociale: un concetto situazionale e dinamico. In: Bagnasco A, Piselli F, Pizzorno A, Trigilia C (eds) Il capitale sociale. Istruzioni per l’uso. Il Mulino, Bologna

Putnam RD (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster, New York, NY

Putnam RD (2001) Social capital. Measurement and consequences. Can J Policy Res 2:41–51

Putnam RD, Leonardi R, Nanetti R (1993) Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Putnam RD (1993) The prosperous community: social capital and public life. Am Prospect 13:35–42

Ratajczak Z (1983) Zaufanie interpersonalne. [W:] Gliszczyńska X (red.), Człowiek jako podmiot Ŝycia społecznego. Ossolineum, Wrocław, s 84–104

Reis EP (1998) Banfield’s amoral familism revisited: implications of high inequality structures for civil society, Real civil societies: the dilemmas of institutionalization. Sage, London

Ronald RS (2000) Decay functions. Soc Networks 22(1):1–28

Rose (1999) Getting things done in an anti-modern society: social capital networks in Russia. In: Dasgupta P, Seregeldin I (eds) Social capital: a multifaceted perspective. World Bank, Washington DC

Rothstein B, Stolle D (2002) How political institutions create and destroy social capital: an institutional theory of generalized trust. http://upload.mcgill.ca/politicalscience/011011RothsteinB.pdf. (01.07.2005)

Rothstein B, Stolle D (2003) Social capital, impartiality, and the welfare state: an institutional approach. In: Hooghe M, Stolle D (eds) Generating social capital. Palgrave, New York, NY, pp 141–156

Sabatini F (2006) The empirics of social capital and economic development: a critical perspective. FEEM Working paper 15, Euricse

Sciarrone R (2002) The dark side of social capital: the case of mafia. In: Workshop on social capital and civic involvement. Cornell University

Sen A (2003) Ethical challenges—old and new. In: International Congress on the ethical dimension of development, Brazil, July 3–4

Sierocińska K (2011) Kapitał społeczny. Definiowanie, pomiar i typy. Studia ekonomiczne 1(LXVIII):69

Seifert B, Morris SA, Bartkus BR (2003) Comparing big givers and small givers: financial correlates of corporate philanthropy. J Bus Ethics 54(3):195–211

Silverman SF (1970) Stratification in Italian communities. A regional contrast. In: Plotnicov L, Tunden A (eds), pp 211–299

Sikorski C (2008) O zaletach słabej kultury organizacyjnej. Zarządzanie zasobami ludzkimi 6:65

Sułkowski Ł (2001) Kapitał społeczny a sukces w zarządzaniu przedsiębiorstwem na przykładzie Polski. In: Sukces w zarządzaniu, Problemy organizacyjno-zarządcze i psychospołeczne, Prace Naukowe Akademii Ekonomicznej we Wrocławiu 900

Sułkowski Ł (2003) Znaczenie wartości rodzinnych dla rozwoju przedsiębiorstw. Współczesne Zarządzanie 2:34–43

Sułkowski Ł (2004) Organizacja a rodzina: więzi rodzinne w życiu gospodarczym. Dom Organizatora, Toruń

Sułkowski Ł (2012) Kulturowe procesy zarządzania. Difin, Warszawa

Sułkowski Ł (2013) Syndrom familizmu w polskich organizacjach. In: Firmy Rodzinne –wyzwania globalne i lokalne. Przedsiębiorczość i Zarządzanie XIV/6, part II. Społeczna Akademia Nauk, Łódź

Sztaudynger JJ, Sztaudynger M (2005) Wzrost gospodarczy a kapitał społeczny, prywatyzacja i inflacja. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa

Theiss M (2011) Kapitał społeczny i wykluczenie społeczne. Polityka Społeczna 5–6:43–47

Theiss M (2012) Krewni, znajomi, obywatele: kapitał społeczny a lokalna polityka społeczna. Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, Warszawa

Trutkowski C, Mandes S (2005) Kapitał społeczny w małych miastach, Scholar

Uslaner EM (2002) The moral foundation of trust. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY

Warren MR (2008) The nature and logic of bad social capital. In: Castiglione D, Van Deth J, Wolleb G (eds) The handbook of social capital. Oxford University Press, New York, NY

Whetten DA (2006) Albert and Whetten revisited: strengthening the concept of organizational identity. J Manage Inq 15(3):219–234

Woolcock M, Narayan D (2000) Social capital: implications for development theory, research, and policy. World Bank Res Obs 15:225–249

Wnuk-Lipiński E (1996) Demokratyczna rekonstrukcja. Z socjologii radykalnej zmiany społecznej (Democratic reconstruction. The sociology of radical social change). PWN, Warszawa

Yli-Renko H, Autio E, Sapienza HJ (2001) Social capital, knowledge acquisition, and knowledge exploitation in young technology-based firms. Strateg Manag J 22(6–7):587–613

Zand DE (1972) Trust and managerial problem solving. Adm Sci Q 17:229–239

Zarycki T (2004) Kapitał społeczny a trzy polskie drogi do nowoczesności. Kultura i społeczeństwo 48(2):45–65

Zhou L, Wu WP, Luo X (2007) Internationalization and the performance of Born-Global SMEs: the mediating role of social networks. J Int Bus Stud 38(4):673–690

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges that this chapter is supported by National Science Centre in Poland (research grant no. DEC-2013/09/B/HS4/00498).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sułkowski, Ł. (2017). Social Capital, Trust and Intercultural Interactions. In: Rozkwitalska, M., Sułkowski, Ł., Magala, S. (eds) Intercultural Interactions in the Multicultural Workplace. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39771-9_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39771-9_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-39770-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-39771-9

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)